Chapter 9

Step 7: Implement Change to Support a High-Performing Workforce

![]()

If something's worth doing, it's worth doing slowly.

![]()

A big part of any effort to correct performance problems involves implementing the initiative and managing the change. Any effort to improve results or correct failings will involve changing how the business operates and implementing something new. How do you design solutions and then implement them so they not only work but also have staying power? These are important considerations that too many organizations get wrong.

It's a bad assumption to believe that smart, capable people dedicated to their job will act for the better or embrace changes that seek to improve things. Pfeffer and Sutton detail one specific example of a talented organization that still resisted change:

NASA's space shuttle program provides a painful illustration. It is a classic case of smart, hardworking, and well-meaning people trapped in a system with such ingrained flaws that even a horrible accident, the Challenger shuttle explosion in 1986, didn't change it much. That is the conclusion reached by the Columbia Accident Investigation Board, a blue-ribbon panel charged with determining why the shuttle Columbia disintegrated upon reentry on Feb. 1, 2003. (Pfeffer and Sutton 2006, 96)

Good ideas don't automatically result in adoption. A talented organization doesn't always embrace change. The process of implementation for any performance improvement program is always problematic.

Change Done Wrong

![]()

It's generally much easier to kill an organization than to change it substantially.

![]()

Many executives pay lip service to the importance of managing change (Schneider 1999). Typically, however, most organizational initiatives and change efforts are done in a hurry with little or no follow-through. The rate of change and the number of new initiatives often has the affect of slowing things up and certainly reduces the likelihood of success. Pfeffer and Sutton note that

much the same thing happens when companies introduce too many new management practices too fast. During research on our book The Knowing-Doing Gap, we found the “flavor of the month problem” was one of the biggest impediments to turning knowledge into action. Senior executives would introduce new programs at such high rates that it was impossible for even the most skilled managers to keep pace, plus people didn't think they needed to take the changes seriously since a new flavor would be coming along soon. (Pfeffer and Sutton 2006, 173)

In many companies, the implementation process often takes a very hierarchical approach—it's driven from the top down (Senge and others 1994). Change efforts are frequently based on unidirectional communication coming from senior managers, with no milestones or interim measures of progress. In many instances, for one reason or another, a change will need to be mandated from on high, and it's “my way or the highway.” But it's important for executives to realize that those instances of imposed solutions without user input come at a significant price to both the organization and the likely success of the implementation.

In addition, because such change efforts rarely take a systems perspective on both the performance issue and the proposed solution, problems tend to resurface or executives may feel that they need to do more than the last time around. Peter Senge (1990, 130) concluded that “pushing harder and harder on familiar solutions, while fundamental problems persist or worsen, is a reliable indicator of non-systemic thinking—what we often call the ‘what we need here is a bigger hammer’ syndrome.”

Executives will impose a new idea on the organization without much regard for how it will work systemically and with almost no planning for an implementation effort that engages the system. Or there is often an assumption that implementation is all about leadership and bringing in the right people. Good leaders and great talent are helpful, but they are by no means the critical elements in successful implementation. As Pfeffer and Sutton (2006, 102) admit, “Bad systems do far more damage than bad people and a bad system can make a genius look like an idiot.”

Many assumptions—and even change management fads—that executives use in trying to promote change are just plain wrong. Jim Collins did extensive research on this issue of organizational change and concluded that the vast majority of organizations approach change idiotically:

I want to give you a lobotomy about change. I want you to forget everything you've ever learned about what it takes to create great results. I want you to realize that nearly all operating prescriptions for creating large-scale corporate change are nothing but myths. The Myth of the Change Program: This approach comes with the launch event, the tag line, and the cascading activities. The Myth of the Burning Platform: This one says that change starts only when there's a crisis that persuades “unmotivated” employees to accept the need for change. The Myth of Stock Options: Stock options, high salaries, and bonuses are incentives that grease the wheels of change. The Myth of Fear-Driven Change: The fear of being left behind, the fear of watching others win, the fear of presiding over monumental failure—all are drivers of change, we're told. The Myth of Acquisitions: You can buy your way to growth, so it figures that you can buy your way to greatness. The Myth of Technology-Driven Change: The breakthrough that you're looking for can be achieved by using technology to leapfrog the competition. The Myth of Revolution: Big change has to be wrenching, extreme, painful—one big, discontinuous, shattering break. Wrong. Wrong. Wrong. Wrong. Wrong. Wrong. Totally wrong. (Collins 2001)

For Collins, widespread and long-lasting change occurs from what he calls the “flywheel” effect, which means that change takes a long time and a lot of effort but eventually becomes contagious—just as a flywheel eventually builds up power and force.

Perhaps another perspective to take toward effective implementation efforts is the challenge of building a habit. It's often not that difficult to artificially or superficially change a process, rewrite a position, alter benefits programs, or raise work standards. But systems adapt to changes, often by subsuming them. For a change to persist, the new behavior or standard needs to become a habit. And organizations don't build new habits quickly. If an executive is truly committed to an initiative, is there enough staying power to make this program the organization's top priority for the next two to three years? A time frame of this length probably sounds wildly unrealistic given the tempo of modern organizational life and the need to respond to emergencies and sudden changes. But a fair assessment would be this: Unless there is a long-term commitment that engages the organization on a systems level, no program will become a habit.

William Schneider (1999) studied the power of organizational culture on change efforts and found that “it may look like an intervention is working in the short term, but what is usually happening is the living system is yielding short-term financial cost savings which start creeping back over the intermediate and long term. This is most evident in the example of ‘surgical’ interventions, such as reengineering, delayering, and downsizing.”

Quick fixes, sudden changes, fast programs, and overnight initiatives may enjoy some early success if they are indeed a good fit, but they will not last without a sustained commitment to see them through. This means that the ability to produce true change by engaging the system and sustaining the program beyond a quick fix stage is critical. As Pfeffer and Sutton (2006, 145) note, “That is why Richard Kovacevich, CEO of the large and tremendously successful Wells Fargo Bank, has repeatedly argued that organizational culture and the ability to operate effectively—successful implementation—is much more important to organization success than having the right strategy.” This also provides detail to Collins's flywheel approach—lasting change rarely occurs quickly and takes a sustained effort that eventually does more than just alter a process or structure; it also engages the system and also causes it to evolve in ways that support the initiative.

Organizational culture, as discussed earlier in this book, must be a factor in any performance analysis yet is just as important on the implementation side. Management teams that fail to take a systemic view in planning implementation usually end up ignoring or underestimating the ability of the organization's culture to overwhelm and undo any proposed change. Some go so far as to argue that an organization's culture is the single greatest factor in determining the success or failure of any program. According to Schneider (1999), “If the management idea fits the nature of the organizational culture, it will most likely work. If not, it will most likely fail.” Thus, one important aspect of taking a systems view of implementation is accounting for the organization's dominant culture.

Systems and Change: The Six Sigma Example

![]()

When discrete techniques (such as [just-in-time], simultaneous engineering, supplier quality audits) are applied to enterprises with neither the philosophy nor the organization to accept them, they fail to produce results. The same is true of process automation or automated information systems. Philosophy and organization must precede technique.

![]()

Six Sigma is a process used to reduce mistakes or defects while improving service. Generally acknowledged as having emerged out of Motorola (Ramias 2005), Six Sigma was pushed by then–GE CEO Jack Welch as an invaluable tool for organizational success. Some organizations, such as Motorola and L.L. Bean, have had good results using Six Sigma. But evidence from a range of sources has indicated that most other business that have attempted to jump on the Six Sigma bandwagon have had no success whatsoever (Holland 2007).

The typical approach for most organizations is to send some employees off to training to become Six Sigma “black belts.” These individuals then typically return to the organization with two missions. First, they are supposed to spot problems and solve them. Second, they are usually responsible for training others in the Six Sigma tools.

There are multiple problems with this approach. The effective result is that the black belts return to an organizational culture that is not supportive of the Six Sigma approach. The rest of the organization is used to the status quo and isn't designed to work with a Six Sigma effort. And the new Six Sigma cadre typically returns to a business with no processes, resources, or structures set up to facilitate their work. Other than their training and perhaps a few public statements by senior managers, nothing has been done to support them.

There is nothing about parachuting black belts into a business that indicates any kind of systems perspective within the organization. As a result, this approach is very similar to the way that most fads in business are implemented, and it also tends to produce the same results. According to Industry Week, “Many certified Six Sigma black belts are as useless in factories as they are in dark alleys. They're being churned out of four-week seminars that are offered by every business school in the country. Dropped into facilities with a mandate to save the company hundreds of thousands of dollars every year, these certified but inexperienced statistics wizards have failed to deliver in many cases, discrediting the whole endeavor” (quoted by Drickhamer 2004).

This type of experience with Six Sigma has been repeated by too many companies. Many lessons can be learned form this experience. Probably the most crucial is the need to take a systems perspective on problems and to implement solutions systemically so that they're more than just solutions imposed on the business or resources parachuted into the existing structure. Approaches like that are doomed from the outset (Schneider 1999).

Understanding the System

![]()

In virtually every organization, regardless of mission and function, people are frustrated by problems that seem unsolvable.

![]()

The perception of unsolvable or persistent problems within the organization is usually an indication of a lack of systems thinking. It's critical for managers to not only take a systems perspective toward performance but also to understand their organization's internal system dynamics. According to Senge (1990, 144), “We are conditioned to see life as a series of events, and for every event, we think there is one obvious cause…. Focusing on events leads to ‘event’ explanations…. They distract us from seeing the longer-term patterns of change that lie behind the events and from understanding the causes of those patterns.”

Thus, taking a more holistic perspective is critical for successful implementation. Without a systems perspective, most initiatives will flounder because too many variables weren't addressed in the implementation plan and the system will end up overwhelming the program (Schneider 1999).

![]()

Many “best practices,” though useful for illustrative reasons, are not ultimately implemented, because they don't come with sufficient context to be successfully applied.

![]()

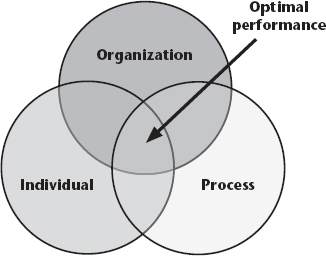

A number of approaches can be helpful in gaining a systems perspective on both the performance and also implementation issues. Geary Rummler and Alan Brache (1995) developed a useful model for both analyzing performance systemically and providing necessary insight for implementation. Their idea of looking at organizational, process, and performance issues is an effective way of gaining a more holistic perspective; see figure 9–1. Process maps can also be helpful. Although they look at only one aspect of the system—the specific process being mapped—they provide a much more integrated perspective on the work than do most analyses.

Archetypes are another approach that can be invaluable in promoting systemic analysis and a greater awareness of the how the apparently independent aspects of the organization are actually related. The example of the “fixes that fail” archetype was mentioned in chapter 1. These archetypes help explain how systems function by looking at the dynamics and the forces that serve to reinforce particular organizational behaviors. As a result, system archetypes can help explain why some problems seem to persist, or why an organization seems to lurch from boom to bust in a never-ending cycle, or why the business has to keep upping the dosage of whatever solution is uses—how a fix appears to be only short term and seems to require a bigger effort the subsequent time.

Figure 9–1. Rummler's Model of Optimal Performance

Source: Rummler and Brache 1995. Used with permission.

Because system archetypes help to explain what produces particular dynamics, they are not only useful for diagnostic purposes but also helpful with implementation of solutions. Archetypes clarify what system forces work against the solution, what loops to reinforce, and which ones to try to mitigate so the new program isn't overwhelmed by the organization.

Remember, it's not enough to analyze the problem systemically—you also need to look at the solutions from a systems perspective. Generally speaking, this will mean that any changes will almost always have these characteristics:

• There will be more than one solution or initiative—there is no simplistic mindset that major problems are the result of one cause.

• Using Rummler and Brache's model, the solutions need to act at the organization, process, and performer levels. In other words, solutions do not engage just one aspect of the system.

• Recognizing that quick fixes usually have long-term problems, any systemic response will recognize that serious change doesn't happen quickly and dedicate resources and support for the long term. There is no talk of quick turnarounds, and there is an obvious commitment for a lengthy period of time.

• The change takes organizational cultures into account. Efforts to transplant ideas from other organizations also look at the support systems in place at the original organization. Initiatives are tweaked so they don't run afoul of internal cultural factors.

Any significant organizational change that doesn't have these traits is probably not a systemic change and therefore has a very high chance of failing over time.

Getting Commitment

![]()

Individual commitment to a group effort—that is what makes a team work, a company work, a society work, a civilization work.

![]()

Another factor that influences the success of any initiative to improve performance is the degree of support it receives from employees. The terms “commitment” and “buy-in” are often loosely thrown around by managers during a time of change. Getting commitment means getting a degree of ownership such that participants treat that initiative as their own. It means more than just following the rules or going along. Commitment means acting as if you own the business, as if the initiative is your idea and one that you are passionate about. Yet true commitment isn't achieved easily.

Three things need to occur to achieve commitment from individuals (Senge 1990). First, the manager asking people to make a commitment needs to model the behavior or actions being asked of others. You can't ask the staff to buy in to longer hours during the holidays if the senior executives don't set an example. To put this another way, you can't ask people to make a commitment if you won't yourself.

Second, the manager needs to level with people. It's OK to try selling them on why something needs to happen. But the players must believe they have been told the truth—that negative aspects weren't held back. If there is a perception that management hasn't been honest, it provides a copout for employees.

The third necessary element for commitment is choice: Employees need to have the ability to say no or opt out. Now there are certainly times when organizations can't afford to give people a choice of whether or not to go along with a particular policy or initiative. But the reality of such a situation is that in any instance where there was no opportunity to truly choose, there cannot be commitment. There may be strong compliance. You may see lots of hardworking and dedicated employees putting in extra effort out of loyalty to the company or the manager asking it of them. But you will not see commitment—where everyone acts as if it was their own business with their own money at stake rather than someone else's. Commitment is rare, especially when dealing with organizational change.

![]()

Setting an example is not the main means of influencing another, it is the only means.

![]()

Even in instances where management isn't asking for commitment but just compliance, it's important to look at the example being set. Employees may not ever be at the level where they feel they “own” the initiative, but they certainly need to move past being tempted to sabotage the effort or grudging obedience to the plan. And the single most important factor in achieving at least some degree of “followership” is for management to set the example (Riches 2007).

There is a common misperception about organizational change and resistance. Too many managers believe that people generally resist change. But that perspective fails to really explain why resistance is so often pervasive. As Senge (1990, 233) likes to say, “People don't resist change. People resist being changed.” Very rarely is the opposition to change itself. Usually the pushback and resistance are occurring because people don't like what they think is being done to them.

Maximizing the Implementation Process

![]()

Pick battles big enough to matter and small enough to win.

![]()

In effectively implementing a new initiative, managers and staff need to focus on many details. But there are four basic rules to follow:

1. Be consistent.

2. Look for quick successes.

3. Symbolize the new identity.

4. Celebrate the successes.

Let's look briefly at each.

Rule 1: Be Consistent

Your message must be consistent. Every policy, procedure, and list of priorities sends a message. You need to make sure that your messages don't contradict. If there is a new initiative to generate a greater number of sales leads but the company doesn't remove anything from the list of tasks for the sales reps, then there is a conflicting message. People may get the message that they are expected to cut corners or that the new program isn't really important.

The management efficiency expert W. Edwards Deming often referred to the classic example of inconsistency within organizations that move to team-based structures yet continue to evaluate, promote, and pay performers individually (Pepitone 2000). Look for ways to model the behavior you want. Use your actions to demonstrate your commitment to the change as well as the level of priority. Most important, take a systems perspective to be sure that what you're doing is consistent with the rest of the organization—or make changes in the system.

This means, for example, that if the organization wants to improve the autonomy of its software coders, it will also need to make changes in the benefits and salary structure, reporting process, position competencies or competency model, and appraisal standards. It will need to identify which elements of its culture are inconsistent with this new initiative of “greater autonomy for software coders.” The rule of consistency sounds simple but is actually quite involved, and most organizations violate it in attempting to implement a new performance-oriented program.

Rule 2: Look for Quick Successes

People need some early victories to build on initial support for an initiative or convert doubt into support. Keep the flywheel effect in mind—to build support and keep people going for the long haul, you need some early wins. Even if these initial wins are small ones, they can play a vital role in keeping people engaged with the change. Without early progress, believers begin to doubt and doubters turn into critics. Look for ways to build quick wins into the process as a means of building commitment and reinforcing belief.

For instance, if the initiative involves some kind of training, then it's important to find ways for the newly trained performers to feel comfortable with the new skills and enjoy some early payoff from using what they have learned. This results in reinforcement, which encourages the employees to continue to use the new skills (despite the inevitable learning curve that is the result of any training).

Rule 3: Symbolize the New Identity

Symbols convey messages that reinforce new behavior or changes. Symbols appeal to our emotions and often carry much more meaning then we recognize. During highly charged and emotional times, everything takes on meaning. Employees perceive even small accidents as intentional. Therefore, it's important to view everything symbolically and to look for ways to use it to your advantage. Who gets invited to meetings and what is at the top of the agenda? What behavior does upper management point to as exemplary? When the new initiative is announced, who stands next to the executive kicking things off—the union rep? If the organization has a poor track record implementing programs, is this new initiative announced in the same way as most of the others have been kicked off?

Rule 4: Celebrate the Successes

It is critical to recognize success. Organizations that have good track records implementing programs also are good at rewarding outcomes. So throw a party to let people know where they are on the path, how close they are to the end, and the degree of progress. Have fun and let everyone know that the organization has made a new beginning or reached an important milestone. Even if the timing is a bit arbitrary, use this party to decrease the level of uncertainty that is part of the transition (“How much longer is it?” “Are we there yet?”). Let personnel feel a sense of accomplishment and acknowledge their achievements.

This celebration is an opportunity to reward people for taking risks as well as being successful. It's also a chance to help evolve the organization's culture from one that sees a new initiative as a likely candidate for “flavor of the month” to one that instead sees opportunity and thinks success is possible. This does not mean that many parties lead to success—only that even quick, informal celebrations and acknowledgment can help immensely.

Another way to increase the likelihood of a successful implementation is to study past failures. More specifically, you'll gain tremendous insight by looking at other failed initiatives within your organization. What went wrong? Why was there no buy-in? Who opposed it? What mixed messages did people get about the program? A success from the past tells you little—it may involve resources or circumstances that you can't duplicate. A failure is much more revealing about both an organization's culture and the potential barriers it may pose to future initiatives.

Performance Solution Notebook

![]()

For all the examples of health care organizations that have mishandled health-care-acquired infection (HAI) programs, there are also an increasing number that have gotten it right and improved their performance tremendously.

A critical element of any comprehensive HAI program is hand hygiene. Yet too many facilities have abysmal rates of compliance. Or some experience a very brief period of success followed by a continuing drop, ultimately resulting in a return to the previous low standard. As Linda Greene, an infection control expert at Rochester General Hospital notes, “One of the main issues with hand hygiene campaigns is sustainability” (quoted by Beaver 2007, 2). One health care alliance in Pennsylvania made impressive initial HAI progress by implementing a series of initiatives, from new metrics that allowed for timely and actionable data to a Toyota-like quality control process that allowed the unit to systematize and monitor potential infection interactions. The efforts involved engineered solutions that looked intelligently at outcomes and accomplishments, broke down work by tasks, and determined the root causes of performance breakdowns. But the alliance was unable to either spread the program to other units or sustain it, and after the head of the program left, HAI infection rates worsened (Gawande 2007).

However, the health care alliance was able to regroup and significantly reduce HAI rates by adopting new approaches to implementation. For starters, the new heads of the program took a different tack. Even though they had a good idea of what the program needed to be to reduce HAIs, they went to the facility staff and asked for their input. Jerry Sternin, a nutritionist who was involved in the follow-up program, noted that “after the eighth group [we sought input from], we began to hear the same things over and over. But we kept going even if it was group number thirty-three for us because it was the first time those people had been heard, the first time they had a chance to innovate for themselves” (quoted by Gawande 2007, 26).

Another key element to the health care alliance's follow-up program involved an evolution in its organizational culture and many incremental victories. Staff who felt wearing gloves with patients was a silly idea were approached by their peers. Atul Gawande (2007, 26) commented that “nurses who would never speak up when a doctor failed to wash his or her hands began to do so after learning of other nurses who did” and “the team made sure to publicize the ideas and the small victories.” Lessons from a different facility that had also found success with their HAI program generated this lesson: “Motivating staff members to be hygiene compliant doesn't have to involve one juggernaut approach. It can instead comprise lots of small and medium measures” (Beaver 2007, 1). As we've seen throughout this book, there are usually multiple causes for any performance problem, and rarely is there one magic bullet for the problem.

Programs that have looked seriously at sustainability and implementation have found new insights about HAI efforts. Maryanne McGuckin of the University of Pennsylvania noted that “study after study shows that no matter what you do in terms of education, hand hygiene compliance is short term and relatively unsustainable. Current programs have about a 20 percent compliance rate. We must change the culture by involving the patient…. We now have more than 400 hospitals supplying data,…and the bottom line is once they involve the patient, they get to almost 100 percent hand hygiene compliance” (quoted by Pyrek 2006). Recognizing the importance of the organization's culture and finding ways to evolve it to support initiatives is an important insight for effective implementation and ultimate program success.

The Pennsylvania health care alliance's follow-up program also involved detailed observation, plus preadmission and postadmission data gathering. Data was also gathered monthly and posted by unit—both creating baselines and adding a competitive element to the implementation. No unit wanted to be seen as having the highest infection rate, while this approach gave others a chance to celebrate progress. After a year of this follow-up program, the hospital had an MRSA (methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus) infection rate of nearly zero. The program has been so impressive that the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and the Jewish Healthcare Foundation have funded a multi-million-dollar program to try a similar approach in 10 more facilities across the United States (Gawande 2007).

Hitting the Mark

![]()

This chapter has offered a number of insights about producing and sustaining change within an organization:

• Change requires time if it's going to be sustained. It's about making something a habit, not a temporary fix.

• Significant problems in organizations never have just one cause, so seeking a simple solution will fail. Smart leaders recognize that improving performance will usually require several initiatives, and any time a single scapegoat or cause has been identified then the analysis is too simplistic.

• If the change doesn't occur at a systems level and take into account the organizational culture, then it will almost certainly fail. Smart managers create solutions that engage organization, process, and performer levels.

• The implementation process is critical. Smart organizations make sure they're consistent (easier said than done), structure in early successes as a way of building momentum, use symbols effectively, and celebrate successes along the way.

Organizations are continuously looking for ways to generate better results and fix performance issues. But most of these efforts consist of actions doomed to failure. Doomed because they involve no in-depth performance analysis. Doomed because they are based on inaccurate assumptions about human performance. Doomed because they are driven by beliefs rather than data and evidence that is specific to the situation. Doomed by simplistic implementation or a failure to take a systems perspective. But this waste and failure do not have to be inevitable—if managers are willing to think about performance issues rather than opt for the latest flavor of the month or promise instant results.

Looking for a quick fix, hot fad, or fast solution is a prescription for wasted resources and a failed effort. A willingness to actually think, gather evidence, look at the system, and build solutions that fit the business—this is the approach that works. The irony of a systematic approach to performance is that it actually produces results more quickly and more consistently than approaches that appear to be faster. Resist the temptation to look for the false promises of a magic bullet. In the end, you'll be more effective and get results faster. The last chapter ties together the recommendations from the rest of this book to give you a detailed road map to improved performance.