CHAPTER NINETEEN

UNDERSTANDING MOTION

One of the best ways to give your lyric extra punch is to understand how to make your lyric move, and how to make that motion support what you're saying — how to create prosody.

Sometimes, you may accidentally trip onto this sort of writing, unaware of the choices you're making. But if you tune into your lyrics' motion consistently, you'll not only write and rewrite your songs more effectively, but, more important, you won't rely on lucky accidents or divine inspiration to drop those good bits into your lap.

Lots of great ideas float by every day if we're awake and pay attention to what's inside us and around us. But it's how we deal with those magical ideas that create a better song.

In this chapter, we'll look at how lyric structure creates motion, which, in turn, creates emotion to be harnessed in support of what you want to say. You'll find plenty of exercises ahead to shape your motion muscles. If you do them all, you'll finish this chapter with tools and abilities you probably don't see now. I promise.

MOTION CREATES EMOTION

We feel something when a song speeds up, slows down, wants to move forward to the next place, wants to come to a resolution, and then arrives at home.

All by itself, the motion we create can take listeners on an interesting journey — a journey of feelings and attitudes. Lyric structure, all by itself, can:

-

move us forward to create excitement, anticipation, or an expectation of what's coming next.

-

slow us down to create a sense of holding back or a sense of unresolved feelings.

-

draw attention to a specific word (a spotlight), creating surprise, delight, humor, or any important emotion.

-

resolve, creating a feeling of stability.

-

leave us hanging and unresolved, creating a feeling of instability.

Again, motion creates emotion.

The primary emotion-producer in a lyric is the idea — the intent of the lyric, expressed in words and phrases. Since words “mean something,” they create emotion. If we also understand certain structural principles, we can amplify and support our ideas with dramatic results.

When we look at lines like this:

Turn down the lights, turn down the bed

Turn down these voices inside my head

— Mike Reid/Alan Shamblin

It makes us feel something. And I'm suggesting it's worth investigating what it makes us feel and why.

In lyrics, there are two elements that create motion and emotion:

1) the words and ideas themselves, and

2) the overall lyric structure, which consists of:

a. groupings of lines, and

b. line structure, a combination of three things:

-

rhythm of the line

-

length of the line (line length is determined by the number of stresses in a line), and

-

rhyme scheme used in the combinations of lines.

When you control the way a lyric moves, you're able to affect your audience on two levels simultaneously, rather than just on the level of meaning.

Motion creates emotion. Or, maybe better: Motion creates and supports emotion.

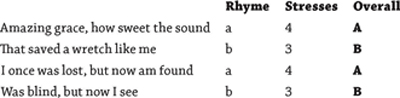

Let's first look at how the motion of a lyric, using four of the five basic structural elements (we'll leave out rhyme types) — an even number of lines, matched line length, stable rhythm, and stable rhyme scheme — can create a stable feeling:

|

Rhyme |

Stresses |

|

|

Amazing grace, how sweet the sound |

a |

4 |

|

That saved a wretch like me |

b |

3 |

|

I once was lost, but now am found |

a |

4 |

|

Was blind, but now I see |

b |

3 |

It's a stable common meter; the first and third lines both have the same line length, as do the second and fourth lines.

The rhyme scheme is abab, the same configuration as the line lengths (a four-stress line followed by a three-stress line, then another four-stress line followed by a three-stress line). The rhythms move along in a regular duple pattern (da DUM).

To notate the way a structure moves, let's use capital letters (e.g., A, B, C) to stand for lines that have both the same line lengths and the same rhyme scheme. Each line labeled with the same letter will:(1) rhyme with, (2) have the same number of stressed syllables as, and (3) have the same basic rhythm as every other line in the section with the same letter, as shown here in the far right column:

When these features (line length, rhyme, and number of stressed syllables) line up, the section's motion becomes clearer. This will also help you understand and control the way musical phrases work with lyrical phrases and help to you organize them in stable or unstable ways.

Once you get a feel for it, you'll be able to control motion in the real world of lyric writing, where mismatches can create productive tensions, as when rhyme scheme differs from the arrangement of line lengths. (For example, you can create tension when you have four equal-length lines that rhyme abab instead of aaaa. We'll see more of that later, but for now, let's keep it simple.)

In cases where the arrangement of line lengths doesn't match the rhyme scheme, we'll simply omit the capital As and Bs.

So, the five elements of structure, our friends from chapter eighteen, make your lyric structures move:

-

the rhythms of the lines

-

the arrangement of line lengths

-

the rhyme structure

-

the number of lines

-

the rhyme types

Let's review each of these elements to see how and when they affect motion.

The Rhythms of the Lines

The rhythm of a line is the first structural thing you hear in a song.

After hearing only the first line of a song, you don't yet know much about the motion of the whole section, but you might start to have a sense of what the intended emotion could be.

Rhythm is a prime mover in songwriting, and it can get complicated really fast. It has so many facets. In terms of its effect on our lyric sections, we can at least say this:

-

Regular rhythms create stable motion.

-

Irregular rhythms create less stable motion.

-

Two lines with matched rhythms create stability.

-

Two lines with unmatched rhythms create instability.

Since lyric rhythms work so intimately with musical rhythms, we'll have to leave the majority of this subject to another time. Look at chapter three of my book Songwriting: Essential Guide to Lyric Form and Structure, and also my online course “Writing Lyrics to Music,” available through patpattison.com.

For now, we'll stay with fairly regular rhythms and concentrate our efforts on the effects of line lengths, rhyme scheme, and number of lines on the movement of a section.

Structurally, the first line, by itself, communicates motion with its rhythm, and also with its length. It sets a standard, preparing us for what's to come in the remaining lines in the section. For example:

|

Rhyme |

Stresses |

|

|

I hitched to Tulsa worn and soaked |

a |

4 |

It's a steady duple rhythm (moving in twos — da DUM), and is four stresses long.

The Arrangement of Line Lengths

By the end of the first line, you know another basic structural piece of information: line length.

Starting at the second line, you will create structural motion, either by:

A) matching the first line, which will stop the motion, as seen here:

|

Rhyme |

Stresses |

|

|

I hitched to Tulsa worn and soaked |

a |

4 = A |

|

A little bent, a lotta broke |

a |

4 = A |

B) or not matching the first line, which pushes the motion forward, as seen here:

|

I hitched to Tulsa worn and soaked |

a |

4 = A |

|

I couldn't find a ride |

b |

3 = B |

Because these lines aren't matched, the structure keeps the motion moving forward, rather than slowing down or stopping it.

So, line lengths can create motion by the end of line two.

The Rhyme Structure

The earliest I can hear rhyme structure, and the motion caused by it, is at the end of the second line:

Example 1: aa rhyme structure with lines of matching length

|

I hitched to Tulsa worn and soaked |

a |

4 =A |

|

A little bent, a lotta broke |

a |

4 =A |

But often, we don't hear a section's rhyme structure until after line three:

Example 2: aba rhyme structure with the second line having a different length

|

I hitched to Tulsa worn and soaked |

a |

4 =A |

|

I stopped to get a bite |

b |

3 |

|

The waitress stared before she spoke |

a |

4 =A |

And sometimes it takes until the section is over before we are able to identify the rhyme structure:

Example 3: xaxa rhyme scheme

|

I hitched to Tulsa tired and worn |

x |

4 |

|

I stopped to get bite |

a |

3 =A |

|

A little bent, a lotta broke |

x |

4 |

|

A single quarter light |

a |

3 =A |

Note the way the line structure and the rhyme structure line up in this example as compared to the previous examples.

Line length and rhyme scheme are two independent tools. When they match, they form a couplet and the motion stops (example 1). But often, rhyme structure is created later than the motion created by line lengths (examples 2 and 3).

The Number of Lines — To Balance or Not

Obviously, you don't hear the total number of lines in a section until the end of the section, so it's one of the last two determiners of motion. Strong expectations have already been created by rhythm, rhyme scheme, and line length, but we still don't know for certain how the section will end.

In a stable section, the final line delivers resolution. An even number of lines gives it a solid footing. The expectations set up by the section are fulfilled, as in “Amazing Grace.” We feel like it's said its piece and really means it.

In an unstable section (like in “Can't Be Really Gone”), the final line could create a surprise or feeling of discomfort because the expectations are not completely fulfilled. An odd number of lines can certainly create a sense of discomfort. The final line could also lean forward toward the next section, in many cases moving into a contrasting section (e.g., a verse moving into a chorus).

The Rhyme Types

As we saw in the previous chapter, the kind of rhyme you choose can affect the stability of a section. More remote rhyme types will destabilize even the more stable constructions, as in lines 9–12 of “The End of the Innocence”.

As you go through the exercises in this chapter, try using stronger and weaker rhyme types in some of the closing positions to see what differences they make. We won't put rhyme types into the mix here, since there is more than enough work to do with just line lengths, rhyme scheme, and number of lines. No need to multiply examples with different rhyme types. But you already know what a huge tool rhyme types can be, so please stop every now and then to try out other possible types in the same structure.

With the tools you're about to acquire, you'll be able to control how stable or unstable your section will be — anything from a granite boulder to a wobbly table to a capsizing ship.

STABILITY VS. INSTABILITY

Okay, it's time to get practical. You'll be looking at wheelbarrows full of different kinds of sections, organized according to their numbers of lines, and listed from the most stable sections to the least stable sections.

Think of the following examples as a handy reference guide to stable and unstable structures, there for you to try in support of that idea you've got. Is the idea stable or unstable? And then you go through the examples to find something that might work for you.

We'll start by looking at two-line sections, then spend a bit of time on three-line sections. Though three-line sections are more rare as standalone sections in lyric writing, looking at them will give you a good view of what causes a section to move. Then we'll go on to four-line and five-line sections, and, finally, a few interesting six-line sections. Since larger sections are usually made up of smaller pieces, understanding how these smaller sizes move will get you ready for pretty much anything else. If you stay with it and dig into each example to see how it feels, you'll add a whole new dimension to your lyric writing.

Combinations Of Two Lines

Here are all the possible two-line sections, listed from most to least stable. Stable asks you to stop:

|

I hitched to Tulsa worn and soaked |

a |

4 =A |

|

A little bent and really broke |

a |

4 =A |

It stops. You can feel the resolution.

|

I hitched to Tulsa worn and soaked |

a |

4 |

|

A little bent and really tired |

b |

4 |

Even though the lines don't rhyme, their matched lengths give a feeling of balance or stability. Not as much as if they rhymed, but enough to keep you from wanting to lunge forward. It feels a little more stable than this:

|

I hitched to Tulsa worn and soaked |

a |

4 |

|

A little bent and broke |

a |

3 |

Even though these rhyme, they rhyme in different positions — most likely on different beats in the musical measure. There's a little stronger push forward here. So line length is a stronger motion creator than rhyme, huh? Yup. Unstable lines ask you to keep moving:

|

I hitched to Tulsa worn and soaked |

a |

4 |

|

I couldn't find a ride |

b |

3 |

This is the least stable. It leans forward really hard.

Here's an interesting lesson in motion: a longer line, followed by a shorter line, like this:

|

I hitched to Tulsa worn and soaked |

a |

4 |

|

I couldn't find a ride |

b |

3 |

leans ahead harder than the opposite:

|

I couldn't find a ride |

a |

3 |

|

I hitched to Tulsa worn and soaked |

b |

4 |

The longer line has matched the shorter line on its way by. Which is not the case here:

|

I hitched to Tulsa worn and soaked |

a |

4 |

|

I couldn't find a ride |

b |

3 |

You can feel the difference. Remember this, since it will also apply to larger structures: Longer followed by shorter is less stable than shorter followed by longer.

In working through these examples and the ones to follow, we'll stick to the staple four-stress, three-stress, and, later, five-stress lines that make up most lyrics. But once you absorb the principles, you'll be able to apply them to any line lengths.

Combinations Of Three Lines

The possibilities of three lines, listed from most stable to least stable, are:

AAA

|

She stared at me before she spoke |

a |

4 =A |

|

She said the day had come to go |

a |

4 =A |

|

A little bent, a lotta broke |

a |

4 =A |

|

I hitched to Tulsa worn and soaked |

a |

4 =A |

This is the most stable of the three-line sequences. It seems almost to close down — almost to resolve. You can look at it as AA+A, and it depends on whether you see the third line leaning back or looking forward for more. The principle of sequence says it's looking to pair off, since we heard a pairing (a resolving couplet) after line two. Even if we feel the third A leaning back, the structure still feels a bit off balance. Either way, it feels less than complete.

If you think otherwise, remember that sometimes what you're saying can influence your structural ear. In the sequence above, line three is about what he did because of what she said. The idea feels completed. But he still doesn't feel happy about it. But look at this:

|

I hitched to Tulsa worn and soaked |

a |

4 =A |

|

She stared at me before she spoke |

a |

4 =A |

|

She said the day had come to go |

a |

4 =A |

This feels a little less resolved, since the idea is less resolved. This is where it gets fun. Watching structure influence content, and content influence structure. Composition, in regard to songwriting, is the activity of mixing and matching these elements.

John Mayer uses the AAA effectively by simply repeating the title of his song “Your Body Is a Wonderland”:

Your body is a wonderland

Your body is a wonderland

Your body is a wonderland

After the first and second verse, it feels like he wants more, leaning ahead. Only after the bridge does he finally say it four times, bringing the events to their conclusion.

EXERCISE 26

Write an AAA structure, first using ideas that come to a conclusion, and then using ideas that feel less resolved. How much difference do you feel in the stability of the section?

ABB

|

It rained like hell the day I left my place |

a |

5 =A |

|

She said the day had come to go |

b |

4 =B |

|

I hitched to Tulsa worn and soaked |

b |

4 =B |

The longer first line actually seems to create a bit of expectation for a matching A at line four. Though this is still unstable, it is relatively stable for a three-line sequence. Perhaps there's a difference if we begin with a shorter line:

|

It rained the day I left |

a |

3 =A |

|

She said the day had come to go |

b |

4 =B |

|

I hitched to Tulsa worn and soaked |

b |

4 =B |

Now, it doesn't seem to lean as hard as it did with the longer first line. With the shorter first line, it feels more stable — almost like its own section. The singer feels almost resigned to leaving, like he's accepted his fate. Interesting.

EXERCISE 27

Write an ABB structure, first with a longer first line, then with a shorter one. Keep them as much the same as possible. Do you feel a difference in attitude between them? Structure can support or even sometimes determine the attitude of the character.

XXX

|

I hitched to Tulsa worn and soaked |

x |

4 |

|

The waitress stared and smiled at me |

x |

4 |

|

I stopped to rest a little while |

x |

4 |

This more “floats” than leans forward. There is no rhyme sequence established here, so few expectations are raised. It sort of “suspends” him — he feels like he's just hanging out, waiting to see what happens next, but with no hurry.

AAB

|

I hitched to Tulsa worn and soaked |

a |

4 =A |

|

She stared at me before she spoke |

a |

4 =A |

|

I stopped a little while |

b |

3 =B |

This leans pretty hard, too, though not in the same way, since our expectations are a little less clear; maybe the resolution would be AABB, or maybe AAB AAB. If we complete it either way, it becomes a stable section. But if we use it as a three-line section, it would be pretty unstable.

If it were a pre-chorus or bridge, we could maybe use the third line's vowel sound from while (which is asking to be rhymed) to illuminate an important vowel sound in the oncoming section — for example, in an oncoming chorus where the title of the song was something like “For One Smile in a Million.” The while in line three, hanging there unrhymed, will emphasize smile in the chorus. Nifty tool, eh?

EXERCISE 28

Make up your own title, and, using it as the first line of an oncoming chorus, write an AAB structure leading up to it, with the third line targeting a vowel sound in the title. Try not to target the end rhyme. Instead, give the words inside the title a sonic boost. Then rewrite the third line (B line) to target a different vowel sound in the title. As in the sample that follows.

|

I hitched to Tulsa worn and soaked |

a |

4 =A |

|

She stared at me before she spoke |

a |

4 =A |

|

I stopped, completely dumb |

x |

3 =B |

Now the third line targets the short-u sound in the title's one, high-lighting it and emphasizing it in the chorus.

There's also:

|

I hitched to Tulsa worn and soaked |

a |

4 =A |

|

She stared at me before she spoke |

a |

4 =A |

|

I stopped, completely still |

x |

3 =B |

For one smile in a million …

Now the third line targets the short-i and l sounds in million, highlighting it and emphasizing it in the chorus.

Now we've targeted the rhyme position. Note that the effect not only highlights it, but it also creates a bit of a sense of resolution. It feels like:

|

I hitched to Tulsa worn and soaked |

x |

4 =X |

|

She stared at me |

x |

2 =X |

|

I stopped, completely still |

a |

3 =A |

|

For one smile in a million |

a |

3 =A |

Targeting the rhyme position is neither wrong nor right. It creates a different, usually more resolved feeling than if you target interior vowel sounds. It depends on the feeling you want to create. You control it.

ABA

|

I hitched to Tulsa worn and soaked |

a |

4 =A |

|

I stopped a little while |

b |

3 =B |

|

She stared at me before she spoke |

a |

4 =A |

This is not only the most unstable of the three-line sequences, it also positively cries out for a resolving fourth line with three stresses and a rhyme with while. This three-line structure establishes a clear pattern, so we know what's coming next.

With this structure, we're looking at three-fourths of a common meter section, so the conclusion is more than obvious. It's interesting to see how the same principle would work with a different arrangement. Instead of longer / shorter / longer, let's try shorter / longer / shorter:

|

I hitched the Tulsa road |

a |

3 =A |

|

I stopped a while to grab a bite |

b |

4 =B |

|

She stared before she spoke |

a |

3 =A |

You can still feel the strong lean forward, now expecting a four-stress line rhyming with bite. It seems to lean even harder with a five-stress line in the second position:

|

I hitched the Tulsa road |

a |

3 =A |

|

I stopped a little while to grab a bite |

b |

5 =B |

|

She stared before she spoke |

a |

3 =A |

I'm not sure why this raises more expectations than the four-stress line. Perhaps it's because it feels like more of a departure from line one.

Of course, if you complete the sequence, you have a stable four-line structure. If you leave it as a three-line sequence, then you'll be moving pretty strongly into the next section. Perhaps this might make an interesting pre-chorus structure. Again, you could use a sound at the end of line two to target an important sound in the chorus. For example:

Pre-chorus

I hitched the Tulsa road

I stopped a little while to grab a bite

She stared, and then she spoke

Chorus

Baby I like what I see …

We hear like with more intensity: “Baby I like what I see.” We could try targeting baby:

Pre-chorus

I hit the Tulsa road

I stopped a little while to grab some shade

She stared, and then she spoke

Chorus

Baby I like what I see …

We hear baby with sensual overtones. Compare this to if we don't target:

Pre-chorus

I hitched the Tulsa road

I stopped a little while to grab a drink

She stared, and then she spoke

Chorus

Baby I like what I see …

Now we get no extra sonic action in the chorus, and line two's drink is still waving his arms for attention, wondering if he'll ever meet a nice noun or verb to hook up with.

EXERCISE 29

Make up your own title, and, using it as the first line of an oncoming chorus, write an ABA structure leading up to it. Make the second line's ending vowel target a vowel sound inside your title. Then rewrite the second line's ending again to target a different vowel sound in your title.

COMBINATIONS OF FOUR LINES

Understanding basic three-line motion helps you understand how to move a section forward and how to stop it. It gives you the ability to control motion, and therefore use the way a structure moves and feels to support your ideas — for example, making the structure move haltingly when the protagonist is unsure of what to do next. Your study of three-line sequences not only helps you understand how and why lines float or raise expectations by pushing forward, it also shows you how to resolve the section, often with just one more line.

We'll now look at four-line sections from most stable to least stable; some of them pretty stable, some that fool you a little, some with little surprises, and some that are still unstable and moving forward.

AAAA

|

She stared at me before she spoke |

a |

4 =A |

|

She said the day had come to go |

a |

4 =A |

|

A little bent, a lotta broke |

a |

4 =A |

|

I hitched to Tulsa worn and soaked |

a |

4 =A |

Lots of stability here — it's basically Eenie Meenie Miney Moe. It has two balancing points: at the end of line two and at the end of line four. This is as solid as a structure can get. Relatively speaking, it doesn't move much, since it stops you in the middle, breaking into two matched two-line sections. The third A connects a bit with the first two, so, as we saw in the three-line AAA section, the lean forward toward the last line is pretty weak. So the last line isn't quite as much a “point of arrival” as it will be in other structures. The spotlights aren't as bright. If this were a chorus, it would be a good opportunity to put the title in both the first and last line:

|

A little bent, a lotta broke |

a |

4 =A |

|

She said the day had come to go |

a |

4 =A |

|

I hitched to Tulsa worn and soaked |

a |

4 =A |

|

A little bent, a lotta broke |

a |

4 =A |

It's a nice surprise to hear it repeated, but we weren't being pulled inexorably toward it. The journey was much more steady, almost matter-of-fact. The structure portrays an attitude.

EXERCISE 30

Match the AAAA structure above using your own words and your own title at the top and bottom.

AABB

|

I hitched to Tulsa worn and soaked |

a |

4 =A |

|

A little bent, a lotta broke |

a |

4 =A |

|

I stopped a bit to get a bite |

b |

5 =B |

|

Found myself a quarter light |

b |

5 =B |

With AAB we get a stronger push forward than AAA gave. We've heard a different sound and now are looking to pair it with another B. We still get a complete stop at the end of line two, and then again creating two two-line sections. A very stable structure. When the protagonist says something using this structure, he/she's telling the truth. It's a stable fact.

ABAB

|

I hitched to Tulsa worn and soaked |

a |

4 =A |

|

I stopped to get a bite |

b |

3 =B |

|

A little bent, a lotta broke |

a |

4 =A |

|

A single quarter light |

b |

3 =B |

Boy, does this stop dead. Common meter, fully resolved but full of motion. We get a push forward by the shorter line two, then a big push when we hear line three match line one in length and rhyme. As before, ABA raises strong expectations for the repeat of B. This is called common meter for a reason. It's everywhere.

EXERCISE 31

Find five examples of common meter in songs you know. It shouldn't take long.

XAXA

|

I hitched to Tulsa tired and worn |

x |

4 =X |

|

I stopped to get bite |

a |

3 =A |

|

A little bent, a lotta broke |

x |

4 =X |

|

A single quarter light |

a |

3 =A |

Now we're missing the big rhyme push forward at line three; the line length pushes, but without the additional momentum rhyme creates. This moves forward pretty strongly, but without the urgency we feel at line three of ABAB.

EXERCISE 32

Modify your earlier ABAB structure to an XAXA structure. Feel the weaker push at line three?

ABAA

|

I hitched to Tulsa worn and soaked |

a |

4 =A |

|

I stopped to get a bite |

b |

3 =B |

|

A little bent, a lotta broke |

a |

4 =A |

|

I bummed a meal, bummed a smoke |

a |

4 =A |

We saw this structure in chapter fifteen, a deceptive resolution; it's a great way to call extra attention to the last line. Make sure there's something there worth looking at. ABAA is also a handy structure for putting a title on top and bottom:

|

A little bent, a lotta broke |

a |

4 =A |

|

I stopped to get a bite |

b |

3 =B |

|

I bummed a meal, bummed a smoke |

a |

4 =A |

|

A little bent, a lotta broke |

a |

4 =A |

The same targeting strategy we saw before works here, too: If a verse were ABAA, you could use a sound in the verse at the end of line two to target an important sound in the chorus. For example:

Verse

|

I hitched to Tulsa worn and soaked |

a |

4 =A |

|

I stopped to get a bite |

b |

3 =B |

|

A little bent, a lotta broke |

a |

4 =A |

|

She smiled at me before she spoke |

a |

4 =A |

Chorus

Baby I like what I see …

As before, we hear like with more intensity: “Baby I like what I see.” Again, we could try targeting baby:

Verse

|

I hitched to Tulsa worn and soaked |

a |

4 =A |

|

I had to get away |

b |

3 =B |

|

A little bent, a lotta broke |

a |

4 =A |

|

She smile at be before she spoke |

a |

4 =A |

Chorus

Baby I like what I see …

Now we hear baby with the same sensual overtones. Compare this to if we don't target a vowel sound in the chorus:

Verse

|

I hitched to Tulsa worn and soaked |

a |

4 =A |

|

Stopped to get some grub |

b |

3 =B |

|

A little bent, a lotta broke |

a |

4 =A |

|

She smile at be before she spoke |

a |

4 =A |

Chorus

Baby I like what I see …

A wasted second position? Maybe not. But it's there for the picking if you want it.

EXERCISE 33

Make up your own title, and, using it as the first line of an oncoming chorus, write an ABAA structure leading up to it, with the second line targeting a vowel sound in the title. Try not to target the end rhyme. Instead, give the words inside the title a sonic boost. Then rewrite the end sound in your second line to target a different vowel sound in the title.

XXAA

|

I hitched my way to Tulsa |

x |

3 =X |

|

Stopped to get a bite |

x |

3 =X |

|

I bummed a meal, bummed a smoke |

a |

4 =A |

|

A little bent, a lotta broke |

a |

4 =A |

This is a surprise. We had no expectations after either line two or three, so the resolution we get at line four surprises (but doesn't fool) us. It's resolved all right, but without much pushing or raising expectations to get there. Resolution coming out of chaos, as it were, which can be a useful tool to support a similar motion of ideas. It's pretty unstable for a resolved section.

Vary the rhyme, but not the line lengths, and you'd get something like:

|

I hitched to Tulsa worn and frayed |

x |

4 =X |

|

Stopped a while to get a bite |

x |

4 =X |

|

I bummed a meal, bummed a smoke |

a |

4 =A |

|

A little bent, a lotta broke |

a |

4 =A |

The lights still go on the last line, but not as brightly, given the more balanced journey through line lengths.

XAAA

|

I hitched to Tulsa worn and soaked |

x |

4 =X |

|

I stopped to get a bite |

a |

3 =A |

|

A single quarter light |

a |

3 =A |

|

And such an appetite |

a |

3 =A |

Still stable, but getting less so. Again, changing both the rhyme and line length gives us a clearer view of the motion.

With the shorter A lines above, the sequence leans a bit forward, almost as if it were asking to duplicate itself for balance. It still feels closed, but a bit unstable, certainly less stable than this:

|

She stared at me a while |

x |

3 =X |

|

She said the day had come to go |

a |

4 =A |

|

I hitched to Tulsa worn and soaked |

a |

4 =A |

|

A little bent, a lotta broke |

a |

4 =A |

As usual, longer lines following shorter lines create more stability. Think of longer lines as laying a foundation under the shorter line above them. This version of XAAA is pretty stable, as it would be if all the line lengths matched, like this:

|

She stared at me a little while |

x |

4 =X |

|

She said the day had come to go |

a |

4 =A |

|

I hitched to Tulsa worn and soaked |

a |

4 =A |

|

A little bent, a lotta broke |

a |

4 =A |

What creates the instability in all three versions is the odd number of A's. There's a mismatch between the number of lines, and the number of matched elements. The structure doesn't push forward very hard, it more “floats,” because when we get our first match at line three, we have an odd number of lines preventing the rhyme and rhythm match from creating stability. We don't quite know what to expect next, making the final A create what feels like a stopping place, but without much fanfare when it arrives.

AABA

|

I hitched to Tulsa worn and soaked |

a |

4 =A |

|

A little bent, a lotta broke |

a |

4 =A |

|

I stopped to get a bite |

b |

3 =B |

|

I bummed a meal, bummed a smoke |

a |

4 =A |

This structure fools us, too, but not drastically. To the extent that we expect a match for B, we're fooled when it resolves with A.

This structure doesn't move much. It balances after line two, so there's no push forward there. The B line provides the only push, but only by being different and asking politely to be matched. We get a little spotlight on the last line.

EXERCISE 34

Make up your own title, and, using it as the first line of an oncoming chorus, write an AABA structure leading up to it, with the third line targeting a vowel sound in your title. Then, find a different end vowel for your third line to target a different vowel sound in your title. Then see what happens when you target the end rhyme.

ABBA

|

I hitched to Tulsa getting worn and soaked |

a |

5 =A |

|

I stopped a bit to get a bite |

b |

4 =B |

|

Found myself a quarter light |

b |

4 =B |

|

A little bent, a lotta really broke |

a |

5 =A |

As you'd expect, the longer line at the end of the example above makes it feel pretty resolved. But it feels less resolved with the longer lines inside:

|

As thunder rolled across the sky |

a |

4 =A |

|

I hitched to Tulsa getting worn and soaked |

b |

5 =B |

|

A little bent, a lotta really broke |

b |

5 =B |

|

Found myself a quarter light |

a |

4 =A |

It certainly feels less stable with the shorter line on the outside. Look at it with equal-length lines:

|

As thunder rolled across the sky |

a |

4 =A |

|

I hitched to Tulsa worn and soaked |

b |

4 =B |

|

A little bent, a lotta broke |

b |

4 =B |

|

Found myself a quarter light |

a |

4 =A |

In poetry, this is called an In Memoriam Quatrain, after Alfred Lord Tennyson's lovely poem of the same title. He used an ABBA rhyme scheme and equal-length lines, creating a suspended feeling at the end of each quatrain, much as you'd do in a eulogy. The structure's feeling was so appropriate for the message of his poem (an actual eulogy), that the abba rhyme scheme has carried the poem's name ever since.

ABBA structures float. I think it's unresolved, but sometimes it's a close call. No matter, though; it's the effect of the structure that counts. It leans a bit, asking maybe for:

|

As thunder rolled across the sky |

a |

4 =A |

|

I hitched to Tulsa getting worn and soaked |

b |

5 =B |

|

A little bent, a lotta really broke |

b |

5 =B |

|

Found myself a quarter light |

a |

4 =A |

|

I knew I'd have to stay the night |

a |

4 =A |

Or maybe even:

|

As thunder rolled across the sky |

a |

4 =A |

|

I hitched to Tulsa getting worn and soaked |

b |

5 =B |

|

A little bent, a lotta really broke |

b |

5 =B |

|

Found myself a quarter light |

a |

4 =A |

|

The waitress said she'd maybe take me home |

b |

5 =B |

|

Then vanished in a lovely puff of smoke |

b |

5 =B |

ABBA is an interesting section. Check out the verses to James Taylor's “Sweet Baby James.”

AAAX

|

I hitched to Tulsa worn and soaked |

a |

4 =A |

|

A little bent, a lotta broke |

a |

4 =A |

|

I bummed a meal, bummed a smoke |

a |

4 =A |

|

Bummed another ride |

b |

3 =X |

This is an unstable section. As you've already seen, AAA doesn't push very hard, but it does lead us to expect another A, so when we don't get it, we still want it (the targeting principle). Most likely, we'll look for a whole section to match it:

|

I hitched to Tulsa worn and soaked |

a |

4 =A |

|

A little bent, a lotta broke |

a |

4 =A |

|

I bummed a meal, bummed a smoke |

a |

4 =A |

|

Bummed another ride |

b |

3 =B |

|

She'd closed her eyes before she spoke |

a |

4 =A |

|

Said the time had come to go |

a |

4 =A |

|

To vanish in a puff of smoke |

a |

4 =A |

|

A phantom in the night |

b |

3 =B |

See the verses in David Wilcox's “Eye of the Hurricane” on page 163 for an effective use of this eight-line sequence.

Another possibility for this structure is to use the X line as a title position, like this:

|

I hitched to Tulsa worn and soaked |

a |

4 =A |

|

A little bent, a lotta broke |

a |

4 =A |

|

I bummed a meal, bummed a smoke |

a |

4 =A |

|

Looking for something more |

x |

3 =X |

Okay, even though it's a dumb title, you see the point: The structure supports the content.

AXAX

|

I hitched to Tulsa worn and soaked |

a |

4 =A |

|

I stopped to get a bite |

x |

3 =X |

|

I bummed a meal, bummed a smoke |

a |

4 =A |

|

Found a room |

x |

2 =X |

This one pushes ahead pretty hard, asking for a match to line two. When the match isn't forthcoming, we fall forward. This might be a good technique for setting up a title:

|

I hitched to Tulsa worn and soaked |

a |

4 =A |

|

I stopped to get a bite |

b |

3 =X |

|

I bummed a meal, bummed a smoke |

a |

4 =A |

|

Found a room |

x |

2 =X |

|

Lighting the fire inside |

b |

3 =X |

Here's a more normal version, with lines two and four matching lengths:

|

I hitched to Tulsa worn and soaked |

a |

4 =A |

|

I stopped to get a bite |

b |

3 =X |

|

I bummed a meal, bummed a smoke |

a |

4 =A |

|

Found a quiet room |

x |

3 =X |

|

Lighting the fire inside |

b |

3 =X |

Each structure is what it is, but always keep an eye out for what else it could become — for what could come next.

Here's AXAX with a longer last line:

|

I hitched to Tulsa worn and soaked |

a |

4 =A |

|

I stopped to get a bite |

x |

3 =X |

|

I bummed a meal, bummed a smoke |

a |

4 =A |

|

Found a place to sleep before it rained |

x |

5 =X |

Again, the section with the longer last line feels a little more stable, since it has matched line two's length (our expectation) on its way to the end. Still, it's pretty unstable, but not as unstable as it was with the shorter line.

XAAX

|

I hitched a ride to Tulsa |

x |

3 =X |

|

I stopped a bit to get a bite |

a |

4 =A |

|

Found myself a quarter light |

a |

4 =A |

|

A little bent, a lotta really broke |

x |

5 =X |

As usual, the second A takes the wind out of the sails by throwing off any expectations of what might come next. It doesn't push forward too hard, and the section continues to float.

|

I hitched to Tulsa getting lost and worn |

a |

5 =X |

|

I stopped a bit to get a bite |

b |

4 =A |

|

Found myself a quarter light |

b |

4 =A |

|

A lotta really broke |

a |

3 =X |

This version looks forward, hoping for a stable place to land, wherever that might be.

EXERCISE 35

Using the previous example, see if you can find our friend a landing place.

XXXX

|

I hitched to Tulsa getting worn and frayed |

a |

5 =X |

|

I stopped to get a bite |

b |

3 =X |

|

Found myself a quarter short |

b |

4 =X |

|

A lotta broke |

a |

2 =X |

Or:

|

A lotta broke |

a |

2 =X |

|

I hitched to Tulsa getting worn and frayed |

a |

5 =X |

|

I stopped to get a bite |

b |

3 =X |

|

Found myself a quarter short |

b |

4 =X |

Or:

|

A lotta broke |

a |

2 =X |

|

I stopped to get a bite |

b |

3 =X |

|

Found myself a quarter short |

b |

4 =X |

|

I hitched to Tulsa getting worn and frayed |

a |

5 =X |

Or this, unrhymed, with equal-length lines:

|

I hitched to Tulsa worn and frayed |

x |

4 =X |

|

Stopped a while to get a bite |

x |

4 =X |

|

Found myself a quarter short |

x |

4 =X |

|

A lotta broke, a lotta bent |

x |

4 =X |

Food For Thought

How does each section feel? Though all of them are unstable, which one feels most unstable? Least unstable? Why?

We've now seen some of lyric writing's most stable sections, excellent for supporting stable ideas. Of course, having four lines doesn't mean you have to stop there. Unstable four-line sequences often add more lines to stabilize or resolve themselves. But stable four-line, and they often do, to wondrous effects.

COMBINATIONS OF FIVE LINES

Groups With Only One Matching Element

In this first group of five-line sequences, listed from most stable to least stable, any odd lines don't match anything else, including each other. This often creates a “floating” effect. The sections that feel most stable are often the ones that surprise us by feeling resolved without us expecting the resolution. Call it “unexpected closure.” These structures are probably most useful as verses, though they can also work effectively as choruses, given the proper combination of ideas.

AAAAA

|

It rained the day I left my home |

a |

4 =A |

|

I hitched to Tulsa worn and soaked |

a |

4 =A |

|

She stared at me before she spoke |

a |

4 =A |

|

I told her then that I was broke |

a |

4 =A |

|

I watched her turn around to go |

a |

4 =A |

The fifth line is an unexpected closure, and though it tips a tad toward a sixth line, it just as much leans back in warm companionship with all the other A's. Line five would be an excellent place to repeat a title that's been stated at line one:

|

A little bent, a lotta broke |

a |

4 =A |

|

I hitched to Tulsa worn and soaked |

a |

4 =A |

|

She stared at me before she spoke |

a |

4 =A |

|

I watched her turn around to go |

a |

4 =A |

|

A little bent, a lotta broke |

a |

4 =A |

XAAAA

|

It rained the day I left my home for good |

x |

5 =X |

|

I hitched to Tulsa worn and soaked |

a |

4 =A |

|

She stared at me before she spoke |

a |

4 =A |

|

I told her then that I was broke |

a |

4 =A |

|

I watched her turn around to go |

a |

4 =A |

Expectations play leapfrog here. After line three, we want to stop with the matching As, but we can't because of the odd number of lines. When the number of lines is even, the number of As is odd, and so on. It's resolved (unexpected closure) at line four, so the fifth line is an unexpected closure, too. You can feel its instability, like it might just want to move again to balance the number of lines. It's a nice place to spotlight an important idea.

EXERCISE 36

Write an XAAAA section that ends with a stable idea, then juggle the lines so it ends with an unstable idea. Can you feel how the content and structure interact?

XXAAA

|

It rained the day I left my home for good |

x |

5 =X |

|

I couldn't start my car |

x |

3 =X |

|

I hitched to Tulsa worn and soaked |

a |

4 =A |

|

She stared at me before she spoke |

a |

4 =A |

|

I told her then that I was broke |

a |

4 =A |

As we saw above with XXAA, we have unexpected closure at line four.

Line five creates another unexpected closure, but one that leans forward. We have a pretty strong push for a sixth line, since we could use both another line and another A to even things up.

Let's try it with longer As:

|

It rained the day I left my home |

a |

4 =X |

|

I had to get away |

b |

3 =X |

|

I had to find a place where I could breathe |

c |

5 =A |

|

A place that had some grass and apple trees |

c |

5 =A |

|

Where I could finally find a little peace |

c |

5 =A |

Pretty stable. Does the closure at line four fool you, or simply surprise you? The answer depends on whether you have any expectations after the first three lines.

It's clear that a place that had some grass and apple trees stabilizes the section after four lines. If you can predict what should come next, you have expectations. Frankly, I don't have any predictions after line three — it could go anywhere. Thus, the resolution we feel is something we didn't expect — unexpected closure. It's more of the same at line five, with two lines in the spotlights here.

XAXAA

|

It rained the day I left |

x |

3 =X |

|

I hitched to Tulsa worn and soaked |

a |

4 =A |

|

My thumb my only ticket |

x |

3 =X |

|

A little bent, a lotta broke |

a |

4 =A |

|

She stared at me before she spoke |

a |

4 =A |

EXERCISE 37

Your turn to describe how this one behaves.

XXXAA

|

It rained the day I left my home for good |

x |

5 =X |

|

I couldn't start my car |

x |

3 =X |

|

I thought I'd try some thumbing |

x |

3+ =X |

|

I hitched to Tulsa worn and soaked |

a |

4 =A |

|

A little bent, a lotta broke |

a |

4 =A |

This feels like it stops, too, though it's predictably off balance because of the odd number of lines. This one's a floater, though there may be a little voice asking for a 3+ line ending in numb me.

XXAXA

|

It rained the day I left my home for good |

x |

5 =X |

|

I couldn't start my car |

x |

3 =X |

|

I hitched to Tulsa worn and soaked |

a |

4 =A |

|

Stopping at the roadside |

x |

2+ =X |

|

She stared at me before she spoke |

a |

4 =A |

This one is clearly open after line four, without much of a push forward after line three, except by our preference for stable, even numbers. It resolves, unexpectedly, at line five, but floats everywhere else. Even after line five, it feels like it might want to move. Perhaps a 2+ line ending in low ride would settle things down? What sort of ideas would this XXAXA structure support?

AAAAX

|

It rained the day I left my home |

a |

4 =A |

|

I hitched to Tulsa worn and soaked |

a |

4 =A |

|

She stared at me before she spoke |

a |

4 =A |

|

I told her then that I was broke |

a |

4 =A |

|

I watched her turn her back |

x |

3 =X |

Five-line systems ending with an X will be the most unstable.

Groups With Two Matching Elements

In this first group with two matching elements (As and Bs), the first two lines are different, creating forward motion. They are listed from most stable to least stable.

ABABB

|

I hitched to Tulsa worn and soaked |

a |

4 =A |

|

I had to get away |

b |

3 =B |

|

She stared at me before she spoke |

a |

4 =A |

|

With not a word to say |

b |

3 =B |

|

Her smile began my day |

b |

3 =B |

Closed and stable, with the additional line leaning more backward than forward. You get a nice spotlight at the end.

ABAAB

|

I hitched to Tulsa worn and soaked |

a |

4 =A |

|

I had to get away |

b |

3 =B |

|

The waitress stared before she spoke |

a |

4 =A |

|

I told her then that I was broke |

a |

4 =A |

|

Her smile began my day |

b |

3 =B |

Interesting case here. Line four fools you — call it a “deceptive closure”: You expected B, but got A instead. Then, at line five, you get what you originally expected but where you didn't expect it, so it's a cross between expected and unexpected closure, making it feel a bit more stable.

ABBAA

|

I hitched to Tulsa worn and soaked |

a |

4 =A |

|

I had to get away |

b |

3 =B |

|

To find another place |

b |

3 =B |

|

I told the waitress I was broke |

a |

4 =A |

|

I watched her turn her back to go |

a |

4 =A |

This one is interesting. Look back at the ABB structure in “Combinations of Three Lines” on page 198 to see the effect created here. Check out the first three lines of the second verse of Gary Nicholson and John Jarvis's “Between Fathers and Sons”:

|

Now when I look at my own sons |

a |

3+ =A |

|

I know what my father went through |

b |

3 =B |

|

There's only so much you can do |

b |

3 =B |

How stable does this section feel? Do you have any expectations of where it might go? Probably not. Whatever you do, it will stay pretty unstable unless you match it with three more lines of ABB.

ABBAB

|

I hitched to Tulsa worn and soaked |

a |

4 =A |

|

I had to get away |

b |

3 =B |

|

To find another place |

b |

3 =B |

|

I told the waitress I was broke |

a |

4 =A |

|

Her smile began my day |

b |

3 =B |

It looks like we've started a second ABB sequence with the addition of AB, asking for the next B, something like:

|

She said she'd let me stay |

b |

3 =B |

But the push doesn't seem too strong, since the sequence, though visible, doesn't seem too audible. This five-line sequence feels a bit unstable, but only a bit.

ABAAA

|

I hitched to Tulsa worn and soaked |

a |

4 =A |

|

Stopped to grab a bite |

b |

3 =B |

|

The waitress stared before she spoke |

a |

4 =A |

|

I told her then that I was broke |

a |

4 =A |

|

And watched her turn her back to go |

a |

4 =A |

There's a deceptive closure in line four, thus creating an unexpected closure in line five. As we saw in chapter fifteen “Spotlighting With Common Meter,” the structure leans forward to match the B line with something like:

|

Have a lovely night |

b |

3 =B |

There are four As but five lines, leaning a little for a sixth line. It stops at line five, but it's not a hard stop. It's a bit of a floater without a sixth line.

ABABA

|

I hitched to Tulsa worn and soaked |

a |

4 =A |

|

I had to get away |

b |

3 =B |

|

She stared at me before she spoke |

a |

4 =A |

|

With not a word to say |

b |

3 =B |

|

I told her then that I was broke |

a |

4 =A |

This leans forward looking for another B. The alternating sequence is responsible for this feeling.

More Groups With Two Matching Elements

In this next group, the first two lines are As, creating a system that stops at the couplet before continuing.

AABBA

|

It rained the day I left my home |

a |

4 =A |

|

I hitched to Tulsa worn and soaked |

a |

4 =A |

|

I had to get away |

b |

3 =B |

|

To find another place |

b |

3 =B |

|

Nothing left to do but go |

a |

4 =A |

This feels pretty stable. Though it has two couplets, the shorter third and fourth lines keep it leaning a bit, like a limerick. The final A seems to stop rather than start a new sequence, as if it's simply referring back to the opening AA.

EXERCISE 38

Rewrite this AABBA with three-stress As and four-stress Bs. What difference does it make to the stability of the section?

AABBB

|

It rained the day I left my home |

a |

4 =A |

|

I hitched to Tulsa worn and soaked |

a |

4 =A |

|

I had to get away |

b |

3 =B |

|

To find another place |

b |

3 =B |

|

Where no one knew my name |

b |

3 =B |

This also feels pretty stable. It has resolutions at each couplet. The third B feels less like it's starting a new sequence and more like it's simply joining the party. There's nice spotlights on the fifth line.

EXERCISE 39

Rewrite this AABBB with three-stress As and four-stress Bs. What difference does it make to the stability of the section?

AAABB

|

It rained the day I left my home |

a |

4 =A |

|

I hitched to Tulsa worn and soaked |

a |

4 =A |

|

Salvation took the open road |

a |

4 =A |

|

I had to find a place |

b |

3 =B |

|

Where no one knew my name |

b |

3 =B |

This feels strangely stable. It should be crying out for another B, but it doesn't seem to. It's as though the feel of the couplet interferes with the request the sequence makes for two sets of three to create an AAABBB sequence. Perhaps it's having to move to an odd-numbered B that softens the push forward.

If you kept the line lengths and only rhymed the last two lines, it would float a lot more, and you'd get something like Gary Burr's “Can't Be Really Gone”:

|

Her hat is hanging by the door |

x |

4 |

|

The one she bought in Mexico |

x |

4 |

|

It blocked the wind and stopped the rain |

x |

4 |

|

She'd never leave that one |

a |

3 |

|

So she can't be really gone |

a |

3 |

A six-line version of AAABB would feel more balanced:

|

It rained the day I left my home |

a |

4 =A |

|

I hitched to Tulsa worn and soaked |

a |

4 =A |

|

Salvation took the open road |

a |

4 =A |

|

I had to find a place |

b |

3 =B |

|

Where no one knew my name |

b |

3 =B |

|

To start my life again |

b |

3 =B |

EXERCISE 40

Rewrite the AAABB example with three-stress As and four-stress Bs. What difference does it make to the stability of the section?

Groups With Three Matching Elements

Listed from most stable to least stable, these structures are groups with As, Bs, and Cs. Technically, any unmatched A, B, or C should be called an X. I think it's clearer here if we don't use Xs.

In the first group, the first two lines are different, creating forward motion.

ABCAC

|

It rained the day I left my home |

a |

4 =A |

|

I had to get away |

b |

3 =B |

|

I had to find a place where I could breathe |

c |

5 =C |

|

Salvation on the open road |

a |

4 =A |

|

Where I could finally find a little peace |

c |

5 =C |

Line four suggests that a sequence is taking shape: ABCABC. Then you get the closing element immediately. To the degree that line four raises expectations that B will be matched, line five fools you, thus creating deceptive closure. You get very strong spotlights at line five.

ABCBC

|

It rained the day I left my home |

a |

4 =A |

|

I had to get away |

b |

3 =B |

|

I had to find a spot where I could breathe |

c |

5 =C |

|

Where freedom rules the day |

b |

3 =B |

|

Where I could finally find a little peace |

c |

5 =C |

This is stable, and it seems to carry a little milder surprise at line five than ABCAC. You don't hear the sequence starting again at line four with an A, so it doesn't direct you forward as strongly. But once you hear B, the sequence kicks in, even though it's “out of sequence.” Another deceptive closure.

EXERCISE 41

Choose either ABCAC or ABCBC and target to a title from the unrhymed line. Construct a title that matches the unmatched line in both rhythm and rhyme. Target an inner vowel of the title line rather than the end rhyme.

ABCBB

|

It rained the day I left my home |

a |

4 =A |

|

I had to get away |

b |

3 =B |

|

I had to find a spot where I could breathe |

c |

5 =C |

|

Where freedom rules the day |

b |

3 =B |

|

Where peace has come to stay |

b |

3 =B |

You can feel the effect of the longer C line on the motion if you compare it to this:

|

It rained the day I left my home |

a |

4 =A |

|

I had to get away |

b |

3 =B |

|

To find a spot to breathe in |

c |

3+ =C |

|

Where freedom rules the day |

b |

3 =B |

|

Where peace has come to stay |

b |

3 =B |

The longer “C” line “sticks out,” calling attention to itself, diminishing the feeling of XAXA's expected closure, and making line four float just a tad. When we shorten the “C” line, the structure really closes.

The shorter C brightens the spotlights on line five by allowing line four to resolve solidly.

ABCAA

|

It rained the day I left my home |

a |

4 =A |

|

I had to get away |

b |

3 =B |

|

I had to find a place where I could breathe |

c |

5 =C |

|

Salvation on the open road |

a |

4 =A |

|

Nothing left to do but go |

a |

4 =A |

This feels unstable. It feels like it should continue forward, perhaps to something like:

|

Spend my hours to see what I could see |

c |

5 =C |

Again, the arrangement of line lengths here can change how it feels. Consider:

|

It rained the day I left my home |

a |

4 =A |

|

I had to get away |

b |

3 =B |

|

To find a place to shelter |

c |

3+ =C |

|

Salvation on the open road |

a |

4 =A |

|

Nothing left to do but go |

a |

4 =A |

EXERCISE 42

Describe how the shortened line in the previous example affects the structure's motion.

ABCAB

|

It rained the day I left my home |

a |

4 =A |

|

I had to get away |

b |

3 =B |

|

I had to find a place where I could breathe |

c |

5 =C |

|

Salvation on the open road |

a |

4 =A |

|

Where no one knew my name |

b |

3 =B |

Unstable. This one pushes forward pretty hard, to something like:

|

Spend my hours to see what I could see |

c |

5 =C |

Even with a shortened third line:

|

It rained the day I left my home |

a |

4 =A |

|

I had to get away |

b |

3 =B |

|

To find a place to shelter |

c |

3+ =C |

|

Salvation on the open road |

a |

4 =A |

|

Where no one knew my name |

b |

3 =B |

It still wants to move to:

|

To lose this helter skelter |

c |

3+ =C |

That's the power of sequence.

Though, mathematically, there are more possible combinations of five lines, this should more than suffice to increase your awareness of structural motion.

COMBINATIONS OF SIX LINES

ABCABC

|

I hitched to Tulsa worn and soaked |

a |

4 =A |

|

I had to get away |

b |

3 =B |

|

Miles to go, no promises to keep |

c |

5 =C |

|

She stared at me before she spoke |

a |

4 =A |

|

Without a word to say |

b |

3 =B |

|

She led me off to bed and off to sleep |

c |

5 =C |

This sequence moves relentlessly forward to a satisfying and resounding resolution at line six. It's the six-line version of common meter, working according to the principle of sequence.

ABABAA

|

I hitched to Tulsa worn and soaked |

a |

4 =A |

|

I had to get away |

b |

3 =B |

|

The waitress stared before she spoke |

a |

4 =A |

|

Then asked if I could stay |

b |

3 =B |

|

She vanished like a puff of smoke |

a |

4 =A |

|

I heard the chimes and then I woke |

a |

4 =A |

This closes after line four (ABAB), with a final couplet finishing it off. It's very stable, especially when the couplet matches one of the elements of the quatrain.

ABABCC

|

I hitched to Tulsa worn and soaked |

a |

4 =A |

|

I had to get away |

b |

3 =B |

|

She stared at me before she spoke |

a |

4 =A |

|

Without a word to say |

b |

3 =B |

|

She led me off to bed and off to sleep |

c |

5 =C |

|

No miles to go, no promises to keep |

c |

5 =C |

This also stops after line four (ABAB), with a final couplet closing it down. Very stable. The final couplet decelerates a bit with the longer lines, but makes up for it with the immediate (and thus accelerating) rhyme.

AABAAB

|

I hitched to Tulsa worn and soaked |

a |

4 =A |

|

A little bent, a lotta broke |

a |

4 =A |

|

Miles to go, no promises to keep |

b |

5 =B |

|

She stared at me before she spoke |

a |

4 =A |

|

And presto in a puff of smoke |

a |

4 =A |

|

She led me off to bed and off to sleep |

b |

5 =B |

Another solid citizen. It's a favorite structure of Leonard Cohen's. It doesn't push forward as hard as ABCABC, since the opening couplet stops the section. It's also harder for sequence to kick in, though it's in full force at the end of line five.

EXERCISE 43

Rewrite AABAAB with B=3 stresses. Is there a difference in how the section feels?

ABABAB

|

I hitched to Tulsa worn and soaked |

a |

4 =A |

|

Stopped to grab a bite |

b |

3 =B |

|

A little bent, a lotta broke |

a |

4 =A |

|

A half a dollar light |

b |

3 =B |

|

She stared at me before she spoke |

a |

4 =A |

|

And offered me a ride |

b |

3 =B |

Another solid citizen, though the final AB might clear its throat a bit, wondering whether the larger ABAB sequence will be matched again to make ABABABAB. So, just a touch of instability — looking forward to another AB.

ABBABB

|

With miles to go and promises to keep |

a |

5 =A |

|

I hitched to Tulsa worn and soaked |

b |

4 =B |

|

A little bent, a lotta broke |

b |

4 =B |

|

Without a bed without a place to sleep |

a |

5 =A |

|

She stared at me and when she spoke |

b |

4 =B |

|

My past became a puff of smoke |

b |

4 =B |

This feels stable, though we might add another line, something like:

|

I felt my spirit finally breaking free |

a |

3 =A |

With this added A, it still feels stable, perhaps more stable than the six-line section. Interesting, those line lengths.

But look what happens if we shorten the As:

|

With promises to keep |

a |

3 =A |

|

I hitched to Tulsa worn and soaked |

b |

4 =B |

|

A little bent, a lotta broke |

b |

4 =B |

|

Without a place to sleep |

a |

3 =A |

|

She stared at me and when she spoke |

b |

4 =B |

|

My past became a puff of smoke |

b |

4 =B |

It feels a bit more solid. Again, it shows the power of line lengths. The challenge with this structure is that it doesn't establish sequence, and thus doesn't raise much expectation, giving it a tendency to float.

ABABBA

|

I hitched to Tulsa worn and soaked |

a |

4 =A |

|

Stopped to grab a bite |

b |

3 =B |

|

A little bent, a lotta broke |

a |

4 =A |

|

A half a dollar light |

b |

3 =B |

|

She offered me a ride |

b |

3 =B |

|

And vanished in a puff of smoke |

a |

4 =A |

I like how this one plays tricks. Two unexpected closures, but in reverse order, creating a nifty surprise to support her vanishing act. Neat.

At this point, because you've done the exercises and understand the principles of motion, you should be able to construct all sorts of sections, both stable and unstable, using whatever number of lines you need to say what you have to say.

You're an expert at assessing and controlling motion. Now use that skill to create motion supporting your lyric's message. Have fun.