TEN

ROOTED MEMBERSHIP

Ownership in Living Hands

“I was at my old job at Safeway for 18 years, and I had one bonus in those 18 years, for 50 pounds (US$82),” Emma tells me. When that store closed a few years back, this 30-something woman, mother to one young daughter, took a job down the street at a Waitrose near King’s Cross station. She and I are standing inside that store and talking on this particular day, not far from the queen’s palace in London. The store is part of a chain of UK supermarkets owned by the John Lewis Partnership (JLP). Emma works as a clerk on the floor, tending the cash register and straightening shelves. For that job at Waitrose, she gets a bonus every year; a recent one totaled 2,000 pounds (US$3,264). “I spent some on a holiday in the Canary Islands,” she tells me. “It was my first holiday in four years.”

The butcher at the meat counter who steps aside to talk with me—a middle-aged gentleman named John*—wears a white linen fedora, a crisp white shirt beneath a green-striped apron, and a bow tie. He explains that they are all required to wear a hat. But wearing a tie every day is his choice. “I just feel more dressed,” he tells me. People notice touches like that at Waitrose, where pay raises are given for performance, including things such as “being a tidy person,” John says. He tells me about his sister, Carol, who also works at Waitrose and has just been diagnosed with cancer. “They’ve been really good,” he says, referring to the company. “There’s a budget set aside for people like this. She’s been off for three months, and they’re holding her job. They tell me to tell her not to worry.”

When employees at Waitrose and other JLP stores face a personal or family emergency like John and Carol faced, they can seek a grant or loan from the Committee for Financial Assistance. That committee, composed of and elected by employees, controls the special budget that John referred to, making decisions outside the chain of management. Help from that fund—plus the commitment to hold Carol’s job—took “the money side of worries away,” John says. She’s had two major operations in less than a week. “When I came in today,” he added, “the first thing the manager said was, ‘How’s Carol, how’s she doing?’”

The clerk Emma and the butcher John are owners of the store I am visiting. They are among the 76,500 employee-owners of the John Lewis Partnership, the largest department store chain in the United Kingdom, with 35 department stores and 272 Waitrose grocery stores. Revenues of this company are £8.2 billion (US$13.4 billion). That means that if this were a US company, placed into the Fortune 500 list of the largest corporations, it would settle in at around 180.1 This is higher than Monsanto and ConAgra. And it’s a company 100 percent owned by its employees—or as this firm calls them, its partners.

The business is owned solely for the benefit of those who work in it, and they possess a number of ownership rights. First, the purpose of the company is to serve their interests, the “happiness” of all its members, through “worthwhile and satisfying employment in a successful business.” Second, they share in the profits every year. And third, they have a formal voice in how the company is governed.

MEMBERSHIP: DEFINING WHO’S IN, WHO’S OUT

I’ve come for this visit because I want to see this company up close. The patterns of its ownership design seem genuine, but I want to get a better sense of it all, to see if it’s real. “[P]eople can get into the most amazing and complex kinds of disagreement about the ‘ideas’ in a pattern, or about the philosophy expressed in the pattern,” Christopher Alexander wrote. Yet “to a remarkable extent,” he continued, people “agree about the way that different patterns make them feel.”

“Go to the places where the pattern exists, and see how you feel there,” he advised.

When a pattern is made from thought, it makes us feel nothing. When patterns arise from the actual forces of a situation and successfully resolve those forces, we can feel that balance. The reason, Alexander said, is that “our feelings always deal with the totality of any system.”2

In my time at Business Ethics, I developed a pretty good nose for determining whether companies passed the sniff test, whether they seemed genuine in pursuit of a generative mission. I’d read a good bit about this company, and we’d invited one of its executives, Ken Temple, to attend one of our Corporation 20/20 meetings. I was intrigued. When I found myself in London on other business, I decided to add a few days to experience this place in the flesh, to see if it had the soul of a living company.

![]()

At the John Lewis Partnership, ownership design starts with a clear and profoundly different mission. This firm has a written constitution, printed up and publicly available, which states that the company’s purpose is to support “the happiness of all its members.” Now, let me pause and note: this is the only major corporation I’ve found that declares its purpose is to serve employee happiness. This is so, at JLP, not because it boosts returns for shareholders. At the John Lewis Partnership, employee happiness isn’t a path to some other goal. It is the goal.

And it’s more than a statement in the company’s legal documents. It’s embodied in another critical design pattern: the way in which membership boundaries are defined. If it’s true that there are no separate systems, only subsystems of the single system of the earth, it’s equally true that life depends on boundaries, on things like cell walls and membranes. No living system is a formless soup of energy. No company is a boundaryless entity embracing all living beings, equally serving all stakeholders. Each company has a clearly defined set of members.

Who is the company? Who has the right to a claim on its surplus? Who has a right to what’s left over, should its assets be sold and its debts settled? These are questions about what we traditionally call ownership—what we can call membership, to distinguish it from other aspects of ownership design.

If the ultimate perquisite of being an owner is the right to pocket some of the profit left after the bills are paid, then employees at the John Lewis Partnership are genuine owners. Each year, after the company sets aside a portion of profits for reinvestment in the business, the remainder—generally between 40 and 60 percent of after-tax profit—is distributed to employees. That’s the annual bonus that saw Emma off to the Canary Islands. Every employee, from shop clerk to the chairman, gets the same percentage of individual pay. As one manager told me, “In the worst year over the last 30 years, it was 8 percent, in the best year, 24 percent” of salary.

In a recent year, the annual figure was announced in March with much fanfare on the floor of the company’s flagship store on Oxford Street, where a partner held up a poster bearing the number “18%,” and employees clapped and cheered. That bonus amounted to about nine weeks’ pay. For a person stocking shelves and earning $22,000, it was close to $4,000. For Chairman Charlie Mayfield, pay with bonus came to £950,000 (US$1.6 million). That’s a handsome sum by any measure. But it’s modest compared with those of S&P 500 CEOs, who with stock options took home an average of $10 million the same year.3

Profit sharing at the John Lewis Partnership is seen as good business practice. It forms part of what executives describe as a “virtuous circle”—profit comes back to partners, which motivates them to provide excellent customer service. It’s the way that private enterprise is supposed to work: if you help create company success, you share in the financial rewards. Employee ownership at JLP does indeed contribute to notable commercial success. One study of 20-year performance among major retail competitors showed that the John Lewis Partnership ranked “high or top in profitability and productivity.” It found, in addition, that “the human side of the business” was “of major importance” to that success.4

FIRMS AS LIVING COMMUNITIES

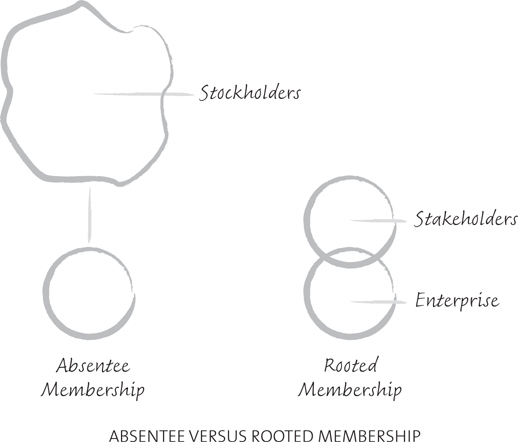

In addition to Living Purpose, this firm employs the second design pattern of Rooted Membership: ownership in the hands of stakeholders intimately involved with the tangible workings of the enterprise. Rooted Membership is a key aspect of bringing companies back to earth—rooting them again in the real economy. It arises from a vision of companies as living communities of human beings, not simply as shares of stock rising perpetually in financial value.

There are many ways to create Rooted Membership. In credit unions and cooperative banks, membership is in the hands of customers, depositors. Some cooperatives root membership in the hands of suppliers—like Ocean Spray, a big cooperative of growers. At Hull Wind, membership is rooted in the community, through municipal ownership of the town’s electric facility. Some generative companies, like S.C. Johnson, root membership in the hands of the founding family. These are all varieties of stakeholders, those with a stake in the real life of the firm. John Lewis Partnership roots membership in the hands of employees. Employees are the firm. Ken Temple puts it to me just that way: “We define ourselves simply as all our employees. We see no distinction between the business and its people.”

When JLP draws a boundary to define who’s inside the firm, it draws that boundary around employees. Capital providers, on the other hand, are outside the perimeter of the firm. They are suppliers providing capital, not members of the firm. This arrangement at JLP corrects an oddity in our economy that we rarely notice: that in extractive enterprise, the people who go to a company every day and do its work, the employees, are considered outsiders. Those who never set foot in the place, the stockholders, are insiders.

With the Absentee Membership of publicly traded companies, the soul of the firm is outside itself, trading hands thousands of times every second in capital markets. This makes a firm, in Alexander’s terms, divided against itself. It shows how the traditional view of property is potentially a deadening concept. In the classic view of property rights, the source of life and vitality is the owner. What is owned is subordinate, with no will or integrity of its own, subject entirely to the master’s whim. In William Blackstone’s words, the owner possesses “sole and despotic dominion” over that which is owned.

In corporate law, this tradition of thinking makes the relationship of employer to employee one of master and servant. In common law tradition, this pattern of relationships involves a one-way duty of loyalty. The employee owes a duty of loyalty to the employer. But the employer owes no loyalty to the employee. The employer can work employees harder and harder, with no obligation to share with them the fruits of their own labor. To the contrary, employers traditionally aim to pay employees as little as possible and can dismiss them at will. This master–servant relationship arises all too easily from the design of Absentee Membership and Governance by Markets. These patterns are at the root of some of the most destructive outcomes of modern capitalism.

One contemporary result is the increased speed-up in workplaces seen across Europe, Japan, the United States, and elsewhere in recent years.5 In an interview with Strategy+Business magazine, Margaret Wheatley said that in recent years she’d noticed increasing levels of anxiety at formerly progressive workplaces, with everyone working harder yet seeing years of good efforts swept away. People are required to produce more with fewer resources, she said, and “new leadership is highly restrictive and controlling, using fear as a primary motivator.”6 The reason is that the forces in control are outside the life of the firm, in capital markets, which are already swollen with excess yet demand still more, every quarter.

This is a very different situation than at employee-owned South Mountain Company, where the people who experience the pressure are able to control it. Both results trace back to how the boundaries of a firm are drawn. Is there Absentee Membership—with ownership disconnected from the life enterprise? Or Rooted Membership—with ownership in living hands? Is a company seen as an inert object or a set of living relationships? Grappling with this distinction is about more than words written in a corporate charter.

Generative design begins with relationships.

It’s a human process. For when we are no longer removed from the scene—no longer focused on the abstractions of capital markets or legal theories—but are instead in intimate relation with others doing the work of a single real enterprise, it’s hard to avoid that most human of imperatives: fairness.

A GUIDING STAR OF FAIRNESS

When people who do the work of a company are in control of their own fate, they’re more likely to be treated fairly and, as a consequence, to feel alive when they go there. I feel this at the John Lewis Partnership. In the management offices of the Peter Jones department store—back behind the men’s underwear department—I sit at a long table crowded with eight or ten workers one afternoon, listening to person after person talk about their long family history of working at this company.

Janice says she’s been there 28 years. “I come from a partnership family,” she tells me. “My father worked here. My son works here. My sister works here. I went to my first partnership function when I was two.”

Andrew’s story is similar. “My sister’s friend came here; then my sister came here; then I came here,” he says.

An assistant registrar,7 Bob Rosch Iles, tells the story of having to close a warehouse operation and how everyone was given the option of taking a job elsewhere at the company. Those who left received eight weeks’ pay, were allowed to take an early pension, and were given help from JLP staff in drawing up a résumé. He talks about how one recovering alcoholic who’d been with JLP for 12 years was assisted in finding work with a train service. “The man was on psychotropic drugs and was quite vulnerable,” Bob says. “I offered to walk him down the first day on the job but didn’t need to. I called him a week later and found he was delighted he could get reduced fares on the train.”

![]()

After conversations like these, I lose interest in my sniff test. I want to know more about what makes the John Lewis Partnership work, how it all began. Peter Jones was the seedbed of it, for this is the store where the company’s principles of democratic ownership were first developed. Earlier in the day, I’d arrived for my interviews through the employee entrance to Peter Jones, which has a legend inscribed in stone above it: “Here is Partnership on the scale of modern industry.” Something remarkable, at large scale, is indeed at work at this company. And it began small, in one human heart.

The company’s mission was first articulated by its founder, John Spedan Lewis. As a company booklet explained, his “guiding star was a personal vision of ‘fairness.’” Spedan, as he is commonly called, was born in 1885 to a wealthy and famously dictatorial father who ran a draper’s shop in London, which he named after himself, John Lewis. He’d done so well with it that he purchased another shop, Peter Jones. Young Spedan was dismayed to learn that his family, as owners of those shops, earned more than all their workers combined. As he wrote later, it seemed to him that “the present state of affairs is a perversion of the proper workings of capitalism,” and that “the dividends paid to some shareholders” for doing nothing were obscene when “workers earn hardly more than a bare living.”

He determined to show that there was another way. Working for his father, he introduced new systems into the family stores—like shortened working days, additional paid holidays, and a staff committee. As his father began to show alarm at these practices, the two quarreled. The father struck a bargain with his son. Spedan could have total control of the money-losing Peter Jones if he kept his hands off the other store. That was 1914. Spedan went for it and told his staff that if the store became profitable, they’d share in the profits. Within a few years, he made good on that promise. In 1920, he introduced the firm’s first profit-sharing scheme, as well as a representative staff council. After his father’s death, he received total ownership of both stores. Soon afterward, he created the first constitution. Within a decade, he began turning ownership over to employees, and in 1950, he relinquished his remaining interest. For his ownership transfer, he was paid over 30 years, without interest.8

It wasn’t only company ownership that Spedan passed to employees. Eventually the partners came to possess Leckford Abbas, an ivy-covered manor with an oak-paneled library and billiard room that had once been Spedan’s country home and is today run as a hotel for partners. The partnership also now owns the entire Leckford Estate, with a dozen cabins, two golf courses, two swimming pools, tennis courts, and fly-fishing on the river Test. This is the family home where the eccentric Spedan—an avid naturalist—had once brought a mini-zoo and kept peacocks, meant to live in the garden, which often escaped into the village to cause havoc. Partners stay there now at modest rates. The place also serves as a working farm, supplying Waitrose with barley, oats, organic milk, apples, mushrooms, and free-range eggs. It is one of five holiday centers run for partners.

This is generative design in fully developed form—unfolding over nearly 100 years, working out its design in ways that keep it true to its founding ideal of fairness. There is no mistaking the fact that moral ideals are at the heart of this major corporation. In 1954, Spedan published a book, Fairer Shares, in which he made clear that his essential aim with the John Lewis Partnership was to create “an experiment in industrial democracy,” which he believed to represent, as the subtitle said, “a possible advance in civilization.”

The fairness that Spedan sought was not a flat equality of the sort that communism attempted or that I’d seen tried at a worker co-op. The Williamson Street Grocery Cooperative in Madison, Wisconsin, where I served as president of the board for many years, at one point paid everyone the same—from the general manager of that million-dollar store down to the person newly hired to stock shelves. Those of us on the board led a drive to pay the manager more, to raise that person’s pay to closer to industry standards. The staff dissented vigorously, and more than a year of tumult ensued. But ultimately, the co-op did institute differential pay, raising the manager’s pay substantially. As many of us insisted, it simply wasn’t fair to pay everyone the same. The manager deserved more. Fairness isn’t the same as equality.

“Wide differences of earnings seem necessary, if possessors of uncommon ability are to discover it in themselves and to develop and exert it as the common good requires,” Spedan wrote. “But the present differences are far too great,” he continued. “Our world of millionaires and slums is more and more volcanic.” Yet in Spedan’s mind, taxing away some profits and giving a bit to workers through food stamps or welfare was an inefficient design. Better to get wealth in the right hands in the first place, through a fair distribution of the profits that workers themselves create.9

Pursuing that didn’t mean Spedan’s family gave up its wealth. Spedan was paid for his ownership shares a sum that Ken Temple estimates would today total more than $100 million. Just as Spedan had no interest in renouncing wealth, he also was not interested in dispensing a bit with a benevolent hand. He was after fairness on a large scale—the scale of major industry—and in his broader vision, the scale of civilization itself. It is fairness designed into how businesses are owned and run.

BEYOND MONARCHIES OF CAPITAL

In the words of modern-day philosopher Martha Nussbaum, creating this kind of advanced social order is an issue not of charity but of justice.10 It’s about the essential moral rightness of an arrangement that honors the dignity of labor. “[T]he supreme problem,” Spedan wrote, is the “prevention of a galling sense of needless inferiority of any kind” and prevention of that sense of “being exploited, victimized, for somebody else’s benefit.” In theory, he continued, this will be achieved in private enterprise if all the workers share “as equally as possible all the advantages of ownership, not merely profit but power, security, intellectual interest, sheer fun.”11

Drawing social boundaries as the John Lewis Partnership does—embracing every employee as a member of the enterprise—is as revolutionary in its import as the design of political democracy. In a democracy, the people are the state, in contrast to an aristocratic world, where the king is the state (in Louis XIV’s famous dictum, “L’etat, c’est moi”).

Today, the ruling oligarch in our economy is capital, for capital is sovereign within enterprise. Only capital has the right to vote inside most publicly traded companies, and only capital has a claim on profits. Capital is master. Labor is servant. The reason is the way society chooses to draw the membership boundaries of enterprise.

Social boundaries are of our own making. Redrawing them more expansively over time is essential to the movement of social progress. In the Anglo-Saxon tradition, there was a time when only white, property-owning men were considered members of the democratic polity and eligible to vote. But over time, democratic society redrew those boundaries to include blacks and women. The building of a generative economy is the next step in that historical movement. “We can get lost talking about this abstraction, the corporation,” journalist William Greider said at one gathering of Corporation 20/20. “The relationship of people to their work is one of the central next strands in the human story. It’s a story of natural rights, human rights.” Framed as an issue of human rights, a key issue might be stated this way:

Do people have a right to the fruits of their own labor?

This is a principle articulated often in the history of democracy. Thomas Jefferson defended a right “to the acquisition of our own industry.” Abraham Lincoln said, “Labor is the superior of capital, and deserves much the higher consideration.” Thomas Paine said the question was the status of the common man and “whether the fruits of his labor shall be enjoyed by himself.” Paine further articulated a vision of “every man a proprietor.” Since in the modern world it’s not practical that all people could start and own a company, the contemporary version of Paine’s ideal is every employee an owner.12

![]()

We’re approaching a historical inflection point in the United States where realizing this vision may be within our grasp, with the pending retirement of baby boom entrepreneurs. The moment of Founder Departure is about to occur on a massive scale. According to a Federal Reserve Survey of Consumer Finance, just 50,000 businesses changed hands in 2001 in the United States; but by 2009, that number was estimated to total 750,000. A wave of sales of closely held companies is beginning, and it is projected to go on for 20 years. These businesses account for close to half of private sector payroll, and in the last decade, they generated eight out of ten net new private sector jobs. According to a study by White Horse Advisors, only one in seven of these company founders expects to pass the business to family. An “age wave” of ownership transfer is coming.13

Will ownership of these enterprises flow into the hands of capital or of labor? The few or the many? With the right tax incentives and supportive social ecosystem, we could see a massive surge in employee ownership. As a company like JLP demonstrates, employee ownership can work at companies of large scale. And in both the United States and the UK, employee ownership is a model that has been shown to appeal politically to both right and left. Policies to advance employee ownership are also being adopted by governments in Cuba, South Africa, and elsewhere.14 Employee ownership may be a model whose time has come.

Yet if it’s to represent a truly generative alternative, there’s more to this design than getting the membership boundaries right. Many employee-owned companies still consider it their purpose to maximize profits and give employees no say in governance. In systems terms, simply changing the players in a game doesn’t change much. Take out every player on a football team and put in all new players—it’s still football. As systems theory tells us:

The more potent approach is to change the rules of the game.

That is what Spedan Lewis did. He didn’t accomplish this simply by substituting one group of owners for another—taking out capital providers and putting in employees. And he didn’t accomplish it simply by creating that elegant statement of purpose, about serving the happiness of employees. Living Purpose and Rooted Membership were a vital start. But something else helped create the feedback loops that brought the whole thing to life and kept it running over more than 100 years. It was Mission-Controlled Governance.