ONE

DEBT, INC.

Extractive Design

As my friend Orion Kriegman and I climbed the pebbly cement staircase in the sidewalk that gave James Court a distinctive charm, he shared with me the story of his quest to buy the home we were on our way to see. It was a little two-unit at 56 James Court* in the Jamaica Plain neighborhood of Boston. After the family that lived there for 13 years lost it to the mortgage company, it stood empty for years. Orion had lined up bank financing to buy it. But when his real estate agent tried to make an offer, he couldn’t find anyone on the other end to talk with. No owner. Or at least no owner that anyone could locate. Some entity somewhere in the chain of financing had gone bankrupt, and the company left in charge was in absentia. Orion tracked down that firm through the register of deeds, but when he called the company—not once, but over and over—he felt he’d entered that special circle of Dante’s Inferno reserved for those on hold.

In his months-long effort to buy the home, he got as far as discovering that the “owner of record” was Ocwen Financial Services. But there the trail went cold. “Their phone service is a true nightmare,” Orion said. “There’s no category this fits in, so they transfer you to someplace where you can’t leave a message.” When he finally talked to someone, he figured he’d reached a call center in India, because the person spoke with an Indian accent and seemed to be working from a script with no provision for his particular problem.

“He gave me an 800 number, but I said an 800 number is not a direct line. ‘Oh yes, it is, sir, I promise it is, sir,’ he told me. So I tried it, and it took me back to the start.” Consulting again with his agent, Orion got the name of the person at Ocwen in charge of foreclosed properties and phoned him. At one point, he even found a returned message on his answering machine. But after calling the fellow back three times, Orion was met with a final, enduring silence.

Odd. How does one lose ownership? Where did it go? This intrigued me. Somehow, the seemingly simple fact of ownership had been deconstructed beyond recognition and vaporized. That process had triggered economic crisis across many nations—something like the splitting of the atom triggering nuclear explosion. Because the owners who’d lost this home seemed close to ground zero for the whole thing, I thought the story of this one family might help unravel how things had gone so wrong.

THROUGH THE WEEDS

Orion finished telling his story as we reached the house, where we stood for a moment. “I don’t even know if it has its plumbing anymore,” he said. A lot of abandoned homes didn’t. Scavengers had been known to strip out copper piping, rip sinks out of walls, and haul boilers out of basements. Since this home had plywood slabs covering its windows, we couldn’t tell what shape the interior was in. We pushed through the weeds to the backyard to try to see.

From beneath the side porch protruded the edge of a stained blue sleeping bag. “There’s definitely someone living under there; I see him all the time,” said a young man walking toward us (who didn’t seem to have bathed that morning). He told us that he too dreamed of occupying the house, as a squatter. Like Orion, he said he’d visited the website for the register of deeds to follow the tale of the home’s ownership. “It’s like seeing people’s life story in a handful of documents,” he said. Peering past this home’s boarded-up windows proved impossible that day. If I were ever able to see into the story of this home, I realized that I would have to be the third in our erstwhile trio to dig into the public documents posted by the register of deeds.

The tale began in 1992, when Helen Haroldson bought the 2,100-square-foot two-family house for $140,000, with a mortgage from Shawmut Mortgage Co. Five years later, she seemed to be getting a small business under way, because a Small Business Administration (SBA) loan was added in the amount of $23,500, secured by the value of the house. On SBA documents, the name of a husband, Michael, appeared for the first time—possibly indicating a recent marriage. With a home, a husband, and a business, Helen’s life seemed to be coming together. For two more years, all seemed to go smoothly. Then in 1999 the couple took out an innocuously small loan, $16,000, from a local credit union. In less than two years, they’d fallen behind on payments, and the credit union gave them a few months to become current.

The growing equity in the home allowed that problem to disappear. The Haroldsons got a $233,200 mortgage from Aegis Mortgage Co., totaling $50,000 more than all previous loans combined. That likely meant they’d added some cash for themselves into the refinancing (as well as cash for the hefty fees no doubt charged by Aegis). It was easy to imagine their relief. Yet had it been a Shakespearean play, this would have been the moment when the plot turned. Aegis (a company organized in the state of Oklahoma, with a post office box in Louisiana and a street address in Texas) would appear again in the Haroldsons’ life, as would a second corporation mentioned on this mortgage: MERS—Mortgage Electronic Registration Systems, Inc. MERS was a privately owned loan-tracking service created to facilitate the trading of mortgages. Its presence on the deed meant that this home’s mortgage could be sold countless times, with few hints of those transactions showing in county land records. MERS was, you might say, the legal representative of the financial whirlwind.

Nine months later, the Haroldsons were back with another new mortgage, this one from Ameriquest Mortgage. I recognized the name, because when the meltdown came, it made headlines as the object of multiple state prosecutions for predatory practices—such as pressuring borrowers to refinance when it wasn’t in their interest to do so. Perhaps in part because of lender fees and penalties, the mortgage was now $50,000 higher. It seems the Haroldsons had begun paying down old debt with new debt. From that point, it became painful to read on.

Six months later, another new mortgage—Aegis again. This one $71,000 higher. Another six months, another new mortgage, this one from a lender incongruously named Community First Bank, adding $44,000. Then an Instrument of Taking from the state Office of the Collector-Treasurer, threatening to seize the house for nonpayment of taxes. The notice arrived 12 days before Christmas. Five months later, the Haroldsons were back with another new mortgage—Aegis again (no longer organized in the state of Oklahoma, now reorganized in Delaware). This mortgage totaled a crushing $462,500. The Haroldsons hung on for another 18 months, and then MERS filed in court to foreclose.

Even in the dry prose of registered deeds, there was something raw about these transactions. The Haroldsons were clearly unsophisticated in the ways of finance, possibly lax, or, more charitably, desperate in their decision making. For whatever reason, they cycled through five mortgages in five years. Why did no bank counsel them? If reckless borrowing was clearly in evidence, the larger story—the enabling framework—had to do with reckless lending.

A TANGLED SKEIN OF OWNERSHIP

For years after the house was taken, the power of sale that MERS had claimed lay unexercised. Any ordinary bank would have wanted to see this home put on the market immediately. But this was no ordinary bank. MERS wasn’t the owner but a processing agency acting on behalf of some unnamed other. I guessed that Aegis wasn’t the owner, either, because companies like that often sold off mortgages within days. Aegis had also gone bankrupt, ceasing operations less than eight months after the Haroldsons’ foreclosure.

I thought the most likely “owners”—and the word clearly needs quotation marks in this context—were the investors in mortgage-backed securities. What such investors generally invested in were not individual mortgages, or even pools of mortgages, but instead characteristics of pools of mortgages, packaged into collateralized debt obligations (CDOs). Many of these investing vehicles melted down in the housing crash, making them possible candidates for the missing owner. Because of MERS’s presence, the whole thing remained opaque.

If the Haroldsons’ house stood at one end of this tangle of financial arrangements, at the other end stood investors. These often weren’t individuals but institutions—like the banks of Iceland, which were destroyed in the CDO meltdown, or the pension fund of King County, Seattle, which lost a bundle on structured investment vehicles. So it was that between, say, a Seattle policeman whose retirement depended on the performance of a mortgage loan and the mortgage payments made (or not made) by the Haroldsons, there stretched a complex of connections so densely woven as to be impossible to untangle when the need arose.

![]()

Holding the supposed responsibility for this snarled skein was Ocwen Financial Services. It was a story in itself. When I put its name into Google, I might as well have searched on the phrase “mortgage fraud,” so numerous were the lawsuits and allegations of abuse. According to a Government Accountability Office (GAO) report, the firm had charged the Veterans Administration for home repairs never made, instead leaving houses in disrepair and covered in debris. The Better Business Bureau of Central Florida, where Ocwen was located, had given the company its lowest ranking, F, after receiving 520 complaints in three years. In a customer service survey, J. D. Power and Associates ranked Ocwen dead last, in large part because of what the Palm Beach Post called “its tortuous and unhelpful phone services.” Orion’s suspicions about the call center in India were well founded. I came upon an announcement that Ocwen had hired 5,000 new people for its operation centers in Bangalore and Mumbai.1

Ocwen’s practices may not have been far from the industry standard. Abusive practices were in many ways the logical consequence of the incentives that financialized ownership creates. Mortgage servicers inhabited a cockeyed universe where fees increased as loans slipped toward trouble. The longer that loans remained in limbo, the greater the opportunity for junk fees. As mortgage servicers seized a property and prepared to resell it, they could funnel orders for title searches, appraisals, and legal filings to companies with which they were affiliated. Ocwen had established its own title company, Premium Title Services, in part to pocket more of that revenue. Because of these multiplying fees, mortgage servicers had little incentive to dispose of troubled properties quickly. They had little incentive to care what houses ultimately sold for, since the losses were not their own.2

Because Ocwen was a collection agency, interested in its own fees, it likely tended to see borrowers and their homes largely as production units: items in computerized databases with whom the firm had no enduring relationship. The players who had been part of a human relationship—those who arranged the loans—were gone. They’d sold the loans to financiers, who compiled the loans into products and sold them to investors.

If it was a mechanistic process, it was also a lucrative one. As a final note to the story of Ocwen, I pulled its stock performance chart. It looked like a fever chart climbing vertically. After a rocky period, the company found its footing in the post-crash environment and in a 52-week period saw its stock climb 140 percent. The reason was that Ocwen landed new contracts for managing troubled loans. Having likely played some role in the sub-prime mess as it unfolded, Ocwen was also making a bundle cleaning it up.3

When I thought back to the dilapidation of 56 James Court, the design logic that led there seemed clear. The breakdown in the physical architecture of the house traced directly (or rather, circuitously) to its ownership architecture. As ownership was deconstructed and repackaged, its atoms distributed hither and yon, the aim of the whole process wasn’t to help people stay in their homes. When families like the Haroldsons could no longer be tapped for escalating fees, they were shunted aside like debris, and houses were left to deteriorate. As a home loan shifted from one financial institution to another, a single aim was at work: to extract as much financial wealth as possible and to avoid responsibility if things went wrong. Financial extraction by companies and physical extraction by vandals went hand in hand. But they were not parallel processes. Finance was the master force.

THE RULES OF EXTRACTIVE DESIGN

The simple rules at the core of this story began to resolve themselves in my mind like a photograph coming into focus. To the brokers who created mortgages, the financial institutions that repackaged them, and the processors like Ocwen who serviced them, their shared motivations amounted to a unified system dynamic. The rules were so widely understood that they rarely needed to be articulated:

Maximize financial gains and minimize financial risks.

In their zeal to excel at this game, the players at certain points strayed across the line into fraud. Yet the problem wasn’t so much that people had broken the rules as that they’d followed them.

To understand the behavior of an entire system, it’s important to look beyond the players to the rules of the game.

That point was emphasized by systems theorist Donella Meadows, the Dartmouth College professor best known as the lead author of the 1972 book The Limits to Growth, one of the first to make the case that growth cannot continue infinitely on a finite planet. She helped develop systems thinking, which describes the common functioning of all systems, whether bacteria, organisms, ecosystems, or economies.

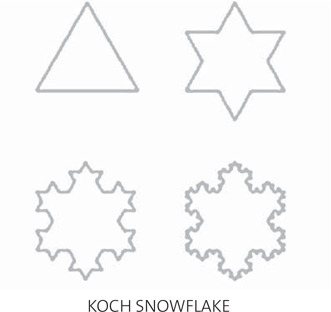

In her final book, Thinking in Systems: A Primer, Meadows observed that beneath the detail and complexity of the world, simple rules are generally at work. When those rules are repeated over and over, they spin themselves out in intricate ways, creating complex system structures. She gave the example of how a snowflake can be generated from a simple set of organizing principles. “Imagine a triangle with three equal sides,” she wrote. “Add to the middle of each side another equilateral triangle, one-third the size of the first one. Add to each of the new sides another triangle, one-third smaller. And so on. The result is called a Koch snowflake.”4

The way a single cell grows into a human being probably proceeds by some similar set of rules, Meadows said. “All of life, from viruses to redwood trees, from amoebas to elephants,” she wrote, “is based on the basic organizing rules encapsulated in the chemistry of RNA, DNA, and protein molecules.”5

Entire systems of organization can similarly grow from simple rules of self-organization—like the rules of maximizing financial gains and minimizing financial risks. These rules are based on deeper values, including individualism, the notion that the only relevant unit of concern is the individual self. What the rules say is to maximize gains for the self and avoid responsibility if others are harmed in the process. Harm to others is not something the system intends. It’s something the system ignores. What the rules say is, take care of yourself; forget everybody else.

These are the rules at the heart of extractive design. This is the design at work in the myriad forms of conventional mortgage finance and in the behavior of most publicly traded companies. When common rules are at the core of structures, the structures tend to produce characteristic behaviors. These structures can be called archetypes. Archetypes are the deep, simple patterns of organization that lie beneath the complexity of everyday life.6

The rules of maximizing gains and minimizing risk originate in the human heart. But they become a collective force, shaping the behavior of countless individuals working in concert, when they are embedded in institutional design. Organizations are more than random collections of individuals doing what they feel like doing on a given day. Behind the complex behavior of an institution like a bank—behind its loan offerings, its policies, the behavior of its employees—is a system structure that binds it all together, giving that system coherence and momentum.

Social systems are organized around a purpose in the same way that natural systems are organized around a function. The function of an acorn is to become an oak. The function of a river is to flow. The difference between function and purpose is the element of human choice. The purpose of an institution is selected by those with the ability to make that choice, the company’s owners. They express their purpose through the design of the organization.

Structure is purpose expressed through design.

This is the key lesson that systems thinking teaches us about the economic crisis: that the triggering events behind it were the result not simply of missteps by a few but of a larger system dynamic that encouraged those missteps. Financial Purpose was at the heart of it. The financial ruin of people like the Haroldsons wasn’t anyone’s aim. It was off the radar screen. Loans going bad didn’t bother brokers or financiers as long as their own financial interests weren’t at risk.

We’re closing in here on the serious design flaws encoded deep in the social architecture of extractive ownership. What its individualistic rules fail to encompass are the larger realities of system behavior—like the fact that everyone in a system can be acting in seemingly rational ways, yet their actions can add up to a terrible outcome. Or the reality that a system can, without warning, leap into behavior it’s never exhibited before.7 To create a system design built for those kinds of unexpected outcomes—which seem to be showing up with greater frequency in the 21st century—a different set of operating principles will be needed.