CHAPTER 3

Input Objectives

Inputs are activities that make up the project or program. They are often dictated by a variety of stakeholders. Inputs include the required resources, cost, and scope for a project or program. Often developed at project conception, they’re not always communicated clearly to all stakeholders, particularly those directly involved. This chapter describes the importance of developing input objectives and provides several examples.

ARE INPUT OBJECTIVES NECESSARY?

Think about a particular project or program. At conception, certain parameters are described or envisioned. Maybe the project is intended for only one division or group of employees and must be completed by a specific deadline or within a firm budget. These parameters help define the scope and nature of the project. Essentially, the parameters describe the inputs in detail, outlining what the organization plans to do, with and for whom to do it, and how much it will cost. Are they necessary? Yes. Are they listed as precise objectives for everyone to see? Not necessarily. Certainly some document or agreement would contain these objectives. The overriding question is this: Does the stakeholder need this information? For some, it might be helpful to ensure that all stakeholders have it, particularly those directly involved. When in doubt, we prefer to err on the side of full disclosure. The more information shared, the less likely misunderstandings will occur.

HOW TO CONSTRUCT INPUT OBJECTIVES

Input objectives follow the same basic design criteria as described in chapter 1. They should be simple, straightforward, precise, and indicate timing and focus. It is helpful at the beginning of a project to write objectives that define the inputs in terms of issues such as resources, people involved, timing, location, and other constraints on the process and delivery. Here are a few possibilities.

TOPICS FOR INPUT OBJECTIVES

Volume/Staffing

The most obvious place to start with input objectives is the people involved. An objective may focus on the number of participants planned in a formal program and may be divided into demographic categories. For example, an objective may read, “Forty percent of participants will be females with five years of experience.” Some organizations want to ensure that upward mobility exists for all employees, particularly female. The glass ceiling still exists in many organizations, and ensuring that women can take advantage of opportunities requires not only learning and development programs, but also an appropriate number of female participants.

Extending beyond gender and counting participants by other diverse characteristics is another consideration. Programs must be in place to ensure that all employees are involved and have equal opportunity to pursue their careers. Still other parameters might be considered, such as length of service. Individuals with the least amount of tenure should receive the most development. Unfortunately, this is not the case in some organizations.

Project staffing might constitute an objective. Total number of individuals involved in a project is sometimes an issue. An input objective might reflect a maximum or minimum number of people, as well as their job status, such as part-time versus full-time employees. For example, in a technology project, the staffing level input objective was that no more than 15 full-time staffers would take part in the project at any given time. Project teams can also be counted. These teams can be assigned by division, department, function, or even different region.

Scope

Scope establishes the limits of a project. These objectives might place boundaries on implementation, participants, or departments directly involved, as well as the specific function or content explored. A project’s scope might also define the total number of hours to be included or the nature of the work to be done. Defining the scope prevents “scope creep,” in which a project starts out with a narrow focus of one or two topics or areas, and then mushrooms, requiring excessive time, effort, and even money.

Audience/Coverage

Perhaps the most important objective category is the coverage by jobs, job groups, and even functional areas. For example, with the current focus on talent management, some organizations implement projects to address critical talent coverage. They do this by defining critical talent and setting objectives for the number of project participants in the critical talent categories.

Another way to address audience is by a particular function, from research and development through sales, marketing, and customer support. This objective identifies the parts of the organization involved in programs. Coverage might also be defined by specific job levels, such as executives, managers, professionals, and nonexempt employees. Many organizations are concerned about particular job groups, such as first-level supervisors. For example, as an individual job category, this important group in an organization should have many learning and development opportunities. When they use their skills on the job, the effect is multiplicative. As they work with their teams, they drive team performance.

Coverage can also focus on specific strategic initiatives. Projects and programs often are aligned with particular strategic objectives, supporting them with implementation issues. An objective might include the total hours and people included in a particular strategic area. This shows current alignment with an important strategy and can be revealing. When particular strategic areas have little or no coverage with programs, action should be taken to devote more resources directly to those areas.

A final way to represent coverage with input objectives is to focus on particular operational problems. An input objective might be written as, “All customer service staff will be involved in addressing our customer service problem.” Several projects or programs aimed at customer service improvement could help meet this objective.

Timing

Timing objectives indicate when certain tasks will be accomplished, milestones will be reached, or an entire project will be completed. These objectives might dictate when certain individuals become involved in the project or even the timing in which the project team is paid. Timing is critical. Without it, accountability might be absent and misunderstandings might prevail.

Duration

The length of time participants are involved in a project is a common input objective. Some organizations track the total hours of involvement to create an impressive image. A more appropriate measure might be the hours spent per person, targeting a specific amount of time for a particular job or job group. Other organizations track the number of hours involved by various diversity groups, including age, gender, and race. For example, for learning and development, some organizations make a commitment to an average number of hours per person. While this is an admirable goal, it might create more activity than actual change.

Setting objectives for the duration of participation is important for learning and development, human resources, coaching, consulting, and meetings and events. These objectives usually focus on the total duration of the program; for example, organizing a three-day conference, conducting a six-month coaching program, or providing a three-day, new-employee indoctrination.

Budget/Costs

The most logical input objective is cost. The cost of projects and programs is increasing, creating more pressure to know how and why money is spent. The total cost of a project is required, which means calculating indirect as well as direct costs. Fully loaded cost information is used to manage resources, develop standards, measure efficiencies, and examine alternative delivery methods.

Project cost sources must be considered. The three major categories of these sources are found in Table 3.1. Project staff expenses usually represent the greatest percentage of costs and are sometimes transferred directly to the client or project sponsor. The second major cost category is participant expenses, both direct and indirect. These costs are not identified in many programs, yet they reflect a significant amount of the total expenditures. The third cost source is payments to external organizations. These include payments directly to hotels and conference centers, equipment suppliers, and services used for the program. As the table shows, some of these cost categories are often understated. Accounting records should track and reflect the costs from these three different sources.

| Table 3.1: Sources of Costs | |

| Source of Costs | Cost-Reporting Issues |

| 1. Project staff expenses | A. Costs are usually accurate. B. Variable expenses may be underestimated. |

| 2. Participant expenses (direct and indirect) | A. Direct expenses are usually not fully loaded. B. Indirect expenses are rarely included in the costs. |

| 3. External expenses (equipment and services) | A. Sometimes understated. B. May lack accountability. |

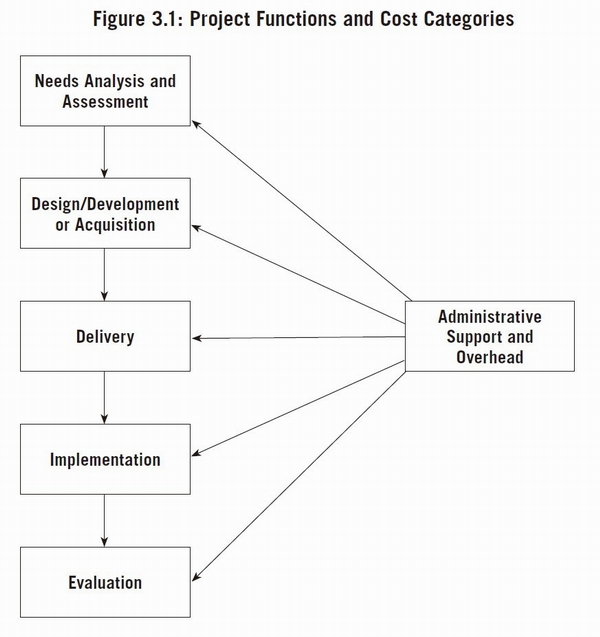

Another key method of developing cost objectives follows the natural project progression. Figure 3.1 shows the typical project cycle, beginning with the initial analysis and assessment and progressing to the evaluation and reporting of results. Input objectives for costs can be developed for each of these steps.

The specific items to be included in the program costs must be defined. Input from the finance and accounting staff, the project team, and management might be needed. The recommended cost categories for a fully loaded, conservative approach to estimating costs are

- Needs analysis and assessment

- Design and development costs

- Acquisition costs (in lieu of development costs, many organizations purchase programs)

- Delivery/implementation costs (five categories)

- salaries of facilitators and coordinators

- program materials and fees

- travel, lodging, and meals

- facilities (external and in-house)

- participants’ salaries and benefits

- Evaluation costs

- Overhead costs.

Efficiencies

Efficiency is measured in different ways and from different viewpoints. One of the first measures is efficient use of the project team. An objective can come in the form of the number of participants per project team member. From an efficiency standpoint, this number should be as high as possible. Efficiency is also reported as content provided per project team member or the average cost per content hour provided. Other efficiency measures focus on the time to accomplish certain tasks—the average time to conduct a needs assessment or to design an hour of content. Other time objectives include the time an individual takes to complete a program or the total cycle time from a request to launch a program to delivery of that program.

Content

Input objectives focus on content in various ways. For example, in learning and development, the percentage of content devoted to a particular area is significant. In the American Society for Training & Development’s benchmarking forum (the more than 200 organizations considered best-practice organizations), data show that more than 50 percent of the content is industry specific, IT systems oriented, and business practices oriented. This underscores the shift in learning content as more organizations focus on technology and job- and industry-specific activities.

For some meetings and events and conferences, content naturally serves as an input objective. For compliance in an ethics program, portions of the content must focus on the regulations themselves. In executive coaching, an objective might require a certain percentage of content focus on business impact.

Project Origin

An often overlooked input objective focuses on why programs are requested in the first place. Too many programs are implemented for the wrong reasons— or at least questionable reasons. Understanding where and how a project originated can provide insight into the reason it was implemented. Table 3.2 shows the tracking of reasons for programs at a large financial services firm. What is revealing in this example is that more than 50 percent of the programs are implemented for questionable reasons (see reasons 1, 2, 4, 10, and 11). By tracking this information over time, executives can see how the origin of projects is changing or should change in the future. Objectives might be based on the desired analysis or reason for the project. For example, in a hospital chain, a request for a sexual harassment prevention program to lower the number of claims had an objective to “proceed with a solution after the cause of excessive claims has been identified.”

Delivery

One of the most interesting and mysterious processes is the way in which a project or program is delivered to an organization. Although strides are being made to transform traditional delivery processes into those that are more technology based, progress has been slower than most experts forecasted. An organization attempting to make dramatic shifts in delivery needs to keep an eye on technological advancement. For learning and development, delivery is shifting from traditional in-person, facilitator-led delivery to e-learning and, more specifically, blended learning.

| Table 3.2: Sources of New Projects and Programs | |

| 1. Management requests it. | 23% |

| 2. The topic is a trend. | 13% |

| 3. An analysis was conducted to determine need. | 12% |

| 4. Other organizations in industry have implemented it. | 11% |

| 5. It supports new equipment, procedures, or technology. | 10% |

| 6. A regulation requires it. | 8% |

| 7. It supports new policies and practices | 6% |

| 8. It supports other processes, such as six sigma, transformation, continuous process improvement, etc. | 6% |

| 9. It appears to be a serious problem. | 5% |

| 10. A best-selling book has been written about it. | 4% |

| 11. Staff members think it is needed. | 2% |

Delivery includes not just the use of technology, but also the efficiency with which the project will be implemented throughout the organization. This is particularly important when a project is implemented on a pilot basis and the results are disseminated throughout the organization. When it comes to creating a new system, procedure, or policy, much of the success hinges on how and when it is implemented throughout the organization. Capturing expectations with objectives is critical to success.

Location

Projects and programs sometimes require particular locations. For example, in the meetings and events industry, an event might call for a particular type of site, or the preference might be the East Coast, West Coast, or a resort. Location can be dictated by whether the project is internal or external. If there is a required location, it is stated as an objective.

Disruption

Disruption of normal work activities almost always presents a concern for project leaders. They often design programs to minimize disruption, which might include setting an objective to ensure that individuals’ regular duties are not affected by participation in the program. For example, a requirement in implementation of a Six Sigma program (a quality improvement process) was that completion of the projects to reach green belt and black belt status should not disrupt normal work activities on the job.

Technology

In most cases, technology is used to coordinate, design, deliver, or manage a project. Sometimes technology should be defined as an input parameter. For example, an objective might require that parts of the project or program be conducted virtually using Microsoft Office Live Meeting. Another objective might require that all participants network with each other through tools such as LinkedIn or IBM’s Lotus Connection. Technology makes a critical contribution to the success of projects and programs. It should be defined upfront with other appropriate objectives.

Outsourcing/Contracting

An increasing number of organizations outsource some or all projects and programs. As an organization moves in this direction, outsourcing objectives might be needed. For example, an objective in the program development stage might require that external contractors develop no more than 50 percent of the program. Internal staff develops the remainder. Another objective might reflect outsourcing of delivery, detailing the percentage of the program delivered by external services compared to internal sources.

HOW TO USE INPUT OBJECTIVES

Input objectives are very basic and clearly define the project from the outset. There are four key issues related to input objectives.

Project Conception

Projects are conceived with input objectives in mind. Whether an initiative grew out of an analysis, a deteriorating problem, or simply an executive request, the process usually includes input objectives. For example, when an executive asks that a project be implemented, that request usually includes input objectives around timing, cost, and scope. When a regulation creates a need for a project, many of the input objectives are defined by the regulation.

When a detailed analysis is completed, the results often reveal the input objectives. The challenge is to ensure that all relevant input items are addressed during the conception stage so that all key stakeholders understand what’s involved.

Project Budgeting

Many input objectives define cost items. One input objective is the actual cost itself. Other input objectives have a tremendous effect on the cost; for example, the technology to be used, the location of the project, and the number of people involved are huge cost items. Even determining the amount of disruption of work allowed has an impact on the cost. Consequently, detail of the input objectives provides a proper backdrop to calculate the overall budget for the project.

Project Planning

As the project is designed, developed, delivered, implemented, and analyzed, the inputs provide the starting point for project planning. They often define who is involved, when they’re involved, and to what extent they’re involved. They also indicate other factors or processes involved in the project. Planning is critical, and input objectives are the beginning of the planning process.

Project Support

Input objectives also provide information to support the project properly. They alert individuals as to what’s needed and when it’s needed. To a certain extent, they also define some of the critical success factors, such as achieving deadlines and budget performance. Many others must support the project, but might not be directly involved. For example, participants’ managers are in a position to influence outcomes significantly. Their support is critical, and the input objectives clearly define who is involved and why they’re involved.

EXAMPLES

Table 3.3 presents a sample of input objectives spread over the topics addressed in this chapter.

| Table 3.3: Examples of Input Objectives | |

| This program must be: | Parameter |

|

Volume/staffing |

|

Volume/staffing |

|

Scope |

|

Scope |

|

Audience/coverage |

|

Audience/coverage |

|

Timing |

|

Timing |

|

Duration |

|

Duration |

|

Budget/costs |

|

Budget/costs |

|

Efficiency |

|

Content |

|

Content |

|

Origin |

|

Origin |

|

Delivery |

|

Location |

|

Location |

|

Disruption |

|

Disruption |

|

Technology |

|

Technology |

|

Outsourcing |

FINAL THOUGHTS

This chapter defines input objectives, the first category of objectives. Though always necessary, they’re often underappreciated and undercommunicated. The more detailed their definition, the better. Input objectives touch on several key elements, including timing, budgeting, scope, duration, coverage, and delivery. From some perspectives, these objectives are obvious and are necessarily defined at the creation of the project; however, too often they stop short of the detail needed. When it comes to objectives, too much detail is rarely a problem.

From the input level, we move to other categories of objectives that define the success of projects or programs. The next chapter focuses on another important set of objectives—reaction objectives.

EXERCISE: WHAT’S WRONG WITH THESE INPUT OBJECTIVES?

This brief exercise will bring the concepts of input objectives into focus. Table 3.4 presents objectives that need improvement. Take a few minutes to examine each objective. What concerns you about each one and how it is stated? Responses to this exercise are provided in Appendix A.

- The project should be completed on schedule.

- The project should be inexpensive and use the latest technology.

- The project should be well received by all stakeholders involved.

- The project will involve all employees with frontline responsibility.

- The project should minimize the disruption of regular work.