FIVE

COLLAPSE

The Eroding Middle-Class Base

That reminded me: What happened to the Haroldsons? To bring this journey to a close, I needed to find out what happened to the family on the other side of the ownership equation—not the financial side but the real side. It was time to try again to track them down.

When I’d previously searched for the Haroldsons on the Web, I’d found so many people with similar names that I couldn’t call them all. I thought a call out of the blue might not do much good, anyway. I hoped for a personal introduction. Checking back with Orion, I get the name of someone he knows who owns a two-flat across from the Haroldson house, a woman I’ll call Toni. When I phone her, she picks up immediately. “I never knew the Haroldsons because they’d already left when I bought my house,” she tells me. But she can put me in touch with a Jamaican family, Luis and Alva, who lived next door to the Haroldson house for 25 years. She mentions another neighbor, a retired gentleman, Giuseppe, who’s lived on the street for 30 years.* “Call me in a few days,” she says.

When I do, there’s good news. Luis and Alva have a niece who is friends with the Haroldsons’ grandson. They’ll be seeing him soon and will pass along word that I want to talk. I ask Toni if she has a phone number for the Haroldsons. “We’re working on it,” she says brightly. How about a number for Luis and Alva? Toni laughs and says she never needed it. “You just have to show up and knock on their door.”

A few weeks and a few unanswered calls later, I finally catch up with Toni again by phone. As soon as I identify myself, she launches in: it’s a busy day, she’s on her way out the door, she’s losing her tenant, she has calls to return. “Listen, honey, I’m not going to be able to help you,” she says, her tone kindly but exasperated. If I want to know more about the Haroldsons, it looks like I’ll have to show up at Luis and Alva’s and knock. Later that week, that’s what I do.

![]()

From the Stonybrook T stop, I walk the few blocks and mount the pebbly concrete steps, seeing a “For Sale” sign in the yard of 56 James Court. “New renovation,” it says. The porches have been rebuilt, the trim painted white, new gray siding added, double-pane windows and air conditioners installed. In the yard—freshly mown now—a dozen tiny shrubs nestle in fresh mulch. Walking to the back, I peer under the porch to find it swept clean, no one living under there anymore. I tap on the siding. Plastic. The firm listing the home is in the business of “real estate, mortgages, insurance”—one of the holding companies in what Kevin Phillips called the FIRE sector (finance, insurance, real estate).

Heading next door, I climb the steps and ring the bell. Footsteps sound in the hall.

“What do you want?” a man’s voice asks.

I find myself speaking to a peephole. I say that his neighbor Toni referred me, and I’m researching the foreclosure of the house next door.

“No one lives there,” he says quickly. It’s the previous owners I’m looking for, I begin, but he cuts me off. “It’s not my house. I don’t have nothing to say about it.” I hear footsteps retreating.

Standing there holding the Whole Foods bag with the chocolate-dipped gingerbread cookies I’d planned to offer—over tea in a sunny kitchen, I’d imagined—I begin to feel vaguely ridiculous. Yet undaunted. Perhaps at Giuseppe’s I’ll have better luck.

I find the second-floor flat where he lives and knock. Then knock again. Through the glass door, wooden stairs gleam under fresh polish, and at the top of them a dog arrives, barking. I knock once more and then turn to leave. As I let myself out the gate, I turn and see an older man peering at me from the second-floor window. Then he’s gone.

Down the street, I run into a young woman in blond dreadlocks coming out of Toni’s yard with a small boy in tow—apparently the tenant moving out. I raise a hand and she stops to chat, telling me she’s lived there less than a year.

“The neighborhood has become increasingly violent,” she says. There’ve been a dozen shootings in the last year.

“Were they killings?”

“At least four were. We’re leaving, moving to Florida.”

As she heads off, the reality of Toni’s situation sinks in for me more deeply than before. This landlord and homeowner is under enormous strain, as is her entire neighborhood. She might be at risk of losing her home. It seems less urgent, somehow, to trouble her yet again about a former neighbor she’s never met. I leave a package of chocolates atop the rusted mailbox on Toni’s cluttered porch, with a note thanking her for her help, and set off for the T stop.

THE COLLAPSE OF A MIDDLE-CLASS LIFE

Out of ideas about how to proceed, I turn to a colleague with a better understanding of public records and ask him to undertake a deeper search for me. Before long, a document arrives. It has the Haroldsons’ new address and, wonder of wonders, Michael Haroldson’s phone number. There’s more. My friend has found that the Haroldsons are both in their 60s, and Michael is a retired firefighter. Realizing that I won’t get the personal introduction I’d hoped for, I send a letter off, explaining who I am and what I’m researching, asking if they’re willing to talk. A week or so later, I phone and leave a message. And wait.

Enough time passes that I give up. Then one day the phone rings. “This is Michael Haroldson,” the gentleman says, in a voice like a baritone in a gospel choir. Yes, he’s willing to meet. He suggests after ten some morning, because by then the four kids they have running around will be off to school.

Their new place turns out to be just 13 miles south on Highway 107, in a large apartment building. After parking my car, I get buzzed in by a security guard, who points me toward their unit—down a maze of corridors freshly carpeted in institutional beige. Michael meets me at the door, and Helen soon joins us. Both are youthful looking, though the circles under Helen’s eyes show strain. I soon see one reason why, as a bright-eyed toddler wakes up from his nap, and Helen carries him in to join us.

“He’ll be 11 months tomorrow,” Michael announces.

“Well, happy birthday,” I say, as the little one climbs up on the couch with me. He’s one of four grandchildren the Haroldsons are raising, ranging up to age 12. As I hand Michael the box of fresh cookies I’ve brought, he talks about how they’ve come to find themselves in the role of caregivers (asking me not to share some of those family details). We move on to talking about Michael’s career as a firefighter. I’ve done some Google searching and discovered that he received a Distinguished Service Award.

“Yes,” he recalls. “There’d been a stabbing in front of my mother’s house, and two kids were lying there, bleeding. I went to work on both of them, with no gloves, trying to suppress the bleeding. I saved one of the kids. The other died.” The killer, he found out later, was standing across the street the whole time, watching him. He’d gotten other awards as well, he says, including firefighter of the year.

Helen, too, is in a helping profession. She’s a nurse’s assistant at a hospital where she’s worked for 34 years. Because of the kids, she now works just two days a week. In sum, this is a couple, retired and semiretired, raising a second family on a firefighter’s pension plus dribs and drabs from part-time work. Their situation has its seeds back at 56 James Court, when they found themselves unexpectedly responsible for two grandchildren.

“You lived in that house on James Court for 13 years,” I begin.

“Almost 14,” Michael replies. He moves unself-consciously into talking about how they lost the house, why they cycled through five mortgages in five years. Their son had needed a place to live and moved into the rental unit downstairs. He was out of work. Michael and Helen ended up supporting that family.

“When the kids needed things, it was expensive,” Michael says. So they refinanced the home to pay off some bills. And then did it again. And again.

“When you refinanced, they gave you a check. Do you remember for how much?” I ask.

“It wasn’t that much,” Michael says. “Maybe $14,000. Between $9,000 and $14,000. We did that four times, I think it was.”

If his recollection is right, they pulled perhaps $50,000 or so in cash out of the house. Yet their mortgage debt climbed by an additional $250,000. That told me the mortgages that the Haroldsons took on likely contained abusive terms. My research showed that, in general, subprime mortgages often contained features like teaser interest rates that quickly reset to double or triple the amount, prepayment penalties of $8,000 to $10,000 or more if loans were paid before their full term, high charges for brokerage fees, and monthly payments often higher than a family’s total income.1 Before our meeting, I’d estimated that with these charges, as well as closing costs of maybe $5,000 per mortgage, the five mortgages that the Haroldsons went through in five years could easily have extracted fees totaling $100,000 out of the home’s equity. It sounded as though it might have been a lot more than that.

“Were there prepayment penalties involved?” I ask. They both look at me blankly. “Were there variable interest rates, the kind that can go up over time?”

“They went over things briefly, but it wasn’t fully explained,” Michael tells me. “We would think we’d be getting a lower interest rate, but instead it went up.”

“You don’t know why the rates went up?”

“No.”

“Were you aware that your total debt was going up?”

“We were just aware that our monthly payments were going up,” he says. The payments started at around $1,800 a month and then went to $2,400, then $2,800, $3,200, $3,300. “It was overwhelming,” he says.

I ask about Aegis, where they’d gotten three mortgages. Michael says they went to the company’s office and spoke to a person who seemed nice. “He was young and a fast talker,” he adds. They dealt with him more than once. “He told us, don’t worry about it, we can do this, we can do that. Basically, he was saying what I wanted to hear.”

“Did anyone tell you that when you refinance so quickly, every 12 months or so, you’re losing a lot of money?”

“No. When we’d have financial difficulties, we’d call them up. Once we got maybe $5,000.” Michael leans forward and his voice quickens. “But even $5,000, with the kids, would come in handy.”

It was little wonder that mortgage brokers had been eager to write subprime mortgages. The profit potential was enormous, and the hands ready to grab it were lined up all the way to Manhattan. As Charles Morris described it, those brokers “were creating ‘product’ for an assembly line that flowed from mortgage banks to the CDO machines, run by firms like Merrill Lynch and Citigroup—swelling Wall Street bonus checks.”2

These days, the Haroldsons seem to live pretty much month to month, as about half of American workers do. They likely have little to tide them over in hard times, in savings or investments. Most assets, 83 percent globally, are held by the wealthiest 10 percent.3 This family isn’t in that category. Like the vast majority of American households, they’re in the bottom 90 percent of wealth holders—those with thin or no asset holdings—among whom 73 percent own less than $10,000 in stock.4

Living largely hand to mouth—probably spending more on bank overdraft fees than on fresh fruits, as the typical American family does—they had no cash to hire a lawyer for the refinancings.5 When foreclosure faced the Haroldsons, a workable loan modification by a caring banker wasn’t in the cards—as it hadn’t been for millions of others. The Obama administration had encouraged banks to help borrowers stay in their homes, but few loan modifications had been done. Having the misfortune of getting Ocwen as their servicing agency, they dealt with a firm that had earned that F from the Better Business Bureau. Their phone calls might have reached someone in India with little knowledge of how to help the hamstrung couple and little incentive to do so.

THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN WEALTH AND CASH

Like many, the Haroldsons had walked into this situation because of the tantalizing cash on offer. What they didn’t grasp (or didn’t focus on) was the fact that they were liquidating an asset. They may not have known the difference between wealth and cash. Left untouched, their home would have created wealth over time as it rose in value. But because they’d turned that value into borrowed cash, they lost wealth. The cash had to be paid back, plus interest, plus closing costs, plus brokerage fees, plus prepayment penalties. Meanwhile, their slice of real ownership was depleted. Mounting debt remained.

Not being equipped to think about this chain of events, the Haroldsons focused instead on monthly payments. If they could afford the payment and get cash in hand, well, why not? To a family pinched by expenses, such a deal seemed a godsend. They didn’t fully comprehend that owning something—really owning it, free of debt—is the path to prosperity. It was this gap in economic literacy that the financial sector drove a Mack truck through. Along with millions of others, the Haroldsons went beneath the wheels.

At least they still had each other and had been spared divorce. Pretty much everything else was lost—the home they’d owned for 13 years, the equity that might have yielded them a little comfort, the neighbors and friends they’d enjoyed. They also lost their credit rating, and in the end, they declared bankruptcy. Their life on James Court had pretty much collapsed.

The larger social order around them was also experiencing collapse. The rising violence and fear I encountered in their former neighborhood was seen across Boston, as home break-ins between 2009 and 2010 soared 24 percent—and as much as 60 percent in Roxbury, a neighborhood bordering theirs. Boston Police superintendent-in-chief Daniel Linskey blamed soaring crime on the bad economy.6

Beyond Boston, collapse threatened the economy at large, with unemployment and underemployment plaguing a massive 17 percent of Americans in the early years after the meltdown, and with youth unemployment in some European nations higher still.7 One in four US children—one in eight Americans overall—relied on food stamps to stave off hunger.8 Across Europe, government and business leaders struggled to avert the collapse of the euro zone, as debt woes and economic crises struck Iceland, Greece, Ireland, Portugal, Italy, and other parts of the continent.

THE EROSION OF WAGES

Debt, in a way, was only a symptom of those multiple crises. A deeper issue was inequality. Had the Haroldsons’ son not lost his job, had Helen made more money, the family might not have needed to go so deeply into debt to stay afloat. Their plight wasn’t unique. Income for the majority of Americans had been flat for 30 years. According to Census Bureau figures, a male worker in 2007 earning the median male wage took home less, adjusted for inflation, than the typical male worker three decades earlier.9 In the roughly 20 years leading up to the recession in 2008, an astonishing 56 percent of the growth in income in the United States went to the richest 1 percent.10

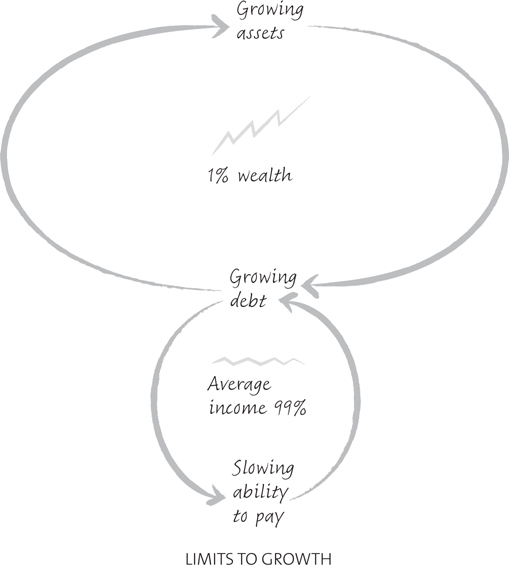

Had the share of income going to the middle class been larger, consumers wouldn’t have taken on so much debt to maintain their lifestyle. Had the wealthy gotten a smaller share, they wouldn’t have bid up asset prices so high.11 From a systems perspective, the problem is an economy that’s hitting the limits of its normal functioning.

Deregulation freed corporations to do what they’re designed to do, which is to maximize gains for shareholders. At a larger level, this means that the entire system becomes focused on increasing the assets of the wealthy. Yet many of those assets are the debts owed by the middle class. With middle-class incomes flattening, there’s less ability to pay off those debts. Thus the upward movement of wealth, from the real economy up into the financial economy, is constrained. Left to do what its basic design dictates, the extractive economy becomes overburdened with claims from above and undermined by the collapse of wages from below. The problem is that the system is designed to serve the few and not the many.

![]()

Yet in the downturn following the crisis, the system continued to follow its core logic: to increase profits for wealth holders and to decrease wages. When corporations found it difficult to increase sales, they nonetheless enjoyed record profitability. They accomplished this neat trick by cutting expenses, which in large part meant wages—also known as jobs. Companies used tactics like not rehiring, employing temporary rather than full-time workers, increasing workloads, and shifting jobs overseas. As a study by Northeastern University’s Center for Labor Market Studies showed, the result in one typical six-month period, a year or so after the meltdown, was that pretax corporate profits rose a massive $390 billion, while wages went up a tiny $70 billion.12

If this pattern seems particularly perverse at a time when working people are losing their homes and their jobs, it isn’t new. But there’s a curious piece to it. In the larger scheme of things, this pattern—maximizing profits for owners, minimizing wages for workers—has been at work since the days of the robber barons. Why had it suddenly become a problem in the larger system functioning? Why had the collapse of a few families like the Haroldsons triggered such a massive system response?

THE THRESHOLD EFFECT

The answer has to do with thresholds. Thresholds are the reasons why a system might suddenly jump into a kind of behavior not seen before. As systems theorist Ervin Laszlo noted, processes often don’t work in unbroken, linear ways. Things build up until a critical threshold is reached, and then sudden change is triggered. Think avalanche or mudslide.

When management of a system is intent on a single variable, success can create exponential growth followed by collapse. That’s the threshold effect: a point when a system flips from one state into another state, which is often degraded. There’s a disturbance, yet the system’s response is out of proportion to the size of that disturbance. In natural systems like forests or farming, one process that triggers a threshold effect is the human striving for maximum sustained yield. As ecologist C. S. Holling wrote, “Placing a system in a straitjacket of constancy can cause fragility to evolve.” Managing for a steady increase of one variable can cause instabilities to silently build elsewhere. Intensive management of forests can yield increased wood production, but create monocultures more vulnerable to injury from industrial air pollution. Bovine growth hormone given to cows can increase milk production, but make cows less healthy and shorten their lives.13

Keeping a system from flipping into a degraded state means respecting limits. It involves recognizing a simple systems insight:

Systems behave differently when at or near limits.

Economist Herman Daly put it this way: “As in physics, so in economics: the classical theories do not work well in regions close to limits.”14 Because of the excesses of financialization, the economic system was at or near limits, with financial claims four times GDP while millions of families were getting by on food stamps. These were logical outcomes for the design of extractive ownership. The constancy of seeking maximum profits for a financial elite caused instabilities to build, making the whole system vulnerable to collapse.

If the ecological concept of thresholds seems compelling, is it simply an analogy or something more? Is it accurate to apply systems thinking to the mathematical world of finance?

This is a question I pose one day to my Tellus colleague Rich Rosen, a physicist who also closely studies economics. There’s no doubt that the 2008 crisis was a case of overshoot and collapse, he tells me. But he adds that it’s hard to say there was a single, clearly defined threshold that was passed. With the financial system, he says, “there isn’t as clear a set of limits as you can define with physical systems.” (Even with physical systems, it’s often hard to tell precisely where limits are, he adds.) Debt grew dramatically in a few short years in the United States, but why did it collapse at one point and not another? The answer was probably tied up with inequality of income distribution, Rich says. At different levels of income inequality, different levels of debt would be sustainable.

“The constraint is the ability to pay back,” he says. “That functions as a kind of physical limit.”

The financial world operated with an implicit assumption that financial wealth could grow indefinitely, independent of GDP and independent of wage levels. And in theory, Rich says, he can imagine a scenario where that might happen: Wealthy people would bet against one another, and speculative activity would grow.

“But that’s not how it’s worked,” he continues. “In fact, in the real world, where the rich have gotten richer relative to the rest of the population, that means somehow they’re siphoning money from the rest of us.” With the wealth gap widening and the average person’s income not keeping pace, “the evidence seems to me pretty compelling,” he says. “This is not rich people betting against each other, but extracting from the rest of us.”

“Is that like one species eating all the ground cover so there’s less for other animals?” I ask.

“It’s more like a cancer cell, which has an ability to grow out of control where there isn’t enough of an immune system to keep it in check,” he says. “Cancer cells grow and kill the biological organism.” But there’s a limit to how far wealth extraction can go, he adds. Living systems out of balance find ways to right themselves. Something shifts. “At some point, people get rebellious,” he says. He adds what seems to me a good summary lesson of the whole mess.

“A fairer system is a more resilient system.”

Here is a kind of secular morality, a word for the social limits we’re hitting: fairness. An economy built on fairness, on designs aimed at a fairer distribution of wealth, is likely to be more resilient. If we are to avoid threshold effects (also called economic crises, which seem to be occurring every couple of years), it means managing not just for profits or growth but also for resilience. Resilience is the capacity of a system to bounce back from disturbances with its structures essentially intact. The opposite of resilient is brittle, prone to breakdown.

The economic system’s instability is related to its moral code. In an interdependent global system, overloaded with financial claims, the absence of fairness becomes dangerous. Limits of decency and fair dealing turn out to be real limits. Ethical limits and limits of system resilience are showing themselves to be the same thing. An unfair system will ultimately snap beneath its own weight. And it did.

![]()

The collapse of the Haroldson family’s finances is a part of what triggered the threshold effect of economic crisis. I’d finally been able to sort out the ownership tangle around their home—tracing how the twig of ownership they signed over had passed from mortgage lender to mortgage lender, was sliced and diced by Aegis, and was placed in a structured investment vehicle, pieces of which had been sold to investors. When the Haroldsons’ mortgage had gone bad, one splinter of the twig of ownership had passed to MERS, which began the foreclosure, and another splinter had gone to Ocwen, which earned fees overseeing the house as it stood empty. I’d seen how this disaggregated ownership system had fed a growing force of financial extraction and how that force had been building—hurtling toward a limit that the financial world could not conceive existed.

The resulting crisis is still sorting itself out. If housing prices in the United States have experienced collapse, much of the phantom wealth on the other side of the equation is still on the books. People are still pretending that those assets are real, trying to get those claims paid.

The Haroldsons, I discover, are still on the receiving end of those demands. Near the end of my visit, Michael mentions casually that he’s still receiving bills from Ocwen telling the couple that they owe money—despite their bankruptcy. “Every month a statement comes,” Michael says calmly, although I am incredulous. He goes into the back room to retrieve one, and I see that it is dated years after they lost their home. The statement says the Haroldsons owe close to $200,000.

“Are they calling you?” I ask.

“No,” he says. “Just the statements. We pretty much ignore them.”

I say that I wish I could personally offer help, and that if I can find someone who might assist them, I’ll let them know. Reluctantly, I stand to go. Helen asks me a final question.

“Did you notice the big tree in the front yard of the house?” she says. “We planted that when it was a little branch. We used to go out in the winter and tie it up to a stake, brush off the snow. Now it’s a huge tree.” Her eyes shine with pride.

“That’s something you deserve to feel good about,” I say, as I shake hands to leave. “That tree will be there for a long time to come.”

![]()

There are many things I still don’t know about the Haroldsons’ situation—many legal and financial details that attorneys could wrangle over. But I can say one thing with reasonable confidence, which is that they weren’t treated fairly. That wasn’t the only reason they lost their home. But it seemed a key reason. It was a key reason why the larger economy came close to collapse. It’s said that the flapping of butterfly wings in São Paulo can lead to a hurricane in Miami. The same might be said of mortgage fees unfairly charged, or contracts won through deception, which can trigger a hurricane in global financial markets. At its limits, an unfair system is an unstable system.

Some will say this family made unwise choices and is bearing the consequences. That’s true. But had they made the unwise choice of buying bad meat from a careless slaughterhouse, we wouldn’t lay the blame on them. Our society doesn’t allow the sale of tainted meat. Yet tainted mortgages remain legal and were in fact encouraged by the design of extractive ownership.

![]()

Back home after my journey to the Haroldsons’ apartment, I visit the website of that financial, insurance, and real estate company whose sign stood in the yard of the family’s former home. Its site shows photos depicting refinished wood floors and new appliances, indicating that the renovation of 56 James Court has been inside as well as out. The home has been divided and is being sold as two units. One lists for $289,000, the other for $279,000. I do a quick calculation. The real estate agent who bought the neglected house, after it stood empty for years, paid $206,000. Following renovations of, oh, let’s say $100,000, the amount put into the house would total around $300,000. The listing price is now $568,000. That means that the new owners will be pocketing around a quarter million dollars: not a bad profit, going to (surprise) the FIRE sector.