Steel Trade Flows and Trade Disputes

Steel along with agriculture were the two industries most frequently afflicted by trade disputes in the postwar global trading system of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT). Business news in the 1970s and 1980s was dominated by trade conflicts between U.S. Steel producers and Japan. Disputes with Europe were also common.

Why do steel trade conflicts get so much air time and drama?

Steel has been and remains a very cyclical industry. It makes an intermediate product. Therefore, decisions of others impacting things such as auto demand or decisions on capital investment in construction hugely affect the net demand for steel. These normal business cycle factors have in the past, however, been accentuated by movements in steel trade that can suddenly bankrupt billion dollar companies and throw thousands of workers on the street. Downturns in the economy have often been accompanied by dumping of imports, further depressing steel prices to destructive levels and wreaking havoc with capacity utilization, viable pricing, and layoffs. Dumped products and wild swings in trade flows can quickly turn the finances of capital-intensive industries like steel upside down.

There is some recent evidence to indicate that the globalization of steel has had a dampening impact on these destructive tendencies, that is, the Eastern European operations of a global steel company will not be allowed to put its North American operations into bankruptcy by dumping. However, there continue to be ongoing steel trade disputes, not least because of a slowing global economy.

The chapter begins by getting a base line for trade disputes—what is dumping? We then look at the changing economic geography of the global industry to gain a perspective on steel trade flows. The next section looks at steel trade issues and the Great Recession. The place of China, the elephant in the room, is then discussed. The chapter concludes with a discussion of steel and the state, that is, how governments are still playing a major role in how capital decisions and ultimately how steel trade flows unfold in the world economy.

Dumping: What It Is, Why People Do It

The epicenter of steel trade disputes, particularly dumping cases, has been the International Trade Commission (ITC) in Washington. It is important to understand that the ITC is a domestic, not an international agency. However, US legal definitions and policy decisions rebound around the global steel industry.

Under the provisions of the US Antidumping Act of 1921, the primary definition of dumping was export sales at a price below that of sales in the home market. Economists generally adhered to this criterion, defining dumping as price discrimination between national markets and explaining it with familiar theories of monopolistic behavior. However, the 1921 Act also included a provision to be invoked in the absence of comparable sales data for foreign markets. In such instances, dumping was said to occur when export prices failed to cover a statutory measure of foreign producers’ production costs.1

Beyond the legal definition, there is the underlying question of why people do it if it means they are selling below costs. Sometimes it is because they are trying to force entry into a new market and establish a long-term position. In times of economic downturns, they are trying to keep minimum production running in order to cover base costs of operations. Particularly in emerging countries, there is pressure to earn foreign currency to be used for other purposes.

The 1974 US Trade Act and 1979 Trade Agreements Act further broadened the applicability of these constructed value provisions. As dumping allegations increasingly have come to revolve around the relation of prices to production costs, the issues have extended beyond reasons for price discrimination to encompass also the motivation for sales at prices that fail to cover costs.

The avowed purpose of the 1921 Act was to deter predatory pricing in international trade in order to prevent foreign monopolization of domestic markets. Its provisions, as incorporated into the 1930 Tariff, remained little changed until the 1950s. The Secretary of the Treasury was to investigate dumping complaints by comparing US import prices with the “fair value” of imports. On finding that fair value exceeded US import prices, Treasury was to calculate the difference, known as the dumping margin. Subsequently and with a different methodology, if there was evidence supporting a finding of material injury to US producers then Treasury was empowered to assess an antidumping duty. Measurement of US import prices was straightforward: the FOB factory sales price could be used except when the transaction between foreign supplier and US purchaser was not at arm’s length, in which case the US market price, net of import charges and costs of transportation and preparation for the market, could be substituted.

From the law’s inception, the calculation of fair value was ambiguous, since the concept was not defined by statute. From 1921 to 1954, Treasury used as a standard for fair value a commodity’s foreign market value or, in its absence, constructed value. Foreign market value was a transaction price, preferably observed in the exporter’s home market but otherwise in third markets.

Constructed value was a complex measure made up of allowances for production costs, costs of preparing the good for shipment, and statutory minima for general expenses and profits. Before 1955, Treasury calculations of fair value and foreign market value rarely proved problematic. Most dumping cases simply were disposed of on the grounds that injury was absent or on the acceptance of price assurances. In 1954, however, an amendment to the Antidumping Act assigned responsibility for determining injury to the Tariff Commission and instructed that injury decisions be deferred pending the Treasury ruling that dumping was present, thereby subjecting the Treasury decision to public scrutiny. Repeatedly, Treasury was forced to revise its procedures as new complications arose. On several occasions between 1958 and 1974, antidumping regulations were modified to bring them into conformance with established practice.

The amendments to the Antidumping Act contained in the Trade Act of 1974 concluded this process of revision. Of greatest consequence was Section 205(b), which defined new circumstances under which the constructed value criterion could be substituted for foreign market value. In instances where sales “over an extended period of time and in substantial quantities” were made in the foreign producer’s home market at prices below costs of production, those foreign market prices were to be disregarded and constructed value calculations were to be substituted. In spite of ambiguity about the meaning of “an extended period” and “substantial quantities,” this revision of the law represented a significant shift in the design of US antidumping policies from an emphasis on dumping as price discrimination to an emphasis on dumping as sales below cost.

In the 1980s and 1990s, the majority of steel trade cases by US producers were upheld regarding dumping and injury findings. Though, for all the reasons discussed in prior chapters, this did not prevent the painful restructuring of the industry. The related issues of government subsidies that distort trade flows were significantly eased by the introduction of a clearer and more accepted definition of what constituted a subsidy. But there remains a steady stream of dumping allegations.

On the injury side, we may be in the midst of a policy shift. Negative determinations by the ITC on injury determinations are relatively rare. However, three recent ITC cases rejected claims that steel product imports were hurting the US industry: steel wheels from China, refrigerators from Mexico, and galvanized wire from Mexico and China. A majority of cases that get to final determination are affirmative. The recent cases may amount to a game changer. It may cause domestic producers to think twice about making such filings. The expense of filing cases and uncertainty over outcomes raise the stakes for potential litigants. If you file and lose, it is a big loss in legal costs, management time and a significant loss for the market position of the industry.

The Economic Geography of Global Steel

Understanding the shifting economic geography of steel is critical for gaining a perspective on the emerging global industry, including its relevance to steel trade issues. Where are the major producers located, what are the balances and imbalances of demand and supply, what is the balance of trade, and what are the dynamics of growth?

To repeat, it is important to understand that while there are global companies there is not one global market in steel. There are three key regional markets: North America, Europe, and Asia.

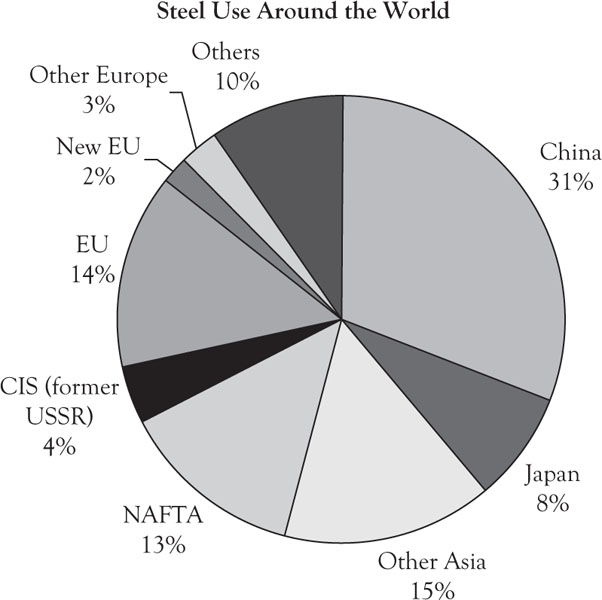

At first glance the global steel industry appears to be in approximate balance between production and consumption.

The big markets of NAFTA, the European Union, and even China seem to be reasonably well balanced in terms of demand (consumption) and supply (production).

However, as in many things, the devil is in the detail. The macro

economic view does not readily disclose the subtleties of market dynamics and the underlying tensions in steel trade and global production flows.

Key Regional Markets

As mentioned above, there are three key regional markets in global steel: North America, Europe, and Asia. The numbers should be considered against a total world capacity of 1,351 millions of tons as of 2010.

Ten Largest Steel-Producing Countries (Millions Tons)

|

Rank |

Country |

Steel production |

|

1 |

China |

626.7 |

|

2 |

Japan |

109.6 |

|

3 |

USA |

80.6 |

|

4 |

Russia |

67.0 |

|

5 |

India |

66.8 |

|

6 |

South Korea |

58.5 |

|

7 |

Germany |

43.8 |

|

8 |

Ukraine |

33.6 |

|

9 |

Brazil |

32.8 |

|

10 |

Turkey |

29.0 |

China is a story unto itself. The remaining key markets of Asia, Europe, and North America are roughly comparable in size.

Steel Trade Balances

There is a fundamental asymmetry in global steel markets. Similar to the auto industry, there is a North American market that has significantly more imports than exports and an Asian market with significantly greater exports than imports, led by Japan and China.

Steel Trade Balances (2010 Million Tons)

|

Region |

Exports |

Imports |

Net trade balance (imports–exports) |

|

North America |

24,163 |

40,238 |

-16,075 |

|

European Union |

134,633 |

125,115 |

+9,518 |

|

Asia |

132,325 |

114,235 |

+18,090 |

|

China |

41,646 |

17,181 |

+24,465 |

|

Japan |

42,735 |

4,440 |

+38,295 |

The trade imbalance in North America has other serious implications. If we even take the high-end productivity goal of steel companies at 1200–1500 tons shipped per employee per year, then this translates into about 15,000 jobs missing. With the standard multiplier effect for steel of 6×, then nearly 100,000 jobs are missing in North America compared with what the employment situation would be if there was balanced trade in steel. That is an employment outcome that would change people’s perception of the importance and future of the industry among other things.

Steel and the Great Recession

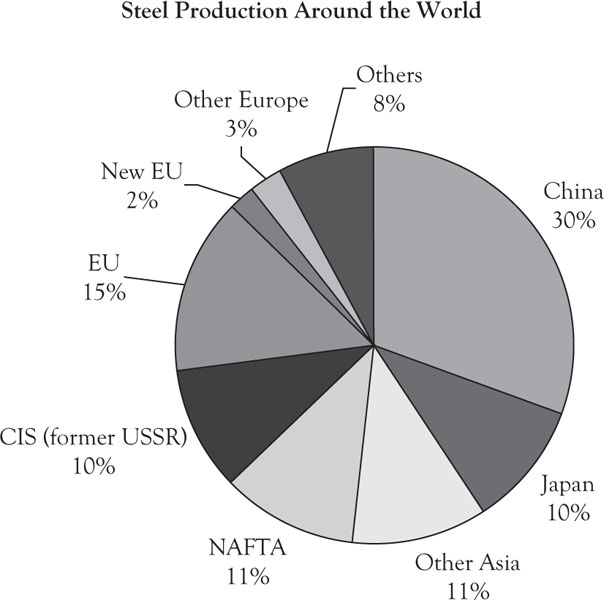

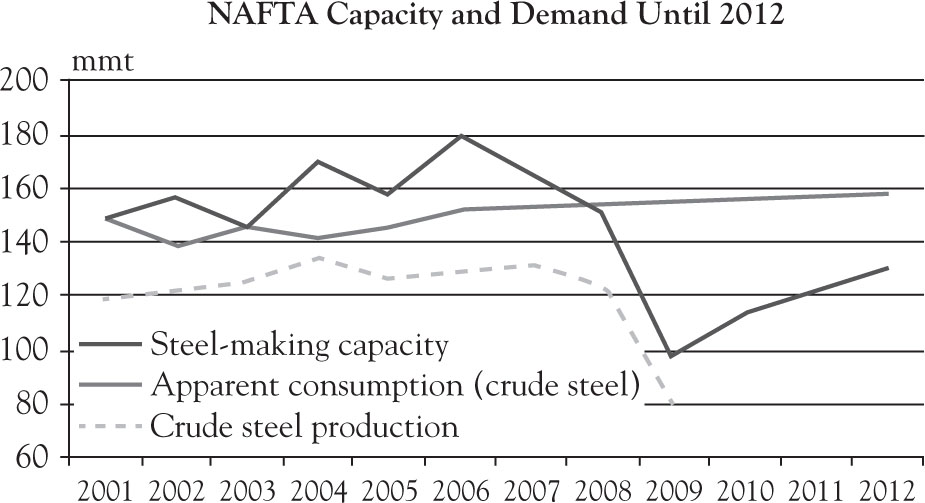

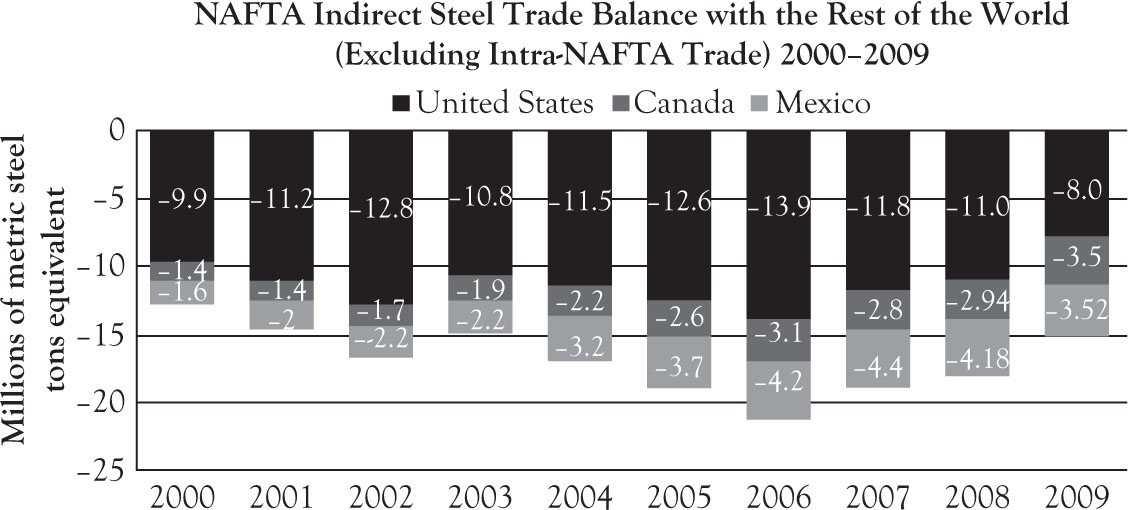

As a result of the global economic crisis, NAFTA steel production declines in 2009 were larger than those in other regions of the world.

As a result, the NAFTA Steel Trade Balance with the rest of the world (ROW) going forward is in a fundamentally different situation. The steel balance in the region has shifted from one where it was historically steel short (requiring imports), to one where it now has capacity to increase production for domestic and export consumption, without the need for imports. Given the anticipated postcrisis steel consumption growth in NAFTA and ROW, this is a significant opportunity for NAFTA steel producers.

Steel Trade Disputes

As background to understanding trade disputes, certain structural features of the steel industry can have a significant influence on trade flows. Steel making is capital intensive and involves relatively high fixed costs. Consequently, there is an incentive for producers with significant excess capacity to increase production to spread fixed costs over a greater volume of production. However, there is a countervailing incentive to align production with demand in a steel maker’s domestic market. Excess supply in the “home market” can result in pricing instability, which can negatively impact returns.

International trade agreements are also important. The emergence of the NAFTA steel market has resulted in a situation where the home market for steel makers in the region is the NAFTA market. However, global excess capacity and the emergence of China and other countries as major steel exporters introduced significant challenges for steel makers here.

The combined effect of global overcapacity and the incentive to maintain high production levels creates an incentive for steel makers located in markets with significant excess capacity to increase production for export markets. This allows steel makers to act in a manner that promotes pricing stability in the home market while increasing capacity utilization by selling into export markets.

This situation may be further exacerbated in situations where governments adopt policies that influence production decisions and/or confer production or export subsidies on steel products.

The combination of overcapacity and government involvement has resulted in widespread dumping and subsidization of steel products on export markets.

Over the past decade China has emerged as a major driver of international trade disputes. For example, since joining the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001, Chinese government measures affecting a wide variety of industries have been challenged before the WTO. Other WTO members have brought challenges against measures affecting auto parts, financial services, intellectual property, taxation, and technology products.

The lengthy list of Chinese steel products found to have been dumped and/or subsidized in export markets illustrates that the structural features of the steel industry combined with government influence and support have resulted in a pattern of dumping and subsidization in export markets.

Most recently, the United States, Mexico, and the European Community have initiated WTO dispute settlement proceedings regarding the Chinese government’s system of export restraints affecting raw materials. Canada is an active third-party participant to the proceedings. It is alleged that China maintains a system that restrains exports of raw material inputs used in the production of finished goods such as steel. The export restraints are alleged to raise world prices while lowering Chinese domestic prices for key steelmaking inputs such as coke.2

The Effects of Dumping in the Domestic Market

Unfair trade practices are often the result of asymmetric market access and economic distortions in the exporter’s home market. Dumping and subsidization cause negative economic and social consequences on affected communities.

Duties Imposed on Chinese Steel Products

|

Product |

Canada |

United States3 |

Mexico4 |

|||

|

Dumped |

Subsidized |

Dumped |

Subsidized |

Dumped |

Subsidized |

|

|

Hot-rolled sheet |

X |

X |

||||

|

Plate |

X |

X |

X |

|||

|

OCTG |

X |

X |

||||

|

Seamless OCTG |

X |

X |

||||

|

Standard pipe |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||

|

Carbon steel butt-weld pipe fittings |

X |

|||||

|

Drill pipe |

X |

X |

||||

|

Steel concrete reinforcing bar |

X |

|||||

|

Steel nails |

X |

X |

||||

|

Light-walled rectangular pipe and tube |

X |

X |

||||

|

Steel wire garment hangers |

X |

|||||

|

Circular welded carbon quality steel line pipe |

X |

X |

||||

|

Circular welded austenitic stainless pressure pipe |

X |

X |

||||

|

Steel threaded rod |

X |

|||||

|

Welded steel chains |

X |

|||||

|

Welded carbon steel pipe |

X |

|||||

|

Seamless Steel Pipe |

X |

|||||

|

Steel bolts |

X |

|||||

|

Steel valves |

X |

|||||

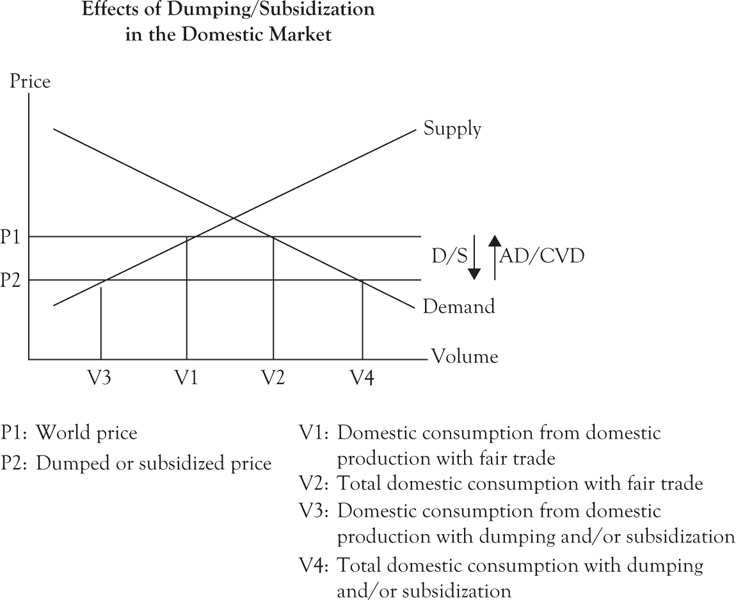

The existence of nonmarket influences and government support of the Chinese steel industry serve to increase Chinese exports and cause distortions in the importing country market. The economic consequences of dumping or subsidization from the importing country’s perspective are illustrated in the following graph.

Government support and other structural factors allow exporters to lower their selling price from the world price (P1) to the dumped and/or subsidized price (P2). The impact on domestic producers in the importing country is decreased volumes sold in the home market (domestic share drops from V1 to V3). Exports at unfairly traded prices experience a corresponding increase (V2 to V4). D/S stands for dumped or subsidized prices. ADV is ad valorem duties applied.

Trade laws minimize the disruptive economic and social effects that unfairly priced imports have on established communities by restoring market equilibrium.5 The imposition of antidumping and/or countervailing duties on dumped or subsidized exports restore production to undistorted levels by offsetting the effects of the dumping and/or subsidization.

Trade Liberalization

The negotiation of trade agreements involves the balancing of concessions and opportunities by the parties to the agreement. In principle, each agreement should be assessed to determine whether, as a result of a given agreement, the industry is better off than it would be without the agreement. The existence of effective trade remedy laws contributes to trade liberalization by providing a mechanism to address specific concerns about the potential negative effects of unfair trade, while allowing for broader trade liberalization.

From a trade policy perspective, trade liberalizing agreements should increase the overall size of the market available to domestic producers. This involves an assessment of the access granted to the domestic market in exchange for improved or expanded access for domestic producers in export markets. Providing trading partners with expanded opportunities in the local market is one-half of the equation. The net benefit of a given agreement can only be understood by examining whether the increased access offered to the domestic market also affords local producers with an equivalent or greater opportunity in export markets.

As noted above, the NAFTA market has shifted to a steel “long” situation, which means that producers in the NAFTA countries have the ability to serve the needs of the NAFTA market as well as export markets.

The view of the industry is that to maintain a steel balance in the NAFTA region, there must be a public policy commitment to restore North American manufacturing as a foundation for economic growth and sustainable employment. They view China as in effect pursuing a mercantilist policy in violation of the content and spirit of the international trade rule regime. Furthermore, they warn about the risk that inequitable application of climate change policies will allow those with little to no regulatory burdens to in effect, engage in environmental steel dumping. The latter would both be trade-distorting and also prejudice the environmental and sustainable development objectives that the NAFTA steel producers themselves endorse.

The Impact of China

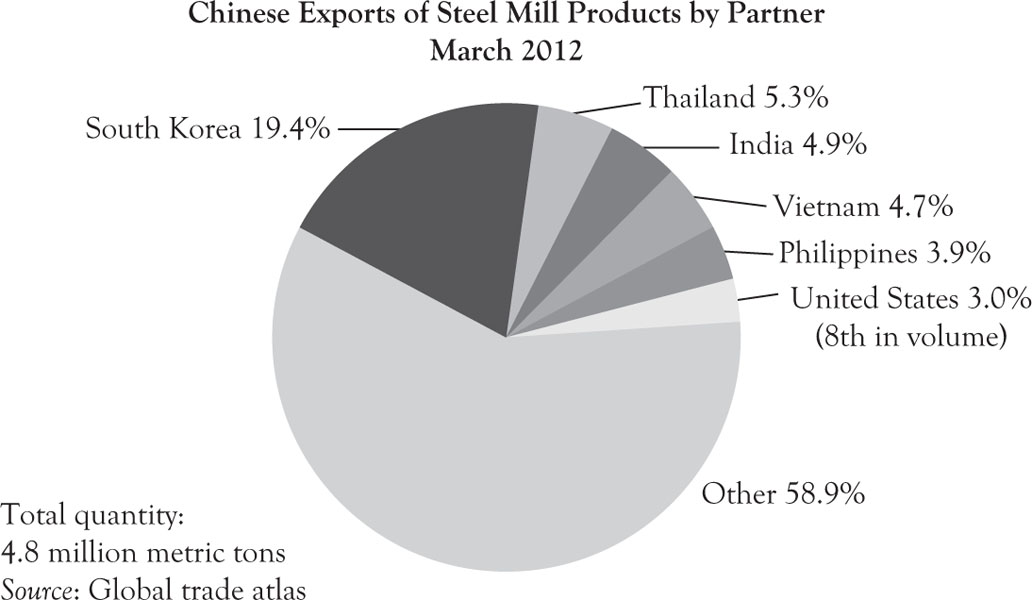

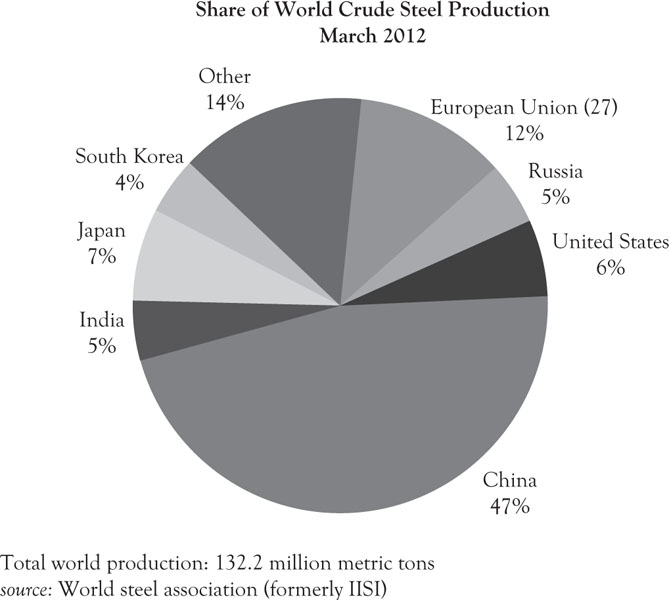

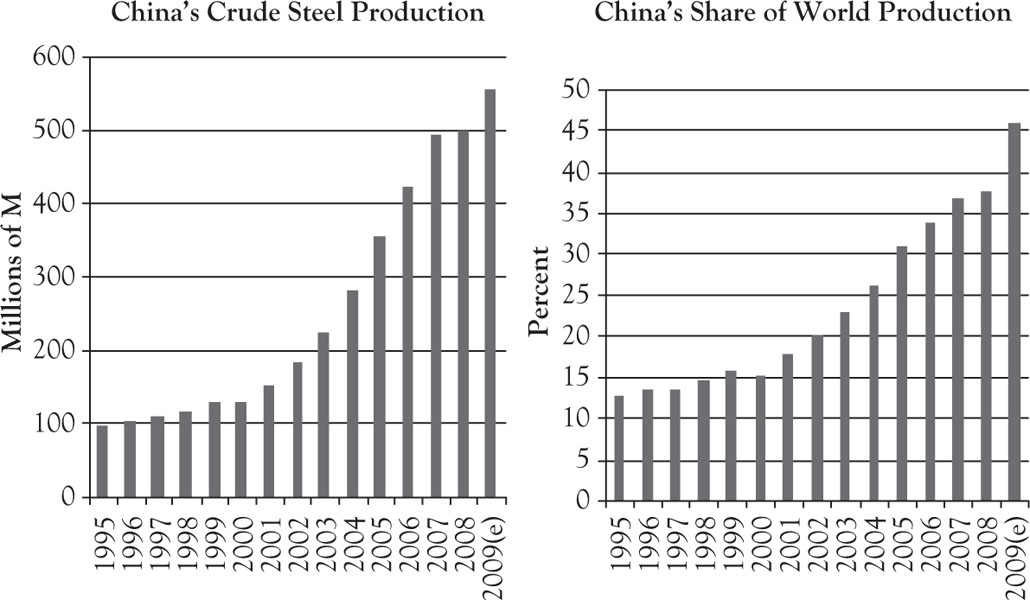

The huge expansion of Chinese steel capacity has raised concerns about the potential of dumping and a flood of Chinese imports. The current facts are that Chinese steel exports are a rather small amount of total production, about 4%. However, the sheer size of the Chinese industry, approaching 800 M tons, can still mean serious tonnages on the order of 40–50 MTs or more are available for export. Therefore, it matters a lot where these Chinese exports are going. The graphs present some of the most recent relevant data points.

Source: Department of Commerce. International Trade Administration. May 2012.

Source: Department of Commerce. International Trade Administration. May 2012.

It may come as a surprise to many that most Chinese steel exports are going into the Asian market. For instance, China sends eight times the amount of steel to South Korea that it does to the USA. However, there are complex dynamics concerning China’s presence in the Asian regional market. Japanese steel producers are increasingly concerned about shipments coming in from China, or even more that shipments to South Korea will result in the latter producers shipping to Japan in a second bounce effect.

The challenge for producers and policy makers is China’s potential to directly upset this equilibrium through non-market-based behaviors. In addition, there is the problem of indirect trade in steel because of China’s presence in manufacturing and further displacement of NAFTA manufacturing capacity.

China now represents almost half of global steel production. In the past 10 years, it has increased its crude steel production by over 400 MTs, and increased its share of world production from 15% to almost 50%.

Source: World Steel Dynamics, Inside Track #77 (May 30, 2007), World Steel Dynamics, Truth & Consequences #44 (Nov. 15, 2007); World Steel Dynamics, Inside Track #87

(June 12, 2008); World Steel Dynamics, Truth & Consequences #50 (Feb. 9, 2009); World Steel Dynamics, Inside Trade #97 (Oct 2, 2009).

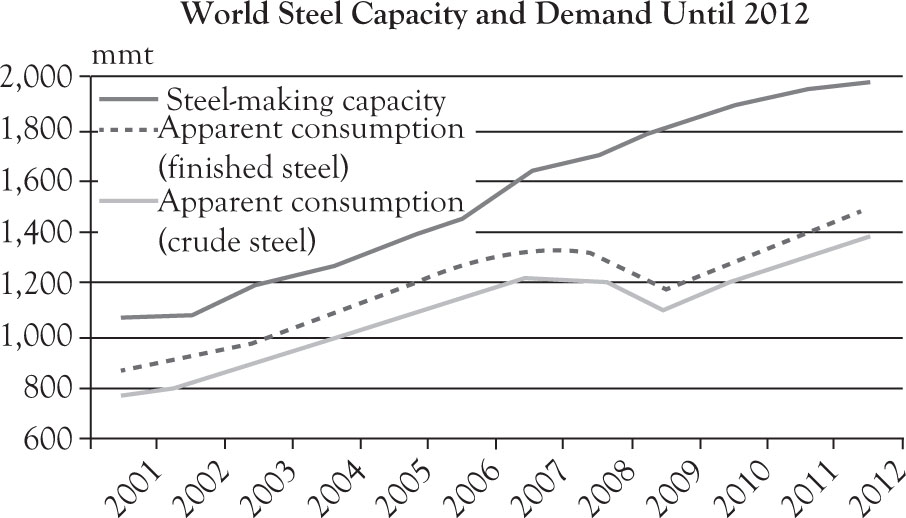

The best source of data and forecasts for global steel come from the OECD Steel Committee in Paris. Their most recent Steel Outlook is from December 2009.

The OECD sees world trade as recovering over the next three years, led by the major non-OECD countries of the BRIC. Their projections suggest that world steelmaking capacity would rise from 1,806 million tons in 2009 to 1,986 million tons in 2012. World steel demand is expected to rebound in 2010, and grow by 6–7% per annum in 2011–2012 to reach a level near 1,500 million tons by the end of the period.

While there is uncertainty surrounding the outlook, it appears that the gap between world capacity and demand, which averaged approximately 216 million tons during 2000–2007, will widen to over 500 MTs. Such an overhang presents significant structural challenges to the industry. It raises questions about how the industry adjusts and what government policies might help manage the situation.

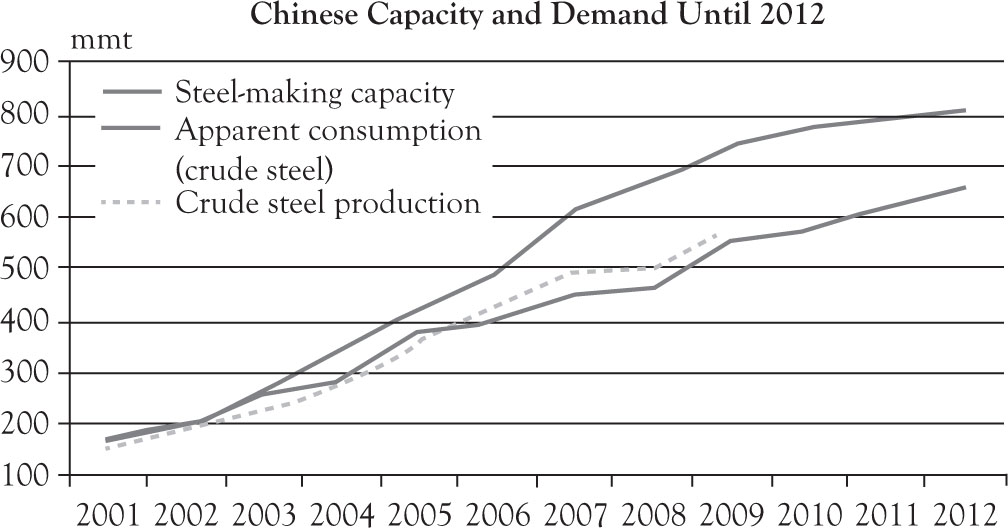

In the critical case of China, the OECD observes that capacity growth outstripped demand growth from 2002 to 2007 and it turned into a large exporter of steel in the latter part of that time period. By 2012, based on the OECD forecast, China will still have an excess of capacity in the range of 150 MTs, or approximately two times the size of the entire American steel industry.

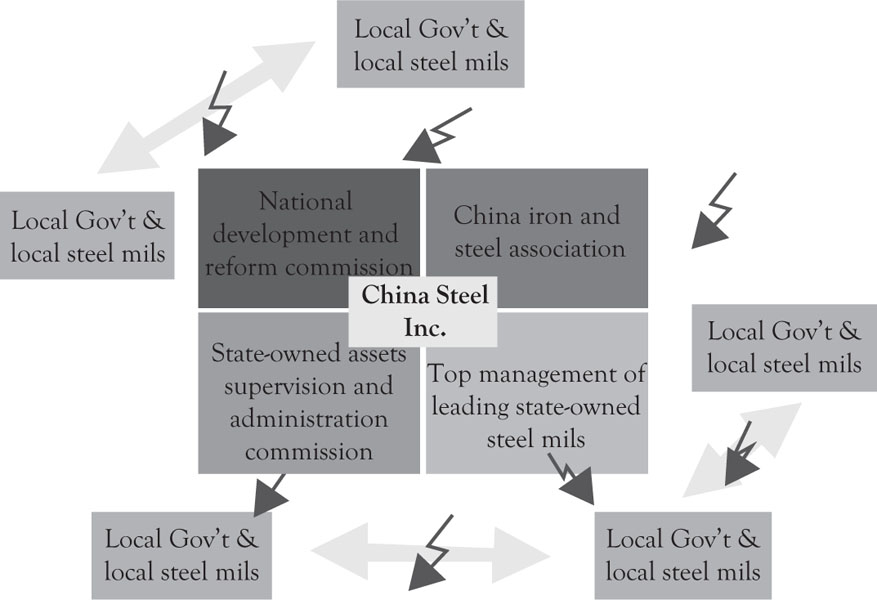

Global steel companies are unanimous in the view that China’s steel industry is firmly embedded in a powerful state–business nexus. Chinese steel companies are not operating in competition based on the domestic market environment, but rather hold very close relations to government agencies on local, provincial, as well as central levels. Except for two enterprises, their top 20 steel corporations are state-owned on a majority basis. In sum, China is a nonmarket economy in steel. Its steel industry, a multilayered system of politico-business alliances can be summarized in the following schematic:

Chinese governments support their steel enterprises through a National Steel Policy and provincial/local actions. The broad array of mechanisms includes currency/capital market interventions, direct and indirect ownership, subsidies, quotas, import/export taxes/rebates, export targets, etc. Government intervention is provided across the entire supply chain, including energy, raw materials, steel, manufactured products, and more. The interventions are structured to artificially and selectively increase the competitiveness of Chinese goods, while concurrently increasing costs and decreasing relative competitiveness of other global players. China is no longer just a supplier of lower added-value steel products; instead, it has shifted to export more higher value-added materials encouraged by government.

Source: Report prepared by THINK!DESK China Research & Consulting for EUROFER—the European Confederation of Iron and Steel Industries. January 2009.

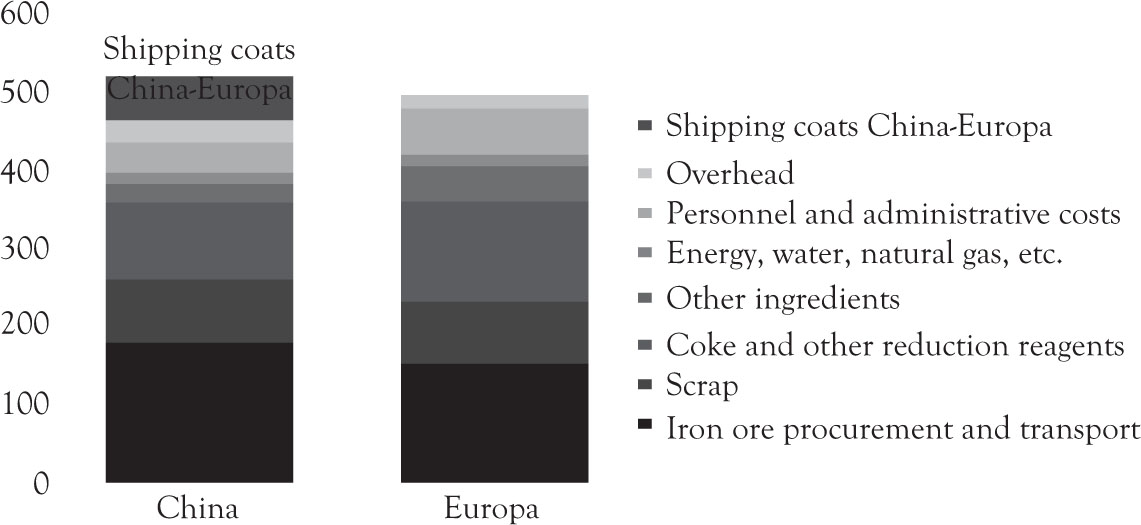

For an outsider’s viewpoint, the steel situation is strange as China lacks many natural advantages for steelmaking. China must import significant amounts of quality raw materials, at world prices, which represents the majority of their total production costs. Growth of coal-fired plants, limited supply of steel scrap, and less efficient and environmentally challenged mills reduces their competitive balance. The availability of cheap labor does not offset their real cost disadvantage, as steelmaking generally now requires less than 2 hours of labor per ton.

As a result, Chinese steel exports to NAFTA and to the European Union actually incur higher costs than those that arise for local producers supplying the local market. Netting out subsidies and the impact of government market interventions would prove the real ‘market-based’ cost structure of Chinese steel production to be substantially higher than officially reported numbers.

Comparative Steel Production Costs: China versus EU

Source: Report prepared by THINK!DESK China Research & Consulting for EUROFER—the European Confederation of Iron and Steel Industries. January 2009.

Nobel Prize-winning economist Paul Krugman has recently said that global economic growth would be about 1.5 percentage points higher if China stopped restraining the value of its currency and running trade surpluses. He says that China’s currency policy has a “depressing effect” on economic growth in the US, Europe, and Japan, as measured by gross domestic product. If China’s currency, the yuan, were not undervalued, it would have a “significant” impact on the global recovery.

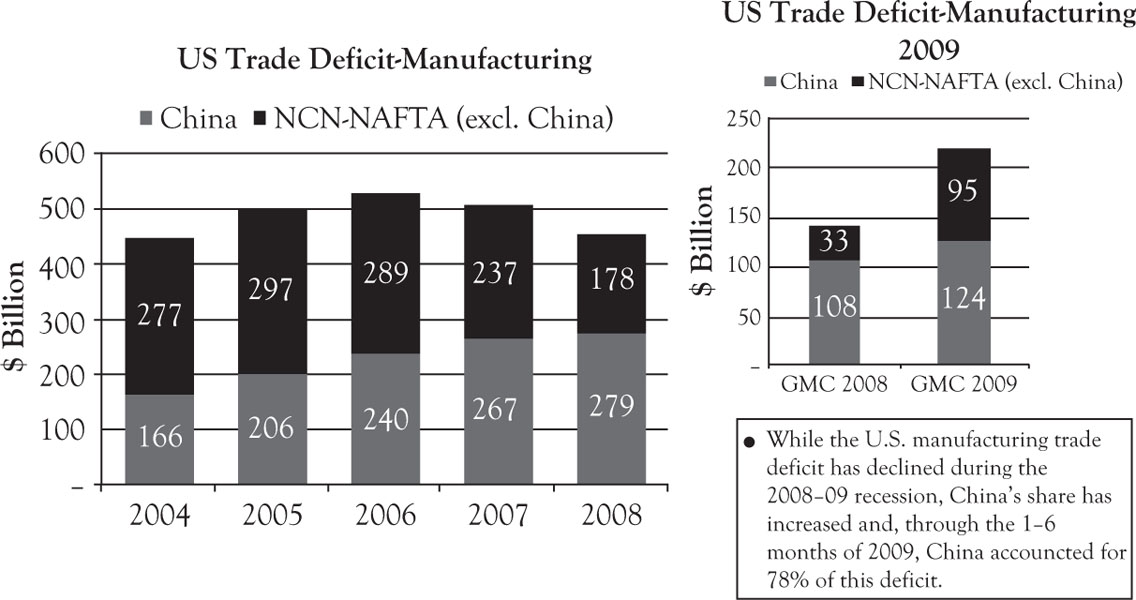

China also has a significant impact on manufacturing trade deficits and indirect steel trade deficits.

For steel in particular, the indirect steel deficit trade remains a major source of concern.

The question of China’s role is a preoccupation for steel companies around the world. The crunch point may come in the next two years. China’s steel consumption is expected to peak at 750 MTs in 2014. At that point, there will be serious overcapacity in their industry and a restructuring scenario emerges. Will this excess capacity be put out into the world markets in the form of an export surge? The Chinese government opposes this and has taken some actions to restrict it happening. If this remains the case, we will witness another surprise in steel development in China—a painful process of industry restructuring.

Global Steel, the State, and Trade Flows

The steel industry, as discussed previously, has been globally consolidated to an unprecedented degree. One of the expected benefits of the consolidation was the dampening down of some of the key drivers of disruptive steel exports and dumping. Private corporate interests take precedence over nationalistic and mercantile agendas. As this book is being written in mid-2012 the evidence for a more benign era of international steel trade flows is at best mixed. During the recession, imports lagged but there are renewed fears that as things gradually improve, while China slows, there is a risk of a renewed import surge.

The general challenge of trade and its relationship to capital flows can be crystalized in the dilemma facing the largest steel company in the world. The biggest player in the industry, ArcelorMittal, is at the center of this strategic story. It has been the lead consolidator internationally and it could reasonably be expected that, for instance, Arcelor Ukraine would not be allowed to put Arcelor USA out of business. Facilities would reduce production levels rather than dump product abroad.

In the immediate aftermath of the Financial Crisis, 2008–2009, there was some evidence for this policy thesis. The steep reductions in steel production and capacity utilization levels were not matched with as steep declines in market prices.

However, there was an upside to the positive expectations of consolidation. As the economy turned around, it was expected that companies could increase prices to catch the upward movement of the business cycle. However, the evidence of 2011–2012 does not match expectations. Steel companies tried to increase prices substantially, led by Arcelor, but these have not proved to be sustainable. Renewed import concerns and trade cases have re-emerged during the current slow recovery.

Trade Policy and Competition Policy

Inevitably Intersect

One of the puzzles about the steel industry is the issue of steel being a big industry at the national level, but a borderline player at the global level. Part of the answer to the puzzle is that steel, largely because of the weight of the product and the scale of efficient production, is produced largely, be it by integrated or by EAF producer, for regional markets. A large part of this in turn is because of manufacturing being oriented to geographic clusters.6 It is these regional concentrations of the customer base that largely dictates the configuration of steel producers.

Meanwhile, the concentration in ownership in iron ore and coal producers is an outlier in the global economy and probably will undergo antitrust and other commercial law challenges in the coming years. European antitrust authorities are already seized of the issue.

The conclusion is that there will, for the foreseeable future, be a global steel market that is very much regionalized. It will, however, be brought into better balance through a combination of corporate, legal, and public policy motivations. In steel, as in auto, the North American market continues to be unique in its imbalance of imports and exports compared with both Europe and Asia.

Nation states are still important in steel. Among other things it impacts the evolution of steel industries, particularly in Asia. It is even a major challenge for the largest steel company in the world, ArcelorMittal.

Steel and the State was a common point of discussion in policy debates and the academic literature 25 years ago. The issues of protectionism and dumping, public subsidies, and excess capacity issues were common questions in the media and trade regulatory decisions. In fact, in the later 1980s, a majority of steel capacity around the world had direct and indirect government ownership and subsidization writ large. Much of the liberalization of steel economics in the 1990s and carrying into this century was about the wind down of public ownership in steel and a major reduction of trade-distorting subsidies. The consolidation wave in steel in the past decade has been very much a case of the takeover of formerly public steel assets by private steel companies. This was key to the emergence of ArcelorMittal but as well of the new presence of U.S. Steel in Eastern Europe.

Raising the issue of steel and the state here is not to go over that old ground one more time. It is to raise a current significant issue of steel and the state in the new environment of globalized steel. It is possible to say broadly that a major strategy of the new global steel companies is to be present in all key markets, particularly those of North America, Europe, and Asia. However, to implement that strategy requires access to those markets. The elephant in the room is the government of China, which will not allow majority foreign ownership of steel assets. For a comparison, one can see the importance of the role(s) of the state by considering how the global auto industry’s expansion into Eastern Europe is so fundamentally different from the emerging auto industry in China. This anomaly is evident even to editorialists in the Financial Times of London. The challenge for global steel companies in implementing a truly global strategy has been well identified recently by their description of the strategic dilemma facing ArcelorMittal.

Sometimes a company prays for a strong Chinese economy not so that it can sell more products to China, but so that the country will sell fewer products to the world. Take ArcelorMittal. Its revenues rose by 20% last year to $94bn, and its crude steel output edged up to 91.9m tons. The distance separating ArcelorMittal, the world’s largest steelmaker, from second-placed Hebei Iron & Steel of China is impressive.

There is, however, a twist. ArcelorMittal’s founder Lakshmi Mittal puts a brave face on matters, but the truth is that his company produces and sells little steel in China. Beijing refuses to let foreign steelmakers take majority stakes in large Chinese companies, so ArcelorMittal, which only makes about 7% of its steel in China, must rest content with two modest joint ventures.

For ArcelorMittal, which produces about 6% of the world’s steel, such trends are troubling. It is desperate to protect its global market share without suffering the price pressures that might emerge as a result of fast increasing Chinese production. Yet its Chinese rivals need to sell their steel somewhere.

The best hope is that China records buoyant economic growth this year. In principle, this would absorb much of the extra domestic steel output and, as a happy side effect and curb the appetite of Chinese companies to seize world market share from ArcelorMittal. Not for nothing is ArcelorMittal counting on 8% growth in China in 2012.

In Europe, the steel story is different but familiar to anyone who knows the auto sector story: structural overcapacity in the industry, and a backdrop of low long-term economic growth.

The Financial Times7 has stated the strategic dilemma for ArcelorMittal. Mr. Mittal became famous as the businessman who defied the received wisdom of the 1990s that steel was an industry on which the sun was setting after 150 years. By creating a group that now employs 260,000 people in more than 60 countries, Mittal showed how to make healthy profits out of steel.

But ArcelorMittal is aware that European steel demand is unlikely to return for the foreseeable future to the levels seen before the 2008 financial crisis. With European plants accounting for about 40% of his company’s output, this leaves Mr. Mittal with little choice but to reduce operations.

The process is already in motion. The closure in October of two blast furnaces in Belgium was the first such action since the company’s 2006 creation out of the €26.9bn merger of Mittal Steel and Arcelor. Elsewhere, mills are idle in Spain and a voluntary redundancy scheme is being implemented at a Czech plant.

However, none of these actions gets to the heart of ArcelorMittal’s strategic problem. The 2006 merger was founded on the twin assumptions of an Asian hunger for steel, which the company could feed for decades to come, and a resilient European market primed for its high-tech products. The strategy was and is not completely misplaced. But it has suffered a blow from Europe’s debt crisis, which has dramatically reduced demand for cars, construction, and other steel-buying sectors. At $10.1B, the company’s earnings before interest, tax, depreciation, and amortization last year were less than half those of 2008. The steep decline over the past three years in ArcelorMittal’s share price was all but unavoidable.

Blocked in Asia and on the defensive in Europe, ArcelorMittal, the steelmaker par excellence, now styles itself a “steel and mining company.” Iron ore and coal account for less than 10% of its business, but mining is growing fast and makes a tidy profit. The company now has a specialist mining management team and reports its results as a separate segment.

Time will tell if this is a sensible response to ArcelorMittal’s challenges on the steel front. But digging raw materials out of the ground was not exactly what Mr. Mittal had in mind when he executed his famous 2006 merger.

ArcelorMittal is by a large margin the biggest company in the global industry. This huge private corporation still faces its limits in the face of an assertive nation state. Further, it underlines that flows of investment capital are absolutely critical to steel trade flows for the future fortunes of the industry. And, that these flows function well short of the expectations of free markets.