Chapter 6

Step 4: Choose Systemic Solutions, Not Quick Fixes

![]()

We are conditioned to see life as a series of events, and for every event, we think there is one obvious cause…. Focusing on events leads to “event” explanations…. They distract us from seeing the longer-term patterns of change that lie behind the events and from understanding the causes of those patterns.

As we've seen, because managers tend to make decisions on the basis of ideology, anecdotal examples, or past history, their opinions of what is broken and why it's broken are often wrong. And this is a big part of the explanation for why so many efforts to make things better end up failing: They don't address what is truly wrong within the business. How can people in organizations learn to distinguish between solutions that will make a difference and those that will fail? To answer this question (as well as how to identify new fads that are likely to be duds) is to really understand what's causing the problem.

Using Root Cause Analysis to Find Solutions

![]()

Many of the truths we cling to depend greatly on our point of view.

![]()

Behind every performance gap there is a root cause—which almost always is made up of multiple causes rather than just one culprit. It is important to recognize that there are multiple causes, because part of the reason managers jump from one magic bullet to the next is a wrongheaded belief that the performance gap is a result of only one factor—and thus one initiative or program will provide the magic fix! So it helps to start by realistically admitting that any performance issue is probably going to require several solutions that address systemic issues.

Cause analysis itself (which we looked at in detail in chapter 5) requires a little patience, some serious thought, and an effort to be objective. But most organizational performance issues can be analyzed to uncover their root causes. Once managers are aware of these causes, it's tempting to craft answers to improve performance that are rooted in the flavor of the month or guesswork. Too many managers have “answers” (in the form of their pet solutions) in search of a problem. But that's the wrong approach. The root cause needs to drive what solutions to use. This is a challenge for many managers, because even after the root cause of a performance gap has been identified, managers will tend to fall back on the pet responses that worked for their previous companies in different circumstances.

Types of Root Causes

![]()

If you find a good solution and become attached to it, the solution may become your next problem.

![]()

Causes of performance gaps fall into six categories (Sanders and Thiagarajan 2001):

• Resources—the tools, supplies, tangible assets, and materials necessary to do the work. Examples of how this contributes to performance deficiencies include computers that can't run the software installed on them, inadequate tools, and unrealistic deadlines.

• Structure and process—the way that work is supposed to be done and how the organization functions. Examples of how this contributes to performance issues include inadequate job descriptions, a work process that has redundant steps, and people who have to work against the organization to do their job.

• Information—critical data that potential high performers need to do their jobs correctly. Some examples of how this contributes to performance breakdowns include important details that don't get shared with performers, such as work priorities, customer feedback, input from management, and details about a task.

• Knowledge and skills—the ability of employees to do the work. This causes performance gaps when employees are asked to do things they aren't trained to do or get critical tasks out of sequence, or when the organization confuses knowledge about a task with the ability to actually do it.

• Motivation—the attitudes of employees and internal and external incentives. Motivational causes of performance issues include instances where doing the job results in punishment (such as hard workers who are just given more work); fear of failure, which may lead to an unwillingness to take risks or ask for clarification; and a discouraging job.

• Wellness—the mental and physical health of employees. Performance gaps can be the result of substance abuse, emotionally troubled people going through personal traumas such as a divorce or a death in the family, a lack of sleep, or employees who are tired after a long shift.

![]()

We trained hard, but every time we were beginning to form up into teams, we would be reorganized. I was to learn later in life that we tend to meet any new situation by reorganizing and a wonderful method it can be for creating the illusion of progress while producing inefficiency and demoralization.

![]()

Some additional explanation of several of these categories is useful. Consider the category of structure and process. Managers may spend much time looking for the best organizational structure or redoing processes to build in efficiency. These efforts are noble, and they are often reflected in organizational restructuring initiatives. But despite these actions, most organizational processes are substantially dysfunctional.

Why are these organizational processes dysfunctional? First of all, most organizational redesigns do not occur from a systems perspective. Thus, an organizational chart is reworked but little thought is given to process or workforce issues. Or a process is reworked to shorten it and improve efficiency—but organizational rules aren't changed to reflect the new process, others seek to safeguard their small part of the process, or the new way doesn't reflect the performers' capabilities. A systems perspective allows insight into the dynamics within the organization. The concept of system archetypes provides an understanding of how different organizations can share similar behaviors while also identifying leverage points that allow for successful changes.

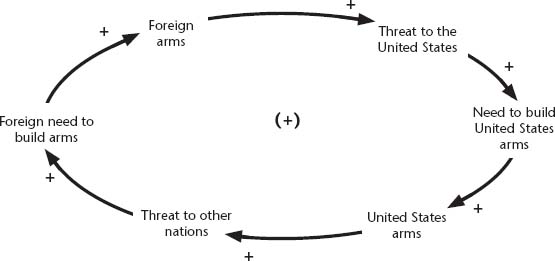

Figure 6–1 gives a sample systems perspective on an arms race. It shows how despite the detail differences (in the countries involves or the nature of the weapons), the dynamics of the system that produce an arms race remain relatively similar. This is a form of “systems archetype,” a term for system behaviors or dynamics that tend to remain true regardless of different systems.

Here's another example of a systems perspective. The managers of the former department store Woodward & Lothrop once revised their buying process to improve efficiency and save money. A process that involved buyers in the field, assistant buyers in the home office (who kept track of orders and available funds and provided support for the buyers), and administrative assistants (who did word processing, filing, and phone coverage) was reworked to eliminate the assistant buyers, resulting in fewer people, a more direct process with fewer hands touching each work product (with theoretically less potential for error), and lower personnel expenses.

Figure 6–1. Sample of a Systems Perspective: A System's View of the Arms Race

On paper, this was a simple yet elegant redesign. In reality, it was a disaster. The new process demanded skills of the administrative assistants that they did not have and required them to work hours they didn't sign up for (since the buyers were often overseas, and phone calls involved substantial time zone differences). The restructuring led to slower work cycles with more mistakes and increased turnover among the buyers (who felt less supported) and the administrative assistants (who weren't capable of doing the work and also didn't want to do that kind of job). None of the anticipated efficiencies in cost savings and shorter cycle times were achieved. Instead, personnel expenses went up, errors increased, and the buying process ended up taking longer.

In addition, as an organization's processes become intermingled with those of its partners (through activities such as outsourcing training and human resources functions, lean manufacturing, and using contractors for functions that aren't core competencies), these processes become extended. The more players there are in a process, especially when it becomes extended, the greater the likelihood that people will work at cross-purposes against each other. This is not because some owners of process components are saboteurs; it's because their myopic focus on their small role tends to make them lose sight of the big picture.

![]()

Simple solutions to complex problems are inherently attractive and almost always wrong.

![]()

Thus, travel offices within companies often become obstacles to arranging business trips for employees rather than people who make that work easier. Contracting offices often consist of people who interpret their job as placing additional requirements on those managers who would purchase outside services rather than making it easier to hire outside resources. When employees feel that they have to engage in heroic measures to get work done or that they have to work against the system to do their job, this is a clear sign that the extended process has become dysfunctional.

The Issue of Motivation

![]()

I'm slowly becoming a convert to the principle that you can't motivate people to do things, you can only demotivate them. The primary job of the manager is not to empower but to remove obstacles.

![]()

Consider the issue of motivation as it relates to performance. Managers typically speak of motivation in employees as if workers are either motivated or unmotivated—an either/or situation. The reality is far more complex. All humans are motivated—they just may not be motivated by the factors that management wants them to be motivated by. And motivation is not as simplistic as the dichotomy that people are either or aren't motivated. It's really more a question of identifying each person's motivational factors.

Also, there is usually a mixture of issues in play that serve both as motivators and demotivators. Look at your own experience. Very early in your professional career, you probably had a job where you worked hard and got all your work done early. Did you get to go home early that day? What probably happened is that you were just given more work. And the lesson you learned that day was: Work hard but not too hard—or always leave something to do at the end of the day, so your manager won't give you somebody else's work to do. This is not a case of your being unmotivated but a factor of your both wanting to do a good job (work hard and fast) yet also wanting fairness and equity (and feeling that it's wrong for you to work hard while someone who's lazy gets off as you do their job).

In addition, some other cause often precedes motivation. A demotivated employee rarely starts out work demotivated. For example, most new police officers are energized when they graduate from the police academy—they are ready to go out, change the world, and make it a safer place. But many veteran officers later experience burnout—what some might call a lack of motivation—which is manifested in a belief that working hard will make no difference. Generally, what precedes this burnout are a host of other causes, such as equipment shortages (not being able to get body armor or an inadequate supply of rape kits), a perception that promotion processes are unfair (in which promotion to sergeant is typically driven by exam scores rather than the trust of fellow officers), and a lack of information about what is going on (feeling left out or uninformed on internal departmental policies). And thus a highly motivated officer eventually turns into one who stops caring about the job.

In this example, the cause of the performance gap might be a motivational issue, but something else preceded that cause in the first place. Most organizations do an abysmal job at motivation because they fail to understand the complexity at work here.

Achieving Better Performance in Varied Fields Using Evidence-Based Analysis

![]()

Data can tell you a lot. Opinions without data are severely risky.

![]()

The concept of doing cause analysis to improve performance and enhance execution applies to practically every field. Take the example of military field medicine. In U.S. military history, the proportion of fatalities among military casualties has gone from a high of 40 percent (in the Revolutionary War) to a low of 24 percent (Vietnam and Iraq–Desert Storm). This lowered fatality rate has occurred despite the fact that in each conflict, weapons have become much more lethal and the ability to deliver mortal wounds to combatants has become much greater. However, from the 1960s and 1970s in Vietnam to the 1990s and 2000s, the mortality rate has remained constant, which seems to imply that the ability of medical advances to improve survival chances has more recently been offset by the increased lethality of weaponry.

The conflict in Afghanistan and the second Iraq conflict, Operation Iraqi Freedom, have now gone on long enough and involved sufficient casualties that it's possible to make comparisons with other major U.S. wars. And the fatality rate among U.S. casualties for these two conflicts is at 10 percent of all casualties. But for the war in Afghanistan, quick medical care and rapid evacuation face major obstacles, while the casualties in the Iraq war often result from improvised explosive devices with a higher capacity for mortality than gunshot or shrapnel wounds. Thus the mortality rates for both wars should be higher, not lower, for these conflicts.

A cursory glance at the 10 percent mortality rate might lead an uninformed observer to conclude that doctors are getting better or troops are becoming luckier, or perhaps the nature of the conflict is the cause. But the real reason for this lower mortality rate is that intelligent performance analysis by the military medical services led to organizational changes in how they provide emergency medical care in the field. These changes were driven by data (not ideology, anecdotes, or opinions), involved a study of the military field medicine delivery system, and especially relied on cause analysis to generate insights that led to major changes in field medical care.

The U.S. military has assiduously studied factors that influence the survival of those wounded in combat. Proximity to medical care has proven to be a performance driver—the sooner a wounded soldier can receive surgical care, the greater the chance of survival. As a result, from Korea to Vietnam, the U.S. military made great strides in quickly getting wounded soldiers from the field of battle to field hospitals where emergency care could be delivered. In Vietnam, only 2.6 percent of those wounded who made it to a surgical hospital died. But with an overall mortality rate of 24 percent, this indicated that despite efforts at speed, most deaths occurred before a trained doctor could intervene.

Before the Afghanistan war and Operation Iraqi Freedom, the U.S. military made fundamental changes in its approach to delivering field medical services. Recognizing that speed is a lifesaver when it comes to casualties, the U.S. Army Medical Corps has created what are called Forward Surgical Teams (FSTs), which consist of surgeons and support staff with the facilities capable of doing emergency lifesaving surgery on critically wounded individuals. But unlike the emergency medical care available during the Korean and Vietnam conflicts (which often consisted of field hospitals), the FSTs typically travel in vehicles right behind the frontline troops or even on the frontlines.

Typically, an FST consists of no more than 20 total personnel in six Humvees (the modern equivalent of a Jeep), so that they operate much closer to the fighting. Data has shown that this results in significantly faster cycle time from the incidence of a wound to the start of emergency surgery. After being stabilized by the FST, the wounded are then passed on to Combat Support Hospitals, which provide more detailed care. Then casualties that require additional medical support are sent to the United States. In Vietnam, it was an average of 45 days from battlefield to the time that critically wounded personnel returned to the United States, but in Iraq and Afghanistan, the average is now less than 4 days (Gawande 2004).

In the past, this ability to actually put surgical teams either on the frontlines or immediately behind them was limited because so much equipment and material were needed to provide care for wounded soldiers for 24 to 48 hours after surgery. Doctors typically tend to take ownership of patients and want to care for them long enough to be sure they have been stabilized and are improving. But FSTs are so mobile because they are not equipped to handle more than 6 hours of postoperative care for a patient. For a physician, this is a significant and somewhat difficult change—it means giving up patients sooner. However, the military recognized that a faster time to surgery wouldn't be possible unless surgical teams were closer to the fighting, and that wouldn't be possible unless doctors were willing to radically change the way they viewed their responsibility. According to the surgeon Atul Gawande (2004, 60), “It is a system that took some getting used to. Surgeons at every level initially tended to hold on to their patients either believing that they could provide definitive care themselves or not trusting that the next level could do so.”

The evolution and use of FSTs by the U.S. military shows how evidence-based analysis at a systems level can produce significant improvements in performance or execution. If the military had gone with biases or ideologies, it would have made changes in the opposite direction from FSTs, by allowing patients to remain longer with doctors. But for FSTs to work, conceptually and in practice, the military had to create lean units without the ability to provide sustained care and thus had to move away from the medical professional's preference for owning the patient. Instead, an objective cause analysis identified ways to boost performance and get better results—and in this case, better results means lives saved.

Multiple Causes Need Multiple Solutions

![]()

The solutions all are simple—after you have arrived at them. But they're simple only when you know already what they are.

![]()

As mentioned above, a cause analysis of any performance gap will usually identify numerous root causes. This is because performance in an organization is influenced by many factors—and thus, because there are rarely simplistic answers, multiple solutions are usually necessary. Also, because producing change within an organization requires a systemic approach, the organization will need to make changes on a variety of levels. What in hindsight may appear simple is usually deceptive in appearance.

Remember, simplistic approaches usually ignore the reality of the system. Changing a process to make it more efficient may also require changes in job assignments and position descriptions, new skills for employees, altering organizational policies, adjusting appraisal and benefits, and aligning support processes. There is no such thing as a simple change within an organization. This also explains why so many fads and simplistic solutions don't work. Even if the initiative had a chance of succeeding, managers typically fail to view the organization as a system. The initiative is typically adopted only from one perspective rather than taking organizational, process, and performer perspectives.

![]()

Off-the-rack solutions, like bargain basement dresses, never fit anyone.

![]()

This also explains why too many organizations make the mistake of borrowing solutions from other companies only to see them fail. It's not that the idea of comparative benchmarking is a bad one—tremendous insights can be gained by looking at other businesses. Indeed, very different businesses in very different fields may share similar system dynamics. For instance, the principle of system archetypes uses an understanding of dynamics to explain how different system can produces particular behaviors or results. Looking at the dynamics of an arms race between two countries (see figure 6–1 above) can also provide understanding for how a husband and wife may escalate an argument or of the forces behind a price war between retailers. However, the tendency is for organizations to copy gimmicks or techniques and ignore the culture or principles behind the techniques.

Consider the case discussed earlier of a top-performing Best Buy store manager, Ralph Gonzalez, who had energized his workforce and built a focus on key results. “Most companies would take a best practice like Ralph's whistle and say ‘that's a great form of recognition. Let's give out whistles in every store.’ Best Buy did something much smarter: it extracted and spread the core lesson from Ralph's best practice rather than institutionalizing the practice itself” (LaBarre 2001). Unfortunately, Best Buy's approach isn't common. Companies look to other organizations for ideas but implement those ideas without a deeper understanding of why they succeed or what they need to change in their own business to make them work.

According to Pfeffer and Sutton (2006, 7),

People copy the most visible, obvious and frequently least important practices. Southwest's success is based on its culture and management philosophy, the priority it places on its employees (Southwest did not lay off one person following the September 11 meltdown in the aviation industry), not on how it dresses its gate agents and flight attendants, which planes it flies, or how it schedules flights. Similarly, the secret to Toyota's success is not a set of techniques but its philosophy—the mindset of total quality management and continuous improvement it has embraced—and the company's relationship with workers that has enabled it to tap their deep knowledge. As a wise executive in one of our classes said about imitating others, “We have been benchmarking the wrong things. Instead of copying what others do, we ought to copy how they think.”

Managers need to be especially careful about how they conduct external or comparative benchmarking and what lessons the company purports to have learned from these exercises.

![]()

Building an effective organization is ultimately a matter of meshing the different subcultures by encouraging the evolution of common goals, common language, and common procedures for solving problems.

![]()

Part of the difficulty of borrowing ideas from other businesses is the reality of organizational culture. Executives take processes or methods from one company and try to transplant them to another while failing to realize that each firm's predominant organizational culture has a great impact on whether or not that initiative flourishes or dies. To a great extent, initiatives succeed because they fit and are supported by the culture in which they exist.

Systems Require a Systemic Approach

The consultant Geary Rummler developed an approach in the 1960s that emphasized the importance of a systems approach in both understanding performance and improving it (Rummler and Brache 1995). Rummler argued that to improve performance, the organization had to be viewed as a system in which many apparently independent parts were actually interdependent. This effectively means that performance needs to be analyzed using a systems perspective and that potential solutions need to occur within the system and be implemented using a systems perspective.

Rummler's approach analyzes the system at three basic levels—organization, process, and performer—each of which has several elements:

• Organization: culture, mission, vision, internal policies, organizational chart and hierarchy, rewards, goals, operating strategy.

• Process: how the task or work in question combines with others to form a process, work flow, job design, necessary inputs, the performance management process, supporting processes.

• Performer: individual employee goals, knowledge and skills, demographics of the workforce, number of personnel doing particular work, support tools.

To show how this works, suppose an organization wanted to provide training for frontline employees so that they'd do a better job making decisions on their own (rather than always consulting supervisors). The rationale for the training is to speed up work cycles and encourage initiative by the employees. This sounds fine in theory. But analysis at a performer level may show that many of the frontline employees don't aspire to be quasi-managers and resist the responsibility for making decisions. Examination at a process level may show that even if frontline performers made decisions, their immediate supervisors would have the ability to overrule or reverse those decisions.

This process element would effectively prevent any value gained from the training because workers, recognizing that any action could be reversed, would still be reluctant to take initiative. Instead, many employees might assume that it would save time to just consult with their supervisors before taking any action rather than taking initiative and having managers demand justification and tinker with the initial action. From an organizational level, company policy may limit the access to information that frontline staffers are given (thus making it difficult for them to make good decisions without consulting supervisors).

This lack of access to information (such as personnel records or customer history) may lead to inadequate decisions that managers end up overruling. And when this happens often enough, it discourages initiative because employees perceive that anything they do will be overturned by management anyway. In some circumstances, it could even be counterproductive. For instance, if the culture is strong enough to discourage initiative, then training people to take action would either breed cynicism or perhaps lead employees to start believing they're being set up to fail—by contradictorily being told to act without consulting management while the culture says acting without consultation is wrong.

The point is not that these issues can't be overcome. But it should be very clear that a simple training course isn't a systemic response and therefore will likely be overwhelmed by the organization's system, which will encourage people to return to the old way of doing things and not use the new skills learned in training. From the standpoint of your own organization, you should probably also be able to see that it's now clear that training as a sole solution to a problem is almost always doomed to fail—because it is not likely to address the system's elements and the range of interdependent factors that influence performance. It's critical to take a systems view of any issues so that solutions don't end up as merely Band-Aids when surgery was called for.

Organizational Culture Matters

![]()

Organizational culture eats strategy.

![]()

Organizational culture has a tremendous impact on the success or failure of any initiative. Culture can support execution or promote practices that discourage performance. Most CEOs pay lip service to the importance of an organization's culture (LaBarre 2001). And yet organizational cultural is poorly understood. According to Marcus Buckingham, “You won't find a CEO who doesn't talk about a powerful culture as a source of competitive advantage. At the same time, you'd be hard-pressed to find a CEO who has much of a clue about the strength of that culture” (quoted by LaBarre 2001).

What is organizational culture? Although it's often referred to as if it was a tangible, single item, organizational culture is really a metaphor that can be used to explain corporate life in terms of practices, perceptions, values, relationships, and identities. More specifically, there is no such thing as a single culture within an organization—rather, what people refer to as organizational culture is something that differs between your IT department and your marketing department. The field offices feel different than headquarters. So to the extent that there is an organizational culture, it's really a multitude of cultures within any one organization. Thus, executives who think they're taking organizational culture into account when making changes will still fail because they do not realize that there are actually dozens or even hundreds of different cultures within the organization.

In fact, organizational culture is really shorthand to refer to several different factors of corporate life:

• Values—which includes group norms, members' aspirations and hopes, who sets or influences those corporate values, differences between real versus stated values, and situational elements (or the degree to which values change depending upon the circumstances).

• Behavior—nonverbal behavior, standard greetings or patterns of interaction, what topics are considered “undiscussable,” how people deal with conflict, what's appropriate for celebrating, and the way that it's accepted that people do things in the business.

• Language—jargon common in the business, metaphors that are imbedded in the firm, hidden or implied messages, and perception.

• Power—what traits are most respected or feared, how people get and keep clout in the organization, the influence of peer pressure, and formal versus informal authority issues.

• Symbolism—organizational heroes or stories, objects that are symbolic within the company, and events or actions with special meaning for the employees.

• Work style—how decisions get made, what constitutes clutter, the degree of orderliness expected, typical work pace, reaction to crises, time orientation, and the degree of formality and reliance on rules at work.

![]()

Culture hides more than it reveals and strangely enough what it hides, it hides most effectively from it's own participants.

![]()

All these factors contribute to what is referred to as organizational culture. These factors shape just how execution-friendly the organization will be and how likely a new initiative is to be embraced or rejected. Because these factors are informal and so embedded within the firm that people often become unconscious of them, they're very easy to overlook when trying to improve performance. And because these factors vary from unit to unit, it's very easy for management to misdiagnose what challenges any initiative will face. Finally, the ability to directly shape most of these organizational habits is limited at best. As the consultant James Pepitone (2000, 133) notes, “Organizational culture determines the success or failure of all interventions yet there is no intervention that directly changes organizational culture.” What this means is that these organizational habits or factors shape managers' ability to change, yet these habits or factors can be changed only indirectly at best. As a result, this thing called organizational culture is difficult to get a hold of from a management perspective. And a failure to both understand these organizational habits and account for them will result in initiatives that are temporary Band-Aids instead of real solutions.

Performance Solution Notebook

![]()

How organizations have dealt with health-care-acquired infections (HAIs) is a good illustration of the difference between a and-Aid approach versus a real solution. Most health care facilities have attempted some sort of action to deal with HAIs, especially MRSA (methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus). Yet too many of them have been ineffective. In some cases (as mentioned in earlier chapters), the failures have had to do with facilities focusing on the wrong causes (or not having even done a cause analysis). specially with health care, there is a tendency to underestimate the importance of the system on performance. As Donald Goldman (2007, 2) notes, “Patient-safety experts stress that complex, error-prone systems are at the root of most mistakes in health care. Archaic, poorly designed systems often undermine the best efforts of well-intentioned, highly motivated clinicians and health care personnel to provide safe care.”

In many cases, HAI initiatives have not been well thought out or have taken approaches that aren't realistic. This is especially true for hand hygiene programs, which initially would appear to be simple to implement. However, most hand-washing initiatives have resulted in low levels of compliance (Gawande 2007). art of this is a function of failing to understand why health care professionals don't wash their hands before every patient encounter and the numerous barriers to getting high levels of compliance. Because the primary solution (sanitizing hands before and after every patient contact) seems so easy, the assumption many health care organizations make is that the solution to HAIs is therefore simple—just require hand washing.

But the problem with such a simplistic approach is that health care providers find themselves so busy and preoccupied with issues that are important in the moment that compliance with hand-washing protocols is typically dismal (Gawande 2007). Health care providers often find themselves having to wash their hands hundreds of times in an typical day. Besides the tremendous irritation and dermatological problems caused by such prodigious washing, there are other problems (Brennan 2006). Using traditional washing methods and avoiding a perfunctory approach, a doctor could spend more than an hour each day just sanitizing his or her hands. Even with more recent alcohol-based washes, it's still a time-consuming process that harried professionals can easily miss. And sanitizing stations aren't always conveniently located, given the frequency of patient contact. and-Aid level approaches fail to take these realities into account.

Health care facilities that have successfully reduced HAIs have taken a sophisticated approach to this problem rather than sought out simplistic mandates. or instance, the rate of MRSA infections was reduced by more than percent in one Pittsburgh Regional Healthcare Initiative (RHI) facility. This approach was one that quality engineers at Toyota would have identified with and also exemplified many of the practices identified in this book to improve performance. “The approach used floor-based consulting to standardize work flow protocols, identify problems as they occur, apply countermeasures to prevent their recurrence, and improve communication to spread the countermeasures rapidly throughout the unit” (Guadagnino 2006, 8). This success was even more impressive because it happened at the same time that the unit increased the number of surgical enhanced care beds by 50 percent.

The PRHI obviously did not use a and-Aid approach. It recognized the need to analyze the problem from a systems perspective, make the program a priority and establish accountability, analyze performance problems in a way that allowed for real-time improvement, and adapt solutions to the nature of the organization. This approach wasn't rocket science, but it also showed that taking the time to analyze what was going on and then develop a sophisticated initiative would pay off.

Hitting the Mark

![]()

For organizations that want to get results, these are critical lessons:

• Be objective in evaluating performance issues. Most people fail to recognize that their perspective is always subjective, so special effort is necessary for an honest assessment. An objective, systematic analysis doesn't have to be time consuming, but it does mean avoiding a rush to judgment.

• It's not enough to identify a performance gap; you must determine its causes. This is often where perceptual bias is a factor, because executives frequently default to familiar approaches (such as training or bonuses) as excuses for what is wrong and ways to fix it.

• There is almost never just one cause for any performance problem. Usually, there are multiple factors. All of them don't have to be solved, but rarely is one program or intervention going to provide much progress on a problem. Any analysis that reduces a problem to one cause or factor is probably simplistic.

• Look at problems and solutions systemically. An effort to fix something that doesn't address the system—at the organization, process, and performer levels—is almost certainly going to fail, either immediately or in the long term. An initiative that doesn't take a systems approach is probably simplistic and therefore likely to fail.

• Organizational culture is a critical factor for both analyzing problems and developing solutions. Executives who successfully borrow ideas from other companies also look for compatible cultures. And they're not quick to pull out simple solutions or apparently limited programs; they realize there are probably contributions to program success from the culture of the company they're benchmarking.

Failure to get to the cause of the performance gap is a sure way to produce ineffective solutions to the problem. Many executives insist that there is no time for any meaningful analysis. Yet one of the quickest ways to generate improved performance is by analyzing exemplary employees. Chapter 7 examines the power of these top performers and explores how managers can learn from these best employees in doing performance analysis and improvement.