FOUR

OVERLOAD

The Expanding House of Claims

Heading from New York back to Boston on the Acela train, I found myself turning over in my mind something Michael had said. It was about investment banking firms’ changing their ownership structures from partnerships to publicly traded companies. I’d been so engrossed in our conversation about speed, I’d glossed over that point. But I realized how critical it might be. Why hadn’t I heard others talking about this?

Back home, I dug around on the Web and found an academic paper exploring the changes in culture that occurred when Salomon Brothers went public in 1981, Lehman Brothers in 1984, and Goldman Sachs in 1999. Authors Richard Freedman and Jill Vohr of the Stern School of Business at New York University said this ownership shift had gone hand in hand with a dramatic change in the investment banking industry, from relationship banking to transactional banking—from customers’ having a long-term relationship with a single bank to an approach of searching around constantly for the best deal. They also said the shift in ownership structures accompanied disturbing trends at these firms: greater internal conflict, more greed (if that seemed possible), shorter tenure among employees, and an increasingly short-term focus.1 It was a telling portrait of what it meant to become a publicly traded firm.

Casting around further, I discovered that Michael Lewis wrote about this ownership shift in The Big Short—his look at who profited amid the 2008 meltdown. In his closing pages, he observed that “you could trace the biggest financial crisis in the history of the world back to a decision” made by John Gutfreund, when, “in 1981, he’d turned Salomon Brothers from a private partnership into Wall Street’s first public corporation.” Had it remained a partnership, Lewis wrote, the firm would not have leveraged itself so dangerously, taking on $35 of debt for every $1 of assets it held, as Salomon Brothers had. No partnership, Lewis wrote, “would have sought to game the rating agencies, or leapt into bed with loan sharks,” like the firms that did predatory mortgage lending. “The short-term expected gain would not have justified the long-term expected loss.”

When a partnership becomes publicly traded, somebody else takes all the risk, and you make all the money, my brother had said. Lewis said the same thing slightly differently. When Gutfreund took Salomon public, he and the other partners “not only made a quick killing, they transferred the ultimate financial risk from themselves to their shareholders,” he wrote. Risk taking accelerated. And when risky loans turned sour, more than a trillion dollars of the stuff was ultimately transferred to US taxpayers, Lewis continued, as the Federal Reserve stepped in to purchase bad subprime mortgages from banks.

Lewis concluded: “Combing through the rubble of the avalanche, the decision to turn the Wall Street partnership into a public corporation looked a lot like the first pebble kicked off the top of the hill.”2

What started the financial avalanche was a change in ownership design—a shift from partnership to publicly traded company.

Partnerships like Goldman Sachs and Lehman Brothers were not the only ones making that shift. When big banks gobbled up locally owned banks, when mutual banks converted to public ownership, and when the not-for-profit New York Stock Exchange was sold to Euronext, more and more of the financial sector flowed into that single ownership design: the publicly traded corporation. It’s an ownership design on autopilot, controlled by gamblers shooting chits around the globe thousands of times per second.

Its essence is insatiability. However much money these companies make one year, they need to make more the next. This design is also about institutionalized irresponsibility. The aim is to get somebody else to bear the risk. Thus the logic of the whole system led to a point where folks turned to creating toxic loans after all the reasonable loans had been made. Who cared, as long as the garbage could be thrown in someone else’s backyard? Then at some point, the whole world filled up with garbage.

The big banks kept the machine running—buying bad mortgages from predatory lenders with one hand, repackaging and selling them to investors with the other. What kept the big banks themselves in overdrive were the reinforcing feedback loops that governed their ownership design. It was all aimed at financial wealth creation. What could be better? And yet at some point, it tipped over into something else, for a reason that the system logic could not begin to encompass:

The house of financial wealth had grown too large.

After decade upon decade of siphoning more and more financial wealth, spinning it out into larger and larger bodies of assets, the global house of Wall Street had come to overshadow the Main Street base on which it stood. Yet in a system engineered to create that growing superstructure, it was impossible to see that its swollen size was now the problem.

PHANTOM ASSETS

To picture this state of affairs, it’s useful to think of two economies. As economic historian Fernand Braudel observed, “We tend to see the economy as a homogenous reality,” when in fact two economies existed as far back as the 15th century. The one most written about is the market economy, also called the real economy. It’s where people own houses and make and sell real things.

But there’s a “second shadowy zone, hovering about the sunlit world of the market economy,” Braudel wrote. This is the financial economy, where financiers manipulate exchange to their advantage—where “a few wealthy merchants in eighteenth-century Amsterdam or sixteenth-century Genoa could throw whole sectors of the European or world economy into confusion.” Instead of being about creating things that people need, the financial economy is about accumulating power, Braudel wrote. It’s where a tiny financial elite creates or benefits from anomalies, zones of disturbance, to amass vast wealth. The financial economy “represents the favoured domain of capitalism … the only real capitalism,” he concluded. “Without this zone, capitalism is unthinkable: this is where it takes up residence and prospers.”3

The financial economy is in essence a collection of assets: stocks, bonds, loans, mortgages, and the rest. These are all claims against the real economy. Every dollar of debt owed by one party is held by another party as an asset. The second party has a claim against the first. Thus the Haroldsons owed $462,500 on their final mortgage, and investors held those same dollars in their portfolios as assets. Those assets were claims against the Haroldsons’ income and against the value of 56 James Court, which could be seized and sold as a way to repay the debt. Similarly, assets in the stock market—shares of stock—are claims against the value of companies.

All forms of financial wealth are claims against something real. That real thing—the house, the company—is the true wealth.4

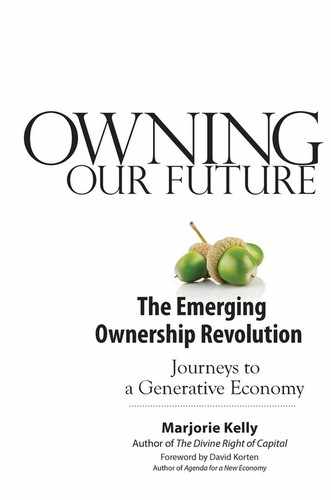

![]()

The financial economy can be pictured as a sphere dwelling above the real economy and drawing on its energy. In the early 1980s, these two worlds were in rough parity. The sum of global financial assets was roughly equal to global GDP. There was roughly a dollar of assets (claims) for every dollar of flows through the economy. But as the pursuit of wealth extracted more from the real economy—more mortgages, more fees, more profits, more bits of wealth that Wall Street wove like spun gold into substances of larger size—the sum of financial claims expanded massively. By the end of 2005, according to an International Monetary Fund analysis, financial claims reached nearly four times global GDP. There were roughly four dollars of claims for every dollar of GDP.5

The Haroldsons’ outsized $462,500 mortgage was one speck of sand in one brick in that overbuilt house of claims. But it told the tale. A couple that in 2002 held a $233,000 mortgage had within four years come to owe a debt nearly twice as large. As the couple spun out of one mortgage and into another, then another, then another, there was an artificial swelling of claims against the house. Because those claims were beyond anything the hamstrung couple could pay, they became unsupportable.

It was 2010 when 56 James Court was finally sold. I discovered this when I revisited the register of deeds site—about a year after my visit to the house with Orion—and found that a real estate agent had nabbed the house for just $206,000. Only with this new transaction was the identity of the long-invisible owner finally revealed. The dismemberment of ownership and subsequent legal messes had so clogged the system that it had taken years—as the house stood empty and weed-choked—before the details of the transactions had posted to the register of deeds.

But at last, there it was: the Haroldsons’ final mortgage had been held by Aegis Asset-Backed Securities Trust. It was a structured investment vehicle concocted by Aegis. There was no single owner of the single mortgage on this one house, just a nest of connections—a black box into which mortgages were placed, where they were blended and mixed, out of which issued little bits of claims on the stuff that investors could hold as assets. It was a microcosm of the shape of the whole system. Aegis, which had written the Haroldsons’ final mortgage (as well as two earlier mortgages), had apparently tried to emulate the big guys, doing its own slicing and dicing and reselling of mortgage derivatives. In the process, it went bankrupt.

The reason, no doubt, had to do with the fact that some of the trust’s mortgages turned out to be phantom assets. Half of the Haroldsons’ last mortgage was thin air. Investors thought they “owned” more than $200,000 in claims that in the end would never be paid. In the larger system, there were millions of similar cases.

Derivatives may have been the straw that brought the structure down. But the real problem was more vast.

The global superstructure of assets had come to exceed the load-bearing capacity of its foundation in the real economy.

The collapse of the mortgage on 56 James Court was one of the first signs of trouble with that overstressed foundation. But the whole edifice was set for a fall.

THE SILENT GROWTH OF “FINANCIALIZATION”

The mammoth swelling of claims against the real economy was the result of a process known as financialization. It is often defined as the shift in an economy’s center of gravity from production to finance. More broadly, author Kevin Phillips defined financialization as a process in which financial services take over “the dominant economic, cultural, and political role in a national economy.” It’s not clear who coined the term. But it’s a phenomenon that, as Phillips remarked before the meltdown, long remained underresearched and underanalyzed.6

In the United States, it was the turn of the millennium when, as Phillips put it, “[m]oving money around … surpassed making things as a share of the US gross domestic product.” Beginning in the 1980s, financial deregulation encouraged the finance, insurance, and real estate sectors—collectively, the FIRE sector—to interweave in so many holding companies that it became routine to see it as a single sector. By 2000, revenues of that sector reached 20 percent of GDP. Manufacturing slipped under 15 percent. That was a massive change from the postwar years, when making things represented close to 30 percent of GDP, while financial services was a relatively small 11 percent.7

In terms of profits, the shift was more dramatic. By 2004, Phillips observed, financial firms took in nearly 40 percent of all US profits—while manufacturers got just 5 percent. At the root of financialization was a single factor: debt.

The United States had shifted from manufacturing stuff to manufacturing debt.

This was how the financial economy had grown so large. The growth of debt occurred not only in the United States but globally, and it involved much more than home mortgages. As economist Nouriel Roubini wrote in Foreign Policy:

The credit excesses that created this disaster were global. There were many bubbles, and they extended beyond housing in many countries to commercial real estate mortgages and loans, to credit cards, auto loans, and student loans. There were bubbles for the securitized products that converted these loans and mortgages into complex, toxic, and destructive financial instruments. And there were still more bubbles for local government borrowing, leveraged buyouts, hedge funds, commercial and industrial loans, corporate bonds, commodities, and credit default swaps. … Taken together, these amounted to the biggest asset and credit bubble in human history.8

If debt expansion had been building for decades, its final swelling took place as the wealth engine of the stock market was stalling. In 2000, the dotcom bubble burst, leaving the NASDAQ composite index a decade later trading at less than half of its peak value.9 A not-dissimilar fate met the Dow Jones Industrial Average. From 1980, when the Dow stood at 1,000, it tripled within a decade, and tripled again in another decade—hitting the astonishing height of 10,000 at the century’s end. Yet there it slowed to a crawl. In the first decade of the new century, it would not surpass 11,000 for any extended period.10

There were reasons for that sense of siege at the New York Stock Exchange. Something was happening. Or rather, something had stopped happening. The wealth engine of the stock market was sputtering. As stocks bounced wildly in the years following the 2008 crisis, the price/earnings ratio—that magical brew that multiplied the value of earnings many times over—was losing its potency. In the first decade of the 2000s, the P/E ratio of the S&P 500 (an index of large companies) reached the extraordinary level of 30. By 2010, it had fallen to 15.11 The magic of the multiple was shrinking. The alchemy of Wall Street appeared to be approaching invisible limits. At least temporarily.

WHEN MORE MEANS LESS

If investors see these breaks in a once-steady upward climb as a misfortune—and hopefully a temporary one—systems thinking offers a different perspective. One of the signature insights of systems thinking is this:

There will always be limits to growth.

No living system grows rapidly forever. Yet this is how linear growth is conceptualized—as a straight line heading upward. As James Gleick wrote in Chaos: Making a New Science, “Linear relationships are easy to think about: the more the merrier.”12 The truth is, a system that attempts to grow in that way will hasten its arrival at its own limits.

A quantity growing exponentially toward a limit will reach that limit in an unexpectedly short time.

The Dow triples in a decade, triples again in another decade, and then boom—it hits some kind of ceiling. The NASDAQ soars and then crashes. In a linear mind-set, more can always be followed by more. But in nonlinear reality—the reality of living systems—more can sometimes lead to less. As Gleick wrote, “Nonlinearity means that the act of playing the game has a way of changing the rules.”13

In a linear relationship, Donella Meadows explained, you put 10 pounds of fertilizer on your field, and your yield goes up a couple of bushels. You put on 20 pounds; it goes up a couple more bushels. There’s a straight line of increase. But in nonlinear reality, “the relationships between cause and effect can only be drawn with curves or wiggles, not with a straight line,” Meadows wrote. If you put 200 pounds of fertilizer on your field, your yield won’t go up at all. Put on 300, she continued, and your yield will go down—because you’ve damaged the soil with too much of a good thing.14

But limits are an uncomfortable fit in the financial mind-set. Even after the bursting of the NASDAQ bubble, the exhaustion of the Dow, the explosion of the housing collapse, the near-meltdown of the global economy, and years of economic misery that followed, the giant California pension fund CalPERS was still projecting future annual earnings of 7.75 percent on its investments. In truth, over the previous decade, it had earned on average less than half of that, according to Richard Riordan, former mayor of Los Angeles. But financial models don’t draw the future in curves and wiggles. They draw straight lines.15

So it was that as the wealth engine of the stock market stalled, there were still buckets and buckets of financial wealth sloshing around the globe seeking places to earn that 8 percent, and the financial sector continued its search for new ways to absorb it all. Part of the answer was the swelling of debt. Banks sent credit card offers by the armload into homes. They urged families like the Haroldsons to turn rising home values into cash through refinancing and home equity loans. Companies piled debt on themselves with a record issuance of junk bonds. And governments built up debt as they ran deficits to pay for tax cuts, defense spending, and ultimately the massive bailout of financial institutions.

DEREGULATION AND DESIGN

On the consumer side, that torrential flow of money up into the financial sphere was unleashed in part by the abandonment of usury laws. Left behind was the ethical notion that there might be limits of decency and fair dealing to how much finance could extract from the pocketbooks of ordinary people. On the side of industry, the process was enabled by deregulation of many kinds. There was the dismantling in 1999 of the Glass-Steagall Act, which had separated banking from more speculative activities. Interstate banking restrictions had also been lifted, and massive bank mergers followed, leading to the demise of many community banks and the emergence of superbanks like Citibank and Bank of America. Beside them rose other towering presences, operating outside the reach of financial regulation: the investment banks, hedge funds, and private equity firms in the shadow banking sector, where much financing activity migrated.16

The whole process was aimed at transforming every conceivable molecule of economic value into a financial asset. It was Financial Purpose on a planetary scale. In truth, it was the transformation of real wealth into financial wealth—the shifting of assets from one side of the ownership equation to the other, from the real wealth of ordinary people to the financial assets of the elite.

This is what Occupy Wall Street would call the 1 percent problem. The relatively modest assets of the 99 percent, like the Haroldsons, were being transformed into debt, to be held as the assets possessed in large part by the 1 percent. After decades of this silent ownership shift, the top 1 percent wealthiest came to own more than half of the assets in the United States and 70 percent of all financial assets.17

Deregulation set the process loose. Yet beneath deregulation lay a deeper issue. What had been deregulated? Had it been the local knitting circle or the YWCA that was set loose, global economic crisis would not likely have been the result.

What had been deregulated was the essential architecture of extractive ownership—that institutionalized drive to maximize financial gains.

Extractive design didn’t create that drive. It began in the human heart. But extractive forms of ownership took financial wealth creation as a starting point, wrapped themselves around it, called it their purpose, measured progress toward it, rewarded it, and sought to remove all barriers that stood in its way. What began as a human impulse—one among many impulses—became an institutionalized, collective force of massive scale. The design of extractive ownership became, in essence, the design of the economy. It was a global engine driving toward a single goal. And deregulation removed the brakes.

The financial economy became swollen to four times gross domestic product (GDP) because all the energies of the system were focused on moving wealth up into the financial sphere. The aim was to liquidate and absorb the value of the real world, to keep the gyre of finance turning. Generatively designed financial institutions—community banks, CDFIs, credit unions—kept their energies rooted in the real economy. Their aim was to meet the needs of life, to build real wealth. But one form of ownership was devouring the other.

As financial ownership became swollen, real ownership was transformed into a kind of debt peonage, where a couple like the Haroldsons might pay and pay and pay, and in the end own nothing. Between 2000 and 2004, home values soared by 40 percent, but homeowners ended up with a lower percentage of equity ownership in their own homes.18 The gains in home values went to creditors. What happened to the Haroldsons happened not only to countless others, but also to the GDP of the global economy. Yet the aim of extractive ownership remained the same: to create still more financial assets.

There was also that other part of the operating system: minimize risk. This was the next force I needed to trace to complete this design journey. If extractive ownership had a natural tendency to kick the system into overdrive, there was another tool of ownership that made folks feel secure operating in that hyper-risky way: derivatives. The question began to formulate in my mind: how could I pay a visit to the abstract world of derivatives?

LOSING TOUCH WITH REALITY

I check my map to pinpoint where I am to meet my friend for lunch: the Boston Stock Exchange building, a 20-minute walk from the Tellus Institute, across the Boston Common to the Financial District. I’m on my way to see John Katovich, a longtime participant in the Corporation 20/20 project and one of the most creative thinkers I know, in both traditional and generative forms of finance. One of the founders of Katovich & Kassan Law Group in San Francisco and the former chief counsel for the Pacific Stock Exchange, John was for the moment chief regulatory officer at the Boston Stock Exchange.

He had moved to Boston because that exchange agreed to let him explore the creation of a local stock exchange and a socially responsible stock exchange, in return for John’s helping them with their regulatory needs. But within a few months of his arrival, the Boston Stock Exchange was sold to NASDAQ. Its operations were moved out of Boston. John found himself chief regulator of a piece that remained: the Boston Options Exchange, the hub where stock options were traded. As it turned out, he would move back to the Bay Area a few months after our meeting. But for a brief window of time, his presence in Boston offered me, serendipitously, a way to take a renegade insider’s tour of the world of derivatives in the form of their plain vanilla variation: the stock option.

Stock options are among the simplest forms of derivatives, which I thought might make them a reasonable stand-in for that larger family of financial vehicles derived from—a step (or two or three) removed from—securities like stocks and bonds. Visiting the exchange where stock options are traded seemed a way to find the ground beneath the esoteric financial instruments that played such a fateful role in the life of the Haroldsons. Entire libraries have been written about derivatives and their role in triggering the financial crisis. But what I’m after in this visit is something physical: I want to see what derivatives trading looks like to a person standing somewhere on the earth.

![]()

As the Boston Stock Exchange comes into view, I see that it isn’t nearly as grand as the New York Stock Exchange. It’s 12 stories of creamy white granite, with its own understated elegance—for example, in the lamps on either side of the entrance featuring sculpted figures in flowing robes of bronze. Pulling on that entrance door, I find it locked. Around the corner is another entrance that stands open; inside, men in hard hats and tool belts walk around. The former stock trading floor is being transformed into a bank. The foreman points me to a third entrance, where I enter a narrow marble foyer and take the elevator to the second floor. A small sign on the wall reads, “BOXR: Boston Options Exchange Regulation.”

John meets me, and we walk together to the market operations center—“the central control room,” he calls it. It’s a quiet room with beige carpet, where a few guys sit in swivel chairs. Occasionally they glance at multiple screens where numbers blink. This is the exchange where trades on 215,000 different stock options are cleared. Through these computers 10 million contracts a day flow. Among other things, John tells me, “We’re measuring the health of the system.” They are at that moment “measuring latencies”—the speed with which orders are executed. Latency is the time between when an order is typed in, somewhere in the world, and the instant it is posted to the system and executed. “In the old days it was one minute,” he says. “Now it’s 10 to 15 microseconds” (millionths of a second).

A stock option, John explains, is the right to buy or sell shares of a particular stock at a preset price during some month in the future. “Google has maybe 500 different options,” he says. If Google is trading at, say, $450 per share, someone can lay down maybe $5 (the price fluctuates constantly) for the right to buy 100 shares of Google at $460 a share in November. There are likely 499 other variations on this. Which makes sense, sort of.

“You can close your position without ever having owned or touched the actual stock,” John adds. Here my ears perk up. “In fact, most of the time you don’t touch the stock.” Options, in other words, are only tangentially related to reality—the “reality” being the momentary price of Google, or any other stock. When you buy an option on Google for which you pay $5, you don’t actually need to use that option to buy or sell Google stock. Instead, you might sell the option itself for $10 and pocket the profit. The option itself is the thing you own.

In effect, you’re trading little invented pieces of real estate in time. When that tiny piece of real estate opens its doors in November, you can hypothetically stand on it and buy those shares of Google. But in the vast majority of cases, you don’t. Options are their own universe of financial value, above and beyond the value of the underlying stock. They’re something else for traders to own and trade and make money on—like baseball cards, carrying a value entirely apart from the players (such as Google).

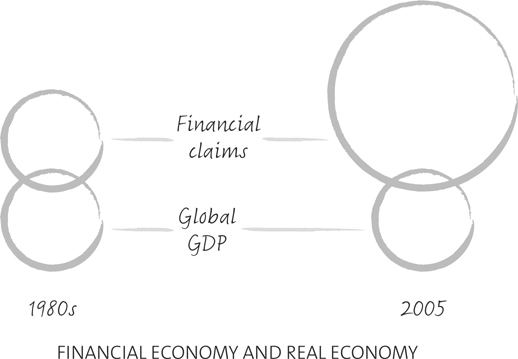

For all those financial assets swirling in the financial economy—all those bits of extractive ownership zooming around, searching for a place to land and extract their due—derivatives are a new landing pad. They’re a new architecture for extraction, allowing the business of “creating wealth” to stake ownership claims in a new realm. There is the foundational world of the real economy. On top of that stands the financial economy. And above the financial economy floats this more fictional and hence more vast and boundaryless new frontier: the world of derivatives.

THROUGH THE LOOKING GLASS

Stock options are a tiny sliver of this new sphere of value, which has become massively swollen in the era of financialization. The stock option is just one form of derivative, and there are hundreds of other forms, with more being invented all the time. As a whole, financial derivatives comprise a sphere of uncertain size and unimaginable complexity. Charles Morris summed it up nicely in The Trillion Dollar Meltdown. While basic financial assets—stocks, bonds, loans, mortgages—before the crisis grew to four times global GDP, on top of that house of claims, derivatives swelled to ten times global GDP.19

There were reasons why Aegis and Community First Bank were eager to make risky loans to people like the Haroldsons, who in anyone’s wildest dreams would never be able to pay them back. Chief among those reasons were two kinds of derivatives. The first was collateralized debt obligations (CDOs). When a mortgage firm issued a mortgage and sold it the next week to, say, Goldman Sachs, that firm sold it again to investors—but first it worked its alchemical magic, turning dross into gold. It placed a batch of mortgages in a blender, sliced and diced them, and then sold off various layers. Investors could buy the cream at the top, the dregs at the bottom, or the stuff in the middle. Investors weren’t buying particular mortgages; they were buying aspects of mortgages. This was part of what had obscured the ownership of the Haroldsons’ home. CDOs were one type of derivative implicated in the meltdown.

There was a second type. It was the reason why investors were blissfully content to buy the dregs at the bottom. It was a form of insurance called a credit default swap. It meant that if mortgages turned out to be worthless, the holder could collect on the loss. It was like owning a house and buying fire insurance.

Here’s where things get truly weird. It’s possible to buy credit default swaps even when you don’t own the entity holding the underlying assets. These are derivatives called naked credit default swaps. With these, in essence, you can buy insurance on a home you don’t own. Metaphorically, there can be one house with a hundred insurance policies against it. Then if the house burns down, a hundred people will have to be paid. The payout will be a hundred times the value of the house. Now, if this isn’t Alice in Wonderland, I don’t know what is. And it’s only one example of the shenanigans going on in the world of derivatives.20

A similar derivative is the synthetic CDO, which is an investment engineered to behave like a particular basket of mortgages, except—voilà!—there is no underlying basket of mortgages.

Now, consider for a moment. All financial assets are at one time born as claims against something real. A mortgage is a claim against a house. A share of stock is a claim against a company and its stream of profits. Simple derivatives, like the option to buy Google in November at $460, are one step removed from real assets. But then, quietly, at some unheralded moment, the thin thread connecting derivatives to reality was severed. Derivatives were engineered into existence—like naked credit default swaps and synthetic CDOs—that were claims against thin air.

In the long evolution of capital creation, these derivatives represented an unseen solstice, a moment when the lengthening days of wealth creation reached a zenith and began the turn toward something else, not the creation of wealth but its decay. They were so complicated that few knew any line had been crossed. Some derivative contracts can run to multiple pages in length. Yet as long as only a small number of houses were burning down—as long as mortgages weren’t yet going bad—investors were happy to buy this through-the-looking-glass stuff, thinking themselves sophisticated in doing so.

THE FLAW IN THE FORMULA

The problem with the system traces to the organizing principles of extractive ownership. Selling mortgages beyond the point where they make any sense is about maximizing financial gains. Nothing in that core rule says, maximize gains only when it makes sense in the larger system. Building concern for the common good into this stuff is considered naive.

The only risk that extractive design cares about is risk to the self.

That’s the flaw. For when the financial sphere is four times global GDP, the moves of finance are like the moves of an 800-pound gorilla deciding where to sit. Some small atom of “self” is no longer the appropriate unit of reference. At work is a global system of market governance: a system of governance and a system of worship, both. When that system is intent on maximizing the gains of the few and disregarding impact on the many, the results can be catastrophic. But extractive ownership design doesn’t concern itself with this.

It assumes that risk can be managed at the level of the individual firm or portfolio, using diversification of assets, or derivatives. If an enormous gain for Aegis means certain and massive loss for the Haroldsons, well, tough. What happens to little people is off the radar screen. Thus it was that hard-nosed businesspeople and sophisticated investors drove the world economy to the edge of a precipice, imagining all the while that they were doing what any prudent person would do. They were following the fiduciary duty to maximize gains for investors.

Derivatives in one sense are something new. But in another sense, they’re the old system of extractive ownership spinning itself out in evernewer forms—a Koch snowflake growing larger and larger.

A statement by Ron Chernow, author of The House of Morgan, a book about J.P. Morgan, put it all in perspective. “Wall Street for a number of years has been gripped by a quiet crisis,” he said, just days after Lehman Brothers collapsed in a fiery heap in September 2008. “Beneath all the financial wizardry, beneath all the financial engineering, there has been an increasingly desperate search for new sources of profit. [italics mine].”21 That’s the best simple description of derivatives ever uttered. If assets like stocks and bonds can’t spin off wealth fast enough to satisfy investor appetite, it’s because they have the pesky habit of remaining tethered to the real world. Ultimately, the best way to satisfy the need for more is to remove oneself from reality. That means engineering things derived from reality. In the end, it means losing touch with reality.

![]()

As John and I take our seats in his office, he shows me how all this looks to a trader. “If you pull up your Thomson Reuters screen, you get a snapshot of some things going on,” he says, turning his computer monitor so that I can see it. “This is a snapshot of the world market.” On the screen are rows and columns of numbers, many blinking and shifting. One particular entry, 458.04, turns into 458.02, then 458.11, and then again 458.04, in a second or two. That’s Google.

“Do you see how fast it’s moving?” he asks. “That’s actually slow, I would say. Each one of those changes of numbers—.04 to .02 to .11 and back to .04—that’s rapid-fire change of price. But underneath that, there are probably thousands of transactions all happening at each one of those prices.”

I ask him, is the crazy speed at which it’s moving part of the problem?

In a way, yes, John says, because speed creates perpetual pressure for ever-rising financial gain. Yet even with the manual systems of 30 years ago, he says, we could have had a major disaster. The problem is that people have lost touch with one another.

“We don’t trade with each other on an interpersonal basis anymore; we trade against this screen,” John says. “When my attention is always on immediacy, and I’m a broker out there making a loan to someone I know I’ll never see again, I don’t care about that person. And the guy behind me writing the loan, he’s telling me everything is fine. So even though I know this loan is bizarre, I’m going to do it anyway, because I’m out to make a buck. Everyone in the chain is under the same pressure to produce. Not just the mortgage broker but the CEO of Bank of America, the bank itself, the lawyers who designed the collateralized debt obligation structures, Moody’s (a ratings firm), etc.”

The result is the creation of loans and other financial products that make little sense. John talks about an old friend who became a mortgage broker in the go-go years, “a wheeler-dealer, a fast talker.” John and a colleague asked the fellow if he could write a mortgage for another friend who’d dropped out of society and done nothing for years but travel, live in India, learn the ways of the Buddha. “As a joke, we said, ‘Bill, can you get him a mortgage?’ He got him a million-dollar mortgage.”

“And the guy had no income?”

“He hadn’t had any income for 15 years,” John says.

“Did he have assets?”

“Not many.”

“Wow.”

BEYOND PICKET FENCES

The financial system is like an engine that can speed up but not be slowed down. “If you build an engine that can go an unlimited amount of revolutions per minute, it will explode,” John says. When early steam engines were built, engineers understood that and added governors to slow them down. “An engine without a governor is not sustainable. But that’s what we have right now.” Attempts at governance, from the 1930s onward, have been in the form of regulations applied externally. Yet you can’t change a system effectively with rules applied from the outside. Adding rules that are fundamentally at odds with a system’s own internal guidance system is like putting a picket fence in front of a speeding locomotive. The fence doesn’t change the nature of the machine. From a systems perspective, the principle is simple:

Locate responsibility within the system.

This is what CDFIs, credit unions, cooperative banks, and genuine community banks do. These models tend to encourage more responsible behavior by employees, because the notion of serving the community is designed into their fundamental structure. Working to promote and spread these generative alternatives is a very different approach to change. It’s about moving, over the long term, toward an economy where responsibility is located within the system.

Promoting these models doesn’t immediately solve the problems of the existing financial system. New and better regulations are still needed. But if we as a culture were to more deliberately try to build the generative economy, we might accomplish two things. First, we’d give the energies of the system someplace to flow. As John put it, “You build an alternative standing alongside the existing system so that people can migrate there.” Second, we might begin to change the conversation profoundly. By creating a new concept of economic activity, the legitimacy of the current Casino Finance system begins to erode—ultimately creating the cultural readiness for a deeper shift of the whole system.

What, at its core, should that new system be about? This is a question I put to John. If he could design a new financial system, where would he begin?

“I’d start by emphasizing that money is an abstraction,” he replies. “All the instruments we trade are abstractions. If I were going to redesign the system, I’d stay closely connected to the real. It would have as its cornerstone a connection to real things.”