Wireless Threats

Wireless threats come in all shapes and sizes, from someone attaching to your Wireless Access Point (WAP) without authorization, to grabbing packets out of the air and decoding them via a packet sniffer. Many wireless users have no idea what kinds of danger they face merely by attaching a WAP to their wired network. This section discusses the most common threats faced by adding a wireless component to your network.

The airborne nature of WLAN transmission opens your network to intruders and attacks that can come from any direction. WLAN traffic travels over radio waves that the walls of a building cannot completely constrain. Although employees might enjoy working on their laptops from a grassy spot outside the building, intruders and would-be hackers can potentially access the network from the parking lot or across the street using the Pringles can antenna (refer to Figure 10-5).

Sniffing to Eavesdrop and Intercept Data

Because wireless communication is broadcast over radio waves, eavesdroppers who merely listen to the wireless transmissions can easily pick up unencrypted messages. Unlike wire-based LANs, the wireless LAN user is not restricted to the physical area of a company or to a single WAP.

The range of a wireless LAN can extend far outside the physical boundaries of the office or building, thereby permitting unauthorized users access from a public location such as a parking lot or adjacent office suite. An attacker targeting an unprotected AP needs only to be in the vicinity of the target and no longer requires specialized skills to break into a network. Any time I do a network assessment for a customer in a shared office building, I almost always find

• A neighboring business that has an open wireless network

• A neighboring user that has joined my customer’s wireless network

• One of my customer’s employees using their neighbor’s wireless

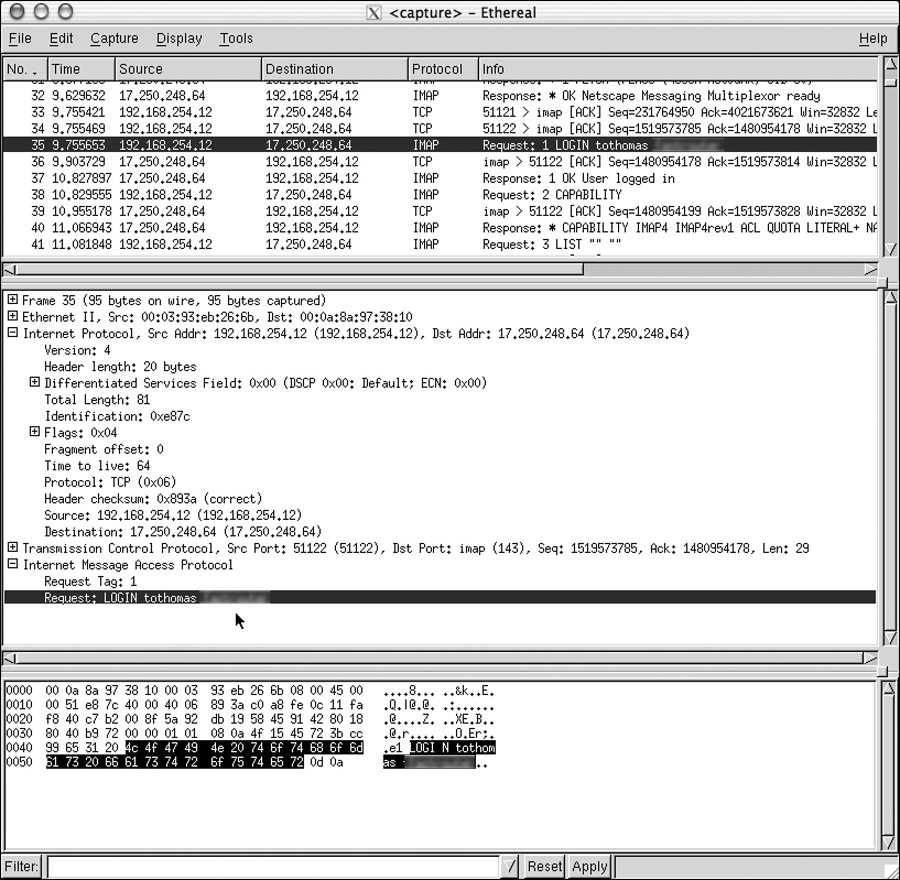

If you want to examine the traffic going out over an Ethernet connection (wired or wireless), the best tool that comes to mind is the ubiquitous packet sniffer application. Packet sniffers enable the capture of all the packets going out over a single or multiple Ethernet connection for later inspection. These sniffer applications grab the packet, analyze it, and reveal the data payload contained within. The theft of an authorized user’s identity poses one the greatest threats. Figure 10-6 shows a freeware packet sniffer known as Ethereal, which is used on an Apple MacBook Pro over a wireless Ethernet network to capture a mail application transmitting a username and password. (Names and passwords have been changed to protect the innocent, of course.)

Figure 10-6 Wireless Sniffer Packet Capture

The intent here is to show you how packet sniffers can be used against known behavior. In this case, when users start their computers, one of the first things they do is check email. Many email servers do not require any sort of encryption and, because the wireless network is not transmitting anything encrypted, the data is sent in clear text. Attackers with a packet sniffer could now steal the user identity and log in to the mail server as the unaware user anytime because they literally pulled the password out of the air.

If you have read through packet captures before and are familiar with the information they contain, you should have immediately recoiled in horror at the knowledge that wireless networks are sniffers readily available, and several are free. If this is the first time you have seen a packet capture, you might be in for a shock as you find out the wealth of information contained in a packet’s data payload. Imagine if you were a domain administrator logging in to the domain and checking your online bank account or other information that could be critically damaging if someone hijacked it.

Denial-of-Service Attacks

Potential attackers who cannot gain access to your wireless LAN can nonetheless pose security threats by jamming or flooding your wireless network with static noise that causes wireless signals to collide and produce CRC errors. Wireless networks are especially vulnerable to these sorts of attacks, sometimes even unintentionally as every wireless network shares the same unlicensed frequencies (channels). These denial-of-service (DoS) attacks effectively shut down or severely slow down the wireless network in a similar way that DoS attacks affect wired networks. Sometimes a DoS is not malicious; it could be a wireless phone that is set on the same frequency causing interference or a microwave oven. Sometimes, though, it could be phony messages to disconnect users or consume AP resources.

This vulnerability is apparent, and being on a wired network does not reduce your vulnerability to viruses, attacks, or in any other way increase security; it will quite likely get worse. However, newer wireless standards such as 802.11n use the 5 GHz frequency, which is a larger range of channels and less crowded, reducing the chance of accidental service interruptions due to channel overlap.

Note

Restaurants, hotels, business centers, apartment complexes, and individuals often provide wireless access with little or no protection. In these situations, you can access other computers connected to a wireless LAN, thereby creating the potential for unauthorized information disclosure, resource hijacking, and the introduction of backdoors to those systems. When users take corporate laptops home and use them on wireless networks, the vulnerabilities to your network increase. I have been on network assessments reviewing wireless usage and found that many a CEO, CFO, or CTO has the IT staff set up a wireless device at home for them with the same characteristics they have at work (SSID and so on). This makes it easy for them to work at home with no trouble; however, the corporate network is extremely vulnerable because an attacker can go after a corporate employee’s home network and compromise his machine. When the employee goes to work, so does the attacker—now he is inside your corporate network. Common sense is needed here—and a commitment by everyone in the organization’s management team to secure the network. This means not mixing corporate and home security regardless of how much fussing that C level may do; security is bigger than the individual.

Perhaps a bit more common is when other wireless devices unintentionally cause a DoS to your wireless data network—for example, that new cordless phone running on 2.4 GHz, or placement of APs near devices that generate interference and affect their operation, such as microwaves. Not all reduction in wireless connectivity is related to attackers, so remember that wireless networks are based on radio signals, and many things (walls, weather, and wickedness) can affect them.

Rogue/Unauthorized Access Points

Wireless APs can be easily deployed by anyone with access to a network connection, anywhere within a corporation or business. Most wireless deployments are in the home, so people with laptops can use them in any room in the house. The ease with which wireless technologies can be deployed should be a concern to all network administrators.

Because a simple WLAN can easily be installed by attaching a WAP (often for less than $100) to a wired network and a wireless enabled laptop, employees are deploying unauthorized WLANs while IT departments are stuck trying to track down these rogues. Unauthorized WAPS are known more commonly as rogue APs.

An executive of a large technology conglomerate was recently quoted as saying something like, “The hardest network to secure against wireless threats was one that had no wireless access at all.” What this executive meant was that just because a company did not buy and install any wireless gear on its network did not mean that there wasn’t any.

The concept behind wireless technology is to give people the freedom to roam around and still be connected to their network resources. The lure of this freedom is just too tempting to some folks in corporate America, so they go out and buy wireless gear on their own and hook it up to the office network. Now, you begin to see the problem.

If you can imagine how difficult it is to prevent people from bringing software from home and installing it on their work machines, it is ten times more difficult to prevent power users from “self-adopting” wireless gear into the office LAN.

You might ask, “What is the harm in doing this?” The harm is that by installing an unauthorized AP, you have now extended an invitation to every person within its signal radius to prowl your company’s network, files, Internet access, printers, and any other devices currently connected to the private corporate network.

Your network administrators take great pains to protect the corporate network from attackers and other evildoers, and now there is a completely unprotected conduit into the company’s holiest of holies: your internal corporate network.

A well-documented company has several security policies in place that govern every type of behavior when a user connects to the network. Rogue APs subvert these policies and open the doors to all varieties of bad things happening to the network.

To be perfectly fair to the employees who might commit this wireless breach of security, it is important that the following information be made abundantly clear:

• Only authorized IT staff is allowed to connect networking equipment.

• All devices that connect to the network, especially wireless APs, must conform to established security policies.

• Any devices that have been installed by anyone other than approved IT staff will become either the property of the company or will be rendered inert (that is, smashed into a million pieces).

• Hackers install rogue APs on a company network with the intention of stealing secrets and damaging data; this means no holiday bonuses because this kind of damage can cause a company to go out of business.

Finding rogue APs has become a little easier than in the past through the use of freely available software; the section titled “NetStumbler” delves into this. This same piece of software that made life easier for hackers has now become the favored tool of network security specialists for dealing with unauthorized wireless access points.

Misconfiguration and Bad Behavior

Wireless APs are typically centrally managed in today’s enterprise networks; however, they are slow in catching up with technology. The latest version of 802.11 has evolved to include many new features that have resulted in relatively complex configuration options. Add to this the inherent capability of laptops to create ad-hoc networks via peer-to-peer technologies. The latest versions of Windows operating systems have removed the complexity involved with ad-hoc wireless networking, bypassing network security procedures automatically.

AP Deployment Guidelines

I was going to call these “the rules for attackers to deploy rogue access points,” but applying rules to those with criminal intent seemed an oxymoron. Attackers have developed some best practices that they have shared in their community because many wireless networks are relatively easy to break into. It is important that any wireless deployment use effective and efficient wireless security techniques and policies. In addition to using the best encryption and practices defined in this chapter, wireless intrusion prevention systems (WIPS) and wireless intrusion detection systems (WIDS) are commonly used to verify and protect the integrity of wireless networks. Following is a brief list of what you can do to prevent attackers from “casing the joint”:

• Know what you are trying to gain before placing the access point.

• Plan for the use of the AP; this means place it so that if you have your laptop out and working, you do not look suspicious.

• Place the AP as discretely as possible while maximizing your ability to connect to it.

• Disable SSID broadcasting, thus requiring the target’s IT staff to have a wireless sniffer to detect it.

• Disable all network management features of the AP, such as SNMP, HTTP, and Telnet.

• If possible, protect the AP’s MAC address from appearing in ARP tables.

The obvious disclaimer here is that these actions are not something you should ever do without—and I really stress this—written permission. Many companies view even the accidental connection to their wireless network as an attack, so it is likely that you are going to be viewed as guilty until you prove your innocence.

It is also important to note that devices designed to jam radio signals have been around since before wireless ever became a standard. Because wireless is a radio frequency, it can be easily jammed with a simple transmitter purchased online.

Wireless Security

You might be wondering why someone would want to use a wireless connection with all the insecurities that seem to go along with it. All is not lost, thanks to the focus that has been placed on securing wireless networks.

From its inception, the 802.11 standard was not meant to contain a comprehensive set of enterprise-level security tools. Still, the standard includes some basic security measures that can be employed to help make a network more secure. With each security feature, the potential exists for making the network either more secure or more open to attack.

Working on the layered defense concept, the following sections look first at how a wireless device connects to an AP and how you can apply security at the first possible point.

Service Set Identifier (SSID)

By default, the AP broadcasts the SSID every few seconds in beacon frames. Although this makes it easy for authorized users to find the correct network, it also makes it easy for unauthorized users to find the network name. This feature is what enables most wireless network detection software to find networks without having the SSID upfront.

SSID settings on your network should be considered the first level of security and should be treated as such. In its standards-adherent state, SSID might not offer any protection against who gains access to your network, but configuring your SSID to something not easily guessable can make it more difficult for intruders to know what exactly they are seeing.

Finding nearby SSIDs, even if they are not broadcasting, is relatively easy. One of my favorite tools is from a wireless company known as Meraki. It offers an online web browser-based Wi-Fi Stumbler that will find nearby SSIDs, as shown in Figure 10-7. If you look, you can see that several of those listed are running WEP, which, as we have discussed, is foolish. This tool also provides helpful information such as channel, signal strength, and radio manufacturer/type. As a network administrator, this is extremely helpful and extremely convenient; I especially like the “I wish this page would” feature... now that is customer support!

A complete listing of manufacturers’ SSIDs and even other networking equipment default passwords can be found at www.cirt.net/.

Device and Access Point Association

Before any other communications take place between a wireless client and a wireless AP, the two must first begin a dialogue. This process is known as associating. When 802.11b was designed, the IEEE added a feature to enable wireless networks to require authentication immediately after a client device associates with the AP, but before the AP transmission occurs. The goal of this requirement was to add another layer of security. This authentication can be set to either shared key authentication or open key authentication.

You must use open key authentication because shared key is flawed; although that is counterintuitive, this recommendation is based on the understanding that other encryption will be used. Wireless network administrators need to be aware that accidental or malicious association is a risk that needs to be managed. A user turns on his laptop and unknowingly associates with a neighboring organization’s wireless network; the user might not even be aware this has occurred. Malicious association is when a hacker uses this accidental association to gain access to your network by taking over a client and planting a tool to enable him to gain deeper access.

Wired Equivalent Privacy (WEP)

There is a lot of misconception surrounding WEP, so let’s clear that up right away. WEP is not, nor was it ever meant to be, a security algorithm. WEP was never designed to protect your data. WEP is not designed to repel attackers; it simply makes sure that you do not transmit everything in clear text. The problem occurs when people see the word encryption and make assumptions. WEP is designed to make up for the lack of security in wireless transmission, compared to wired transmission; however, it should never be used to secure your wireless networks.

WEP Limitations and Weaknesses

WEP protects the wireless traffic by combining the “secret” WEP key with a 24-bit number (Initialization Vector, or IV), randomly generated, to provide encryption services. The 24-bit IV is combined with either the 40-bit or 104-bit WEP passphrase to give you a possible full 128 bits of encryption strength and protection—or does it? There are a few issues surrounding the flawed current implementation of WEP:

• WEP’s first weakness is the straightforward numerical limitation of the 24-bit Initialization Vector (IV), which results in 16,777,216 (224) possible values. This might seem large, but you know from discussions in Chapter 6 that this number is deceiving. The problem with this small number is that eventually the values and thus the keys start repeating themselves; this is how attackers can crack the WEP key.

• The second weakness is that of the possible 16 million values, not all of them are good. For example, the number 1 would not be very good. If an attacker can use a tool to find the weak IV values, the WEP can be cracked.

• WEP’s third weakness is the difference between the 64-bit and 128-bit encryption. Perception would indicate that the 128 bit should be twice as secure, right? Wrong. Both levels still use the same 24-bit IV, which has inherent weaknesses. Therefore, if you think going to 12 bit is more secure, in reality, you will gain absolutely no increase in the security of your network.

Of course, freely available tools can accomplish all these things and are ready for the attackers to download and use as discussed in the section “Essentials First: Wireless Hacking Tools,” later in the chapter. Using WEP is not advised, and if you run across a network running WEP, buy them a copy of this book, and point out this chapter to them for me!

MAC Address Filtering

MAC address filtering is another poor and unsuccessful way people have tried to secure their networks over and above the 802.11b standards. A network card’s MAC address is a 12-digit hexadecimal number that is unique to every network card in the world. Because each wireless Ethernet card has its own individual MAC address, if you limit access to the AP to only those MAC addresses of authorized devices, you can easily shut out everyone who should not be on your network.

However, MAC address filtering is not completely secure and, if you rely solely upon it, you will have a false sense of security. Consider the following:

• Someone must keep a database of the MAC address of every wireless device in your network. If there are only 10–20 devices, it is not a problem. However, if you must keep track of hundreds of MAC addresses, this quickly becomes a management nightmare.

• MAC addresses can be changed, so a determined attacker can use a wireless sniffer to figure out a MAC address that is allowed through and set his PC to match it to consider it valid. Note that encryption takes place at about Layer 2, so MAC addresses will still be visible to a packet sniffer.

If you are thinking of using MAC address filtering as your sole means of security, that is a bad idea because it provides a false sense of security and prevents only unintended connections, not a directed attack. This form of wireless security should be used only with one of the methods covered in the following sections.