7

Ways to Get More and Better Ideas

WHEN AN IDEA SYSTEM is launched, rarely is there a shortage of ideas. Front-line employees are already aware of many problems and opportunities that they have never had an easy way to correct before. Here, for example, are some of the early ideas at Big Y Foods:

![]() (Bakery) Customers often ask if we sell the garlic butter we use to make garlic bread. I suggest we sell it in eight-ounce containers.

(Bakery) Customers often ask if we sell the garlic butter we use to make garlic bread. I suggest we sell it in eight-ounce containers.

![]() (Checkout) The “tender” key for totaling an order is very close to the “clear sale” key on the touch screen cash registers. We often hit the “clear sale” key by accident instead, and delete the last sale. Have the IT department place these two keys farther apart.

(Checkout) The “tender” key for totaling an order is very close to the “clear sale” key on the touch screen cash registers. We often hit the “clear sale” key by accident instead, and delete the last sale. Have the IT department place these two keys farther apart.

![]() (Produce) Currently, stores call a special number to leave a message on an answering machine to report over/short deliveries in produce to be corrected in the next day’s delivery. Since no one ever physically answers this phone, why is the answering machine set to pick up after nine rings, making every store’s personnel wait thirty seconds unnecessarily every day?

(Produce) Currently, stores call a special number to leave a message on an answering machine to report over/short deliveries in produce to be corrected in the next day’s delivery. Since no one ever physically answers this phone, why is the answering machine set to pick up after nine rings, making every store’s personnel wait thirty seconds unnecessarily every day?

![]() (Deli Counter) Why does it take nine keystrokes to key in a slice of pizza in the deli section? Please fix.

(Deli Counter) Why does it take nine keystrokes to key in a slice of pizza in the deli section? Please fix.

![]() (Meat Section) Put a mirror above the partition between the service counter and the back room where we cut the meat so we don’t have to put down our work every three minutes to come out and see if a customer is waiting.

(Meat Section) Put a mirror above the partition between the service counter and the back room where we cut the meat so we don’t have to put down our work every three minutes to come out and see if a customer is waiting.

![]() (Groceries) We currently sell tubes of flavored ice unfrozen, for people to take home and freeze for their children. In the summer, why not put some in the freezer for impulse buys?

(Groceries) We currently sell tubes of flavored ice unfrozen, for people to take home and freeze for their children. In the summer, why not put some in the freezer for impulse buys?

These are all good ideas that were quickly implemented. But notice how they are also commonsense responses to problems that have made employees’ jobs harder or are straightforward responses to repeated customer requests. Such ideas usually get an idea process off to a good start. But once the obvious problems have been addressed, the rate at which ideas come in typically slows dramatically. The remedy is to provide ongoing training and education to help your front-line people continually generate new types of ideas. This chapter is a primer of easy-to-use “street-smart” techniques to keep ideas coming in.

PROBLEM FINDING

In its most basic form, creativity can be divided into two parts: problem finding and problem solving. Historically, most organizations have focused on problem solving. This is only natural, because most organizations struggle to keep up with the onslaught of obvious problems that pop up in the normal course of daily work. Why would they go looking for more? A huge industry has built up around problem solving, and many books, tools, and training programs are available for help in this area.

A good idea system significantly multiplies an organization’s problem-solving capacity, so it burns through the obvious problems faster than they come in. To keep improving, it has to get better at problem finding. This effort has two components: (1) developing employees’ problem-finding skills and (2) creating organizational mechanisms that bring more problems to the surface.

Problem finding is a matter of perspective. So a quick and easy way to enhance your employees’ problem-finding abilities is to expose them to fresh perspectives on how the organization can be improved. These alternative perspectives will cause them to see problems and opportunities that they would not have seen otherwise. Two methods to do this are idea activators and idea mining.

Idea Activators

Idea activators are short training or educational modules that teach people new techniques or give them new perspectives on their work that will trigger more ideas. Depending on the nature of the information to be imparted, these modules can be anything from a ten-minute talk to a formal classroom training session of several hours. To see how idea activators work, let us look at how Subaru Indiana Automotive (SIA) used a series of carefully targeted activators to reach the very ambitious goal mentioned briefly in Chapter 3.

In 2002, Fuji Heavy Industries, SIA’s Japanese corporate parent, gave it the goal of becoming “zero landfill” by 2006. SIA’s leadership team knew that to reach this goal in a cost-effective manner, they had to involve their front-line associates. They were the ones who first handled materials (such as packaging, used solvent, and steel scrap) after they had served their intended purpose and become waste.

However, the leadership team also knew that simply asking associates for their “green” ideas would not be enough. Most people have a fairly limited understanding of how to reduce an organization’s environmental impact. For example, everyone knows about recycling, but most recycling offers only limited environmental advantages and is generally not cost effective. So SIA set out to increase its people’s ability to spot green improvement opportunities by using idea activators. These activators introduced them to simple concepts that the company thought would spark large numbers of small ideas to eliminate landfill waste.

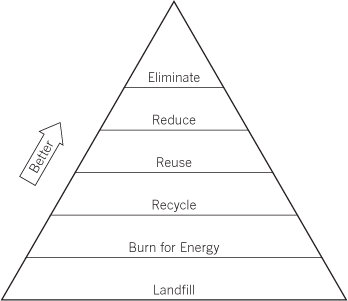

The Three Rs. SIA began with a brief orientation session on the Three Rs: reduce, reuse, recycle. The Three Rs are the central components of what is often referred to as the “waste management hierarchy” (see Figure 7.1). Starting from the bottom, this hierarchy ranks the different kinds of environmental actions in increasing order of environmental benefit:

![]() Burning material for energy is better than sending it to a landfill.

Burning material for energy is better than sending it to a landfill.

![]() Recycling it is better than burning it.

Recycling it is better than burning it.

![]() Reusing material is better than recycling it.

Reusing material is better than recycling it.

![]() Reducing the amount needed is better than reusing it.

Reducing the amount needed is better than reusing it.

![]() Eliminating the need for material is better than reducing it.

Eliminating the need for material is better than reducing it.

The Three Rs framework was a good initial idea activator for SIA’s purpose, because it was easy to remember and got people to think of ideas beyond simple recycling. Employees were taught to try to move what was done with waste materials further up the hierarchy, because this produced both greater environmental benefits and more cost savings.

One set of ideas, for example, moved the packaging for engine components from recycling to reuse. These components came from a Japanese supplier in large shipping containers, packed tightly in specially contoured protective Styrofoam blocks. Formerly, as employees unpacked these parts, they would put large amounts of Styrofoam into recycling bins. Recycling Styrofoam is expensive, as its low density increases handling and shipping costs, and it requires more processing and energy than most other polymers. But after Three R training, an employee team began to wonder whether it wouldn’t be feasible to reuse this packaging. Since the empty shipping containers were already being sent back to the supplier, why couldn’t they be repacked with the used Styrofoam so it could be reused by the supplier for a future shipment?

After analyzing the feasibility and costs of this, the team discovered that the idea would actually be profitable, and it quickly led to other ideas to return packaging materials to that supplier for reuse. Eventually, some eighty different kinds of plastic caps, metal clips, cardboard spacers, and various other packing materials were being returned to Japan for an annual savings of more than $3 million. When the Styrofoam packaging material is considered no longer suitable for reuse, the Japanese supplier melts it down and reuses the polymer to make new packaging material.

Other ideas, some extremely simple, reduced the company’s usage of materials. One, for example, was to have parts arrive in open-topped boxes. Since they were delivered on wrapped pallets anyway, the tops weren’t needed. This idea not only saved cardboard but also meant workers no longer had to use box cutters to open the boxes—hence, a safety and productivity improvement as well.

Dumpster Diving. If nothing was to be thrown away, everything put into the dumpsters had to be eliminated—recycled, reused, or not generated in the first place. Even the dumpsters themselves had to go. To this end, SIA developed another activator called “dumpster diving.” Dumpster-diving teams overturned the dumpsters in their areas, spilling their contents onto the floor where they were sifted and sorted by source and type. Then the teams came up with ideas to deal with each type of waste using the Three Rs.

The effectiveness of this tactic is illustrated in the case of the dumpster that was located near the robotic welders used to assemble the car bodies. The dive team quickly realized that the “dirt” in the dumpster was actually the remnants of sparks generated during the welding process. These sparks are small particles of welding slag, which includes copper oxide blown off the copper welding tips by the arcing of the high-amperage electric current used to fuse the steel together. If zero landfill were the goal, sending the floor sweepings to the landfill would no longer be an option. After some searching, SIA found a company in Spain that could process the slag to recover the copper.

While processing the welding slag kept it out of the landfill, it was expensive to ship it to Spain (and the shipping added to the company’s carbon footprint). So SIA set out to reduce the amount of sparks created in the welding process. Because sparks are caused by arcing between the copper welding tips and the steel, the better the fit between the tip and the steel, the fewer the sparks that are generated. A new tip of the proper shape sparks very little. But with use, the hot copper welding tips soften and deform, degrading the fit and creating more sparks. Because it is expensive and disruptive to replace the copper tips as they start to deform, standard practice is to increase the amperage on the welder every two hours to assure a good weld. The extra power produces even more sparks and heat, creating more tip deformation, which requires even more amperage, and so on. Now, instead of turning up the electricity when the tips deform, a special device mounted on each welder quickly machines them back to the optimal shape. The result—fewer sparks, less electricity used, and a 73 percent reduction in the number of welding tips consumed.

Compressed Air. The largest consumers of electricity at SIA were the air compressors. Compressed air was used extensively throughout the facility in a wide range of manufacturing processes. To reduce its consumption, SIA developed an idea activator that showed employees the high environmental and financial cost of generating compressed air and provided them with a number of clever tips on how to identify opportunities to cut its usage. This information resulted in thousands of ideas throughout the facility to plug air leaks and to replace O-rings in leaking pneumatic equipment, to improve maintenance regimes on air-powered tools and air cylinders, and to install shut-off valves for areas that did not need compressed air all the time. Here are some of the more creative ideas:

![]() Turning the plantwide compressed air level down from ninety-two pounds per square inch (psi) to eighty-seven, because the last few psi require a disproportionate amount of energy to generate and were not necessary—especially with the better-maintained pneumatic equipment

Turning the plantwide compressed air level down from ninety-two pounds per square inch (psi) to eighty-seven, because the last few psi require a disproportionate amount of energy to generate and were not necessary—especially with the better-maintained pneumatic equipment

![]() Using a sensitive sound meter (when the facility is not operating and quiet) attached to a pole to listen to compressed air pipe joints high up near the ceiling for even tiny air leaks that humans couldn’t hear

Using a sensitive sound meter (when the facility is not operating and quiet) attached to a pole to listen to compressed air pipe joints high up near the ceiling for even tiny air leaks that humans couldn’t hear

![]() Connecting two areas of the plant that had separate compressed air systems with an air pipe so that when combined demand was low enough, the two areas could share a single set of compressors

Connecting two areas of the plant that had separate compressed air systems with an air pipe so that when combined demand was low enough, the two areas could share a single set of compressors

Cumulatively, the resulting front-line ideas to save compressed air cut the amount of electricity needed to generate compressed air in half, and SIA was able to take two of its four large air compressors offline.

Recycling Versus Downcycling. Another idea activator taught the difference between recycling and downcycling. Downcycling occurs when the method of recycling reduces the value or quality of the material. In most plastic recycling, for example, a wide assortment of different types and colors of plastics is melted down into an amorphous polymer blend useful only for low-value applications such as parking bumpers and plastic boards. Most “recycling” is actually downcycling. Whereas downcycling degrades the material, true recycling maintains its original physical characteristics and quality.

Armed with this new understanding, employees generated hundreds of ideas to change processes in order to avoid downcycling whenever possible. For example, a large number of ideas involved getting suppliers of different parts to use uncolored plastic of a standardized grade for packaging, so the different parts could be recycled together without degrading the value of the polymer.

SIA’s green idea activators enabled its front-line employees to come up with large numbers of ideas without the need for disruptive and expensive formal training programs. Most of the activators were short enough to be delivered to work teams at their regular stand-up preshift team meetings. In the end, SIA sent its last waste shipment to a landfill in May 2004, two years ahead of its deadline, having also reduced its annual operating costs by millions of dollars.

Like at SIA, the specific sequence of idea activator training sessions that you need to develop will depend on your organization and its strategic goals. Some of these activators may be generic improvement tools that are already widely used to identify and solve common problems. By way of example, many lean tools—such as 5S (good housekeeping), poka-yoke (error-proofing), process charting, and value stream mapping—are reliable triggers for a large number of ideas. For instance, Bumrungrad Hospital in Bangkok, Thailand, one of the leading hospitals in the world, has radically reduced or almost entirely eliminated many kinds of medical errors through extensive application of poka-yoke principles at every stage of the health care delivery value stream.

Idea activators do not have to address only the major goals of top management. They can address smaller targets of opportunity as they are identified at the front-line level. For example, in a U.K. financial services company, many ideas requested the IT department to write Excel macros to save office workers’ time on repetitive tasks. After seeing a number of these ideas over a few months, a middle manager suggested providing a quick idea activator on how to create Excel macros, so staff members could do it themselves. This certainly saved the IT function time, but it also triggered many ideas from people who could now see more applications for macros and also easily create them themselves.

Idea Mining

Many ideas have novel perspectives embedded in them. These perspectives are usually implicit, but if drawn out, they have the potential to trigger more ideas. The process of digging out these implicit novel perspectives is what we call idea mining.

We once witnessed a senior manager at a European insurance company put the concept to use immediately after a short training session on idea mining. Sitting in the back of an idea meeting in one of the company’s small animal pet insurance call centers, we were observing the employees discuss problems and brainstorm ideas. One problem on their board was that customers were frequently calling the department for help with equine policies. The equine insurance division was in a different part of the country, and there was no way for the representatives to transfer these calls. Such calls were occurring some ninety times per week, and each wrong number took two or three minutes to deal with. The representative had to apologize, explain to the customer that he or she had called a wrong number and that there was no way the call could be transferred, wait for the customer to get a pencil and a notepad, provide the customer with the correct number, and perform any other needed service recovery. Two minutes per call, ninety times per week, meant that the problem was wasting about three hours per week.

One employee pointed out that the reason for all the wrong numbers was that the company’s Yellow Page ad was confusing. The ad contained many phone numbers, and its graphics and layout made it easy for customers to call the wrong number. “I’ll let the marketing department know, as they are about to place the new ads in this year’s Yellow Pages,” their manager said, and then began to move onto the next idea.

“Wait!” the senior manager piped up from the back. “Before you move on, let’s make a new rule. Every time a customer is confused, let’s write down the source of confusion on the idea board and see if we can fix the problem. When customers are confused, it is frustrating for them and wastes both their time and ours.” He had noticed that the idea embodied a fresh perspective that the group could use to come up with new types of ideas to improve customer service. By drawing this new perspective out and making customer confusion a “problem flag” for the group, the senior manager made this single idea the seed of many more.

Not long afterward, we shared this example in a training session at a U.S. health insurance company. On our next visit, the idea system manager proudly remarked that the company had created its own problem flag. “Every time a customer calls, write down the reason why. After all, customers do not call just to say hello or to wish us Merry Christmas. They call because something we did, or did not do, made it necessary for them to call.” Think of all the customer service improvements and other ideas that insight led to!

In our seminars, we often use an idea mining exercise to illustrate how easy it is to draw out novel perspectives from a set of ideas. For our explanation of this exercise, we will work with the sheet of “Ideas from the Clarion-Stockholm Bar” given in Table 1.1. For convenience, we reproduce a numbered version of the sheet here as Table 7.1.

We begin by dividing the participants into small groups and asking each group to pick a number between one and eighteen (the number of ideas on the Clarion sheet). We then give them the idea sheet. Each group is asked to find the idea on the sheet that matches the number it picked. (Making participants pick their numbers before giving them the sheet keeps them from “cherry-picking” ideas to work with.)

We then instruct the groups to discuss their chosen ideas and consider the following questions, in order to identify any related ideas and tease out any novel perspectives that are implicit in their chosen idea:

![]() What other ideas does this one suggest?

What other ideas does this one suggest?

![]() What other areas for improvement does this idea suggest?

What other areas for improvement does this idea suggest?

![]() What fresh perspectives about how the organization can be improved does this idea suggest?

What fresh perspectives about how the organization can be improved does this idea suggest?

To show how this works, let us take the example of a group that picked the number six, which corresponds to Tim’s idea:

Whenever the bar introduces a new cocktail, have a tasting for the restaurant staff, just as the restaurant always does when a new menu or menu item is introduced, so servers know what they are selling.

Here are some responses the group might have given for this particular idea:

![]() Whenever the hotel introduces a new product or service, have the staff sample it and have it explained to them so they will be able to answer customer questions about it, will think of recommending it when appropriate, and be better able to sell it when they do.

Whenever the hotel introduces a new product or service, have the staff sample it and have it explained to them so they will be able to answer customer questions about it, will think of recommending it when appropriate, and be better able to sell it when they do.

![]() What other products and services could be sold more effectively if the staff were given the proper training and information about them?

What other products and services could be sold more effectively if the staff were given the proper training and information about them?

![]() This is an example of improving cross-selling. One area (the restaurant) is selling products from another (the bar). In what other ways can we cross-sell products and services within the hotel?

This is an example of improving cross-selling. One area (the restaurant) is selling products from another (the bar). In what other ways can we cross-sell products and services within the hotel?

Although it is impractical to try to mine every idea, and not every idea is worth mining, it is astonishing how many potential perspectives can be extracted from a routine set of ideas. Table 7.2 gives sample responses for just the first five ideas on the Clarion-Stockholm sheet. Moreover, the concept of idea-mining is not difficult to grasp and can easily be demonstrated and taught during a team’s regular idea meeting.

TABLE 7.1 Clarion Hotel Stockholm: Ideas from the bar

The exercise just described is often eye-opening for managers. It shows them the value of targeted idea training and lays to rest the fear that sooner or later employees will run out of ideas. In fact, in our experience, rather than worrying about running out of ideas, after this exercise many managers become more concerned about being overwhelmed by them.

We recommend keeping track of some of the more useful perspectives that come out of idea mining in your meetings. Over time, you can build up a very useful list of broadly applicable questions that can be shared across your organization and used in problem-finding training and in training for new employees. Consider these examples:

TABLE 7.2 Perspectives drawn out of Clarion bar ideas

1. Get maintenance to drill three holes in the floor behind the bar and install pipes so bartenders can drop bottles directly into the recycling bins in the basement:

![]() What other things do bartenders have to leave the bar to fetch or do that could be streamlined or improved?

What other things do bartenders have to leave the bar to fetch or do that could be streamlined or improved?

![]() What aspects of the bartenders’ jobs that are non-value-adding—i.e., that take them away from serving customers—can we eliminate or streamline?

What aspects of the bartenders’ jobs that are non-value-adding—i.e., that take them away from serving customers—can we eliminate or streamline?

![]() Are there other places in the hotel where we can make recycling easier?

Are there other places in the hotel where we can make recycling easier?

![]() Can we reduce the amount of bottles and cans we use in the first place?

Can we reduce the amount of bottles and cans we use in the first place?

2. When things are slow in the bar, mix drinks at the tables so the guests get a show:

![]() What other things can we do to make our service flashy and entertaining?

What other things can we do to make our service flashy and entertaining?

![]() What other things could we do at the tables that would be different and interesting?

What other things could we do at the tables that would be different and interesting?

![]() In what other ways could we use extra bartending capacity when things get slow?

In what other ways could we use extra bartending capacity when things get slow?

3. Many customers ask if we serve afternoon tea. Currently, there is no hotel in the entire south of Stockholm that does. I suggest we start one:

![]() What other drinks and foods are customers asking about, and can we provide these?

What other drinks and foods are customers asking about, and can we provide these?

![]() Afternoon tea is a British concept. What other national or ethnic traditions can we cater to?

Afternoon tea is a British concept. What other national or ethnic traditions can we cater to?

![]() What other things are offered in bars and hotels that we don’t offer?

What other things are offered in bars and hotels that we don’t offer?

4. Have an organic cocktail. Customers often ask for them, and we don’t offer one.

![]() What other health needs or lifestyle trends (fair-trade, gluten-free, etc.) do our customers care about?

What other health needs or lifestyle trends (fair-trade, gluten-free, etc.) do our customers care about?

![]() Are there any fashion/political trends we can offer drinks in line with?

Are there any fashion/political trends we can offer drinks in line with?

![]() Ask customers for ideas about drinks we currently don’t offer that they would like.

Ask customers for ideas about drinks we currently don’t offer that they would like.

5. Clarion conference and event sales staff often meet prospective customers in the bar. Give the bar staff information in advance about the prospects so they can be on alert and do something special.

![]() What other potential customers are brought to the bar—birthday parties, weddings, and other events—that it would be useful for the bar staff to know about in advance?

What other potential customers are brought to the bar—birthday parties, weddings, and other events—that it would be useful for the bar staff to know about in advance?

![]() What kinds of special services can bartenders provide, and which will work best?

What kinds of special services can bartenders provide, and which will work best?

![]() What other visitors to the bar may be particularly important to the hotel—VIPs, famous people—and could the bar get a heads-up on those people too?

What other visitors to the bar may be particularly important to the hotel—VIPs, famous people—and could the bar get a heads-up on those people too?

![]() What other hotel services could bar staff be involved in selling?

What other hotel services could bar staff be involved in selling?

![]() Might there be ways to do “something special” for all guests?

Might there be ways to do “something special” for all guests?

![]() Every time a customer asks you for something you or your organization can’t do, ask why it isn’t currently possible and what could be done to make it possible.

Every time a customer asks you for something you or your organization can’t do, ask why it isn’t currently possible and what could be done to make it possible.

![]() Anytime it takes you more than fifteen seconds to find something, ask why.

Anytime it takes you more than fifteen seconds to find something, ask why.

![]() Anytime something comes back to you or your group because it was not done correctly the first time, ask why.

Anytime something comes back to you or your group because it was not done correctly the first time, ask why.

![]() Anytime customers ask questions or seem confused, ask why.

Anytime customers ask questions or seem confused, ask why.

![]() Anytime you realize that you or your coworkers are making mistakes due to a poor process, think what could be changed.

Anytime you realize that you or your coworkers are making mistakes due to a poor process, think what could be changed.

![]() Anytime you throw something out, ask why it is there in the first place (a green perspective).

Anytime you throw something out, ask why it is there in the first place (a green perspective).

The Clarion-Stockholm Hotel also encourages its people to use two additional “digging” techniques that are similar in spirit to idea mining: aggressive listening and thoughtful observation. An example of aggressive listening is that when guests come to reception to check out, the staff will always ask them how their stay was. If a guest has a complaint, the front-desk clerk is careful to get all the details he or she can in order to fully understand what happened. So far, this is no different from most good hotels. The difference comes when a guest responds with simply “Fine” or “OK,” but the clerk can tell that something might be bothersome. The staffer will not simply let it go at that and will politely probe further. When such deeper inquiry is done properly, it becomes a pleasant and sincere conversation while the guest’s receipt is being processed. The guest is sharing a concern or observation with a “friend” that they would normally not mention to a stranger. Think of how many times you have wanted to tell a hotel checkout person about a problem or give a suggestion about how the hotel could do better, but held back because you felt the staffer was not really interested.

The Clarion-Stockholm also encourages its employees to observe customers closely to notice subtler problems and opportunities that customers may not formally articulate. One astute observation, for example, came from a server in the dining room. She noticed that many customers left their reading glasses at home and had trouble reading the menu. Her suggestion: have a box with various strengths of reading glasses to lend to diners who need them.

The increased thoughtfulness about the guest experience results in some unique touches at the hotel. For example, one day a guest arrived in a panic. He was about to lead a workshop, the battery on his laptop computer was almost dead, and he had forgotten to bring his charger. A member of the front desk staff scoured the hotel to find one that would work. Once the guest’s problem was solved, the staffer submitted an idea: purchase spare chargers for the most popular laptop computers for guests with emergencies, and keep these chargers on hand in the hotel’s two business centers.

CREATING A PROBLEM-SENSITIVE ORGANIZATION

Our focus so far in this chapter has been on ways to enhance individual problem sensitivity. This section looks at how to use policies and processes to increase an organization’s problem sensitivity.

Graniterock is a Malcolm Baldrige National Quality Award–winning supplier of rock, sand, gravel, concrete, asphalt, and other materials to the construction industry south of San Francisco, California. In 1989, CEO Bruce Woolpert introduced his “short-pay” policy, which states that “If you [the customer] are not satisfied, … don’t pay us.” If a customer is not satisfied with some aspect of the products or services he receives from Graniterock, he simply deletes the relevant charge on its invoice and pays the rest.

According to Woolpert, organizations are very skilled at building thick “defensive crusts” that isolate them from customer complaints. The short-pay policy was put in place to cut through this crust by making sure that customers voiced their problems and that the organization acted on them.

Before putting the policy in place, Woolpert made sure his organization was ready for it. As he put it to us:

When we introduced the short-pay policy, I was very careful to go around and make sure that people felt—in their hearts and in their minds—that we really should not be paid if we didn’t make someone happy. The reason I did this was that I wasn’t sure what the reaction would be to a customer actually doing a short-pay … because it could seem that doing a short-pay is a confrontational thing, but it’s not. … We made sure people felt that it was really unethical to make people pay for something for which they really didn’t receive good value.

Once the policy was introduced, the company promoted it heavily; and in the first year some six hundred short-pays cost the company the equivalent of 2.3 percent of its sales. While this would be a major sacrifice for any company, it was even more so for Graniterock, because the gravel and concrete industry operates on particularly low margins. Today, with a lot of problem solving under its belt, the cost of Graniterock’s short-pay policy is under 0.2 percent of sales, far less than what most companies set aside for returns.

When a customer short-pays, Graniterock goes through a process to understand the incident and fix the problem. The customer is called immediately, given an apology, and assured that the short-pay has already been taken off the bill and that the purpose of the call is for Graniterock to learn and improve. Once the customer understands that the call is not about the money, he or she is asked to explain the incident in detail so the Graniterock team can understand exactly why he or she was disappointed. Here are several examples of improvements the short-pay policy has triggered:

![]() The biggest problem the short-pay system flagged early on was poor on-time delivery performance. Part of the reason was that the company didn’t have a good dispatching system—the dispatching office used large poster-sized sheets of paper on the wall to write down orders as they came in, and highlighter pens to track the status of the loads throughout the day. On busy days, it was hard for dispatchers to keep track of all of the information coming in, and deliveries would inevitably fall behind. The improvement team searched for software that could help. Today, there are plenty of options, but back in 1989 the company had to create its own dispatching software by adapting software designed for other industries.

The biggest problem the short-pay system flagged early on was poor on-time delivery performance. Part of the reason was that the company didn’t have a good dispatching system—the dispatching office used large poster-sized sheets of paper on the wall to write down orders as they came in, and highlighter pens to track the status of the loads throughout the day. On busy days, it was hard for dispatchers to keep track of all of the information coming in, and deliveries would inevitably fall behind. The improvement team searched for software that could help. Today, there are plenty of options, but back in 1989 the company had to create its own dispatching software by adapting software designed for other industries.

![]() Another recurring reason for early short-pays (more than fifty in the first year) was problems with colored concrete. Customers would order concrete in different colors, usually red, beige, or some other earth tone. Many contractors short-paid because the color of the concrete was too light or it was blotchy. In these situations, Graniterock was not only hit by the short-pay itself but also often paid for the concrete to be torn up and replaced. At the time, poor color control was the norm in the concrete industry. Every concrete vendor had problems with color consistency, and Graniterock was no different. But for the contractors who had to put up with it, it was a huge problem. Colored concrete is typically used in highly visible places as part of the design concept, such as elaborate patios or swimming pool areas. Although Graniterock had known of the problem, it was only when its teams began visiting the short-paying customer sites that it realized how big the problem actually was. Before the short-pay policy, Graniterock had received only a few complaints about color each year and had never considered the problem to be significant.

Another recurring reason for early short-pays (more than fifty in the first year) was problems with colored concrete. Customers would order concrete in different colors, usually red, beige, or some other earth tone. Many contractors short-paid because the color of the concrete was too light or it was blotchy. In these situations, Graniterock was not only hit by the short-pay itself but also often paid for the concrete to be torn up and replaced. At the time, poor color control was the norm in the concrete industry. Every concrete vendor had problems with color consistency, and Graniterock was no different. But for the contractors who had to put up with it, it was a huge problem. Colored concrete is typically used in highly visible places as part of the design concept, such as elaborate patios or swimming pool areas. Although Graniterock had known of the problem, it was only when its teams began visiting the short-paying customer sites that it realized how big the problem actually was. Before the short-pay policy, Graniterock had received only a few complaints about color each year and had never considered the problem to be significant.

Standard industry practice was to add color after the concrete had been loaded in the delivery mixer trucks. The driver would climb up on a loading platform, cut open the heavy bags of coloring powder, and pour the powder into the concrete. The powder then mixed into the concrete on the way to the customer’s site. Before short-pay, when the company had gotten complaints, it had assumed the problem was a dosage error, and someone from the main office would contact the driver to ask how many bags he had put in. Often, the driver couldn’t remember and was simply reminded to be more careful next time. Now that the short-pay policy was making the problem expensive, the Graniterock team began trying to find its root cause in earnest. It turned out that the problem wasn’t the dosages, but clumping. Even when the driver added the correct amount, the dry powder would often clump as it entered the wet concrete and not get blended in thoroughly. So Graniterock found suppliers who could provide the color in liquid form, and the problem was solved.

![]() Another recurring short-pay problem arose from late deliveries to construction sites in new areas whose roads were not yet on the maps. Drivers often spent significant amounts of time driving around looking for the sites. The solution was to use fire department maps, which by regulation had to have all information up-to-date. A collage of fire department maps was put up on a large wall in the dispatching area so drivers could study it and visualize where their construction sites were.

Another recurring short-pay problem arose from late deliveries to construction sites in new areas whose roads were not yet on the maps. Drivers often spent significant amounts of time driving around looking for the sites. The solution was to use fire department maps, which by regulation had to have all information up-to-date. A collage of fire department maps was put up on a large wall in the dispatching area so drivers could study it and visualize where their construction sites were.

![]() Individual short-pays alerted Graniterock to the fact that customers often had unique unstated needs that they simply assumed the company would meet. For example, some customers would state a delivery time but expect the truck to actually arrive fifteen minutes before the concrete was to be poured. Others would expect certain quality and performance additives in every load. These were an added cost, so Graniterock would not include them unless they were specified in the order. But some customers expected these mixes in every load, whether stated or not. After looking into the reasons behind these kinds of short-pays, it turned out that as Graniterock was improving its service, its regular customers were increasingly looking upon it as a partner, and they expected the company to remember their particular requirements. As Woolpert put it, “the short-pay system taught us over time how unique two-thirds of our customers are.”

Individual short-pays alerted Graniterock to the fact that customers often had unique unstated needs that they simply assumed the company would meet. For example, some customers would state a delivery time but expect the truck to actually arrive fifteen minutes before the concrete was to be poured. Others would expect certain quality and performance additives in every load. These were an added cost, so Graniterock would not include them unless they were specified in the order. But some customers expected these mixes in every load, whether stated or not. After looking into the reasons behind these kinds of short-pays, it turned out that as Graniterock was improving its service, its regular customers were increasingly looking upon it as a partner, and they expected the company to remember their particular requirements. As Woolpert put it, “the short-pay system taught us over time how unique two-thirds of our customers are.”

In the beginning of the drive to improve delivery times, Woolpert had made a bet with a friend—the owner of the regional franchise for Domino’s Pizza, a company renowned for its on-time delivery. The bet was about which company would have the better delivery performance over a specified period. The losing company would supply the winner with pizza for all its employees. In the end, Graniterock won in some cities, Domino’s in others, and the bet was declared a wash.

After more than twenty years of operating with short-pay, the company has fixed its more obvious customer-related problems. Today, its short-pay system continues to dig deeper and identify subtler and subtler issues for Graniterock to tackle, giving the company capabilities that its competitors lack. In recent years, the company has developed such a strong reputation for quality that inspectors sometimes waive tests when they find out that Graniterock delivered the concrete. They know the concrete has already passed more stringent tests at Graniterock than they would put it through. And many of its customers told us that they were willing to pay a premium to buy from Graniterock, because there would be fewer headaches, and the ease of doing business with the company meant that their total costs for many jobs would actually be lower. The company is also a leader in making “green concrete”—that is, concrete that is more environmentally friendly without sacrificing any loss in its engineering performance.

Organizational problem sensitivity requires an infrastructure that makes it easy to capture, analyze, and solve problems. The Clarion-Stockholm puts terminals in behind-the-scenes corridors and staff areas to make it easy for employees to record problems. The application used is the same one that is used to capture ideas, and it categorizes customer problems in a way that makes them easy to analyze. Among other things, this approach allows the hotel to build a stronger case for headquarters in Norway when a bigger problem needs corporate-level involvement or resources. For example, when the hotel first installed Internet in the rooms, the system—which had been negotiated centrally for all hotels by headquarters with the Internet provider—required customers to use cards with access codes that were valid for only eight hours. Guests were supposed to drop by the front desk each day to get their free card and to buy any additional cards if needed. From the outset, customers complained about this system. If a business guest checked e-mail in the morning for ten minutes, the access code would have expired by the time that guest returned at the end of the day.

The receptionists had been telling their supervisors about the guest discontent from the beginning, the supervisors had been telling hotel management, and management had tried to persuade headquarters to negotiate a less cumbersome arrangement with the Internet provider—all to no avail. However, after the idea system was put in place, the staff was able to document the high volume of guest complaints on this topic and demonstrate the extent of the problem. Headquarters relented and renegotiated a better contract.

A similar situation arose with the ventilation system. From the moment the hotel opened, the guests complained incessantly about it. Certain floors had little air circulation and were often stuffy. Unfortunately, it would require a major capital project costing several million dollars to correct the problem, and headquarters was reluctant to authorize the expense. But after being confronted with reports of hundreds of guest complaints about poor ventilation, headquarters got the message and contracted to have the problem corrected.

KEY POINTS

![]() When an idea system is launched, rarely is there a shortage of ideas. Front-line employees are already aware of many problems and opportunities that they have never had a way to correct before. But once the obvious problems have been addressed, the rate at which ideas come in typically slows dramatically. The remedy is ongoing training and education to continually sensitize front-line people to new types of problems.

When an idea system is launched, rarely is there a shortage of ideas. Front-line employees are already aware of many problems and opportunities that they have never had a way to correct before. But once the obvious problems have been addressed, the rate at which ideas come in typically slows dramatically. The remedy is ongoing training and education to continually sensitize front-line people to new types of problems.

![]() Creativity can be divided into problem finding and problem solving. Historically, most organizations have focused on problem solving. But a good idea system significantly multiplies an organization’s problem-solving capacity, so it will burn through the obvious problems faster than they come in. To keep improving, an organization has to get better at problem finding.

Creativity can be divided into problem finding and problem solving. Historically, most organizations have focused on problem solving. But a good idea system significantly multiplies an organization’s problem-solving capacity, so it will burn through the obvious problems faster than they come in. To keep improving, an organization has to get better at problem finding.

![]() Problem finding is often a matter of perspective. An easy way to enhance your employees’ problem-finding abilities is to expose them to fresh perspectives on how the organization might be improved. This will help them to see problems and opportunities that they would not have seen otherwise.

Problem finding is often a matter of perspective. An easy way to enhance your employees’ problem-finding abilities is to expose them to fresh perspectives on how the organization might be improved. This will help them to see problems and opportunities that they would not have seen otherwise.

![]() Idea activators are short training or educational modules that teach people new techniques or give them new perspectives that will trigger more ideas.

Idea activators are short training or educational modules that teach people new techniques or give them new perspectives that will trigger more ideas.

![]() Many ideas have novel perspectives embedded in them. These perspectives are usually implicit, but if drawn out, they have the potential to trigger more ideas. The process of digging out these implicit novel perspectives is called idea mining.

Many ideas have novel perspectives embedded in them. These perspectives are usually implicit, but if drawn out, they have the potential to trigger more ideas. The process of digging out these implicit novel perspectives is called idea mining.

![]() Graniterock’s “short-pay” policy—“if you the customer are not satisfied, … don’t pay us”—is an example of a system to increase an organization’s problem sensitivity.

Graniterock’s “short-pay” policy—“if you the customer are not satisfied, … don’t pay us”—is an example of a system to increase an organization’s problem sensitivity.