TWELVE

STAKEHOLDER FINANCE

Capital as Friend

In our talk at the Constitution, Ken Temple said something about the John Lewis Partnership that I found later in my notes. “We believe labor should employ capital, rather than capital employ labor,” he said. I recognized that formulation. It was also found in the writings of David Ellerman, an economist formerly with the World Bank, who was an early participant in Corporation 20/20.

After I return from London, I send an e-mail to David and find that he’s soon coming to Boston. I ask him to meet me for lunch. We sit down together at Mr. Bartley’s Gourmet Burgers on Massachusetts Avenue near Harvard Square, where David orders the Ted Kennedy, “a plump, liberal amount of burger” with fries, while I settle for the chicken wrap. With his white hair and long beard, David might easily be cast in the role of wizard or guru. He’s an articulate proponent of employee ownership and a critic of the absentee ownership that characterizes most corporations today. As we sit and talk about the financial crisis and its aftermath, he begins explaining why he thinks the key culprit is absentee decision making.

“The first principle is self-governance,” he says. “Markets only work when you couple decision making with consequences. Bearing responsibility for one’s actions is the whole basis of our legal system.” When you commit a crime—even when you are hired to do it—you are legally responsible. You bear the consequences. But this timeless principle is violated in the design of absentee-owned, limited liability corporations, he says.

When a company uses absentee ownership and absentee decision making—with boards representing shareholders who never set foot in the place—that design allows costs and consequences to be put onto others. Future generations may bear the cost of bad stewardship of the environment, David says. Employees may bear the cost of increasing productivity demands, decoupled from rising wages. Capital, meanwhile, enjoys the gains from production processes in which it plays little or no part. Actions and consequences are decoupled. Indeed, the whole aim of extractive ownership is to accomplish that decoupling, allowing capital to extract as much as possible (maximize gains) while bearing none of the negative consequences (minimize risk).

“If you bear the costs and get the rewards of your activity, you have a responsible relationship to your work,” David says. “If someone else bears the costs, you have an irresponsible relationship.”

REMOTENESS VS. CONNECTION

Economist John Maynard Keynes made a similar observation. “Experience is accumulating,” he wrote, “that remoteness between ownership and operation is an evil in the relations among men, likely or certain in the long run to set up strains and enmities which will bring to naught the financial calculation.”1

Remoteness arises subtly, and for seemingly good reasons. When a company sells shares or a government issues bonds, investors trade their money for a document giving them title to a future flow of earnings. This is productive investment in the real economy. But when a secondary market arises in the financial economy, things change. Investors sell their pieces of paper to other investors, shuffling ownership. Over time, making money through this trading often becomes the goal. Today, well over 95 percent of what goes by the name investing is really secondary market activity. Investing comes to resemble gambling, subject to the fears and fantasies of the casino. “When the capital development of a country becomes a byproduct of the activities of a casino,” Keynes famously wrote, “the job is likely to be ill-done.”2

The holders of paper investments become more and more remote from real enterprises. As this happens across borders, it’s worse still. In times of stress, it becomes intolerable, Keynes said. “I am irresponsible toward what I own, and those who operate what I own are irresponsible toward me,” he wrote.3

![]()

Systems thinking has a name for this kind of arrangement. It’s called suboptimization: allowing a subsystem to benefit, to the detriment of the whole.

When the goals of a subsystem dominate and the larger system suffers, that’s suboptimization.4 It’s the systems term for the 1 percent problem. When the 1 percent wealthiest own an estimated 40 percent of the globe’s wealth, as a United Nations study found, the stage is set for this problem to become global in scope.5 When their wealth is largely financialized, sliding around liquidly in capital markets, and when those markets are organized for investor convenience and profit, the fate of the world essentially becomes captive to capital markets.

Financial assets, as we saw, originate as the liquefied value of the real world (houses, businesses, various flows of cash). Lots of folks hold dribs and drabs of that wealth. But the big guys are the 1 percent wealthiest. The value of the real world, to a large extent, is in their hands. But “hands,” these days, basically means algorithms on autopilot. How it all impacts real life—creating jobs, destroying jobs, renewing the environment, damaging the environment—isn’t in the algorithm.

Yet here’s the really odd part. This suboptimal arrangement doesn’t even make wealthy people truly happy. Tim Kasser, a psychologist who studies well-being, says that when people organize their lives around the pursuit of wealth, they actually undermine their well-being. People with strong materialistic values experience more anxiety and depression, greater alcohol and drug use, and problems with intimacy. Their increasing wealth not only fails to satisfy them but also distracts from the things that would satisfy. Kasser finds that our genuine needs are for security, efficacy, connectedness, autonomy, and authenticity. Yet the single-minded pursuit of wealth and status leads away from these. Instead of feeling empathy with others, people feel competitive. Instead of feeling free, they feel pressured and anxious. The end result is lower vitality and life satisfaction.6

Happiness, on the other hand—as Christopher Alexander observes—comes in those moments when we feel most alive. A critical piece of that is being true to ourselves and in control of our own fate. In Kasser’s terms, it’s about authenticity and autonomy. In David Ellerman’s terms—and in terms of enterprise design—it’s about self-governance. In an interdependent world, there’s also the need for connectedness.

In generative design, connectedness and autonomy work together freely to create a whole that feels alive. Instead of 1 percent extracting most of the wealth, the 100 percent becomes fully alive. The quality without a name—that sense of wholeness and authenticity—tends to appear, Alexander says, “not when an isolated pattern lives, but when an entire system of patterns, interdependent at many levels, is all stable and alive.” A town becomes alive when every pattern in it is alive—“when it allows each person in it, and each plant and animal, and every stream and bridge, and wall and roof, and every human group and every road, to become alive in its own terms.” When that happens, he continues, “the whole town”—or enterprise, or world—“reaches that state that individual people sometimes reach at their best and happiest moments, when they are most free.”7

FROM MASTER TO FRIEND

The notions of suboptimization versus wholeness, 1 percent versus 100 percent, and connection versus remoteness are useful in approaching the issue of finance. They help bring the question of capital design into focus. To phrase the question in a human way, in terms of relationships:

How can capital become a friend to enterprise rather than a remote master?

One way to consider this, David Ellerman says, is through the question of who hires whom. In the dominant ownership design, capital hires labor. Capital is the corporation, the insider, and labor is the outsider hired to do work. In an employee-owned firm, that’s turned around. Employees are the insiders, and they hire capital. When employees bring capital into the firm, they bring it in as their friend, not their master.

This is the formulation that Ken Temple was referring to, when he said the John Lewis Partnership believes labor should employ capital. It’s an arrangement that’s real at JLP, where employee-owners bring in capital primarily through debt. A loan does not make the capital provider into an owner. Instead, that party is a supplier, conceptually outside the daily working of the enterprise, supplying something it needs. It’s no different from the way a department store might buy clothing or sporting goods from the suppliers making those items.

In recent times, JLP is making capital its friend via its John Lewis Partnership bond, available only to customers and staff members (not available through brokers). Over five years, the bond pays 4.5 percent annually, with an extra 2 percent in store vouchers. At the end of five years, the investment is returned in full.8 This is a paradigmatic design for Stakeholder Finance. It’s an approach to capital design that is personal and direct, in contrast to the anonymous and overcomplicated designs of Wall Street.

What JLP does not do is issue common stock, also called equity. This is the arrangement that creates that ownerlike relationship between investors and publicly traded companies. Equity investing means that an investor receives a variable return instead of the fixed return from debt. Return on equity comes in two forms: dividends (a slice of profits paid out directly to investors) and capital gains (the rising price of the company itself, reflected in the rising price of its stock). Because equity investors do well only when the company does well, they are in a position like that of owners.

By declining to issue equity to investors, the John Lewis Partnership is essentially refusing to liquidate the value of the firm. The billions of dollars it is worth remain frozen. The company retains strictly a use value: its value as a place to work and to shop. Its financial value—that invisible life alongside its material existence—never appears. This is so not only because of the nonissuance of equity but also (and closely related) because the company has a policy that it will never be sold.

In 1999, Ken told me, there was public speculation in a newspaper article about how much the partnership might be worth if it were sold. “It was very harmful at the time,” he said, because it created talk among partners about how much financial wealth each would hypothetically be able to pocket. The estimate was about £100,000 apiece (US$156,000). “For someone working in a shop, that’s untold wealth,” he said. But a sale will never happen at JLP, because no partner has any individual shares in the company; a trust holds all the shares. And the trust arrangements prohibit the sale of any of its equity. “It’s a tight design so we can be invested for long-term outcomes,” Ken said.

This is the final element, then, that completes the ownership design of JLP: its capital design. Stakeholder Finance joins with Living Purpose, Rooted Membership, and Mission-Controlled Governance to create an enduring, successful generative design at large scale.

![]()

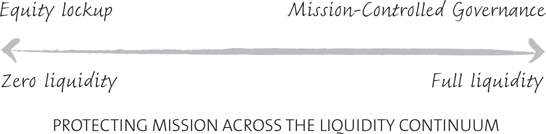

We might call the JLP approach to capital the equity lockup. The firm’s financial value is locked up in perpetuity, never to be liquidated and sold. There’s more than one way to accomplish an equity lockup. I’ve seen it take a slightly different form at the Massachusetts firm Equal Exchange, a fair trade coffee and chocolate company that is also employee owned. Its governing documents stipulate that if the firm is ever sold, net proceeds must be donated to charity. That’s another path to preventing the sale of a firm. Or, to turn this formulation around:

It’s a path to ensuring that an enterprise remains a living community—that it’s never reduced to simply a piece of property.

All companies potentially have that dual identity—as living system and as property. Because property is often a deadening concept, viewing a company as nothing more than dollars and cents in investor pockets, protecting mission generally means protecting a company’s living essence from the demands of capital.

But companies need not go to zero liquidity to accomplish this. We might think of mission designs for capital as lying along a continuum. At one end is zero liquidity, the equity lockup. At the other end is full liquidity, as when shares trade in public stock markets, yet mission is still protected. That’s the capital design at Novo Nordisk. At that publicly traded pharmaceutical, Mission-Controlled Governance keeps control of the board in mission-oriented hands, via super-voting shares held by the foundation.

Questions of full liquidity or zero liquidity are technical matters, details of ownership engineering. What’s really at issue is the deeper question of how to balance that dual identity of living system and property. While the John Lewis Partnership’s capital design ensures that the company is only a living system, many firms can’t go that far. Equity capital may be required.

In those situations, another way to make capital a friend is to create living relationships with local investors, socially responsible investors, or others with a stake in a company’s mission. This can be done with debt, as JLP does, or with equity.

THE OPPOSITE OF ABSENTEE

One of the best examples of stakeholder equity is found at Minwind, the wind development firm in southern Minnesota, which I decide it is time to visit. I set out one day for the drive there under a sky of robin’s-egg blue, taking Highway 169 south out of Minneapolis, with rows of corn fanning away on my right and left like tall fields of corduroy. My destination is Luverne, population 4,745, where I sit down with Minwind CEO Mark Willers.

Mark is a farmer, and the series of wind developments he’s helped to create are mostly on farmers’ land—sleek towers standing in cornfields and soybean fields that I drive out to see. When most farmers put wind turbines on their land, they lease wind rights to absentee developers. This might yield them a small fraction of the revenue, generally $4,000 to $12,000 a year. That’s the familiar path of rural poverty.

Minwind took another approach. Mark and other farmers decided they wanted to own the wind developments themselves. To raise the $4 million needed to put up the initial four turbines, they sold shares locally for $5,000 apiece. “And 66 investors snapped up all the shares in 12 days,” Mark tells me. These were among the first farmer-owned turbines in the nation. Minwind soon built more. Today there are some 350 owners in Minwind developments. The company created a requirement that no one can own more than 15 percent of any development. All shareholders must be Minnesota residents. And 85 percent of investors must be from rural communities.9

Now when one of these wind farms generates hundreds of thousands of dollars in revenue, all of it flows through local communities, to be used to pay wages, expenses, and returns to local investors. The wealth stays local, by design. Mark points to a GAO study that found when wind developments are locally owned, they generate three to five times the economic benefit of absentee-owned projects.10

In Minwind’s equity design, we see the opposite of the Absentee Membership and Governance by Markets used in extractive design. Here, those in control are not employees but farmers and local community members. Through the combination of Rooted Membership and Stakeholder Finance, Minwind’s design creates benefits both for communities and for the biosphere.

![]()

As we move into an era of ecological limits, “we face some tough choices ahead,” Mark says to me. “Really on a grand scale, we now have to limit things. We’ll have limited amounts of water. Do you want water to grow broccoli or to cool a coal plant? We’ve never had to make that choice before.

“When I look at an acre of land, I could put corn on it, wheat on it, solar panels on it, or wind turbines on it. I can grow soybeans for fuel,” he says. “The businessman tells me, ‘I don’t care about any of that; the only thing I want is a buck tomorrow.’ We’re talking about something far different.” Minwind is about keeping control of economic choices in the hands of those close to the land.

“What form of energy and what form of food do we want?” Mark says. “People need to ask, do they want broccoli, cows, solar, water—which is it you want? Then I’ll tell you how it’ll all turn out.”

Rerooting capital and ownership in human hands is far more than a technical issue. It’s about the kind of world we want to live in, and who gets to decide: the algorithms of the 1 percent or real people who care about the earth? But this isn’t about pointing fingers at anyone. The 1 percent are potential friends in the work of generative design. In fact, they’re often leaders. If places like Minwind and the John Lewis Partnership make capital a friend through generative design at the enterprise level, investors are playing a generative role on the other side of the equation, the capital side.

INVESTORS STANDING WITH THE EARTH

One of the most transformative movements of investors is Slow Money, the brainchild of Woody Tasch, a former venture capitalist who has helped launch a network of more than two dozen local investor groups across the United States (and one in Switzerland). Their aim is to “bring money back down to earth,” as Slow Money Principle 1 states. Intended as a companion to the Slow Food movement, Slow Money is about direct investments into the farmers and businesses that make healthy food possible, at relatively low rates of return. In St. Louis, a $6,000 loan was made to an urban farm. In Portland, Oregon, a Slow Money member loaned $40,000 for a new farm incubator on 80 acres of agricultural land. In North Carolina, baker Lynette Driver borrowed $2,000 to buy baking equipment.11

If this stuff sounds like small potatoes (one Slow Money group is called the No Small Potatoes Investment Club), it isn’t. It may represent the seeds of the future. Industrial finance is dying, according to Woody. “The deadly dull, making-a-killing-minded, buy-low/sell-high mentality of the 20th century fiduciary is dying. … Robber-baron invented Wealth Now/Philanthropy Later is dying. Something more integral is trying to be born, and we are among its midwives,” he wrote.12

What may be dying, in particular, is investing based on multiples of earnings. One of the rare people willing to stand up and talk about this is Leslie Christian, president of Portfolio 21 Investments—the person who devised the ownership model that inspired the B Corporation guys. Leslie used to be in the business of managing risk the old way, in her days long ago at the hedge management unit of Salomon Brothers. These days, she focuses on ecological risk. As we confront ecological limits, there’s a chance that we could face “an extended period of material economic contraction,” she wrote in a blog post. “To be blunt, this means no growth. This is the risk that no one talks about.” To ask Leslie more about this, I catch up with her by phone.

“We cannot assume growth as we have known it will go on forever,” she says. “It’s so obvious. And yet in the financial world, this hinges on heresy. When you talk about no growth or the end of growth to financial people, they laugh at you. They say you’re naïve, that you just don’t understand. They often default to human ingenuity, saying, we’ve gotten ourselves out of a lot of messes, we can do this.

“But the truth is, there will be limits to financial growth,” she continues. “I don’t know how it will manifest. It could be a social uprising. It could be another financial crisis and massive default, where governments hit limits on how much they can prop up lenders. New capital requirements are already slowing things down.

“There are a lot of points at which limits will be reached,” she says. “It’s going to crumble. That will result in lots of disruption. The crumbling will be very painful. That’s why we need to be designing all these models of alternatives. People need something to turn to.

“One possible change coming,” she says, “is a sudden or gradual shift in the P/E ratio—the multiple of company earnings that investors are willing to pay today because they expect earnings to continue and to grow in the future. Let’s say we’re now at an average P/E of 15. What if it goes to 10? That’s a 35 percent drop. If it goes down to a five-to-one ratio, that’s a two-thirds drop. Then the Dow would be down to 3,000 or 4,000 [compared with 12,000 to 13,000, which is where it stood in early 2012]. I cannot rule that out as a distinct possibility. But what’s the timing? It could be 50 years from now or one day from now.

“But still,” she continues, “I can’t dismiss public stock markets. I want to be invested in companies that will be here in the future, providing beneficial goods and services.” Her bet is on “selective growth”—growth in certain sectors that serve real human needs. And things could play out many different ways. “There may be a return to a situation where investors are seeking current dividends rather than future capital gains,” she says. “I think that would be really beneficial.”

![]()

As I begin trying to make sense of it all with my own tiny retirement portfolio, I sit down with my adviser, Donna Clifford, a member of the Progressive Asset Management network of socially responsible investment advisers. In a lovely bit of serendipity, we meet at the Equal Exchange Café next to North Station, as we talk about the possibility of my investing in Equal Exchange itself. The deal, it turns out, is the kind of thing Leslie talked about: no capital gains, only dividends. It feels similar to the kind of locavore deal that Mark Willers put together at Minwind, since Equal Exchange is local, about a half-hour from my house.

This worker-owned, fair trade coffee company is selling equity shares in the form of preferred stock—shares with lower voting rights than traditional common stock, paying an annual dividend of around 5 percent (not guaranteed, but historically the dividend averaged 5 percent over 20 years). The stock itself will not appreciate in value. I put in $10,000 and agree informally to a term of three years. After three years, if all goes well, I’ll get my $10,000 back. Plus the annual dividend.

I sign up. I write out a check to “Equal Exchange” and mail it to them. Imagine that. No impenetrable complex of intermediaries. About ten days later, I get an envelope in the mail from them. This trade is moving not at the speed of light but at the speed of life. My stock certificate is enclosed. Here I am, capital, being employed by labor. They in turn are working on behalf of small coffee growers in the developing world. “We are currently writing checks for coffee harvests in Colombia and Peru, so your dollars will be in the hands of small farmers in a matter of weeks,” the enclosed letter says. Dealing with these people fairly is the Living Purpose of this fair trade firm. Its policy is to pay steady, good prices for coffee beans—even if market prices tank.

Donna finds another similar deal, a wind bond being issued by about a dozen municipal lighting plants in Massachusetts, borrowing $65 million from state residents like me to fund wind towers. There are lots of other investments she and I agree are a good fit for me, like Portfolio 21 (Leslie’s fund), a Pax World bond fund, New Alternatives Fund, Parnassus Equity Income, plus other bond and mutual funds, all of it socially screened. Yes, I am investing in (gasp) the stock market.

Donna and I agree that we’ll try to shift 25 percent of my portfolio into impact investments, also called community investments—those direct investments that make a positive impact on the world, like the Equal Exchange and wind bond deals. Those deals can be hard to find. “They’re what more and more of my clients are asking for,” Donna says. “It’s part of the work that’s left to be done.” She adds that in two major recent crises—2001 to 2002 and 2008—“community investments were the only categories where some people made money.” Someday, I think, I might try to go 100 percent community investing. Couldn’t be much riskier than what the Dow’s been doing.

![]()

My journeys are nearly complete. I have a sense of what makes a company a living company and how various firms have solved the legacy problem. It has something to do with law but is really more about aliveness, about institutionalized patterns of fairness, about relationships where all parties can take care of themselves and work together for the good of the whole at the same time. Yet some of the best companies I’ve seen, like JLP and Minwind, are anomalies, single instances of designs that work but haven’t yet been replicated widely. This is the final piece I want to explore: networks, those living patterns that reach out beyond single companies to create whole systems of aliveness. It’s clear to me what the best example of that is. It’s the worldwide network of cooperatives.