Chapter 8

CEO Performance Evaluation and Executive Compensation

CEO Performance Evaluation1

Regular, purposeful CEO performance evaluation by the board is a cornerstone of effective governance. According to Spencer Stuart’s 2011 Board Index, 94% of S&P boards surveyed said their CEO’s performance is evaluated annually. Evaluation of individual directors is becoming more common; 34% of boards did it in 2011, up significantly from previous years. Twenty-one percent of boards now review performance at every level—the full board, committees, and individual directors.

Performance evaluation at the CEO level is difficult. Rivero and Nadler (2003) note that the difference between a good evaluation process in which everyone wants to participate and one that becomes mere window dressing is the CEO’s attitude toward the process and reactions to the feedback. At the same time, an ad hoc process sprung on the CEO can send the wrong signals about the nature of the board and CEO relationship. Both the CEO and the board need to make an investment to ensure that the process is well planned and part of the normal course of business. Minimizing potential problems at the outset, therefore, raises the odds of creating a successful, sustainable process. Common pitfalls to look for include the following:

•Uncertainty concerning roles and responsibilities. Confusion over roles and responsibilities is not uncommon. A clear charter helps, as do descriptions of roles and accountabilities, and timelines and milestones. The director leading the process (typically the chair of the compensation committee) should actively work with other board members to clarify expectations for their participation.

•Lack of time and energy. Time is the enemy of many board processes, and an elaborate CEO evaluation process that requires significant input from the board may be met with resistance. Yet, a well-designed evaluation brings structure and efficiency to many of the board’s other responsibilities, such as oversight and setting executive compensation, thereby actually saving directors’ time in the long run.

•Disagreement over criteria for assessment. Considerable debate over the appropriate criteria for assessing performance is normal and healthy. Before moving forward, however, the CEO and the board must agree on the dimensions of performance and objectives. Disagreements should be resolved by referring to the strategy and business needs of the organization.

•Lack of direct information about nonquantitative performance. Financial and key operational metrics are usually readily available, but measures of softer dimensions, such as leadership effectiveness, often have to be designed specifically for the purpose of the evaluation.2

A well-thought-out process analyzes both past performance and sets goals for the future, and therefore assists the compensation committee of the board in making decisions about the CEO’s future compensation and employment. A good process helps the CEO and the board to establish focus on the company’s future direction by specifying a set of strategic objectives. This goal-setting aspect of the evaluation can also serve as part of the CEO’s ongoing leadership development, with the board providing feedback about areas where the CEO needs to do a better job, learn new skills, or focus additional attention.

An effective CEO evaluation process, therefore, looks backward, focusing on accountability and rewards for past performance, as well as forward, focusing on future objectives and whether the CEO has the vision, strategy, and personal capabilities to achieve these objectives. Although these are distinct objectives, in practice they are often integrated into the same process. Time constraints often force the board to evaluate the CEO’s performance over the previous year while simultaneously making compensation decisions, setting next year’s targets, and discussing specific areas for improvement, often in a single meeting. As Rivero and Nadler observe, this is unfortunate because when the two objectives are not clearly separated, there is a clear danger that neither gets served very well.3

When time is short the developmental part of the evaluation is often skipped altogether, forcing the board to use the compensation review to set the CEO’s future objectives. This approach is likely to emphasize what the CEO is expected to achieve (usually framed in terms of short-term financial targets) over how the CEO is expected to behave (such as giving more attention to developing future leaders). When this happens, the CEO is unlikely to receive candid, detailed feedback about his or her behavior and personal impact.

Dimensions

Defining an effective set of dimensions to be evaluated represents a major challenge. Based on the distinction made above between a CEO’s impact on corporate performance and his or her actions and effectiveness as a leader, Rivero and Nadler identify three generic sets of measurements of CEO performance: bottom-line impact, operational impact, and leadership effectiveness.

1.Bottom-line impact. Most CEO evaluation and “pay-for-performance” plans are based on the assumption that the top executive has a direct and significant impact on corporate performance, and therefore hold CEOs accountable for the company’s overall financial health. While important, relying solely on shareholder-oriented, accounting-based bottom-line measures as indicators of CEO performance has severe deficiencies. Most CEOs know that their ability to affect the company’s bottom line is indirect and often limited.

2.Operational impact. Operational impact refers to the CEO’s influence on the company’s effectiveness in operational areas, such as customer satisfaction, new product introduction, or productivity enhancement, and how well the firm implements its strategy. Operational impact measures often give a better indication of a company’s underlying potential to create value because they are directly related to the immediate stock price, which is subject to market-wide volatility. While still subject to external and internal forces outside of the CEO’s immediate control, this type of performance is more closely related to the CEO’s actions.

3.Leadership effectiveness. Leadership effectiveness addresses how well the CEO carries out his or her responsibilities, both in terms of executing specific role responsibilities—identifying a successor, meeting with key customers and investors, developing a long-term strategy—and the quality of those actions—communicating with external stakeholders, energizing the organization, and gaining the confidence of investors.4

The three categories described above are generic. While the specific dimensions and objectives that are used vary for each company, there are some general principles that leading companies follow in selecting CEO performance objectives. First, their evaluations reach beyond bottom-line performance. Financial measures of corporate performance, while critical, capture only one aspect of CEO performance. To compensate for some of the limitations of bottom-line measures, it is important to include objectives that reveal how the CEO behaves as a leader, as well as the CEO’s impact on the effectiveness of the organization. Second, they focus on a manageable number of objectives. One risk in attempting to capture multiple aspects of CEO performance is that the list of performance dimensions may grow too large to be workable. Too few dimensions, on the other hand, cause the process to be dominated by short-term financial objectives. Best practice is to use between 5 and 10 dimensions. Third, they use separate objectives for chairman and CEO performance, even if it involves the same person. In most North American companies, the CEO also serves as chairman of the board. It is important to evaluate his or her performance in both roles. The chairman’s role can be assessed either as one component of a formal board evaluation process, or the dimensions of chairman effectiveness can be added to the CEO’s evaluation process. Fourth, they define measures for each objective. Creating explicit measures to track performance against the particular objective is relatively simple for all bottom-line and most operational impact objectives. For “softer” dimensions this is more of a challenge but can be achieved. For example, leadership behaviors can be measured through rating methods that ask board members to indicate how often the CEO demonstrates desired behaviors and what impact these have. Finally, they specify performance levels for each rating measure. Explicit measures for each objective assist in setting performance expectations with the CEO. Specificity helps create shared understanding of the performance standards between the CEO and the board.

Best practice also suggests that an effective CEO performance evaluation process is integrated with the company’s calendar of business planning and compensation review: Step 1 is focused on defining the CEO’s objectives. Before the start of the fiscal year, the CEO should work with the compensation committee of the board to establish key business objectives for the coming year. Using the strategic plan as a starting point, this dialogue should produce an initial set of personal performance targets and associated measurements. After reviewing and amending them if needed, the final set should be discussed and approved by the full board. These targets can then be used to create an integrated goal-setting process that aligns the objectives of each leadership level in the company.

Step 2 is a mid-year review. Six months into the year, the compensation committee and the CEO should review the targets and progress against them. Such a mid-year review can provide great value for two reasons. First, it helps the board see how the CEO is meeting or exceeding targets and to identify areas that require closer attention. Second, it provides an opportunity to amend the targets in light of changed circumstances, such as rapidly changing business conditions.

Step 3 is the year-end assessment. At the end of the fiscal year, the CEO’s performance should be measured against the previously established objectives. As part of this step, the CEO should be invited to provide a self-evaluation and be given an opportunity to address areas where targets were not met. The self-assessment is shared with the compensation committee and then the full board for input on the CEO’s performance. Evaluations by all board members go to the compensation committee, which uses the results to determine the portion of the CEO’s pay that is linked to performance. Before providing feedback to the CEO, the evaluation should first be discussed by the board in an executive session, that is, without the CEO or other inside directors present.5

Executive Compensation

A reasonable and fair compensation system for executives and employees is fundamental to the creation of long-term corporate value. However, the past two decades have seen an unprecedented growth in compensation for top executives and a dramatic increase in the ratio between the compensation of executives and their employees. “Runaway” executive compensation has become the subject of editorials, political debates, and battles between directors and shareholders. The reasons are not hard to understand; the numbers involved are large.

The federal securities laws require clear, concise, and understandable disclosure about compensation paid to CEOs, CFOs, and certain other high-ranking executive officers of public companies.6 Documents that include information about a company’s executive compensation policies and practices that need to be filed with the SEC include: (1) the company’s annual proxy statement; (2) the company’s annual report on Form 10-K; and (3) registration statements filed by the company to register securities for sale to the public.

In the annual proxy statement, a company must disclose information concerning the amount and type of compensation paid to its chief executive officer, chief financial officer, and the three other most highly compensated executive officers. A company also must disclose the criteria used in arriving at the executive compensation decisions and the degree of the relationship between the company’s executive compensation practices and corporate performance. This information can be found in several separate disclosure items.

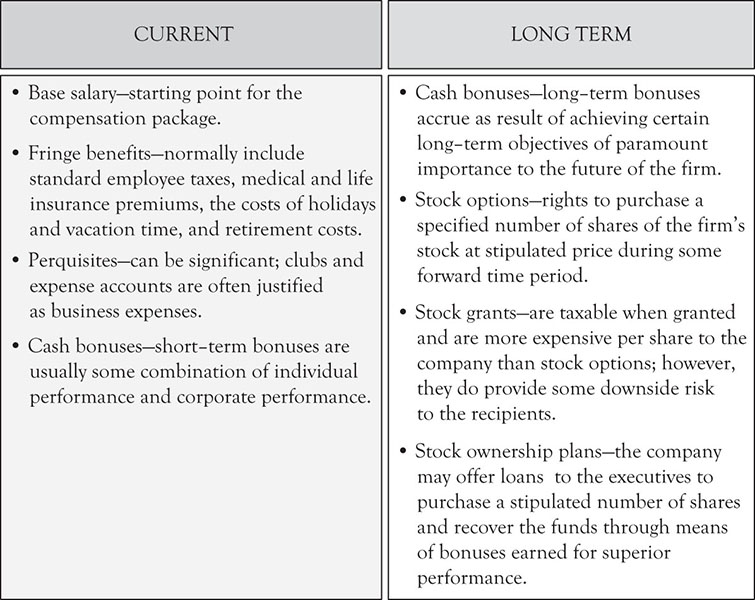

The Summary Compensation Table is the cornerstone of the SEC’s required disclosure on executive compensation. This table provides, in a single location, a comprehensive overview of a company’s executive pay practices. It sets out the total compensation paid to the company’s chief executive officer, chief financial officer, and three other most highly compensated executive officers for the past 3 fiscal years. The Summary Compensation Table is followed by other tables and disclosure containing more specific information on the components of compensation for the last completed fiscal year (Figure 8-1). This disclosure includes, among other things, information about grants of stock options and stock appreciation rights; long-term incentive plan awards; pension plans; and employment contracts and related arrangements. In addition, the Compensation Discussion and Analysis (“CD&A”) section explains all material elements of the company’s executive compensation programs.

Figure 8-1. Typical components of CEO compensation.

How Much Is Too Much?

Median CEO pay in 2011 rose 2% to $9.6 million, based on 138 Standard & Poor’s 500 companies that have reported CEO pay for that year and that had the same CEO for all of 2010 and 2011, according to a USA Today analysis of data from GMI Ratings on proxies that have already been filed.7

A 2% raise in 2011 seems low, given some of the double-digit raises CEOs have received in years past and given that S&P 500 corporate profit rose 15% in 2011 but it comes just 1 year after C-suite occupants saw their total compensation return to prerecession levels thanks to one of their biggest increases in pay in years.

The latest rise shows that despite the widespread concern expressed in recent years over the large pay packages many CEOs receive and attempts to reform, boards appear to be ready again to approve increases. Also, it has not gone unnoticed that CEO pay continues to escalate even as companies are reluctant to add more personnel to their payrolls. Unemployment in many sectors remains stubbornly high and although employees are starting to see some wage growth too, real average weekly earnings for all employees, adjusted for inflation, have fallen 1.2% from the October 2010 peak, according to Bureau of Labor statistics.

A closer look at proxies filed shows the following:

•Significant growth in stock and options pay. CEOs received stock and option grants worth $6.3 million, an increase of 8% from 2010.

•The median value of just stock grants, not including options, rose 10% to $3.6 million, making it again the largest source of CEOs’ total pay.

•Moderation of mega-bonuses. The median bonus paid to CEOs was $2.1 million, down 3% from 2010 as some CEOs missed performance targets. That is in stark contrast to the 47% jump in the 2010 median bonus paid last year.

•Windfall from cashing in stock. Thanks to the rising stock market, executives are being rewarded handsomely for stock and options they were given in years past.

The median amount that CEOs actually took home, which includes salary and cash bonuses, as well as stock options awarded in previous years that vested or were cashed in, was $7.8 million, up 12%. The top earner in 2011 was McKesson CEO John H. Hammergren, with $131 million in total pay. This amount included $6.3 million in salary and bonus payments and $112 million from the exercise of vested stock options. The next four top-paid chief executives, also earning most of their pay from exercised stock options or vested stock awards, are Forbes billionaire Ralph Lauren of Ralph Lauren ($67 million); Michael D. Fascitelli of Vornado Realty ($64 million); Richard Kinder of Kinder Morgan ($61 million); and David M. Cote of Honeywell International ($56 million).

Seventeen female CEOs made to the highest-paid list in 2011. At the top is Marissa Mayer, incoming CEO at Yahoo. Her initial compensation package is valued at nearly $60 million—big for any incoming CEO—but one of the biggest ever awarded to a woman. And, depending upon her length of stay and performance as she tries to effect a turnaround of the struggling Internet company, she could earn much more. Based on the company’s filing with the Securities and Exchange Commission, Mayer’s compensation package includes the following:

•Annual salary: $1 million.

•Potential annual bonus: $2 million.

•Annual equity award: $12 million—50% in restricted stock, 50% in stock options.

•A one-time retention award worth $30 million—50% in restricted shares that vest over 5 years, 50% in stock options.

•A “make whole” stock grant valued at $14 million to cover compensation Mayer forfeited after leaving Google, where she had worked since 1999. The shares fully vest in 2014.

•Up to $50,000 a year for security expenses.

Mayer’s employment contract with Yahoo has no specified length. Instead, she serves “on at-will basis,” according the SEC filing. But for each year she remains, she is eligible for at least $12 million in annual equity grants and bonuses of up to $2 million. Mayer’s pay package reflects the escalating costs of CEO hires. Last year, retailer J.C. Penney paid Apple retail store chief Ron Johnson more than $50 million. And when Apple replaced an ailing Steve Jobs, it gave Chief Financial Officer Tim Cook stock grants valued at more than $375 million. A stark contrast is provided by five executives who only take $1 in annual salary, and all their other compensation is tightly linked to corporate performance. Four are Forbes billionaires: Oracle‘s Larry Ellison, Google’s Larry Page, Hewlett Packard’s Meg Whitman, and Kinder Morgan’s Richard Kinder; the other executive is Whole Foods’ John Mackey.

Of course, simply comparing a CEO’s compensation to that of an average worker is not appropriate because it does not take value creation into account. But it makes for good press. So do high-profile reports of CEOs receiving compensation packages worth millions of dollars while shareholders lost a major part, if not all, of their investment and workers suffered benefit or job cuts. Such headlines fan the perception that despite new NASDAQ and NYSE rules mandating greater board autonomy, many directors remain beholden to management when it comes to compensation. Excessive CEO pay takes dollars out of the pockets of shareholders—including the retirement savings of America’s working families. Moreover, a poorly designed executive compensation package can reward decisions that are not in the long-term interests of a company, its shareholders, and employees.

The CEO pay debate first achieved international prominence in the early 1990s. An important milestone was the publication of Graef Crystal’s exposé on CEO pay, In Search of Excess, which clearly demonstrated the prevalence of excessive executive compensation practices in U.S. companies.8 Time magazine labeled CEO pay as the “populist issue that no politician can resist,” and CEO pay became a major political issue in the United States.9 Legislation was introduced in the House of Representatives disallowing deductions for compensation exceeding 25 times the lowest paid worker, and the Corporate Pay Responsibility Act was introduced in the Senate to give shareholders more rights to propose compensation-related policies. The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) preempted the pending Senate bill in February 1992 by requiring companies to include nonbinding shareholder resolutions about CEO pay in company proxy statements, and announced sweeping new rules affecting the disclosure of top-executive compensation in the annual proxy statement in October 1992.10 In 1994, the Bill Clinton tax act (the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1993) defined nonperformance-related compensation in excess of $1 million as “unreasonable” and therefore not deductible as an ordinary business expense for corporate income tax purposes.

Ironically, although the objective was to reduce “excessive” CEO pay, the ultimate outcome was a significant increase in executive compensation, driven by an escalation in option grants that satisfied the new IRS regulations and allowed pay significantly in excess of $1 million to be tax deductible to the corporation. Once the act defined $1 million compensation as reasonable, many companies increased cash compensation to $1 million and then began to add on performance-based pay components that satisfied the act.11

Stock Options

A principal driver behind the dramatic increases in executive pay in large U.S. firms over the past three decades has been the explosion in grants of stock options. A stock option is a right to buy shares at a particular price—the so-called strike price—at some future date. If an employee receives an option to buy 100 shares at a $5 strike price and the stock has risen to $10 by the vesting period, the employee can buy the stock at the lower price and reap a quick profit. The idea is to align employees’ interests with those of shareholders’ to encourage productivity and profits. In reality, the excessive use of options created a mechanism for companies to transfer profits directly to employees—mostly top executives—at the expense of shareholders.

The significant increase in the use and value of stock option awards was driven by a greater focus on equity-based compensation and changes in disclosure and tax rules that reinforced stronger linkages between stock performance and executive pay. Regrettably, there also is evidence that many boards and executives viewed stock options as a low-cost or even cost-free way to compensate executives.

In economic terms, the cost to the corporation of granting an option to an employee is the opportunity cost the firm gives up by not selling the option in the market, and that cost should be recognized in the firm’s accounting statements as an expense. When a company grants an option to an employee, it bears an economic cost equal to what an outside investor would pay for the option. However, because employees are more risk averse and undiversified than shareholders, and because they are prohibited from trading the options or taking actions to hedge their risk (such as short-selling company stock), employees will naturally value options less than they cost the company to grant. Thus, because the company’s cost can exceed the perceived value to the employee, rather than being a low-cost way of compensating employees stock options constitute an expensive compensation mechanism. Its use can therefore only be justified when the productivity benefits the company expects to get from awarding costly options exceed the pay premium that must be offered to employees receiving the options.

Until recently, many U.S. companies were not very diligent in assessing the cost and value of options and treated options as being cost-free. Option grants do not incur a cash outlay and, until the recent change in accounting rules, did not bear an accounting charge. Moreover, when an option is exercised, the company incurs no cash outlay and receives a cash benefit in the form of a tax deduction for the spread between the stock price and the exercise price. These factors make the “perceived cost” of an option to the company much lower than the economic cost, and often even lower than the value of the option to the employee. As a result, many options were granted to many people, and options with favorable accounting treatment were preferred over better incentive plans with less favorable accounting treatment.

The impact of the excessive use of stock options, especially by leading technology companies, however well intended (ostensibly to attract, reward, and retain executive talent), goes well beyond the realm of executive compensation; it transferred a significant amount of wealth from shareholders to employees.

More recently the image of stock options was tainted further by two illegal acts—backdating and spring loading. Backdating involves picking a date when the stock was trading at an even lower price than the date of the options grant, resulting in an instant profit. Spring loading involves the granting of options right before a company announces news guaranteed to drive up the share price.

Backdating and spring loading violate existing accounting rules, state corporate law, federal securities laws, and tax laws. In a few instances, the U.S. Department of Justice has concluded that CEOs who backdated options committed criminal fraud. The recent backdating scandals forced numerous CEOs and other corporate officials to resign or be fired, and the SEC continues to investigate possible options backdating at more than 100 companies.

Backdating and spring loading also harm shareholders. The money paid to CEOs who improperly backdate or spring load their stock options belongs to shareholders, and when companies have to restate their earnings and pay additional taxes, shareholders lose even more. Since the Sarbanes-Oxley Act became law in 2002, companies must report stock options grants to their executives within 2 business days. Thanks to this investor protection law, it is much harder for executives to backdate stock options. But, Sarbanes-Oxley notwithstanding, CEOs can still inappropriately time stock option exercises based on inside information or by spring loading their stock option grants.

In the last few years, investors submitted dozens of shareholder proposals seeking to limit executive severance and realign pay with performance. Although boards have tended to resist such proposals, contending they constrain their ability to attract, retain, and motivate managers, they have started to change their pay practices to better align interests with shareholders. PepsiCo, for example, replaced its traditional stock options with performance-based restricted shares that are worthless unless earnings targets are met.

Golden Parachutes

A “golden parachute,” or change-of-control agreement, is an agreement that provides key executives with generous severance pay and other benefits in the event that their employment is terminated as a result of a change of ownership of the company. Golden parachutes are voted on by the board and, depending on the laws of the state in which the company is incorporated, may require shareholder approval. Some golden parachutes are triggered even if the control of the corporation does not change completely; such parachutes open after a certain percentage of the corporation’s stock is acquired.

Golden parachutes have been justified on three grounds. First, they may enable corporations that are prime takeover targets to hire and retain high-quality executives who would otherwise be reluctant to work for them. Second, since the parachutes add to the cost of acquiring a corporation, they may discourage takeover bids. Finally, if a takeover bid does occur, executives with a golden parachute are more likely to respond in a manner that will benefit the shareholders. Without a golden parachute, executives might resist a takeover that would be in the interests of the shareholders to save their own job.

As golden parachutes have grown more prevalent and lucrative, they have increasingly come under criticism from shareholders. Their concern is understandable since many golden parachute clauses can promise benefits well into the millions. For example, Nabors Industries’ former CEO, Gene Isenberg, is scheduled to receive $126 million when he exits as chairman, and IBM CEO Sam Palmisano took home $170 million when he stepped down in 2012. They follow Google’s Eric Schmidt, who received $100 million in stock after leaving as CEO. Worth it or not, these examples underscore the pay inequity that has made corporate America’s elite ripe targets of populist movements such as Occupy Wall Street. What particularly bothers critics is that many golden parachute agreements do not specify that an executive has to perform successfully to be eligible for the award. In a few high-profile cases, executives cashed in their golden parachute while their companies had lost millions of dollars under their stewardship and thousands of employees were laid off. Large parachutes that are awarded once a takeover bid has been announced are particularly suspect; they are little more than going-away presents for the executives and may encourage them to work for the takeover at the expense of the shareholders.

In previous years, it was difficult to ascertain the value of executive severance packages until an executive actually left a company. New SEC executive compensation disclosure rules now require companies to disclose the terms of written or unwritten arrangements that provide payments in case of the resignation, retirement, or termination of the “named executive officers” or the five highest paid executives of a company. The SEC rules also require companies to detail the specific circumstances that would trigger payment and the estimated payment amounts for each situation.

Though this new rule will show whether an executive has an excessive severance package, it does not provide investors with a way to limit them. Congress is considering legislation that will require public companies to hold a nonbinding vote on executive pay plans, including an advisory vote if a company awards a new golden parachute package during a merger, acquisition, or proposed sale.

Despite best efforts to reign in and realign CEO pay, competition for talent keeps driving compensation to higher levels. Persistent high levels of CEO turnover are an important factor. Another factor pushing up compensation is the increasing prevalence of filling CEO openings through external hires rather than through internal promotions. CEOs hired from outside typically get paid more than CEOs promoted from within. In addition, CEOs in industries with a higher prevalence of outside hiring are paid more than CEOs in industries characterized by internal promotions. The competitive CEO job market also makes retention a more critical issue, further driving up pay, as boards will err on the side of paying more because of the difficulty, disruptiveness, time, and cost associated with finding a replacement.

The growing intensity of the competition for talent is not limited to CEOs. Compensation committees increasingly deal with the compensation demands of second-tier managers, especially CFOs. And even if senior executives are not threatening to leave, base salaries and target levels for bonuses are getting higher because of “benchmarking.” Many boards, acting on the advice of compensation consultants, have adopted a policy of setting their CEO’s pay above median levels, a practice known among pay critics as the “Lake Wobegon” effect where almost every CEO is considered above average.

The Role of the Compensation Committee

The board of directors is responsible for setting CEO pay. Well-designed executive compensation packages are tied to an effective performance evaluation process, reward strong current performance, and provide incentives for creating long-term value. They must be structured to attract, retain, and motivate the right talent, and avoid paying premiums for mediocre or poor performance, or worse, for destroying long-term value. They should be designed to align the interests of management with those of shareholders and other stakeholders in both the short and the long term. While responsibility for CEO performance evaluation (and that of other key senior executives) often rests with the full board, determining appropriate compensation policies for the company’s CEO and most senior executives normally is the task of the board’s compensation committee.

The role of the compensation committee has changed significantly in recent years. In the wake of the Sarbanes-Oxley legislation, the new SEC rules, and other regulations, many boards are reevaluating the composition, charter, and responsibilities of the compensation committee. This also reflects the fact that the mission of the compensation committee has grown in recent years to include two distinct elements. Strategically, the committee has the responsibility to determine how the achievement of the overall goals and objectives of the company is best supported by specific performance-oriented compensation policies and plans. This includes designing and implementing executive compensation policies aimed at attracting, retaining, and motivating top-flight executives. Administratively, the committee has responsibility for ascertaining that the company’s executive compensation programs (covering base salary programs, short- and longer-term incentives, as well as supplemental benefits and perquisites) remain competitive within the market.

Within the context of this expanded mission, compensation committees must

•provide the necessary transparency required by the regulations through proper disclosures within the company’s SEC filings;

•recommend for board approval the specific performance criteria and annual and longer term performance targets for awards under the executive compensation program;

•review the performance of the top five officers relative to the achievement of performance objectives for use in calculating award levels under the executive compensation program;

•provide periodic oversight of all short- and long-term incentive plans, perquisites, and other benefits covering the company’s executives to ensure that such programs meet the stated performance goals of the organization;

•ensure that all committee business is conducted in a moral and ethical fashion, maintaining the highest levels of personal conduct and professional standards, and taking action to notify the board of any issues—as well as the necessary corrective action—that may affect the committee’s ability to objectively fulfill its duties and responsibilities.

Executive Compensation: Best Practices

The challenges facing compensation committees today are formidable. Increased public scrutiny, stronger pressure from shareholders, new regulations, and intense competition for executive talent are causing compensation committees to change their focus beyond providing transparency and compliance to creating value by adopting compensation policies and structures that assist in attracting, developing, and managing executive talent and driving performance.

A review of best practices of companies with a track record of overseeing successful management teams suggests that the most effective compensation committees do the following:

•Think strategically about executive compensation. Proactive compensation committees integrate their compensation policies with the company’s overall strategy. A move to a new business model, for example, may require different incentives from other growth strategies.

•Integrate compensation decisions with succession planning. Very few events have a more dramatic impact on a firm than the unexpected loss of a successful CEO. Winning companies have a succession plan in place that not only addresses “who takes over and when,” but also “why” and “how.” This requires that the board agrees on the set of skills and competencies needed to execute the company’s long-term vision—that is, adopts an objective framework for identifying the right talent to implement the company’s chosen strategy.

•Understand the limitations of benchmarking. External benchmarking is widely blamed for escalating executive pay levels. Analysis methods should not be blamed, however. The problems arise in their application. Benchmarks can be useful for assessing the competitiveness of compensation packages but should only be considered within the context of performance.

•Understand how executives view compensation issues. Executives often take a different perspective from directors in looking at compensation issues. Whereas boards are preoccupied with issues, such as the associated accounting expense, tax consequences, potential share dilution, alignment with the business strategy, and administrative complexity, executives often take a more personal, risk-based perspective.

•Communicate with major shareholders. Investors increasingly value an open dialogue about matters, such as potential board nominees or equity grant reserves; their input can give compensation committees a sense of broader shareholder views.

•Carefully select, monitor, and evaluate their advisers and advisory processes. NYSE listing standards require boards to evaluate themselves at least annually, and board self-evaluations are quickly becoming a governance best practice. The evaluation process should include the performance of consultants and other outside advisers.

Key Points to Remember

1.Regular, purposeful, CEO performance evaluation by the board is a cornerstone of effective governance.

2.A well-thought-out process analyzes both past performance and sets goals for the future, and therefore assists the compensation committee of the board in making decisions about the CEO’s future compensation and employment.

3.A good process helps the CEO and the board to establish focus on the company’s future direction by specifying a set of strategic objectives. This goal-setting aspect of the evaluation can also serve as part of the CEO’s ongoing leadership development, with the board providing feedback about areas where the CEO needs to do a better job, learn new skills, or focus additional attention.

4.A good process focuses on three generic sets of measurements of CEO performance: bottom-line impact, operational impact, and leadership effectiveness.

5.A reasonable and fair compensation system for executives and employees is fundamental to the creation of long-term corporate value.

6.In the annual proxy statement, a company must disclose information concerning the amount and type of compensation paid to its chief executive officer, chief financial officer, and the three other most highly compensated executive officers. It also must disclose the criteria used in reaching executive compensation decisions and the degree of the relationship between the company’s executive compensation practices and corporate performance.

7.Excessive use of stock options, especially by leading technology companies, however well intended (ostensibly to attract, reward, and retain executive talent), has effectively transferred a significant amount of wealth from shareholders to employees.

8.The role of the compensation committee has changed significantly in recent years. In the wake of the Sarbanes-Oxley legislation, the new SEC rules, and other regulations, many boards are reevaluating the composition, charter, and responsibilities of the compensation committee.