CHAPTER 5

Goodness Matters

A growing body of evidence shows that companies can do well by doing good. But that’s only part of the story in the world taking shape. The individual trends outlined in Chapters 2, 3, and 4—when taken together—indicate that goodness is rapidly becoming necessary to doing well.

What’s more, the convergence of the trends we’ve identified calls for a comprehensive response. Many companies during the past decade have launched disparate initiatives such as becoming an employer of choice, reducing carbon footprints, and beefing up compliance efforts. But firms that aim to succeed in sustainable ways must move to become good companies through and through.

This chapter summarizes some of the best available hard-nosed evidence that companies are doing well by doing good and risk doing poorly by doing bad. Although much of this evidence is based on large, publicly traded U.S.-based firms, the arguments presented in earlier chapters strongly point to the growing imperative for all organizations—private or public, large or small—to become thoroughly worthy.

Doing Well by Doing Good

The stock market—despite all of its wild swings and, at times, seeming irrationality—provides one of the best available lenses for understanding the payoff that good companies enjoy over an extended period of time.1 To be sure, the performance of any given stock can be erratic, as can the performance of the entire market at any point in time. But over the long haul, the performance of “good companies” (relative to the market) has a great deal to teach us.

Fortune magazine’s annual list of the best companies to work for provides one of the best available methods for looking at how being a good employer relates to subsequent performance in the stock market.2 From 1998 to 2009 the average annual return on a portfolio of the (publicly traded) companies on this list was 10.3 percent, compared to an annual average return for the S&P 500 (the standard U.S. benchmark) of 3.0 percent.3 Even after controlling for company characteristics, the companies on this list outperformed risk-adjusted industry benchmarks. They also exhibited significantly more positive earnings surprises—occasions when their quarterly earnings surpassed what analysts predicted they would be—than their industry benchmarks.4

While this evidence does not necessarily prove that being a good employer causes these results, the findings strongly suggest companies can do well by doing good as employers.

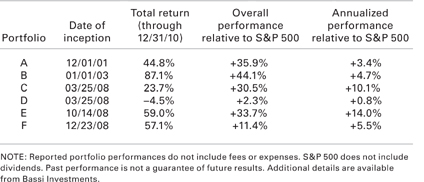

And it is not the only evidence along those lines. Dan and Laurie are registered investment advisers and since 2001 have been investing in a series of portfolios based on how well firms manage and develop their employees. The performance of these “human capital management” portfolios is listed in the table on the following page.

The longest running of these portfolios—Portfolios A and B—are based on a very simple investment strategy: firms that invest more in educating, developing, and training their employees subsequently perform better (on average) than those that spend less.5 Once again, this finding does not prove that investing in employees causes better subsequent stock performance.6 But the finding is striking. It suggests that executives (and investors) should pay attention to the importance of being a good employer.

Portfolios C to F are each based on broader (but more difficult to quantify) concepts of human capital management. Each of the portfolios uses a somewhat different process for identifying firms with superior capabilities for managing and developing employees. For example, one portfolio is heavily weighted to firms that do an exceptionally good job of employee performance management (a specific aspect of being a good employer). Another portfolio is heavily weighted to firms that use rigorous quantitative analysis to help them invest wisely in employees’ development.

Performance of Human Capital Portfolios, Relative to S&P 500

Although the track record on these portfolios is short, the early signs are promising.

Similarly, other data shows that a focus on responsibility or sustainability pays off. The FTSE KLD 400 Social Index, a stock index constructed using environmental, social, and governance factors, has outperformed the S&P 500 since its inception in 1990. The FTSE KLD 400 Social Index slightly underperformed the S&P 500 during the year that ended July 31, 2010. But it had outpaced the S&P 500 on a three-year and five-year basis.7 And SAM, the investment company behind the Dow Jones Sustainability Indexes, says its in-house research and external academic empirical work suggest that “there is a positive and statistically significant correlation between corporate sustainability and financial performance, as measured by stock returns.”8

Sustainability also spelled success in the stock market during the recent financial crisis, according to a study by consulting firm A. T. Kearney. Although the study covered a relatively short time frame of six months, the findings were telling. A. T. Kearney discovered that in 16 of 18 industries studied, companies committed to sustainability outperformed industry averages by 15 percent from May through November 2008.9

The Good Company Index that we created to measure the worthiness of the Fortune 100 reinforces these findings. As we’ll discuss in greater detail in Chapter 6, we decided to see how Fortune 100 companies in the same industry with different Good Company Index scores performed in the stock market. We found that companies with higher Good Company Index scores (worthier companies, in other words), did better in the stock market over the last year, the last three years, and the last five years than their industry match with a lower Good Company Index score.

In sum, then, there is much compelling evidence that good companies (and their owners) enjoy higher share-price appreciation than their less-good counterparts, and that goodness actually predicts future stock market performance.

Beyond studies of stock returns, other research indicates that companies can do well by doing good. A 2009 report by economists Scott J. Callan and Janet M. Thomas examined 441 large U.S. firms and found corporate social responsibility—referred to as corporate social performance in scholarly circles—helps rather than hinders financial success. “Empirical evidence of a positive [corporate social performance]-[corporate financial performance] relationship indicates that firms need not view social responsibility and profitability as competing goals,” Callan and Thomas conclude. “In fact, firms might measurably benefit from their socially responsible decisions, if these decisions are recognized and rewarded by relevant stakeholders. This recognition might take the form of stronger consumer demand or higher worker productivity, which in turn would yield to the firm a stronger financial performance.”10

There is another benefit from being a good company: it increases the probability of long-term survival. This is more significant than it might seem at first blush. In his summary of a study done by Shell Company on corporate longevity, Arie de Geus reports that “the average life expectancy of a multinational corporation—Fortune 500 or its equivalent—is between 40 and 50 years…. Human beings have learned to survive, on average, for 75 years or more, but there are very few companies that are that old and flourishing.”11

De Geus concludes that the essential attribute of these “living organizations” is that they are a “community of humans.”12 “Like all organisms, the living company exists primarily … to fulfill its potential and to become as great as it can be.”13 This suggests that while companies need to be profitable to survive and thrive, existing purely for the purpose of making profits is an insufficient purpose—one that, in and of itself, is unlikely to foster corporate longevity.

In another ambitious study of long-lived corporations, Danny Miller and Isabelle LeBreton-Miller conclude that such corporations tended to be disproportionately family controlled, and that they share three core philosophies:

• Ownership Philosophy—owners are stewards (not traders)

• Business Philosophy—they are driven by a substantive mission (not quick financial results)

• Social Philosophy—they have shared values and foster lasting relationships (not one-shot transactions)

The “substantive mission” at the heart of long-lasting corporations is akin to the worthy purpose we see as key to good companies. Miller and LeBreton-Miller write:

Substantive missions are not concocted by some strategic planner, nor are they financially driven. They flow from values residing in the bellies of family proprietors. And like all bulwarks, they are immovable. Although missions are manifested in objectives such as making a superb product, pioneering technologies, or establishing an effective brand, they are more fundamental than that. Their ultimate purpose is to make a difference in how people live, in social or scientific progress, even in the joyfulness of life.

Miller and LeBreton-Miller give the example of a well-known tire maker founded in 1888: “The Michelins had a mission to transform travel into a safer, happier experience.”14

Similarly, in his analysis of firms that are profitable over the long term (which is, in some cases, hundreds of years), Joseph Bragdon concludes that these companies operate as, “an organic living system whose defining elements are living assets; that it exists within the larger web of life, on which it utterly depends; and that its ‘reason for being’ is to serve humanity in sustainable ways that don’t harm the web.”15

Consider, for example, Finland-based Stora Enso. The maker of paper, packaging, and wood products is “the world’s oldest company,” writes Bragdon, “It has survived for 700-plus years because from the beginning, its owners (initially a religious diocese) and managers cared about employees and the community in which it operated. Stora Enso’s governance became decentralized in the mid-fourteenth century due to a royal charter and a mining statue that dispersed power among a group of master miners and established fair wages and work sequencing. Since then the company has survived and grown, thanks to an open, tolerant culture that learns and adapts from the bottom up.”16

Research into the factors behind the survival of firms with initial public stock offerings also points to the value of worthiness. A team of scholars led by University of Southern California management professor Theresa Welbourne discovered that investments in human resources are the strongest predictors of the survival of firms five years after an IPO.17 The HR factors Welbourne and her team investigated included the degree to which the firm valued its employees vis-à-vis other assets, seen partly in whether a company has an HR officer as a senior executive. The researchers also examined the distribution of rewards, including whether stock options or profits were shared with all employees.

People management factors proved more significant to a company’s long-term health than a host of other indicators, such as net profit per share at the time of the IPO, industry type, and the risk of legal proceedings against the firm.18

Interestingly, Welbourne and her team also found that human-resource investments had a negative effect on the initial IPO “going out” stock price. This suggests that investors have tended to view HR as a distraction and employees as primarily a cost rather than an asset.

On the contrary, prioritizing people management is critical for sustainable success, Welbourne says.

“The reason HR factors had a positive effect on longer-term performance was due to their effects on what we call ‘structural cohesion,’” Welbourne writes. “Structural cohesion is an employee-generated synergy—essentially a close-knit, high-energy culture—that propels the company forward.”19

From a variety of perspectives, then, the data is clear: companies survive and can do well by doing good.

Benefits to Goodness Through and Through

The evidence summarized above confirms there is a long-term payoff to taking the high road to profitability. To be sure, the low road—characterized by questionable ethics, unscrupulous behavior, plundering the environment, and unvarnished greed—also can be extremely lucrative. The record profits that Goldman Sachs earned in the wake of betting against its own customers is a case in point.20 But there are also signs that the tide is turning and that companies are going to find the low road to profitability more challenging in the future.

A more ethical approach to economic choices has been building steam over the past decade, and the Great Recession did not sidetrack the trend. Although people might have been tempted to focus narrowly on selfish needs like rock-bottom prices and rapid stock returns, by and large they opted for a higher road. Nearly six in ten global consumers polled in 2009 said a company or brand earned their business during the recession because it has been doing its part to support good causes.21 And, as mentioned in Chapter 1, nearly three out of four Americans surveyed in 2010 said they are more likely to give their business to a company that has fair prices and supports a good cause than to a company that provides deep discounts but does not contribute to good causes.22

Mitch Markson, Edelman’s chief creative officer, argues that companies with a commitment to positive social change will get a boost from consumers, while indifferent or harmful firms will be punished. “People today are more passionately involved and supportive than ever, yet more demanding and unforgiving, as well,” Markson says.23

Edelman’s annual surveys on the importance of a good company purpose back up the point. In 2010, 62 percent of consumers globally said they would help a brand promote its products if there was a good cause behind it, up from 59 percent in 2009 and 53 percent in 2008.24 The 2010 report also found that 37 percent of Americans would punish a company that doesn’t actively support a good cause by sharing negative opinions and experiences, while 47 percent would not invest in such a company.25 Edelman’s data is part of a wide range of evidence showing the growing benefits of goodness—and the dangers of choosing otherwise.

Consumers, for instance, are holding companies to a high green standard. A 2009 study by communications services firm WPP and consulting firm Esty Environmental Partners found that at least 77 percent of consumers in all seven countries studied say it’s somewhat or very important for companies to be green. The most important step a company can take to demonstrate its “greenness” is to reduce the amount of toxic or other dangerous substances in its products and business processes, according to the report. But consumers expect much more.

“While reducing toxics heads the list of consumer priorities the data also shows that the public holds companies accountable for good environmental behavior across the board,” said Dan Esty, chairman of Esty Environmental Partners. “Consumers expect companies to recycle, use energy efficiently, reduce packaging, and pursue green innovation. So to gain loyalty, a company’s environmental strategy must be comprehensive.”26

People aren’t just talking about green. They are backing up their ecological words with their wallets. In the WPP-Esty Environmental Partners study, consumers in both developed and emerging economies indicated they plan to spend more money on green products in the coming year.27 And in keeping with the Accenture report on technology products referenced in Chapter 3, consumers in developing countries were particularly keen on going green. Seventy-three percent of Chinese consumers said they will spend more on environmentally friendly products, along with 78 percent of Indians and 73 percent of Brazilians.28

Environmental stewardship also is an increasingly vital factor to shoppers in the developed world. In the United Kingdom, for example, average household spending on products and services that combat global warming has risen in the past decade. Spending on such items as green transport, energy efficiency, and renewable energy increased from less than $37 annually in 1999 to nearly $495 in 2008.29

And in the United States, organic foods—which tend to be earth-friendly because organic farming methods avoid the release of synthetic pesticides into the environment—have become mainstream. One-fourth of U.S. adult shoppers frequently purchase certified organic food or beverage products, and one-third are usually willing to pay more for organic foods, according to a 2009 report by market researcher Packaged Facts.30

That report discussed a broader category of “ethical” consumer products, referring to items that are green, natural, organic, humane, or the result of fair trade. Packaged Facts said the U.S. market for ethical products had grown annually in the high single- to low double-digits over the previous five years. And it predicted the growth rate would persist despite the recession, with the market approaching $62 billion in 2014 up from a projected $38 billion in 2009.

“Our survey indicates that more shoppers understand the environmental, social, and economic implications of their choices,” said Don Montuori, publisher of Packaged Facts. “The result is a sizeable number of consumers who will purchase typically more expensive ethical products even in economically challenging times.”31

Other evidence that consumers will reward good companies and punish bad ones comes from a 2009 paper by researchers Remi Trudel and June Cotte.32 Trudel and Cotte conducted a series of experiments about hypothetical coffee and cotton products, asking people about the prices they would pay for items from companies with a range of ethical practices. Customers will pay a premium for ethically produced goods and demand a lower price for products from companies that are not seen as ethical, the researchers found.

“Stay away from goods that are known by consumers to be unethically produced or pay the price (that is, know that your consumers will not pay the price),” Trudel and Cotte warn.33

In recent years, the phrase ethical products has become one of the main ways researchers, marketers, and the public at large talk about sustainability and social responsibility. The term and the trend speak to the way people increasingly connect all the facets of company goodness into a coherent whole. More and more, sustainability, corporate citizenship, and social responsibility amount to a holistic concept encompassing worthiness as an employer, a seller, and a steward of people and the planet.

Signs that consumers are calling for a comprehensive approach to good corporate citizenship surfaced in a 2007 report by public-relations firm Fleishman-Hillard and the National Consumers League advocacy group. It found that U.S. adults want more from firms than the charitable giving they’ve done for years.

Consistently, consumers define the meaning of and expectations for corporate social responsibility in ways that go beyond just traditional charitable contributions and philanthropic giving…. Consumers expect companies to contribute to their communities by volunteering time and effort to local activities, getting involved in community events in nonfinancial ways, providing jobs, and treating their employees well. Companies can no longer assume that donations alone, however much they may be appreciated, can sustain a positive reputation for social responsibility.34

Consumers don’t expect complete purity when it comes to sustainability. Trudel and Cotte found that the price premium for T-shirts made with 100 percent organic cotton wasn’t very different from the premium given to shirts with 25 percent organic cotton. On the other hand, examples of outright badness will cost companies dearly, the researchers discovered. Information about unethical behavior—such as the use of child labor or heavy use of a pesticide—led to a price penalty that was bigger than the price premium given to companies with ethical practices. In other words, “consumers will punish the producer of unethically produced goods to a greater extent than they will reward a company that offers ethically produced products.”35

Trudel and Cotte’s work suggests that (at least as of 2009) there may be a threshold at which diminishing marginal returns set in when it comes to goodness (e.g., firms enjoy smaller incremental gains from additional investments in sustainability). Our prediction is that as time passes, consumers will push this threshold to a higher and higher level. But putting this prediction aside, what Trudel and Cotte’s analysis makes clear is that firms guilty of serious offenses will reap customers’ wrath.

It’s not just consumers who seek to do business with companies well-rounded in their worthiness. Workers also want to be part of a company that is good through and through. As mentioned in Chapter 1, 56 percent of people globally want a job that allows them to give back to society versus 44 percent who value personal achievement more.36 What’s more, a 2009 study by staffing firm Randstad asked U.S. workers about traits of their ideal employer and found that 80 percent mentioned both “delivers on its promise to customers” and “cares about their employees as much as their customers.” Those answers tied for the top spot, and the responses for both were up from 65 percent and 66 percent, respectively, the previous year.37 In other words, workers increasingly are drawn to companies that do right by both customers and employees.

Investors too are gravitating toward overall goodness. As mentioned in Chapter 1, the value of assets linked to the Dow Jones Sustainability Indexes—which grade companies on criteria including customer relations, corporate codes of conduct, labor practices, and environmental impact—grew from about $1.5 billion at the end of 2000 to more than $8 billion at the close of 2009.38

According to Time magazine, the number of socially responsible investment mutual funds, which generally avoid buying shares of companies that profit from such things as tobacco, oil, or child labor, grew from 55 in 1995 to about 260 in 2009. Time estimated these funds managed approximately 11 percent of all the money invested in U.S. financial markets in 2009—an estimated $2.7 trillion.39

It stands to reason that consumers, workers, and investors clamoring to do business with thoroughly good companies would allow such firms to succeed. By practicing enlightened self-interest, worthy companies would seem likely to woo loyal customers, attract and inspire top-notch talent, and command greater amounts of investment capital.

And in fact, evidence supports such a conclusion. The power of integrated goodness can be seen in a 2008 study by consulting company Watson Wyatt Worldwide (now Towers Watson) and public-relations firm Brodeur Partners. That report found that companies that closely mesh their external brand with their employee experience outperform peers. It concluded that tight alignment between a company’s external message and its employment “deal”—the rewards and experience a firm offers to workers—leads to increased employee engagement and retention, a superior customer experience, and a 15 percent higher market premium compared to industry peers.40

The result is at once striking and intuitive. As the study notes, employees play a key role in “delivering the brand promise to customers” just as company brand and reputation can be crucial in attracting and retaining talent.41

Another example that points to the growing imperative of doing well by doing good that may take some readers by surprise is Walmart. Walmart has been far from perfect in the past decade or so, especially in the area of people management. Its minimal fringe benefits arguably have burdened communities, as employees have had to rely on public health-care systems; its low-wage strategy may have cost the company more through high attrition than the higher wages paid by rival Costco; and it has displayed callousness toward workers.42

Still, Walmart has taken a number of steps to treat workers better, including improved health-care benefits.43 As mentioned in Chapter 3, Walmart has taken a leadership role in the environmental arena. And it portrays itself as a steward of hardworking, lower-income consumers. Although it is debatable whether the company’s overall effect—taking into consideration its massive use of overseas manufacturers—has harmed or hurt lower-income Americans, the company’s low prices undoubtedly eased some of the difficulties of the recession for many customers.

In the wake of these efforts, Walmart has seen its reputation and bottom line improve. The company was ranked as the seventh most green brand in the United States in the 2009 study by WPP and Esty Environmental Partners.44 And Walmart’s reputation improved more than any other company between 2007 and 2008, according to research firm Harris Interactive.45

The bottom line is that the public is showing greater and greater unwillingness to keep company with less-than-good companies. Harris found in a 2009 study that 90 percent of Americans said they give some consideration to sustainable business practices when purchasing a company’s products and services—with nearly 30 percent saying they consider sustainability “a great deal” or “a lot.”46

Harris defined sustainable business practices comprehensively as “a company’s positive impact on society and the environment through its operations, products, or services and through its interaction with key stakeholders such as employees, customers, investors, communities, and suppliers.” Given this definition, Americans generally aren’t pleased with what they see. All but 2 percent of those polled by Harris said it is at least somewhat important for corporations to evolve to more sustainable business practices. Fifty-seven percent said corporations are not adequately evolving to more sustainable business practices.47 And, as mentioned in Chapter 4, a large majority told Harris that regulation of businesses is in order.48

Overall, Harris found that a record number of Americans—88 percent—said the reputation of corporate America was “not good” or “terrible” in 2008. The figure improved slightly to 81 percent in 2009.49

To be sure, companies can go too far in a quest to be good to all stakeholders. Overly generous salaries, excessive charitable donations, and extreme efforts to reduce carbon footprints can bankrupt a firm or prevent it from devoting enough resources to research and development, marketing, and other crucial functions. Balance remains important.

It’s also possible that Scrooge-like companies that look out for a narrow group of shareholders or stakeholders will be able to keep making profits in the years ahead. There remains a portion of the public that for ideological or other reasons does not demand much worthiness on the part of the firms in their lives.

But in the emerging era of goodness, companies would do well to err on the side of acting as Santa rather than Scrooge.

Consider this finding from Edelman’s 2010 “good purpose” study: 86 percent of global consumers believe that business needs to place at least equal weight on society’s interests as on those of business.50

That statistic points to the growing significance of a genuine commitment to goodness. So do the findings of a 2009 poll commissioned by Time magazine. According to the survey, 38 percent of American adults—some 86 million people—reported taking a number of socially conscious actions in 2009, including buying green products and goods from companies they thought had responsible values.51

In announcing the arrival of “the ethical consumer,” Time noted: “We are starting to put our money where our ideals are.”52

If companies want to succeed in this ethical age, they had better live up to those ideals.

CHAPTER FIVE SUMMARY

The best available hard-nosed evidence consistently shows that companies are doing well by doing good. Although much of this evidence is based on large, publicly traded U.S. firms, the convergence of economic, social, and political factors outlined in Chapters 1 to 4 points to the growing imperative for all organizations—private or public, large or small—to become thoroughly worthy.

Doing Well by Doing Good

• Good companies tend to outperform less worthy companies in the stock market.

• Companies that are a “community of humans,” have a “substantive mission,” and “exist within the larger web of life” are more likely to survive over the long run than companies that do not possess these attributes.

• In sum, companies survive and can do well by doing good.

Benefits of Goodness Through and Through

• A growing body of evidence indicates that companies with a commitment to positive social change will get a boost from consumers, while indifferent or harmful firms will be punished.

• People increasingly connect all the facets of company goodness into a coherent whole—more and more, sustainability, corporate citizenship, and social responsibility amount to a holistic concept encompassing worthiness as an employer, a seller, and a steward of people and the planet.

• Consumers don’t expect complete purity when it comes to sustainability, but they want more from firms than just charitable giving.

• Employees and investors also are gravitating toward overall goodness.

• The public is increasingly unwilling to keep company with less-than-good companies.