TWO

Looking Back to Look Forward

The Technology Didn’t Happen Overnight

Thinking futureback includes looking back from the present. Almost nothing happens that is truly new: almost everything was tried and failed years before it succeeded. When thinking about the future, there is limited utility in asking “What’s new?” because if it is truly new it is almost certainly not going to happen anytime soon. It is much more useful to ask “What’s ready to take off?” When COVID-19 hit, many technologies were ready to take off and most of them were not new.

Zoom wasn’t just invented out of nowhere when the COVID-19 shutdown hit.1 “Let’s do a zoom call” became the term that many people used to describe the entire medium of video conferencing. Zoom, FaceTime, Microsoft Teams, WebEx, Skype, GoToMeeting, BlueJeans, and an array of other 2020 brands built on the graves of many failed video conferencing services over a period of more than fifty years. Luckily, desktop video conferencing was well tested and in modest use, so it was ready when it was needed urgently at scale.

At Institute for the Future, we typically think in sixty-year swaths of time: at least ten years ahead and at least fifty years back. While we look to the future for clarity, we look to the past for patterns. A futureback view provides context—the conditions that might allow something to take off.

It is important to take stock of how we got to where we are now regarding offices and officing. This chapter provides our take on the history of offices and officing before the COVID-19 office shutdowns. It provides context for understanding how we got here. Having this context provides a foundation for launching into futureback thinking about offices and officing.

Hierarchical Organizations Want Hierarchical Offices

In 1943, Sir Winston Churchill requested that the House of Commons be rebuilt after the war bombing exactly as it was before its destruction in October 1941. In his speech to the House of Lords, Churchill said, “We shape our buildings; thereafter they shape us.”2 It is important that we are conscious of how our buildings shape us and that we make smart choices. Churchill chose to rebuild buildings like before the war, but now is a time to do something different so our buildings shape us in better ways.

In 1909, Frederick Winslow Taylor published The Principles of Scientific Management.3 In response to the Industrial Revolution, Taylor’s system that he called “scientific management” broke down jobs into basic tasks. Job specialization distributed tasks among workers, each of whom performed one set of actions. Job planning was given to management, along with training and monitoring of employees to be sure they were performing.

In 1920, German sociologist Max Weber built on Taylor’s principles in his seminal work, The Theory of Social and Economic Organizations, which described bureaucracy as the most efficient way of running large organizations.4 Weber agreed with the need for job specialization where jobs were broken down into simple, routine, and well-defined tasks.

Taylorism and bureaucracy are arguably the most significant influences on workplace architecture—in the design of physical offices, in the management of physical offices, and in how work was carried out in physical offices.5

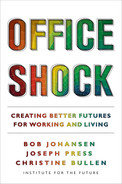

IMAGE 1: Atrium of the Larkin Administration Building. Collection of the Buffalo History Museum. Larkin Company photograph collection, Picture .L37, # 1-35.

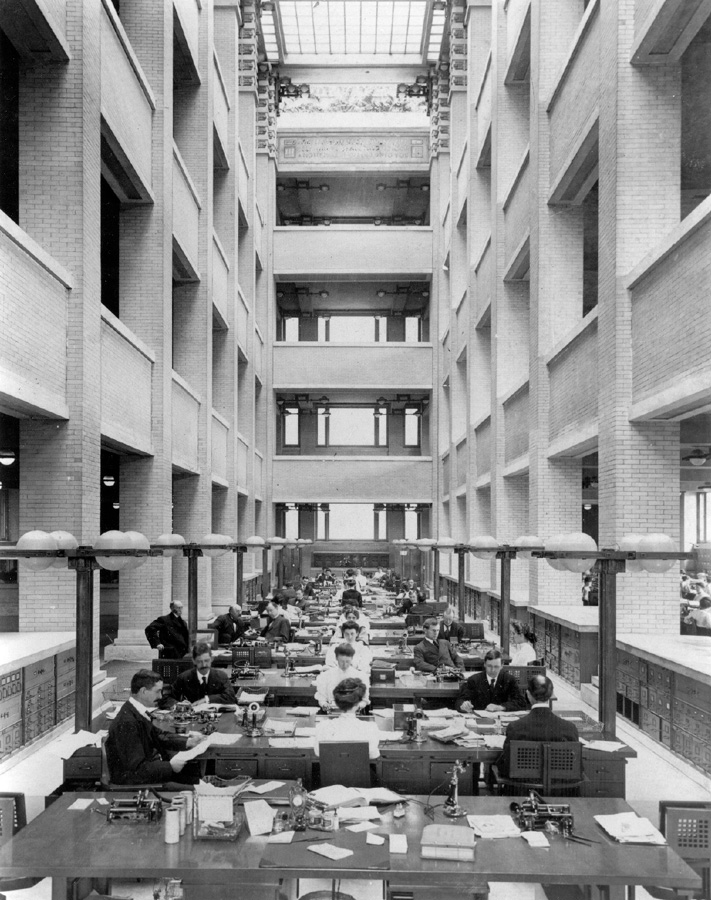

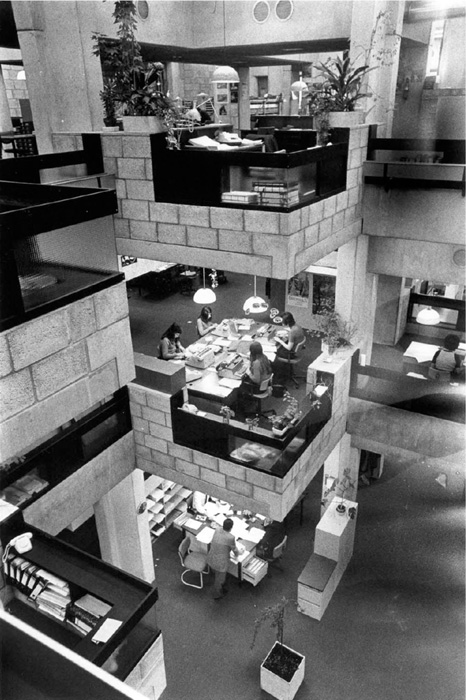

Early office building designs such as Frank Lloyd Wright’s Larkin Building6 (see images 1 and 2) reflected this focus on efficiency, a design trend that continued for decades.

Interior windowless spaces for lower-level employees were surrounded by private offices for managers, often sized and furnished according to the rank of each executive. In addition to displaying a perceived need for supervision of lower-level workers, the space was organized for task specialization. The workflow logically grouped responsibilities to facilitate smooth production, as if the office were a factory.

IMAGE 2: Typing Department in the Larkin Administration Building. Collection of the Buffalo History Museum. Larkin Company photograph collection, Picture .L37, #2-51.

Spurred by the elevator, new construction methods in concrete, and new ways to cool offices, high-rise buildings began to grow. Despite these innovations, the workplace continued to be organized using Taylor’s principles. Hierarchies and ways of working were poured into those concrete office buildings and furniture arrangements.

Unpleasant Offices

Twentieth-century offices evolved little in the period between 1945 and 1970. Most improvements in the 1950s focused on making traditional tasks more efficient using improved manipulation, storage, and retrieval of information stored on paper. The Rolodex, for example, was introduced in 1958 and allowed contact details to be readily at hand on a wheel that twirled through cards that were handwritten or typed individually. It was considered a marvel at the time.

The offices of the past were often awful, at least for lower-level employees. In the 1950s and ’60s, life in the office was characterized in popular media as men and women in formal business attire smoking cigarettes. Women were in the lower-level positions (secretaries and typists), while mostly white men were in managerial positions. There was a significant lack of diversity in all positions except the lowest. The Dolly Parton movie 9 to 5, a comedy grounded in a dreary sexist office, told a realistically creepy story of office life. The popular TV series Mad Men told disturbing stories of office behavior. In a classic film farce of modernity, Playtime, director Jacques Tati brought the unpleasant office to life in a very possible future.

While Playtime, Mad Men, and 9 to 5 were stereotypes, there was a lot of accuracy in how offices of old were portrayed in these films. Office work was organized for command-and-control efficiency. Old-fashioned offices and the executives who ran them were both stodgy and slow to change.

In the 1960s, for example, the IBM Selectric typewriter was viewed as a major innovation, something that was hard to imagine given the long history of the typewriter. Prior to this technology, office communications were typed on a traditional typewriter, which had an unchangeable font and moveable arms for each letter. Fast typists easily jammed the typewriter. The Selectric had a revolving ball with the letters on it, which did not jam and, most importantly, could be switched out to provide a variety of fonts. The people who used to be called “secretaries” were delighted by the variety, but what they were typing and how they worked didn’t change.

Turmoil in the World around Offices

Outside the office, countercultural shocks were everywhere. Major events in the 1960s and ’70s included the Stonewall riots, which many credit with the beginning of the gay rights movement; the first moonwalk on July 20, 1969; a popular music revolution characterized by the Beatles and Woodstock; the resignation of US president Richard Nixon; and the cultural revolution in China. The civil rights movement dates back even further but also had major milestones in the 1960s.

In San Francisco, the first Earth Day was proclaimed in 1970, but little was done to ameliorate the negative effects of human activity on the planet, and no office policies or procedures were changed to lessen its impact. Future Shock became an international bestseller in 1970, an early indication that people recognized that there is volatility in their lives and that it may be harmful.

In 1971, the singer, songwriter, and activist Marvin Gaye asked in song, “What’s Going On?” as a plea for change in the social, economic, environmental, and political turbulence of the times.7 Although these events were shocking to most people, the owners and executives who ran offices were deeply committed to business as usual.

Traditional office buildings were organized for orderliness. They exuded command-and-control efficiency. They were designed so workers could be observed, to ensure they were working hard. Most offices were not designed to encourage trust or develop community. The traditional office was often unproductive and unfair. Many were boxed-in rooms crammed with cubicles and unhappy people.

Technologies for Remote Work Came Slowly

As most offices were focused on efficiency, technological breakthroughs were laying a foundation for potential changes in how work got done. Specifically, the introduction of microcomputers and networks in the 1960s laid the technological foundation for new ways of working and living that didn’t happen until decades later.

Our story of office shock starts in 1945, when Vannevar Bush, the former head of the US Office of Scientific Research and Development, published his vision of the global brain he called “Memex.”8 We think of the Memex as an early vision of the officeverse. Influenced by Bush’s vision, the US Department of Defense began work on the ARPANET, the first distributed network of computers. During the Cold War, the central computers of the day were vulnerable to attack, where distributed processing promised to be more resistant and robust. The ARPANET was the predecessor of the internet.

It is important to note that the ARPANET was a government-seeded innovation that involved many public-private institutions. We will come back to this in chapter 13 on choices for policy makers regarding offices and officing. The distributed ways of working that are common today would have taken much longer to develop if not for government seed money.

While it was initially developed in secret, the ARPANET was introduced to the public in 1972. Bob presented his first professional paper at that conference, which was called the International Conference on Computer Communications. By “communications,” they meant machines communicating with machines. The ARPANET was intended to be a major incremental improvement for data communications for enhanced military security. When people started using that early and very crude internet to communicate with other people, they were chastised for wasting scarce computing power. Using that early internet as a marketplace for buying and selling was unthinkable, until that’s what it became suddenly years afterward. Once those early computers were connected, the mules came to life and started kicking.

In 1972, the National Science Foundation and the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency funded Institute for the Future to think futureback about this unprecedented technology that was unfolding in staggering ways. This first-of-its-kind network had no center, it grew from the edges, and it could not be controlled—though many tried to control it.

Later in Europe, CERN, a high-energy physics research facility, became a major wide-area network hub and is considered the birthplace of the World Wide Web.9

The internet is still evolving in unpredictable ways. The internet and its descendants will always be mules that appear in wildly varied incarnations.

A Mule Disguised as a Mouse

Inventor Douglas C. Engelbart created the first mouse, which looked more like a rat. It provided a new way for ordinary humans—not just computer programmers—to interact with computers easily. The mouse turned out to be a mule.

Engelbart also invented the first windows interface, the first hypermedia capability, the first split-screen video conferencing, and a range of other innovative digital tools that are only now becoming practical. Try searching the web for “The Mother of all Demos” to see the best demo we have ever seen and remember as you watch it that it was done in 1968.

Inspired by Bush’s Memex, Engelbart created the first prototype of a comprehensive integrated office system in Silicon Valley before it was called that. Engelbart’s bold vision was to augment the human intellect, to boost human abilities to collectively deal with complex societal problems. His team at Stanford Research Institute (now SRI International) built and ran the Network Information Center (NIC), the first library on the ARPANET. Engelbart’s integrated office system, initially called NLS (for oNLine System) was marketed unsuccessfully for a short period of time by Tymshare as “Augment.” A quiet, kind, and humble man, Engelbart turned out to be a mule. The world was not ready for him.

When Bob came to the Institute for the Future in 1973, he was the first PhD level social scientist on a team of technologists that was building and testing the new idea of group communication through computer networks. The leader of the team was computer scientist Jacques Vallee, who had just joined IFTF from Engelbart’s lab. Nobody knew what to call the medium they were prototyping on the ARPANET (awkwardly, they called it “computer conferencing”), but today most people would call it social media or collaborative media. The vision and tools for distributed office work were gradually coming to life. For example, since participants in IFTF’s prototype trials were from around the world, the team had wildly varied work hours. When the ARPANET “crashed” (that is, abruptly stopped working—which happened frequently), the ghostly message broadcast to all participants was this: “HOST DEAD,” with no guess about when it might arise from the dead. These early systems were very interesting when they worked, but not ready to scale.

In the early 1970s, the first general purpose microprocessors made their way to offices, without a mouse yet. By the 1980s, the presence of personal computers in the workplace grew rapidly, the global internet was prominent in academic communities, and, in 1989, the World Wide Web was established as the platform for global communication for anyone who wanted to join in. In 1989, Tim Berners-Lee created the World Wide Web, built on the ARPANET infrastructure, which by then had evolved into the internet.

New Tools for Working

Gradually, a series of specialized business tools was introduced into the office. Wang Laboratories invented a word processor in the 1970s that incorporated many of the attributes of today and included a screen (CRT—cathode ray tube—like a television) for viewing and editing the input. Next came specialized software that could be used on a general-purpose microcomputer—essentially a personal computer—like spreadsheet software such as VisiCalc (1979) and Lotus 1-2-3 (1983). This was an important transition in showing that the microcomputer could be used for many different purposes in the office. But the substantial change was in understanding that these general-purpose computers could be linked together through communications software and provide a way for work to be shared and distributed among knowledge workers. A computer on every desk took a long time, followed by a computer in every pocket or purse.

Initially, the communication took place within separate organizations, but with the ARPANET as a model, the opportunity for connecting organizations and people became the goal. People communicating through computers with other people anywhere in the world became possible.

For networks like the internet to expand, there needed to be computers to connect. As with the introduction of the telephone, initially there were very few people who had one and therefore very few people to call. Each computer (or telephone) is a node on a network, and for the network to succeed there must be active nodes. Personal computing emerged as a major innovation when active nodes included computers in organizations and when people took them into their homes. At first, home computers were stand-alone toys for hobbyists, but the communications opportunities and the growth of many kinds of software applications that people enjoyed using catapulted the growth in personal computing.

Although computers could now be personal, and span the globe, understanding how interacting with these new technologies could enhance officing and the workplace was the essential ingredient to change the world of working and living. This was a painfully slow process of fitting new distributed tools into old hierarchal offices.

Telecommuting Was Possible Long before COVID-19

Jack Nilles,10 who coined the term “telecommuting” in the 1970s, was a professor at the University of Southern California studying urban transportation. Recall that the Los Angeles metropolitan area had chosen by this time to de-emphasize its innovative public transportation system in favor of a network of automobile freeways.

Nilles had the vision to see that working remotely was much more possible and desirable than most people thought at the time.11 He was an inspirational part of a global movement, most active in Western Europe, that promoted several novel concepts, including:

![]() Travel/telecommunications Substitution

Travel/telecommunications Substitution

![]() Travel/telecommunications Trade-offs

Travel/telecommunications Trade-offs

![]() Remote Work

Remote Work

In his experiments and research, Jack Nilles proved that telecommuting was viable and desirable, but most companies still weren’t interested. In these early days, many managers expressed their concern that, if they could not see people at their desks, they couldn’t tell if they were really working. Many individual workers liked the idea of telecommuting, but the owners and executives who ran offices were not yet ready to change.

In 1988, Bob wrote a book called Groupware: Computer Support for Business Teams that included seventeen scenarios, only three of which required that people be in person in offices.12 Scenario 17 was focused on nonhuman participants in location-flexible team meetings. Computers were evolving from large central rooms to personal desktops, to distributed networks. Groupware was dedicated to Doug Engelbart and Jacques Vallee.

The notion of augmented group intelligence has been a long time in the making. For example, the Institute for the Future designed and prototyped a collaborative system in 1982 that included nonhuman participants that were computer models.13 Groupware included a scenario called “Nonhuman Participants (Support for Electronic Meetings)” in which the nonhuman advisor on risks associated with various possible investment options was called Coach:

The team meeting for new brokers is just convening. Each trainee has spent the better part of the preceding day working with the Coach, an expert system that has specialized expertise about investment options that the new brokers will be selling in another three weeks. There are many opinions about investment options; even the Coach is only expressing an opinion. The new team discusses the options, consulting again with the Coach at several points during the meeting. The Coach has specialized knowledge that nobody on the team has, but it does not have definitive answers. It is a collaborative process, with all the team members (including the Coach) contributing.14

The Coach was an early prototype for intelligent agents who could augment both individuals and groups. Now, decades later, such things are becoming practical. Once the stuff of science fiction, AI coaches, and companions, are now available.15 In chapter 8, for example, we used a current generation text generator to create a futureback story.

In Groupware, Bob highlighted the innovative work going on at Xerox PARC (Palo Alto Research Center). An innovation hub in the hills of Palo Alto overlooking Stanford University, Xerox PARC led the way with technologies like WYSIWIG (What You See Is What You Get) and GUI (Graphical User Interfaces), which began to make using microprocessor-based computers much easier for any knowledge worker. In addition, Danny Bobrow and Mark Stefik created COLAB to prototype computer support for collaborative work—either in a single location or for distributed teams. Mark Weiser, who later joined IFTF’s board of trustees, invented the term ubiquitous computing: computer support “wherever you go and however you move.” Adele Goldberg and Alan Kay used computers in amazing ways in their work with children and storytelling.

There has always been a strong culture of idea exchange in Silicon Valley. The first time Bob did a presentation at PARC, he was the only social scientist in a room filled with a large group of engineers and computer scientists. Bob was discussing the work of people communicating with people through the ARPANET, and they weren’t buying it since the original purpose of the network was computers communicating with computers. Bob was standing in the room while all of them were slouching on bean bag chairs. Just a few years later, under John Seely Brown, PARC became about half social scientists and half computer scientists. Bill English joined PARC from Engelbart’s lab and PARC brought Engelbart’s core ideas closer to real life. Important PARC innovations made their way into commercial use.

These new insights about how people interacted with computers, and the software to assist knowledge work (for example, word processing and spreadsheets), accelerated the use of personal computing into the 1990s, and by the 2000s social networking (such as Facebook in 2004). This growth continues as more software applications are created that augment knowledge work, provide leisure-time entertainment, and fuel distributed offices and office work of every kind.

Architects Envisioned the Networked Office

As technologies for distributed work were improving gradually, Frank Duffy, workplace architect pioneer and researcher, was among the first to imagine a very different kind of office. Duffy thought that the open and unplanned spaces of office landscaping (inspired by the bürolandschaft from West Germany16) failed to live up to expectations due to noise levels and the excessive interruptions it encouraged. It offended individual concerns for privacy, comfort, environmental control, and personal identity.17

The unresolvable tension between corporate and individual aspirations was a significant problem for bürolandschaft and other open office designs. In the United States, Herman Miller’s “Action Office” provided an alternative: a kit of parts matched to the varied tasks for office work. It addressed the conflicts between privacy and communication inherent to the bürolandschaft schemes.

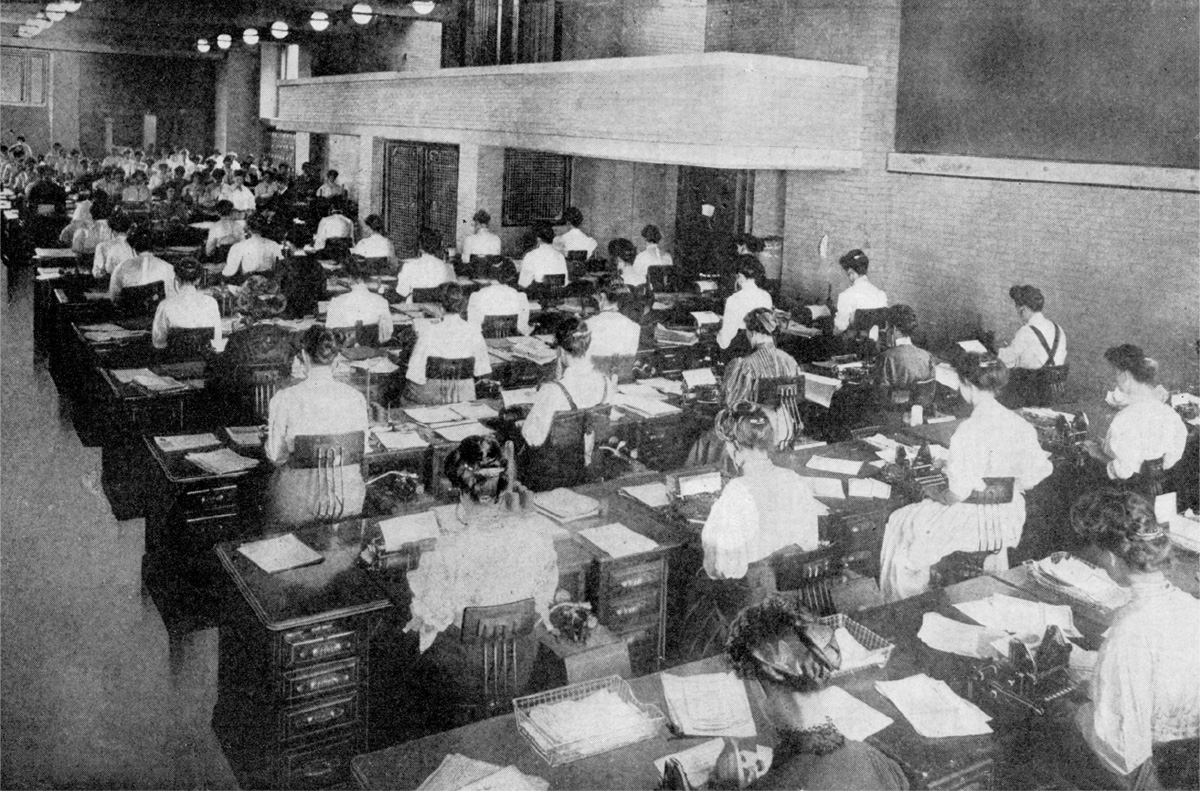

In Europe, the response was quite different. The “Combi” office sought to balance the relationship between individual aspirations and corporate identity by providing space for both. Herman Hertzberger’s the Centraal Beheer Office, illustrated in images 3 and 4, sought to mitigate these tensions by encouraging separate “hives” for varied activities.18

IMAGE 3: Centraal Beheer Office, Axonometric Sketch of Interior Space Plan. Office building Centraal Beheer, Apeldoorn, The Netherlands (1986–1972). Architect Herman Hertzberger.

Flat screens had a major impact on creating hives, according to architect Colin Macgadie:

The widespread introduction of flat screen technology in the late 90s enabled desks to be grouped together in “benches” and freed up valuable space that could now be used to create the café’s, lounge areas, and breakout spaces that helped co-workers and teams feel connected, and began to challenge the thought processes around office design. The Centraal Beheer’s whole concept and architecture encouraged early versions of “Breakout Areas,” but this process was given real impetus and democratized with the physical flexibility the flat screen offered organizations.19

IMAGE 4: Centraal Beheer Office, Interior Photo. Office building Centraal Beheer, Apeldoorn, The Netherlands (1986–1972). Architect Herman Hertzberger. © Willem Diepraam

Spurred on by the revolutionary potential of information technology, Philip Stone and Robert Luchetti claimed that “Your Office Is Where You Are.”20 For the first time the assumption of “one seat per person” in offices was questioned. Reconfiguring the space and time of officing sparked a fundamental rethinking of office design itself.21

Drawing inspiration and insight from the Environmental Behaviorists22 and new information technologies, Francis Duffy wrote in 1997:

Ways of working are changing radically. Information technology sees to that. Based on very new and very different assumptions about the use of time in space, new ways of working are emerging fast. They are inherently more interactive than old office routines and give people far more control over the timing, the content, the tools, and the place of work.23

Resonating with Franklin Becker and Fritz Steel’s perspective on workplaces, Duffy’s design expressed organizational ecology.24 DEGW, Duffy’s architectural practice in which Joseph was working at the time, promoted four types of spaces in offices:

1. The Den | 3. The Hive |

2. The Club | 4. The Cell |

DEGW’s four different workspaces offered “organizations the capacity to both add value through ways of working and to minimize costs.”25 Such innovative rethinking, wrote DEGW’s director of research at the time: “is the major means by which architectural design can provide buildings and workplaces that better support user’s emerging organizational needs.”26

Duffy’s Networked Office allocated space based on work patterns, informed by use. Networked Offices combine the potential of virtuality in the power of in-person experiences. Networked Offices transcend conventional architectural boundaries offering a different kind of relationship between technology and people, and between time and place.

Office shock accelerated Duffy’s spatial dreams into reality, with a new name: the hybrid office. Churchill’s proclamation that our buildings shape us is still true, but now our options for building and communicating are much richer. We don’t have to go back to the way it was.

Impossible Offices Became Mandatory in 2020

The novel coronavirus pandemic of 2020 shoved companies and workers out of their office buildings abruptly. Owners and executives had to open their minds about different ways of working. Alternatives were no longer optional; they were required.

The technology, tools, and visions had been bubbling away in labs and universities for more than half a century, but the concept of “office” was still packed with habits and unexamined assumptions that were not easy to change. Digital tools were gradually coming alive, but there was little demand for change.

At the same time, knowledge workers were more comfortable with using the technology that supported work from anytime/anyplace. Young people or other early users of technology seemed to have an advantage. The rolling risk of pandemics, chronic climate crises, and social injustices shocked everyone. For the first time, many organizations—after being required to work remotely because of COVID-19 shutdowns—began to question the value of traditional offices. Were there other ways to achieve the goals of the organization through creative use of alternative workplaces? Individuals, organizations, and policy makers now can imagine better offices and better ways of officing.

Fortunately, by the time COVID-19 happened, the technology was good enough to use on a large scale. Earlier visionary mules like Engelbart and Nilles had been ignored, but the technology kept improving anyway, and by 2020 when COVID-19 hit, impossible office futures became possible because:

![]() There was an obvious and urgent need to change behaviors regarding where, when, and how work got done. The oil shortage in the late 1970s and the 9/11 terrorist attacks hadn’t been enough to create office shocks that were lasting. COVID-19 was the tipping point that demanded a change that was impossible for years before, but now was mandatory. Indefinite office closures shook everyone, including the people who run offices.

There was an obvious and urgent need to change behaviors regarding where, when, and how work got done. The oil shortage in the late 1970s and the 9/11 terrorist attacks hadn’t been enough to create office shocks that were lasting. COVID-19 was the tipping point that demanded a change that was impossible for years before, but now was mandatory. Indefinite office closures shook everyone, including the people who run offices.

![]() Robust and functional technology made distributed work possible. The early technology for remote work has been in small-scale use since 1968, but it was not easy to use, it was expensive, and it was not dependable until recently. By 2020, the technology, the tools, and the media were at least good enough and they were ready to scale. We expect that the next decade, now that the need is clear, will see dramatic improvements in technology and media for distributed work.

Robust and functional technology made distributed work possible. The early technology for remote work has been in small-scale use since 1968, but it was not easy to use, it was expensive, and it was not dependable until recently. By 2020, the technology, the tools, and the media were at least good enough and they were ready to scale. We expect that the next decade, now that the need is clear, will see dramatic improvements in technology and media for distributed work.

![]() Practical success stories of distributed work spread quickly as the pandemic spread. Until the crisis, visions of distributed work—and the words used to describe these visions—were either not inspirational enough or not practical enough. By the end of 2020, working remotely was the only way to work for millions of people around the world. And some of these new ways of working were very attractive to workers and companies alike.

Practical success stories of distributed work spread quickly as the pandemic spread. Until the crisis, visions of distributed work—and the words used to describe these visions—were either not inspirational enough or not practical enough. By the end of 2020, working remotely was the only way to work for millions of people around the world. And some of these new ways of working were very attractive to workers and companies alike.

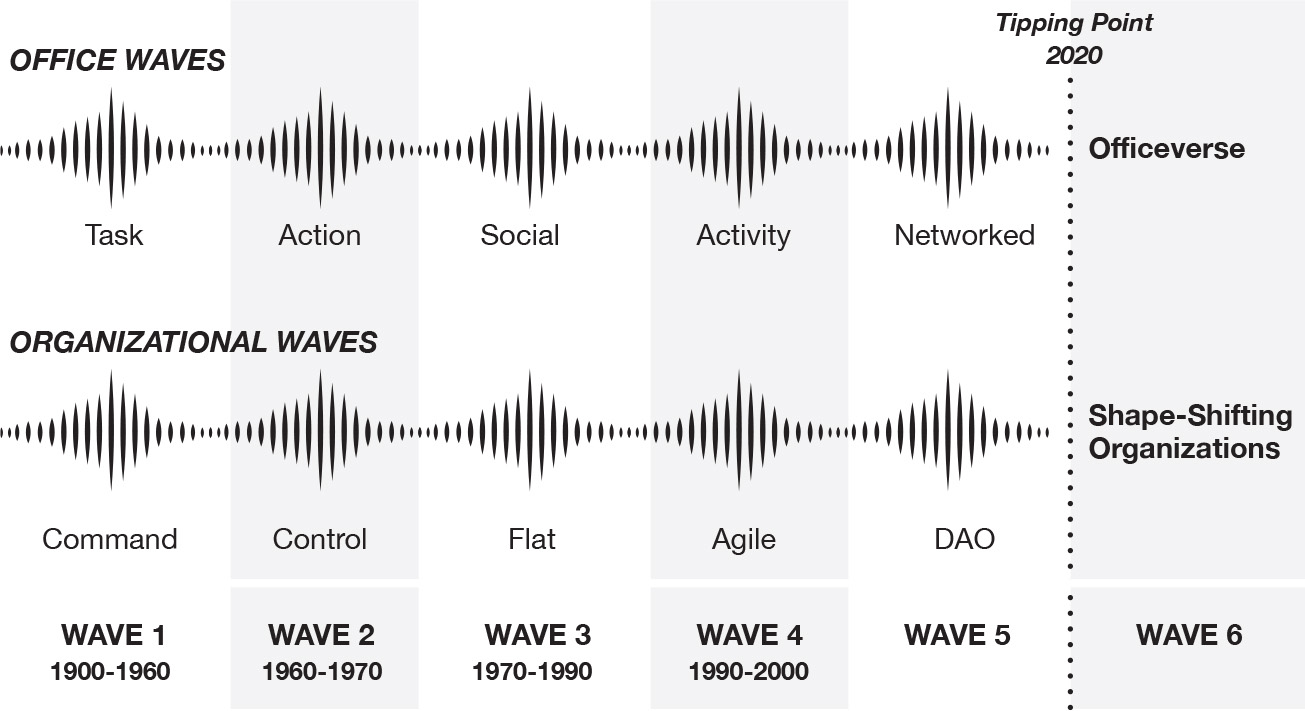

FIGURE 6A: Office and Organizational Waves. Innovations enabling the Great Opportunity of an officeverse and shape-shifting organizations.

Office shock challenged foundational assumptions about where, how, when, and why we work. As office shock becomes a way of life, new fault lines will reveal opportunities for new ways of working and living. Office shock hit hard in 2020, but the aftershocks will roll on into the future for at least a decade or beyond.

Looking futureback, we see a convergence of three drivers of change—technology (internet waves), places (office waves), and people (organizational waves)—that underlie what we’re calling the Great Opportunity for deep change in offices and officing. Figure 6a illustrates the timeline of evolution in where we work and the ways we organize ourselves to work.

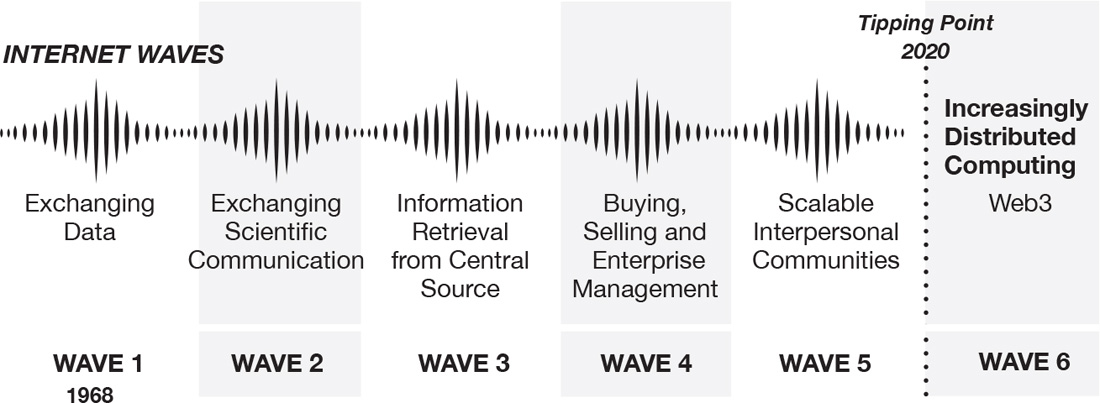

FIGURE 6B: Internet Waves. Innovations enabling the Great Opportunity of increasingly distributed computing.

COVID-19 sparked new ways of using internet connectivity in ways that had never been attempted at massive scale. As illustrated in figure 6b, the internet was already the connective tissue for offices and distributed work, but suddenly the stakes went up dramatically. Both COVID-19 and the internet are mules—unpredictable wild cards that cannot be controlled.

Triggered by COVID-19, the waves of office, organization, and technology changes cascaded into unprecedented tipping points changing where, when, and how we work. The year 2020 was when so many mules converged, sparking office shock and a great opportunity to do offices and officing a lot better than what had been done in the past.

With increasingly distributed computing, shape-shifting organizations, and happier workers, after nearly a decade the officeverse is now a great possibility because the directions of change are clear:

From | Toward |

Hierarchical and Centralized | Networked and Distributed |

Standalone and Individual | Connected and Cross-Organizational |

Fixed Offices | Shape-Shifting Ways of Working |

Specialized Jobs | Augmented Generalists |

By thinking futureback—forecasting futures, provoking insight, and aligning actions—individuals, organizations, and policy makers can now reimagine where and how office work can and should be done in the future.

Your Choices as You Look Back to Look Forward

Everyone has a choice of whether to learn from history or risk remaking old mistakes. It took more than fifty years for distributed digital technologies to be an overnight success in 2020. Zooming wasn’t just created anew when COVID-19 hit. In this chapter we shared our stories of this evolution and what it implies about what’s next as the officeverse emerges.

As you think about your own personal story and reflect on technologies for distributed work over the last fifty years, consider these questions:

1. The networked office broke resistance to change in hierarchical offices. The year 2020 was a tipping point for change. How can you use futureback thinking to imagine better ways of working for yourself and your organization from now going forward?

2. The birth of augmented knowledge work began to grow slowly in the 1970s, and we are still asking the question of how we best combine what humans do with what machines can do. What is your stance regarding augmented intelligence (more on this coming in chapter 8)? What are the aspects of work where you need the most augmentation? What areas do you want to keep to yourself?

3. Technology has evolved dramatically in the past fifty years, making impossible things possible. In this chapter, we’ve shared our stories about this evolution. What are the lessons you take from this history?

4. The past is riddled with present-forward thinking about technology that limits imagination. How might you encourage more futureback thinking?