PROLOGUE

THE JOURNEY AHEAD

We lost a couple of old trees in our yard a few years back, big ornamental pears brought down not by lightning or wind but by their own structural weakness. These trees have a Y structure where two central branches push against one another, and over time the trees undermined themselves, eventually splitting apart. We mourned those trees and wondered what to replace them with. But within a few months, the little magnolia that had seemed so small beneath one of them shot up. It’s filled out that space magnificently now. Where the other tree once stood, we can grow flowers in places we couldn’t before. Sometimes when you lose something you think you need, life surprises you. What comes next turns out to be unexpectedly good. That may be the case with our economy. There’s a lot that’s breaking down now, a lot of financial and ecological upheaval—not because crises are coming out of nowhere and hitting us but because the structure of industrial-age capitalism is causing them. It’s a good time to open our minds to new things sprouting up.

Here’s one. In Cleveland, Ohio, a city experiencing the bleakest form of economic decay, a new model of worker-owned business is taking shape, starting with the Evergreen Cooperative Laundry. At this green laundry—supported by stable contracts with anchor institutions such as hospitals and universities—employees buy into the company through payroll deductions and can build a $65,000 equity stake over eight or nine years. As work supervisor Medrick Addison says, “Maybe through Evergreen things that I always thought would be out of reach for me might become possible.” Other companies in the Cleveland project include Ohio Cooperative Solar, expected to employ 100, and Green City Growers, likely to become the largest urban food-producing greenhouse in the nation. Organizers envision a group of ten companies creating 500 jobs over five years—in a city where the poverty rate is above 30 percent. Efforts are underway to spread this model to other cities.1

It’s hard to talk about hope in these troubled times, but hope is what we’re called to. My sense is that a new kind of economy—one that serves the many rather than the few, one that’s ecologically beneficial rather than harmful—is sprouting in little (and not so little) experiments here and there, in ways that weren’t possible before. A lot of us don’t see this, because we don’t believe good things might come from the messes we’re in. In the global capitalist economy, many of us are grim adherents of the TINA school of thought: There Is No Alternative.

My sense is that there is an alternative, and that the reality of it is farther along than we suppose. When we can’t see this, it’s because we’ve left no room for it in our imagination. If it’s hard to talk about, it’s because it doesn’t yet have a name. I suggest we call it the generative economy. It’s a corner of the economy (hopefully someday much more) that’s not designed for the extraction of maximum financial wealth. Its purpose is to create the conditions for life. It does this through its normal functioning, because of the way it’s designed, the way it’s owned—like an employee-owned solar company.

Some may not believe this kind of economy is possible, except on the fringe. But in this book, I don’t ask you to believe anything. Instead, I invite you to come along and see.

![]()

As I fly into Copenhagen Airport, the plane banking low over the harbor, I see seven wind turbines standing there in the waters offshore, their white blades gleaming in the sun, turning in syncopation. This is Lynneten Wind Farm, with an ownership architecture as innovative and hopeful as its physical architecture. Three of these turbines are owned by a local utility, four by a wind guild. Denmark’s wind guilds were created by small investors who joined together to fund and own wind installations, with no corporate middleman. Denmark today generates one-fifth of its electric power from wind, more than any other nation. Many observers credit that success to the grassroots movement of the wind guilds.2 It’s an ecological success story made possible by the ownership designs behind it.

In late 2008, I awake one morning to news on the radio that global stock markets are in freefall, the heart-stopping 42 percent plunge that markets saw that year not yet at bottom. The funk that the international economy remains in today is descending like a black mood, like the tingly shock of opening a credit card bill after a spending spree. This is the day when I catch the bus to the Seaport World Trade Center in Boston to attend the annual meeting of the National Community Land Trust Network. Community land trusts (CLTs) are ownership designs in which individual families own their homes and a community nonprofit owns the land beneath a group of homes. This design reduces and stabilizes the price of homes while it prohibits speculative ownership. CLTs, I learn, have foreclosure rates one-tenth of those of traditionally owned homes.3 As attorney David Abromowitz says at the meeting, “It’s like a bomb went off and all the houses have been flattened, but there’s one well-built house still standing.” The metaphoric house still standing is the community land trust home. The reason is its ownership design.

On a brisk November day, I make the drive from Madison to nearby La Farge, Wisconsin, to visit the headquarters of Organic Valley and meet its ponytailed CEO, George Siemon. With more than $700 million in revenue, this organic dairy company was created to save the family farm. It’s owned by close to 1,700 farm families. These include the Forgues family, which at one time struggled to make ends meet. Today their farm supports two families with relative ease because of the high, stable price that Organic Valley pays its farmers for milk, cheese, and eggs. While other companies aim to pay suppliers as little as possible, this company aims to pay its suppliers as much as possible. The reason is that farmers own this company.

When Leslie Christian tells me of her idea for a new kind of corporation—later to be called a benefit corporation (B Corporation)—it’s on a long walk that we take together at the foot of the Rockies. A former Wall Street bond trader, Leslie has taken a post as president of a socially responsible investing firm, Portfolio 21 Investments, in Portland, Oregon, hoping to use finance as a tool in building a more humane economy. As part of her work, she creates a subsidiary with a new purpose baked into its corporate charter and bylaws. The company’s purpose is to serve many stakeholders—including employees, the community, the environment, and stockholders. Inspired by her, some young entrepreneurs start B Lab to promote aspects of the model. Within a few years, close to 500 companies become B Corporations, and a dozen states pass or are considering legislation to allow the formation of benefit corporations. Though the model is not without its critics, many business watchers talk about the benefit corporation as a potentially transformative new approach to ownership.4

In 2011, attorneys in every state of the United States begin filing lawsuits aiming to have the atmosphere declared a public trust—a commons, owned by all of us, deserving special protection. The suits are filed on behalf of young people, arguing that their future is threatened by climate change. If they achieve victory in even one case, it might create a ripple effect like that seen with gay marriage, where state after state follows. This could create leverage for legislation to rein in greenhouse gas emissions. It’s a new approach to reclaiming our economy for the common good, using the power of ownership.5

![]()

These journeys have a common thread: ownership. In a way that many of us rarely notice, ownership is the underlying architecture of our economy. It’s the foundation of our world. How ownership is framed is more basic to our daily lives than the shape of democracy. Economic relations define the tenor of our days: where we work for 40 hours (or more) each week or whether we work at all. How owners wield their power over companies determines whether we’re empowered or belittled by our work, how much anxiety we suffer over our debts, whether we’re able to own a home or be secure in retirement. Questions about who owns the wealth-producing infrastructure of an economy, who controls it, whose interests it serves, are among the largest issues any society can face. Issues of who owns the sky in terms of carbon emission rights, who owns water, who owns development rights, are planetary in scope.

The multiplying crises we face today are entwined at their root with the particular form of ownership that dominates our world—the publicly traded corporation, in which ownership shares trade in public stock markets. The revenue of the largest 1,000 of these corporations represents roughly 80 percent of global industrial output.6 Stripped of regulatory overlay, the design of these corporations is the bare design of capitalism.

As a way of organizing an economy, this model made a certain amount of sense when the industrial age was unfolding. The modern age might not have come to be, without the emergence of corporations and capital markets. But as we make the painful turn into a new era—characterized by climate change, water shortages, species extinction, vast unemployment, stagnant wages, staggering differentials in wealth, and bloated debt loads—the industrial-age model of ownership is beginning to make less sense. Getting our arms around this large issue can seem difficult. Unable to even approach it, politicians instead fixate on how to jumpstart the economy and get growth moving again. But it’s time to move beyond growth, to recognize that the economy as we once knew it will never return. Nor should it.

As the dominant form of ownership continues to spin off crisis after crisis in our time, alternative forms are at the same time emerging in largely unsung, disconnected experiments all over the world. We’re at the beginning of an unseen ownership revolution. In this book, I visit places where this hopeful future is welling up like cold springs. It’s a journey into the territory of the possible, a kind of advance scouting expedition for the collective journey of our global culture.

It’s a book about deep change. It’s about hope. It’s about the real possibility that a fundamentally new kind of economy can be built, that this work is further along than we suppose, and that it goes deeper than we would dare to dream. It’s about economic change that is fundamental and enduring: not greenwash or all the other false hopes flung in our faces for too long. The experiments I’m talking about are not silver bullets that will solve all our problems. They have flaws and limitations. But they nonetheless represent change that is fundamental and enduring because it involves ownership. That is to say, what’s at work is not the legislative or presidential whims of a particular hour, but a permanent shift in the underlying architecture of economic power.

A PERSONAL ODYSSEY

As significant as different patterns of ownership are, they’re hard to see, because they’re deep structures lying beneath the surface of things. I learned about the importance of ownership from my father, and it was a lesson he delivered not in words but with the arc of his own life.

I grew up in a family of eight children, raised fairly comfortably on my father’s single salary from the small business he owned in Columbia, Missouri. My maternal grandfather owned his own company, as did many of my uncles. When I was a child, no one in my extended family was rich. But we had what all families deserve and few today enjoy, which is economic security. The reason was that my parents owned things. They never saved much money, but they owned my father’s business, our house, and a few other pieces of real estate. It was enough that when my father died at the young age of 62, my mother was able to live at ease for decades without working outside the home. There was no shortage of emotional dysfunction in our household (including a good bit of Irish Catholic drinking and stormy tempers). But the economic security we enjoyed helped my siblings and me to mature into stability. In a visceral way, I experienced financial security as a form of nurturance, as vital as food or shelter—something that sustained me and allowed me to thrive.

If I saw the positive side of ownership as a child, I saw its negative side at Business Ethics, a magazine I cofounded in 1987 and where I served as president for 20 years. In that time, I watched corporations rewrite the social contract. I saw mass layoffs shift from something companies did in a dire emergency to become ordinary practice. I watched companies I once admired hire union-busting consultants. In five short years, I saw the number of Washington lobbyists double.7 I watched wages flatline and the proportion of taxes paid by corporations fall. When the scandals at Enron, WorldCom, Adelphia, Parmalat, and other companies broke out, it became clear that cooking the books had become disturbingly widespread.

At every turn, companies claimed to be acting in the interests of their owners, their shareholders. Ironically, the owners supposedly demanding those acts were us, all of us with investing portfolios holding stock in corporations, all of us who have children attending colleges with endowments, all of us who support churches, museums, and nonprofits that rely on donations paid for from financial holdings.

![]()

We’re all tangled up in our system’s ownership designs. And we’re all tangled up in the messes they’ve left in the economy and the biosphere. Because we’ve yet to grasp how the crises we face are symptoms of deep structural problems, what lies ahead may be worse still.

Wanting to help in the search for alternatives, a number of years ago I sold Business Ethics and moved to the Tellus Institute in Boston. There, my colleague Allen White and I cofounded the initiative Corporation 20/20, bringing together hundreds of leaders from business, finance, law, government, labor, and civil society to explore alternatives to the dominant corporate form.8 That work confirmed my growing conviction that ownership is the root issue. I remember a particular moment when it snapped into focus for the whole group.

It was 3 p.m. on a Friday and the energy in our group was flagging. Seated around the conference table were 30 of the most innovative thinkers I knew, all struggling to stay awake. If the topic we’d come together to explore, redesigning capitalism, was a worthy subject, by late on a Friday it was a boring one. We were in day three of our time together, in the third of these gatherings. It had begun to feel like we were half-crazed survivors dragging ourselves through one jungle of impenetrable concepts after another: stock options, Delaware law, fiduciary duty, and more. I looked around the table, thinking, we’ve got to get these people into a break. They need coffee, fast.

Then someone uttered a simple statement. I wish I could remember who said it. But I’ll never forget what he said: “Ownership is the original system condition.”

There was a pause, the nodding of many heads. Some chatter of agreement. Then the facilitator called for a break. Yet no one left the room. No one even touched the cookies wheeled in at the back. You would have thought the coffee had been delivered intravenously. The room was so alive with animated talk that it was as though we’d been huddled in a dark cellar, and someone had opened a door and thrown on the lights.

The energy in the group was back because we’d touched the root issue that defines corporations and capital markets today. It’s ownership.

Ownership is the gravitational field that holds our economy in its orbit, locking us all into behaviors that lead to financial excess and ecological overshoot.

During my work with Corporation 20/20, my premise was that the answers were about redesigning corporations. But then my Tellus work shifted to a new project with the Ford Foundation involving rural communities, and I began looking at forms of ownership that didn’t involve corporations at all.9 I studied shared ownership and governance of homes, farms, forests, wind farms, fishing rights, and more.

As I discovered more and more models, I realized that I’d found my way to the edge of a movement much larger than corporate redesign. Something is emerging that goes to the root issue, the institution with which civilized economic life began, back beyond the age of industry in the age of agriculture. That root issue is ownership. We are witnessing its spontaneous evolution.

HARBINGERS OF THE NEW

New models are emerging today, not from the head of some new Adam Smith or Karl Marx but from the longing in many hearts, the genius of many minds, the effort of many hands to build what we know instinctively that we need.

In both the United States and the United Kingdom, there’s burgeoning interest in social enterprises, which serve a primary social mission while they function as businesses—like Greyston Bakery in Yonkers, New York, an $8 million profit-making business started by Zen monks with an aim of creating jobs for the homeless.10 Community development financial institutions (CDFIs)—which in the United States provide financial services to underserved low-wealth communities—are growing by leaps and bounds. In little over a decade, assets have climbed from $5 billion to $42 billion, with new funds coming from depositors, investors, and government grants.11

Emerging experiments with catch shares, ownership rights in marine fisheries, have been found to halt or reverse catastrophic declines in fish stocks.12 Conservation easements now cover tens of millions of acres, allowing land to be used and farmed even as it’s protected from development, preserving it for future generations both human and wild.13 There’s a growing movement to protect the commons, honoring areas of our common life that need shielding from market forces. And there’s the viral world of entities like Wikipedia, owned by no one and run collectively.

Revolutionary lawyers are busy crafting new models through law—like the community interest corporation, created in UK law.14 And the low-profit, limited liability company (L3C) in the United States, intended to facilitate more social investments by foundations. In the space of only a few years, this model has been enacted or come under consideration by nearly 20 states.15 And there’s the notable success of the Bank of North Dakota, the only state-owned bank in the United States, which in the initial financial crisis enjoyed record profits even as private-sector banks lost billions. Its unexpected resilience has led some 14 states to begin considering legislation to create their own banks.16 (State banks are not privately owned, but they do represent alternative ownership focused on the common good rather than on maximizing profits.)

In Quebec and Latin America, among other places, there’s a growing movement for the solidarity economy—consisting of cooperatives and nonprofits—which in Quebec has gained formal recognition and government funding as a distinct sector of the economy.17 And a surprising number of large corporations have adopted mission-controlled designs. Among these are the foundation-owned corporations common throughout northern Europe, such as Novo Nordisk, a Danish pharmaceutical company with $11 billion in revenue, as well as Ikea, Bertelsmann, and other large companies. Also included in mission-controlled designs are family-controlled companies with a strong social mission, such as S. C. Johnson and the New York Times.18

More exotic designs are also popping up, like Grameen Danone, a social business in which village women in Bangladesh sell yogurt through a joint venture between multinational yogurt maker Groupe Danone and Grameen Bank, the first microfinance lender. The enterprise is designed to improve the nutrition of the poor as it aims to pay investors a modest, 1 percent dividend.19

Two pioneers in the field of emerging economic architectures have received Nobel prizes—Muhammad Yunus, who founded Grameen Bank and helped create Grameen Danone, and Elinor Ostrom of Indiana University, who studies economic governance of the commons. She and her colleagues have found communities all over the world that have spontaneously devised effective ways to govern fish stocks, pastures, forests, lakes, and groundwater basins in ways that preserve rather than harm those ecosystems.20

Emerging ownership models are new members of an older family of designs that include cooperatives, employee-owned firms, and government-sponsored enterprises. In the UK, these include the John Lewis Partnership—the largest department store chain in the country—which is 100 percent owned by its employees and has an employee house of representatives in addition to a traditional board of directors.

As a class, these alternatives represent an emerging family of design. If industrial-age ownership is based on a monoculture model, emerging designs are as rich in biodiversity as a rainforest. Through studying these, grafting pieces of them together to create still more models, we just might create the greenhouse of design experimentation where the future of our economy could be grown.

These social architectures are harbingers of something profoundly new. They aren’t yet fully formed, not yet ready to serve as the framework of a new social order. But their growing profusion is a signal. It tells us that we’re entering one of the most creative periods of economic innovation since the Industrial Revolution. For what’s at work isn’t economic innovation as it’s usually meant, which is about better and better ways to make more and more money. This innovation is almost unimaginably more profound. It is a reinvention at the level of organizational purpose and structure. It is about creating economic architectures that are self-organized around serving the needs of life.

GENERATIVE VS. EXTRACTIVE OWNERSHIP

These models embody a coherent school of design—a common form of organization that brings the living concerns of the human and ecological communities into the world of property rights and economic power. It’s an emerging archetype yet to be recognized as a single phenomenon because it has yet to have a single name. Hannah Arendt observed that a stray dog has a better chance of surviving if it’s given a name. We might try calling this a family of generative ownership designs. Together they form the foundation for a generative economy.

In their animating intent and living impact, these ownership designs are aimed at generating the conditions where all life can thrive. From the Greek ge, generative uses the same root form found in the term for Earth, Gaia, and in the words genesis and genetics. It connotes life. Generative means the carrying on of life, and generative design is about the institutional framework for doing so. The generative economy is one whose fundamental architecture tends to create beneficial rather than harmful outcomes. It’s a living economy that has a built-in tendency to be socially fair and ecologically sustainable.21

Generative ownership designs are about generating and preserving real wealth, living wealth, rather than phantom wealth than can evaporate in the next quarter.22 They’re about helping families to enjoy secure homes. Creating jobs. Preserving a forest. Generating nourishment out of waste. Generating broad well-being.

These designs are in contrast to the dominant ownership design of today. To make the distinction clear, that design also needs a name. We might call it extractive, for its focus is maximum physical and financial extraction. Our industrial-age civilization has been powered by twin processes of extraction: extracting fossil fuels from the earth and extracting financial wealth from the economy. But these two processes are not parallel, for finance is the master force. Biophysical damage may often be the effect of the system’s action, yet extracting financial wealth is its aim.

As we begin to build what economist E. F. Schumacher called an “economy of permanence” on our fragile planet, maximum financial growth will be ill-suited as a guiding purpose. In generative design, we see in practical detail how a different goal can be at the core of economic activity. Generative design shows us that a transformative shift has already begun and suggests how it might be amplified.

OWNERSHIP AS A REVOLUTIONARY FORCE

“There’s a movement going on that doesn’t know it’s a movement,” attorney Todd Johnson said to me (he’s one of those revolutionary attorneys devising new designs). What’s under way is an ownership revolution. It’s about broadening economic power from the few to the many and about changing the mindset from social indifference to social benefit. We’re schooled to fear this shift, to think there are only two choices for the design of an economy: capitalism and communism, private ownership and state ownership. But the alternatives being grown today defy those dusty 19th-century categories. They represent a new option of private ownership for the common good. This economic revolution is different from a political one. It’s not about tearing down but about building up. It’s about reconstructing the foundation of ownership on which the economy rests.

For centuries, moments of crisis have been times when people turned to alternative ownership designs for protection. The first modern cooperative, the Rochdale Society, was formed in England in the 1840s, when the Industrial Revolution was forcing many skilled workers into poverty. The Rochdale Pioneers were weavers and artisans who banded together to open the first consumer-owned cooperative, selling food to workers who otherwise couldn’t afford it. The cooperative model they created has spread to more than 90 nations and now involves close to a billion members.23

During the Great Depression in the United States, the Federal Credit Union Act—ensuring that credit would be available to people of small means—was intended to help stabilize an imbalanced financial system. Today the assets of credit unions total more than $700 billion. Since the financial crisis of 2008, these customer-owned banks have added more than 1.5 million members. A key reason is that in the initial crisis, their loan delinquency rates were half those of traditional banks.24 In Argentina in 2001, when a financial meltdown created thousands of bankruptcies and saw many business owners flee, workers kept showing up to work. With government support, they took over more than 200 firms and ran these empresas recuperadas themselves.25

In our time, the need for alternative kinds of ownership is more critical than ever, for the path ahead forks. The path of business as usual points toward a fortress world, a place where the wealthy few retreat into enclaves of luxury and security while most struggle in fear and want. The path of transformation points toward a new economy, a potentially generative economy that yields prosperity both sustainable and shared.26 Whichever world we choose, it will be ownership and financial architectures that give it its essential shape.

When I give talks about generative ownership design, people sometimes say, “It would be nice, but how can we get there?” The answer, I suspect, will be twofold. We’ll need a pincer movement: one arm moving to rein in corporate abuse and reform corporate governance at existing corporations, the other arm moving to develop generative alternatives.27 Both kinds of effort are necessary. But it’s the second strategy—promoting alternatives—that today lacks coherence and momentum. It’s difficult to unite and work for deep change when we lack a clear, shared vision of the kind of economy we truly want and a simple understanding of the designs that make it function.

The development of alternatives relies, initially, on emergence. As organizational change theorist Meg Wheatley has written, emergence is about connecting with people who share a common vision. This is how local actions spring up, connect through networks, and strengthen into communities of practice. With little warning, emergent phenomena can appear—like the rise of the organic and local food movements. Ultimately, a new system can emerge at greater scale: not magically, but through a combination of unplanned emergent activities and later more focused efforts.28

I explore emergence in chapter 8, “Bringing Forth a World,” and offer more thoughts on change strategies throughout the book—particularly in the epilogue. But my aim isn’t to create a roadmap of how to get from here to there. My focus is on there. My quest is for a vision and language, at once practical and profound, that might guide us in the tumultuous days ahead.

THE PATTERNS OF LIFE

If most of us understand the design of democratic power, we don’t understand economic power. We don’t understand the design of ownership. And we need to. What has yet to be done—and what I attempt here—is to devise a simple pattern language to describe the designs that underlie and unify seemingly disparate models. As architect Christopher Alexander has said, we need to discover how to talk about patterns in a way that can be shared. This means naming them. “We must make each pattern a thing so that the human mind can use it easily,” he wrote in The Timeless Way of Building.29 (I return to Alexander’s work in part 3.)

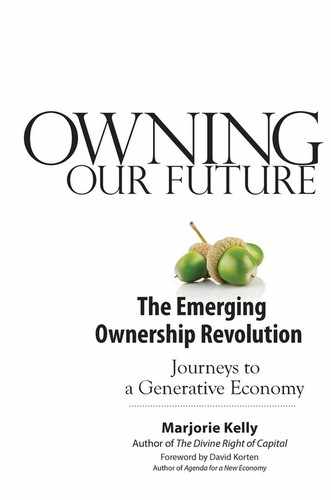

I’ve found five essential patterns that work together to create different kinds of ownership: purpose, membership, governance, capital, and networks. These can be used in extractive ways—aimed at extracting maximum financial wealth in the short term. Or they can be used in generative ways—aimed at creating a world where all living beings can flourish for generations to come. If new models remain to be created, many of the underlying design patterns we need are already here and can be combined in novel ways.

![]()

Extractive ownership has a Financial Purpose: maximizing profits. Generative ownership has a Living Purpose: creating the conditions for life. While corporations today have Absentee Membership, with owners disconnected from the life of enterprise, generative ownership has Rooted Membership, with ownership held in human hands. While extractive ownership involves Governance by Markets, with control by capital markets on autopilot, generative designs have Mission-Controlled Governance, with control by those focused on social mission. While extractive investments involve Casino Finance, alternative approaches involve Stakeholder Finance, where capital becomes a friend rather than a master. Instead of Commodity Networks, where goods are traded based solely on price, generative economic relations are supported by Ethical Networks, which offer collective support for social and ecological norms. Not every ownership model has every one of these design patterns. But the more generative patterns are employed, the more effective the design.

In key ways, this book is a continuation of my previous one, The Divine Right of Capital. That book looked at the myths upholding the rights of capital, particularly the myth that wealth holders have needs that come before everyone else’s needs. It also explored principles of economic democracy. In the decade since it was published, the ownership structures of our economy—the intertwined institutions of corporations and capital markets, and the perpetual growth and rising profits they require—have contributed to unprecedented new crises, such as climate change. It no longer seems sufficient to speak of economic democracy as the solution.

A more appropriate frame of reference may be the living system of the planet. The ultimate patterns that all systems must employ are living patterns—the patterns of organization that nature has evolved to support life. Systems thinking, which arose in physics and is spreading to other disciplines, offers a robust language for speaking about living patterns and processes. It’s a language that applies equally to biological systems and social systems. Through systems thinking, we can see that the task of redesigning ownership is part of the larger task of bringing human civilization into harmony with the earth.

We know the next economy will require things like wind turbines, limits on carbon emissions, and sustainably managed forests. The questions that remain largely unanswered are about who will own these, who will control them, and who will flourish in the world they create. We need innovation not only in physical technologies but also in social architectures.30 If physical technologies are about the what of the economy, social architectures are about the who: who will make economic decisions, and how, using what kinds of organizing structures? Social architectures are the blueprints of human relations, how we organize ourselves to do things. Will we continue to rely on economic architectures organized around growth and maximum income for the few? Or can we shift to new architectures organized around keeping this planet and all its inhabitants thriving? This book is a quest for answers.

MAPPING THE JOURNEY AHEAD

In part 1, I trace how extractive design in one industry, the mortgage industry, drove toward financial overshoot and collapse. I start with the foreclosed house that a friend of mine was trying to buy, for which he couldn’t find any owner to whom he could make an offer. I follow this thread to the New York Stock Exchange, and into other worlds of financial engineering, to trace what went wrong in the social architecture of ownership. Ultimately, I set out to find the couple that the house once belonged to, to see how the subprime mortgage collapse impacted the life of one family.

In part 2, I look for the seeds of a new value system that might give rise to a new economy. I visit experiments in ownership of the commons: the Maine lobster industry, community forests, community wind, a cohousing community, and others. Embodied in these ownership models are values of sustainability, community, and sufficiency (the idea that after the pursuit of “more” comes the recognition of “enough”). These may be the values that one day replace the pursuit of limitless financial wealth, the focus on individualism, and the insistence on maximum growth, which remain embedded in today’s ownership designs.

If part 1 is about the breakdown of ownership, and part 2 is about the ground of its evolution, part 3 looks at design patterns that are bringing generative ownership to life on a broad scale. Each chapter takes up one key pattern of generative design, looking at how these combine to keep social mission alive over time. I’ve seen many companies that once were generative lose their social mission when they grow large or when the founder departs. In part 3, I search for successful, substantial companies that have solved the “legacy problem”—keeping social legacy alive long after the founder is gone. I tour the employee-owned John Lewis Partnership in London. I visit foundation-owned Novo Nordisk in Denmark, a pharmaceutical with production based in Kalundborg, home to a famed example of “industrial symbiosis,” where this company’s waste becomes food for the ecosystem. Among other expeditions, I revisit finance, talking with a couple of investing advisers to see how I can use my own small investment portfolio to help in the transformation.

My hope is that these journeys will be of interest both to specialists and to the general, thoughtful reader. For those deeply immersed in ownership design, the simple design patterns I see at work might help bring coherence to what has been a disconnected field. For others, these journeys might help answer the questions that bedevil us: How did a civilization as advanced and fiercely intelligent as our own manage to get things so catastrophically wrong? How, in other words, did we get here? And where might we be heading in the most hopeful, if not the most likely, scenario? What kind of economy could we create if we turned the emerging ownership revolution into a concerted, organized social force?

![]()

If ownership talk feels unfamiliar, it did to me too when I began dreaming of launching Business Ethics a quarter century ago. I was in my early 30s then, and owning my own company felt so grown-up, so beyond me. It was something in the realm of the fathers, not in my realm as a young woman. I remember a dream I had one night of entering a building—a church, a bank, or in dream logic somehow both—where I saw men standing behind a railing, murmuring among themselves. A barrier separated me from them, like the communion railing separating the congregation from the priest, marking off a territory where only the banker-priests could enter. I stepped inside that rail. And to my surprise, no one minded. They acted as though I belonged. And I did. Moving more boldly, I began to dream of remodeling the space, throwing out a wall, widening the room, removing the barrier, allowing more to enter. I awoke exhilarated.

Having wandered around in the architecture of ownership a good long time now, I want to invite others in. Ownership is the ultimate realm of economic power. We all belong there—in the same way that we all belong in the halls of democracy. It’s time for us to own this place we call an economy and stop leaving it to the banker-priests. When more and more of us become comfortable entering the seemingly forbidden space of ownership—daring to dream together of remaking it—that’s when we will truly own our future.

THE DESIGN OF ECONOMIC POWER

The Architecture of Ownership