3 We Are What You Share

YOUR PARTICIPATION in social media is much more than just the individual bits you choose to share. As the online universe expands and merges with our offline lives, a whole ecosystem has emerged. Each of us has a role in that new environment, whether or not we’re aware of it, and what we choose to do with our roles ultimately will make or break the health of the social networking ecosystem.

Within that ecosystem, a number of elements are required to keep it in good health: generosity, identity, empathy, and authenticity. When one or more of these are lacking from your participation (how you share), the overall picture of what you’re about suffers, as does your ability to influence others and make change. Furthermore, your opportunity to discover and learn more about yourself diminishes as well.

Trading in Karma

Within social networks, an economy is at work, but it’s not based on money. It is instead a gift economy. Simply put, people who participate in this kind of system believe that it’s a good idea to do good things, regardless of any quantifiable return on their investment. According to Wikipedia—a fabulous example of a gift economy—this do-gooder system embraces a culture in which

valuable goods and services are regularly given without any explicit agreement for immediate or future rewards (i.e. there is no formal quid pro quo). Ideally, simultaneous or recurring giving serves to circulate and redistribute valuables within the community.1

In technology, the gift economy is most obvious in the open source movement.2 Software developers make code available to everyone to use and/or improve upon, with no monetary compensation. The understanding among open source participants is that no one of us is smarter than a group of people working to solve a problem, and we all benefit when that problem has been solved.

Early adopters of social media tools were technology folks accustomed to participating in gift economies, either through open source or Creative Commons3 licensing (which gives authors control over how their work is used, if at all, by others). Popular social network and media tools such as Twitter, Face-book, and MySpace are not open source (they are applications whose code is private and owned by for-profit businesses), but the spirit of community enhancement and problem solving is widespread among users. That community-based culture grew out of the way in which early adopters—tech-savvy people—encouraged open source principles, such as share and share alike, always include the name of the person who provided the information and/or its source, and support others by responding to requests for advice and guidance.

Social media’s facilitation of sharing, connecting, and storytelling creates a perfect stage for extending the gift economy to everyone. And within this economy, we measure our own participation through social capital. In simplest terms, think of social capital as karma: When you do good things, good things come back to you.

This arrangement is not explicit; there is no set of standards such as “Do X, and Y will happen.” Many of us, especially Americans, find it hard to wrap our heads around trading information or services without some kind of defined payback, since our grounding in market-based economies encourages us to think of everything in terms of direct transactions. If I pay you $5, you’ll give me a pint of Ben and Jerry’s. If I refinish your flooring, you’ll pay me for my labor. Even when we think of bartering, we still focus on the transactional moment: If I cook you dinner, you’ll show me how to set up a Web site.

In the gift economy, transactions aren’t viewed on a one-to-one basis; a collection of actions over time is what establishes a person’s social capital. That holistic view of what people’s actions say about them contributes to the overall health of the social media ecosystem. What kinds of actions and assets make someone valuable? Tara Hunt, author of The Whuffie Factor: Using the Power of Social Networks to Build Your Business (Crown Business, 2009), presented six factors at a Women Who Tech panel discussion.4 I’m giving her key terms, followed by my interpretations of her definitions:

Connections: Who do you know? Not just important or famous people, either. Are you connected to lots of different kinds of people who can complete different tasks?

Reputation: What are you known for? What do people say about your expertise?

Influence: Can you move groups of people, small or large, to take some action?

Access to ideas, talent: Beyond your own skill set, do you have ways of reaching out to others with talent and knowledge?

Access to resources: You may not be able to fund a particular project, but do you know people who can? Do you have ways of generating physical support?

Potential access: Will your access to resources and talent stay static in the future, or will it continue to grow?

Saved-up favors: We’re not writing down every good deed, but do people remember you for the ways that you help others? Your own generosity is incredibly important. Is your goodwill with your social capital part of your reputation?

Accomplishments: What awards have you won? What concrete recognition—papers or articles published, etc.—have you received for your work?

All of the facets of your social capital together make up your net worth in the gift economy.

As you accumulate social capital, you spend it, reinvest it, and accumulate more. What follows is an example of a social capital growth cycle; keep in mind, though, that it’s generally much bigger than this Y-follows-X example. It’s an ecosystem, not a linear argument.

Let’s say Julie is well known in her social circle as an expert on craft beer. It’s a great hobby, and every time she samples a new beer, she posts a short review as a status update on Face-book, which leads to lively discussions in the comments section with her friends. Having conversations is how she builds her reputation.

Friends know that she’s a microbrew aficionado, so they post links to her Facebook profile, pointing to new beer releases and brewpubs. She takes time to thank them and lets them know later if she checked them out. Thanking her friends and responding to their posts also builds her reputation, because we all like to be appreciated, right?

Those folks start sharing her reviews with other microbrew fans, and those fans ask to be Julie’s friend on Facebook so that they can read her information firsthand. When she accepts new friend requests, she’s building her connections and her access. A few months into this process, Julie finds out about a micro-brew festival near her town that is accepting nominations for judges. She asks the people interested in her beer posts to vote for her (using some of her saved-up favors). When she wins a spot, she offers to host a local microbrew meet-up at the festival, which puts goodwill back into the system, and it also helps get the word out about the festival. Her social capital increases.

While I’m sure that every one of you has expertise to release into the world, it’s not necessary to specialize in one thing. If you’re known in your social circles as a go-to person for help, guidance, or advice, you’ll flourish in social media. If you’re not (yet), these tools make establishing expertise incredibly easy. They’re built to help us operate in the gift economy effectively and efficiently.

Be careful, however, of exploiting the gift economy—either purposefully or accidentally. Doing so can make you a pretty bad social capitalist; you don’t want to be the ExxonMobil of social capitalism. You’ve probably already experienced good social capitalists and bad social capitalists in your daily wanderings throughout the digital world. Think about a listserv or e-mail group you belong to and some of the participants there. Let’s say you belong to a group devoted to baking. How do you feel about the members who share interesting links to articles with healthy substitution tips, or who answer questions about ingredients, or who just generally move the conversation along? Now think about the people who consistently post pictures of their own cookies, or who ask for advice but who never answer questions, or who consistently drive the conversation back to their own kitchens. . . . You sense the difference, yes?

The same is true with these emerging tools—it’s hard to build out a network with a bunch of one-way dead-ends. Humans gravitate toward people and groups who are supportive and who aren’t (entirely) self-centered. In the online version of that gravitation instinct, it’s easier than ever to find those people.

What’s critical to understand is that the behavior we’re seeing in these online communities is not that much different from what we see offline. Each of us has been working with social capital all along, but now that we have tools like Facebook and Twitter that map and document our social interactions, our social capital is much more transparent.

It’s not just clearer to us how we’re interacting with other people, but it’s also more obvious to those around us what each of us has to offer and how we operate. Jessica Clark, research director for American University’s Center for Social Media, says that she had been studying the role of social networking tools in politics for a while, but she didn’t really understand their power for everyday life until she met Alex Hillman in 2007.5 Hillman, a Philadelphia-based web developer, helped cofound Independents Hall, a “coworking” space where freelancers can rent desks so that they don’t have to work in isolation at home or in coffee shops.6 “The whole vibe of Indy Hall was open source—the assumption was that shared space would lead to useful information sharing and creative collaboration,” Clark observes. Hillman himself conducts much of his life online, enthusiastically sharing both personal and professional information via Twitter, blogs, and discussion lists. “His energy and openness was infectious; it offered inspiration to open yourself up and see what you could give back to communities that you’re part of,” she noted.

Displaying trust, kindness, and empathy—all values that social capital and the gift economy are based on—has never been easier, or more important.

On the Internet, Everybody Knows You’re a Dog

Thanks to social networks’ transparency, it’s also more important, and more accepted, to use your real name and identity. Identity is a key component of your work in the ecosystem. When you act anonymously, your reach is limited because you’re not leaving a record of your actions. When you participate publicly, your actions leave a public trail. It’s still fine in some cases to build your relationships and social capital under a pseudonym (and there are a few cases where it’s necessary). As divisions between online and offline life dissolve, however, it has become much more valuable to combine many of your identities into one powerhouse.

Contributing our opinions and experiences to public conversations using our real identities plants a stake in the ground, and on the public record, wherever it may be kept, that validates the identities we create for ourselves online. We’re still getting used to the idea of using our real names and pictures—it wasn’t that long ago that no one ever did that, and anonymity was all the rage—but by doing so, we’re able to use our identities to create trust with one another. When we trust the people with whom we’re sharing details of our lives or opinions, we build collective empathy. It’s easier to trust a person online with a real name attached to a screen name, a picture instead of an icon, and a running log of the person’s interests and comments. That trust and empathy creates the building blocks for wider change, as we’ll see later in this chapter.

We arrived at this juncture of identity and trust as a result of gradual adoption of Internet technologies in our daily lives. But in the early 1990s, it was widely popular to claim that everyone online could pretend to be anything they wanted. The famous 1993 New Yorker cartoon by Peter Steiner featuring two dogs chatting about Internet identity (“On the Internet, nobody knows you’re a dog”) pretty much sums up the ethic: We can all hide behind the giant curtain of technology.

The Internet removed physical constraints that our silly human bodies put on us, as well as all kinds of social mores that prevented us from saying and doing what we wanted. But creating an online identity was still the purview of nerds and geeks back then. By the mid-’90s, more people were joining discussion lists and chat rooms, but mostly under assumed identities, with clever nicknames that represented slices of their identities—GiantsFan4Ever or KnitterManiac2002. Sometimes the nicknames represented more private desires and alter egos.

In 1995, during my college fangrrl days listening to the Bare-naked Ladies (a band. Canadian. Humourous, with an extra Canadian u!), I became a regular participant in the BNL channel on Internet Relay Chat protocol, or IRC.7 The online chat service came out in 1988, making it one of the oldest online communication services in the book. My nickname, to the best of my recollection, was “deannabanana.” It was what my friends called me in jest; I felt like it was close enough to who I was but eased me out of the scary step of Revealing A Last Name.

By the early 2000s, more people were comfortable with using their real names, but privacy and security concerns remained. Never before had we experienced such unfettered access to other people’s lives, and no one knew exactly how it was going to play out. People were concerned with being “outed” in one way or another, so we still concealed the more personal and quirky parts of our lives. It was not socially acceptable, for example, to attach hobbies to one’s public identity. Letting people know that you were a fan of a sci-fi series or that you obsessed nightly over Japanese garden design was not necessarily a good thing.

As the Internet evolved, and as more people started using it for different purposes, some of the fear around revealing different parts of oneself lessened. Purchasing products online, for example, required a new level of trust when giving out credit card information and mailing addresses. Susan Mernit, a web strategist and founder of Oakland Local, suggests that online shopping especially helped build trust in the Great Big Ether: People gave their credit card numbers and addresses to systems online, and, largely, nothing bad happened to them.8 Additionally, businesses went to great lengths to ensure that people had a safe shopping experience and maintained control over their identities and how much personal information they wanted to share.9

Our willingness to use our names is also accelerating a trend toward more authenticity. Sharing every last tidbit isn’t required (or even desirable), but there’s more opportunity to share information that previously might have been saved just for people we already know. We belong to numerous social circles—work, politics, hobbies, sports, religion, school, neighborhood—and now that everyone’s lives are overlapping, the overlap is OK because it’s happening to all of us at the same time.

If I were seeking to meet other BNL fans today, I wouldn’t necessarily search for a dedicated fan site. I’d start with an online social network I already belong to, like Facebook, and join a BNL fan page or group. The online network is already in place, and, more important, people’s identities are already validated by these networks. We are already participating as ourselves. No more “deannabanana” hanging out in the chat room; now it’s Deanna Zandt joining the fan page or friending the band.

Engaging with one another online has the wider cultural benefit of inspiring more civic engagement offline. Studies show that young people who participate in online communities are more likely to take part in offline civic activities later in life. This is the case even when their online interactions are purely social or for enjoyment (such as joining a Barenaked Ladies fan site). Even in these spaces, teens are developing real skills, including learning how to assess and share information.10

Using your real name yields many benefits, starting with social capital. By associating your knowledge, opinions, and sense of humor with your real identity, you’re helping to build a profile of who you are. Many social networks get indexed by search engines like Google, so your posts will come up when people search for you or the topics you’re posting about. (Of course, you will still want to keep some things private, which you can do by investigating and adjusting your privacy settings.)

Developments in online security and privacy, as well as the normalization of a variety of Internet activities—such as online shopping, chat, and social network participation—have reached a point where folks are becoming comfortable with revealing parts of themselves. And our values are inherent in those activities we participate in, from the overtly political, like joining a Facebook Cause that all of our friends can see, to the more subtle, like complaining about working two jobs and still not having health care. Everything we choose to share doesn’t just represent those individual events, but also contributes to the larger picture of what our values and experiences are.

Those contributions create trust between the members of any given network, and the combination of high trust and valid identities enhances the depth, breadth, and overall health of the social media ecosystem. We start to share more of what’s important to us (as we’ll see in the next section), and through the trust we create with our real identities, we foster empathy and understanding.

Your Life Makes History

Besides being beneficial to you and building your social capital, sharing yourself and your life experiences is a highly political act.

Remember that old adage, “The personal is political”? It’s never been truer than at this moment. Each bit of information that we share with others becomes, collectively, an act of political significance. “Politics” is not just about candidates, elections, and ballot initiatives. Politics is the art and science of influencing or changing any kind of power relationship: the cultural norms by which we act; the laws that govern us; the expectations we experience based on our gender, race, class, sexuality, abilities, and more. When I talk about political work, I’m talking about challenging and radically redefining those power relationships, using the tools that social networks provide.

It’s easy to point to the “what I had for breakfast” phenomenon and decry social media as nothing more than a narcissistic endeavor. I understand where the impetus to dismiss the posting of these minutiae comes from—certainly no one should be terribly interested in the details of our daily lives, not when read as individual events. It’s the bigger picture those events make up that is so exciting.

Step with me into the Wayback Machine for a minute, to a supposedly simpler time when behavior was neatly compartmentalized: the 1950s. Now, I wasn’t alive during that time, but I’ve seen enough of those “health and hygiene” movies to know what the deal was.11 Using the ’50s as a metaphor, let’s compare Then and Now.

During that time, men worked, and their work stayed in the work sphere. Upper- and middle-class women stayed home and took care of the kids, heading up the domestic sphere. Publicly, white men were in charge of just about everything: government, media, and other public domains. There was little crossover between spheres, and anyone who didn’t fit the prescribed white, heterosexual model was denied a voice.

I think we can safely say that this was one of the most repressed times in American history.

Fast-forward to the rip-roarin’ times of social media. It’s no longer a requirement, in most cases, to keep work and personal lives separate. With the advent of mobile, always-on technology, it’s sort of impossible. As people take part in social media, different parts of their lives start to manifest in a more public way.

Look at any of your friends’ Facebook or MySpace profiles, and you’ll see a pretty wide swath of things they’re interested in (music, movies, what have you), as well as causes and social/political situations they care about based on what they’ve listed in their interests, or what groups they belong to, or what they’re a fan of. With whatever we share, we are saying that we trust the people around us with this information. And, in most cases, that trust is rewarded, as people in our communities show, in various direct and indirect ways, their support for what we share. By showing support, we each become trustworthy to one another—all of which builds our social capital and leads to pipelines of empathy and understanding. This, of course, assumes that people are fundamentally good, trustworthy people. I’m hopeful they are,12 and that hope is a fundamental principle driving my work for change.

Empathy—the ability not just to have concern for, but to share another person’s emotions—develops when we participate in each other’s lives. Prior to social network technology, it was difficult to stay loosely connected to a large number of people, and thus difficult to have much empathy for people outside of our tightly knit groups. In early Internet social settings, such as forums, anonymity fueled bad behavior and ultimately distrust.

Now that relationships and trust influence how we receive and manage digital information, we’re becoming more connected, and thus we have the capacity to be more empathetic. That trust-created empathy will lead us away from the isolation and resulting apathy that we’ve experienced as a culture, arising from the 20th century’s focus on mass communications and market demographics.

Here’s a story about how building trust through social networks has worked for me. A couple of years ago, I spoke at a conference in northern California. After my song and dance, Leif Utne, the vice president of community development for the software company Zanby, came up to introduce himself. He was working on a project that he wanted to get my employer, Jim Hightower, involved with. We exchanged contact info and became Facebook friends; later we started following each other on Twitter.

About a year and a half later, Leif messaged me to say that he was coming to Brooklyn for a visit and wanted to know if I’d like to get coffee. Sure! Of course! When we sat down a few days later, I asked him how the baby was—he and his wife had spent a long time adopting a baby from Guatemala, and Leif had even lived there for ten months. He lit up and showed me recent photos, and then asked how my dog, Izzy, was adjusting to life in Brooklyn. I had adopted her from a rescue organization, and we laughed at how the processes for adopting dogs and children were eerily similar.

Leif asked if he could show me a new online service that he’d taken a job with, one that would give groups a way to connect their memberships. Absolutely, I said. We did a run-through, and he talked about some of his company’s successes. I started thinking of clients who could really use something like this tool and offered to put him in touch with them.

My online friendship with Leif is significant for several reasons. Social media enabled a kind of “identity authentication” between us. I was aware of Leif’s family’s work with the Utne Reader before I met him, but being connected via social media gave me insight into some of his values and interests. And vice versa. More important, though, it allowed us to collect seemingly unrelated fragments of information about one another over time, and to create a wide-angled picture of the other person with those fragments. Technology writer Clive Thompson calls this phenomenon “ambient awareness” of the people around us.13

It doesn’t impact my life at all to know that Leif is heading to the airport, and he probably doesn’t care that I spent an extra 30 minutes with my dog in the park this morning. But over time, we are able to see a portrait of one another’s lives take shape and feel connected. While Leif’s trip to the airport doesn’t affect my daily life, if he misses his plane, I feel bad for him. There’s the empathy, simply by being aware of another person’s “mundane” activities. Our portraits of one another facilitated an in-person conversation that otherwise would have been stilted and awkward:

“So, you, uh, have kids?”

“No, you?”

“Yeah, one. A little boy.”

“Uh-huh.”

Instead, we were able to tap into what we care about pretty quickly, and the landing into the “business” end of the meeting was much smoother.

Admittedly, experimenting with what it means to share different parts of our lives can sometimes be uncomfortable. Chip Conley, the CEO of a family of boutique hotels in northern California called Joie de Vivre,14 offers a case in point. In 2009, he wrote about the fallout from photos he posted to Facebook from his latest Burning Man15 trip. Some workers were surprised to see Conley in a tutu and a sarong.16 The complicated part wasn’t that he didn’t want them online, or that his investors or board members didn’t want them online; it was that some employees struggled with seeing their fearless leader show a carefree side of himself that didn’t “fit” with the standard work environment. We’re all still determining what we each individually consider acceptable amounts of information, as well as what we’ll tolerate organizationally and culturally.

Thanks to the alienating effect of mass communications, our ability to converse directly with one another, and to engage with the larger culture in a meaningful way, has withered. While no one has figured out a precise formula for what amount or mix of sharing creates empathy, presenting real pictures of real lives indisputably frees us from our pigeonholes. Social networks give us the opportunity to reengage with one another.

Diving In

Before we float along in too much theory, let’s discuss some concrete tactics for sharing. Many people who are just starting out have trouble deciding what to post. A flat-out easy beginner’s guidepost comes from the illustrious Susan Mernit, who once told participants in a workshop we cotaught: “If you’re wondering whether you should post something or not, you probably shouldn’t.”

The genesis of this axiom comes from a key principle of social networks: Authenticity rules. Again, the idea is not to share everything under the sun, but to make meaningful connections based on the substance of who we really are. Social media “gurus” and “mavens” often slip “authenticity” into smarmy marketing blog posts. Ignore them. They are not the guides you are looking for. But authenticity is.

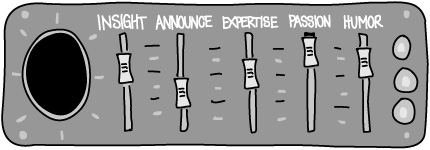

My cousin Cheryl is a therapist in Washington, DC, and she told me about the stereo equalizer model of relationship intimacy. Reliability, trust, availability, etc., are the main components—skew one of those bands outta whack, and the whole mix is off.

Social media authenticity works much the same way. It’s a mix of personal insights, professional announcements, expertise (whether about a job or a hobby), passion, lots of opinion, and humor. It takes some experimentation to figure out what mix sounds right to you.

Authenticity is a mix of different elements.

The experimentation is why Susan’s advice is so dead-on: What you perceive to be good, what you feel comfortable with, that’s what people will pick up on as they share in your experiences.

For people who are largely private folks who don’t want to tell the world about the silly stuff their kid just did, that’s fine. Share your impressions of an article related to your work. You don’t have to use your most conversational voice, either. You can maintain a fairly professional tone (though do try not to be emotionless) and still come across as engaging and insightful. The mix is what’s going to make your voice sound good—to you and to others.

For some people, it’s easy to share personal news and events. Me, I have no bones about tweeting funny things my mom says, details of a party, or (loads of) pictures of my dog. It’s a way for me to keep a running log of things that are important to me. That said, my guidepost is to not share things that would make me feel vulnerable, like details of my dating life. I share information once in a while about my health, either to reach out for help or to show solidarity with others, but I consciously keep it to a minimum—simply because that’s what feels right to me.

The experimentation can be uncomfortable to start with, but know that it’s OK to make mistakes here and there; social media is quite a bit more forgiving (and forgetful) than more traditional forms of media (and, I would add, also more forgiving than blogging).

Worried about it all being Out There? Jaclyn Friedman, an author and coeditor of Yes Means Yes!, made a great point in a workshop I was leading about how our perception of social media is rapidly changing, similar to how our perception of tattoos has changed in the last 50 years. Think about the attitudes toward a person who got a tattoo in 1960, versus attitudes now. It’s the same with social media. Ten years ago, someone getting a swig of TMI17 via Google search results might have had an adverse reaction. Today, seeing something a little off-topic in a Twitter stream is not as big of a deal.

That said, I do want to mention that some folks are in jobs where more attention needs to be paid to privacy and security (you know who you are). Different parameters are in play when working on establishing your mix, but you shouldn’t keep yourself out of social media altogether. Almost all of us are already represented online. Ever try Googling yourself? Social media sites generally appear within the top 10 search results; you should do your best to influence how you appear, even if it’s to show that you’re largely a private person.

How Sharing Inspires Social Change

When we share who we are—what life is really like for most of us—we are committing small political acts. We all receive cues from the culture(s) around us to indicate how we should act, based on our gender, or our sexual identity, or our race. Often those cues are biased and stereotypical, and don’t represent the reality of our identity. When we share snippets and nuanced insights, we have the opportunity to reject those prescribed expectations and to share the real deal with others. That exposure to other people’s thoughts and opinions is almost like a new version of consciousness-raising for the digital age.

Consciousness-raising is an example of how sharing our experiences and rejecting cultural expectations has worked on behalf of social change in the past. For younger folks (like me) who might not know what it is, consciousness-raising was a big part of the U.S. feminist movement in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Many women were experiencing social oppression in isolation. And if these experiences remained individual and isolated, it would be difficult, if not impossible, to organize a movement to change them. Many women were not involved in the participatory politics that were so popular at the time, and some found traditional models of organizing off-putting.

Thus arose this idea that women—mostly white, middle-class women, that is—could get together in small groups in their towns and cities, and speak freely (“rap,” no joke) about aspects of their lives that they found difficult or troubling. Other women in the room found commonality with those experiences, and soon everyone would (hopefully) become conscious that there was a systemic problem that extended beyond their own lives. The realization of widespread struggle would (again, hopefully) lead to political action and involvement, often through more traditional structures.

This model wasn’t without problems—as mentioned, consciousness-raising was popular among middle-class white women, which marginalized the voices of women of color and queer women. (We’ll talk more in chapter 5 about how online consciousness-raising can also have a marginalizing effect if we’re not careful.) Put simply, though, we see that sharing personal experiences has a profound effect on social change. The Not In Our Town18 project, for example, started out as a documentary film to address how the citizens of Billings, Montana, banded together to address hate crimes that had happened in their midst. It has evolved into a full-fledged national movement built on the power of storytelling against hate. Sharing our stories matters. If I’m posting grumblings about pay problems at my job, and someone else in my workplace sees that and responds, that could be the beginning of labor organizing for that company. If I see people celebrating the passage of marriage equality laws in their home state, it might inspire me to find out what’s happening in mine.

The result is not always a clear path of inspiration to direct action, but the shifts in consciousness can make a profound difference in how we and our contacts interpret and respond to issues. Moreover, we can create overlapping public conversations between groups of people that otherwise in the past might have remained isolated from one another, thanks to the racial, class, and gender divisions our society has in place.

An incident that occurred during the summer of 2009 offers an illuminating example of how overlapping social spaces online can support change efforts. A private country club in Philadelphia banned a group of African-American children from swimming in its pool, even though the kids’ camp had paid for their swimming privileges.19 Capturing the public’s shock and outrage, comedian Elon James White, host of the popular web series “This Week in Blackness,” opened an episode with the words: “Hi, I’m broadcasting live from 1952 . . .”20

Social networks lit up with discussions of the incident. Acting on simple moral outrage is a start, but when everyday people contributed their own histories of childhood discrimination, much more fundamentally painful and ultimately consciousness-shifting, deeper work began.

When I heard about the incident, I signed petitions, I passed the info along on Twitter and Facebook, and I talked about it with my friends, both online and off. As the dialogue continued, people started to share stories on Twitter and Facebook about the first time they had been discriminated against. I read story after unfiltered, unedited story, written by friends. The stories were devastating; so was the fact that I hadn’t heard them before.

I realized that without social media, I probably never would have heard those stories. Or I might have heard one of them, isolated from others. Being white, I have never been a victim of racism, and because many of my friends are white, they haven’t either. Before the emergence of social media, I most likely wouldn’t have found myself in the company of a group of people of color sharing their childhood discrimination stories so openly and honestly.

To share that kind of intimacy requires some sort of explicit or assumed “safe space”—a forum of sorts, where one can express views without threat of abuse or harassment. Safe space requires a tremendous amount of trust, and that trust allowed the people sharing the stories with each other to extend the conversation past the sound bite moments that get played out in media and other traditional public forums. “Usually when people of color talk publicly, it’s about our feelings, our mistakes, and being frank about our shortcomings,” says Ludovic Blain, director of the Progressive Era Project and a longtime social justice activist. “Often when white folks speak in the same setting, it’s about their initiatives and how they’ll make it right. That’s perverted. In the case of the racist pool, the scene was the same: people of color discussing heart-wrenching issues in front of whites. But those people were also doing a rare thing—publicly discussing what whites had done wrong.”21 The empathy based on shared experience, combined with trust that the conversation would be productive, brought this moment to a more necessarily intense place.

Additionally, people decided to share their stories for many reasons: to release a painful memory and get it off their chests, to connect with others who had experienced similar racism as children, to potentially educate those who needed to hear their memories, and more. Thus, the voyeuristic aspect of the experience was strong. My whiteness was hidden for a moment (via my silence, not sharing a common past experience), and social networks allowed me to enter a conversation that otherwise might have been altered by my presence. I was able to benefit regardless of whether the sharers intended for me to, and that cultural voyeurism needs to be clear when discussing issues that deal with bias around race, gender, class, and other kinds of privilege.

Social networks facilitate overlap among groups that previously had no opportunity to engage in dialogue. Even though humans will always be drawn to others who they think are like them in one way or another, sharing powerful stories with one other has the potential to reach across social boundaries and create new kinds of safe spaces. Safe spaces have traditionally been organized around identities and experiences—women’s groups, ethnicity-centric groups, queer groups, etc. Now we’ll have the opportunity to create new criteria for trust that will ultimately contribute to new safe spaces.

I received an education that day. It’s one thing to read stories in the newspaper and get upset; it’s an entirely different, deeper experience to read the words of friends and colleagues sharing intimate, painful moments in real time. Those shared moments left me feeling not just more passionate about addressing racism, but also more willing to hear what’s being said when I need to listen.

Change does not, and will not, happen in isolation or on an individual basis—we need each other to produce results. As we start to explore with social media, we have the potential to deepen our understanding of one another’s life experiences, and of ourselves. Telling our stories in real, authentic ways becomes critical to moving others toward progress and change.

Authenticity, the Great Equalizer

We’ve figured out, then, that shared experience is a fundamental building block for social change movements, and that social media makes sharing experiences, as author Clay Shirky puts it, “ridiculously easy.” But it’s not enough to put random things out there. What you share in social networks needs to come from a real place in your personality: your own experiences, opinions, hopes, and fears. It’s those authentic tidbits that are going to create connections of empathy and trust with other people, and ultimately create an antidote to the narcissism and political apathy that mainstream culture has pushed us toward.

Let’s discuss for a moment the nature of the authentic self. Many people I’ve spoken with are questioning whether participation in social media is a performance. And if it is, does that mean it’s any less authentic? My opinion is that yes, it is a performance. But so is writing this book. And so was the conversation I had with my mom earlier this evening. And so was the casual hello I said to my neighbor this morning.

In short, everything we do outside of ourselves is some sort of performance. We have myriad rumblings inside our brains at any giving moment, but before our thoughts become words and actions, we initiate an often-unconscious series of deliberations about what we choose to do. That’s filtering ourselves at a basic level and creating some sort of “performance.” So, let’s look at that word differently. Bob Holman, poet and proprietor of New York’s Bowery Poetry Club, asked me to reconsider the definition of “performance” that I’m using. “We think about ‘performance’ as something that’s planned and rehearsed, which somehow makes it less authentic to us,” he said. “But what if we thought about ‘performance’ like how we apply it to cars, or horses? How we then judge performance changes radically.”22

In other words, let’s not think about performance as something planned, practiced, and thus potentially inauthentic (because everything we do is planned at some level—“planned” is not a measure of authenticity); rather, let’s frame performance as an experience whose quality we can determine by thinking about how well—how authentically, perhaps—the experience worked for us. Did the performance touch us emotionally? Did it engage us to take action? How are we different now that we’ve shared that experience with other people?

If we go with this new definition of performance, we no longer question whether our posts are “real” or “rehearsed.” The real point is quality: How “good” are we at expressing our true selves? If our networks feel that we are presenting ourselves authentically, then we have succeeded.

How authentic we are to the people around us matters more than ever. In a thriving social network ecosystem, increased amounts of authenticity are another important ingredient. It’s not enough to just present your identity and hope for the best; people connect to one another when they feel trust, and authenticity is a key component toward building trust.

Know Your Network, Know Yourself

Authentic interactions with one another also provide us with a way to explore and make connections in the social ecosystem in entirely new ways, as we share experiences and perceptions about how the world operates. In the past, we were passive receivers of information. Because of the way mass communications are structured, we’ve had to be shunted into giant demographic bins, and as a result, our feelings of isolation have increased.

The trajectory we’re following is a little terrifying if we just look at mass media as an indicator of cultural health—one could devote an entire book alone to the specter of reality television and the psychology behind all those tryouts.23

But sneaking up to save us from that blight are social networks: Sharing our authentic selves, versus projecting some spectacle of ourselves, holds opportunities to explore each other’s identities, and thus gain a greater understanding of our needs and values. Through authenticity, we experience understanding, and we create the empathy needed to maintain a healthy social network ecosystem.

Looking back, we’ve been dealing with a sense of increasing isolation over the past century, in part due to the (largely white) flight from cities to the suburbs, and in part due to how mass media have treated us as faceless consumers of product. We’re deluged with mass messages—we’re exposed to about 2,000 pieces of advertising per day. One way out of the cacophony of mass media is to figure out a way to be recognized. But recognition is pretty limited in our culture; one of the few avenues is to become famous. Michael Wesch, a professor of anthropology at Kansas State University, talked about the cultural isolation of the last century in an address delivered at the 2009 Personal Democracy Forum conference (I highly recommend watching the online video). “When the conversations of the culture are happening on television, it’s a one-way conversation. You have to be on TV to have a voice, you have to be on TV to be significant,” he said.24 Before the reality TV craze, most of us couldn’t achieve fame without large amounts of luck and talent. Reality TV changed all that. Suddenly we could become famous just by showing up. It didn’t matter that we’d make fools of ourselves; we’d be recognized, and thus valued . . . even if only for 15 minutes or less.

The onslaught of social media started to move people away from broadcasting inauthentic experiences, led first by the blogging crowd. Blogs are often associated with electoral and advocacy politics, but in practice, the blogging community is much larger and more diverse. Many bloggers are pure diarists, keeping logs of their daily lives and experiences. The rise of other types of social media services that enabled people to contribute short status updates exponentially added to this grand logging experiment. The collective process of posting status updates, pictures, video, blog entries, reviews, and recommendations is called lifestreaming.

There are two sides to the lifestreaming coin: the narcissistic and the self-defining. Narcissism is the easy road: Look at me, look at what I do, look how deserving I am of this attention—and I don’t care what anyone else thinks. The best example of narcissism can be found in the lengths that people go to in reality TV. It’s not just money they’re after. It’s also the huge amount of attention being showered on them. Their inauthenticity is palpable, and their contribution toward cultural and social advancement is low. We experience these people on social networks as well—remember those bad social capitalists from earlier in the chapter, who only broadcast and don’t share?

The flip side of this coin is the movement toward using social network tools to engage in a process of self-definition. We’re all searching for recognition in our culture, but rather than using spectacle to validate our existence, we can use our relationships, and the trust we build as a result of sharing, to pursue this path of self-exploration. We can’t find that on our own; we need each other to evaluate our experiences and then validate our identities. Canadian philosopher Charles Taylor agrees that the search for one’s self can’t happen in isolation.25 Even hermits who run off to the mountains are in some sort of conversation—with God, with their “inner self,” with nature, or with whomever/whatever. Humans need to be in dialogue. “We are expected to develop our own opinions, outlook, stances to things, to a considerable degree through solitary reflection,” says Taylor. “But this is not how things work with important issues. . . . We define this always in dialogue with, sometimes in struggle against, the identities [those around us] want to recognize in us.” Sharing on social networks can be of great assistance in the search for ourselves, because so much of what happens there is dialogue. What you share with others creates the space where conversation can happen; and your experiences, as you use the tools to explore your identity, can start to effect change.

Remember how we discussed the fact that a big part of our social capital is reputation and our contributions to the gift economy? People who share information and answer questions, who create connections of empathy and trust, all while building their own social capital, offer the greatest potential to shift our culture away from the pending implosion of narcissism and apathy that mass communications have created.

Our ability to use social networks and media—by reaching inside for understanding and reaching out beyond oneself to interact with purpose—can help us to lay out the building blocks for change. But there are still barriers to the utopian super-fun happy land of the Internet. Your presence is required, but so is your willingness to take risks to break down those roadblocks.