CHAPTER FOUR

Implementing a Core Team Process

There is no such thing as an accident. What we call by that name is the effect of some cause which we do not see.

VOLTAIRE, LETTRES DE MEMMIUS III

Successful projects are completed by project teams, not upper managers. But the background work of upper management teams often leads to project team success. Good project teams may seem to come together by accident. The right people may happen to coalesce on a team, but usually good project teams result from upper managers’ setting the stage that allows team success. This chapter reviews the benefits of developing and supporting a core team system for project management. Project teams represent the cornerstone of the postbureaucratic organization. They confer benefits but also have costs. In particular, upper management flexibility is affected when core teams are in place; upper managers often sense that some of their power is lost to the teams. Upper management teams need to agree that the benefits are worth the costs and support team implementation. Otherwise, the benefits discussed in this chapter will not accrue.

The Concept of Core Teams

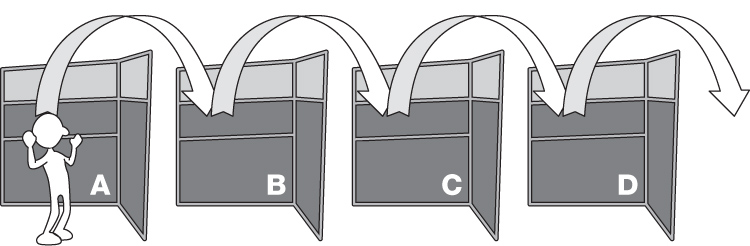

Most organizations are segmented into departments that help achieve economies of scale when producing repeat products. However, the department structure is not the best one for producing new products or applications. Developing a new product involves passing it through all departments until it is ready for market. Along the way, it will undoubtedly encounter the over-the-wall problem (see Figure 4.1), where it is passed back and forth between two departments and often back to a previous department. This causes delay and adds to project cycle time, and the transit times and numerous handoffs cause information loss that decreases final product quality. The over-the-wall method is not good project management.

One way to eliminate this problem is to establish a core team for each project composed of a person from each affected department. These individuals work on the project from beginning to end. The core team members represent their departments and direct the work of the people in that department on the project. They are empowered to make decisions about the project. Others may come and go on the project as needed, but the core team is the stable group of people who are continuously dedicated to the project (see Figure 4.2).

An example of using core teams to decrease cycle time and focus on customer expectations is the Ingersoll-Rand case (Kleinfield, 1990). Reviewing its cycle time for new tool development, the company found “it was taking three years to make a tool, then three and a half, and heading towards four” (p. 1). It described its development process as a series of walls:

FIGURE 4.1 The Over-the-Wall Problem

FIGURE 4.2 Core Teams Save Time

Marketing would think up a product and throw it over the wall separating it from engineering. Engineering would look at what came flying over and say “Did some lunatic dream this up?” and whip it back to marketing. Later it would thunder back in revised form. Engineering would then work up a design and toss it over the wall to manufacturing, but back it would go. Later manufacturing would make the product and hurl it over the wall to sales. These people would try to sell it to customers who perhaps did not want it in the first place. (Kleinfield, 1990, p. 1)

Ingersoll-Rand responded by developing a core team of six people that was dedicated to the project. This team cut the design cycle to a year and a half. Attesting to the quality the team was able to produce, the new tool won an award from the Industrial Design Society of America. The project team formation was such a radical departure from standard procedures that it would not have been possible without upper management support for the core team process.

A core team is typically made up of representatives from each department involved in developing and implementing the new product or application. To receive maximum benefit from a core team, assign members to work on the project full time. Time division diminishes the ability to focus attention on any one project. The learning process necessary on projects requires long periods of concentrated effort in order to arrive at creative solutions. Such effort is impossible if people are spread among several projects that all require the same long concentration, and without concentrated effort, the quality of a final product invariably suffers.

To get highest quality in minimum time, projects need full-time core team members— preferably all in one location. Collocated team members can most easily and frequently exchange ideas; many difficult team communication problems are eliminated or reduced when team members interact on a daily basis. When team members from different departments see each other every day, they also begin to lose some of their departmental identity and begin to identify more with the team. This fosters team cohesiveness while continuing the benefits of a multidisciplinary perspective. Collocation is thus an important impetus to the process of project team building.

For some projects, it may not be feasible to have all team members working full time for the entire duration of the project. Projects typically require different expertise at different phases, so some members may move on and off the team. But while these temporary members are working on the project, they should do so full time. Core team members, however, do not move in and out and should therefore be full time on the project from beginning to end.

When Allen-Bradley adopted this approach, it specified that cross-tunctional teams would see product development through from “womb-to-tomb” (Heckscher and Donnellon, 1994, p. 225). By staying with the project throughout its lifetime, the core team members are aware of or involved in all major decisions made about the product, and they “own” the product as a team. Each core team member should feel accountability for the whole project, not just one piece of it, and this can be accomplished only when they stay for the duration. Promoting such team ownership is an important aspect of the upper manager’s role in creating the environment for successful projects.

The core team helps organizations return to a customer focus. During the Industrial Revolution, organizations were built around repeat processes that made repeat products. While concentrating on the product, they lost sight of the customer. It was then required that the customer understand the product and devise appropriate uses for it. This was certainly the way with early computer products: they were bought and then programmed by the buyer to fit the needed application. But the Industrial Revolution has given way to the customer revolution, and these customers now demand applications and solutions to problems, not just products. Satisfying this demand requires a return to the old guild approach, where one person worked with the product from the beginning through the customer application (see Box 4.1). However, modern products and applications are too complicated for just one person; they require a team in place of a single craftsman. The modern craftsman is thus the core team.

Led by a project manager and responsible for project success, core teams represent the departments involved in bringing a product from concept to customer. The members are people with complementary skills who are committed to the goal of the project and hold themselves mutually accountable for it. Thus, they take the time to render their best judgments on important issues. As team members develop, so does the team; eventually, it is able to apply a collective wisdom that is so important to eventual project success. Developing this collective wisdom may be expensive, but the results can be priceless.

Core teams represent a return to the guild approach to production that was common before the Industrial Revolution. Core teams are also a response to organizations that were developed as a result of the Industrial Revolution. Note that the bureaucratic organization was a replacement for the guild system. Efficiency came with standardization. Now that we are returning to a modified guild system, we will give up some efficiency but will gain customization. With the guild approach, one craftsman would make customized products to fit the requirements of the customer. The craftsman had to understand the customer, the product, and the customer’s use of the product.

Source: Adapted from Graham (1984).

Developing a Core Team Process

For the upper management team to develop a core team process:

• Require that each project have a core team.

• Define core team membership as an important position in the organization. Commitment to the core team should be full time or at least a large percentage of each member’s time.

• Support core team involvement in defining the project goal and completing the project plan.

• Heavily involve core team members in the project start-up meeting.

• Resist moving core team members once they are assigned.

• Motivate, evaluate, and reward core team membership.

• Support regular core team meetings.

A common mistake in implementing project management is ignoring the process of developing core teams. Core team process implementation requires a long-run view of projects; often only upper managers have this view. On occasion, the project manager is told to plan the project, or just to get started and then bring people on board as necessary to accomplish the project work. This invites disaster: it propagates another version of the over-the-wall problem, complete with lack of team buy-in and difficult communication problems.

The typical excuse used to justify the as-needed approach is that people are busy and that it costs money to have them involved when they are not needed. Granted, these people are busy, but often what they are busy doing is putting out the fires lit by the last project, or they may be busy working on projects that should have been completed long ago. Most projects take about one-third longer than they should, or one-third longer than they would if they were properly staffed and motivated—and proper staffing includes the use of a core team. Not using core teams because people are too busy is a circular excuse: people are not on core teams because they are too busy, and they are too busy because they are not on core teams.

The circle needs to be broken. Doing so requires the intervention of upper managers who have a long-term view of the importance of project management. Yes, core teams are expensive, and yes, assigning people full time to them may seem extravagant, perhaps even requiring a temporary increase in organizational staffing levels. However, the long-term benefits of core teams, including increased quality and decreased cycle time, can easily pay for the temporary higher expense. Upper managers need to know and believe in the benefits of core teams in order to develop the strength and resolve to implement them.

Core team membership becomes important when people get motivated to participate. The first North American woman to reach the summit of Mount Everest, Sharon Wood (1996), described the process she underwent to get accepted on the team of thirteen Canadian climbers. In front of other potential team members, she responded to three questions:

1. Why do you want to climb Mount Everest?

2. What can you contribute to the team?

3. What do you hope to gain from this experience?

In thinking about these questions and answering them in public, she experienced an attitude change at that moment from curiosity to commitment. Taking a lesson from this testimonial, some groups now use a similar process to gain commitment from core team members, especially on large cross-organizational projects. During the project start-up meeting, they describe why they want to be on the team, what they can contribute, and what they hope to gain from the experience. The results are an increase in motivation, a sharing about expectations, and inputs to management about rewards that will motivate team members.

Benefits of Core Teams

People in organizations that do not use core teams may be unaware of the many benefits accruing from their use. Following are some of these benefits.

Core Teams Reduce Cycle Time. Some may argue that having all departments involved from the beginning of a project wastes money, but it actually saves money in the long run. Core teams cut cycle time and so they complete the product faster. Given the concept of life cycle (described next), the organization needs to aim and get a quality product to market as fast as possible to maximize its potential.

In the past, people considered a product to have a particular life cycle that would achieve a certain level of sales no matter when it was introduced. The example in Figure 4.3 shows a typical life cycle of slow growth, rapid growth, leveling off, and decline. The shaded area under the curve represents the total sales the product could expect. However, it is now clear that products are examples of a certain concept and that the concept itself has a certain life cycle. Products that represent that concept and are introduced early in the concept life cycle have greater sales than products introduced later in the concept life cycle. For example, consider the IBM Selectric (bouncing ball) typewriters. This was a concept in typing and word processing that used a movable and replaceable typeface ball. At one time, these typewriters were commonplace, but the concept life cycle turned out to be about fifteen years; it was replaced by dot matrix printing (itself later replaced by laser and inkjet printing). The bouncing ball typewriter concept finished its life cycle, and introducing any product based on it now would be folly.

FIGURE 4.4 Concept Life Cycle

To maximize profit potential, a product must be on the market as early as possible in the concept life cycle. Figure 4.4 shows the sales potential of a product introduced at the beginning of the concept cycle; the darker portion shows the total sales potential of a product introduced later in the cycle. Potential sales at that later stage are much lower because the concept that the product represents completes its cycle soon after the product is introduced. According to the oft-quoted McKinsey study (Smith and Reinertsen, 1997), a project that is late for an amount of time equal to 10 percent of the projected life of the product will lose around 30 percent of the potential profit. A project that goes 50 percent over budget but is delivered on time will lose about 3 percent of the potential profit. Many restrictive assumptions were made in the McKinsey study, so the numbers quoted should not be taken as absolute projections. But they do indicate that a significant amount of additional profit may be gained by being fast to market and that this profit often outweighs by several times the extra costs incurred in speeding to the market. Therefore, the core team that helps deliver a product nearer to the start of the concept life cycle does not waste money; rather, it generates money by increasing the potential for profit.

For example, Cadillac (1991) found that by creating interdepartmental teams in its simultaneous engineering process, it could reduce the time taken to make automobile styling changes. A process that took 175 weeks could be done in 90 to 150 weeks, allowing new models to be on the market much faster.

Core Teams Increase Quality. Being first to market is not beneficial unless the product is top quality and meets or exceeds customer expectations. It is not just quickness to market that counts; being first to gain customer mindshare is becoming more evident and important, such as how Microsoft Word and Excel overtook Word Perfect and Lotus 1-2-3. Mindshare results when the majority of the target market thinks of your products first and believes that your company offers solutions that other companies must measure up to. Creating mindshare requires a dedication to quality, and creation of interdisciplinary teams with a customer focus is one of the cornerstones of quality management. Core teams serve that purpose on projects.

In addition, core teams that cut cycle time add to quality in other ways. The arguments for faster product development cycle times through faster learning have recognized that productivity gains can improve not only cycle times but also product capabilities and quality. This is because core teams reduce hand-offs from one department to another, reducing the information loss and quality decreases such hand-offs might otherwise cause.

Core teams also help implement a marketing-customer orientation. Because the team is involved “from concept to customer,” a representative from the marketing area should be on the team. Exposing team members to marketing concepts heightens focus on the customer for the whole team. Perhaps even a customer or customer representative might be involved with the core team, either as a member or through a focus group. In any case, the final project goal developed by the core team should have massive customer input, perhaps through quality function deployment techniques. Also, teams should follow Total Quality Management or Six Sigma guidelines to help ensure quality.

Core Teams Develop Better Project Plans. The core team refines project objectives, develops strategies for meeting those objectives, identifies critical resources, and develops the plan for the project. The plan becomes the daily guide to action for members of the project team. The core team should always be involved with the project manager in the planning process, so upper managers ought not to try cutting planning time by instructing the project manager to do it quickly and alone. Core team participation may take longer, but there are benefits.

By participating in plan creation, core team members better understand the goal of the project. A customer-driven requirements document helps set the project goal. A common, well-understood goal is a part of the team-building process that leads to a successful project; such a goal also helps reduce cycle time. In addition, core team participation in the planning process allows members to work with each other before the project begins, building trust among them that can develop further as the process proceeds.

Such participation also helps ensure that all necessary project components are considered, reducing the chance that something important is overlooked until near the end of the project. All core team members need to know when to schedule help, from inside or outside the organization, to aid in deciding issues that fall in their area of expertise.

Upper management needs to encourage the project manager, the core team, and the project sponsor to hold a start-up meeting, sometimes called a project launch. It is important for developing a shared vision and for communicating, team building, and building relationships with stakeholder groups. Also, it can and should be used to develop trust among individuals and organizations and to define clear roles and responsibilities so that work can proceed. This is also the time to decide on decision making, conflict resolution, and escalation processes. Experience shows that upper managers need to demonstrate support for the project during the start-up meeting but also allow the team to define how it will accomplish its goals.

Core Teams Can Overcome Organizational Design Problems. Without a core team, the final product may reflect the biases of organizational design, a problem inherent in organizations composed of highly autonomous divisions. As Bowen, Clark, Halloway, and Wheelwright (1994b) explain, when the HP 150 personal computer was first designed, four divisions were involved, each focused on a particular product line. No core team was developed, so overlapping projects arose. Senior management leadership was inconsistent. Because marketing was not involved early in the process, no one was sure if any customers really wanted the product, and critical components such as the keyboard and the disk drive were not high priorities for the divisions that made them. As a result, the final product reflected the independence of the divisions that manufactured the components and lacked a unity of purpose and design. The product was not a failure, as it allowed HP to get started in the personal computer business, but it did not live up to its potential.

Bowen and his fellow writers contrast that with the highly successful HP DeskJet printer project, which skyrocketed the company into the inkjet market. This project used a core team almost from the beginning. The marketing department was involved early, and there was consistent top management support. All team members were collocated, and engineers worked closely with the marketing department and with end users: “The team produced a well integrated product because its members were located together for the duration, and they were an integrated bunch” (Bowen, Clark, Halloway, and Wheelwright, 1994b, p. 423). In this case, the use of a core team helped mitigate the organizational design of independent divisions and so produce an integrated product.

Core Teams Encourage Creativity. Core teams are creative. Because they have members from different departments with different points of view, these teams embody requisite variety—the concept that creativity is encouraged when a variety of points of view combine to address a particular problem. It is not that teams of people from one department cannot be creative; rather, cross-departmental teams tend to have a larger variety of viewpoints, which encourages creative solutions. The principle of requisite variety states that having a number of different views fosters creative ideas. Requisite variety is a biological principle based on observations showing that species lacking enough variety and diversity tend to wither and eventually cease to exist.

Variety in team membership also makes teams more difficult to handle, so upper managers who support team training and provide the opportunity for extensive networking and robust interactions get greater creativity from core teams.

Core Teams Make It Possible to Develop Technical Expertise. To be successful, a team needs to use existing organizational expertise to produce a final product. The project manager may not have this technical expertise, so it must reside in the core team. Companies need people who can do two things effectively: serve as team members and lead the effort within their functions. Core team members do exactly that; they are themselves members of the project team, and they are responsible for directing the work of other team members. Core team membership is thus a pivotal position and should be highly regarded in the functional departments.

An important factor in making core team membership appealing is the existence of a dual career ladder in the organization. This means having two ways to advance in the organization: climb the traditional career ladder into management or climb a technical ladder and become a chief technical contributor. Consider adding a project management ladder. Core team membership is ideal for technical contributors: they can remain in their technical specialty and be part of the team without having to manage it, and they continue to develop technical expertise while contributing to team projects. (See Chapter Seven for more on dual career ladders.)

Core Teams Execute Project Plans. Once plans have been established, the core team oversees the completion of the project, primarily by involvement in exception management and risk reduction.

Ellis (1994) described his experience with a core team at HP as follows: “The teamwork and alignment of the members of the core team is critical. This team will spend many hours together and will face many difficult challenges together. The project team and management group will look to this group to provide leadership. The extent to which we get ’out of our silos’ [see Chapter Five] and act as a team will play a large factor in success or failure. We have had several of-site meetings with a variety of team building activities. We also have had a ’process quality consultant’ available to help plan and address local teamwork issues.”

Note that working on core teams, as well as upper management behavior in general, often consists of turning the biggest opponents into allies. Planning creates team development and involvement; grief results if effective planning is skipped over.

When variances from plans and specification occur, as well as when new risks present themselves, established core teams move quickly to determine appropriate responses.

Functions of Upper Management

Core teams are difficult to implement unless all upper managers agree on the concept of core teams (relatively easy) and pledge to do what is necessary to make it work (much more difficult). This is often a classic ends and means problem: everyone agrees on the ends, but no one can agree on the means.

One barrier is that implementation limits upper managers’ freedom of action. If a person from a given department is put on a core team, that person is not available to the departmental manager until the end of the project. The departmental manager cannot pull the person off one project to work on some other “hot” one, as core team membership is defined as an obligation to work on the project from beginning to end. A person from R&D, for example, would stay with the project until the day the product ships to the customer, and maybe beyond, depending on the definition of the end of the project. Members of the upper management team need to stand ready to limit their departmental prerogatives for the good of the organization as a whole. If they do not, the core team concept is doomed to failure.

Upper managers can again look to their own behavior for clues about creating an environment for successful multifunctional teams. Meyer (1993) describes good executive sponsors of teams as being like good driving instructors: they teach and guide without grabbing the wheel unless the situation is life threatening.

Sponsors help build capabilities and processes within the team to achieve the goal rather than solving problems directly. Meyer (1993) goes on to say that the critical roles of executive sponsors are teaching upper managers how to work with teams, transforming their own functions into centers of expertise, and learning how to lead a team-based organization: “It is very difficult to comprehend fully how these teams actually work until you’ve been on one. Making functional leaders sponsors enables them to see firsthand how the teams work and what they must change within their function to support them. Those who do not serve as sponsors miss this experience and rely on anecdotal reports picked up in hallway conversations” (p. 127).

Englund and Bucero (2015) provide further details about selecting sponsors as well as defining their role and development plans.

To implement a core team process, upper managers are advised to consider each of the following.

Develop Project Priorities. Establishing project priorities is a first essential step, as discussed in Chapter Two. When upper managers work together to establish these priorities, they help core teams operate across organizational boundaries. This is important because core teams by definition cut across departmental lines. Any dissension in the ranks of upper management will be reflected in the behavior of the core team. If a given project has a different priority in each contributing department, the team members will reflect those priorities and have difficulty acting as a team. Thus, the project should have the same priority in each of the contributing departments, and that does not happen unless upper managers support the core team concept by defining project priorities.

Define the Core Team Concept as Important. Upper managers too often indicate the desire to cut cycle time and increase quality even as they deny project managers the means to attain those goals. The upper management team can support project managers by publicly declaring that the core team concept is important and will be implemented in the organization. When this is done, project managers can better implement the concept.

Agree on Assignment of Core Team Members. If upper management is serious about cutting cycle time and increasing quality, it will assign full-time core team members— usually. Some small projects may not warrant full-time assignments, but team members on these projects should still be occupied on them a majority of the time. The percentage of time may vary for each individual depending on where the project is in the process. However, the same people need to remain on the team. For the core team to function effectively, its members need to be released from some departmental duties—that is, from “billable hours.” Upper managers of contributing departments also need to realize the importance of the core team role and agree to the release so that members are not penalized for joining the team.

Normally, one project manager leads the team. It is possible to have rotating leadership within the core team. When this is so, the rotation should not come as a surprise; all project managers should come from the core team, and all should return to regular core team membership after leading it. At Allen-Bradley, for example, “in general, leadership of project teams rotated according to where the project was in the milestone process. Marketing assumed the lead role for the business proposal and project definition segment, up through the first GM (upper management) milestone review. Engineering then guided the team through the design and development phases, followed by manufacturing’s lead during pilot activity and full production. Marketing took over again for field performance reviews and the final GM evaluation, which occurred six months after the first shipment” (Heckscher and Donnellon, 1994, p. 249).

In general, project leader rotation from the core team can be done by assessing the key risk being encountered by the project at a given time. If marketing success is the key risk to project success, perhaps a marketing person should be the project leader. If technology is the key risk, consider a technology leader. Select a leader with talents and abilities strong in the skill sets required to overcome important risks, notably “soft” people skills (see Englund and Bucero, 2019).

Resist Pulling Members Off the Core Team. Pulling people off the core team negates the entire concept. Cycle time is lost as new members must be trained and brought up to speed. Quality is lost as new members do not know the effects of decisions made before they joined or the effect that future decisions will have on previous decisions or on other departments. Thus, loss of continuity causes loss of both time and quality, the prevention of which is the very reason the core team was established in the first place.

Many upper managers attempt to mitigate the negative effects of pulling a core team member by replacing the person with someone of equal skill. But people are not interchangeable parts (see Figure 4.5); the assumption that they are may stem from managing departments where people do work that they have done many times before. In such an environment, there may indeed be only minor consequences to substituting one person for another, and the practice may even be considered good management, a way to maintain upper management flexibility at little cost in efficiency. A project environment, however, involves knowledge work, and such substitutions can cause major problems and setbacks; rotating core team membership is often cited as a major factor in project failure. Thus, upper managers best enable project success by developing the discipline to resist pulling members off the core team.

FIGURE 4.5 Core Team Members Are Not Interchangeable

Motivate Core Team Membership. Core team members’ attitude toward the project role is strongly influenced by the manager of their home department. If the department director is negative about it, the team member may carry that attitude into the team. Negative attitudes have a way of becoming self-fulfilling prophesies. According to Katzenbach and Smith (1995, p. 45), “Unbridled enthusiasm is the raw motivating power for teams.” Upper managers and department directors need to show enthusiasm for project work to help motivate the core team.

Encourage Creativity. Upper managers need to be certain that people know that taking risks is okay. They must also drive out fear and create trust. This is often difficult to do in projects, given the triple constraints of schedule, outcome, and costs. However, upper managers can help in the following ways:

• Schedule. Project deadlines can be helpful in motivating completion of creative work. In fact, most creative work is done to a deadline. But it must be a believable deadline, and for core team members to really believe in it, they should be part of the deadline-setting process, as discussed in Chapter Three. People are not motivated by artificial deadlines.

• Outcome. This is where the excitement of creativity lies in a project. Creativity is often needed to meet customer expectations and help solve customer problems. Upper managers encourage it by facilitating core team contact with customers and encouraging creative solutions to customer problems. Upper managers can help by finding blocks to creativity in the organization and eliminating them for project teams. Look for triggers—key defining events that excite involvement and turn mild curiosity into commitment. These events are usually experiential; it is not usually possible to dictate them. Encourage team members to get firsthand unbuffered exposure to the source of urgency for the project, such as a customer’s mission-critical problem. For example, many R&D managers encourage their engineers to go with marketing representatives on customer visits. When they do, the engineers often discover creative ways that their products are being used and often learn of new customer needs.

• Budget. Research and experience indicate that one of the biggest barriers to creativity in organizations is overreliance on budget as a guide to action. Strict adherence to the budget may be sound practice in repeat process and product environments, but it is a creativity killer on projects. Stopping ideas because “they’re not in the budget” sends a message that standard, safe thinking is wanted on projects. Certainly, some projects that are very creative end up costing too much because of it. The key to avoiding this problem is to manage creativity; the actual cost of a creative solution is not as important as its effect on the final product. Continually direct thinking toward the final product, not toward the specific creative solution itself (see Box 4.2).

Stress Interdependence. Upper managers can help make the core team system work by constantly stressing team members’ interdependence, a factor that leads to achievement of core team benefits. When a core team system is initiated, many of its members will be accustomed to working alone or in their own departments. Some managers purposely create scenarios that require interdependent actions.

Some people may feel more comfortable working alone than on a team. When reviewing team output, upper managers help by constantly asking how well the members have been working as a team. They also need to build a strong performance ethic and establish metrics for teams to measure performance. The project sponsor needs to meet with the core team often and review team output.

BOX 4.2 Creativity and Budgets

Computer simulations have been used in project management training for many years. During a simulation, teams choose among the most effective and often the most creative ways to solve typical project problems. Some organizations clearly make choices that rely on budget; they do not choose the most creative options, even though the team may want to, because these options are not in the budget. Questioned about this behavior, these teams invariably mention that their upper managers measure them on budget, not profit. Thus, if a more creative solution increases profit, the team does not benefit from it, and if the solution increases spending, the team feels the negative consequences. The net result is that many creative solutions are ignored.

Provide an Environment to Support Teamwork. As previously mentioned, it is best for core team members to be collocated. The best environment for teamwork is where all team members are in the same area and interact daily. This enhances both team spirit and team communication. When collocation is impossible, a good environment can be approximated by providing a room that is available to team members at all times—a project, or virtual, room where they can meet, interact, and do project work. If having a room of their own is impossible, space should be designated so that the team can meet at the same place, at the same time, on a regular basis. This is a minimum environment to support good teamwork.

In addition, much technology is available to help teams function. Linked computers with email, shared files, project intranets, notes, and the like are just a start; core teams whose members are far apart should have access to facilities for conference calls and video conferencing.

Staff Teams for Success. From extensive research on why management teams succeed or fail, Belbin (2010) reports that the classic mixed team is the most reliable variety of those studied. A team can more often find among its members the characteristics necessary for good management and leadership; few individuals possess all such characteristics. A winning team starts with a successful chair (project manager) who is patient but commanding, generates trust, and looks for and knows how to use ability in others. The team includes at least one very creative and clever member as well as at least one other possessor of a lively mind of similar caliber for the former to bounce ideas against. According to the research, teams where the remaining members have a wide range of mental ability pull together better than more intellectually homogeneous ones. Winning teams have a wide range of strengths to draw on and a good match between the attributes of members and their responsibilities. One team member or another should be suitable for any job that comes up, or the members should have the flexibility to adjust to and fulfill roles other than their primary ones. The research illustrates that a single addition to a management team can change the fortunes of a company, and a single subtraction from the team can have a momentous negative effect unless a balance is reestablished.

Change the Reward System. The goal should be to make team membership rewarding. Beware of talking teamwork but rewarding people for individual contributions. Design a variety of rewards and apply them according to needs and context (more about rewards later).

Create Psychological Safety

New research reveals surprising truths about why some work groups thrive and others falter. Reported in “What Google Learned from Its Quest to Build the Perfect Team” (2016), after spending copious amounts of time and money, Google determined the best approach was to create psychological safety, faster, better, and productively:

• Encourage conversational turn-taking and social sensitivity

• Discuss norms for group interactions—a common platform and operating language

• Develop a shared belief that the team is safe for interpersonal risk taking

• Build a sense of confidence that the team will not embarrass, reject, or punish someone for speaking up

• Cultivate a team climate characterized by interpersonal trust and mutual respect in which people are comfortable being themselves

Psychological safety, more than anything else, is critical to making a team more complete or near perfect.

Developing a Team Reward System

Probably the most difficult aspect of supporting core team development is changing the reward system to recognize the work of teams. Most organizational reward systems are deeply rooted in the bureaucratic assumptions of individual rewards for individual work. These assumptions require a narrow division of labor and a hierarchy of levels where an increase of level in the organization is rewarded with an increase in compensation. With experience, it is gradually being understood that the narrow division of labor and the vertical ordering of titles and authority do not tend to support teamwork. In addition, merit-based pay is theoretically tied to individual contributions to the value added by the firm. It is normally not based on team contribution. Because of this, most organizations end up extolling the virtues of teamwork but rewarding people for individual contributions. Heckscher and Donnellon (1994) say that because reward for individual contributions is seen as fair and desirable in the broader culture of the United States, the reward structure may be the most difficult aspect of an organization to change in pursuit of postbureaucratic organizing.

DETERMINING OUTCOMES TO BE REWARDED

There are several factors to consider when changing the reward system. The first is what behavior or outcomes will be assessed and rewarded. Upper managers need to define the criteria for success and make them very clear to all project team members. For projects, they should be based on the project goal statement. For example, is the team to be held responsible only for delivering the product or also for the ultimate profitability and support of the product? Is the team responsible for initial production of the product or for ongoing production? Base the reward system on accomplishment of the project goal, and make it public. Everybody on the team will then know what the rewards are and how they are administered.

Additionally, are all members of the team, or just the core team members, to be held responsible for product success? Typically core team members have greater responsibility for ultimate project success because they are the ones on the project from beginning to end. If they have greater responsibility, they can expect greater reward with success and greater disappointment with failure. Base evaluations of everyone on the team partly on total team performance.

Most important, determine a system of rewards before teamwork begins and make it clear to all team participants. A best practice is to ask teams and individuals what rewards they find important. Tremendous variability exists about how people view rewards, so asking them indicates care and respect for differing points of view. Also, be sensitive to the cultural variations that exist around recognition in public.

REWARDING TEAMWORK IN REACHING OUTCOMES

Individuals need to be rewarded for their contribution to teamwork. Most systems reward individual contributions, not teamwork. But if teamwork is desired, it should be rewarded; reward should be made for the behavior desired. The difficulty for managers in assessing individual contributions to teamwork is that they do not observe such behavior. A typical solution is to have team members assess each other’s contribution to team performance. Of course, it is easier for core team members to assess each other if they are a continuous team. Members who come and go may do their part without full knowledge of other individuals’ contributions. When this is the case, it may be possible for core team members to assess the work done by regular team members in their areas.

The important point is that upper management creates metrics that support and measure desired behavior; you get the behavior you measure. Make the metrics as objective as possible, and ensure that the criteria for a certain reward are known in advance so that people can strive to meet them. One example of a good metric for teamwork is given by Carlisle (1995). In the example, the upper manager wanted to develop teamwork among the refinery managers who reported to him. During weekly status meetings, team members reviewed operations and any problems that they had. They talked about the decisions they made to solve the problems and who on the team helped them solve the problem. When the manager was away, he picked as temporary manager “the man who is most often referred to as the one my subordinates turn to for help in dealing with their problems” (p. 76). When upper management positions became available, the manager also recommended this person for promotion.

In this example, teamwork is promoted by requiring team members to ask each other for help when they find problems. The upper manager literally refuses to help with problems until his subordinates consult with other subordinates. The metric is fairly simple: it measures how often people are referred to as helping others on the team. Of course, most upper managers do not have all team members doing the same or similar jobs as in a refinery; many different departments or functions are involved. However, from the perspective that all problems are team problems, such a metric could be effective in other settings as well.

DESIGNING NEW EVALUATION PROCESSES

The project manager needs some control over the process of evaluation and reward, an important lever that can be used to motivate team members. One part of motivation is the intrinsic value of the project. Another is being included in the performance review at the end of the project.

If team members feel they will not be recognized in their departments for good project work, they will view joining a project as a risk. Thus, the project manager needs to be part of the performance review process. One way is for team leaders to provide feedback to functional or department managers who are responsible for writing performance evaluations for the people on the core teams. Base reviews on both individual contributions and teamwork, and have a section on the review form for evaluation of teamwork that grants it equal weighting with, if not greater weighting than, individual contributions.

This does not mean that the project manager takes over the performance review process. It remains the purview of the department director or, if there are no departments, of one person assigned the function for project team members. The person designated to do performance reviews should gather information from the project managers and other people with whom the individual works.

The project manager needs significant review input for the time people spend on the project, particularly that of core team members. This manager can fill out a detailed performance appraisal for each core team member that includes appraisals from other team members regarding the teamwork displayed by the individual. If possible, the project manager sits with the department director or other designated person during the project part of the performance appraisal. The core team members fill out performance sheets on other project team members in their areas, reducing the risk that team members might be penalized for their project work.

When upper managers appraise the performance of their project managers, stress not only the success of the project but also the project managers’ teamwork with other project managers to implement organizational strategy.

In addition, stress that individuals retain responsibility for their self-development and career management. Some organizations develop objectives for people development. Essentially, each person needs to take the lead in determining what he or she needs in a development plan: courses, conferences, reading, mentoring from others, or coaching from management, for example. Management has co-responsibility to respond so that both parties, manager and subordinate, work together on people development. Career self-reliance is an important ingredient in building accountability in an organic organization.

DESIGNING NEW REWARDS

Additionally, upper managers need to consider new rewards for good performance. In the past, it was usually assumed that performance was rewarded with pay or promotion, or both. However, not all rewards take these forms; furthermore, base promotions on the ability to do the new job, not on performance on the last one.

Even mediocre teams may have one or more outstanding performers. Such individuals can be rewarded with “most valuable player” recognition despite the team performance. If superior individual performance needs to be rewarded, consider bonuses and stock options. Reserve promotions for those who clearly can handle the job at the next level, not just those who have superior performance at the current level.

Many rewards are intrinsic in project work itself, such as recognition by senior management, learning a new skill, working at something new, working with different people, working in a new location, or having the ability to travel. One of the best rewards for project managers and team members is to get another good project or a larger project and continue doing what they enjoy doing. Different people like different rewards, and different people are motivated by different things at different times of their lives. The important thing is to have a variety of rewards, apply them according to needs, and allow the project manager to use some rewards to enhance team motivation. Some organizations enable individuals to award $50–$100 to other individuals in recognition of contributions to the project.

Steele (1989, p. 151) commented on this factor when discussing dimensions of reward systems in project management: “[One] dimension is allowing the project manager to have control over the process of reward. If the project manager cannot determine or at least strongly influence recognition and compensation, he faces an almost impossible task. Inability to promise and deliver rewards commensurate with contribution is a major barrier, even to recruiting capable people to work on projects, much less to motivating them to intense, dedicated effort. Being farmed out to a project, even a high-priority one, can make one an orphan when it comes time to reward performance—and it is a painful experience.”

Team Development

Teams in general are important for project success. In the project environment, do you favor collaboration or competition? The competitive spirit is present in most of us but can be destructive when trying to get people to communicate and work together. A piece of advice from a manager was to compete aggressively against other companies outside our own and to collaborate within the company and on our projects. Competition to collaborate better could be a good thing. It often is good and effective to encourage individuals to compete against themselves in order to perform better.

It is extremely helpful when executives articulate organizational values, in areas such as integrity, dealing with competitors, and customer satisfaction. Project managers are wise, when initiating projects, to specify in a project charter or business plan how the project supports those organizational values. Also set expectations for team behaviors. During project start-up activities, verify that personal values are in alignment with team and organizational values. Put time on the agenda to share and discuss these topics. This will be time well spent to develop alignment and ward off possible conflicts. Also develop a shared vision about a desired future state when the project is completed. Do this for each project, using team discussions to both craft and refine the vision. Use vivid language and a compelling description that is unique to the project. Diversity in how to implement the project is okay, but strong disagreement may warrant replacing certain team members.

There is a not too subtle distinction between incentives and rewards. An incentive is announced in advance that something will be offered as a reward if a goal is met. Rewards are presented after an achievement is met. Rewards may either be known in advance or come as a delightful surprise.

The problem with incentives is that, if conditions such as economic downturns occur that no longer make it feasible to fund a reward, or if circumstances beyond a team’s control make it unable to meet the goal, people may be demotivated if the promised incentive is not fulfilled.

Our suggestion is to focus on rewards, make them appropriate to the people and the context, and be wary of incentives. Rewards that come from peers—team members— are often more valuable and less problematic than those from management, which could be biased, ill informed, or perceived incorrectly as supporting favoritism. A good reward for individuals could be based on those who helped their colleagues. Reward individuals in private and teams in public.

A suggestion for virtual teams is to put extra effort into the personal touch. The more you use high tech, the more you need high touch. Get people to share aspirations, interests, goals, and preferred ways of communicating. Encourage storytelling to demonstrate points of view. Stories about customer interactions or needs help immensely when deciding on features in new product development.

One key element that accelerates team development from forming to performing is for team members to listen to each other. When observing team members participating in project simulations that we conducted, many people, especially the aggressive types, tended to pick answers quickly and push to move on. The quiet types, who were still contemplating the scenarios, did not have an opportunity to speak up. Mistakes were made before people realized they should take more time for discussions, hear or draw everybody out, and proceed only when consensus is reached.

International and Cross-Organizational Teams

Employees at overseas branches often complain about the home office, saying things like, “We tell them everything. They never answer our letters, so we don’t know what’s going on in the States.” The headquarters’ response is, “They don’t listen, they don’t answer our letters, so we don’t know what’s going on over there.” Each believes it is sending lots of information to the other and getting little in return. Clearly, neither has defined what information the other side really needs.

The “distance doctor,” Jaclyn Kostner (1996), focused her work on describing how global or international teams can be effective despite the difficulties of bridging the distance between team members. In communicating, she advocates asking who is remote: you or the other team members? It depends, of course, on who is asking the question. Management may believe that empowerment means giving power to remote teams, but there is no guarantee that cooperation will take place. Instead, be prepared to gain access to the power possessed by others who are leaders of their own teams (see Box 4.3). You cannot, says Kostner, give away power you do not have. Success as a project leader comes from capturing power, not giving it away. Realize what contributions are needed from others, such as technical expertise, previous experience, or access to markets, and capture their power by establishing clear agreements on vision, roles, and responsibilities. The upper manager becomes a leader of leaders.

BOX 4.3 Why Empowerment Is Not Enough

When James Kirk, captain of the starship Enterprise on the original science-fiction television program Star Trek, went on a mission from the orbiting starship down to a planet, was he remote from the starship or was the Enterprise remote from him? In essence, the question is irrelevant because clarity of roles and the ease of communication kept the relationship continuous. Captain Kirk did not give power to the second in command while he was on the mission; rather, he put them in charge of the resources. When Kirk commanded, “Beam me up, Scotty,” in order to be tele-ported back to the ship, he drew not on the empowered team but on the ability of the crew to engage the resources or power of the starship. (Of course, one could question if “upper manager” Kirk was foolish for leaving the ship instead of delegating the hero role to his project managers.)

Kostner goes on to describe the glue that holds remote teams together: developing a powerful shared vision that vividly describes the end result expected. Look for evidence that people use this vision as “intellectual cohesion” that permeates all communications. People need to make the extra effort required to check and recheck for understanding about where they are going. Be clear about what is expected from remote team members. Upper managers need to demonstrate a commitment to developing trusting relationships early in the process and maintaining them throughout the project. This means putting equal or possibly more attention on relationships than on tasks. Upper managers need to be clear about and reinforce through their own behavior the need to meet the “prime directive” that the team sets out to accomplish.

How do you build trust with people who work of-site? Because other people look to leaders to organize the work, leaders break the trust when they are not clear about the work. To correct this situation, start by giving a visual anchor—a way for people to visualize the end result. Then provide a hands-on anchor: a small model or prototype. Continue with a word anchor that provides a description, definitions, and comparisons. A decisive step in creating crystal clarity is to create a clarity partnership, where both parties commit to work together to create understanding.

Addressing the topic of project and program management for large projects across organizational boundaries, former HP executive vice president Rick Belluzzo (1996a) advised being “very focused; pick those opportunities that you think have the greatest return, organize around it, but recognize it’s going to take a lot of leadership, it’s going to take a lot of getting around, talking to people and really working to develop an overall strategy that people can act on. That’s what works best at HP. When you get a strong message out there that’s very clear, people implement in incredible ways. That’s a real strength of ours!”

Collocated teams are best, but if they are not possible, the teams should meet at a regular place at a regular time. For international teams, this is not always possible, so they can use conference calls or video or Skype-type calls. However, team members have to meet face-to-face to see eye-to-eye. Therefore, support occasional face-to-face meetings of international teams. They should meet at the beginning of the project, then perhaps every six months, and again at the end to wrap up and celebrate. Remember that the intent is to approximate the ideal, not to save money on airfare. Although it is important to plan face-to-face meetings carefully, the time apart should not (but often does) get short shrift; we are not as good at communicating at a distance. Recognize that remote team members thrive on information about the project and the company by supporting efforts that sustain and enhance the project management information system.

In the case of self-managed teams, know that core teams for projects do not run well without a recognized project manager. Self-managed teams run well when the process they are working on is well known, the objective is clear, and little cooperation is needed from outside the team. But this is usually not the case in projects, so a leader is needed. The enthusiasm generated by members of a self-managed team can result in the silo effect experienced by departments, such that team members become loath to work with outsiders. The project manager provides the liaison and ownership for the “whole product” result that facilitates collaboration among teams. Agile teams are newer examples of self-managed teams that operate successfully with some degree of autonomy.

Telecommuting is an increasingly interesting option for enhancing employee productivity while adjusting the demands between work and life. Managers are advised to sit down with employees and determine whether telecommuting really makes sense. As part of being a modern employer, delivering flexibility means to favor making equipment available so people can stay home a day or two a week. Do not get caught up in the issue of cost; it may be possible to balance the price of equipment, home loans, and other creative approaches against savings at the work site. These approaches give people an incentive to stay, helping the organization avoid the costs of finding and recruiting replacements and bringing them up to speed. A work options program manager added, “We’re moving from an approach where telecommuting was seen as a reward for top performers to more of an integrated business approach that balances an individual’s need for flexibility with HP’s business need” (quoted in Platt, 1996).

Moskowitz (1996, p. 64) commented:

Telecommuting and “hoteling” of offices [may produce] hidden advantages. For example, employees who are less tied to fixed workstations tend to lose their focus on intra-office concerns, such as procedures, politics, protocol, and rivalries. They stop jockeying for corner offices and turn much more of their attention outward, toward the customers they’re serving and the work-related goals they’re trying to achieve.… Among the many things telecommuters have successfully proven is that much of today’s work can be “deconstructed” into individual elements, accomplished by various individuals working at separate times and locations, then reassembled again into a finished deliverable with great savings in time, effort, and expense.

The international presence enjoyed by multinational companies means that the sun never sets on some projects. It is increasingly possible for project work to happen by day in one country and to continue by night in another. Such nonstop work is one way to shorten cycle times. The environment to make this happen requires good project plans, clearly defined roles and responsibilities of people and their counterparts in the other country, and advanced communication capabilities.

Electronic meeting rooms are increasingly more readily available; they allow core teams to conduct brainstorming sessions from remote sites. Team members may be at home or across the country and still connect into a central system. A question is posed on the computer screen, and people type in ideas that are visible in a common space on the screen to provide inspiration for further ideas. After a while, they may be asked to vote their preference for certain options. Technological tools such as these can help dispersed teams reap the benefits previously available only to in-person teams. Electronic meetings, however, are still weak communication vehicles.

To make cross-organizational and international teams work requires understanding cultural differences. People’s actions, reactions, and perceptions are more often driven by their cultural values or shared beliefs as a group than by almost any other factor (Mead, 1990). Cultures may vary across disciplines, companies, and geography (Leonard-Barton, 1995). The differences may be frustrating at times, and they often slow progress, which may make some people view them as project liabilities. However, the benefits derived from the project outcome being applied globally may be massive. Upper managers can take the lead by viewing cultural differences as assets—ways of embracing a broad customer base—and seeking a shared understanding of those values that can lead to a result desired by all. Working with other cultures is not intuitive; people are genuinely different, and one’s own experiences may not be preparation for understanding the thinking and actions of others. Upper managers support cultural diversity on projects by preparing and encouraging others to understand diverse cultures through asking questions, taking courses, reading, learning from others who work or have worked in other cultures (cultural informants), and immersing themselves in other cultures for sustained periods.

Belbin (1996, p. 136) summarizes the process: “Establishing the right climate in which well-designed teams can form and flourish is the foundation stone on which more effective teamwork in the future can be built.” In addition to the principles, concepts, methods, and techniques he uncovered for designing successful management teams, Belbin adds, “what turns team-building into an art is that the bricks, like legendary men, are made of different types of clay and not wholly predictable after firing.”

Using Net Present Value as a Team-Building and Decision-Making Tool

An accepted best practice in project management is establishing core teams of people representing different departments who will stay with the project from beginning to end. Although there seems to be growing acceptance of the core team as a concept, many organizations have found it difficult to develop and motivate these teams in the concrete. One way to help develop this team of people with varied backgrounds is to have them work together to make decisions regarding the project. This is a good idea in theory; in practice, however, project managers often express frustration in getting core team members to agree on a decision. Although each team member acts in a rational manner, the team itself does not act in a rational manner. What is the project manager to do?

Many organizations use net present value as a criterion for selecting projects. However, once the project is selected and funded, the expected net present value is soon forgotten as project managers focus on outcome, cost, and schedule. Project managers develop core teams to execute projects and concentrate on the outcome or project goal as a method for developing the team, developing a shared understanding, and resolving disputes. The basic idea is to have core team members concentrate on a common goal in order to develop a common view on how best to execute the project. While this is an excellent team-building technique, net present value can be used as an aid in making project decisions as well as an additional team-building tool for developing a shared understanding and resolving disputes. Not only does it build the core team, but the practice also links a project selection criterion to project decision making.

UNDERSTANDING THE PROBLEM

A first step in solving the problem is understanding the cause. Many people often assume that because the team is composed of rational people, the result will be rational behavior. This is not always the case, as was shown in Box 2.1.

To illustrate the problem, assume a core team of three people: X, Y, and Z. Each of these rational people has to make a decision among choices A, B, or C. They rank the choices in the following way:

X: A > B > C; therefore A > C.

Y: B > C > A; therefore B > A.

Z: C > A > B; therefore C > B.

Now let the three rational people vote on the choice. When we compare A with B, we find that A > B by two out of three team members, X and Z. When we compare B with C, we find that B > C by two of the three team members, X and Y. From our definition of rational behavior, we would feel that if A > B > C, then A will be preferred to C. However, when we compare A with C, we find that C is preferred to A by two of three team members, Y and Z. That is, the situation we see is A > B > C with C > A. Obviously, this team will have difficulty coming to a decision, for no matter which choice is proposed, there will always be two team members who prefer something else. The sum of rational behavior is not necessarily itself rational behavior.

BUILDING A TEAM EVEN WITH SUCH IRRATIONAL BEHAVIOR

One expedient answer to this problem is for the project manager to express an opinion and give himself a vote. For example, if the project manager were to state a preference as A > B > C, then A > B by 3/4 and B > C by 3/4, so it looks as if A is the choice. However, C > A by 2/4. This is not much better, so it might require a project manager to pull rank to break the tie between A and C, which would result in A as the winner. In this case, the team members may wince because A is the project manager’s first choice, not their first choice. This situation will probably sour any developing team spirit. This is an expedient solution but not a good team-building decision. Having the project manager jump in and take over could demoralize the team and irritate team members, and it will not help them develop problem-solving skills.

A second answer might be the political approach, which is usually distasteful to project managers. For the political approach, the project manager tries to get one person to change one of her preferences. This might be done by making some sort of deal. Perhaps the project manager can tell person Z that he will give her extra budget to switch preferences between A and C, such that Z now states A > C > B. In this case, the vote is A > B by 2/3, B > C by 2/3, and A > C by 2/3, a seeming return to rationality. But at what cost? The project manager now owes something to one of the core team members, not a good position to be in. In addition, other team members will soon find out about the deal, not a good team-building technique.

A third approach is to appeal to a higher power, a shared understanding of what the project is meant to achieve. This approach begins with the project manager’s working to understand why these people hold their preferences in the first place. In many cases, the reason for the irrational team behavior is that the individual points of view are being considered in isolation and are based on individual departmental preferences rather than a project goal. To develop a shared understanding, consider these points of view in relation to each other while indicating how the different choices will affect the net present value of the project and its outcome.

AN EXAMPLE (POSSIBLE FOURTH OPTION)

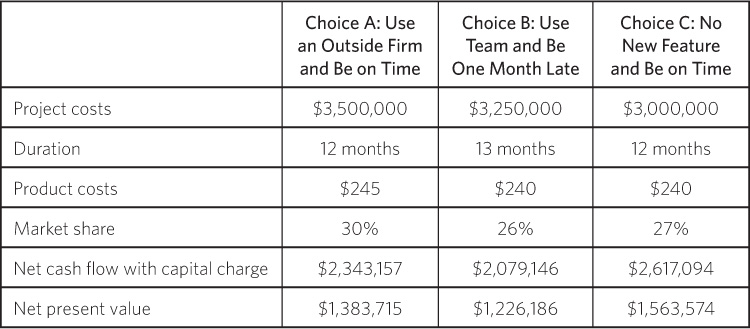

Assume a core team of three people on a $3 million project to produce a new product in twelve months. Using the team, the product will cost $240 to produce and will sell for $300 with an eventual market maturity of 20,000 units per month. Competitors will introduce similar products in twelve months. If this product matches the competition and is ready in twelve months, it should capture a 30 percent market share. The team is attempting to determine whether to add a new feature to the product it is developing that was not in the project scope. It is considering three choices:

• Choice A is to have an outside firm develop the feature for a cost of $500,000 with no delay to the project. Because there will be no delay and the product will have the new feature, it is expected to capture a 30 percent market share. Using an outside firm adds $5 to the cost of producing the product.

• Choice B is to delay project completion by one month in order for the team to add the feature. This choice means a project cost increase of $250,000 but no increase in product production costs. Since the product will be delayed one month after competitor introductions, it expects to gain only a 26 percent market share.

• Choice C is to forgo the new feature so the project proceeds according to plan with no increase in project or product costs. Without the new feature, the product expects to capture a 27 percent market share.

Now consider individual preferences for members of the core team:

X: A > B > C. The marketing manager feels that the product should contain the latest technology, so having the new feature is important. It is also important that the project not be delayed, in order to capture the most market share. Therefore, this manager prefers A over B and then C. A problem with choice A is that it adds to product production costs, but the marketing manager says, “That’s production’s problem.”

Y: B > C > A. The production manager feels that the new feature is important because competitors will most likely have this feature. However, because competitors will have the feature, there can be no increase in price to cover extra production costs. Therefore, it is important that the product be completed at minimum cost.

Z: C > A > B. The financial manager wants cash flow to start as soon as possible and believes that early cash flow will make up for any cost increases.

You might be tempted to break the decision into two parts. That is, both choice A and choice B involve adding the new feature, and these choices are the first choice of the marketing and production managers, respectively. You might be tempted to say there is a preference for adding the new feature, so the only real decision is whether to delay or not to delay—that is, the choice between A and B. Here there is a clear choice because both the marketing and financial managers prefer A to B. Therefore, it looks as if the winner is to have the outside firm develop the feature.

However, the production manager is still concerned because she believes that the increase in product cost will decrease profitability. The team agrees and may use a business systems calculator to estimate the net present value of each decision choice. Using a capital charge of 15 percent and a tax rate of 33 percent produces the net present value results in Table 4.1. Using this analysis, not adding the feature is now a clear winner.

The power of a net present value analysis is that it is able to take the three variables of project cost, product cost, and market share into consideration at one time and yield one numerical valuation. In this way, the results of the three different variables in each choice can be compared with one another, and the choice becomes clear.

Of course, there will always be arguments over the numerical values assigned to the variables, especially when one’s favorite choice does not fare well in the evaluation. For example, the preceding analysis is particularly sensitive to market share estimates. Rerunning the analysis with market share for choice B at 28% and C at 25% results in net present values of $1,474,223 and $1,310,386, respectively.

In this case, it does not take much to change the rankings such that B is now preferred and previously preferred choice C now ranks last. This type of analysis can be manipulated by the types of maneuvers described in Chapter Two. Since the choices are so closely ranked and so easily affected by market share estimates, the team needs to obtain the best market share estimates possible.

When numbers are developed that everyone believes in, people will more likely abide by the results. Computed numbers raise suspicion and cause arguments unless the basis and means for the computation are clear. Use defensible, possibly conservative numbers, and take the time to explain them and get consensus on feasibility. A danger is that arguments ensue over calculations and detract from value-added decision making. Demonstrating a range of values that produce either different or consistent outcomes illustrates influence points. The aim is to accelerate dialogue about which decision best serves the team and organization. Encourage people to explore alternative points of view or ways of thinking.

A salient feature of a net present value approach is that silo thinking, such as “increase revenue” or “decrease costs,” comes together in one formula. Both goals are important, and they interact. Some decisions affect the numerator and some the denominator; the interaction among all factors leads to optimizing the result. Use this approach not to drive people apart but to bring them together.

TABLE 4.1 Net Present Value of Three Choices

The successful complete upper manager:

![]() Defines a core team for each project

Defines a core team for each project

![]() Specifies a project or program manager for each team

Specifies a project or program manager for each team

![]() Supports the team by sponsoring a start-up meeting

Supports the team by sponsoring a start-up meeting

![]() Helps teams focus their work by prioritizing projects

Helps teams focus their work by prioritizing projects

![]() Promotes trust among team members and across core teams

Promotes trust among team members and across core teams

![]() Recognizes that core team members are not interchangeable

Recognizes that core team members are not interchangeable

![]() Rewards teamwork

Rewards teamwork

![]() Supports the efforts of cross-organizational teams to communicate and work together

Supports the efforts of cross-organizational teams to communicate and work together

![]() Uses a variety of techniques, including financial, to build core teamwork

Uses a variety of techniques, including financial, to build core teamwork