TWO

THE COMMUNITY BANK

Generative Design

If I found the story of 56 James Court a depressing tale, it also left me pondering a hidden anomaly: Community First Bank.1 In the five mortgages that the Haroldsons cycled through in five years, the bank that supposedly put “Community First” underwrote mortgage number four. It was a troublesome loan that lasted less than a year. It replaced a previous loan only six months old, and in the process it nearly doubled the family’s debt load. Shouldn’t a community bank have counseled the Haroldsons against signing their names to this loan? But instead, Community First Bank was the one inking the papers.

What was going on? In those boom years, had even community banks become little more than wolves in sheep’s clothing? If this bank’s name implied that it was a generative lender, why was it behaving like an extractive lender? Was my whole idea of generative ownership a crock? I decided I’d better dig in and find out.

Setting out to learn more about the ownership design of Community First Bank, I found the issue a slippery one. The first problem was its name. There was a Community First Bank in Butler, Missouri; another in New Iberia, Louisiana; still others in Harrison, Arkansas, and Kokomo, Indiana—to name a few. These were all separate legal entities, not branches of the same parent company. I finally tracked down the bank that the Haroldsons had done business with on the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) website. It was headquartered in Baltimore County, Maryland.

There were other problems. This bank was apparently small and locally owned (didn’t that mean it was one of the good guys?). And its legal structure didn’t tell me much. It wasn’t a publicly traded company, where ownership changed hands moment to moment. Instead, it was a privately held S Corporation—likely owned by a small handful of people, with key owners living in Baltimore or nearby. It also was a limited liability company (LLC). That meant its owners avoided liability for unpaid company debts or harms the company did. Yet for tax purposes, profits and losses flowed through to the owners. They got the gains and avoided the liabilities.

This legal structure was neutral. It was a shell inside of which lots of different things could be going on. I’d seen the LLC structure used by a southern Minnesota company called Minwind, which created wind farms designed on cooperative principles as a way to benefit farmers and keep wealth local. (I return to its story in chapter 12.) It was a great model, and because of the way tax incentives were written, it needed that tax pass-through. LLCs and S Corporation design patterns were practical, not sinister. To find the real purpose embedded in this bank’s ownership design, I needed to look elsewhere.

Next, I found that this bank had a federal charter rather than a state charter. And in the post-crash environment following the 2008 meltdown, it had been “aggressively seeking to open new retail mortgage branches across the country,” its website said. At that time, it had a dozen branches in a half-dozen states. I stumbled on a job listing for a franchise sales recruiter, who was to work full time on recruiting branch managers, each being promised “100% of the profits of the branch.”

There was more. Paradoxically, this was a small bank—at that time with only $70 million in assets—yet it was cranking out a head-spinning volume of loans: $1.3 billion in the five years up to 2008. Compared with other banks named Community First Bank (more than a dozen in all), it was processing nearly five times as many mortgage applications as the next largest.2 As far as I could tell, the others probably were banks aimed at serving their local communities. This bank was a mortgage machine. Because of its small asset size, it could not possibly be holding all the loans it created in its own portfolio. That meant it was selling them off, rapid-fire.

In sum, this was a bank standing on the head of a pin, churning out loans like so many widgets off a high-speed assembly line. And it was also selling mini-widget-making machines in the shape of bank franchises.3

This wasn’t a bank likely to focus on whether the Haroldsons could afford a mortgage over the long term. Its “primary business objective,” as its employee intranet site said, was “to originate mortgage loans through branch offices utilizing a web-based end-to-end paperless system.” And if a loan were to go bad in less than a year, as the Haroldsons’ had? Whoever bought that mortgage could seize the house and then sell it to extract the equity. Which is what happened with the Haroldsons’ final mortgage.

ANY GOOD NEWS OUT THERE?

So, OK. It was pretty likely that this bank wasn’t a generative lender. But I also hoped it was an anomaly. I began to wonder about other community banks. What about the banks that the Haroldsons didn’t encounter—the banks genuinely rooted in community? Did they behave differently? In the months following the 2008 financial crisis, I searched the torrent of e-mails surging through my computer, trying to sift out bits of hope from the flow of bad news. I found some interesting morsels.

The first bit I caught in my mental net was Self-Help Credit Union in North Carolina, long a leader among the nation’s 1,000 community development financial institutions (CDFIs).4 As a CDFI, Self-Help was a banking enterprise with a special charter from the US Department of the Treasury to serve low-income communities not adequately served by conventional banks. It did business with the same low-income borrowers that subprime lenders dealt with. But Self-Help’s mission was to serve these people, not to extract wealth from them. It meant taking care to place families in loans they could repay. The result—what a surprise—was that its loans, in those critical early months, held together as others were falling apart. As the Durham News reported in late 2008, “Prudent lender prevails amid crisis.”5

A lot of folks might have said Self-Help was a responsible bank because it was “small and local.” Yet it wasn’t particularly small. Over a decade and a half, it processed close to $6 billion in mortgage loans. Nor was it entirely local. Beyond its headquarters in North Carolina, it had branches in California and an office in Washington, DC, and ran a program aimed at aiding borrowers in 48 states.6

What distinguished Self-Help was its ownership architecture: it was a member-owned credit union launched by a nonprofit. That design was shaped by the Living Purpose at its core, the mission of helping people underserved by traditional markets. Among those it sought to help were low-wealth families, women, people of color, and rural residents. It aimed to use the power of finance to make the lives of ordinary people better.

That included serving people like Brenda and Silvio Granados, first-time homebuyers of an affordable home restored by Self-Help in Charlotte, North Carolina, where the credit union purchased two dozen abandoned homes, hoping to reinvigorate a community devastated by foreclosures. Self-Help also helped Darnella Warthen launch A New Beginning child care center in Durham, North Carolina, where some of the center’s kids had behavioral and mental challenges. Creating generative outcomes was at the core of why Self-Help existed. The fact that this organization had proved resilient in a crisis was welcome news. I soon found that it wasn’t a unique tale.

UNSUNG STORIES OF RESILIENCE IN CRISIS

I uncovered a similar story about Clearinghouse CDFI, a lender in Orange County, California—home of the bankrupt mortgage lender Ameriquest, from whom the Haroldsons had received mortgage number three. Clearinghouse CDFI had never done business with the Haroldsons. But it made loans to other risky folk: primarily first-time homebuyers, about half of them minorities. Among the loans that Clearinghouse had outstanding in late 2008, fewer than 1 percent had been foreclosed.7

That was fairly typical of many CDFIs at that time. A study by the Opportunity Finance Network (a CDFI trade group) showed that through first quarter 2010, CDFI loan funds experienced loan losses one-half those seen by banks overall.8 And this was despite the fact that CDFI loan funds dealt primarily with underprivileged borrowers.9

The story of resilience I was uncovering was very different from the narrative spun by business news anchor Neil Cavuto on Fox News. He said, “Loaning to minorities and risky folks is a disaster.”10 But that isn’t true, apparently, if financial institutions aim to serve risky folks rather than prey upon them.

As the recession wore on, this story darkened as CDFIs began to feel the impact of operating in low- and moderate-income areas where housing values were dropping and people were losing jobs in growing numbers. “Even though they were mostly not involved in the sourcing of ‘toxic waste’ sub-prime loans,” said the 2009 annual report of the National Community Investment Fund, CDFI banks were being hit hard by increases in delinquencies and loan-loss provisions.11 As Saurabh Nairan of NCIF explained to me, CDFI banks were suffering because they worked in vulnerable markets hard-hit by other unscrupulous lenders. “So, even though they have not originated bad loans, they suffer because folks in these markets are suffering,” he said.12

Looking beyond CDFIs, I dug into what was happening with the nation’s 8,000 consumer-owned credit unions. I found that at a time when megabanks were receiving billions in bailouts, the vast majority of credit unions needed none. These customer-owned banks remained conservative lenders, generally holding on to loans rather than selling them off. That gave them incentives to care whether loans would be repaid. On the other hand, a small number of their larger brethren—“wholesale” credit unions, providing services to smaller retail credit unions—experienced billions in losses. They’d abandoned their community-based footing and dabbled in more exotic mortgage-backed securities.13

Turning to still another category of community-oriented lenders—the nation’s 7,600 community banks—I found that most of these small, locally owned banks also seemed to be responsible lenders. A 2009 FDIC study found that in the post-crisis environment, banks with under $1 billion in assets remained the best capitalized, because their capital base hadn’t been eroded by excessive risk. According to the Independent Community Bankers of America, small banks were the only part of the industry to show growth in loans in the early post-crash period.

Community banks weren’t immune to failures, and there were some bailouts. But in general, they remained in good shape. By touting their strengths, some picked up market share. FirstBank of Colorado hired a single-engine plane to tow a sign over a Rockies game at Coors Field in Denver, reading, “This is the closest thing we have to a private jet.” In Fort Worth, Worthington National Bank ran billboards urging people to “Just Say No to Bailout Banks.” And in relatively short order, it found itself with $10 million in new deposits.14

![]()

The phenomenon I was tracking wasn’t limited to the United States. In that stunned period as the US subprime mortgage meltdown morphed into an international banking crisis, the state-owned banks of India were widely seen as havens of safety because their ownership framework kept them on the straight and narrow. The State Bank of India—60 percent owned by the government, with a mission of uplifting the people of India—in the three months after the crash saw its deposit base swell 40 percent.15 It wasn’t privately owned, but it did have a Living Purpose. In the Netherlands, Triodos Bank—whose mission was to make loans only to sustainable businesses—also saw its deposits grow substantially after the crisis.

The UK yielded an intriguing twist on this narrative. It was a tale told by the New Economics Foundation (NEF) in a white paper, The Ecology of Finance. This story had to do with a set of alternative financial institutions in the UK known as building societies, which are member-owned banking organizations. Their purpose is not to maximize profits for investors but to serve their customers, who are their owners. From 1986 on, building societies joined a stampede to convert to traditional bank ownership, a process known as demutualizing—leaving behind mutual ownership to become investor owned. The result, NEF reported, was that after the banking crisis, not a single one of these converted institutions was left standing as an independent bank. They’d all been absorbed into larger banks, or gotten into trouble and had to be rescued.

The most spectacular example was Northern Rock, a massive lender so wounded that it had to be nationalized and kept afloat by tens of billions of dollars of public money. “Just a year before its fall,” the NEF paper said, “the Rock testified to an all-party parliamentary group that ‘mutual status does not encourage efficiency. … [Our] success over eight years would not have been possible under the old mutual model.’” Yet in a crisis, the reverse proved true. The supposed efficiencies of the profit-maximizing model led Northern Rock to dash itself to pieces on the rocks of the financial downturn.16

SURFACING THE SUBMERGED

As I cast my net wider and wider, I found an increasingly coherent narrative of generative design. This story had been unfolding parallel to the tale of the Haroldsons and 56 James Court, but with a very different ending. It was the narrative of mortgage loans made to families by banks for whom lending remained a life-serving process: community banks, credit unions, CDFIs, and other lenders rooted in community. The loans of these institutions had, at a critical moment, been going bad in dramatically smaller numbers. Yet this was a story that wasn’t widely understood.

The most remarkable tale of its invisibility was told by Jean-Louis Bancel, president of the International Co-operative Banking Association, an association of cooperative banks, which are member-owned financial institutions, found all over the globe, that are run democratically in the interests of their customers. In the crisis, Bancel said, the cooperative banking sector “showed its benefits as a factor of stability and financial security for millions of people.”17 In remarks made in 2010 to the Organization for Economic Development and Cooperation, he told of the surprising size of the cooperative banking sector, which in Europe holds 21 percent of all deposits. In the Netherlands, the enormous Rabobank holds 43 percent of all the country’s deposits. Yet cooperative banks remain the “submerged part of the banking world,” Bancel said.18

They meet with a “relative silence on the part of academics and regulators,” he said. And he noted “a relatively widespread lack of knowledge” about this sector, even at institutions like the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF). In statistics kept by the IMF, he found no headings dedicated to cooperative banks. And as international regulators began crafting responses to the crisis, he continued, they proposed new capital requirements that would harm this sector. “Many cooperative banks may be compelled to abandon their cooperative status,” he said, “at an abnormally high cost,” to meet the proposed new requirements.19

![]()

Building societies, community banks, credit unions, CDFIs, state-owned banks, and cooperative banks each tell a story of success in crisis. Collectively, it is a tale of how generative design creates stability by avoiding excess.

The common outcomes generated by these models indicate that there are common rules at their core.

A genuinely different archetype is at work. At a moment when the extractive archetype was generating chaos, this archetype was generating community well-being. Homeowners were staying in their homes. Investors were finding stable income. Neighborhoods were avoiding the devastation of foreclosure. These community-oriented models had been generating these beneficial outcomes for a long time. Yet it was at the moment of breakdown that the contrast became starkly visible.

A NEW ARCHETYPE TAKES SHAPE

This is generative design at work. Instead of being about ignoring harm to others, it is about being of service to others. Instead of being about maximizing financial gains, it is about being financially self-sustaining over the long term. It is a phenomenon that defies the old categories of for-profit versus nonprofit organizations. Yes, some of these institutions do occasionally receive grants. Some have tax advantages that traditional banks don’t have. But for the most part, these are self-sustaining financial institutions.

They are profit making but not profit maximizing.

This is an ownership model that isn’t about extracting as much wealth as possible and then dispensing a few drops with a benevolent hand. Instead, these designs prevent wealth from concentrating in a few hands in the first place. They keep economic activity rooted in its original purpose of meeting human needs. Living Purpose is at the core of this archetype, in the sense of helping people to buy homes, start businesses, run day-care centers. This archetype is about generating the conditions for life to flourish.

This is the “true economics” that economist Herman Daly and theologian John Cobb Jr. describe in their book, For the Common Good. It is an economics that “concerns itself with the long-term welfare of the whole community.” It doesn’t center on homo economicus, that lone individual out to maximize his or her own income. Instead, what’s at work is a new kind of economic person, which they term person in community. It is about seeing one’s own well-being as integrally related to the well-being of others.20

If person-in-community is a new conception of the economic individual, generative ownership design is its logical counterpart: a new conception of the economic organization. It embodies a new set of rules. Instead of maximize financial gains and minimize financial risk, the new formula goes something like this:

Serve the community as a way to feed the self.

Come to think of it, this isn’t new at all. It’s what economies have been about since time immemorial. It’s what the butcher, the baker, and the candlestick maker have always done—serve the community as a way to make a living. The profit-maximizing corporation is the real detour, and a recent one at that, historically.

If the large, publicly traded, profit-maximizing corporation today is the single dominant model, generative design involves a variety of models. Member-owned credit unions are different from federally chartered CDFIs, which are different from the state-owned banks of India or the privately owned community banks in the United States. What makes them a single genotype are the common outcomes they generate and the common purposes at their core.

The different behaviors I saw at these institutions seemed unlikely to be the result solely of good people clustering at one set of organizations and bad people clustering at another set of organizations. There may have been a good deal of that. But somehow, one set of institutions made bad behavior more likely, while another set of institutions made good behavior more likely. How?

THE BANKER DOWN THE STREET

To trace the answer, I decide to look into the community bank where I’ve done my own banking for years, Beverly Cooperative Bank. It’s truly rooted in one community, for I could reach all four of its branches in a single afternoon on my bike. At the branch a few blocks from my home—the two-story brick building on New Derby Street in Salem, Massachusetts—I ask CEO Bill Howard to meet with me one day.

With his gray suit and square jaw, Bill is central casting’s ideal of the no-nonsense banker. Yet there’s an unmistakable kindliness beneath his reserve. He’s been at the bank more than a dozen years, he tells me, and in that time has seen fewer than ten foreclosures. “We’ve had no foreclosures this year and none the last year, and we have 1,000 loans,” he says. “If you look at other community banks, you’ll see similar stuff. They understand the community and have good underwriting standards.”21

As a small bank with $300 million in assets, Beverly Cooperative Bank wasn’t spared in the downturn. Some of its borrowers lost their jobs, and the bank worked with them as they struggled to repay loans. “We may go interest-only on their mortgage for a period of time,” Bill says. If people needed to talk, they could find him with relative ease, he says, adding, “Good luck finding anyone at Bank of America or Citibank.”

For 120 years, this bank has been chartered as a “mutual bank.”22 Unique to New England and the Midwest, mutual banks are classic hometown banks, the most famous of which is Jimmy Stewart’s fictional Bailey Building and Loan in the movie It’s a Wonderful Life. Mutual banks are state-chartered banks that have no outside investors and are run in the interests of depositors. Historically managed in conservative ways, these banks stayed on a relatively even keel through the Great Depression and the recent recession. But mutual banks are becoming a rarity. In the decade and a half leading up to the downturn, more than 300 abandoned depositor ownership to sell shares on public stock markets—in a process similar to UK building societies. I found that in the United States, fewer than 800 mutual banks remained.23

![]()

I ask Bill if he would consider going public. “My preference would be not to,” he tells me. “When you’re public, you have a different constituency,” he says, because stock analysts pressure publicly traded companies to grow their profits and create higher returns for stockholders. “The culture of a bank is different if it’s a mutual,” he continues. With no stockholders demanding higher returns, he doesn’t have to worry as much about short-term earnings. He can focus on his mission of serving the community.

If Beverly Cooperative Bank played little part in the mortgage meltdown, it’s nonetheless struggling in the aftermath—in part because the FDIC is levying higher assessments to cover the missteps of other banks. A few years earlier, the bank paid the FDIC fees of $26,000. Howard says he expects the fees to soon hit $600,000. “That’s 30 percent of our bottom line,” he says. Also creating hardship is an increase in auditing, which adds to expenses. “We’re audited to death,” Bill says. “We have an internal auditor. We have an external auditor. We have a commercial lending auditor. We have an IT [information technology] auditor. The state and the FDIC audit us. It’s rare we don’t have an auditor in here, and it increases every year. How can small banks do all this and survive?”

While many other bank presidents led their institutions to demutualize, Bill avoided that path. Yet what drove him didn’t seem to be benevolence or self-sacrifice, but some deep-rooted sense of how his own well-being was tied up with that of his community. The bank’s ownership design encourages that sense. Yes, leadership is also critical. Yet the largest element in Beverly Cooperative’s behavior seems to be its own design. This is a self-organizing system, with its own innate idea of what constitutes appropriate behavior.

FEEDBACK LOOPS: THE GOVERNING STRUCTURE

The bank’s behavior has to do with what systems thinking calls structure. Its structure shapes its behavior in the same way, as Donella Meadows put it, that the structure of a Slinky shapes how it bounces down the stairs. Beverly Cooperative Bank is a system self-organized around its own purposes. Self-organization is what makes an enterprise a system rather than a random collection of people. Meadows emphasized this in her definition of a system: “A system is a set of things—people, cells, molecules, or whatever—interconnected in such a way that they produce their own pattern of behavior over time.”

This is more profound than it seems. In eight simple words, Meadows articulated a truth that it took me 20 years to see at Business Ethics:

System structure is the source of system behavior.

All the auditing requirements placed upon Beverly Cooperative Bank suggest a different assumption: that the source of system behavior is the external rules fencing it in. This small bank has an internal auditor, an external auditor, a commercial lending auditor, an IT auditor, a state auditor, and an FDIC auditor because the regulatory apparatus assumes—as an unspoken premise—that banks can be controlled only by external watchdogs. That is why regulators reacted to the banking crisis by adding rules, which threatened to crush the small community banks and cooperative banks that for the most part didn’t contribute to the crisis.

Often left unseen is the issue of design: the notion that systems do what they are designed to do. Beverly Cooperative Bank aims to serve its community, rather than prey upon it, because that purpose is designed into its structure. Just as cows eat grass because their stomachs are structured to digest grass, and earthworms burrow in the dirt because their bodies are designed for burrowing, Beverly Cooperative Bank makes good loans because it’s structured to serve its community.24

Community First Bank of Maryland behaved differently because it was structured differently. But its structure couldn’t be reduced to its legal form. Its legal status as an LLC and an S Corporation didn’t govern that system.

The real structure is found in the rules of the game by which the system operates.

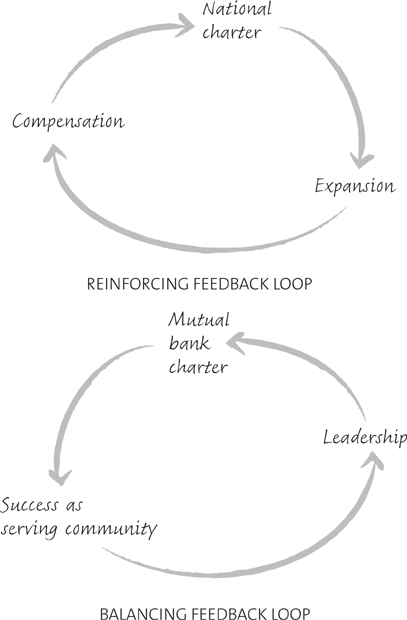

If the rules of the game originate with purpose, they become embodied in an organization through the feedback loops that govern behavior. In systems thinking, feedback is a loop where information is fed back into a system to direct its behavior. Reinforcing feedback loops amplify behavior. Stabilizing feedback loops moderate behavior. A system run only by reinforcing feedback will race out of control. Stabilizing feedback—like the thermostat on a furnace—maintains the equilibrium that living systems require.25

The design patterns that controlled Community First Bank’s behavior—plans for aggressive expansion, a national charter that facilitated this, and compensation that rewarded aggressiveness—came together to create a reinforcing feedback loop. Regardless of the bank’s name, and regardless of the fact that it was small and locally owned, this feedback loop governed its behavior.

Purpose and governance created the reinforcing feedback loop that made this bank behave like an extractive lender.

Beverly Cooperative Bank, on the other hand, had stabilizing influences that moderated its behavior. This wasn’t a bank focused on maximizing profits. It defined success as serving the community. It wasn’t led by someone out to maximize his own income, for if Bill Howard had been intent on that, he would have taken the bank public. Its mutual bank charter, its definition of success, and its humane leadership worked together to create a balancing feedback loop, making this bank a generative lender. This feedback loop was inseparably bound up with the bank’s purpose and governance.

Had lawmakers recognized the role of ownership design, they might have treated generative banks as part of the solution to the crisis. Regulators might have used bailout money not to prop up failing megabanks but to shift mortgage assets to community banks, CDFIs, and credit unions. In doing so, they might have enlisted the help of caring bankers in reworking troubled loans, possibly helping millions to stay in their homes (which Self-Help did, apparently with success).26 Along the way, our culture could have used the crisis as an opportunity to grow the generative economy.

If regulators didn’t take this path, citizens have begun to, with initiatives like the Move Your Money project, which encourages people to shift their assets to local lenders, helping them to find the most reliable ones.27 When the next financial crisis hits, perhaps we’ll make better use of the opportunity to shift assets from Wall Street to Main Street.

![]()

But thus far, the differing character of economic institutions is not something we as a culture think about very effectively. We don’t see that institutional character might be as simple as this: that generative lenders like Self-Help Credit Union and Beverly Cooperative Bank consider it their purpose to serve the community. And through local ties, balanced leadership, a definition of success focused on community service, and responsible compensation schemes, they remain tied to and accountable to a living place. Another group of institutions, including Aegis and Ocwen and that aggressively expanding Baltimore bank, considered it their purpose to maximize profits, which led them to focus much less on community impact. The abandoned 56 James Court stood as an emblem of where that extractive design led.

Still, the design of individual enterprise isn’t the whole story. These financial institutions are feeders into something larger than themselves. Bill Howard at Beverly Cooperative Bank hinted at what it was. There was little risk for mortgage lenders making abusive loans, he told me, “because the ink wasn’t dry before they were sold; if there had been no market for those loans, they wouldn’t have gotten done.” It was the purchasers of the loans—the megabanks located primarily in Manhattan’s financial district, the ones that sliced and diced and repackaged mortgage loans for further sale—who called the tune to which smaller lenders danced. To follow the thread of this story through, I needed to take a trip to Wall Street.