3

THE ROLE OF THE BUSINESS ANALYST

3.1 OVERVIEW

Business analysis has been performed for decades, and despite its long-term existence, the role of the business analyst is still considered fairly new. While the number of business analysts employed is on the increase as the role continues to mature and evolve, the role of the business analyst is often misunderstood and underutilized within organizations. There are several contributing factors to this misunderstanding, including:

- Inconsistent expectations regarding the skills required to perform the role,

- Inconsistent definition of the role and how the skills are applied,

- Lack of understanding about the value the role provides, and

- Failure to recognize that business analysis practices are equally important for program and project success as program and project management practices.

This section explores the business analyst role by examining the position of the business analyst within the organizational structure, discussing the business analyst's sphere of influence in this structure, and discussing important skills that the business analyst may want to develop to be successful. This section intentionally focuses on the role rather than the profession of business analysis to make comparisons between the project manager role, the business analyst role, and other positions within the organization. Although this section uses a specific role title, the information presented here is important to anyone performing business analysis, whether they are performing business analysis with a project manager/business analyst (PM/BA) hybrid title, a business or technical title, or as part of an agile team.

This section is not intended to cover the entire spectrum of information that is currently available to explain the role; rather, it is intended to present an overview and provide a common understanding of the generally accepted key skills required of anyone performing business analysis.

3.2 DEFINITION OF A BUSINESS ANALYST

Those who perform business analysis are commonly called business analysts, but there are business analysis professionals with other job titles who also perform business analysis activities. Some business analysis professionals are specialized and therefore have a title that reflects that area of their competency: strategic business analyst, data analyst, process analyst, or systems analyst are a few examples of these roles. How an organization uses business analysis resources; where these resources functionally report; and the type of industry, type of project, and type of project life cycle being used are some of the factors that influence how organizations title those who have the responsibility for business analysis.

There are also many roles where business analysis is performed as a part of the role but is not necessarily the only responsibility. Enterprise and business architects; portfolio, program, project managers; and operational analysts are a few examples. The business analysis processes, tools, and techniques presented in this guide and standard are relevant to these individuals, too. Because there are many titles and variations of business analysis roles in use, this guide and standard use the phrase business analysis professional over business analyst. When the term business analyst is used, it is done for the sake of brevity and should always be considered a reference to anyone performing business analysis regardless of the title a person holds or the percentage of job function spent on the work. The objective of this guide and standard is to establish an understanding about business analysis and not job titles.

3.2.1 EVOLUTION OF THE ROLE

The evolution of the business analyst role is one of the reasons for the variety of job titles that exists today. Before business analysis was recognized as its own discipline, requirements-related activities were performed by various other roles, such as project managers, software developers, and product quality control analysts (which some organizations refer to as quality assurance analysts).

Developers did not always have the interest or communication and business skills required to work effectively with business stakeholders, and project managers often felt conflicted when they had to forego important needs of the business for the sake of the schedule and cost parameters of the project. Roles such as programmer analyst and systems analyst evolved out of the need and desire to have a dedicated resource focus on the requirements-related work and convert the business requirements into solution requirements for the technical team while ensuring that the procedures and rules that supported those requirements were well understood. While this was an improvement for project teams, these resources tended to come from IT, brought heavy technical experience, and sometimes fell short in meeting the expectations of the business.

Analyst positions on the business side began to appear for the purpose of improving the shortcomings of the technical analyst role. These positions worked well because analysts from the business side understood the day-to-day issues the business faced, understood the context where problems or opportunities existed, and were great advocates for championing the need for change. Frequently, technical expertise was lacking to understand what was possible and feasible and analytical skills were not sufficient when it came to asking probing questions or assessing results from a critical thinking perspective. Today, it is common to find business analysis resources in various areas of the business in addition to IT.

3.2.1.1 CONTINUED EVOLUTION OF THE ROLE

The role of the business analyst has continued to evolve. Trends, such as the rise of the global marketplace, geographically dispersed project teams, advances in technology, and other factors, have continued to influence the evolution of the role. Five developments in business analysis are worth highlighting, as each has been a contributing factor to broadening the role and creating variations in role title:

- Organizations recognizing the value of performing sufficient analysis prior to project initiation to ensure a clear and correct definition of the problem;

- Expansion of business analysis into specialized roles such as the enterprise business analyst who supports strategic planning efforts and portfolio managers building up portfolios with candidate project work;

- Acknowledgment that projects are created to deliver more than software solutions;

- Recognition that for business analysis services to be valuable, they need to be tailored based on project characteristics, including the selected project life cycle; and

- Revelation that many organizations are using a hybrid role for performing project management and business analysis activities.

These subsequent trends resulted in organizations shifting their thoughts on where to place these analytical resources within the organization and how to name and define the role. For example:

- Some organizations moved away from programmer or system analyst titles to recognize the value in also applying analysis practices to non-IT solutions. Examples of roles these organizations use include business process analyst, business rules analyst, business architect, and requirements analyst, among others;

- On the business side, some organizations use roles such as business relationship managers, business development managers, or product owners to represent the needs of the business while using technical analysts to represent IT. These organizations may utilize a business resource to perform pre-project activities such as needs analysis and business case creation and utilize the technical analysts for the requirements-related activities of the project;

- For organizations that have moved to an agile product delivery model, the role of the business analyst is not always discretely recognized. Those organizations will often utilize cross-functional teams, where every team member can usually play more than one role. The team takes on responsibility for business analysis, whether or not there is a team member who holds the role of a business analyst;

- Some organizations, recognizing the value that analytical resources provide, have specialized their analyst positions into roles, such as data analysts, usability analysts, or process improvement analysts, to capitalize on the value provided by those who target and perfect such specialization; and

- For those organizations recognizing that there is some overlap in the skill set utilized by project managers and business analysts, a project manager/business analyst hybrid role may be used.

Although the business analyst role has deep roots within IT, business analysis activities continue to be performed by many roles in non-IT environments. As mentioned in Section 1.1.3, business analysis can be performed when creating or enhancing a product, solving a problem, or seeking to understand customer needs. Many industries and types of projects benefit from business analysis, including construction, health care, and manufacturing. Those who perform business analysis across industries may be called by various other titles that are not included in this guide.

3.2.1.2 WHERE BUSINESS ANALYSTS COME FROM

Because the role of the business analyst has evolved as a result of these trends, it is quite common to find that the person performing business analysis did not start off with a vision to become a business analyst. Many business analysts evolved from other roles, for example, developers, product quality control analysts (referred to quality assurance analysts in some organizations), or subject matter experts from the business. The business analyst is able to bring a wide variety of skills and expertise to the position. Project teams can benefit from this wide variety of skill sets, but variation in skill sets often results in variations in how the role is performed (see Section 3.2.1.3).

Today, no matter whether the role is filled from the business or technical side, the important point is that those who perform business analysis should possess the requisite skills to facilitate collaboration from both the business and IT areas and understand stakeholder needs from all sides.

3.2.1.3 VARIATIONS CAN IMPACT QUALITY

When business analysts lack sufficient skills or the business analysis skills, experience, or competencies they hold vary widely within an organization, business analysis work is not performed consistently across programs and projects. This results in disparate applications of the role, which can lead to teams underperforming or overperforming business analysis. As with any process, reducing variance allows for more consistency in the way activities are performed and allows for repeatability, thereby providing greater effectiveness in execution.

The variation described here should not be confused with tailoring. Tailoring is the need to adjust which business analysis activities are best performed for projects of varying characteristics. For example, tailoring is performed to ensure that business analysis is correctly sized for projects of differing levels of complexity or those having different project life cycles—for example, predictive, adaptive, etc. For more information on tailoring, refer to Section 1.3.4.

The variations referred to in this section are concerned with the inconsistent application of business analysis across projects with similar characteristics. These variations can exist simply because the role is complex and the required skills needed are advanced. Business analysis skills take time to develop. Business analysts who possess different skill sets may gravitate to the business analysis activities in which they are skilled, disregarding activities where they feel ill-equipped. Variations may exist simply because business analysts are unaware of what the organization or project team expects of them or are unaware of the possible value their role can provide. For example, a business analyst who originated from the business side may feel comfortable defining the business need and writing business cases; however, when asked to interact with vendors to assess possible solution approaches, the business analyst may feel inadequate to facilitate the vendor review sessions and incapable of asking probing questions to examine the vendor offerings. In this scenario, business analysis activities are underperformed and a host of undesirable outcomes may result.

3.2.1.4 HOW TO ADDRESS BUSINESS ANALYST VARIANCE

When inconsistent execution of business analysis is a root cause for poor project performance or occurs in an area that places a priority on the consistency of business analysis practices, organizations should explore the inconsistencies to identify why variances in business analysis are present. Possibly, the business analyst position has evolved, creating a moving target to which current business analysts may aspire. Perhaps the discipline lacks a standard process within the organization, or business analysts are being recruited from many areas of the organization but lack formal training. Whatever the reasons are, efforts should be taken to understand the causes.

Organizations may also want to understand the competency level of business analysts both as a whole and at an individual level. In this case, the organization should define the business analyst skills it requires and compare that list to the skills of the existing business analysis resources employed within the organization. A skills analysis such as this is used to identify deficiencies so that measures and plans can address any skill gaps. These gaps can be addressed by augmenting staff with highly trained and certified practitioners such as PMI Professional in Business Analysis (PMI-PBA)® certification holders, by implementing training programs, by establishing a mentorship program, or many other options.

Organizations may also consider self-reflection on past project work to assess where business analysis has worked well and where it hasn't, and then leverage this information to make process and people decisions on future projects. By understanding the types of business analysis skills that a project team is looking for and keeping an accurate inventory of the skills present across business analyst resources, the organization is better able to assign the right mix of business analyst skill sets to future projects.

To minimize variances in the execution of the business analyst role, organizations should consider what structures are lacking. Examples of how organizations add structure into the role of the business analyst include:

- Establishment of a consistent and repeatable business analysis approach that is administered centrally for use across all programs and projects;

- Adoption of industry/best practice standards when the organization does not have a defined process in place;

- Creation of clear job descriptions for business analysts;

- Development of a career path, career framework, and competency ladder to provide guidance on the skills required to advance to the next level within the business analyst job family;

- Establishment of interview checklists and objective methods for evaluating future business analyst new hires; and

- Support of professional development opportunities for business analysts by encouraging involvement in professional associations like PMI, involvement in local PMI chapter events and conferences, or by providing funding for on-demand or classroom training.

3.3 THE BUSINESS ANALYST'S SPHERE OF INFLUENCE

3.3.1 OVERVIEW

Business analysts may lead, but they do not oversee project resources; this is the work of the project manager. A lead business analyst may oversee the work of less experienced business analysts on the team, or a manager of business analysis may be responsible for managing a pool of business analyst resources from an assignment or allocation perspective. At the project level, it is the project manager who is responsible for resource allocation, scheduling, and work progress, including that of business analysts.

Business analysts do manage stakeholder engagement, which is often considered an area of overlap with project managers. Looking more closely, business analysts have different objectives from project managers; therefore, each role manages engagement with stakeholders for different purposes. The business analyst's objective is to ensure that stakeholders remain engaged throughout the entire business analysis process so that the information required to build the solution is attained through ongoing discovery and collaboration and the solution design ultimately meets the needs of the business. The business analyst needs to be aware of stakeholder expectations, availability, and individual interests and the impact each has on the ability to successfully elicit the product requirements. When the dynamics are a cause for one stakeholder group to overpower or shut down another, or when a particular stakeholder becomes disinterested in the solution and begins to withdraw in requirements workshops, it is the business analyst's responsibility to take charge and resolve these situations. Because stakeholder relationships are managed across the project by the project manager, the best tactic is for the business analyst and project manager to work together when stakeholder situations arise regarding the solution. More information about the business analyst's role in managing stakeholder relationships can be found in Section 5.

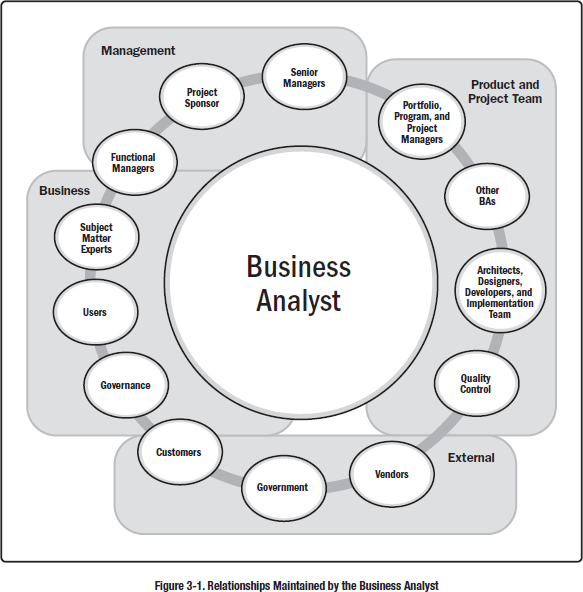

A business analyst works with stakeholders to elicit and analyze business analysis information and evolve and develop the product requirements and other information necessary to achieve a common understanding of the product features across the product team. This makes relationship building and management a very important aspect of the business analyst role. Business analysts maintain a range of relationships that influence the business analysis work. Figure 3-1 highlights some of the stakeholder relationships that business analysts need to manage within their sphere of influence.

3.3.2 THE PRODUCT

The business analyst has accountability for leading stakeholders through a comprehensive process to ensure the successful delivery of the optimal solution. The process begins with a needs assessment and concludes with solution evaluation; all activities are product focused. A product can be tangible or intangible—for example, an organizational structure, a process, or a service.

Almost all of the confusion that occurs on programs and projects between the roles and responsibilities of the project manager and business analyst can be cleared up by understanding that the objectives for each role are different. Project managers are responsible for the successful delivery of the project, while business analysts are responsible for the successful delivery of the product. A product focus requires an understanding of strategy to align proposed solutions and enable the achievement of organizational and business objectives. The product focus is, therefore, much broader than the project focus. The focus on product versus project is a fundamental difference between the roles of the project manager and business analyst. To learn more about the project versus product perspective, refer to Section 1.2.1.

The skills presented in this section and the processes described within Sections 4 through 9 help business analysts successfully deliver solutions to the organizations that hire and employ them.

3.3.3 THE ORGANIZATION

The position of the business analyst within the organization can be very different depending on how the organization leverages the skills of the business analyst. When positioned properly, the business analyst can be a trusted advisor to the business and a liaison to any technical resources. A business analyst can be considered a critical resource on assigned programs and projects and can be considered a leader within the organization. Business analysts require direct access to key stakeholders, so leaders such as the sponsor or project manager can help ensure access by removing any roadblocks that preclude the business analyst from obtaining clear communications with the stakeholders.

As depicted in Figure 3-1, business analysts form a lot of relationships; therefore, relationship building is a critical skill. Business analysts are in an interesting position within the organization, as they have responsibility for leading and influencing stakeholders without possessing the supervisory authority, title, or rank to do so. This can be one of the hardest aspects of the business analyst role, especially when the business analyst lacks the underlying soft skills to make this happen. Business analysts can strengthen their leadership abilities by building trust and demonstrating honesty, integrity, and transparency with those they interact with.

3.3.3.1 BUSINESS ANALYST RELATIONSHIPS

While the major relationships a business analyst develops and manages are vast, the number of relationships that need to be managed increases as the size and complexity of the project or program increases. The following are some of the typical relationships created and managed by business analysts, along with a description of the value that each relationship provides to the organization and the business analyst:

- Business stakeholders and customers. In some organizations and on some programs and projects, the solution developed is delivered internally to business stakeholders. These stakeholders may also be referred to as “the customer” when the solution is addressing a problem or opportunity directly for their business area. Other solutions are developed to service stakeholders who are external to the organization, and typically these stakeholders may be referred to as the customer. Business analysts develop strong relationships with those who will be affected by the development of the solution, whether business stakeholder or customer, as it is their needs that the business analyst is ensuring are addressed in the end product. The category of business stakeholders is a broad one, covering all those with an interest in the business; therefore, it can be made up of other role types, such as subject matter experts or users.

- Design team. Business analysts support the design team by serving as the business advocate and sharing information about the business need and current state environment. The business analyst can review design proposals and provide feedback that the design team values and considers.

- Governance. Depending on the industry, organization, complexity, and risk level of the solution, business analysts often find a need to collaborate with one or more roles within the governance category. Roles considered part of governance include legal, risk, release management, change control boards, DevOps (which some organizations use to coordinate activities and improve collaboration between development and operational areas), a PMO or business analysis center of excellence head, or compliance auditors or officers. Such stakeholders can provide important insights regarding regulations, auditing obligations, business rules, and required organizational processes the product team is obligated to support and adhere to. Business analysts form collaborative relationships with governance roles to ensure that the product development process, including the management of requirements and product information, is performed as required.

- Government. Relationships may need to be established with government agencies at the state, federal, or international level. Typically, product teams are constrained in process or design aspects based on rules and regulations that need to be followed. Business analysts may develop points of contact in these agencies who can provide guidelines, requirements, or answers to questions.

- Functional managers. Building relationships with functional managers can help a business analyst remove roadblocks, obtain subject matter expert resources to participate in elicitation sessions, and gain key insights into business problems or opportunities of significance to the business. Building rapport with managers provides the business analyst with a strong advocate on the business side who can lend support when issues arise over scope or priorities.

- Portfolio and program managers. Business analysts lend analytical expertise to portfolio and program managers to analyze business problems, recommend viable options, and support decision making about which projects to pursue and how best to prioritize projects and project activities. Business analysts perform business case development and feasibility analysis to support portfolio and program management activities.

- Project manager. The business analyst and project manager can greatly influence the success of the project when a strong relationship and partnership is established between the two roles. The project manager/business analyst working relationship should be built upon mutual trust and respect, and all efforts should be made to accentuate each other's strengths. Collaboration is essential to provide a united front to the sponsor, stakeholders, and other project team members. Communication should be aligned, and each role should be able to support the other in most activities.

- Project sponsor. The sponsor champions the product and project, and the business analyst advocates on behalf of the sponsor. The business analyst works closely with the sponsor to define the problem or opportunity and identify solutions to address the business need. The business analyst champions the change throughout the project life cycle, serving as the business advocate—a communication bridge to the project team. The business analyst ensures that the business vision is addressed in the solution.

- Product team. The product team consists of the resources who act together in conducting the work to develop a product. Members of the project team are members of the product team, but not all product team members may be included on the project team. A product team member is anyone a business analyst interacts with when performing the work of business analysis. Some roles, such as enterprise and business architects, lend support across the organization, including supporting business analysis, but may not be directly allocated as a resource on a project team.

- Project team. The project team is a group of individuals who act together in performing the work of the project to achieve its objectives. Regardless of the project life cycle selected, the business analyst should strive for a strong relationship with the project team and should be considered a key member. When an organization or project life cycle does not recognize the role of the business analyst, this does not mean the work of business analysis is overlooked by the project team. A scrum team will have a scrum master, a product owner, and the development team. On projects using an agile approach, business analysts learn that their role responsibilities depend on the needs of the project team and that business analysis responsibilities may be spread across roles. Therefore, the relationship to the project team is always critical, but the business analyst's responsibilities may shift based on the selected project life cycle.

- Product quality control (QC). Developing a good working relationship with the product quality control team, which some organizations refer to as a quality assurance (QA) testing team, provides several benefits. Product quality control analysts are detail oriented and, over time, become experts in the products/solutions they test. This experience is valuable to the business analyst seeking insights into existing solutions. QC analysts are great candidates to review the business analysis deliverables to look for inconsistencies, areas where communications are not clear, or requirements that are not testable. QC analysts should attend requirements review sessions to help business analysts find errors or inconsistencies in requirements and use the experience as an opportunity to ensure a sufficient level of understanding about requirements to conduct the testing activities. QC analysts may even support the business analyst with transition activities. Business analysts can perform a similar review to support QC, looking for errors and issues with test cases and helping QC figure out what to test and by stressing areas of higher risk where testing requires heavier focus.

- Relationship with other business analysts. Business analysts also manage relationships with other business analysts throughout the organization. Business analysis work may be split across multiple roles, where one business analyst takes responsibility for development of the business case and business requirements and others work with stakeholders to define the requirements for a particular stakeholder group. Still other business analysts may be assigned responsibility over developing the solution and transition requirements. Regardless of how work is divided, business analysts build and promote relationships with other business analysts.

When business analysts report into a single functional area, establishing relationships with peer business analysts may be easier than in organizations where business analysts are distributed. Some organizations may establish a business analysis community of practice or a center of excellence to enable collaboration among business analysts. Whether formal structures are in place to enable these relationships or not, business analysts can seek to build a network of business analysts across their organization to learn and share best practices. Senior business analysts and business analyst managers support the profession by increasing the business analysis competency levels and capabilities of business analysis within the organization.

- Subject matter experts (SMEs). Business analysts work with a vast number of SMEs across all business analysis activities, but do so most heavily during elicitation and analysis. The business analyst leverages a variety of soft skills to maintain good working relationships with SMEs. When SMEs lack respect for the business analyst or perceive that there is a lack of credibility, honesty, or transparency with the business analyst, the level of SME engagement declines and the overall quality of the elicitation sessions suffers.

3.3.4 BUSINESS ANALYSIS AND INDUSTRY KNOWLEDGE

Business analysts have an interest in monitoring and staying well informed of changes occurring within the industries where they perform business analysis. Business analysts leverage industry information to understand how trends may impact solutions currently implemented in the organization, processes currently in place, or existing projects, including their associated requirements and proposed solutions.

These trends include but are not limited to:

- Product development,

- New and changing market niches,

- Customer preferences and buying habits,

- Government and international regulations,

- Changes impacting existing or proposed solutions, and

- Business analysis and portfolio and program standards and practices.

3.3.5 PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT

In addition to maintaining relationships with peer business analysts on the job, many business analysts seek to build a network of business analyst relationships outside of work. These external relationships provide the opportunity to obtain and transfer knowledge, find solutions to some of the challenges the business analyst may be facing, obtain insights on emerging trends in the profession, and collaborate with other like-minded professionals.

Because the profession of business analysis is vast, it is difficult for business analysts to get to a point where they feel they have mastered the discipline. Professional development is ongoing in the business analysis profession, and continuing to acquire knowledge is very important. Business analysts also learn by sharing, teaching, coaching, and mentoring other business analysts who are in need of learning. Through technology, there are numerous online communities where business analysts can share templates, white papers, webinars, and other training materials to support one another's professional development needs. Obtaining professional certification can also contribute to one's professional development.

3.3.6 EDUCATING ACROSS DISCIPLINES

In addition to mentoring peer business analysts, there is often a need to educate personnel across the organization on elicitation and modeling techniques or on specific tools the business analyst may be using to collaborate with stakeholders.

Business analysts may need to demonstrate the value of business analysis, increase the acceptance of business analysis within the organization, or advance the efficacy of the business analysis center of excellence. They may serve as internal ambassadors to educate others about the value that business analysis provides to organizational and project success.

3.4 BUSINESS ANALYST COMPETENCIES

3.4.1 OVERVIEW

Proficient business analysts possess a variety of skills that enable them to operate successfully at a senior level. Sections 3.4.2 through 3.4.7 present a summary of the knowledge, skills, and personal qualities a business analyst may consider developing to perform effectively in the role. These competencies are further elaborated in Appendix X3. The skill list provided is not intended to be exhaustive, but instead highlights those skills that are most heavily used. The list of skills can serve as a checklist for business analysts to gauge and measure their personal competencies and to highlight areas where future professional development efforts may be targeted.

3.4.2 ANALYTICAL SKILLS

Analytical skills are utilized by the business analyst to process information of various types and at various levels of detail, break the information down, look at it from different viewpoints, draw conclusions, distinguish the relevant from the irrelevant, and apply information to formulate decisions or solve problems. The analytical skills category is composed of creative thinking, conceptual and detailed thinking, decision making, design thinking, numeracy, problem solving, research skills, resourcefulness, and systems thinking.

3.4.3 EXPERT JUDGMENT

Expert judgment relates to the skills and knowledge obtained from acquiring expertise in an application area, Knowledge Area, discipline, industry, etc., as appropriate for the activity being performed. It includes the skills and knowledge acquired through the collective acquisition of business and project experience. Expert judgment is an important component of a business analyst's decision-making process because previous experiences often have parallels to challenges that a business analyst might be facing. Expert judgment includes the skills to apply acquired knowledge and enterprise environmental factors and organizational process assets to perform work effectively. Expert judgment includes enterprise/organizational knowledge, business acumen, industry knowledge, life cycle knowledge, political and cultural awareness, product knowledge, and standards.

3.4.4 COMMUNICATION SKILLS

Communication skills are utilized to provide, receive, or elicit information from various sources. Due to the number of relationships and interactions that business analysts are required to manage and the amount of information that needs to be exchanged, these skills are some of the most critical ones for the business analyst to master. The communication skills category includes active listening, communication tailoring, facilitation, nonverbal and verbal communication, visual communication skills, professional writing, and relationship building.

3.4.5 PERSONAL SKILLS

Personal skills are skills and quality attributes that identify the personal attributes of an individual. Stakeholders, project team members, and peers use the skills and quality attributes in this category to critique how effective a business analyst is on a personal level. When a business analyst is viewed as being strong in any or all of these skills and attributes, he or she is able to build credibility. The personal skills category is composed of adaptability, ethics, learning, multitasking, objectivity, self-awareness, time management, and work ethic.

3.4.6 LEADERSHIP SKILLS

Leadership involves focusing the efforts of a group of people toward a common goal and enabling them to work as a team. Business analysts leverage these skills to lead disparate groups of stakeholders through various forms of elicitation, to sort through stakeholder differences, to help the business reach decisions on requirements and priorities, and ultimately to gain buy-in to transition a solution into the business environment. The leadership category is comprised of change agent skills, negotiation skills, personal development skills, and skills to enable the business analyst to become a trusted advisor.

3.4.7 TOOL KNOWLEDGE

Tool knowledge is composed of various categories of tools that, if mastered, enable the practitioner to work more effectively. Business analysts use various software and hardware products to help them interact with stakeholders and get work done. The tool knowledge category is comprised of communication and collaboration tools, desktop tools, reporting and analysis tools, requirements management tools, and modeling tools.

For more information regarding the individual knowledge, skills, and personal qualities comprising each skill category in Sections 3.4.2 through 3.4.7, refer to Appendix X3.