CHAPTER 3

Project Quality Planning

Planning is defined in the PMBOK© Guide as “the process in which defining and refining objectives and selecting the best of the alternative courses of action to attain the objectives that the project was undertaken to address are performed.”1 The quality planning stage begins with a commitment and authorization to proceed on a project, and ends with the kick-off meeting of project participants that signals the start of project execution. Quality planning follows quality initiation as the second stage in the five-stage project quality process model shown in Figure 3-1.

As is true of all five stages, the management activities will be much more involved on some projects than on others. Large, complex, unfamiliar projects will require more in-depth planning than smaller, simpler, more familiar projects. The typical quality planning activities required are depicted in the flowchart in Figure 3-2.

Project quality pillars, project activities, and project tools facilitate the movement from the signed authorization to proceed to the point at which all project stakeholders commit to the project plan. Table 3-1 categorizes the project quality pillars, activities, and tools for the quality planning stage into a project factors table.

This chapter is structured to follow the order of the project quality pillars and their sequenced activities shown in Table 3-1. The first number of the listed activities corresponds to the appropriate quality pillar, e.g., Activity 1.1 is associated with the first pillar and Activity 2.1 is associated with the second pillar. The second number refers to the typical approximate chronological sequence of its execution within the pillar’s domain, although this sequential order may well vary with different projects, organizations, or industries. For example, 1.1 Determine Customer Satisfaction Standards normally comes before 1.3 Determine Levels of Decision-Making Authority.

FIRST PROJECT QUALITY PILLAR: CUSTOMER SATISFACTION

As is true in each project stage, several activities relating to customer satisfaction should be completed. Project quality planning begins with a determination of customer satisfaction standards and tradeoff values. If the project sponsor, manager, and core team fully understand these two customer desires, the chances of completing a high-quality project are much greater. The project sponsor, project manager, and core team then need to determine the levels of decision-making authority to avoid strategic confusion and operational conflict.

FIGURE 3-1 Five-Stage Project Quality Process Model

FIGURE 3-2 Project Quality Planning Flowchart

TABLE 3-1 Project Quality Planning Factors Table

| Pillars | Activities | Tools |

| 1. Customer Satisfaction | 1.1 Determine Customer Satisfaction Standards 1.2 Determine Customer Tradeoff Values 1.3 Determine Levels of Decision-Making Authority |

Customer Standards Matrix Customer Tradeoff Values Matrix Project Decision Responsibility Matrix |

| 2. Process Improvement | 2.1 Assess and Prioritize Improvement Needs 2.2 Develop Project Quality Management Plan 2.3 Plan Project Process and Product 2.4 Identify Needed Inputs and Suppliers 2.5 Qualify All Project Processes 2.6 Replan As Needed |

Cause and Efrfect Diagram Benchmarking, Cost/Benefit Analysis JAD Sessions, Concurrent Engineering SIPOC Model Process Quantification Levels |

| 3. Fact-Based Management | 3.1 Identify Data to Collect 3.2 Develop Project Communications Plan 3.3 Collect and Share Project Quality Planning Lessons Learned |

Data and Measurement Matrix PDCA Plus Delta Model |

| 4. Empowered Performance | 4.1 Core Team Commits to Project Plan 4.2 Plan and Conduct Project Kick-Off Meeting 4.3 All Key Stakeholders Commit to Project Plan |

Kick-Off Meeting Agenda and Minutes |

![]()

1.1 Determine Customer Satisfaction Standards

Since the customer ultimately judges the quality of the project output, the project team needs to understand the customer’s standards of satisfaction. The best way to gain this understanding is to ask external and internal customers directly.

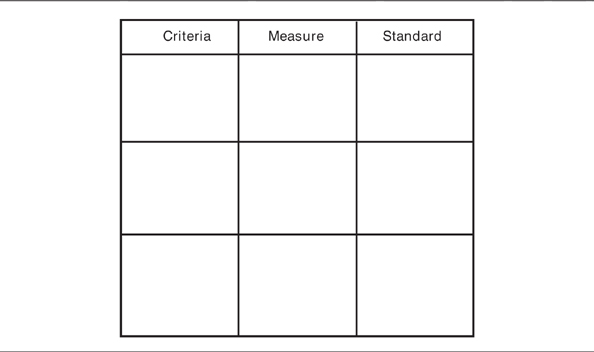

The team then must use this knowledge to develop the specifications for the project output as well as the process steps that will be used to meet the desired standard. The customer standards matrix depicted in Figure 3-3 facilitates this process by providing information in customer criteria for quality project acceptance, methods for measuring criteria compliance, and detailed information on reasonable targets for project quality attainment.

FIGURE 3-3 Customer Standards Matrix

The core team can ask the customer(s) to specify the important criteria upon which they will judge the quality of the project. For each criterion, the customers should then describe how they will measure that criterion and what the standard for satisfaction will be. Quite frequently the customers will not know these standards in advance, so a facilitated discussion with the core team may be necessary. The dimensions of quality in manufacturing and service listed in Chapter 1 may be helpful in getting the customer to determine what criteria are important. This essential step of identifying customer satisfaction standards is frequently left out, and the result is that the project team is left guessing how the customer will judge the quality of the project output. How can someone be confident of producing high-quality output if he or she does not know what the customer wants?

1.2 Determine Customer Tradeoff Values

Customers will have priorities among the various project objectives. The project manager should ask each external and internal customer to prioritize among the project objectives of cost, schedule, quality, scope, contribution to the organization, and contribution to society. Using the project customer tradeoff matrix shown in Figure 3-4, the manager should ask which objectives should be enhanced if possible, which objective(s) must be maintained, and which objectives can be sacrificed if needed.

FIGURE 3-4 Project Customer Tradeoff Matrix

Many customers will not initially be willing to admit that they would consider sacrificing any objective. Therefore, the project manager needs to have a frank discussion to impress upon each customer group that the project team will do its best to achieve all six objectives. However, during the course of the project, decisions will invariably need to be made under unanticipated contingencies, and understanding which objectives are relatively more important will help the project manager make the kind of decisions that the majority of customers will likely accept.

The project manager and sponsor must also decide which customer groups are relatively more important if priorities conflict. Typically, external paying customers and top management are considered quite important. If significant differences in priorities surface among various customer groups, more consideration may be necessary at this point.

Additionally, the project team should consider possible preplanned product improvements—particularly if the sponsor or a majority of customers choose to enhance performance. In any event, if the project team starts thinking about product and process improvements early, both current and future projects are likely to benefit. The objectives selected for enhancement by the customers (cost, schedule, quality, scope, contribution to the organization, and/or contribution to society) should direct the team’s thinking as the members continually strive for improvement.

1.3 Determine Levels of Decision-making Authority

One frequent cause of quality problems is that project participants do not know who is allowed to make certain decisions. This problem can be minimized if the proper decision-makers have the time, information, and skill to make decisions and understand their respective roles. The project decision responsibility matrix in Figure 3-5 is a tool for clarifying three decision-making factors relating to specific issues: (1) who must be informed, (2) who is authorized to make recommendations, and (3) who is authorized to decide.

For each issue that must be decided, responsibility for making the recommendations and being informed should be noted. A recommended approach is to have one primary decision-maker per issue (others may recommend), with the project manager at least informed about virtually every issue. While all project participants have roles, the project manager is ultimately responsible for quality and must know what is happening.

FIGURE 3-5 Project Decision Responsibility Matrix

SECOND PROJECT QUALITY PILLAR: PROCESS IMPROVEMENT

Carpenters are told to measure twice and cut once to avoid making mistakes. Likewise, project managers are encouraged to put extra effort into planning their work processes to avoid quality problems later. Many process-related issues should be settled during the project quality planning stage.

An initial assessment and prioritization of process improvement needs based on root cause analysis are necessary to determine whether and to what extent incremental improvement, competitive parity, or breakthrough dominance are warranted with different processes. Then, a quality management plan needs to be developed to comprehensively address the diagnosed problems and opportunities. Next, both the process and the product of the project should be planned simultaneously. The customer value supply chain needs to be identified, along with the inputs each will provide. All processes need to be qualified. Finally, planning is iterative and a great deal of replanning typically is needed. Good process planning goes a long way toward good project quality.

2.1 Assess and Prioritize Process Improvement Needs

When assessing a process, one of the most important things to understand is the process variation. Variation is often the reason for poor quality. The project manager needs to understand not only what kind of variation exists, but also what the causes are of that variation. Armed with this knowledge, a smart manager can reduce or eliminate the problem variation.

Variation in project process output and other problems can occur for many reasons, including materials, machines, methods, people, measurement, and environment. The first goal of project process improvement is a correct diagnosis of the root causes of problems and a relative ranking of their severity or urgency for prioritized attention. Otherwise, project managers can end up treating symptoms rather than causes and attacking marginal rather than critical causes.

The cause-and-effect diagram (or fishbone diagram) in Figure 3-6 provides one way to identify process problems, their root causes, and their contributory causes. The fishbone diagram is constructed so that the fish head shows the problem, each major branch (machines) pointing into the main stem represents a possible cause, and minor branches (defective parts) pointing into the major branches are contributors to the cause of the process problem. The diagram, therefore, identifies the most likely causes of process problems so that project participants are properly focused to collect and analyze relevant data to prove which of the possible causes are actual causes.

FIGURE 3-6 Cause and Effect Diagram

In addition, the involvement of the project team and other customers in the brainstorming input into this causal analysis usually heightens their awareness of problem causes and their sense of commitment to resolutions. Other tools such as regression analysis and statistical correlation analysis will identify positive, negative, or neutral correlations between and among the variables.

Among the key factors in this step is determining what type of improvement is sought for each project work process. Given different issues with different priorities, the project team must decide whether proposed resolutions will aim at incremental improvement, competitive parity, or breakthrough dominance. The team also needs to determine which process improvements should come first.

2.2 Develop Project Quality Management Plan

After assessing and prioritizing the process improvement needs, the quality management plan is developed. This master plan links all prioritized process needs and resource requirements to strategic priorities and ensures that all project participants have clear goals and delineated responsibilities. All process and product standards are framed in concrete, measurable terms through operational definitions such as time deadlines, budgetary cost limits, and product tolerance specifications. Tentative fund allocation decisions are displayed and procedures for plan review and alteration are specified. The project quality management plan answers the questions:

Where and why are they strategically prioritized?

When are they scheduled to begin and end?

How (in terms of timelined process steps and detailed procedures to meet standards) will they be tracked and executed?

Who is responsible for performing work during each phase of each project and for sharing information?

How many resources (financial and non-financial) are required?

In addition, the plan requires emergent feedback loops so that operations in the field can provide corrective information while the plan is being deployed and reformulated.

In developing this master plan, the project management team relies on internal and external benchmarking of products/services and processes. Longitudinal data and trends of prior internal organizational performance standards (along with horizontal comparative data and trends from external sources) ensure that the master plan has the necessary benchmark information to enact competitive parity or breakthrough dominance improvements based on factual input.

Process benchmarking, for example, starts with identifying specific processes that the team wants to improve. Next, the project team identifies an organization that is particularly strong in that process. Then, the project manager contacts a manager at the organization against which he or she wants to benchmark. The project team prepares focused process questions in advance and someone from the project team makes a site visit to observe the process in action and interview key employees. The project team then analyzes the data by identifying gaps between what they are presently capable of doing and what the benchmark organization is doing. Finally, the team decides what aspects of the benchmarked process they can use as is in their project, what must be adapted for the project, and what is not relevant or achievable at this time.

Once the project team has finished benchmarking, they can also use cost/benefit analysis to determine if a proposed approach makes economic sense. The cost/benefit analysis should consider the operating conditions and other environmental factors that the user of the project deliverables will experience.

2.3 Plan Project Process and Product

Now that process improvement needs are prioritized and a quality management plan is developed, it is time to jointly plan project products and the work processes that are needed to create them. For planning project processes and products effectively in a quality manner, two tools are useful: joint application design sessions and concurrent engineering.

A joint application design (JAD) session is used to ensure that all customer desires are identified and prioritized, as well as to develop the technical approach, estimate the time required to develop the technical approach, and estimate the time required to develop each prioritized project feature. Prototypes are sometimes used in JAD sessions with the users to refine the requirements and to identify missing functionality. This step is used when customers lack experience and need concrete examples to extract business requirements.

A JAD session consists of two parts. During the first part of the JAD session, the customers identify possible enhancements and prioritize each while developers achieve enough understanding of the functional requirements that they can (during the second part of the JAD session) estimate the time required. The first part of the JAD session starts with the facilitator reading each potential enhancement aloud. For the enhancements that have long descriptions, the facilitator encourages a knowledgeable participant to paraphrase the description. Once the description is read or paraphrased, five questions are answered for each feature and eventually prioritized:

What do we not understand about this request?

What is the business reason for this request?

What is the impact of not doing this enhancement?

What action items need to be accomplished?

What impact does this have on other parts of the project?

During the second portion of the JAD session, only the developers go through the proposal features. For each feature, the project manager identifies who must estimate the time required. If individuals need additional information, probable estimates are presented until more information is obtained. People must have enough time to envision how much work is involved without getting trapped into detailed development discussions.

The other useful tool in project product and process improvement is concurrent engineering. Concurrent engineering is a process in which all key project participants involved in bringing a product/service to market are continuously involved with that product/service development from conception through sales. This simultaneous rather than sequential process shortens product development cycles, lowers costs, reduces rework, and generally addresses quality issues at an early stage.

Project teams that take the time to simultaneously plan both the project outputs and the processes to create them greatly lessen the chances of unpleasant surprises (quality problems) later.

2.4 Identify Needed Inputs and Suppliers

Now that the processes needed to produce the project output are understood, it is time to identify the inputs that are needed. In addition to the house of quality, the supplier-input-process-output-customer (SIPOC) model is a tool that can be used to improve the project process by clearly identifying relationships among suppliers, inputs, processes, outputs, and customers. An example is shown in Figure 3-7.

The SIPOC is a visual guide to help a project team work backwards from customers to identify all the project customers (C), including unintended stakeholders who are impacted by the project. The SIPOC next guides the team in identifying what product, service, and information outputs (O) each customer wants to receive (or receives inadvertently) and the satisfaction standards that customers demand from each output of the project. The third item the team uses the SIPOC to identify is the set of process (P) actions the project team needs to take and the standards that must be set in order to create those identified outputs. Flowcharts, introduced in Chapter 2, are often used to illustrate this process portion of a SIPOC.

The fourth item that teams use the SIPOC to identify is the set of information, workers, material, or other inputs (I) needed to meet the process standards. Finally, the SIPOC guides the team in identifying the suppliers (S) of the desired inputs. A list of quality suppliers can then be generated to sustain long-term quality improvement partnerships with solid domestic and global suppliers.

2.5 Qualify All Project Processes

Organizations that produce excellent quality outputs insist on using excellent processes to produce their outputs. One method of ensuring that only excellent processes are used is to qualify each process. Process qualification levels from spontaneous to optimized status have already been addressed in Chapter 1. However, once strategic alignment and process improvement priorities have been decided, the ongoing qualification of all project processes will determine the rate of efficiency and effectiveness improvement over the course of the project.

FIGURE 3-7 Supplier-Input-Process-Output-Customer (SIPOC) Model

2.6 Replan As Needed

Since the master plan requires ongoing feedback from project implementers, the likelihood for replanning is high. The master plan provides for three feedback channels:

Outside to inside

Inside from top to bottom

Inside from bottom to top.

The openness to feedback during project formulation and implementation from the outside (customers and others) allows external benchmarking data and external stakeholder voices to have an impact on project replanning. The top to bottom feedback is customary in hierarchical organizations. Feedback from bottom to top allows all participants to have a voice often and uses information technology. An example is project operators using laptops to e-mail replanning suggestions to the project manager, sponsor, or even CEO. The more sources of feedback that are considered, generally the better the replanning effort becomes. Prudent project managers and teams learn how to sort though vast quantities of data to quickly find the most useful information for their replanning.

THIRD PROJECT QUALITY PILLAR: FACT-BASED MANAGEMENT

While all the project planning and replanning are occurring, several issues concerning data must be resolved. The team needs to identify the data that must be collected, develop a project communications plan, and capture lessons learned for project participants.

3.1 Identify Data to Collect

A fundamental part of making fact-based decisions is gathering data that can be compiled and interpreted into the facts needed to make sound project decisions. The science of determining what data to collect, how to define the data, how to collect the data, how to analyze the data, and how to use the data in decision-making is called metrics. In an effective metrics system:

Normal variation is distinguished from abnormal variation

All project stakeholders have a common understanding of project status

Metrics are practical and easy to obtain

Metrics are collected at regular intervals

Management accepts metrics.

The SIPOC model is a useful starting place to determine some of the needed metrics, such as customer satisfaction standards (see Figure 3-7). This can be used both for identifying measures to collect and for setting goals. Projects are conducted either within one company or among multiple companies. In either event, the project metrics need to align with those of the parent organization and any other organizations involved.

Another tool that can be used to determine what data needs to be collected is the data and measurement matrix, shown in Figure 3-8. While this simple tool can be used to help determine what needs to be collected with regard to cost, schedule, scope, and quality, the emphasis here is on quality. The project team (often in conjunction with the customer) determines the various quality factors (such as errors in a software project) that need to be monitored. Once the quality factors have been identified, the team needs to state clearly what data are needed to indicate the level of expected quality (such as how many errors one could expect at each project checkpoint if the project is proceeding according to plan). Then the team needs to determine what data will be collected to determine the actual status of each quality factor. Finally, the team should determine the monitoring activities—who will collect the data and how.

3.2 Develop Project Communications Plan

A major source of quality problems on projects is faulty communications. Keeping all project participants accurately informed leverages the firm’s resources and sustains momentum. To decrease the likelihood of making mistakes, it is imperative for a project core team to develop a comprehensive project communications plan—and to use it. Most people receive far more communications than they need, so the answer is not more information, but more useful, specific information.

Project communications is an excellent opportunity to use the PDCA model (see Figure 2-4). The project core team first plans (Plan) who needs to know what information, how often they need it, and their preferred information format. Next, the team uses (Do) the communications plan. Very quickly and repeatedly, the team should seek feedback (Check) on the quality and completeness of the information being transmitted through the communications plan, using information technology wherever feasible. Finally, the team should Act upon the feedback by improving the communications plan.

FIGURE 3-8 Data and Measurement Matrix

3.3 Collect and Share Project Quality Planning Stage Lessons Learned

Periodically throughout the project—at least at the end of each stage—lessons learned should be captured to help conduct future stages better. The plus delta tool can be used for collecting the lessons learned at the end of the planning stage. Lessons learned should then be used to improve future stages of the current project and other projects, and through sharing, contribute to the organization’s learning capacity.

FOURTH PROJECT QUALITY PILLAR: EMPOWERED PERFORMANCE

All four project quality pillars are important. The first three (customer satisfaction, process improvement, and fact-based management) reinforce and are supported by the fourth (empowered performance). In other words, doing a good job on the first three helps empower individual performance, and outstanding individual performance through empowerment really drives successful accomplishment of the other three pillars.

The determinants of empowered performance that must be achieved at the end of the project quality planning stage are the commitments of the core team and all project stakeholders to accept the detailed project plan. Once the core team members review the entire plan and determine that they want to commit to it, they will informally sell the project plan to the diverse project stakeholders. Nevertheless, a formal project kick-off meeting is a useful public ritual to answer organizational concern and to solidify organizational support.

4.1 Core Team Commits to Project Plan

Empowered performance will not energize the project unless and until the core team commits to the project plan. If the team members believe that improvements are needed in the project plan, this is the time to make them. There will always be replanning, both to elaborate with more details and to respond to customer changes or other changing conditions. Nevertheless, the core team members and the project manager must each personally commit to the detailed project plan before they can convince the sponsor, customers, and other stakeholders to commit. Many wise sponsors have approved project plans that they felt were less than ideal because the project manager and the core team were so passionately committed. The sponsor’s trust in such situations is usually rewarded because the team finds ways to overcome obstacles.

While we prefer excellence in everything, we would rather have a good plan and a passionate team than an excellent plan and a compliant team. One note of caution: Even the most committed team cannot usually overcome a seriously flawed plan. All participants need to use good judgment along with their enthusiasm.

4.2 Plan and Conduct the Project Kick-Off Meeting

The kick-off meeting serves to transition from planning the project to executing it. The core team that has performed much of the planning now shares with all the people who will perform the project work, including suppliers, ad-hoc workers, etc. The project work should be described in broad terms and then the participants should have the opportunity to ask as many questions as they like.

The PDCA model (shown previously in Figure 2-4) can be used to study and improve the kick-off meeting process just as it can be used to improve many other work processes.

The “Plan” step includes reviewing the project charter, considering carefully who needs to attend (maybe some participants only need to attend a portion of the meeting), and creating a detailed agenda for the kick-off meeting. (See Figure 3-9 for an example of a kick-off meeting agenda.)

The “Do” step is conducting the kick-off meeting. There are three types of goals for the kick-off meeting participants: building relationships, understanding tasks, and learning. The typical kick-off meeting has a structured order and starts with a quick review of the agenda (asking whether anything should be modified). Topics are covered one at a time. The core team member who was assigned the task of presenting a topic will do so, recommending an approach, and the core team members will answer questions until a collective decision is reached. Finally, as the meeting comes to a close, the project manger will summarize decisions made and assign action items for each participant.

The “Check” step incorporates the meeting evaluation stage. The last item on the agenda for meetings should be an evaluation. The plus delta model shown previously in Figure 2-6 is a useful technique for improving meetings of any kind.

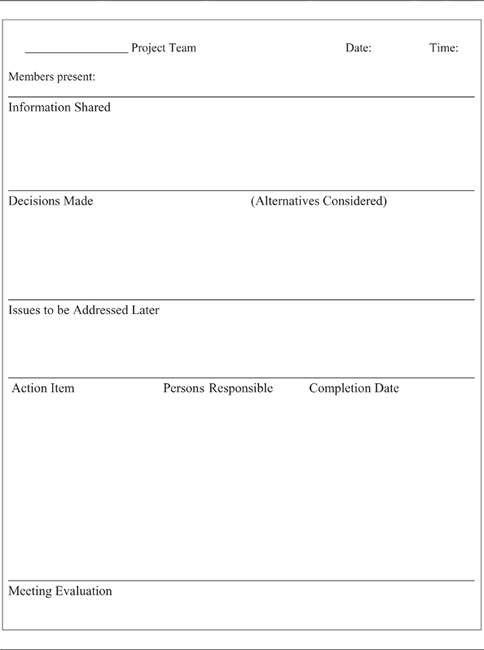

The “Act” step is following up on all the decisions made in the kick-off meeting and striving to improve future performance on both current and future projects. To ensure that all agreed-upon tasks are completed, good meeting minutes should be written up and distributed promptly so participants can create their detailed project plans. (See Figure 3-10 for an example of a kick-off meeting minutes template.)

4.3 All Key Project Stakeholders Commit to Project Plan

To increase the likelihood of commitment by all key project stakeholders, it is helpful to anticipate and have detailed answers to the following questions:

Why this project?

Why now?

Are financial resources adequate?

Are human resources adequate?

How likely is it that customer requirements will change?

How often and by how much will they change?

Are appropriate data identified?

Is the data gathering and analysis system adequate?

Have customer rights been described?

Are standards identified or developed by which the project will be judged?

Are both deliverables and work processes to create them as simple as practical?

How does the rest of the organization benefit from this project’s success?

How does society benefit from this project’s success?

FIGURE 3-9 Project Kick-Off Meeting Agenda

It is also helpful to share the plan (or portions of it) with many of the other (non-key) stakeholders who could potentially disrupt the project. The project manager, sponsor, and core team should consider who might be an ally to the project if courted and who could become an enemy if not courted. Then they should develop and execute a strategy of trying to win over the various groups.

FIGURE 3-10 Kick-Off Meeting Minutes Template

Often, a particular stakeholder is interested primarily in only one small aspect of the project. When that is the case, sharing why the project is important and showing a willingness to make adjustments (if practical) can help a minor stakeholder become less negative about the project. An ongoing dialogue may be necessary throughout the project with many diverse stakeholder groups. Nevertheless, project quality planning is complete when all key project stakeholders have agreed to the project plan.

NOTES

1. Project Management Institute Standards Committee, A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK© Guide) (Upper Darby, PA: Project Management Institute, 2000), p. 30.