CHAPTER 6

How Do We Know It Works?

It was early 2008. By this time, I had heard many stories from people in Mali, Cambodia, El Salvador, and Guatemala about how Saving for Change had changed their lives. From their stories, it was becoming increasingly clear that savings groups made a difference in their ability to save to buy food between planting and the harvest, to be resilient in the face of droughts and unplanned emergencies, and to increase their sense of empowerment.

From the perspective of a government official, international donor organization, or investor, however, it is important not only to hear these stories but to see concrete evidence showing by how much a program has affected a community. Providing answers to this question helps decision makers understand the significance of a program such as Saving for Change, and with good results helps to continue support and funding for such initiatives. Given my career conducting evaluations of other organizations’ international projects, I was eager to examine Saving for Change from this perspective. My staff and I wanted to understand the impact of the groups as thoroughly as possible to make the program stronger. I wanted to learn whether what I believed was happening was borne out by the facts.

To do this, we set up two systems: one for monitoring and another for evaluation. Monitoring allowed us to track group performance on the basis of a set of simple data points, such as number of members, amounts saved and borrowed, loan repayment and outreach, and whether groups continue to save or disband. This would enable the staff to track the spread of the program and how much it cost. Evaluation asked the “so what” questions: Did those who joined groups change how they saved and borrowed? Did their businesses grow? Did their income increase? Did they experience less hunger? Were they more likely to send their children to school? Had their decision-making role in the household and the community changed?

The design of the evaluation started much earlier than 2008. In late 2005, a few months after the first groups in Mali were trained, I designed and launched an initial survey with the help of a Malian research organization. As I visited groups with my local staff to determine what questions to include, I started with this question: What does it mean to be wealthy? One woman’s response remains with me today: “A rich person has enough to eat all year, has cattle and a plow to work the land, and at least a bed to sleep on. A poor person goes hungry, has no cattle, makes do with a hoe, and has nothing at home.”1

Did having Saving for Change groups in a village lead to less hunger and more livestock—the measures of wealth as villagers had defined it so clearly for me before? We were about to find out.

In mid-2008, Oxfam America and Freedom from Hunger secured a major grant from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation to evaluate the impact of participating in Saving for Change groups in Mali and to build the program in Mali, Cambodia, and Guatemala. The grant set aside more than $1.25 million for a large-scale impact evaluation in Mali, where Saving for Change had grown most quickly.2 The Gates Foundation’s decision to investigate the impact of savings groups was made at the same time that several studies were published that were critical of MFIs for overstating the impact of their work.3 The Gates Foundation set aside so much money for research because it wanted there to be no question about the validity of the study. If the results were positive, this would justify further investment in this alternative way to promote rural financial services.

The three-year impact evaluation of Saving for Change in Mali combined a randomized controlled trial (RCT) and an in-depth anthropological study. Economists from Innovations for Poverty Action (IPA) collected baseline data in 2009, interviewing approximately six thousand women in 500 villages where Saving for Change had not yet been introduced. Of these 500 villages, 209 were then randomly selected to receive Saving for Change (“treatment” villages) and 291 were not (“control” villages). Local NGOs then began introducing the program in the selected communities. In 2012 a follow-up survey was conducted to measure the program’s impact after three years, comparing the changes in villages assigned to receive Saving for Change with changes in villages assigned as control sites.

Simultaneously, a team of anthropologists from the Bureau of Applied Research in Anthropology (BARA) at the University of Arizona brought a qualitative lens to the evaluation, conducting fewer but longer and deeper ethnographic case studies in carefully selected representative villages to explain and tease out complex dynamics. The BARA team analyzed nineteen villages, fifteen in the RCT study area and four where Saving for Change had existed since 2006. The anthropologists then tracked changes in these villages over the same three years.

Who Joins Saving for Change Groups?

IPA found that women who joined Saving for Change were generally older and better connected socially in their village, although groups that formed later included women who were more socially marginalized.4 Importantly, while it is true that women who are slightly better off are more likely to join Saving for Change, women in the lowest third household-wealth bracket (as measured by per capita food consumption) still joined in substantial numbers: 42 percent of the top third of households join compared with 33 percent of households in the bottom third.5 Saving for Change is reaching, on average, a third of a village’s poorest women, something that usually takes special targeted programming, a costly outreach effort, and extra training or support, and even then it is rarely achieved.

My strategy since I first designed the program was that the poorest could be reached not by targeting them but by saturating the village with Saving for Change groups. If most women were part of groups, then by definition the poorest would be included. I also knew that the slightly better off would join first because the poorest couldn’t take the risk that their savings might not be safe—they were living too close to the margin of survival.

Did Saving for Change Help to Save for More Food?

To best evaluate the results, it is important to understand the relationship between farming seasons and the availability of food in rural Mali. For poor farmers throughout much of the world, agriculture is driven by rainy seasons when crops are planted and dry seasons that allow mature crops to be harvested, dried, and stored. In between these two natural seasons is the “lean period” of hard work before the harvest, characterized by dwindling or empty stocks of last year’s harvest and similar shortages in the local economy, which drive food prices up to unaffordable levels.6 Unfortunately, in need of cash, many farmers are forced to sell at low prices during the peak harvest season in their area and then buy food back in the lean time–often from the same traders they sold to.7

Prior to the introduction of Saving for Change in the impact-evaluation area, we found that an average of 40 percent of households were food insecure. In addition, we found that after three terrible years marked by drought and political violence, the average percentage of food-insecure households in all villages had risen, but the rise was tempered in the Saving for Change villages—51 percent of households suffered food insecurity in control villages, compared with 47 percent in treatment villages. Likewise, the percentage of households suffering from chronic food insecurity (as opposed to seasonal) was also four percentage points lower (39 percent) in treatment villages than in control villages (43 percent). IPA’s findings also showed that households in treatment villages were better at coping through the hungry season than households in control villages.8

Investing in Livestock

IPA and BARA also found evidence that Saving for Change was helping families save cash for longer periods by enabling them to invest in livestock, or “saving on the hoof.” To save for larger expenditures such as weddings, major illnesses, and funerals, families must find ways to access large sums of money without the risk of keeping that cash on hand, where it might be spent on any number of other daily demands. To this end, investing in animals makes financial sense: they can be a food source, they provide labor for plowing or carting goods, they can literally reproduce and grow, and they make it easier to turn down social demands from a husband, kinsmen, or friends for small cash loans.9 Additionally, because livestock is a traditionally accepted and time-tested method of saving, many Saving for Change members preferred keeping livestock to other forms of banking and credit.10

The results were positive. Households in Saving for Change villages spent, on average per year, more on livestock than households in villages without Saving for Change groups. Also, in treatment areas, livestock was valued at $120 (13 percent) more than in control villages.11

Coping through Hard Times

In the context of a poor, rural household in Mali, the economic benefits of Saving for Change are extremely valuable. Findings from BARA’s research showed that “even marginal benefits to women experienced in [a treatment village] are tremendously appreciated.…. On the one hand, it indicates that for those living on the threshold of vulnerability, even slight improvements are highly meaningful; it is therefore important not to lose sight of the lived experience of Malian women in interpreting the somewhat muted impacts of Saving for Change found in this study. The perception of women in [another treatment village] is instructive in this regard: for them, Saving for Change is seen as the only workable system that is flexible enough to sustain them in times of economic crisis, when most options become untenable, and still allow them to maximize gains in times of relative plenty.”12

Beyond the results of the impact evaluation, people living in villages that received Saving for Change told powerful stories when they were visited by program staff of how the savings groups helped them weather the 2012 food crisis. Mamadou Biteye, who had worked closely with me to design Saving for Change in 2005, reflected on a visit to Mali during the Sahel food crisis in 2012 to assess humanitarian needs there. As part of his assessment he visited some Saving for Change groups and commented that “it was amazing to have a discussion with them because we saw that the ladies were less affected by the food crisis because they could take loans in their groups to purchase food. Because they were members of the groups, they were able to run small businesses, petty trading, or microenterprises that were actually helping them earn money in the market and meet the food needs of their families. It was amazing how these women were much more resilient than those who were not members of groups.”13

Organic Replication of Saving for Change

Voluntary replication was key to meeting our other lofty goal: scaling up. We set expectations for group formation so high that local staff had limited options: try to do everything, which was impossible, or enlist group members to train new groups. If we were to expand Saving for Change to thousands of villages in Mali, we could not do it by hiring a huge staff. Lack of resources spurred creativity. If these women members did not take the lead, then Saving for Change would not meet its objectives. The IPA researchers found that in control villages, almost one-third the number of respondents had joined a group similar to Saving for Change through replication (i.e., without a technical agent forming the group) than in the villages selected to receive Saving for Change training.14 This is a testimony both to the simplicity and the usefulness of this methodology. In determining the costs of introducing Saving for Change into a region, this spontaneous spread of the methodology at no additional cost should be factored in.

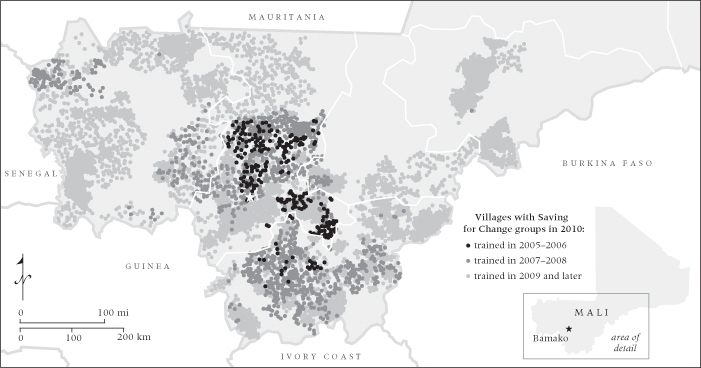

Facing page: Highlighted areas indicate the regions where savings groups were present as of 2010. Source: Oxfam America, 2010

Limits of Impact

Despite these important, measurable accomplishments, some of the hypothesized impacts of the program were not found in the research by IPA and BARA.15 Namely, while consumption smoothing was clearly happening—as was shown in the improvements in food security over the course of a year, the increase in the value of livestock, and the use of loans throughout the year—total income itself did not increase during the time period of the study, although it was better distributed throughout the year.16 Saving for Change increased community-level resilience to cope with seasonal food shortages by helping members respond to shocks. However, Saving for Change in Mali had not catalyzed the long-term community transformations that our team hoped it would, such as increases in school enrollment and money spent on healthcare.17 The timeframe of the impact evaluation may have been too short for these effects to materialize, or difficult years may have prevented these anticipated benefits from emerging. It may also be that Saving for Change does not in fact cause these desired effects.

Women’s Role and Social Capital

With all our focus on participation and member ownership, we wanted to know how much power Saving for Change members really had over their groups’ decisions and resources, as well as their decisions over the loans and savings they brought home. Did Saving for Change empower women in other domains outside the group itself? Did working together in savings groups give women additional respect in their villages or homes and the power to advocate for and shape their lives? Was participation worth their time—as women?

Since the earliest days of Saving for Change in Mali, participants, staff, and several studies have understood that Saving for Change can influence a deeply transformative change in members’ lives. The most inconclusive results from the IPA/BARA study were the findings on decision-making power, social networks, and gender relations.

Findings from BARA’s ethnographic analysis support the hypothesis that social capital increases as a result of participation in Saving for Change. Specifically, they highlighted increases in village-level solidarity and contact with other women and strengthened preexisting social ties. These findings are also consistent with prior research on Saving for Change and formal and informal interviews with countless group members that highlight how Saving for Change helps women build solidarity and confidence. However, results from the RCT do not demonstrate impacts related to social capital. The women did not expand their social networks and were no more likely to take actions, such as speaking to the chief or a government official, than they were before. While the RCT found no increase in the number of the women’s contacts, the BARA anthropologists found that the depth of these relationships had increased.

How Saving for Change Changes Lives: Personal Testimonies

In the patriarchal social and political context of Mali, solidarity should also be understood as an important achievement, even if we hope to one day see Saving for Change allow women to enact more significant, transformational changes in their lives and communities by taking on larger leadership and advocacy roles. Solidarity enables women to better support each other within the choices available to them. Saving for Change, building as it does on indigenous tontine traditions and a participatory design, works from within Malian culture at the direction of Malian women to create accessible support systems adapted to their specific needs and circumstances right now.

Recall the passion with which some replicating agent (RA) volunteers shared their newfound status. Bassa Diakité, an RA, explained to me why she started volunteering and described the confidence and respect that came with that choice:

I did this extra work because of the commitment I have made in front of the other women in the village. If you commit yourself to do something you have to do it. That’s why I try to do everything I can. Even if I’m busy at home I manage to meet the deadline and go to the meeting. … My status changed when I became an RA because of the respect the women now have for me.18

In 2010, Oxfam America’s senior advisor for strategic alliances, Roanne Edwards, traveled to twenty-seven villages around Mali to visit a diverse array of Saving for Change groups that were either unusually successful or unsuccessful (i.e., groups that had dissolved).19 Among the unsuccessful groups, the overwhelming majority failed because the constraints laid out earlier became too onerous. For example, group members did not have the support of their husbands or village leaders (seen as a critical component of success), were unable to afford their weekly contributions because they were already paying off a village pump, or succumbed to interpersonal conflict between younger and older members.20 However, to put this in perspective, these failed groups are among the less than 5 percent that disbanded; the rest are still saving and lending.21

Those groups that succeeded beyond expectations did so in part because they capitalized on Saving for Change’s strengths. According to Edwards, “all place a premium on Saving for Change’s capacity to reinforce group solidarity, elevate members’ respect in their household, and offer a forum for the weekly exchange of ideas.”22 Edwards continued:

In the village of [Fabougou], for example, one Saving for Change group successfully advocated for the building of a maternity clinic with a major donor through a local NGO. Subsequently, the nine village Saving for Change groups organized themselves into teams to pump and transport water to the construction site each day. As the president of one group remarked, belonging to Saving for Change “made it very easy to constitute the work groups because we were used to working together in Saving for Change.” In the village of Banankoro, groups have worked closely with the village chief to gain access to government-run agricultural programs and to invest in a dynamo to provide electricity to the village for a small fee.23

Some of the groups take on projects that will have lasting impacts on gender dynamics for generations to come. For many families in Mali, birth certificates are expensive and therefore usually purchased only for boys. With a birth certificate, girls would also have documentation of their age, reducing the incidence of child marriage and labor and increasing their ability to succeed in school; without one, students may not be allowed to take exams. One Saving for Change village in particular took up the responsibility of acquiring birth certificates for all children of the members of the Saving for Change group, an initiative that required frequent negotiations with their husbands and the village chief.24

Several Saving for Change groups have also taken on the responsibility to train their children to save for things like school fees, generally with small allowances provided by their parents or occasionally by earning income through commercial activities such as making and selling soap. The main benefits of these children’s groups are their role in teaching important financial management skills and providing an extra safety net for the family as one additional savings and loan method in a household’s diverse portfolio. For some households, the savings, which could cover school fees, allowed mothers to make a case for their daughters to go to school.25

Fatoumata Traoré, the former animator who now sits as lead trainer on the technical unit team in Mali, shares another story of women gaining a voice in village-wide decision making through Saving for Change:

One day a development project came to this village to get men and women to identify needs. During the meeting, men refused to invite women. But thanks to the Saving for Change group, all the women were able to be mobilized to choose one woman to go to represent women in this meeting. [Beforehand], everybody discussed their needs as women in this village. After the Saving for Change meeting, they stayed to discuss: we need a garden, we need water. They identified some needs and identified a woman to go to this meeting and discuss with [the development agency]. During this meeting, the chief refused to let the woman into the meetinghouse, but this woman resisted, and eventually the chief accepted and let her tell the project agent the problems of women in the village. The agent said the woman’s suggestions were the best in the meeting. So after this, and for every meeting in the village, the chief wanted that one woman to be there to represent women’s discussions and decisions. Before Saving for Change, the women were not mobilizing together, but thanks to the savings group, they have a communication space.26

Fatoumata believes strongly in the empowering potential of Saving for Change and insists that it is absolutely necessary that poor women take control of their own development. She tells groups she is training:

The financial partners in development in the world are tired of giving money at this time because money is not enough. There are too many problems in the world for them to give you money, so now it is time for you to mobilize your own fund. Even if the development partner wants to help you, they are more attracted to a group that mobilizes its own fund. If someone starts to build a house, it is easy to help them finalize it, but if you have another person who hasn’t started to build, she has nothing to build with, it is very difficult to help this person. It is important to build something with your own resources and capacities. If someone later wants to help you, it will be very easy for them to help you. But you need to start to build something before another can help.27

To Conclude

In Mali, recall that personal wealth is defined as more food and more animals. Villages where Saving for Change was introduced were less likely to be chronically food insecure and their families increased the value of their livestock and savings. The impact evaluation also indicated that substantial numbers of the poorest—those who were in the bottom third in terms of food consumption—had joined groups in substantial numbers, although those who were better off were more likely to join. Reaching the poorest was one of the objectives of the program. Although the evidence for women’s empowerment was inconclusive, and RCT data showed no impact on community engagement or social networks, the anthropologists identified a strengthening of preexisting social ties. Finally, there was strong evidence of the viral, word-of-mouth replication of savings groups in the control villages, further evidence of the relevance and importance of participation in savings groups for members.

In addition to the results from the scientific-impact evaluation conducted by IPA and BARA, the anecdotal observations offered by Mamadou Biteye, Fatoumata Traoré, and Roanne Edwards indicate further change in at least some older groups, and their stories help provide a glimpse of the powerful ways that savings groups in Mali have been able to empower women in rural communities to pursue development on their own terms.