The Frame for Integrity in Managerial Education

The Process of Academic Ethos Management

A university does not simply exist; rather, it happens, becomes, and transforms. For a contemporary company, it is the consciousness and stability of its academic ethos core values that conditions the way it evolves. Empirical studies1 have found that organizations that have survived for a long period of time and outperformed their competitors have a homogeneous and intense identity, which at the same time is complex and abstract enough to survive over time. By discovering and defining academic ethos core values, management makes general statements about the central characteristics (core values) of the university, which in the existing conditions are commonly shared and preferred, shaped by the entrepreneurial attitudes and behaviors of people at the university. They therefore create foundations for the development of social ties among academic community members and build the relationship of loyalty, trust, and cooperation—the necessary conditions for the development of a learning company.2

The key differentiation among higher schools lies not in the general core values statement (many universities have very similar or nearly identical core values) but in the effectiveness of transmitting the chosen academic ethos to the academic community and transferring academic ethos core values (cultural identity) into university behavior.

A particular logic of transferring academic ethos values into an organization’s developmental behavior is the university’s individual paradigm, typical for a given higher school—its cultural identity. The instrumentarium of the cultural identity management of a university is what we call Academic Ethos Management (AEM). Entrepreneurs, founders, and other business leaders used to manage and do manage, consciously (and unconsciously), in an operationalized way, more or less institutionalized, in the form of specific methods (special and intentional sets of managerial actions), the university’s cultural identity to ensure its efficient and effective process of development. In a contemporary university, cultural identity management takes place in a conscious and organized way through AEM,3 so the instrumentarium of academic ethos core values management and its transmission to the members of academic community and other stakeholders is a process of academic ethos management.

On the basis of our previous study,4 we may conclude that academic ethos management is a process of managing university culture identity and transferring the university’s core values from one management generation to another by taking over responsibilities resulting from core values and their protection for the benefit of the organization and its members through their institutionalization (enacting and maintaining) in a morally positive manner. The development of particular phases (stages) of AEM is presented in Table 10.1.

Table 10.1. Characteristics of Academic Ethos Management Phases

|

Academic Ethos Management Phase |

Phase Component |

Characteristics |

|

Discovering and developing core values of academic ethos |

Discover core values of academic ethos |

Values should be discovered by representatives of all groups that constitute an academic community (president, deans, heads of departments, faculty staff, administration staff, students) Values should be identified on: – Individual level – University level The discovered values should be: authentic, shared, constant, few, guaranteeing the flourishing of individuals and a university |

|

Description (definition) of core values |

– The university level – The university’s unit level – The individual level |

|

|

Definition of desired behaviors |

The definition of academic core values, desirable behaviors should concern the whole academic as well as its particular groups like: students, academic teachers, scientists, administration staff, and even for students’ parents or guardians. |

|

|

Definition of unacceptable behaviors |

The definition of unacceptable behaviors should concern the whole academic as well as its particular groups like: students, academic teachers, scientists, administration staff, and even for students’ parents or guardians. |

|

|

Enacting the core values of academic ethos |

Supporting core values of academic ethos in university’s goals, objectives, and measures |

University leaders should communicate to academic community what will be done for core values implementation (goals), how it will be done (objectives), and how the effect of core values implementation will be measured Each core value should be expressed by a university through particular objectives, tasks for its realization, and measures enabling to assess the effectiveness of its activity. |

|

Formalization university’s policies, procedures, and codes |

Involves: – Developing policy statement or goal statement – Developing core values statement – Defining communal responsibilities and rights – Defining academic pledge (general pledge, student pledge, faculty members pledge, and parent pledge) – Description of definitions and consequences of prohibited behaviors – Descriptions of tips to prevent academic misconduct – Description of reporting and adjudication process – Developing procedures of whistleblowers protection – Developing procedures for sanctions and appeals |

|

|

Communicating core values of academic ethos |

The spectrum of communication tools includes: involvement of top management (values modeling), cultural models, declarations of core values language, university traditions reflected in myths, story tales, legends, academic rituals and ceremonies, songs or architecture symbols (monuments, logos), physical symbols (gowns, rings, mascots), or symbols of prestige (presidential costume, chain, mace) University should also use modern technology (social media: Facebook, LinkedIn, Second Life, etc.) and chatterbots for communicating core values of academic ethos. |

|

|

Maintaining core values of academic ethos |

Protecting core values |

Comprises: – Recruitment (cultural adequacy of prospective employees) – Core values explaining with the use, for example, new student conferences, first meeting of every course, new faculty orientation, graduate teaching assistant training, faculty/staff job application materials, handbooks, catalogue, admission application materials, student rules and handbooks, course syllabus, university’s www site, special publications for students act – Cyclic training for both current and new employees equipping with the capabilities to act in compliance with a particular value of academic ethos – Training for students on values of academic ethos: 1. in the classroom by • positive classroom climate, • exemplar pattern of academic teacher’s behavior during classes, • specifying desirable as well as reprehensible behaviors in syllabus, • discussions with students, 2. out of the classroom by: • creating on university’s website a FAQ section concerning values of academic ethos issues, • organizing contests for slogan, poster, T-shirt, or a comic that shows positive behaviors compliant with core values, • organizing movie festivals, symposium, seminars, lectures of scientific personages or discussion panels for students, faculty members, focused on core values of academic ethos. |

|

Controlling and redefining core values of academic ethos |

– Motivating and awarding: Formal and informal rewarding (diplomas, praise, awards), Formal punishments and reporting about reprehensible behaviors. Regular monitoring of core values implementation level through checking compliance between academic community members’ behaviors and the behavioral patterns assigned to core values of academic ethos. Supplementing core value sets or changing their definitions that result from, for example, a merger, changes in the university’s environment, development, the atmosphere of distrust and hostility, cynicism and pessimism inside the university. |

Source: Author’s own study.

The objective of AEM is to establish a university culture of integrity by acquiring a favorable image of university and consequently a positive identity of the university among employees so that, in the long run, this can result in the acquisition of a favorable reputation of the university; this, in turn, leads to members of the academic community displaying positive behavior toward the university.5

Mark Twain once said, “It is curious that physical courage should be so common in the world and moral courage so rare.”6 The development of a university’s cultural identity as well as its effective AEM does not guarantee a higher school to be free from corruption and unethical behavior. Numerous cases of vulgarization of this process are known from managerial practice. Undoubtedly, core values may be cultivated in a morally negative, neutral, as well as positive way.7

Positive Organizational Scholarship—the Treatment for Misbehavior and Dishonesty in Academic Context

Taking efforts to redefine and reconstruct academic ethos and to create the fundamentals for academic integrity, we should adopt a different perspective to observe and study this process than the one that has caused the crisis (erosion) of academic ethos. It seems that we have wasted too much energy and time for elaborating policies and codes aimed at spying on and punishing those members of academic community who have behaved in an unethical way. We also have spent too much time on creating the tools for preventing unethical behavior inside the higher school that were focused on reducing opportunities for such actions. However, the academic life is very creative, and unethical behavior such as corruption may be compared with a pandemic, a virus that incessantly mutates, changes, creates new strains, and forms immunities to existing medicines such as policies and codes of ethics. At the same time, as noted by Dr. Charles Wankel and I,8 reaction to highly publicized corporate scandals and instances of management misconduct that have eroded public faith (such as Enron, WorldCom, Tyco, Adelphia, and Arthur Andersen) have even suggested that current managerial theories actually contribute to unethical practices.9

This is not to say that the approach to creating academic integrity, based on policies, procedures, and codes focused on preventing from dishonest, unethical behaviors of academic community members, is wrong or inappropriate. These actions should be supported by programs such as the Positive Organizational Scholarship, which promotes academic integrity and human values and virtues. The “old” institutional theory focused on the value-based aspects of leading and organizing;10 in the selfsame manner, Positive Organizational Scholarship returns to basics on topics such as:

1. collective concern about “flourishing,” or succeeding;

2. development of strengths and talents;

3. the dynamics of organization (individual as part of a dynamic, organic group).11

Many intellectual disciplines serve as models, including appreciative inquiry,12 community psychology,13 and humanistic psychology.14 The greatest influence stems from positive psychology, the organizational dynamics allowing individuals, groups, and entire organizations to strive for excellence and flourish. Such flourishing on an organizational level may be manifested in creativity, innovation, growth, resilience, kindness, or other markers revealing that a group is healthy and is performing “above normal.”15

In my study on positive organizational identity, “Virtuousness can be understood as internationalization of moral rules that produces social harmony16 and can be examined as a study of capacity, attributes, and reserve in organizations that facilitate the expressions of positive deviance among organization members.”17 Virtuous organizations “move individuals toward better citizenship, responsibility, nurturance, altruism, civility, moderation, tolerance, and work ethic.”18 Many researchers have reported19 that virtuous organization leads to the development of human strength and healing and cultivates extraordinary individual and organizational performance; this, in turn, leads to flourishing outcomes and the best of the human condition and fosters virtuous behaviors and emotions such as compassion, forgiveness, dignity, respectful encounters, optimism, and integrity, as well as faith, courage, justice, and wisdom.”20

Through a virtues approach to creating academic integrity, schools of higher education strive to develop a specific culture of integrity, promoting an environment in which members behave in responsible, honest, right ways, not because they are afraid of sanctions or because they treat work as their duty but because their “internal self” determines the right way to behave, the only way that can flourish. As noted in my previous works, the formal, ethical infrastructure as well as its external mechanisms cannot guarantee the integrity within academia.21 Every regulation and formal system, even knowledge itself, has limitations. Ethical and moral decisions are made by human beings who have their individual life experience, character, and system of values. Therefore, one can presume that the positive identity of an organization can be managed by developing the company’s morality (by way of developing the moral competences of the staff and implementing the Academic Ethos Management process) and placing more emphasis on abiding and respecting the law and external regulations. It has to be stated, however, that this will not be achieved by implementing institutional reforms or internal systems.

Sooner or later, even a well-functioning system or institution can be perverted by the wrong culture or wrong customs. The problem is that, as far as it is easy to improve the infrastructural dimension of an organization, it is much more difficult to reduce the human-related risk because it became established in the culture. It needs to be emphasized that, although a company’s culture is usually resistant to change, one should make efforts to do so because, unlike Bakan22 who stated in his diagnosis of a contemporary corporation, good people are able to change bad enterprises—they only need to be people with strong moral character and integrity.

The Quest for Integrity in Management Education

It is not necessarily true to state that it is generally known that integrity is essential, “is at heart of what effective business and education is about,” or is a basic characteristic of a leader. The legendary former CEO of General Electric, however, has been known to say that he never held a management meeting where integrity was not mentioned. Great leaders of the past, Weinberger (2010) notes,23 would more likely be cited for courage, wisdom, and integrity.24 Covey and Kouzes and Posner25 put integrity on the top of the list of essential characteristics for effective leadership.26 Organizational leaders are responsible for creating a caring atmosphere within their organizations and for creating norms of integrity and justice in the larger competitive and societal context.27

However, relatively little is known about how management education can prepare managers and professionals to cope effectively with challenges of leading with integrity in multicultural environments.28 Developing future business leaders with capabilities of leading is a challenging but an important task for management educators,29 especially when, as observed by Sandra Waddock, “Trust is central to the effective functioning of all markets. Trust is destroyed, however, when individuals and institutions act without integrity.”30

The quest for integrity in business and education is only partly a reaction to highly publicized corporate scandals and instances of management misconduct that have eroded public faith (such as Enron, WorldCom, Tyco, Adelphia, and Arthur Andersen). As Wankel and I have noted,31 “The quest for integrity is also a result of changes and new demands in the global business environment32 as well as the latest economic crisis.33 Among the sources of these new demands are the expectations of stakeholders that corporations and their leaders will take more active roles as citizens within society and in the fight against some of the most pressing problems in the world, such as poverty, environmental degradation, defending human rights, corruption, and pandemic diseases.”34 In truth, “The collapse of giants like Enron and Arthur Andersen signaled a major turning point in the conversation about corporate ethics and integrity.”35

Business schools can teach the techniques, skills, and tools of, for example, marketing, finance, and operations, but they have lost their ability to install a sense of integrity or moral responsibility in students.36 As Palmer claims,37 education should focus on the “who am I,” rather than solely on the “what” and “how.” Integrity is therefore the use of that wisdom that resides within ourselves.38 But what constitutes the integrity of an individual? Is it possible to teach it, or can the higher schools only encourage ethical behavior through the educational process? And what constitutes the integrity of the whole organizations such as higher schools?

Individual Integrity and the Integrity of a Higher School

The origin of the word “integrity” is grounded in the Latin root integer, which refers to a whole number, suggesting the idea of wholeness. The broadest meaning given to the term integrity in the Oxford English Dictionary39 presents two definitions of integrity: the physical and the moral. Integrity applies to the physical state of undivided wholeness, whether of a united land or unbroken body. Alternately, integrity connotes an unimpaired moral state, characterized by innocence, uprightness, honesty, sincerity, and being without sin.40

According to Kaiser and Hogan,41 the concept of integrity includes two components: honesty and consistency. Honesty is defined as the way in which a person acts within shared ethical standards to meet the expectations of society; consistency is the connection between words and deeds, by behaving in a logical, orderly manner over a period of time and in a variety of contexts.42

Baltimore sees integrity as “the state or quality of being complete, undivided, [and] unbroken.”43 According to Sawyer, Johnson, and Holub, integrity refers to “a consistency across time, consistency across individuals, and consistency across decisions.”44 With regard to the individual, integrity means the successful unity of intellectual, physical, emotional, and spiritual levels.45 Individuals with integrity tell the truth, are trustworthy, hold high moral standards for themselves, and, quite simply, do what they say they are going to do.46

Ayn Rand and Leonard Peikoff define integrity as “loyalty in action to a morally justifiable code of principles and values that promotes the long-term survival and well-being of individuals as rational beings.”47 Carson states that integrity is “an unwavering commitment to acting for the benefit of others, standing up for those who are under attack, loyalty to people to whom we have committed ourselves, acting honorably, and so on.”48 In Solomon’s view, integrity is a balance between institutional loyalty and moral autonomy and is associated with moral humility.49 While principles and policies are important, integrity “involves a pervasive sense of social context and a sense of moral courage that means standing up for others as well as oneself.”50

When we are speaking about leadership, a leader of integrity is aware of his values and acts in a way that keeps those values and their actions aligned.51 According to Peter Drucker, integrity is the “congruence between deeds and words, between behaviour and professed beliefs and values.”52 Only under such conditions will a manager be able to develop the positive university identity and cultivate under core values in a morally positive way as well as effectively manage the organization with the aid of Academic Ethos Management process.53

However, the integrity of a university’s leaders is not enough to build the integrity of the school as a whole. The integrity of a higher school also depends on integrity and moral characteristics of the other participants of academic community, both students and employees. Taking employees into consideration, a higher school may create appropriate recruitment systems based on cultural adequacy of an applicant as well as on his/her level of moral intelligence. But what about students? Is it possible to teach them integrity?

Research indicates that moral development begins at a young age,54 and some state that, rather than teach ethical behavior, universities can only encourage it.55 However, pedagogical support can be developed through carefully designed training of individual awareness for realizing and maintaining integrity. The first quality of integrity is exhibiting strong moral principles regarding what is acceptable and what is not. Students, in effect, must examine what they stand for. The person with integrity knows his or her moral principles and strives to live by them. Such a person is prepared to peacefully defend values and beliefs. Integrity is therefore forged in the activities of day-to-day experience.56

However, the best way to develop the moral character of students and to encourage them to behave with integrity is through example, in one of the best “laboratories” on earth: the university itself.57 Immersing students in a university with integrity helps them to gain insight how to create and perpetuate a culture of integrity.58

• Helps students to develop and enhance their innate capacity to act with integrity in the unexpected and new situations.

• Helps students to become better aware of their values.59

• Helps students to discover their core values as they learn to know themselves holistically.60

• Influences development of students new professional identities.61

• Helps student to experience the benefit of culture of integrity.

But there is still a question: What exactly characterizes the integrity of a higher school? While discussion of the topic naturally begins with human beings, it can also refer to educational systems and business paradigms. For example, LeClair, Ferrell, and Fraedrich defined the notion of integrity management as “uncompromising implementation of legal and ethical principles” that are themselves embodied in the strategic planning process of the firm.62 Paine sees organizational integrity in a broad sense as “honesty, self-governance, fair dealing, responsibility, moral soundness, adherence to principle, and consistency of purpose.”63

We can assume that, according to Paine, organizational integrity is a result of consequent managing by values of a particular organization. This author has also emphasized that it is impossible to create organization’s integrity without the integrity of its participant, and vice versa—the integrity of participants is not enough to construct the integrity of a whole organization. The ethical infrastructure is necessary here. But how does it function in the educational process? Terms such as academic integrity and educational integrity appear frequently in the literature of ethos; the terms, however are a many-headed beast, a mythological, multiheaded Hydra of sorts,64 twisting in many directions with a multiplicity of meanings (with abstract ideas such as “policy” and “right”). In general, the terms have to do with the difference between honest and dishonest practices in educational settings—sometimes blatantly obvious, sometimes subtle, and hidden in nuances and shadows of gray. A generally accepted definition of academic integrity is “honesty in all manners relating to endeavors of the academic environment,”65 but the term also comes to light through behavior such as honesty, trust, fairness, respect, and responsibility.66 Hall and Kuh suggest that one can better understand academic integrity and related behavior by gazing at them through a “cultural lens,” which adjusts to particular foci.67

However, we cannot and should not limit the definition of a university’s integrity solely to academic honesty—the integrity of a higher school transcends honesty. It is a specific organizational culture that is supported with values such as wisdom, courage, humanity, justice, respect, responsibility, fairness, and compassion. It inspires virtuousness of individuals and organizations, and in turn helps an academic community truly flourish. That is why the term of “integrity of higher schools” is a consequence of awareness, a deliberate and consequent managing of values of academic ethos in an ethical way. Constructing academic integrity starts at the top. Academic leaders must exhibit a high level of moral intelligence, wisdom and knowledge, courage, humanity, justice, temperance, and transcendence.68 They must discover and define university ethos and thus make key statements about the central characteristics (core values) of a university. These characteristics form the set of meaning that leaders want an academic community to follow.

Leaders are responsible for transferring a university’s core values from one management generation to another by taking over responsibilities resulting from academic ethos core values and their protection in the name of and for the benefit of a university and academic community through this institutionalization (enacting and maintaining academic ethos core values) in a morally positive manner. Academic leaders model through their day-to-day interactions with the members of academic community and other stakeholders. Moreover, leaders make necessary efforts to maintain core values of academic ethos by appropriate recruitment process, explaining core values, training, rewarding, motivating, and providing mechanisms to control the compliance of academic community members’ activity with the values of a university as well as by action taken to redefine those values. These are the only conditions that will enable a manager to develop the positive academic ethos and cultivate core values in a morally positive way. Positive corporate identity is vital; it must be communicated to all employees and stakeholders through Academic Ethos Management. The critical point for the future behavior of the company’s employees and the organization itself is the way in which employees interpret the organization’s actions. It is never easy to make sense of an organization’s goals, achievements, and position.

Every organization is a complex structure that has its own history, traditions, and set of activities enabling members to understand the organization’s activities, goals, and values. Each member analyzes the organization’s actions in order to better understand them. The member infers what an organization stands for and interprets organizational actions in response to specific events.69

Interpretation of an organization’s actions influences the way in which members perceive the organization. A member’s interpretations relates to some degree to the kind and degree of virtuousness of actions. “Virtuous organizational action” is the perceived exercise of collective behavior that indicates that the organization follows core values leading improvement on both moral and ethical levels.70 The financial performance of an organization is directly proportional to the degree of virtuousness of their actions.

This is evidence that positive organizational identity and members’ identification with and attachment to their organization results, to some extent, from the perceived virtuousness of organization’s actions. Therefore, if an organization acts in accordance with its core values (walking the talk), and its behaviors are perceived as humane, just, and courageous, it has a positive influence on organizational identity (meaning that members recognize their collectives).71 This, in turn, contributes to positive behavior toward the organization’s positive word-of-mouth recommendations, encourages employees to act ethically and legally, strengthens positive emotions of an organization’s members, and reflects in the virtuous self-constructs of members.72

A typical organization’s actions can be described as “walking the talk,” while the positive corporate identity (core values) requires implementing the Academic Ethos Management process in a morally positive way. Organizational action can be described as humane when it involves actions such as helping and taking care of organizational members or a larger society, through which they feel appreciated and are treated with dignity and respect. Moreover, courageous organizational action is undertaken by the organization in a spontaneous way in order to pursue “what is right,” irrespective of the risks it may bring, and which aims at securing social well-being and moral improvement.73 Only such an organization, which meets all the aforementioned attributes, can be perceived as one that is able to build a prosperous academic community, distinguished by its integrity in teaching, learning, conducting research, and providing services.

However, we need to remember that a college or university does not act in a vacuum but in a specific environment, the micro and macro one. The external environment of a higher school has an impact on the integrity of a higher school. The general environment (sociocultural, political, or economic, for example) has an indirect impact on a university; the external-task environment (like government regulation, funding for scientific work, job opportunities for trainees and researchers, journal policies and practices, and the policies and practices of scientific societies)74 has a direct impact on the integrity of a higher school. When they are implemented, government regulations concerning scientific research conduct, reporting study results, reviewing scientific works, protection of authorship rights or reporting unethical behaviors in a scientific environment regulate academic work and have a profound impact on the members of an academic community. A similar situation may be observed in policies and practices implemented by scientific journals, stating that their editors must be vigorous in their dissection of work, particularly “in such areas as authorship practices, disclosure of conflicts of interest, duplicate publication, and reporting of research methodologies, the scientific community receives an important message about the role of integrity in research.”75

We should not forget about the current labor market that becomes more and more competitive for scientists and for academic teachers. It causes a specific pressure on people of science to strive more and perform better in the short term. It may result in unethical behavior such as taking shortcuts, for example, through disseminating sensational research results that are not honest or by gaining funds for scientific research through unethical practices and agreements with external organizations.

The practice provides us with numerous examples of such unethical conduct. Well-known Dutch psychologist Diederick Stapel admitted that, for many years, he has been falsifying research results that were published in renowned journals such as Science.76 Wicher from the University of Amsterdam confirmed that Stapel was not an exception, as in psychology the results usually are not commented by others. Jonathan Schooler, a psychologist from the University of California in Santa Barbara, affirmed that some scientists embellish their research results to be more interesting for their publication. That is why the challenge for a higher school is to create an organizational culture supported by appropriate ethical infrastructure that will maintain a high level of integrity within the academic community.

In conclusion, academic integrity is the effect of a compound process of coordinated actions in the following areas:

• leaders’ integrity;

• integrity of a higher school as an organization;

• integrity of members of academic community;

• integrity of environment of a higher school.

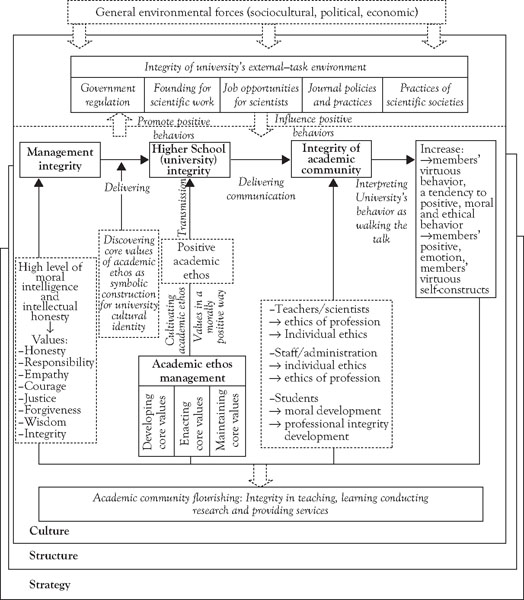

Figure 10.1 illustrates a conceptual framework of academic integrity based on positive academic ethos.

Figure 10.1. Conceptual framework of academic integrity based on Positive Academic Ethos.

Source: Author’s own study.

I have a deep conviction and belief that a combination of a positive academic ethos and the integrity of academic community with positive meaning that academic communities impute to their collectives (as a result of implementing university actions as virus) with positive leadership and integrity of academic environment can install values, meaning, and purpose in university’s life and results in academic flourishing demonstrated by integrity in teaching, learning, conducting research, and providing services.

The road to academic integrity is a very difficult and long process, but it is the only possibility for a university to fulfill its mission of discovering the truth, developing knowledge, playing a leading role in the development of democratic principles and free thinking, and educating citizens who will make this world a better place.