Chapter 1

Quick Fixes, Band-Aids, and Fads: A Road Often Traveled

![]()

Historically, what held back progress in education is people looking for the “single shot solution.” The one big program. The one big, new way of doing things, the one big new revolution. And people, of course, get tired of that. We all know that is never a single program, never a single shop, never a single moment, never a single silver bullet.

![]()

Abandon the urge to simplify everything, to look for formulas and easy answers, and to begin to think multi-dimensionally.

![]()

Organizations spend billions on efforts to get better. But too many of these initiatives are either flops or only fleeting successes. A careful look at these experiences shows that businesses are too quick to go with programs that have little or no chance of success. There are many of reasons why organizations adopt faddish ideas that don't work or won't commit the time and resources to make a new initiative successful. Yet as counterintuitive as this process of jumping from fad to fad seems, it's a common way of doing business for the vast majority of organizations in the West.

![]()

The search for the one quick fix is a universal human failing.

![]()

This focus on a quick fix is not limited to just Fortune 500 firms or a particular business sector. Many executives have tried to copy initiatives by industry leaders. For instance, whatever CEO Jack Welch proclaimed as GE's latest initiative was often copied by others who thought that if only they tried the GE workout process or used forced rankings, then their company's performance would match GE's.

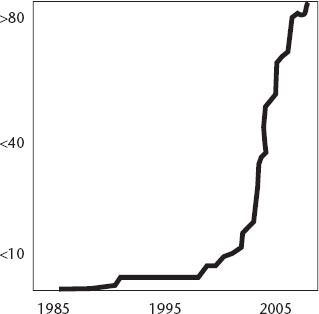

Hundreds of best-selling books—from The Goal to The Secret to Re-engineering the Corporation—have tried to show the way to organizational success. Thousands of consultants have made lucrative careers hawking new programs that would supposedly unlock the door to great results. And many current and former CEOs have gotten rich off of the lecture circuit or through books about the tricks to quickly turn a loser into a successful business—like the management strategy Six Sigma (see figure 1–1; for more on Six Sigma, see chapters 3 and 9).

Figure 1–1. The Popularity of Six Sigma: Number of U.S. Fortune 100 Firms Using Six Sigma

Source: Business Week, “Six Sigma: So Yesterday?” June 11, 2007, available at http://www.businessweek.com

Some claim that this focus on fads is a function of a consulting industry eager to make a quick buck by pushing the latest and greatest. The argument is that consultants have been exploiting businesses by peddling expertise they don't have or pushing the organizational equivalent of snake oil. But this is more than just a case of consultants as peddlers of slickly sold solutions that won't work. There are just as many instances of internally driven fads that can't be blamed on a persuasive consulting firm. A CEO copies a competitor or a manager seeks a fast turnaround with the latest hot program—these internal examples are just as prevalent as any involving consultants.

What these fads have in common is that regardless of who is pushing them, they involve both some kind of quick fix and a simplistic approach to the problem. The initiative is often expected to be a magic bullet that transforms the organization. Or managers see the new program as something that will quickly solve what ails the business. In either case, the program assumes that the organization (and the performance it produces) is simple and that improvement will come either quickly or by dealing with one or two key issues.

![]()

People are always looking for the single magic bullet that will totally change everything. There is no single magic bullet.

![]()

There is very little evidence that getting sustained results is that simple, easy, or quick. If that were true, then executives wouldn't be so worried about the future performance of their workforce and the long-term competitiveness of their organization. When managers make decisions to adopt programs that aren't well thought out, lack depth, or have no sustained organizational commitment, they're doing the equivalent of slapping a Band-Aid on a serious wound while believing the problem requires no further attention. This leads to both a nonsolution and an approach that will probably makes things worse.

Getting better results is rarely a function of finding one magic fix or a quick answer that makes everything right—human organizations aren't that simple. As the surgeon Atul Gawande (2007, 21) notes, “We always hope for the easy fix, the one simple change that will erase a problem in a stroke. But few things in life work this way. Instead success requires making a hundred small steps go right—no slipups, no goofs, everyone pitching in.”

Flavor of the Month

Although it's good that most organizations are eager to improve and want to gain competitive advantages, there's a difference between jumping on a fad and making a sincere effort to solve a problem. Too many organizations go about this the wrong way. They tend to rely on quick fixes as a way to achieve better results. But the majority of such changes—despite the reasons given for their adoption—prove to have little or no value.

![]()

Global business leaders have long been searching for management wizards who will magically bestow greater productivity, lower costs, expanded market shares, world-class competitiveness, swifter speed to market, continuous improvement and instant innovation. With great excitement and fanfare, these wizards have taken the world's largest corporations on breathtaking adventures down attractive but imaginary paths to Oz, where the leaders eventually discover more make-believe than make-it-happen.

![]()

Today, new fads and the latest flavor of the month are emerging more and more quickly. The Wall Street Journal has noted that “the ideas are coming and going more quickly than ever, some researchers say. A 2000 study by professors at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette on 16 ‘management fashions’ in the past 50 years found that idea life cycles are shrinking. From the 1950s to the 1970s, it typically took more than a decade for interest in an idea, measured by press mentions, to peak. By the 1990s, that interval had shrunk to fewer than three years” (Dvorak 2006). David Strang and Michael Macy of Cornell University examined how frequently businesses adopt new approaches to improving organizational results. They found that an “examination of many innovations suggests empty rhetoric and shameless self-promotion.…Whether productive, ineffectual or downright harmful, it is evident that organizational change in American business is faddish” (Strang and Macy 1999, 1).

In short, many of the hot new trends offer little or no value. But this doesn't stop them from acquiring corporate advocates who enthusiastically invest in them. “Substantial numbers of firms thus coalesce around specific worthless strategies that have recently been tried with extraordinary but fleeting success. They typically abandon these strategies in short order as new winning strategies arise and their own experience with yesterday's winner proves mediocre” (Strang and Macy 1999, 1).

![]()

Managers tend to treat organizations as if they are infinitely plastic. They hire and fire, merge, downsize, terminate programs, add capacities. But there are limits to the shifts that organizations can absorb.

![]()

The perception that businesses focus on a flavor of the month and jump from trend to trend—which is almost universal across North American companies—ultimately reduces managers' credibility for future initiatives, leading to wasted resources and lost opportunities. It also institutionalizes a way of making organizational changes that impedes lasting improvement. This last point can't be emphasized enough: When a business repeatedly chooses ineffective initiatives or implements them poorly, it creates a culture for how it makes improvements.

Five Reasons to Love Quick Fixes

A competitive world places tremendous pressure on organizations to continuously improve. This competition isn't bad, because it can spur innovation and also punish organizations that fail to adapt. But competition doesn't have to produce organizations that jump from fad to fad, seeking a magical solution to problems. In fact, most organizations remain remarkably immune to competitive pressures by continuing to insist on initiatives that have been shown to fail.

So why do most organizations insist on approaches that won't work? You'd think that organizations would be motivated to do it right and to avoid snake oil solutions. After all, decisions that involve major changes and risks aren't things you'd expect management to take lightly. Furthermore, so many senior managers usually have such big personal incentives for organizational success that it would seem crazy for them to adopt programs that are going to fail. You'd think that most businesses would have good reasons to make smart choices and then do it right. So why are quick fixes so prevalent in modern organizations? There are five consistent reasons:

• We want it fast and painless.

• We have no real commitment to making it work.

• We fail to truly understand performance.

• We treat the business as a series of independent, simplistic elements.

• “Me too”—we must keep up with the Joneses.

Let's briefly look at each reason.

Reason 1: We Want It Fast and Painless

For a variety of reasons, when it comes to making an organization better, people aren't usually patient or focused enough to tolerate something that requires staying power. Sometimes, so many things are broken within a business that the leader is in a hurry to get one thing checked off his or her to-do list and move on to the next item. Other times, these is a bias for action—but not for results. Managers thus can say that something has been “done” when, really, a program has been rolled out with little focus on results or on things that have actually gotten better.

Also, a fast and painless approach points to an unwillingness to measure true results. It's a lot easier to hire a new manager (or adopt a different benefits program, or train all the sales staff) and then declare victory than it is to make the change, tinker with it, and continuously measure it for a year before concluding that results have gotten better.

Reason 2: We Have No Real Commitment to Making It Work

The organizational change consultant Geoff Bellman likes to tell clients that “if it's worth doing, it's worth doing slowly” (and Bellman then acknowledges that he's quoting the late Mae West). This sounds counterintuitive in a world where things appear to be moving faster and faster. How can any organization succeed in this fast-changing world if successful initiatives take a long time to implement? The point isn't that organizations can't act quickly, only that something takes time to truly succeed. Quick actions don't become embedded in the culture and don't become habit.

Reason 3: We Fail to Truly Understand Performance

Because many managers have a very poor and simplistic perception of what contributes to human performance and how to improve it, they misdiagnose work issues and then can't find effective solutions. As a result, many wrongheaded approaches get foisted on employees—ranging from a focus on behavior to throwing training at problems to the belief that hiring the most talented people equals success. Other organizations have bought into the approach advocated by “the war for talent” best summarized as “get talented performers and you get good performance” (among much that has been written on this “war,” see, for example, Fishman 1998). Other simplistic approaches seen repeatedly in organizations—despite the lack of evidence that they're appropriate—include pay for performance and efforts to improve morale.

A classic example is the arena of lean manufacturing popularized by Toyota. Hundreds of manufacturers have copied the techniques that Toyota espouses but have failed to acknowledge how the Toyota culture as well as many other factors (the Toyota employee involvement process, the mindset, the organizational focus) shape the success of the lean manufacturing process.

How organizations analyze and respond to individual performance issues is just as typical. For example, an organization might send managers to training because they exhibit poor collaboration skills and the firm's competency model indicates that these skills are critical. These managers may score poorly on their 360-degree assessment because their work role penalizes them for taking time to collaborate and places a premium on speed of execution. As a result, even after they complete their collaboration skills training, she will still score poorly in collaboration.

Reason 4: We Treat the Business as a Series of Independent, Simplistic Elements

Organizations are systems, which means that they consist of a number of apparently independent parts that actually interact and influence each other. The operational reality of a system is that many factors contribute to results, the various parts of the system interact with each other, and changes in one part can unintentionally change other parts or be overwhelmed by the rest of the system (which can serve to reinforce the old way of doing things). As the consultant Geary Rummler has said repeatedly, “Pit a good person against a bad process and the bad process will win almost every time.”

Reason 5: “Me Too”—We Must Keep Up with the Joneses

Many corporate changes occur because of the business equivalent of “keeping up with the Joneses.” Simply, a CEO or division director sees or reads about something a competitor is doing. In a desire to not be left behind competitively, the executive orders his organization to do what the competition has implemented, for a range of initiatives, from strategies (business process reengineering) to management (Six Sigma) to structure (offshoring). This can often be seen in industries where the market leader touts a particular program and competitors then rush to copy it—whether a good fit or not. This is part of the reason that Tom Peters has decried competitive benchmarking—the tendency of firms to mimic what others do.

For instance, many firms now have 360-degree assessment programs (where a manager is evaluated by superiors, peers, and subordinates, and sometimes customers or vendors as well). Some organizations have begun touting “450-degree assessments,” which are supposedly 360-degree assessments that now include customer input as well. As a consultant, I had two potential clients contact me in their search for someone to implement a 450-degree assessment system for their firms. Yet both organizations already had 360-degree systems that included customer feedback on performance.

Why Quick Fixes Don't Work

![]()

Top-down change—such as reengineering and rightsizing—often fails because it disturbs all the smaller systems that make up the larger system. In the name of simplifying and streamlining, top-down change actually introduces turbulence in the form of workarounds, passive aggression, and reinvented wheels.

![]()

Executives often pay lip service to the importance of organizational culture and to how difficult it is to change things within an organization. But most initiatives fail not because the resistance is too great but because the program fails to take a systemic approach to the organization. In other words, too many change efforts approach a problem as if it were isolated, when in reality many factors come together to interact and shape results. To focus on only one or a few elements is to ignore how many aspects of the business interact to shape results.

All organizations are systems. Any time an effort is made to change one aspect of an organization, other pieces of the system play a role. This may mean that unintended consequences emerge. As tempting as it is to find a magic button to push, performance issues are rarely that simple, and achieving successful change is rarely that easy.

![]()

I believe that our very survival depends upon us becoming better systems thinkers.

![]()

Think of the number of times you've seen this response to business changes or customer input:

• A business gets complaints about service quality or sales go down, so frontline staff are sent to customer service training.

• Whether the training addresses the right problem or not, it will almost certainly fail because the organizational response lacks a systems perspective.

• The training fails to look at other factors (other than the knowledge and skills of the staff) that likely contribute to service issues; it doesn't consider how the organization rewards poor service (it must, if the service issues persist over time and are widespread) and how existing processes make good work difficult.

Coaching May Not Be the Answer

Even efforts to try to move beyond a simplistic, one-shot effort (such as combining an executive coaching program with a new incentive program and changing the hiring process to improve executive retention) often fail. Treating a problem with multiple programs may be less simplistic in terms of implementation or resources, but it isn't any less simplistic from a systems perspective.

Despite the diversity of organizations, with their host of different problems and multitude of dissimilar solutions, their system dynamics end up being remarkably similar. The dynamics generally follow this pattern: management becomes aware of a problem, a quick solution is sought, new (or connected) problems emerge, the organizations fails to see the connection to the original problem and solution, someone is made scapegoat, someone is rewarded (usually the wrong person), and the process repeats itself (Kim and others 1994).

Performance Solutions Examples

Throughout this book, examples help illustrate key concepts and critical points. The health care case study presented in the Performance Solutions Notebook of each chapter (except the concluding chapter 10) examines one aspect of this issue in terms of performance, showing how health care organizations and professionals have dealt (both effectively and ineffectively) with the problem of health-care-acquired infections in terms of the topics covered in the particular chapter.

Performance Solutions Notebook

![]()

Health-care-acquired infections (HAIs) are a significant and costly problem around the world especially in the United States. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control estimates that each year, 2 million Americans acquire an infection while in the hospital, and some estimates put the number of deaths in this country from these infections at 90,000 (Gawande 2007). To put this in perspective, approximately 1 in 20 hospital patients contracts an infection during their treatment. Furthermore, a type of infection referred to as an MRSA (methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus) is of particular concern because it is a staph infection that has become invulnerable to front-line antibiotics. Data for the United States shows that the deaths associated with MRSAs in this country exceed those from AIDS (Stein 2007). So, clearly, HAIs are a very serious problem.

Understanding the response to HAIs is especially helpful in gaining insight into organizational performance. An HAI is an instance where an infection is acquired in the hospital—a case in which the health care system appears to have made a patient's health worse rather than better. Furthermore, examination of infection rates of HAIs show that they vary greatly by hospital and by country. In other words, this is not a problem with a uniform incidence rate across facilities and countries—obviously, variables result in some facilities or countries with low HAI rates but others with ones that are much worse. For instance, HAI infection rates in Sweden and Norway are nearly zero (Berwick and Leape 2006). Medical professionals, in the way they interact with patients and other staff as well as how they do their jobs, determine the incidence of HAIs (Gawande 2007).

How the health care field has dealt with infections illustrates the points made in this chapter about fads, a lack of commitment, and failure to take a systemic approach to dealing with infection. For starters, the emergence of MRSAs is due in great part to a tendency to look for exactly a magic bullet—one solution that quickly fixes the problem without requiring changes in the system or the involvement of others. Too many health care providers (as well as patients) have viewed antibiotics as a magic bullet. The response to a range of health concerns in the past has often been to rely on antibiotics as a prophylactic and to prescribe them as a precautionary measure before tests demonstrated if the drugs were appropriate. As a result of this behavior, much of the development of drug-resistant strains is due to an overreliance on antibiotics (Stein 2007).

However, there have been other simplistic or trendy responses by health care providers to HAIs. Health care is one industry that is guilty of flipping from fad to fad and lacking staying power on many initiatives. According to Kevin Barcelos, who had worked at a California Medical Center that reduced one type of HAI infection rate by 30 percent, health care “seems to be very cyclical sometimes. You do something and then a couple of years later you undo it and then a few years later you're doing it all over again” (quoted by Beaver 2007, 2). Despite the growth of evidence-based medicine, too many practitioners still don't rely on quantitative data but instead act on anecdotal experience. As a result, health care has often been subject to fads in procedures.

Although many health care facilities have declared HAIs (or even a narrower focus on MRSAs) to be a priority, few have stayed the course. There are many examples of facilities that have announced major infection initiatives only to lose interest or change focus (Gawande 2007). In some instances, this has been the result of cynicism produced by so many failed projects and poorly thought-out initiatives. Terri Gingerich, a director for VHA (a health care provider in Texas) noted how difficult it was to get buy-in to one successful program because of all the previous failures: “When this program came along and we started it, people were skeptical that we weren't going to be able to do it, that it was too good to be true, that it was just another thing someone was jumping on the bandwagon” (quoted by Beaver 2007, 3).

Finally, too many health care efforts to combat HAIs are simplistic. Many health care organizations announce new MRSA programs and then hire individuals to oversee enforcement of these initiatives, yet rarely get full compliance from staff, so the programs stumble along, failing to come close to either the level of staff performance or patient health results that are achievable (Gawande 2007). This lack of staff compliance is rarely handled well by most organizations. Some have tried training as a way of getting compliance—failing to understand that training doesn't solve motivational issues. Other programs rely on the equivalent of enforcement police—staff who are responsible for catching peers who aren't following HAI procedures. Some health care organizations and some countries have clearly shown their ability to reduce HAI rates. But most health care facilities in the United States still tend to throw inadequate efforts at the problem, so HAI rates are minimally affected.

Although HAIs continue to grow as an urgent problem and critical performance issue for health care organizations, fortunately, there have also been success stories. Later chapters will look at specific issues in the effort to improve health care performance fighting HAIs. You will see the content from each chapter applied to HAI performance issues as a way of demonstrating application of the concepts and practices in this book.

Hitting the Mark

![]()

![]()

Thinking is very hard work. And management fashions are a wonderful substitute for thinking.

![]()

If organizations are going to do a better job avoiding fads and false solutions, executives and managers will need to become smarter at analyzing performance. Acting on objective data driven by systemic analysis is critical to avoid jumping on the latest fad bandwagon. “If you are willing to do the hard thinking required to practice evidence-based management, if you want to reap its benefits, you need to recognize your blind spots, biases and your company's problems and take responsibility for finding and following the best data and logic” (Pfeffer and Sutton 2006, 219). How can managers avoid falling for the latest flavor of the month and skipping from fad to fad? Part of the answer to this question involves managers' ability to understand and analyze the performance of their employees and then assess what will work. Unfortunately, as you'll see in the next chapter, most managers hold many misinformed beliefs about human performance.

This chapter has pointed out a number of the more common mistakes that people make in their quest to improve things within the organization—mistakes, such as the following, that not only fail to make things better but usually make them worse:

• Simplistic answers for complex problems. The insistence on superficial responses with nonsystemic application continually results in failure or at best a temporary change that is eventually overwhelmed by the system. The lesson here is that successful changes require an understanding of the system and actions that involve the entire system—isolated or single-level actions will almost always be subsumed by the systems within the business.

• Falling for fads. The tendency for managers to continually be sucked in by the latest and greatest, or attempt to copy what an industry leader has done, almost always leads to failure. Businesses need to choose initiatives on the basis of objective data specific to their business, not the hope that the latest and greatest or the actions of a market leader is going to be the answer. There is a big difference between learning from successful companies and just copying one element of what they do. So the key lesson from this is to act objectively and also gain a real understanding of why an organization was successful.

• Seeking a quick fix. The tendency to look for a magic bullet that changes everything overnight is the equivalent of searching for pixie dust or a magic wand—they make nice fairy tales but have don't exist in most organizational realities. Seeking an instant solution is a prescription for failure and is almost always a waste of resources. The insight from this is that real problems usually require multiple solutions and a lot of work for things to get better—there is no all-healing magical elixir that companies can drink.

• No staying power. Too many organizations slap on an idea and then move to something else. An unwillingness to stick with something and invest the support and focus required for implementation will result in failure. So a key learning point is that if something is important enough to require action, it should also be important enough to require persistence and commitment over time.