CHAPTER EIGHTEEN

PROSODY:

STRUCTURE AS FILM SCORE

Now that you have some tools for manipulating common meter and matched couplets, let's take a closer look at the power you have at your fingertips when you use your tools effectively. Look at this lyric, “Can't Be Really Gone” by Gary Burr (recorded by Tim McGraw):

Her hat is hanging by the door

The one she bought in Mexico

It blocked the wind and stopped the rain

She'd never leave that one

So she can't be really gone

The shoes she bought on Christmas Eve

She laughed and said they called her name

It's like they're waiting in the hall

For her to slip them on

So, she can't be really gone

I don't know when she'll come back

She must intend to come back

And I've seen the error of my ways

Don't waste the tears on me

What more proof do you need

Just look around the room

So much of her remains

Her book is lying on the bed

The two of hearts to mark her page

Now, who could ever walk away

With so much left undone

So, she can't be really gone

No, she can't be really gone

Okay. How soon did you know that she isn't coming back?

Right. At the end of the first verse. Of course, that's only because we're smart, intuitive beings — we just know these things. Poor guy. He has no idea. While this poor slob is looking for reasons to prove that she's coming back, we, with our deeper understanding of life and the ways of the world, know the real truth.

Kinda like watching a movie where the beautiful couple is running in slow motion toward each other through a golden sunlit field, smiling. There's a soft lens. The film score is full of romantic strings, swelling in a major key. But as they float closer to each other and our chests swell in anticipation of the long-awaited embrace, an oboe cuts through the film score in a nasty minor second, and our bodies stiff en a little. We don't really notice the music, but something tells us that something bad is about to happen. Suddenly, the guys with the shotguns leap up from their hiding places and blow the couple away. We knew it! We knew something bad was going to happen! Of course, that's because we're smart, intuitive beings — we just know these things.

Of course, the film score, which is created to stand behind the action, gave it away. Most folks don't really notice it — they just react. The composer is pulling the strings and we, like puppets, react predictably, feeling just what the score makes us feel.

That's what's going on in “Can't Be Really Gone,” but this time it's not the music that creates the film score. It's the structure of the lyric, acting, just like a film score, on our emotions.

Look at the first verse:

Her hat is hanging by the door

The one she bought in Mexico

It blocked the wind and stopped the rain

She'd never leave that one

So she can't be really gone

Though the character is giving us evidence that she's not gone for good, we don't believe him. Something just doesn't feel right. The verse itself feels funny — unstable.

PROSODY

Aristotle said that every great work of art contains the same feature: unity. Everything in the work belongs — it all works to support every other element. Another word for unity is prosody, which is the “appropriate relationship between elements, whatever they may be.” Some examples of prosody in songs might be:

-

Between words and music: A minor key could support or even create a feeling of sadness in an idea.

-

Between syllables and notes: An appropriate relationship between stressed syllables and stressed notes is a really big deal in songwriting — when they are lined up properly, the shape of the melody matches the natural shape of the language.

-

Between rhythm and meaning: Obvious examples like “you gotta stop! … (pause) … look and listen” or writing a song about galloping horses in a triplet feel.

The elements all join together to support the central intent, idea, and emotion of the work. Everything fits. Prosody: the appropriate relationship between elements.

Stable vs. Unstable

Looking at your sections through the lens of stablility or instability is a practical tool for creating prosody because you'll be able to use it for every aspect of your song: the idea, the melody, the rhythm, the chords, the lyric structure — everything. It governs the choices you make. Ask yourself: Is the emotion in this section stable or unstable? Once you answer that question, you have a standard for making all your other choices.

The Five Elements of Structure

Every section of every lyric you write uses five elements — always the same five elements — of structure. These elements conspire to act like a film score and, in and of themselves, create motion. And motion always creates emotion, completely independent of what is being said. Ideally, structure should create prosody — support what is being said — strengthening the message, making it more powerful.

The five elements of lyric structure are:

-

number of lines

-

length of lines

-

rhythm of lines

-

rhyme scheme

-

rhyme type

In “Can't Be Really Gone,” we'll look at the prosody — the relationship between its structure and its meaning. Let's take a look at each of these five elements and what they do in the first verse.

1. Number of Lines

Every section you'll ever write — verses, choruses, pre-choruses, bridges — will have (here it comes, get ready) some number of lines or other. Okay, not much of a revelation. But more specifically, every section you'll ever write will have either an even number of lines, or an odd number of lines. Wow. Even more of a revelation.

Let's talk a bit about lyrics with an odd number of lines. An odd number of lines feels odd — off balance, unresolved, incomplete, unstable. Let's say you're writing a verse where the idea is something like: “Baby, since you left me I've been feeling lost, odd, off balance, unresolved, incomplete, unstable.” Just theoretically, do you think this verse would be better with an even number of lines or an odd number of lines? Right. An odd number of lines.

This changes everything. You've recognized, maybe for the first time, that there can be a relationship between what you say and how many lines you use to say it. You're feeling unstable, and the odd, or unstable, number of lines supports that feeling. Prosody. Your structure (in this case, your number of lines) can support meaning.

An even number of lines tends to feel, well, even — solid, resolved, balanced, stable. Let's say that your message is something like: “Baby, you're the answer to all my prayers. I'll be with you forever. I'm your rock. You can count on me.” How many lines should you use? Odd or even? Right. Even. You want a solid feeling in the structure to support the emotion you're trying to communicate. “I mean it. You can trust me.” Prosody.

Now, for a really interesting case. What if you say, “Baby, you're the answer to all my prayers. I'll be with you forever. I'm your rock.

You can count on me,” and you say it in an odd number of lines? Do you trust this guy? I don't think so. Something doesn't feel right — there's a mismatch between what is being said and how it's put together, how it moves. Though the message promises stability, the motion creates instability, which pulls the rug out from under the narrator. It creates irony.

Let's look at the first verse again:

Her hat is hanging by the door

The one she bought in Mexico

It blocked the wind and stopped the rain

She'd never leave that one

So she can't be really gone

This feels unstable, though the message is: “Look at the evidence — it proves that she'll be coming back.” But the feeling we get from the unstable structure (which is acting like a film score) is that he's wrong and perhaps a bit hysterical or, at least, in denial.

So the number of lines can make a big difference.

What if the verse had been:

Her hat is hanging by the door

From Mexico, that funny store

I know she'd take her hat along

So I know she can't be really gone

Since the section feels balanced, we'd probably be convinced — there's a sense of resolution, balance, and completeness that we feel here. Go ahead, have some breakfast. Take the dog for a walk. She'll be home when you get back.

So an even number of lines supports stability and resolution, while an odd number of lines support the opposite.

2. Length of Lines

Line length is the traffic cop in your lyric. Two lines of equal length, because they're balanced, tell you to stop. (Note, for future reference, that the length of a line is not determined by the number of syllables, but by the number of stressed syllables, because the number of stressed syllables helps determine the number of musical bars.)

Her hat is hanging by the door

The one she bought in Mexico

The two four-stress lines feel balanced. It feels like we're finished with one thing and ready to start something new. Of course, we would feel even more stability if the lines rhymed, too. More on this later.

Lines of unequal length, because they do not reach a point of balance, tell you to keep moving:

It blocked the wind and stopped the rain

She'd never leave that one

Now we feel unbalanced and unresolved, and the traffic cop tells us to keep moving forward. Simple, but very effective.

The first three lines are equal length:

|

Stresses |

|

|

Her hat is hanging by the door |

4 |

|

The one she bought in Mexico |

4 |

|

It blocked the wind and stopped the rain |

4 |

But then something happens:

|

Stresses |

|

|

She'd never leave that one |

3 |

The three-stress line leaves us short, creating an unstable feeling — making us feel uncomfortable, like something's not quite right. The following line:

|

So she can't be really gone |

3 |

leaves us still feeling uncomfortable. With yet a second three-stress line, a new expectation kicks in: We'd like one more three-stress line.

Maybe something like:

|

She'll soon be coming home |

3 |

Which gives us:

|

Stresses |

|

|

Her hat is hanging by the door |

4 |

|

The one she bought in Mexico |

4 |

|

It blocked the wind and stopped the rain |

4 |

|

She'd never leave that one |

3 |

|

So she can't be really gone |

3 |

|

She'll soon be coming home |

3 |

Read it through a few times. See how comfortable it feels?

And now see how uncomfortable this feels:

|

Stresses |

|

|

Her hat is hanging by the door |

4 |

|

The one she bought in Mexico |

4 |

|

It blocked the wind and stopped the rain |

4 |

|

She'd never leave that one |

3 |

|

So she can't be really gone |

3 |

So there's a conspiracy between the number of lines and the line lengths to torpedo this guy — to expose him for the man in denial that he is. It's important to note that he isn't similarly exposed in the previous six-line structure.

There'll be a much more detailed treatment on the motion created by number of lines and line lengths in the next chapter, “Understanding Motion.”

3. Rhythm of Lines

First, let's acknowledge the difference between the rhythm of words and musical rhythm. Though they should match each other on the most important levels, they can also vary in many ways. For example, when we read, we normally don't extend a syllable for four beats, nor do we speed up parts of a line and slow other parts down significantly. Music does it all the time. What should remain constant between the rhythms of words and musical rhythm is this: Stressed syllables belong with stressed notes. Unstressed syllables belong with unstressed notes. This is called “preserving the natural shape of the language.” For our purposes here, we'll concentrate on lyric rhythm and leave musical rhythm for another time.

Let's look at the rhythm of our lyric. We've already marked the stressed syllables:

|

Her hat is hanging by the door |

4 |

|

The one she bought in Mexico |

4 |

|

It blocked the wind and stopped the rain |

4 |

|

She'd never leave that one |

3 |

|

So she can't be really gone |

3 |

This moves along in groups of two (da DUM):

Da DUM da DUM da DUM da DUM

Da DUM da DUM da DUM da DUM

Da DUM da DUM da DUM da DUM

Da DUM da DUM DUM da

Da da DUM da DUM da DUM

This is a mostly very regular lyric rhythm, with just a two variations, neither of which have much effect.

Okay, why, in a verse that feels so off balance (to support the off-balance emotion of the idea), is the rhythm so darn regular? Shouldn't it be off kilter, too?

Remember, this is a man in denial. He's trying to convince himself she's coming back. If everything in the verse were off kilter, there'd be nothing stable to rub against the unstable elements. Also, the differences in line length would become less clear and, therefore, less effective.

So the regularity of the rhythm, in this case, actually highlights the elements that throw it off balance.

4. Rhyme Scheme

Songs are made for listening — we hear them rather than see them.

Rhyme is a sonic event, made for listening. It provides our ear with road signs to guide us through the journey of the song. It shows us connections. It tells us when to stop and when to move forward. Look:

Her hat is hanging by the door

Her scarf is lying on the floor

This sounds finished. It stops us. It feels resolved, stable. But look at this:

Her hat is hanging by the door

She'd never leave that one

Her scarf is lying on the floor

Now we feel the push forward. Although, in this case, the line lengths also conspire to throw us off balance, leaning ahead, the rhymes can do it all by themselves:

door

one

floor

So rhyme guides our ear. Can a lack of rhyme maroon our ear without a guide? As in:

Her hat is hanging by the door

The one she bought in Mexico

It blocked the wind and stopped the rain

She'd never leave that one

So she can't be really gone

Our ear feels a little lost. And how is our hero feeling? Yup. Lost.

Is this to say that the lack of rhyme supports the emotion of the verse? Yup. It's huge. And, with a little practice, you can do it, too. These are tools, ready for use in any situation. Just apply the right tool in the right place and watch your song take on more color and more meaning.

Listen to “The Great Balancing Act” and see how Janis Ian and Kye Fleming create prosody with their abbb rhyme scheme.

Prosody comes from many directions, and rhyme scheme can be a big player. There's much more of this to come in chapter nineteen, “Understanding Motion.”

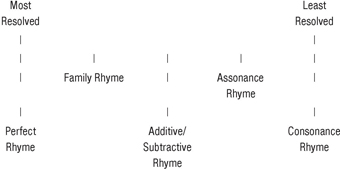

5. Rhyme Types Remember this?

RHYME TYPES:

SCALE OF RESOLUTION STRENGTHS

Remember, rhyme types create opportunities to add color and emotion. Use them to color your meaning, the same way a film score comments on the action on the screen.

There are no rules, only tools.

She'd never leave that one

So she can't be really gone

Here, the consonance rhyme, one/gone, conspires, along with the other elements of structure (number of lines, line length etc.), to help pull the rug out from under our hero, as well as to increase our feeling that something's not quite right. Good stuff.

So, did Gary Burr think about all this stuff as he wrote “Can't Be Really Gone”? Maybe, maybe not. The important issue is: You can.

The point of lyric analysis isn't to discover what a given writer intended to do. That's a fool's errand. Rather, lyric analysis digs into effective songs to discover what makes them work, to unearth tools for our own use.

Take the songs that move you and go beyond what they say and see how they're put together. You'll see how the film score of structure creates an extra dimension, adding emotion at every turn. Then use these structural tools to make your own songs dance.

Let's finish by looking at the five elements at work in Don Henley and Bruce Hornsby's “The End of the Innocence”:

Remember when the days were long

And rolled beneath the deep blue sky

Didn't have a care in the world

With mommy and daddy standin'by

Stable or unstable? Right. Stable. And how stable was my childhood? Well, my childhood had an even number of equal-length lines that rhymed perfectly at the second and fourth lines.

But happily ever after fails

And we've been poisoned by these fairy tales

The lawyers dwell on small details

Since daddy had to fly

Stable or unstable? Right. Stable. And where is it the most unstable? Right. The last line, where daddy leaves. How did daddy's leaving affect me? Well, it made me feel like my life sped up with consecutive rhymes, then dropped me over the edge with a short, unrhymed line. Darn it, daddy!

But I know a place where we can go

That's still untouched by men

We'll sit and watch the clouds roll by

And the tall grass wave in the wind

Stable or unstable? Hmm. Both? Yes. An even number of lines with matched alternating line lengths, rhyming lines two and four. That's what I'm promising you — a place where everything will feel stable again. But alas, though it might still feel better, there's not much you can do about the damage daddy's leaving did. No matter how stable the place we go feels, there's that darn men/wind consonance/additive rhyme, making everything hang. Real stability is now just an illusion. No perfect rhymes in sight.

You can lay your head back on the ground

And let your hair fall all around me

Offer up your best defense

But this is the end

This is the end of the innocence

Stable or unstable? Yep — very unstable. We'll never get our innocence back. Our life is always destined to be an odd number of unequal-length lines topped of by another consonance rhyme, defense/innocence.

A remarkable journey, where the structure supports — indeed, helps create — the emotional intent of the song.

Structure is your film score. Learn how to use it. Learn the effects that various structures can create, and use them to support your own ideas. Sometimes, you can even use them to create emotions underneath what you're saying.

In the next chapter, we'll take a systematic look at the effects of various structures. Fasten your seatbelts.