THREE

WALL STREET

Capital Markets on Autopilot

It was a trip I’d been meaning to take for a long time. For over two decades, my brother had worked on Wall Street, first at Salomon Brothers and later as a specialist on the floor of the New York Stock Exchange. There he’d been one of the auctioneers in the open outcry system through which, in the prehistoric days of the 1980s and 1990s, some 80 percent of stock trades had flowed. I’d intended many times to go watch Michael doing his job, and many times I’d put it off. Today Michael’s retired. The position of specialist has virtually dissolved. The Exchange visitors’ gallery is closed. When I asked him not long ago if he could arrange a tour of the Exchange for me, he called around and the message came back—in sum, no.

Well. I still wasn’t giving up. So one gray morning on a business trip to New York, I took the subway to the Broadway-Nassau stop and walked the four blocks south to the corner of Wall and Broad, pulling my laptop computer in a rolling bag behind me—planning to at least visit the Exchange from the outside. This was months before the Occupy Wall Street protests that later dominated the scene there. But even then, as I neared the Exchange, I could detect apprehension in the air, a sense of a place feeling itself under siege.

Street barricades for blocks around made the vicinity off-limits to all but pedestrian traffic. At the Exchange building itself, a more elaborate security apparatus came into view. The building’s main entrances—seven of them, each elegantly arched, with the regal mien of bank vault doors—were no longer in use. Instead, there was a single narrow passageway on the side, marked awkwardly by concrete barricades, where people were being shunted into the building under the gaze of security guards. Another clutch of guards scanned the sparse pedestrian traffic ambling by, as though the building were a soccer stadium where violence might break out, rather than the “financial crossroads of the world,” as street lamp banners proclaimed. A team of German shepherds stood leashed and ready.

Standing before the Exchange itself, I stopped and gazed at this Parthenon in lower Manhattan. Its neoclassical façade, marked by six Corinthian columns, gave it the presence of a Greco-Roman temple, a kind of hybrid between a house of worship and a house of government. It had the feeling of a public space—the market open to buyers and sellers that economic theory posited. And at one point, it actually had been a semipublic institution, because it was chartered as a not-for-profit. Yet as a small sign on the building told me, the Exchange was owned by Euronext.1 It had been sold to a publicly traded company. In a conundrum of the sort that artist M. C. Escher might have depicted, the exchange where stock traded had itself been turned into shares of stock that traded inside that exchange.

The air that the place exuded, there at the corner of Wall and Broad, was of an empire past its zenith. As I stood there wondering how I might render such thoughts on the page, I felt the gaze of a security guard on me and then on the laptop bag at my feet, which suddenly felt to me over-large and sinister. My visit to the Exchange, I realized, was at an end.

Thinking it best to saunter off, I strolled across the street to 23 Wall, the J. P. Morgan Building—“luxurious but unmarked, like a prestigious private club,” the plaque informed me. Down the road, I found the site where the City of New Amsterdam had in 1653 erected a plank wall—running from the Hudson River to the East River—to protect white inhabitants from Indian attack (the Indians perhaps angered after the “purchase” from them of Manhattan Island by the United West India Company). Eventually that wall had been torn down. But the dirt lane in front retained the name: Wall Street. It was along that lane that merchants and traders met to buy and sell the stocks of America’s emerging companies. When the current Exchange building opened there in 1903, it featured a sculpture I could still see, gracing the triangular pediment atop the six Corinthian columns. Its central figure is a caped female presence, standing with arms outstretched over other toiling figures. She wears the winged hat of Mercury, god of commerce.2

THE INVISIBLE LIFE OF CAPITAL

From this street emanates a magnetic force that is central to the system logic I am tracing. Things happen here that completely transform the nature of ownership. That change begins with capital formation.

The process of capital formation has been most charmingly described in an odd little book, The Mystery of Capital, by Peruvian writer Hernando de Soto. When Helen Haroldson took out that first mortgage for $140,000, her home, in de Soto’s words, came to “lead an invisible, parallel life” alongside its material existence. It assumed a second identity as a financial asset. Through this alchemical transformation, the value of property was drawn out and transformed into capital. Money appeared seemingly out of thin air—though in reality, it was the liquefied value of a tangible asset, the house on James Court.

We’re all “surrounded by assets that invisibly harbor capital,” de Soto wrote. “But only the West has the conversion process required to transform the invisible to the visible.” In many nations, he found, the poor have houses built on land where ownership is unclear, or they operate businesses that are unincorporated, and this lack of clearly defined ownership prevents them from turning their assets into capital. “In the West, by contrast,” de Soto wrote, “every parcel of land, every building, every piece of equipment or store of inventories is represented in a property document.”3

It is ownership that makes wealth creation possible.

Ownership is the original system condition. The act of legal registration of property—an act that the Haroldsons and their lenders performed with the Suffolk County Register of Deeds—initiated the process allowing the house at 56 James Court to generate capital. This documentation meant that property could be used as collateral for credit. Through the lending of money, property is made liquid and releases capital. In the logic of ownership design, property ownership undergoes cell division: it comes to have both a real identity (“real estate”) and a financial identity (a mortgage).

In the development of civilization, the harnessing of this alchemical process enabled the emergence of the industrial age as surely as did the harnessing of fossil fuels. If ownership was the foundational social architecture beginning in the agricultural age—allowing for the first time the settled life of farming—it was only with the development of capital formation processes that the latent power of ownership was fully unleashed. As the railroad barons and kings of capital harnessed the coevolving powers of capital formation and fossil fuels, it was as though Prometheus discovered fire a second time. Capitalism was born. The modern age came into being.

Today we’re encountering the hidden dangers of limitlessly burning fossil fuels and are similarly witnessing the dangers in limitlessly creating capital. But if the first danger has found a simple label in the phrase global warming, the second danger has yet to be clearly recognized. For want of a better term, we can call it excess financial extraction. More commonly, it goes by the enticing name of wealth creation, a process that society sees as ideally limitless. Therein lies the problem.

![]()

Capital formation begins innocently enough, when the ownership rights attached to a house are divided. As every first-year law student learns, ownership is not a single concept but a bundle of rights. We can think of those rights as a bundle of twigs that can be separated, with different twigs given to different parties. Thus when a homeowner obtains a mortgage, one twig is given to the lender, and it passes to whomever subsequently purchases the loan. The real owner—inhabiting the “real” estate—becomes a contingent owner, liable to lose her estate if she fails to pay. A new partial owner, the bank, obtains a claim on the house. A homeowner like Helen Haroldson still holds the majority of twigs from the ownership bundle, including the right of use, the obligation to maintain the home, and the right to pocket the home’s increasing value.

Yet the lender also obtains a significant right. For the twig that the lender holds can become a wedge in the door of property ownership—a way for that lender to potentially one day enter and take over the home. As our culture describes this event, foreclosure, it happens when the borrower “defaults.” The word itself implies that it’s the borrower’s “fault.” But in recent years, the nature of this arrangement has changed. That twig in the door has been turned into a Trojan horse: a way for the lender to insinuate itself into the borrower’s financial affairs in the form of hidden closing costs, balloon payments, high interest charges, and prepayment penalties.

As time showed, it mattered whom the Haroldsons invited to share their home. When lenders are generative—like authentic community banks, credit unions, and CDFIs—home loans can enhance homeowners’ well-being. But when lenders are extractive, homeowners can end up with the twig they’ve handed over being wielded against them like a two-by-four.

The ownership design of the lender makes much of the difference. In a world where most of us can’t make much sense of the six-inch stack of documents we sign at a closing, we fall back on trust. We don’t expect those documents on that walnut desktop to contain hidden time bombs, set to go off at some future date and destroy our lives.

The purpose and structure of lenders has a lot to do with why some conduct lending as an act of war while others conduct it as a neighborly relationship. Yet who lenders are connected to also matters. The networks of trading and investing that surround lenders have an enabling effect. Generative enterprise is supported by Ethical Networks, the rating systems and legal charters and groups of ethical investors that serve as a collective force, holding in place social and ecological norms. Extractive enterprise, on the other hand, is wrapped up in Commodity Networks, willing to trade or invest in anything—even destructive loans like those made to the Haroldsons—as long as there’s profit to be made.

Trading in the Commodity Networks of finance is vital to how money is made on Wall Street. After the initial act of capital creation, after wealth is drawn out of a house like 56 James Court, other conjuring acts of wealth creation occur that are unimaginably ingenious. Here in Manhattan, over and over again, formulas have been devised that create wealth—in mystically growing quantities—out of thin air.

ACTS OF FINANCIAL ALCHEMY

If I or the protesters who later gathered here had managed to get past the guards and crash through one of the sealed entrances of the New York Stock Exchange, it wouldn’t have mattered much. There’s no one in this seat of government to sit down and negotiate with. No one’s in charge. The essential action of the place is mathematical. That’s why its magic remains impenetrable to most people. People working on the floor of the Exchange, like my brother once did, don’t run the place or even need to fully understand how it runs—in the same way that people don’t need to understand how their home heating system runs, yet still they manage to stay warm. The genius of it all is built into the architecture. It’s designed into the logic of the system.

It’s hard for us to grasp this. So in the wake of financial crises, the inevitable hunt for villains has gone on, and quite a few, not surprisingly, have been found. But the heart of the matter is more subtle—more ordinary and more mystical, both. The action of finance is mercurial: not theft but ingenious sleight of hand.

The god known in Roman mythology as Mercury is in Greek mythology known as Hermes. He is the god of commerce invoked in Homeric hymn as a shape-shifter, “blandly cunning … a cattle driver, a bringer of dreams, a watcher by night.”4 Hermes is the patron of boundaries and of the travelers who cross them—the god of exchange and commerce. Hermes is a deified trickster.5

He’s an apt symbol for the magnetic force that pulled the housing and financial systems out of their customary orbit and into the path of crisis. In the process of exchange, or trading—in the issuance and sale of mortgages, and in the issuance and sale of ownership shares in banks—alchemy happens.

Financial wealth not only is released from property. It grows.

In the mercurial process of trading, the liberated molecules of ownership are spun and spun again into a larger body of wealth.

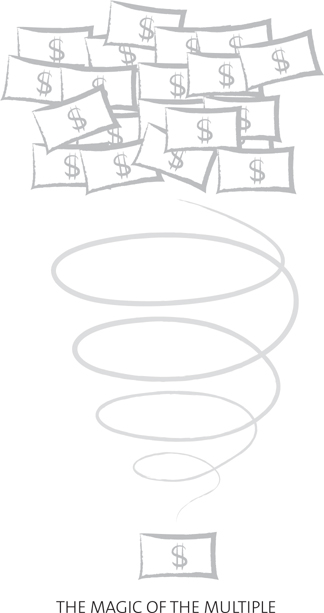

THE MAGIC OF THE MULTIPLE

At the heart of the design of the publicly traded company is a bit of alchemy called the magic of the multiple. It’s a capital formation process similar to the issuance of a mortgage. In the same way that value is drawn out of a house, it can also be drawn out of a company, like a bank. Its value is liquefied and released into the world through issuing equity.

The company comes to lead an invisible, parallel life alongside its material existence—assuming a second identity as a financial asset. This time, the asset is embodied in shares of stock sold to investors. This is the process that mutual banks in the United States and building societies in the UK went through when they demutualized and became publicly traded. They liberated the inert financial value of their institutions (along the way, allowing executives to pocket some of that liberated wealth for themselves).

Yet this wealth doesn’t just go into capital markets and circulate there, unchanged. It grows with the growth of profits, also called earnings. Here’s how.

![]()

For the sake of mathematical simplicity, let’s imagine JPMorgan Chase has $100 million in revenue and makes 20 percent profit. (Its revenues are in fact much higher, but its profits, in the years before the initial downturn, were pretty close to 20 percent.)6 How much will shareholders pay to own a machine that can churn out $20 million a year in earnings? That determines the value (market capitalization) of a place like JPMorgan Chase.

Let’s say that we as investors decide to pay ten times earnings, for a total of $200 million. This means that as owners of the machine, we can in ten years’ time earn back our entire investment. And our machine will then hypothetically go on churning out $20 million in profits every year. This company has a price-to-earnings ratio of ten (that is, the company’s stock price is equivalent to ten times its earnings—roughly what JPMorgan Chase’s P/E ratio was in 2007).7

But let’s say the machine is revving up. Everyone expects it to churn out $22 million in profits next year and $25 million the year after. Now what will investors pay? We might pay 15 times earnings. But let’s say lots of people are eager to buy this machine and there’s an auction. The price begins to climb. Now we might pay 20 times earnings. The P/E ratio rises to 20, which is where it stood for JPMorgan Chase in early 2010.

Let’s unpack what happened. At a P/E ratio of 10, this company is worth $200 million. But with the P/E ratio climbing to 20, the same earnings stream is suddenly worth not $200 million but $400 million. The perceived value of the company doubles. Money appears out of thin air. It’s due in part to auction psychology, and also to speculation. When speculators jump in en masse and chase shares, those shares can inflate beyond their underlying value. The trading process unleashes the magic of the multiple.

This is why publicly traded companies often have higher valuations than privately owned firms. The difference is something that economist Paul Samuelson tried to calculate in the bull market of the 1990s. He estimated that a company was worth about three times the value of its annual gross output if it was privately held and five times the value if it was publicly traded.8

Say you and I own a company with $5 million in gross output, or revenue. By Samuelson’s calculation, if we sell that company in a private sale, it’ll fetch three times output, or $15 million. But if we take that same company public, it’ll fetch five times output, or $25 million. The trading of ownership shares “creates” $10 million out of thin air.

Don’t worry if you don’t entirely get the math. It boils down to this: Taking a company public is like getting a license to mint money. Most of the time, people act as though this wealth is free, as though it just falls out of the sky. But it comes with a hidden cost. Watch how that cost is paid over time, and by whom.

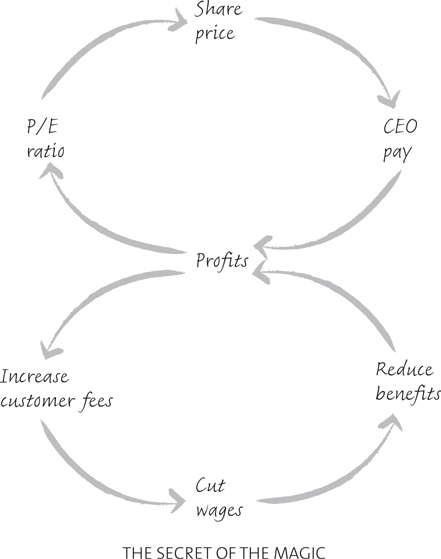

Imagine that Bill Howard changes his mind and decides to demutualize Beverly Cooperative Bank, turning it into a publicly traded company. He liberates the wealth locked up in that company and sets it trading in capital markets. Now he is no longer the president of a mutually owned bank, designed to serve its community; he’s the CEO of a bank with an ownership structure aimed at maximizing profits. Instead of being controlled by a stabilizing feedback loop, the bank’s behavior is now controlled by a reinforcing feedback loop. Profit is supposed to increase as fast as possible, forever. One design pattern keeping this loop turning is stock options. Whenever the bank’s stock price goes up, Bill is rewarded handsomely.

The community he is serving now is Wall Street, which exerts an enormous and continual pressure to keep earnings (profits) growing. Let’s say the bank’s stock has a P/E ratio of 20.9 That means that every dollar of profit the CEO can squeeze out is transformed into $20.

For every additional $100 of profit he can squeeze out of the bank, he will create—Eureka!—$2,000 in shareholder value. The alchemy of stock trading multiplies that $100 in earnings by 20. If this magic works wonders for investors, it can have a less benevolent impact on others—like employees, the community, and customers. If Bill can somehow extract $100 more in junk fees out of a borrower, he will create $2,000 in shareholder wealth. If he can charge $100 more in fees to checking account holders, shareholders will get another $2,000. If he can shave $100 off employee wages, shareholders again pocket $2,000. If he can reduce employee benefits by $100, another $2,000 shows up for shareholders.

If the magic of the multiple is indeed a form of modern alchemy, it also represents a kind of sleight of hand. Every dollar it can surreptitiously slip out of one pocket appears magically as $20 in the pocket of another. Consider that the revenues of publicly traded companies represent more than three-quarters of global GDP, and you begin to get a sense of the machinery behind wealth disparities.

Who should be benefiting from the wealth that companies create is rarely discussed in corporate boardrooms. The answer is assumed. As CEO of a publicly traded firm, Bill Howard will encounter general agreement—from his board, the financial markets, the business press, business schools, and the courts—that maximizing shareholder value is the noblest aim of his company. He is fulfilling his moral obligation, his fiduciary duty, to serve the company’s owners. Bill will thus have built-in incentives, and social permission, to take advantage of his borrowers, to work against the interests of his depositors, to pay his employees as little as possible, and to line his own pockets to the maximum extent.

It’s little surprise that in the grip of this system logic, a lender like Ameriquest was happy to give the Haroldsons a mortgage ill-suited to their needs. This was less a human transaction between two people than the mechanical workings of a globe-spanning system aimed at extracting as much financial wealth as possible. The system was doing what it was designed to do.

A THING APART

The tornado-force pressure of wealth creation has historically created a powerful pull in the world of finance. The stock market that began as a servant to industry—a tool to help fund new companies—ultimately subjugated business to its power, says Lawrence Mitchell, dean of Case Western Reserve School of Law, in The Speculation Economy: How Finance Triumphed Over Industry. Beneath the angelic countenance gracing the New York Stock Exchange, this temple came to house a fierce and exacting god of commerce. As the Industrial Revolution proceeded, Mitchell wrote, the stock market “quickly came to be the main thrust behind business, the power behind the boardroom,” driving the decisions of business and the path of the nation’s economic development.

The magnetic force of this place shifted the goals of industry from the manufacture of goods to the manufacture of stock.

Businesses were no longer created to serve the living community. They were created to manufacture financial wealth. Along the way, ownership shifted from the human hands of company founders into the anonymous hands of the marketplace, where people might “own” companies they’d never set eyes upon.

Ownership was no longer a tangible, enduring relationship with something real. It took on a machinelike quality, creating buckets of commodity earnings like widgets off an assembly line. The logic of it, in Mitchell’s language, turned the financial marketplace into “a thing apart, an institution without face or form whose insatiable desire for profit demanded satisfaction from even the most powerful corporations it created.” Its winged power to spin the capital extracted from business transactions into greater and greater wealth became an unstoppable force—a vortex of wealth creation too powerful to resist.10 Finance became the master force, Financial Purpose the purpose of the economy itself.

If the behavior of banks has to do initially with how hungry their owners are, Wall Street turned insatiable hunger into a permanent, impersonal condition. The stock market embodied a starkly new kind of ownership, reduced to a single laserlike focus: the quest to extract financial wealth in infinitely growing quantity.

As Bill Howard told me, “When you’re public, you have a different constituency,” a financial constituency. That changes the culture of a bank. If Beverly Cooperative Bank had gone public, he said, he could no longer have a mission of serving the community. His mission would be to create returns for stockholders.

Yet as powerful as the magical force of Wall Street is, it alone can’t fully account for the mess we’re in. Because it isn’t new. When my brother first worked at Salomon Brothers in the 1970s, the magic of the multiple was already an old story. Something—or some things—happened in recent decades to dramatically change the way financial firms behaved and the way borrowers like the Haroldsons behaved. New forms of alchemy were set loose. And one of those new forms of alchemy was speed.

SPEED TAKES OVER

From the subway stop where I get off, it’s a few short blocks to 84th and Madison, where I meet Michael at Le Pain Quotidien for breakfast one morning. As we take our seats in the back at a battered wooden table, I ask him to talk about the changes he saw in his three decades on Wall Street—to explain why and how things had become so much faster and more fierce.

The small specialists’ firm my brother joined, Adler Coleman, was a partnership. Salomon Brothers, Lehman Brothers, and Goldman Sachs were all partnerships in those days. Their primary focus was on long-term investments, Michael tells me. “A lot of things played together to create a more short-term focus,” he says.

A major element of the shift was a change in ownership design. These partnerships—Salomon, Lehman, Goldman Sachs—all became publicly traded firms. “That’s certainly one of the key reasons why we got into the mess we got into,” Michael says. “When I was there, we took a lot of risk, but because firms were partnerships, we were using our own money. If all of a sudden you’re using someone else’s money, they end up taking all the risk while you make all the money. That’s going to change your behavior dramatically. You’re going to get riskier and riskier.”

Another element of change was the removal of fixed fees on trades, which meant that trading became cheaper and volume increased. This went hand in hand with a shift in how stocks were valued. “When I started as a trader, we traded in fractions,” Michael explains, “one-eighth and one-quarter, three-eighths, a half.” A stock might be priced at ten and a quarter ($10.25) or ten and an eighth ($10.125). Over time, prices went to pennies. “You make a lot of money when you trade at one-eighth. You don’t make any when you trade at a penny,” he says. Since traders were pocketing less on each trade, they sought greater volume in order to make money. The pieces were falling into place for the volume and speed of trading to soar.

Michael felt the increased velocity in his job as auctioneer on the floor. His job was to match buyers and sellers of a particular stock, finding the price on which they agreed. As the speed of trading took off, “it got to the point where my mind was way ahead of my mouth,” Michael says. “As the order flow is coming in so rapidly—buy this, sell that—I’m giving directions to a clerk at a terminal. But by the time a price is coming out of my mouth, it’s too late, because another order has come in and the price has changed. When I got older,” he says (and “old” in the trading world meant 50-ish), “my mind wasn’t as fast. That’s when I knew it was time to leave.”

The pressure Michael felt was rising throughout the stock market, as the specialist system was giving way to computerized trading. In his early years at the Exchange, the number of shares trading in a given day might total 25 million. He left in 2002, and by the end of that decade, trading reached an unfathomable 6.2 billion shares in an average day. The open outcry system, the verbal, human exchange that Michael took part in, was morphing into the ethereal new form of electronic trading. Liquidity—the ability to move into and out of equity investments with ease—was becoming instantaneously at hand, as a perpetual sea of buy and sell orders moved about the globe at close to the speed of light.11

The phenomenon of high-frequency trading was taking shape, at speeds that made the blink of an eye seem slow. Velocity leaped far beyond the capability of any auctioneer’s human utterance, coming to be measured in thousandths of a second (milliseconds), even millionths of a second (microseconds).12 The metamorphosis occurred because traders developed ingenious new strategies for financial alchemy. One strategy was latency arbitrage, vacuuming up the tiny price differences that occurred in the infinitesimally small time lags between the sending of an order from one trading platform and its arrival at another. Another strategy might simply be called deception. Traders issued fake orders and canceled them a nanosecond later to get a sneak peek at prices that people would accept ($26.10? just kidding; $26.11? just kidding; $26.12? just kidding; $26.13? deal). In some trading models, deceptive bids, or canceled orders, represented up to 99 percent of all bids placed.13

High-frequency trading came to account for close to three-quarters of all stock trading in the United States. Firms employed robot computers to do daily battle—buying and selling securities tens of thousands of times per second—using algorithms, or computer codes, programmed sometimes just to trick other algorithms into doing trades, in the high-stakes gambling of Casino Finance.14

OWNERSHIP BECOMES ITS OPPOSITE

The whole thing is like an absurdist drama. Only it isn’t. This is virtually the entire infrastructure of the US economy: the so-called ownership shares in all public companies, which is to say, the liquefied value of the buildings and the products and the revenue flows of the vast majority of the economy. Mortgages on homes like 56 James Court are bound up in the madness, even if it’s hard to tell how. Mostly homes have become little bits of revenue streams—little bits of interest payments and closing costs and late fees and outsized prepayment penalties—which feed the swirling rivers of earnings that make the vortex spin. To keep it spinning, those rivers of earnings must grow every year. That means executives must generate more fees, more mortgages, faster trading. It’s a world—probably the only world—in which the Haroldsons’ five mortgages in five years make perfect sense.

Even at companies that don’t practice high-frequency trading, stock ownership has become more short term. One study of 800 institutional fund managers found that the typical holding period for stocks is a year and a half. For nearly one in five institutional fund managers, stocks are held an average of a year or less.15

![]()

The very concept of ownership, in its origins thousands of years ago, was about the end of nomadic wandering and the advent of a permanent relationship with the land. The human quest was about seeking, as Rainer Maria Rilke put it, “something pure, contained, narrow, human—our own small strip of orchard between river and rock.”16 That’s ownership. It’s about finding our place, settling down. As I’d seen it in my father’s life, and the lives of my grandfather and uncles, owning a company meant nursing it through good times and bad, being responsible for it and for the people who worked there. But in the world of Wall Street, “ownership” is the opposite of permanent. It’s the opposite of responsible. It has become a force that unsettles lives, helping to throw people like the Haroldsons and millions of others out of their homes.

That transformation happened when, in the division of ownership, in the breaking of property into its dual identities of real asset and financial asset, the financial side came to exert too great a force. The lure of wealth creation and the strength of the financial whirlwind became too great. The living balance was lost. What mattered now was Casino Finance, the world of “liquidity”—of placing bets, extracting wealth, and getting rid of ownership, over and over again, as fast as the human mind could imagine.

HEADING OUT

As Michael and I head out of the restaurant, an older man at a nearby table lays an arm on Michael’s sleeve. “I couldn’t help overhearing what you were saying,” he says, looking up into my brother’s face. He refers to a comment that Michael made about earlier days on Wall Street, when traders he worked with day in and day out had no tolerance for deception. “Your word was your bond,” Michael had told me. “If you were dishonest, it was very, very hard to make it up. You had to resolve issues immediately. It wasn’t like you could say, let’s go talk for a few minutes,” he’d said.

“I also worked on Wall Street for many years,” the gentleman says to Michael, “and you’re right, your word was your bond. That’s the way it was. But it’s not anymore.”

A new ethos had taken hold, and it made people like my brother and this gentleman recoil. Wall Street has always been about making money, but in recent years that aim became massively accelerated and over-the-top aggressive. The whole scheme of equity trading—the process of trading “ownership” shares—became programmed warfare. And that entire system was on autopilot. Moving at top speed. If it had become routine to trick and deceive other traders at the upper reaches of the system, who were invisible and needed never be dealt with again, how much less visible were ordinary people like the Haroldsons, whose mortgages were many steps removed? The tangible world of home ownership, the real world, was receding to the vanishing point.

The banks that the Haroldsons dealt with were not all publicly traded—yet when they sold off their mortgage loans, they sold them to financial firms that were publicly traded. In the end, the twig of ownership from the Haroldson house ended up as another spinning electron in public financial markets. As mortgages were churned out, they were sold to bigger financial firms that specialized not only in lending but in trading—trading mortgages, trading equities, trading derivatives, and so on.

Most of that trading in the United States—more than 90 percent—is generated by just six big, publicly held financial firms. Two are JPMorgan Chase and Morgan Stanley, the twin offspring of the House of Morgan, that exclusive club across the street from the Exchange. The others are Goldman Sachs, Wells Fargo, Bank of America, and Citigroup.17 The willingness of these big financial firms to buy and repackage loans served as a lubricant, an accelerant to aggressive mortgage lending throughout the nation. These were the titans of Wall Street that kept mortgage lending turning in its widening gyre.

The capital formation process that these giants set in motion was another form of financial alchemy. It involved speed, and that speed helped create a new phenomenon of size. The size of institutions “too big to fail” is part of it. But from a systems perspective, there’s something else at work that’s even bigger. We might call it, simply, overload.