Chapter 4

Know Where You Are to Know Where You’re Going

The people who are crazy enough to think they can change the world are the ones who do.

—Steve Jobs

What are your goals with respect to sustainability? To differentiate yourself from the competition, to lead the sustainable evolution of your industry, or to entirely transform it? More than increasing your market share, are you ready to become a market leader, or even a market shaper? Firms leading the market with respect to green initiatives, transformed supply chains, and a focus on sustainable design and innovation have different goals, timelines, and restraints from those that are just starting on this path. In our work with operations executives, we have found that firms scale most effectively when they recognize where they are in their sustainability journey—specifically, whether they are in the Initiate, Develop, or Mature stage. And, by the way, in our sustainable vision for the future, all firms have the long-term goal of market-shaping transformation.

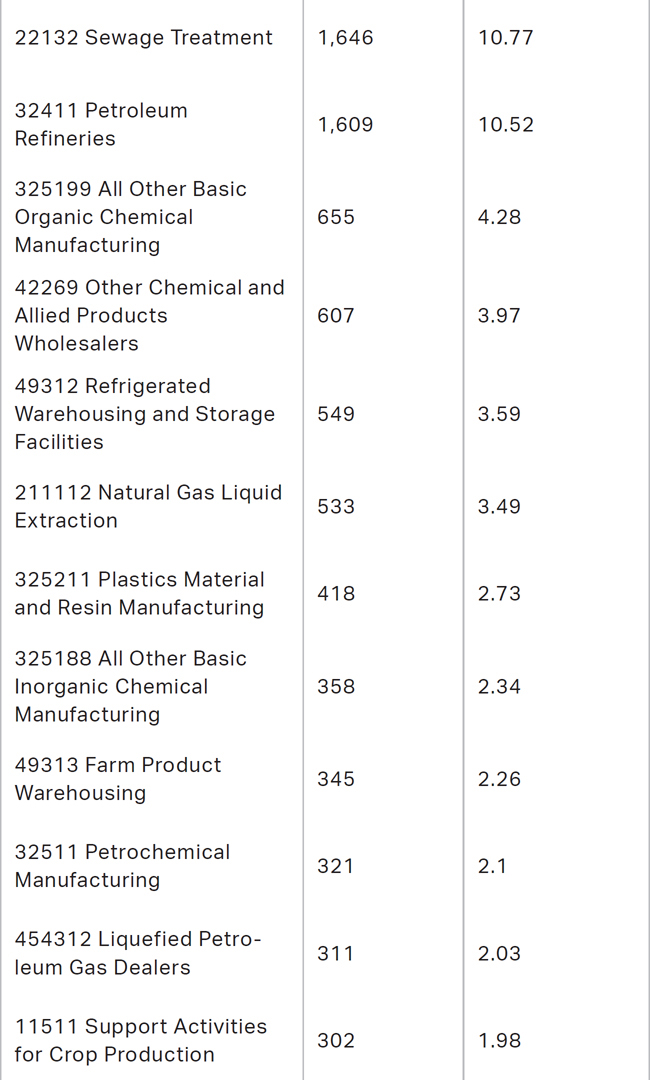

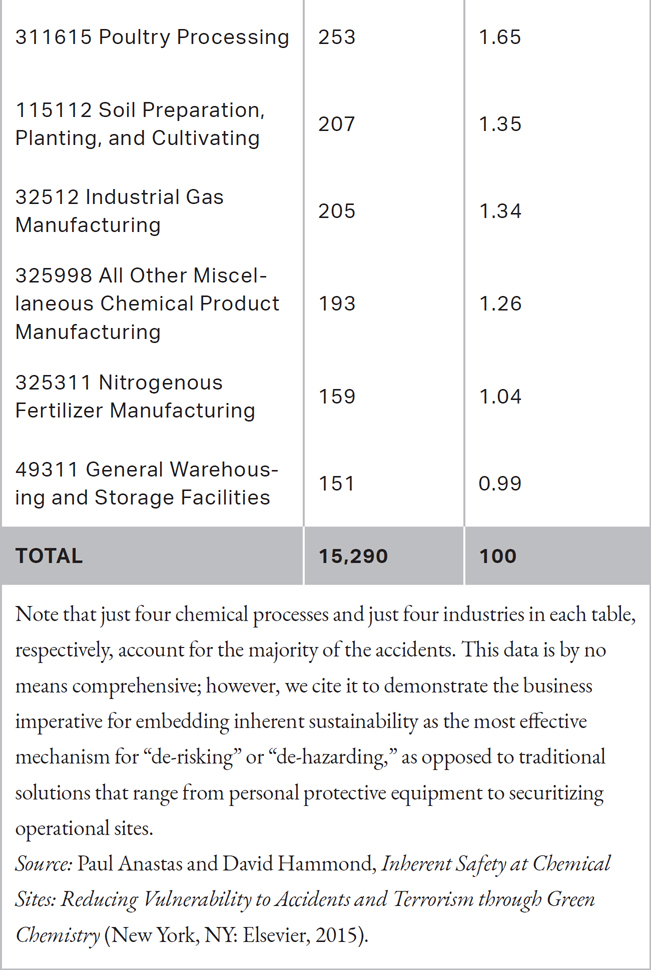

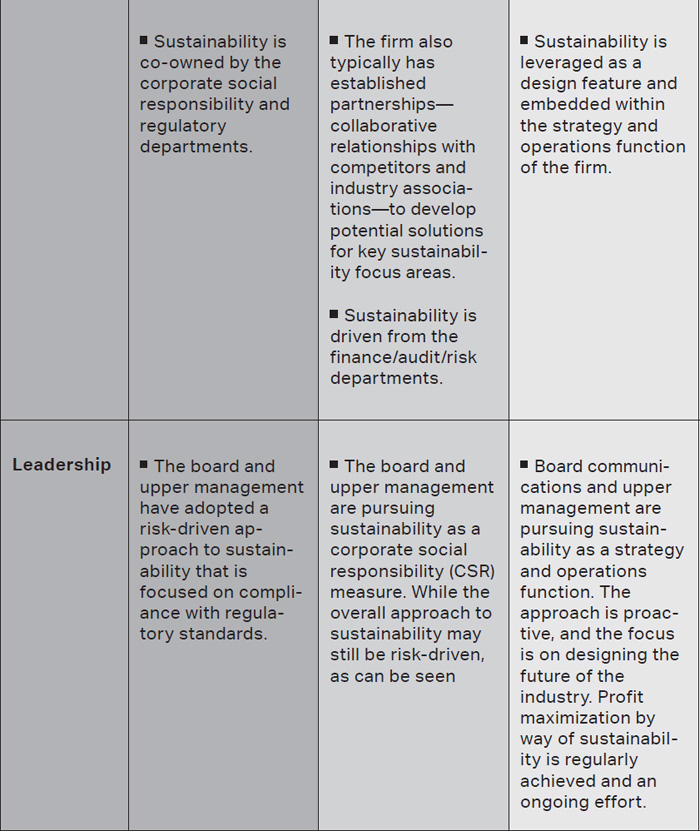

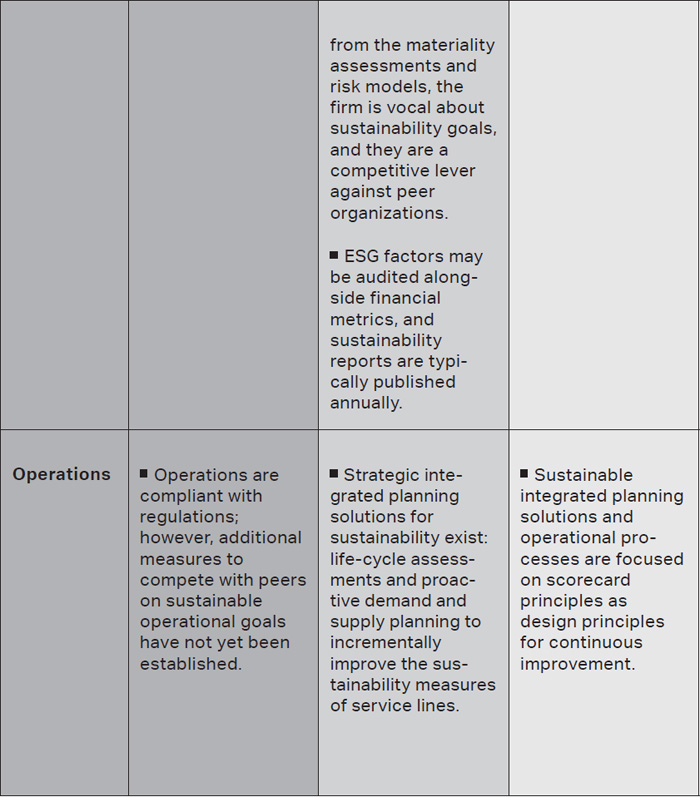

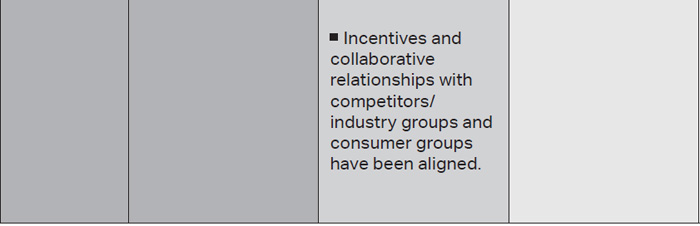

We have identified a high-level set of indicators to categorize where your firm is currently placed in its sustainability journey. This set of indicators, which we share in the table here, can help leaders identify

▪ The typical goals, scorecard outputs, and leadership strategies that firms in each stage are known for

▪ Key factors that firms in the next step of their sustainability journey typically exhibit

▪ Characteristics of the transformation journey that will help inform their road map as they progress

THE SUSTAINABILITY TRANSFORMATION MATURITY MODEL

Hazards versus Risks

Before we dive into the action plans for firms at different stages, it’s important here to discuss the difference between hazards and risks. We designed the Sustainability Scorecard to take the focus away from risk management and toward hazard management—a more action-oriented, operational imperative that can be monitored, tracked, and resolved.

Risk is expressed as a percentage, a potential outcome that can be prioritized for mitigation based on the likelihood of occurrence. Hazards, by contrast, are defined as “the potential for harm (physical or mental)” and are “associated with a condition or activity that, if left uncontrolled, can result in an injury or illness,” according to the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA). In practical terms, identifying hazards and eliminating or controlling them as early as possible will help prevent injuries and illnesses.

Hazards require action because if left uncontrolled, they will lead to harm. They need to be controlled for in a process. Reclassifying a risk as a hazard moves the actions you take into strategy and innovation, or operations and supply chain (which we’ll talk about more in the next chapter). So as we move through the action items for firms in different phases, you will see an emphasis on controlling for hazards—real, harmful events—as opposed to risks, the likelihood that harm may occur.

And . . . Action

In the next sections, you will find the steps we’ve identified for progressing a firm’s sustainability transformation based on its current stage. Although the scorecard outputs are distinct for each stage, we have intentionally divided our recommendations into two separate action plans: one for firms in the Initiate and Develop stages and one for firms in the Mature stage.

As firms in the Initiate stage are at the beginning of their journey, they will be conducting most transformation activities for the first time. For example, an Initiate firm may use the action plan we offer here to create their first hazard inventory, identify one future sustainability pilot, and initiate board and strategic communications. Meanwhile, a firm in the Develop stage may have already performed these activities and will be using the action plan to scale their sustainability pilot to additional service lines, begin to achieve board-level buy-in for greater investment into sustainability transformations, and start to create circular stakeholder engagement, and so on. A Mature stage firm may leverage the scorecard to develop strategic industry alliances with seemingly unlikely partners to address knowledge gaps in science, develop closed-loop systems for particularly challenging material and energy flows, and the like, looking to further their existing projects, leverage the scorecard into further service lines, and deepen existing partnerships that will enable problem solving for their sustainability issues.

Action Plan for Firms in the Initiate and Develop Stages

Step 1. Assess a product, service line, or process using the Sustainability Scorecard. Firms in the Initiate and Develop stages of their sustainability transformation should first complete an assessment of each of their service lines or products to uncover all the costs and hazards associated with them.

Step 2. Conduct a hazard inventory. For all metrics that do not have a score of 0 on the scorecard, create a hazard inventory list. These hazards will range from internal, such as those impacting operations, to external, including reputation and market. Let’s use electronic waste as an example. Many electronics, particularly older models, contain hazardous substances. Over 3.2 million tons of electronics enter the waste stream in the US annually, and the leaching and release of hazardous substances into the groundwater on degradation present a significant public health and toxicity hazard to consumers and populations who live near landfill disposal sites. Those who are assigned to monitor environmental hazards are likely to categorize e-waste as a substance or “material” hazard.

Step 3. Create closed-loop “unexpected” solutions based on nexus thinking. Traditional management practice involves developing a hazard response strategy, creating initiatives that address prioritized hazards, and tracking progress toward a quantitative end point. If the firm were a beverage company, for example, this could mean ensuring that as a part of water stewardship programs, blue water returned to the ground is equivalent to the groundwater extracted annually. To address the hazard of the excess e-waste, the hazard owner could decide to find an alternative material to create the device. Another option is to develop a separate plan to dispose of it or repurpose it outside the facility. However, we advise going to the next step and leveraging the nexus thinking described by Dr. Julie Zimmerman in creating closed-loop solutions.

So how can you solve the problem of this hazard instead of simply minimizing its risk? If you are redesigning a process or product, what are the solutions for your issue in the marketplace? Are there any off-the-shelf green alternatives? The problem-solving nature of creating closed-loop solutions can involve any or all of the following:

▪ Collaborating with strange bedfellows, such as a competitor or even a firm outside your sector.

▪ Upcycling component parts and leveraging recycling, parts harvesting, refurbishing and servicing pathways to achieve circularity.

▪ Innovating and incentivizing your entire supply chain!! This is actually one of the most effective levers in supply-chain transformation, as the story of Coastwide Labs will demonstrate in chapter 8.

▪ Creating sustainable drop-in replacements that do not require complete operational transformation, but can be integrated into an existing process. Drop-ins can provide several benefits from an unexpected solution without the capital and operational transformation activities that may be required to integrate a new, disruptive technology.

▪ For Develop stage firms that are looking to become market shapers or accelerate their journey into the Mature phase: funding a promising solution to accelerate the solution’s progress from lab to commercialization and then scaling. There is a common refrain, “Who does the research decides what research gets done.” Nexus thinking and creation of nexus solutions or unexpected solutions require a diversity of perspectives, competencies, and demographic factors. Taking an interdisciplinary approach, in and of itself, will alter the problem statement and therefore the solution.

Of course, there are some environmental and human health hazards for which there is not yet an immediate closed-loop solution. In those cases, firms must work to effectively manage them. The hazard response should be carried out by a designated team and carefully documented by the hazard manager, including all action items and milestones. These should be tracked and monitored by the product manager, and any significant variances from the response should be escalated to leadership.

Step 4. Pilot one transformation focused on a single product, process, or service line. Creating a single story serves to support and build a business case for future transformations across the enterprise. In chapter 8, we highlight one organization, Gundersen Health Systems, that did just that.

Step 5. Track the progress on your sustainability journey. Use the Sustainability Scorecard to track and report how your actions are leading to more sustainable processes and products. You can also use the scorecard to identify additional metrics that are of strategic and operational importance to the firm. And remember: profiting from unexpected solutions is an iterative process that requires a commitment to problem solving. As your firm continues to grow with new offerings and economic activities, we encourage you to leverage our framework and methodology to conduct iterative and real-time analysis that will enable your sustainability agendas to progress.

Action Plan for Mature Firms: Transformation

This leg of the sustainability journey is all about transformation that will yield meaningful results for the next fifty to one hundred years. While no firm is entirely sustainable, mature firms are already regularly leveraging the previous steps and are focused on market-shaping activities, rather than solely on profitability and competitive advantages.

Mature stage firms are the ones rebranding themselves and disrupting their own business models (the best way to get ahead). They are investing in initiatives and innovator hubs that are focused on placing them in a leading position in the coming fifty to one hundred years. They are looking to engage in the future now and create transformations that will, they hope, serve as standard practices for future generations. Their investments and sustainability pilots or trials may not all yield positive results, but their efforts provide unexpected and meaningful insights not just to their peers but to all firms. For these companies, their sustainability focus should be on strategy innovation, real-time assessment, and, beyond transforming themselves operationally, transforming the very markets in which they operate.

Consider the microchip, an element that finds its way into potentially every product service line at an electronics firm. In an analysis titled “The 1.7-Kilogram Microchip,” researchers at the United Nations University found that the weight of the inputs used to create a single two-gram microchip was as follows:1

Fossil fuels: 1,600 grams

Chemicals: 72 grams

Water: 32,000 grams

Gaseous inputs (mainly N2 gas): 700 grams

The weight of the materials in the production chain of a single microchip is “hundreds, if not thousands of times greater in quantity than the quantity of materials embodied in the chip itself.” In addition, microchip production is an extremely energy- and material-intensive process, and the product itself is facing unprecedented exponential growth in demand.

In an attempt to understand how market shapers faced with seemingly impossible constraints such as those described are designing a sustainable tomorrow, we turned to the executives at the global health technology firm Royal Philips N.V., often ranked by rating agencies and technical media outlets as one of the most sustainable firms in the world. That’s quite a feat, as the challenges involved in creating create circular, closed-loop systems within the electronics space is formidable.

Step 1. Make sustainability a strategic priority. Organic growth is good, but strategic growth is better. It’s surprising how many firms skip this step and create ad hoc areas for investment and growth. Strategy innovation involves a fundamental shift in mindset from hazard-level assessments to forward-looking goals that align with the Four Principles for Managing and Scaling Sustainability. Process-level metrics that directly tie into hazards develop compliance and provide some measure of security against hazard appetite assessments, but top-down metrics are for hacking growth. Evaluate your goals for the future and develop outcome measures and indicators that will serve as markers for positive growth in that direction.

At Philips, Harald Tepper, senior director of group sustainability and program lead for circular economy transformation; Bob Carelli, director of global environmental health and safety; and Trent Gross, director of upstream marketing, mentioned that the placement of sustainability as a core function within the company’s strategy and innovation practice was key to its success thus far. The team shared with us that “in most firms, it is not unusual to find sustainability addressed as a risk function or in public policy.. .. While this organizational placement may be effective, Philips has seen greater progress through the placement of this function directly in strategy and innovation, with direct oversight by the CEO. This prevents siloed thinking and niche application.” This makes sense—designing for sustainability places design constraints on innovation that can lead to unexpected transformations in operations and even in go-to-market strategies.

Step 2. Conduct real-time value assessments. Mature organizations consider their relationships with each bottom line—financial, social, and environmental—beyond the transactional. In doing so, they conduct real-time value assessments that include end-of-life considerations for their products. This is a fundamental value extension equation that we would like to elaborate on here. Let’s use packaging as an example. When it comes to the future of packaging, it is not enough for firms to upcycle discarded plastics from the ocean. The ultimate goal should be the development of closed-loop systems by

▪ Developing and utilizing biodegradable packaging (environmental and social benefits)

▪ Influencing supply-chain providers to address their own hazards and to source responsibly (financial, social, environmental benefits)

▪ Collecting discarded plastics and upcycling them into new products to prevent lost economic value (financial benefit)

▪ Developing partnerships and scaling innovative solutions to drive down their cost (financial, social, and environmental benefits)

Step 3. Conduct full-cost accounting, the extended value proposition. Full-cost accounting from procurement to end of product life (rather than to transaction) allows for an analysis of the entire value chain. This end-to-end analysis of the entire product, all the way from supply chain and procurement to end of life, allows for maximization of financial, social, and environmental assets. Market-leading firms leverage such analysis based on product and process life cycles to identify areas for value maximization, either through the addition of revenue stream opportunities or to reclaim materials that may be lost after the useful life of the product is finished. For a firm such as Philips, this has led to partnerships that are mutually beneficial to the firm and suppliers, resulting in improved workplace safety for one million workers and 25 percent of its revenue derived from circular-economy products, which include refurbished medical devices.

Step. 4. Conduct a life-cycle cost-benefit analysis. Once you have completed the full-cost accounting, a life-cycle cost-benefit analysis can be useful in identifying the biggest-impact solutions to invest in. In other words, you can address the opportunity cost of various options in this analysis.

Harald Tepper and his team elucidate Philips’s approach to real-time assessment by describing the Philips Excellence Framework. In 1891, the firm created social programs for employees—a practice that led to the creation of an environmental agenda in 1970 and sustainability transformation activities that haven’t stopped since. As the firm grew globally it inherited myriad business practices and quality systems. The Philips Excellence Framework, an internal and ever-evolving alignment tool, has been imperative in creating standardization of business processes globally. Tepper and his team tell us, “This practice, and the continual iteration of our framework as our knowledge and firm grow, allows for a common platform whereby different functions can interlink. For example, in order to operationalize sustainability transformation activities, we’ve input sustainability-related controls into existing stage-gates of our processes. This prompts leaders to fulfill the latest sustainability requirements for our products before crossing a procedural stage-gate.”

“At the end of the day,” Bob Carelli shared, “sustainability operations and supply-chain transformations are about closing material and energy loops throughout the global practice. And a dynamic framework and platform allow us to perform real-time analysis and execute on real-time decisions.”

When this real-time assessment was operationalized at Philips, it led to some unexpected approaches for value creation and reporting:

▪ Reporting. One of the metrics within the framework is for business units to report the percentage of profits that were derived from green and circular-economy products. While reusing capital equipment and reprocessed devices forms a component of the circular-economy products, much of the reporting is focused on green products that are backed by a life-cycle assessment and externally validated. Later this led to collaboration with clients to replace hardware with digital solutions where possible, to eliminate the environmental impact of net new material loops

▪ Creating new performance metrics. In our scorecard, we recommend expanding the definition of performance to include environmental and social factors. In light of the lack of national or global standards for sustainability reporting, Philips leadership has created their own standards, to align business and science-based performance targets to understand the firm’s impact against various global warming scenarios.

▪ Sharpening design requirements. Philips recognizes that its products account for 97 percent of its environmental impacts (i.e., everything in the Philips portfolio outside of business travel, sites, and logistics, for which carbon offsets, investment in renewable energy sources, and other carbon-reduction methodologies have been applied). This is important! This very acknowledgment demonstrates an action-oriented approach driven from realistic self-assessments. The firm has created an internal sustainability framework called

EcoDesign, which outlines principles and a road map to guide the company to design 100 percent of its product introductions to meet these environmental standards, as validated by a life-cycle assessment and through external validation. For Philips, the EcoDesign framework includes the following focus areas:

a. Easy to clean, sterilize, and restore aesthetic state

b. Secure and private exchange

c. Easy to assess and track performance

d. Easy to disassemble, repair, and reassemble

e. Modular design for forward and backward compatibility

f. Standard, durable element selection

g. Sustainable material selection

h. Easy to dismantle back into pure materials

To raise the bar even higher, Philips is developing green products that meet even more stringent requirements. At the end of 2020, approximately 70 percent of revenue was attributed to green products. A natural next step for any organization looking to scale green products is the effect of volume sales on the percentage-of-revenue KPI. If these products are scaled beyond their traditional counterparts, the firm can approach 100 percent of revenue from green technology sales, simply by way of continued operations for the service line. To prevent volume sales from skewing revenue metrics from green products, Philips has created an ultra-green line called Eco-Heroes, with an aspiration to have 25 percent of its revenue attributed to these products that fulfill more stringent sustainable-design criteria.

Eco-Heroes such as the Ingenia Ambition x1.5 MR Scanner fulfill the following internal criteria:

▪ Meet all EcoDesign requirements applicable to new product introductions

▪ Meet internal circular requirements

▪ Outperform the relevant benchmark (competitor, regulatory, standard) and are widely perceived as sustainable champions

▪ Have undergone a life-cycle analysis which underpins that claim

We dove deep into Philips’s real-time assessment process to demonstrate on a tactical level how market shapers leverage real-time assessments to close sustainability loops in their operations. While knowledge gaps remain for many technologically complex issues in the electronics space (e.g., cost-effective solutions for material separation and recovery with benign chemicals, safe degradation and energy-efficient material recovery for rare-earth minerals), more research will eventually provide unexpected, breakthrough solutions for 100 percent sustainable products in the electronics space in particular. However, by understanding how Mature stage firms conduct and leverage real-time self-assessments, firms can prepare themselves to integrate these breakthrough solutions once they are commercially viable.

Step 5. Draw bigger boundaries. This is where you get transformational. When optimizing a sustainable solution, consider the current design of your supply chains and products. Is there a better way? Are there opportunities for revenue with additional unexpected solutions and further process redesign?

As an example of drawing bigger boundaries, Philips executives became aware that there was no formal waste recovery process for their healthcare technology, particularly in their Africa market. This lack of a recovery process had resulted in old products being incinerated or dumped in landfills or other environmental grave-sites. To address this problem, the firm created a public-private partnership with the United Nations Environmental Program to develop collection bases throughout key geographies in Nigeria. This producer responsibility partnership, while no longer led by Philips, is scaling across Africa to create an organized network for collection bases.

Circular Stakeholder Management: Culture Transformation

Change only happens when you have enough people in influential positions on board. It is important that your priorities and related metrics tie into stakeholder imperatives and actions, as stakeholder championship will be key. Thus when you are first embarking on your sustainability journey, it is important to consider the following questions:

▪ Who needs to be engaged? What is the composition of your entire stakeholder ecosystem, and how will each role be engaged to create a “circular” communication strategy? In our experience, a good corporate communications strategy for sustainability must be circular, just like the circular changes in the economy that you are looking to drive. Therefore, communications should focus on internal marketing efforts, external communications that boldly proclaim organizational goals, and educational efforts that enable business development and consumer awareness.

▪ External. This category includes supply-chain vendors, reporting agencies, strategic communications agencies, trade associations, and other industry bodies. At Philips, partnerships with external stakeholders—even competitors and firms outside the electronics space—have led to solutions that have optimized the recovery of products at the end of their life. Harald Tepper and Bob Carelli emphasize the importance of building a voice with coalitions. Coalitions can address industry-level barriers and result in large-scale changes that extend beyond the firm. For market shapers looking to establish best practices for the next fifty to one hundred years, creating industry-wide changes in partnership with competitors, industry groups, and supply chain vendors ensures continuous and ongoing pathways for collaboration.

▪ Internal. This group can encompass board members, executives, operational leaders, managers, and staff across the firm. Within this group, ensure the presence of sustainability sponsors to oversee successful completion of the transformation. Many firms have sustainability champions and initiatives to empower their own employees. However, such efforts can ultimately remain ineffective if they are not directly aligned with transformation efforts that drive revenue.

The Philips Sustainability Ambassador program is designed to scale environmental sustainability through the education of employees in an organization of more than eighty-one thousand people; it will focus on product stewardship and is aligned with external think tanks to close the loop on leading practices and industry application. At Philips, executives highlight that operationally, this has meant “trying to bring a high degree of clarity of vision to the middle layer of the organization.” The key, Harald and his team point out, is to identify change agents throughout the organization.

Transformation efforts in sustainability rely heavily on the managers that enable day-to-day activities through their process-driven approach. This layer is where transformation efforts can get stuck, as processes and the people who manage them create embedded routines and automated solutions. Incentivizing the managers who form the middle layer of the organizational chart across all business functions is where strategy and innovation teams can play a broker role and create flexibility. This layer can be incentivized through formalized programs through which stewardship, transformation, and profitability are embedded in business processes.

From the standpoint of Board communication, we recommend creating a reporting structure for strategy and innovation such that this function has direct oversight by a CEO. This is important. For mature firms, sustainability is embedded in strategy, which receives oversight by the CEO on all the determinants of long-term value creation. Hence placing this in the direct purview of the CEO by way of strategy is important. It is when sustainability is placed under the purview of marketing, public policy, or any other department that the impact can be diminished. While these departments are important to overall firm activities, they are unable to scale sustainability holistically across a firm in the same manner that a CEO-led strategic agenda is able to effectively achieve this. At Philips, this CEO-led reporting structure is leveraged and creates an effective two-way communication related to all matters in the ESG space.

▪ Customers. Although customers are traditionally external stakeholders, we have called out this population separately to indicate a shift in the management approach for this group. In sustainability, we recommend seeing customers as partners rather than purely as users of a product. At Philips, this has led to the cocreation of unexpected solutions, such as an open conversation with Philips’s suppliers to reinforce the firm’s requirements for safer inputs. It turns out that suppliers are eager to satisfy consumers and find the formulation that will address consumer requirements. Harald and Bob advise, “When you ask the front-runners to communicate the change, you make yourself future proof.”

▪ Are all stakeholders ready to iterate? Not all problems have a commercialized solution at the present time. Additional research may be required to close knowledge gaps, and collaborating with strange bedfellows might be required! Leaders who recognize that there is no end point in the journey are better able to manage expectations, adapt to new solutions, and implement them. Todd Cort, professor of sustainability at Yale University, recommends early communication of any potential risks, followed by the creation of an ongoing forum for continuous information sharing. The Sustainability Scorecard does not have a quantitative endpoint or quantitative target, and does not recommend creating benchmark values based on current industry best practices for any of its metrics. That’s because sustainability is an evolving journey. All stakeholders must understand that.

What’s Your End Goal?

Is your goal to create “less bad” solutions that fulfill short-term goals? To merely surpass the competition? If so, chances are that you won’t experience the full spectrum of benefits that can be attained by way of sustainability transformations. You’re selling yourself and your firm short.

Schools of thought around consumerism point out that materials and material products are not really consumed. The only thing consumed is their utility. Take Ford Motor Company. Sustainability firms in the automotive industry have forced Ford not only to add electric vehicles to its roster but to rebrand itself from an automotive firm to a mobility company. Its transformation is in anticipation of the big changes coming in how humans travel, the reduction of car purchases, and the use of autonomous vehicles and hybrid traveling models that are sustainable and more efficient. While this has led to the selling of utilization (for example, the car ride versus the car), Ford can take a larger stake in this market by creating closed-loop systems that maintain overall ownership of the product.

So how can you, like Ford, innovate your unsustainable product out of existence while continuing to sell its utility via a closed-loop system? Remember, inherently sustainable products not only rival traditionally manufactured products in performance but also provide greater value by way of function and service. Now that’s a real, transformational end goal. And it starts with good design.