CHAPTER 11

El Círculo: Inclusiveness Across Generations

THE LATINO BIENVENIDO SPIRIT is reflected in the way the culture embraces the circle of life, from the promise of youth to the wisdom of age. Unlike societies in which people retire, Latinos honor their elders, who continue contributing. As a silver-haired octogenarian, when I am asked if I am going to retire, I assert, “No, no! I am just getting started. You ain’t seen nothing yet!” I plan to follow in the footsteps of the social justice trail blazer activist Dolores Huerta, who is going strong in her nineties!

Just as mis padres sacrificed so their children could have a better life, Latinos have an unshakeable commitment to educating, supporting, and including younger generations. We know they are el futuro; coming generations will actualize Latino power and potential. Since Latino leaders understood that it would take many centuries to advance, preparing subsequent generations has been an age-old practice.

This approach is even more urgent ahora! Youth is a defining characteristic of the Latino community—nearly 6 in 10 are millennials or younger. One-third are under eighteen.1 Never before has an ethnic group made up so large a share of the youngest Americans. By sheer force of numbers alone, young Latinos will shape the twenty-first century.

This youthful vitality, however, is not just a Latino phenomenon. We are experiencing immense demographic shifts! In the general population, millennials and Gen Zs are the most numerous in history. Projections show that by 2036 they will make up more than half of all eligible voters.2 At the same time, ten thousand baby boomers retire every day. Advancing the next generations to take the helm of leadership is one of the pressing challenges of our times.

Moreover, young people today face an uncertain future. To address this, many identify as change makers. Change makers utilize an activist form of leadership that aims to uproot systemic oppression. Young people lead with an intersectional, multicultural approach that includes a nonbinary identity and global connectivity. Wired to the internet and social media, they define themselves as digital activists utilizing technology and the media to promote social change and engage millions of people.

Young Latino leaders are on the front lines of social-change activism and are addressing unique issues such as cultural identity, immigration, and continued discrimination. For instance, 35 percent of Latino millennials are immigrants, and fully one-quarter of those under eighteen have at least one unauthorized immigrant parent.3 These immigrant roots make young Latinos more global and give them a fierce determination to change US policies on immigration.

This chapter puts forth an intergenerational leadership model based on the strategies and practices young Latinos are using today. The young leaders included in this chapter are stoking up the Sí se puede tradition established by generations before them. First, let’s look at intergenerational leadership and how this approach requires restructuring relationships across different ages into more equitable and respectful practices.

Intergenerational Leadership

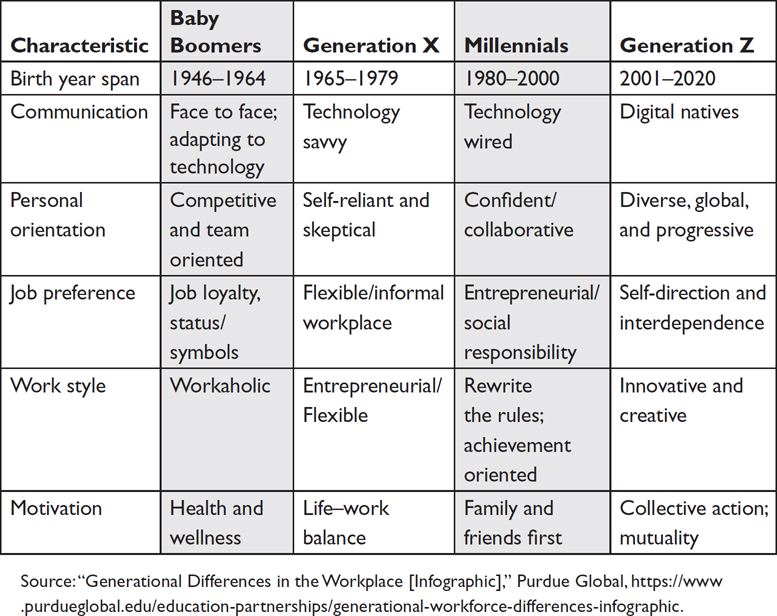

INTERGENERATIONAL LEADERSHIP IS SHARING responsibility with people of different ages and integrating into the leadership process the vision, priorities, and methods utilized by distinct generations. A generation is a group of people born within a certain time period whose shared age and life experiences shape a distinct worldview with particular characteristics, preferences, and values.

The concept of “generations,” generally accepted today, is a recent invention based on expanding life expectancy, which results in multiple generations existing in the same historical time frame. The first official generation designated by the US census was the baby boomers, those born from 1946 to 1964.4

Crafting an intergenerational leadership model requires understanding the key political, economic, and social factors that shape each generation. In this chapter we zero in on millennials and Generation Z, who make up 42 percent of the US population. When you add in our youngest generation, that number jumps to 51 percent!5 A more in-depth view of generational differences is included at the end of this chapter.

Traditional leadership implied a hierarchy in which established and usually older leaders handed down knowledge and doled out rewards. In contrast, intergenerational leadership is based on the principle of the leader as equal, which fosters collaborative relationships and develops each person’s capacity.

Equitable relationships cultivate a deep sense of We and foster mutual respect and partnerships. Intergenerational leadership invites the unique wisdom and strength of every generation to come together to create a more viable and equitable future.

Latinos are an intergenerational community. Social occasions, fundraisers, political rallies, community events, and family gatherings will include a mélange of ages, from abuelas to niños (children). Young Latinos were raised in traditionally We cultures, so that intergenerational collaboration resonates with their upbringing and worldview. Moreover, Latinos come from large extended families comprising multiple generations and have a tradition of living and working with many ages. (In my familia, for example, my sister Rosemary was twenty years older than me and helped buy the family casa where I grew up.) Today, 27 percent of young Latinos live in households that are multigenerational, and 14 percent live in three-generational households.6

Building an intergenerational leadership force is essential when a group’s advancement depends on people power, collaboration, and collective resources. Intergenerational leadership strengthens community capacity, ensures continuity, and builds leadership by the many—the critical mass needed for social change. Hilda Solis notes the Latino intergenerational spirit: “We have to motivate our young people to build upon our legacies. We have to encourage them to reach out and include other people. We need to make sure there is a pathway to follow, and that leadership is passed down generation to generation.”

Latinos will transform the future together—each generation supporting the others and tapping into the unique gifts different ages bring. Jamie Margolin underscores this tendency: “Our movements must be intergenerational. . . . We, the youth, are standing on the shoulders of the change makers before us, and we must always acknowledge and respect that.”

An Uncertain Future: Igniting Youth Activism

WHILE WE CANNOT REVIEW all the myriad issues affecting young people’s lives, we will explore five that are crippling their futures: college debt, housing insecurity, climate change, job or income challenges, and life-span threats. These impact all young people but have a greater effect on Latinos because they also must address continued discrimination and lower economic status.

In the past twenty years, the average tuition at private universities jumped 124 percent while in-state tuition at public universities increased by a whopping 179 percent. This means graduating from college leaves students with an average debt of $28,950.7 How can young people envision their future when they are saddled with crippling debt even before they begin their adult lives?

Young people are getting shut out of the housing market, especially in urban areas. Seventy percent cannot afford to buy a casa.8 Nearly a third are rent burdened, meaning 30 percent or more of their income goes to rent.9 In 2020 (abetted by the COVID-19 epidemic), 52 percent of all young adults returned home, becoming the first generation since the Great Depression to “have to” live with their parents. For young Latinos (eighteen to twenty-nine years old), this number was 58 percent.10

In their short lifetimes, millennials and Zs have witnessed one ecological disaster after another—raging forest fires, catastrophic flooding, horrendous hurricanes, and suffocating summers. Climate change is a source of anxiety for 59 percent of young people.11 This jumped to 83 percent of Gen Z, leading to a term, eco-anxiety, related to fears about the future of the environment.12

Millennials have less wealth than earlier generations, despite having the highest workforce participation and education. Baby boomers controlled 21 percent of the nation’s wealth when they were around the same age as millennials today—that’s over four times as much as millennials own now.13 Millennials are also burdened with wage stagnation and job insecurity—a staggering 1 in 4 jobs is currently at risk of being automated.14 Additionally, growing income disparity is even more dire for Latinos. According to the US Federal Reserve, in 2019 White households owned 85.5 percent of the nation’s wealth, Black households owned 4.2 percent, and Hispanics owned 3.1 percent.15

Finally, millennials are the first generation to have a shorter life span than their parents. One out of two is predicted to get cancer.16 Since 2017, gun violence is now the leading cause of injury-related deaths among children and young adults.17 These issues are fueling young people’s activism, urging them to work for a better future—the one they will inherit. In doing so, they follow the tradition of activists who came before them and fought for social change.

César Chávez was only thirty-four when he started advocating for farm workers’ rights. A few years later he cofounded the National Farm Workers Association, which later became United Farm Workers.18 At twenty-eight years old, Martin Luther King Jr. formed the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, which fought to end segregation and to achieve civil rights. In the 1960s, young college students across the nation marched to end the war in Vietnam. In 1963, during the Children’s Crusade, a march in Birmingham, Alabama, thousands of youth ages six to sixteen were arrested at a peaceful rally, resulting in national outrage and a civil rights victory.19

I began my activist journey at nineteen, when I demonstrated to end segregation at the University of Florida. During my senior year, two African American students were admitted. At twenty-six I joined early feminists demanding equal rights for women. And at thirty-five I was a founder and then executive director of Denver’s Mi Casa Resource Center for women.

Likewise, today, Indigenous youth ignited the movement at the Standing Rock Sioux reservation to protect their water and block the Dakota Pipeline. Black Lives Matter—the international movement to stop state-sanctioned violence against Black people—was founded by three young women activists, Patrisse Cullors, Alicia Garza, and Opal Tometi.20 Undocumented young Latinos pushing for immigrant rights launched United We Dream (UWD). Even though they risked being deported or otherwise separated from their families for taking part in demonstrations, they describe themselves as fearless youth fighting to improve the lives of themselves, their families, and their communities.21

Traditionally, young people have been the forerunners carrying the torch for equality and justice! Margolin explains, “Youth leadership is transformational and visionary. Youth must lead because they have always shifted culture towards progress and collective liberation.”

Promoting a Cultural Shift—Transforming Social Identity

YES! YOUNG LATINO LEADERS are igniting a new activism. Through technology, they engage larger numbers of people, augmenting leadership by the many. They identify as multicultural and global, accept a whole spectrum of gender identities, and champion LGBTQ rights. Young Latinos today are transforming our social identity.

We are using the term social identity here not in the personal sense but in the way a majority might define themselves—something like “national character.” Historically, America’s social identity centered around a White, Anglo-Saxon, Protestant ethic that defined man’s nature as competitive, acquisitive, and individualistic.22 It also touted White superiority and dominance. The aftermath is a segregated and racist society based on exclusion, conformity, and homogeneity.

Latinos and other young people today are rejecting these tendencies and welcoming an inclusive, diverse, and universal concept of our common humanity. They are constructing a new social identity, which is being championed by the following practices: being multicultural and global, acknowledging gender fluidity and LGBTQ normalcy, sharing personal narratives, and cultivating allies and partners.

A Multicultural and Global Identity

The Black Lives Matter movement brought front and center the urgency for racial reckoning and healing. A new desire to dismantle structural racism, injustice, and inequities exists today. Now is the time to focus resources and energy to heal old wounds, repair the past, and acknowledge the pain and suffering White supremacy has left in its wake.

Yet these conversations and actions are really the fodder for older generations. Most young people are on the other side of this and instead are celebrating their multicultural, mixed, and expansive diversity. Diversity defines them! Half of millennials and Gen Z come from communities of color, and Latinos make up 27 percent of millennials and 35 percent of Gen Z.23

Additionally, as we have noted, according to the 2020 census the multicultural population increased 276 percent in the previous decade. The “White and Some Other Race” population grew more than 1,000 percent.24 This phenomenal identity shift gives Latino and other young leaders the people power to lead the transformation to a diverse multicultural society.

This generation has also grown up with a global mind-set; they communicate and connect across the globe every day! Since half the people in the world are currently under thirty, a new international youth culture is emerging.25 If you look at young people in the United States, in many parts of South America, in Europe, and even in China, you’ll notice they dress in a similar fashion (casual, layered, and gray/blue/brown colors; sneakers and boots). They listen to world music that has an Indigenous and fusion flair; watch the same shows, news, and movies; and use Facebook and WhatsApp to build community. They spark international social movements. This has been birthed by a global consumer culture that markets music, technology, clothes, and food products worldwide, along with technological access and travel.

Moreover, many Latinos have ancient kinship ties to people from twenty-six countries and have immigrant roots which nurture an international identity. Twenty-two percent of Gen Zs and 14 percent of millennials have at least one immigrant parent, bringing the world right to the family dinner table.26

These factors have also sparked youth-led international social-change movements and have made younger generations more favorably disposed to working with groups, leaders, and countries beyond their border. For instance, millennials are at least 10 percentage points more in favor of the United Nations than are Gen Xers or boomers.27 And as we will see, young people understand that issues such as climate change affect us all, especially the generations that will follow.

Young Latino immigrants and migrants are especially keyed into the global impact of many issues that threaten their future. One of United We Dream’s guiding principles states, “UWD recognizes that the root causes of migration include imperialism, colonization, violence, persecution, natural disasters, and capitalism and economic globalization that impose poverty and displacement—too often due to policy decisions being made in other countries. To reach true justice, we must push back against global policies that force people to move. We are part of the international community and will stand with all people seeking a better life, peace, and safety.”28 Because of their numbers and their multiracial and multiethnic heritage, young Latinos are lynchpins for fastening together broad, diverse, intergenerational, and international coalitions.

Championing Gender Equity and LGBTQ Rights

As my Gen Z grandson Ishmael explained to me, “Most people in my generation (or at least almost everyone that I know) see gender and sexuality not as something set in stone but as a spectrum.” From transgender to cisgender (a person whose sense of identity and gender correspond with their birth sex), there is gender fluidity. This is apparent in the listing of pronouns (He/She/They/Ze) after a person’s name and has become so accepted that Merriam-Webster chose the singular they for a person with a nonbinary gender as its word of the year in 2019.29 The growing acceptance of LGBTQ+ rights is one of the great social transformations of our times.

Decades ago, I was talking with my good friend José, who was steadying himself to come out of the closet to his familia. He was nervous and yet hopeful, and I comforted him: “We would never stop loving our children! Familia primera y siempre [first and always]!” And that is exactly what is happening. As a people-centered culture with a bienvenido spirit, Latinos are wired to accept differences, including the spectrum of gender identity. Excluding people from the comunidad or familia would be a cultural anathema. (Although in every group there remain religious, conservative, and homophobic factions that are not supportive.)

This has now been validated by the GenForward Survey, which found that Latino millennials were more likely than other ethnicity groups to self-identify as LGBTQ or nonstraight. Twenty-two percent identify as LGBTQ, compared to 14 percent of African Americans, 13 percent of Whites, and 9 percent of Asian Americans.30 Jamie Margolin, for instance, dedicated her book, Youth to Power, “To the queer kids. We are unstoppable.” LGBTQ Latinos are shaping political movements.

Cristina Jimenez agrees. “When we look at United We Dream, most of the people have been women or queer. In the context of immigrant youth organizing, LGBTQ+ are front and center in shaping this movement.”

And when gay Latinos are on the “inside,” they break new ground! Ritchie Torres is the first openly gay Afro-Latino in the US Congress and was the first gay representative on the New York City Council. As a member of the council, he helped to open the first homeless shelter for LGBTQ youth and secured funds for senior centers to serve LGBTQ people.

Torres speaks about his decision to come out publicly about being gay: “It was a question of integrity. I’m asking residents who have been failed by their elected officials to trust me. How can I be trusted if I’m telling lies about something as basic as my sexual identity? Coming out has taught me an ethic of radical authenticity. Not only am I open about my sexuality, but I’m also open about every aspect of my life. . . . My experience as an LGBTQ person has made me far more authentic as an elected official than I otherwise would be.”31

Young Latinos also serve as allies for the LGBTQ community. Congressman Ruben Gallego is proud of his support. “When I was in the military, I was involved with Voices of Honor [a nationwide effort to repeal the military’s ‘Don’t ask, don’t tell’ policy]. I’ve always been supportive of the LGBTQ community and am a member of LGBTQ Equality Caucus in Congress. Having a male, a Latino veteran, does help change people’s minds, especially about gender equality. I’m a cultural translator for some Latino men who are still carrying a lot of homophobic feelings.”

Being Authentic and Real: Share Your Story

Latinos come from a culture of storytelling grounded in the oral tradition. Storytelling weaves connections and strengthens community—so vital to We, people-oriented cultures. In part II, “Preparing to Lead,” we studied personalismo—the importance of the leader’s character and how sharing one’s own background builds cultural rapport with people. Young Latinos have broadened this to include personal stories, which engenders a deeper level of trust, unity, and community.

Jimenez emphasizes how vital this was for undocumented youth: “Storytelling played a big role in our work because that allowed people in an organic way to build connections. Young people are seeking to be seen and to belong.” Jimenez sees sharing stories as a strategy: “We need to create a sense of belonging and pride that systematically, because of colonization, our people haven’t had—to be proud of who we are and where we come from. This can erase feeling that we don’t belong or should be whitewashed versus celebrating the multiethnic, multireligious, multiracial richness of our diverse community.”

Moreover, the passion and promise a person brings to leadership is often rooted in the narratives of their early lives. Torres’s childhood birthed his activism: “I was raised by a single mother who kept our family afloat on a $4.25 minimum wage. I grew up in a housing project full of leaks and lead, with no reliable heat or hot water in the winter. As a product of public housing, public schools, and public hospitals, I had a dream of fighting for my community in the hopes of building a better Bronx.”

Likewise, Gallego points to his childhood as a training ground for becoming a leader. “I didn’t grow up in the best of circumstances. My mom and dad are immigrants. I have three sisters. My father left when I was young. I became a leader first by being a leader in my family, helping my mom raise my three sisters.”

Sharing stories is also a useful tactic to create unity among Latino subgroups. Jimenez realized, “Despite being from different parts of the Latin American diaspora, the belonging comes because of language, music, food, because of the similar stories around how our parents raised us, but also similar stories of migration.”

Becoming Allies and Partners

Many young people recognize that relationships based on hierarchy and dominance perpetuate inequality. They are seeking instead respect, engagement, mutuality, and partnership. In the past, more experienced, well-positioned people often guided younger ones through mentoring—the mentor taught the behaviors, attitudes, language, rules, and norms that fostered success. They opened doors and networks so their protégés would be accepted by those with access or power. In a society structured around racial inequity and White privilege, however, mentoring implied a hierarchy and an approach in which established, usually older, White male leaders handed down knowledge and bestowed influence. Mentoring was integral to succession planning so that power, wealth, and privilege were retained and passed on to select people. Mentoring groomed White leaders and those in their favor, which perpetuated hierarchy, inequity, racism, and White privilege—the very dynamics young leaders oppose.

Instead, today young people are seeking allies, which signifies a relationship with people of many ages based on mutual respect and learning. An ally infers a partnership—a lateral relationship with someone who stands side by side, watches your back, and supports you. Ally is also used in social change work to describe someone who is not a member of an underrepresented group but who utilizes their position of power and credibility to challenge inequality and support inclusion.

Allies reach across generations, listen, and are open to new ways of working together. Young people inspire and offer a vision for the future. Older leaders serve as cultural ambassadors, provide historical perspectives, and make connections. Julián Castro speaks to this: “People from different generations need to work together. This way, we can preserve our history, keep the integrity of those who have more experience and a long-term perspective. Young people will understand the sacrifices made in the past. Otherwise, young people may compromise and lose their culture. Only by staying connected across generations can we keep moving forward together.”

Cooperation between generations requires older leaders to shake off the belief that they know best or they should be in charge, and it requires young people to develop patience and to learn from those who have come before. Antonia Pantoja, who started ASPIRA, which has now trained seven generations of Puerto Rican youth, had a knack for building circular relationships and encouraging young people to take responsibility. “What do you do about the future?” she asked. “I make the future. You make the future. We make the future together.”

Latino leadership is like a relay race where one generation passes the torch to the next—and then the next and the next. Ensuring every generation has a seat at the leadership table supports continuity and ongoing progress.

This Is How You Do It! The Circle of Latina Leadership Program

THE CIRCLE OF LATINA Leadership in Denver was an inter-generational leadership initiative that brought together Latinas ranging from age ninety to their early teens. Twenty years later, the young women who completed the program are mature leaders and the voice for Latina empowerment in metro Denver.

In the early 2000s, I invited a group of seasoned Latina leaders to talk about the future of our community. We realized that the mutual support, networking, and the coaching we had received from more established leaders and from each other were foundational to what we had accomplished, and we wanted to play that forward.

Thus was born the Circle of Latina Leadership, a yearlong intergenerational program for emerging leaders in their twenties and thirties. The word ally had not surfaced yet, but the Circle brought together four generations to support each other and to advance Latina progress.

More established leaders guided program participants, connected them with their cultural identity, and assisted them in charting their careers and community contributions. One founder, Lena Archuleta, the first Hispanic principal in the Denver Public Schools, shared her wisdom and experience with Circle women until she passed away at ninety. Lena and a small group of community madrinas (honorary godmothers) stood as reminders of their lifelong commitment to advancing the Latino community. Participants in turn adopted junior high school girls as hermanitas (little sisters), helping them with self-esteem, school success, and cultural identity.

Over 165 emerging leaders completed the program and today run nonprofit organizations, serve on boards of directors, direct government agencies, and advocate for critical issues such as education, women’s empowerment, climate change, and reproductive rights. A new generation of Latina leaders has taken the helm!

Strategies for Social Justice

YOUNG LATINOS SIMPLY HAVE a vision for a new world that is multicultural and global and welcomes the wide spectrum of gender identity. Now we look at four leadership strategies that they bring to social-change work: being change makers, understanding intersectionality and systemic oppression, leveraging an insider-outsider approach, and utilizing technology to multiply impact.

The Change Makers

Watch out, because in the last ten minutes, while you were reading this chapter, twenty young Latinos turned eighteen, and they have the critical mass to influence and transform society.32 To accomplish this, many are assuming the role of change makers—a term utilized by young people who push for large-scale social change and see themselves as capable of creating this. Change makers are described as a force for social evolution who, through innovative thinking, gathering resources, and determination, make change happen.

UWD cofounder Cristina Jimenez realized, “I began to see that young people had the power to influence change and the responsibility to fight for our community. We knew the language. We understood how to navigate different systems. We had access to social media. We also had the courage that young people have and the urgency to act, regardless of the consequences.”

Young Latino leaders, due to higher education, comfort with technology, and a global perspective, understand that promoting social justice is a lifetime work. Torres clearly states, “I am on a mission to fight racially concentrated poverty and to be a national champion for the urban poor!”

Jimenez concurs. “What’s clear is the work that I do is a lifelong commitment. Regardless of a particular role or title, organization or project or campaign, I want to be a vessel for empowering people, particularly communities of color and Latinos. To let the next folks in. And to make sure that we can live freely, thrive, and have a life with dignity.”

In Youth to Power, Margolin, the climate activist, claims that young people should be “disrupting the status quo, making your voice heard, challenging problematic authority, changing the culture, changing laws, and yes changing the world.”33 And young people are stepping up: 32 percent of Gen Z and 28 percent of millennials took at least one of four actions (donating money, contacting an elected official, volunteering, or attending a rally) to help address climate change in 2021, compared with 23 percent of Gen X and 21 percent of baby boomers and older adults.34

Congressman Gallego, who at forty-two is a spring chicken (considering that the average age of House members is fifty-eight and of senators is sixty-four), urges young people to be bold. “If you’re a young leader, at least in politics, you’re going to have to break the rules in order for you to lead. And some of that means going against old political structures that do not want to let you in. So being strong and aggressive and taking initiative helps you.” Similarly, Congressman Torres states, “Members of my generation, the millennials, and Generation Z have a strong ethic of social justice.” Following the activist tradition of young Latinos, the first Gen Z elected to Congress in 2022 is Maxwell Alejandro Frost, an Afro-Latino. He has experienced firsthand the impact of poverty, gun violence, and climate change and campaigned on the promise, “I’ve dedicated my life to fighting for justice.”

Margolin also sees young people as having “fresh energy, insight, and a unique power to create change in our world. The voices of young people are so powerful because we have the moral high ground. We didn’t create any of the systems of oppression that hold us and our world down.”35

Understanding Intersectionality and Systemic Oppression

They stood outside the US Capitol on a cold, wintry day, thousands of miles from the warm climates their families had come from. Despite fear of deportation and being called “aliens,” undocumented, and even criminals, the young immigrants stood firm. “Together, we fight for education, economic, racial, gender, reproductive, and environmental justice. We fight to build power within our communities, justice, and dignity for all—regardless of immigration status.” This is the rallying cry for United We Dream, the largest immigrant youth–led organization in the United States.

Many undocumented Latino immigrants are on the front lines of social justice work. They know personally how immigration and the growing number of refugees are part of systemic oppression with long, gnarled roots. The UWD mission states, “We believe in leading with a multi-ethnic, intersectional path. Climate change, sexism, gender discrimination, racism, colonialism, economic disparity, gun violence, and unbridled capitalism are interconnected.”36

While the immigrant crisis impacts people crossing national borders, climate change affects everyone on the planet, regardless of borders. Young Latino leaders understand that climate change and immigration are intersectional issues. Margolin explains, “Systems of oppression (capitalism, colonialism, racism, and patriarchy) have led to climate change; therefore, we must shift our culture away from these systems. Intersectional movement building is the only way we can achieve collective liberation . . . and unify communities who wish to join our struggle for a safe and healthy future.”37

In past times, people worked on social justice issues in a silo fashion—movements were segmented. This piecemeal approach limited impact and scope. Young Latino activists today understand the systemic origins of injustice and inequality. Torres speaks to this: “Young people increasingly defined racism as institutional rather than in individual terms. Not simply as the intent of an individual but the impact of institutional arrangements on vulnerable communities such as the Latino community. So it’s certainly true that Latinos increasingly view inequality through a systemic lens.”

Leveraging an Insider-Outsider Approach

Young Latino change makers utilize voting and the political process, but they also make use of movement- and cause-oriented strategies. Their tactics reflect an insider-outsider approach. Congressman Torres is a stellar example of promoting issues from inside the halls of the US Congress: “If you are on a mission to fight racially concentrated poverty . . . then you have to be a policy maker on the national stage.”

Yet he champions putting pressure on the system. “What distinguishes young Latino leaders is the willingness to play the outside game, to agitate publicly to be creative disruptors of the status quo. I think that has become an essential element of leadership in our present political moment, because we’ve seen the limitations of the inside game. We’ve seen that it doesn’t work well anymore.”

An impressive example of utilizing an insider-outsider strategy was the 2012 executive order by President Obama establishing Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals—an emotional victory for undocumented young Latinos. DACA meant they would not be deported, could go to college, and could legally get a job. To secure DACA, thousands of undocumented youths rose up, told their stories, and made their plight a cause célèbre that garnered support across the country.38

UWD used multiple strategies. Jimenez recounts, “Obama campaigned on being very progressive, and promises to push for immigration reform and the Dream Act. Then he gets into office—and, granted, it’s an economic downturn, a total crisis—but he chooses to make health care his priority and not work on immigration. So we rally for Congress to work on immigration reform. Clearly the votes are not there for legislation. When this happens, we regroup and restrategize. People from Latino, civil rights, Black organizations were saying, ‘Don’t push Obama. He is our friend. Go and push Congress.’ But we said, ‘We already did that!’”

Jimenez continues:

We talk to creative legal minds and immigration experts, who advise us to pressure Obama to take an administrative action and to stop deportations. That is when we went against some civil rights leaders and more conventional or older activists. We launched our campaign that included a National Day of Action, with rallies, marches, and protest across the nation. We mobilized thousands of youths, used social media to tell our stories, brought together allies such as labor leaders and the faith sectors. Ultimately, this led to the victory of DACA in 2012—the first major immigration policy in over 25 years!

Torres notes how young activists are redefining an old tradition: “Every movement requires moderates and radicals. An insider like President Lyndon Johnson needed an outsider like Dr. Martin Luther King. And a moderate like Dr. King needed a radical like Malcolm X. And it’s the creative tension between the insider and the outsider game, the creative tension between moderates and radicals, that creates the conditions for social transformation.”

He continues, “I am an insider, but I need activists on the outside to create space for me to move the ball forward as much as I can on the inside. And that gives me leverage. The outside game can expand the realm of what is politically possible on the inside. I think an older generation might view it as a nuisance. The younger elected officials celebrate the value of the outside game. Because you wouldn’t be sitting in that seat if it wasn’t for the outside game.”

Using Technology to Multiply Impact

OK, young Latinos, run to your computers and look up “mimeograph machines.” In the early sixties, this was a coveted tool of community organizers. We would crank it up and print flyers. Then we would post them on bulletin boards, speak at meetings, and go door to door spreading the good news. Making Xerox copies replaced this, but all and all, community organizing was a labor-intensive, on-your-feet process. Technology, especially the internet, social media, and cell phones, has revolutionized social change and movement politics.

Torres explains, “The tools are different. We’re living in a time when you’re one hashtag away from sparking a social movement on Twitter: #Me too, #I can’t breathe, #Black Lives Matter. Millennials and Gen Z are masters at harnessing the power of social media to elevate political causes. Demonstrations that would have taken years to organize can now emerge spontaneously overnight.”

Margolin met the three cofounders with whom she planned the national day of mass action, to protest inaction on climate change, on the internet. In less than a year, they virtually organized twenty-five sister cities, from Los Angeles to New York and internationally. The Washington, DC, marchers met with lawmakers to push for the Green New Deal. These actions led to founding Zero Hour, which advocates for climate justice and has partner chapters around the world, including in Australia, Brazil, Colombia, India, and Spain. Utilizing technology, these activists are uniting support for youth-led climate activism globally.

Stephanie Valencia describes herself as a “digital strategist” and is “at the nexus of politics, technology, and leadership.” She is a founder of EquisLabs, a virtual organization that tracks online information on Latinos and holds social media platforms accountable on Latino content.39 The aim is to provide digital and communications support to Latino organizations to massively increase civic participation and power. While Latino leaders have worked on this for generations, the use of technology to grow “Latino media ecosystems” can explode the influence of the growing Latino demographics.

As a long-term community organizer, I am in awe of the larger scope and impact that young Latinos are having through the internet and social media. Jimenez underscores this: “Our generation ‘lives’ the internet and has access to a much larger number of people. With UWD, for example, we were touching about 5 million people every month. There is a much larger number of people aware of what is happening.”

Young Latinos Leadership

Young Latinos are infusing their community with new vision, energy, and drive. They are revitalizing Latino activism and bringing it into a modern context. As Congressman Maxwell Frost advised the Democratic Party, “I think our party shouldn’t be afraid of talking about bold, transformational change, things that maybe we won’t get tomorrow. It’s what we’re fighting for. It’s the world we (young people) believe in.”40