6

Laying Out Your Plan

In this chapter, you learn the guiding principle of project managers, all about plotting your course, initiating a work breakdown structure, and the difference between action and results (deliverables).

No Surprises

For other than self-initiated projects, it is tempting to believe that the most important aspect of a project is to achieve the desired outcome on time and on budget. As vital as that is, something else is even more important. As you initiate, engage in, and proceed with your project, you want to ensure that you don’t surprise the authorizing party or any other individuals who have a stake in the outcome of your project.

Keeping others informed along the way, as necessary, is your prime responsibility. When you keep stakeholders “in the information loop,” you keep anxiety levels to a minimum. If others receive regular progress reports on your project, and receive bad news early rather than late, then they don’t have to be constantly checking up on you. Indeed, many won’t be overly concerned. And, if the changes needed do surface, you still have time to incorporate them.

Stakeholders, as previously cited, are those people who maintain a vested interest in having a project succeed, and those who will be impacted by the project or its outcomes. Thus, they could also include the authorizing party, top management, department and division heads, other project managers and project management teams, clients, and constituents, as well as parties external to an organization.

The more you keep others in the loop, the higher your credibility will be as a project manager. By reporting to others on a regular basis, you also keep yourself and the project in check. After all, if you’re making progress according to plan, then keeping others informed is a relatively cheerful process. And, having to keep them informed is a safeguard against you allowing the project to meander.

What do the stakeholders want to know? They want to know the project status, whether you are on schedule, costs to date, and the overall project outlook in regards to achieving the desired outcome. They want to know the likelihood that project costs might exceed the budget, the chances that the schedule might go off course, any anticipated problems, and most importantly, any impediments that might loom or that could threaten the project team’s ability to achieve the desired outcome.

You don’t need to issue reports constantly, such as on the hour, or even daily in some cases. Based on the nature and length of the project, the interests of the various stakeholders, and your desired outcome, reporting daily, every few days, weekly, or even biweekly might be best. (See Chapter 13, “Reporting Results,” for more on communications and reporting.)

For a project lasting only a couple of weeks, daily status reports might be appropriate. For projects of three months or more, weekly is probably wise. For a longer-term project running a half year or more, biweekly or semimonthly reports might be appropriate. In any case, the wise project manager safeguards against stakeholders being surprised.

A Plan, Good or Bad

A good plan, to emphasize, indicates everything you can determine, up to the present moment, that needs to be addressed to accomplish the desired project outcome. A good plan provides clarity and direction. It helps you to determine if you are where you need to be, and if not, what it will take to arrive there.

Good or bad, any plan is better than no plan (see Chapter 3, “So, You’re Going to Manage a Project?”). With a bad plan, at least you have the potential to upgrade and improve it. But with no plan, you are like a boat adrift at sea, with no compass, no GPS, and clouds covering the whole night sky so you can’t even navigate by the stars.

From Nothing to Something

Perhaps you were lucky. The authorizing party might have given you an outline, notes, or a chart of some sort, as a starting point for you to lay out your plan. Maybe some kind of feasibility study, corporate memo, or internal report served as the forerunner to your project plan, delineating needs and opportunities of the organization that now represent clues as to what you need to perform on your project.

Often, though, no such preliminary documents are available. You receive your marching orders from an eight-minute conference with your boss, or via e-mail, or over the phone. When you query your boss for some documentation, he or she offers a couple of pages from a file folder. Whatever the origin of your project, you have to start somewhere.

Many project managers find value in starting with the end in mind, even if many of the details of getting there are only sketchy. As such, they consider these kinds of questions:

◾ What is the desired final outcome?

◾ When does it need to be achieved?

◾ What is the total budget?

From there, consider what is the scope, how wide need you cast the net, and how deep is your sea? By starting with major known elements of the project, you begin to fill in your plan, in reverse (see Chapter 5, “What Do You Want to Accomplish?”), leading back to this actual day. We’ll cover the use of software in Chapter 11, “Choosing Project Management Software,” and Chapter 12, “A Sampling of Popular Programs.” For now, we’ll proceed as if pen and paper, or a simple spreadsheet, is all you have. Later, you can transfer the process to your most suitable format.

A Journey of 1,000 Miles

In establishing your plan, as project manager your key challenge is to ascertain the relationship of different tasks or events to one another, and then to coordinate them so that the project is executed in a cost-effective and efficient manner. In laying out your plan, you could end up with 10 steps, 50, or 150 or more.

Some people call each step a task, while some prefer to use the term event, because not each step represents a pure task. Sometimes a step merely represents something that has to happen. Subordinate activities to the events or tasks are subtasks. There can be numerous subtasks to each task or event.

The primary planning tools in plotting your path, as briefly introduced in Chapter 2, “Industry Norms—Should You Conform?,” are the work breakdown structure (WBS), the Gantt chart, and the critical path method (CPM), all of which represent a schedule network. A path is a chronological sequence of tasks, each dependent on predecessors. The critical path is the longest complete path of a project. This balance of this chapter focuses on the work breakdown structure. I’ll address the other tools in Chapter 9, “Gantt Charts,” and Chapter 10, “Critical Path Method.”

A work breakdown structure consists of a complete depiction of the tasks necessary to achieve successful project completion. Project plans, which highlight the tasks that need to be accomplished to successfully complete a project, are vital, from which scheduling, delegating, and budgeting are derived.

You and Me against the World?

Maybe you’re alone and staring at a blank page, or perhaps your boss is helping you. Possibly an assistant project manager or someone who will be on the project management team is helping you lay out your plan. If someone is working with you, or if you have someone who can give you regular feedback, that is to your extreme benefit. Not receiving regular feedback is risky!

Depending on the duration and complexity of your project, it is difficult to lay out a comprehensive plan that takes into account all aspects of the project, every critical event, associated subtasks, and the coordination of everything. To emphasize: If you can acquire any help in plotting your path, take it!

In laying out your plan, consider the big picture of what you want to accomplish, and then, to the best of your ability, divide up the project into phases. By chunking out the project into phases, you have a better chance of not missing anything. How many phases? That depends on the project, but usually it is between two and five.

With help or without it, here is a succinct way to proceed with your plan: List all jobs that need to be accomplished to attain the desired outcome. For each job, list a series of tasks in logical sequences to accomplish it. For each task, estimate a duration, resources required to perform it, and cost of materials. Use the total duration of the job, times the human resources required to determine the cost. Note: All such information can be consolidated by using a planning program.

The Work Breakdown Structure (WBS)

The WBS has become synonymous with a task list. Observe that the term “work breakdown” structure has the accidental double meaning of “breaking down” (as in no longer working, and bringing progress to a halt). However, use of this traditional term prevails and, as employed here, it refers to a positive, preferred tool for effectively managing projects.

The basic activities involved in completing the WBS are as follows:

◾ Identify the events or task and subtasks associated with them. They are paramount to achieving the desired objective.

◾ Plot them, using an outline, tree diagram, or combination thereof to determine dependencies or an efficient sequence.

◾ Estimate the level of effort required, usually in terms of person-days, and start and stop times for each task and subtask.

◾ Identify supporting resources and when they can be available, how long they are at your service, and when and how they must be returned.

◾ Establish a budget for the entire project, for phases if applicable, and perhaps for specific events or tasks.

◾ Assign target dates for the completion of events or tasks.

◾ Establish a roster of deliverables, many of which are presented in accordance with achieving milestones.

◾ Obtain approval of your plan from the authorizing party—the last item in Figure 2.

In Many Forms

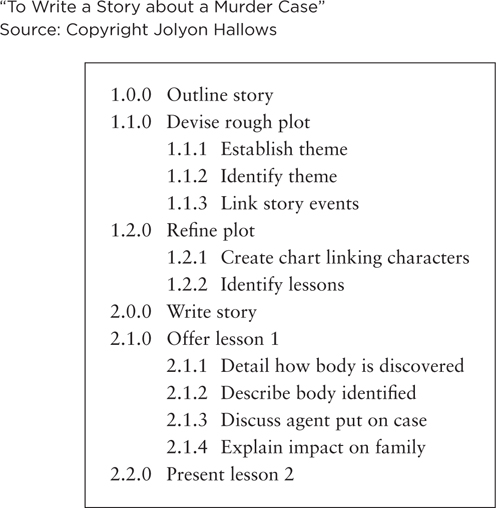

The simplest form of WBS is the outline, although it can also appear as a tree diagram or other chart. Think of the WBS as your initial planning tool for meeting the project objective(s) on the way to that final, singular, sweet triumph.

Sticking with the outline, the WBS lists each task, each associated subtask, each milestone, and each deliverable. The WBS can be used to plot assignments and schedules as well as to maintain focus on the budget. Figure 2 shows a simple example of such an outline.

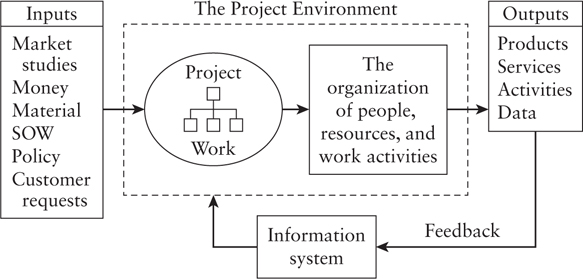

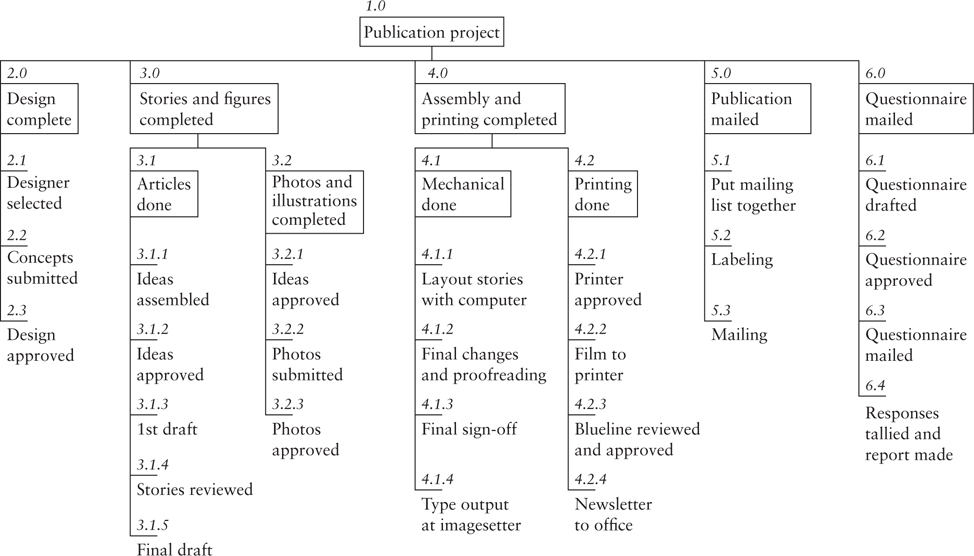

A Project Environment chart, such as that in Figure 3, is particularly useful when your project has a lot of layers, such as when many subtasks contribute to the overall accomplishment of a task, which in turn contributes to the completion of a phase, which leads to another phase, which ultimately leads to project completion.

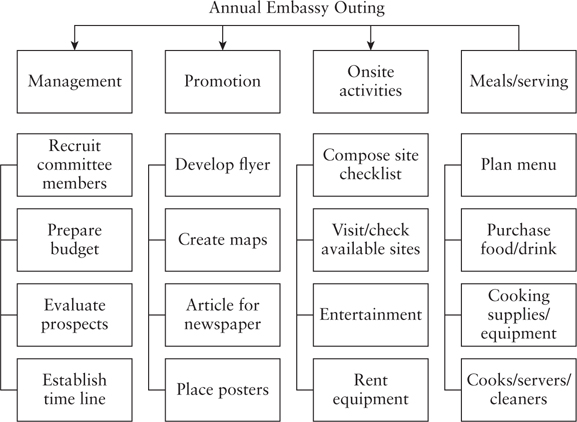

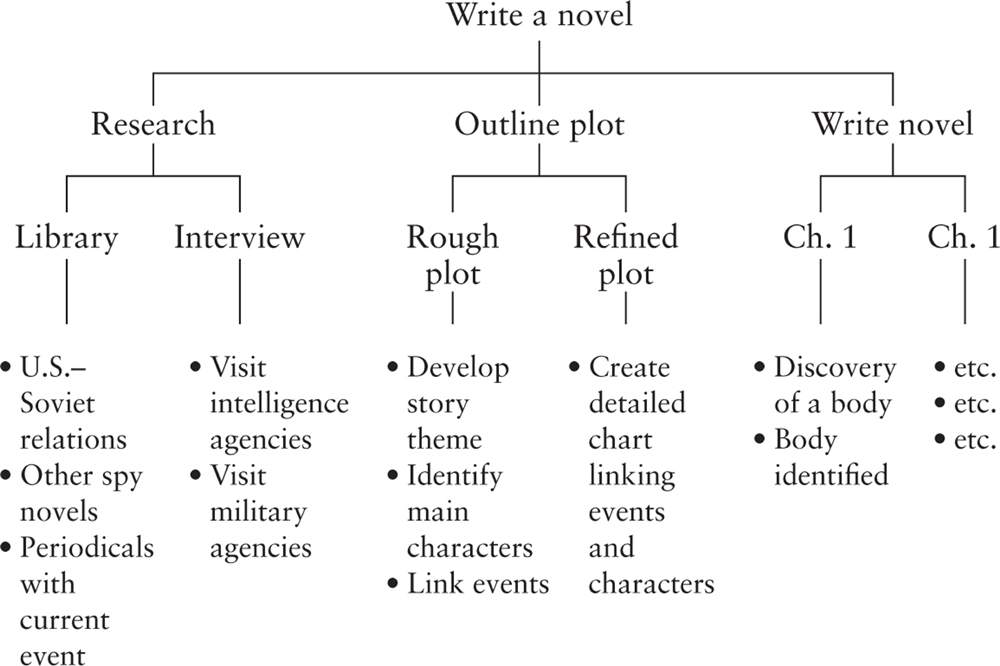

A Tree Diagram, such as the one shown in Figure 4, represents a high-level summary of the key elements of a work breakdown structure (WBS). A full WBS, by contrast, presents tasks, duration, description of tasks, beginning and ending dates, staff responsibilities, and the budgeted amount.

FIGURE 3 The Project Environment

Maintaining a Project Outline

The WBS allows you the opportunity to break tasks into individual components. This gives you a firm grasp of what needs to be done even at the lowest of levels. Hence, the WBS aids in scheduling, doling out, and even budgeting for assignments.

Details, Details

How many levels of tasks and subtasks should you have? It depends on the project’s complexity. While scads of details could seem overwhelming, if your work breakdown structure is well organized, you will have positioned yourself to handle even challenging projects, such as hosting next year’s international convention, finding a new type of fuel injection system, or coordinating a statewide volunteer effort.

By heaping on the level of detail, you increase the chances that you’ll handle all or most aspects of the project. The potential risk of having too many subtasks is that you might become bogged down in details and overly focused on tasks, not outcomes! Fortunately, as you proceed in execution, you find that some of the subtasks (and sub-subtasks) are taken care of as a result of some other action.

Some project managers contend that there is no such thing as “too many” subtasks. You plan the work that you know has to be done. The people who do the work rely on these lists of tasks and subtasks. While the level of detail is up to you, as a general rule the smallest of sub-tasks to be listed in the WBS would be synonymous with the smallest unit that you as the project manager need to manage. For example, ensuring that some needed supplies were on hand at the appropriate time could well make your list.

Generally, it is better to have listed more details than fewer. If you haven’t plotted all that you can foresee, then once the project commences, you might be beset by burdensome challenges because you understated the work that needs to be performed. Or, you might experience unnecessary delays because someone didn’t recognize the importance of having some crucial item on hand.

Team-Generated Subtasks?

Could your project management team devise their own sub-work breakdown structures to pinpoint their individual responsibilities and, thus, have a greater level of detail than your WBS? Actually, yes. Ideally, you empower your staff to effectively execute delegated responsibilities. Within those assignments, considerable leeway often exists as to how the assignments are performed best. The net result, often, is that a WBS established in collaboration is a far more accurate tool.

Your forward-thinking project team members might naturally gravitate toward their own mini-WBS. Often, good team members devise subtask routines that exceed what you actually need to preside over as project manager—unless the procedure happens to be worth repeating with other project team members or on other projects in the future.

The Functional WBS

In the example shown in Figure 5, the WBS is divided into separate functions. This method of plotting the WBS is particularly effective for project managers presiding over team members who could also be divided based on functional lines. In this case, the WBS gives a quick and accurate snapshot of how the project is divided up and which teams are responsible for what.

FIGURE 5 Combination Tree Diagram and Outline WBS

FIGURE 6 Segment of an Outline and Tree Outline WBS

As you can observe, each form of WBS, outline, and tree diagram offers different benefits and has different shortcomings. For example, the outline is more effective at conveying minute levels of detail toward the achievement of specific tasks. When many subteams exist within an overall project team, and each one has specific responsibilities, an outline can be unwieldy, because it doesn’t visually separate activities according to functional lines.

The tree diagram WBS shown in Figure 6 visually separates functional activities. Its major shortcoming is that to convey high levels of task detail, the tree diagram would be huge. All the tasks and subtasks of all the players, in all the functional departments, would necessitate constructing a large and complex chart.

Such a chart is actually a hybrid of the detailed outline and the tree diagram. Nevertheless, for various reasons many project managers resort to this technique. By constructing both an outline and a tree outline WBS, and then combining the two, however large and unwieldy the combination becomes, you end up with a single document that illustrates the totality of the entire project.

More Complexity, More Help

With this potential level of detail for your project, it is vital to obtain help when first laying out your plan. Even relatively small projects of short duration could require accomplishing a variety of tasks and subtasks.

Eventually, each subtask requires an estimate of labor hours: How long will it take for somebody to complete it, and what will it cost? (See Chapter 7, “Assembling Your Plan.”) You will have to determine how many staff hours, staff days, staff weeks, and so on, will be needed, based on the plan that you’ve laid out. From there, you could run into issues concerning which individuals you’ll be able to recruit, how many hours your staff members will be available, and the project costs per hour or per day.

Preparing your WBS also provides you with a preview of which project resources might be required beyond human resources. These could include computer equipment, other tools, office or plant space and facilities, and so on.

If your plotted tasks and subtasks reveal that project staff will be traveling in pursuit of the desired outcome, then auto and airfare costs, room and board, and other associated travel expenses need to be considered. If certain portions of the project will be farmed out to subcontractors or non-project staff, associated costs will accrue as well.

What Should We Deliver?

Completing project milestones, often associated with the completion of a project deliverable, is an indicator that you are on target for completing the project successfully. Deliverables can take a wide variety of forms. Many deliverables are actually related to project reporting. These could include, but are not limited to

◾ A list of deliverables. One of your deliverables could be a compendium of all other deliverables!

◾ The desired end product or service as a result of the project.

◾ A quality assurance plan. If your team is empowered to design something that requires exact specifications—perhaps some new engineering procedure, product, or service offering—how will you ensure requisite levels of quality?

◾ A schedule. Schedules can be deliverables, particularly when your project has multiple phases and you are only in the first phase or the preliminary part of the first phase. It then becomes understood that as you delve into the project, you will gain a fuller understanding of what can be delivered and when. Hence the schedule itself can become a much-anticipated deliverable.

◾ The overall budget, estimates, your work plan, cost benefit analysis, and other documentation can all be deliverables, also. A cost benefit analysis is a determination of whether to proceed based on the monetary amounts, time, and resources required for the proposed solution versus the desirability of the outcome or outcomes.

Another type of deliverable centers on acquisition and procurement. A government agency or a large contractor could empower a project manager and the project management team to develop requests for proposals (RFPs), invitations to bid, or requests for estimates as project deliverables. Once the proposals or bids come in, proposal evaluation procedures have to be in place. The following are examples:

◾ Software evaluation plans

◾ Maintenance plans

◾ Hardware and equipment evaluation plans

◾ Assessment tools

The wide variety of other deliverables might include

◾ Business guidelines

◾ Lexicon or dictionary

◾ Buy-versus-make analysis

◾ A phase-out plan

◾ Training procedures

◾ Product prototype

◾ Implementation plans

◾ Reporting forms

◾ Application

◾ Product specifications

◾ Close-out procedures

◾ Software code

◾ Experimental design

◾ Test results

◾ Process models

It’s Results That Count

In preparing the WBS and associated deliverables, you need to focus on results and not on activities. The plan that you initiate and further develop becomes the operating manual for the project team.

One project manager on a new software project requested that team-member programmers develop a certain number of lines of code per day in one phase of a project. She felt that this would be a useful indicator of the level of productivity of her individual project team members.

In their efforts to be productive members of the project team, the programmers developed many new lines of code each day. The result, however, was riddled with errors and insufficient for completing that phase of the project. It put the overall project way behind schedule and behind budget.

Rather than making task and subtask assignments related to the number of lines of new code developed, the tasks and subtasks should have reflected code that accomplished a specific, observable capability that led to the project goal. Then, project programmers would have concentrated on code efficiency and viability, as opposed to volume. Often, it’s quality, not quantity, that counts.

Supporting Tools

When laying out your plan, you’re bound to experience many starts and stops, redirections, and second thoughts. If you have a white board, on which you can simply write down your current thoughts and have them stored to disc and printed later, then you already know that form of documentation is valuable.

Many people simply use stick-em pads, often as large as three by five inches. An event or task can be confined to one stick-em note, with associated subtasks on that same note or an attached note. These can then be moved around at will, either on paper or on a white board, as you are plotting out your plan.

Stick-em pads certainly can be used in combination with a white board. Simply stick them in place (or the best place you can determine at the moment). If you don’t have a white board, you can also use a copying machine or scanner to take a snapshot of your current thinking.

To further ease your burden, you can use colors. These could include different colored stick-em notes, colored dots, magic markers, flares, and highlighters. Each event or task could be a different color, or like subtasks could be a uniform color. The options are unlimited and are basically your choice.

Many project managers find it useful and convenient to use colors to track the responsibilities of individual project team members. For example, everything that Scott is responsible for will be in orange and everything Monica works on will be green.

Some project managers find it convenient to number tasks and subtasks. Keep it simple, however, when numbering tasks or subtasks. You don’t want to end up with outline structures such as 1-1.2.34, where your task sequence might be more confusing than not having them numbered at all.

Bounce Your Plan off Others

After you’ve laid out what you feel is a comprehensive plan that will accomplish the mission, bounce it off others—even those who for one reason or another were not available to participate in it. You don’t want to fall so in love with your WBS that you can’t accept the input of others, or worse, don’t even see the flaws. Remember, the more involved your project is, the easier it is to miss something!

◾ You want people to give it a critical eye.

◾ You want to have them play devil’s advocate.

◾ You want them to challenge you.

◾ You want them to question you as to why you went left instead of right.

Maybe they quickly see something that you flat-out missed. Perhaps they can suggest a way to combine several subtasks into one. Possibly they can point out where you’ve been using ill-matched metrics or the wrong skill level. Or they can identify where you lack buy-in checkpoints with stakeholders.

◾ ◾ ◾

In the next chapter, we add flesh and bones to your WBS, and focus on assigning staff, establishing time frames, and setting a budget.

QUICK RECAP

◾ Regardless of how worthy your project and how brilliant your plan are, keeping others informed along the way, as necessary, is your prime directive.

◾ Carefully scoping out the project and laying out an effective project plan minimizes the potential for surprises, reveals what needs to be done, provides clarity, and offers direction.

◾ The WBS (work breakdown structure) is a primary planning tool in plotting your path.

◾ The WBS lists each task, each associated subtask, milestones, and deliverables, and also can be used to plot assignments and schedules and to maintain focus on the budget.

◾ You don’t want to fall so in love with your WBS that you can’t accept the input of others, possibly leading you to miss major flaws.