5

STAKEHOLDER ENGAGEMENT

Stakeholder Engagement includes the processes to identify and analyze those with an interest in the solution, determining how best to engage, communicate, and collaborate with them; establish a shared understanding of the business analysis activities required to define the solution; and conduct periodic assessment of the business analysis process to ensure its effectiveness. This section presents Stakeholder Engagement from a business analysis perspective.

Within business analysis, the Stakeholder Engagement processes are as follows:

5.1 Identify Stakeholders—The process of identifying the individuals, groups, or organizations that may impact, are impacted, or are perceived to be impacted by the area under assessment.

5.2 Conduct Stakeholder Analysis—The process of researching and analyzing quantitative and qualitative information about the individuals, groups, or organizations that may impact, are impacted, or are perceived to be impacted by the area under assessment.

5.3 Determine Stakeholder Engagement and Communication Approach—The process of developing appropriate methods to effectively engage and communicate with stakeholders throughout the product life cycle, based on an analysis of their needs, interests, and roles within the business analysis process.

5.4 Conduct Business Analysis Planning—The process performed to obtain shared agreement regarding the business analysis activities the team will be performing and the assignment of roles, responsibilities, and skill sets for the tasks required to successfully complete the business analysis work.

5.5 Prepare for Transition to Future State—The process of determining whether the organization is ready for a transition and how the organization will move from the current to the future state to integrate the solution or partial solution into the organization's operations.

5.6 Manage Stakeholder Engagement and Communication—The process of fostering appropriate involvement in business analysis processes, keeping stakeholders appropriately informed about ongoing business analysis efforts, and sharing product information with stakeholders as it evolves.

5.7 Assess Business Analysis Performance—The process of considering the effectiveness of the business analysis practices in use across the organization, typically in the context of considering the ongoing deliverables and results of a portfolio component, program, or project.

Figure 5-1 provides an overview of the Stakeholder Engagement processes. The business analysis processes are presented as discrete processes with defined interfaces, although, in practice, they overlap and interact in ways that cannot be completely detailed in this guide.

KEY CONCEPTS FOR STAKEHOLDER ENGAGEMENT

Stakeholder Engagement involves the activities performed to analyze the needs and characteristics of stakeholders to understand how best to identify, involve, communicate, and work with them in a collaborative manner. Stakeholder Engagement is not unique to business analysis, but when performed within the discipline, the objective is to ensure the best engagement with stakeholders across the business analysis processes.

Much of the work in business analysis involves communication. Stakeholder Engagement processes raise awareness about those who have a connection, either directly or indirectly, to the situation under analysis or the solution. When there is clarity on who needs to be included and involved in the business analysis process and an effort is made to partner and apply practices that are supportive and collaborative, then there are tremendous benefits gained for business analysis and across portfolio, program, and project management. Stakeholder Engagement is about ensuring optimal representation and ongoing interest and involvement from the stakeholder community.

5.1 IDENTIFY STAKEHOLDERS

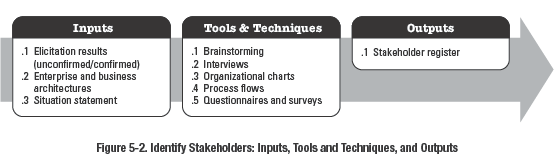

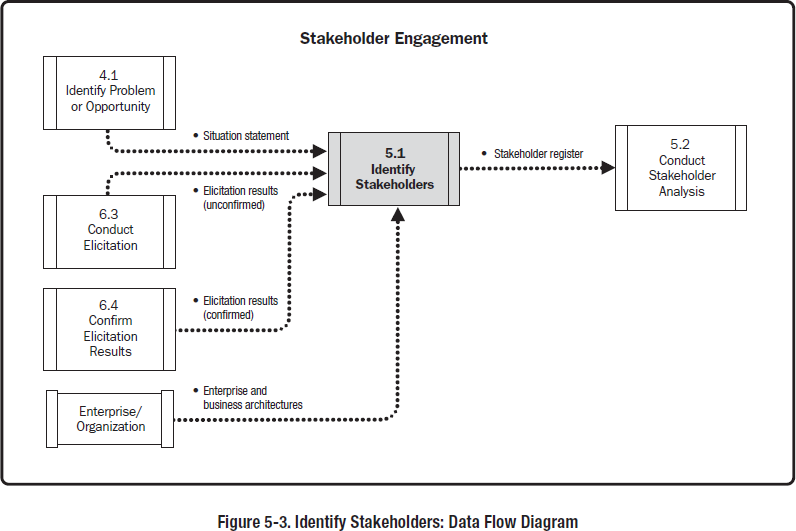

Identify Stakeholders is the process of identifying the individuals, groups, or organizations that may impact, are impacted, or are perceived to be impacted by the area under assessment. The key benefit of this process is that it helps determine whose interests should be taken into account throughout the business analysis–related activities. The inputs, tools and techniques, and outputs of the process are depicted in Figure 5-2. Figure 5-3 depicts the data flow diagram for the process.

According to the PMBOK® Guide, a stakeholder is an individual, group, or organization that may affect, be affected by, or perceive itself to be affected by a decision, activity, or outcome of a portfolio, program, or project. In business analysis, a stakeholder is an individual, group, or organization that may affect, be affected by, or perceive itself to be affected by the solution; therefore, these individuals and organizations can be termed product stakeholders.

Product stakeholders participate in the discovery of requirements and contribute in requirements elicitation by sharing business analysis information from which product requirements are eventually formed. Anyone who initially identifies or perceives him- or herself as a product stakeholder may later have that disposition changed as more information is discovered about the situation and product requirements. Product teams will use the definition of product scope and analysis results produced as the solution evolves to make adjustments to the stakeholder list. Within this standard and guide, the term stakeholder refers to those affected by the solution; hence, product stakeholder is assumed.

Because stakeholder identification is performed as part of business analysis and portfolio, program, and project management, there is the potential for much overlap in effort. Collaboration can ensure that business analysis and portfolio, program, and project management efforts avoid redundancy and gaps and the partnership between roles provides for a better end result.

5.1.1 IDENTIFY STAKEHOLDERS: INPUTS

5.1.1.1 ELICITATION RESULTS (UNCONFIRMED/CONFIRMED)

Described in Sections 6.3.3.1 and 6.4.3.1. Elicitation results consist of the business analysis information obtained from completed elicitation activities. Elicitation occurs across the entire business analysis process. At any point in time, unconfirmed and confirmed elicitation results are available as a source of data for identifying stakeholders. Even results that are unconfirmed can prove valuable when identifying additional areas where potential stakeholders may exist. Sometimes unconfirmed elicitation results will prompt a follow-up discussion with stakeholders, which then leads to further discovery of stakeholders and other product-related information. Through analysis and continued collaboration, the elicitation results used to identify stakeholders can transition from unconfirmed to confirmed, demonstrating the iterative nature of elicitation and analysis within business analysis.

5.1.1.2 ENTERPRISE AND BUSINESS ARCHITECTURES

Described in Section 4.2.1.1. Enterprise and business architectures are a collection of the business and technology components needed to operate an enterprise, including business functions, organizational structures, locations, and processes of an organization. Enterprise and business architectures often contain models and textual descriptions about roles throughout the organization. This information can be utilized as a source for identifying stakeholders. Architecture models can be shared with stakeholders, which may help participants recall missing stakeholders that need to be added to the stakeholder register.

5.1.1.3 SITUATION STATEMENT

Described in Section 4.1.3.2. The situation statement provides an objective statement about the problem or opportunity the business is looking to address, along with the effect and impact the situation is having on the organization. This context is required for determining the scope boundary to guide which stakeholders to include in the stakeholder register.

5.1.2 IDENTIFY STAKEHOLDERS: TOOLS AND TECHNIQUES

5.1.2.1 BRAINSTORMING

Brainstorming is an elicitation technique that can be used to identify a list of ideas in a short period of time (e.g., a list of risks, stakeholders, or potential solution options). Brainstorming is conducted in a group environment and is led by a facilitator. A topic or issue is presented and the group is asked to generate as many ideas as possible about the topic. Ideas are provided freely and rapidly, and all ideas are accepted. Because the discussion occurs in a group setting, participants feed off of one another's inputs to generate additional ideas. The responses are documented in front of the group, so progress is continually fed back to the participants. The facilitator takes on an important role to ensure that all participants are involved in the discussion, and that no individual monopolizes the session or critiques or criticizes the ideas offered by others. Brainstorming is comprised of two parts: idea generation and analysis. The analysis is conducted to turn the initial list of ideas into a usable form of information. Brainstorming can be used during stakeholder identification to build an initial list of stakeholder names. Brainstorming is further discussed in Section 3.3.1.1 of Business Analysis for Practitioners: A Practice Guide.

5.1.2.2 INTERVIEWS

An interview is a formal or informal approach to elicit information from stakeholders. Interviews can be conducted with stakeholders, such as a sponsor or operational managers, to identify the list of stakeholders who will be involved in one or more aspects of the business analysis effort. For more information on interviews, see Section 6.3.2.6.

5.1.2.3 ORGANIZATIONAL CHARTS

Organizational charts are models that depict the reporting structure within an organization or within a part of an organization. These models can be reviewed to facilitate the discovery of stakeholder groups or individuals who may be impacted by or have a potential impact on the solution under analysis.

Existing organizational charts can be used as a starting point or, when these charts are not accessible or nonexistent, new ones can be built from scratch. Organizational charts are best finalized by collaborating with the representatives or individuals being modeled. Based on the size of the organization and how the organizational charts are being used across the business analysis effort, the business analyst determines whether it makes sense to take a role organizational chart down to the individual stakeholder level. If the goal is only to identify the number of groups impacted by the proposed solution, the role organizational chart may be the sufficient level of detail required.

Roles may be conducted differently across the organization and may vary regionally or by the type of customer supported. Stakeholders from the same group may use a product differently. When uncovered during stakeholder analysis, such variations can be reflected in the stakeholder register and can be reflected in a persona that the team creates to further analyze the role. The ultimate goal when reviewing organizational charts is to uncover all the stakeholders who will have needs that will have to be met by the solution and that may have requirements to provide. An oversight of just one role type can result in implementing a solution that fails to meet the needs of hundreds or even thousands of customers. Organizational charts are further discussed in Section 3.3.1.2 of Business Analysis for Practitioners: A Practice Guide.

5.1.2.4 PROCESS FLOWS

Process flows visually document the steps or tasks that people perform in their jobs or when they interact with a product. These models are typically well understood by business stakeholders, so they make for a great tool to facilitate discussions around missing stakeholders or to validate a stakeholder register that has already been started. When identifying stakeholders, the discussion can be focused on understanding the roles responsible for performing existing processes or roles that interact with the outputs produced from these processes. Process flows can be constructed to envision the future state, and any new stakeholders can then be identified by reviewing how work will be performed in the future. For more information on process flows, see Section 7.2.2.12.

5.1.2.5 QUESTIONNAIRES AND SURVEYS

Questionnaires and surveys are written sets of questions designed to quickly accumulate information from a large number of respondents. Surveys can be used to collect information to establish or maintain a stakeholder list. For more information on questionnaires and surveys, see Section 6.3.2.9.

5.1.3 IDENTIFY STAKEHOLDERS: OUTPUTS

5.1.3.1 STAKEHOLDER REGISTER

In project management, a stakeholder register is a project document that includes the identification, assessment, and classification of project stakeholders. In business analysis, any individual, group, or organization that may affect, be affected by, or be perceived to be affected by the proposed or intended solution is added to the stakeholder register.

5.1.4 IDENTIFY STAKEHOLDERS: TAILORING CONSIDERATIONS

Adaptive and predictive tailoring considerations for Identify Stakeholders are described in Table 5-1.

Table 5-1. Adaptive and Predictive Tailoring for Identify Stakeholders

| Aspects to Be Tailored | Typical Adaptive Considerations | Typical Predictive Considerations |

| Name | Identify Stakeholders | |

| Approach | Stakeholders are identified during initial planning, often using brainstorming, and can be revisited at any point throughout the adaptive life cycle as stakeholders are discovered. | List of stakeholders is identified during business analysis planning and can be revisited/revised if the product scope changes or elicitation and analysis activities identify new stakeholders. |

| Deliverables | Might be a list of stakeholders noted in lightweight documentation or models may just involve brainstorm results. | Stakeholder register; may require the use of an approved stakeholder register template. |

5.1.5 IDENTIFY STAKEHOLDERS: COLLABORATION POINT

Enterprise and business architects model aspects of the organization, including information pertaining to internal human resources and supporting external people resources that have relationships to the enterprise. Architects may be able to share models depicting current organizational units, roles, and skills to augment stakeholder identification activities.

5.2 CONDUCT STAKEHOLDER ANALYSIS

Conduct Stakeholder Analysis is the process of researching and analyzing quantitative and qualitative information about the individuals, groups, or organizations that may impact, are impacted, or are perceived to be impacted by the area under assessment. The key benefit of this process is that it provides important insights about stakeholders that can be used when choosing elicitation and analysis techniques, selecting which stakeholders are appropriate to involve at different times in the business analysis efforts, and determining the best communication and collaboration methods to use. The inputs, tools and techniques, and outputs of the process are depicted in Figure 5-4. Figure 5-5 depicts the data flow diagram for the process.

Stakeholder analysis is performed to systematically review and consider quantitative and qualitative information to understand stakeholder characteristics and to determine the interests and positions that the stakeholders have in the solution. Such analysis is often conducted during planning so the product team can understand the stakeholder impacts and influences on the business analysis process as early as possible. The results of stakeholder analysis are used to develop effective approaches to interact and communicate with stakeholders throughout the project and specifically the requirements-related activities.

Stakeholder analysis is performed iteratively and is revisited throughout the project as new stakeholders are discovered or existing stakeholder relationships or characteristics change. Refinements to the product scope may result in the addition or removal of stakeholders. Early planning will produce the initial stakeholder list, but further stakeholder identification will maintain it. When a large number of stakeholders is identified, stakeholder analysis may involve grouping the stakeholder list by common characteristics, which helps streamline analysis.

Any number of characteristics may be analyzed during stakeholder analysis to develop clearer insights about the stakeholders identified in Section 5.1. The information gleaned from this analysis helps with decision making, when establishing roles and responsibilities, and in determining how best to engage and collaborate with stakeholders. The analysis can also be used to determine which stakeholders should be engaged based on the situation. Some characteristics might include the following:

- Attitude. Identifies who is and who is not supportive, interested, or motivated to support the work and accept the recommended solution option.

- Experience. Provides understanding about the industry, organization, and solution experience the stakeholder may provide the team during the business analysis effort.

- Interests. Identifies stakeholders who obtain positive or negative gains from the solution. This, in turn, may impose positive and negative impacts to the requirements-related activities.

- Level of influence. Detects those who have influence within the organization or product team that may hinder or support the proposed solution.

Any number of characteristics can be chosen for analyzing stakeholders. The product team works together to determine which characteristics to consider. Stakeholder analysis and characteristics are further discussed in Section 3.3 of Business Analysis for Practitioners: A Practice Guide.

5.2.1 CONDUCT STAKEHOLDER ANALYSIS: INPUTS

5.2.1.1 ELICITATION RESULTS (UNCONFIRMED/CONFIRMED)

Described in Sections 6.3.3.1 and 6.4.3.1. Elicitation results consist of the business analysis information obtained from completed elicitation activities. Past results of prior discussions and elicitation activities may be used when analyzing characteristics about stakeholders. Even when elicitation results are unconfirmed, the information can serve as a starting point for performing this work. Through analysis and continued collaboration, the elicitation results used to perform stakeholder analysis may transition from unconfirmed to confirmed, demonstrating the iterative nature of elicitation and analysis within business analysis.

5.2.1.2 ENTERPRISE AND BUSINESS ARCHITECTURES

Described in Section 4.2.1.1. Enterprise and business architectures are a collection of the business and technology components needed to operate an enterprise, including business functions, organizational structures, locations, and the processes of an organization. Enterprise and business architectures contain models and textual descriptions about the various roles within the organization. Such information can be utilized as a starting point when beginning to analyze stakeholders.

5.2.1.3 SITUATION STATEMENT

Described in Section 4.1.3.2. The situation statement provides objective information to understand the problem or opportunity that the business is looking to address, along with the organizational impact. This context is required during stakeholder analysis to make the determinations and categorizations about stakeholders and how each is impacted by the recommended solution option.

5.2.1.4 STAKEHOLDER REGISTER

Described in Section 5.1.3.1. A stakeholder register is a product document that includes the identification, assessment, and classification of project stakeholders. In business analysis, any individual, group, or organization that may affect, be affected by, or be perceived to be affected by the proposed or intended solution is added to the stakeholder register. The stakeholder register provides the most current list of stakeholders for performing a stakeholder analysis. The register is maintained during business analysis and portfolio, program, and project management activities.

5.2.2 CONDUCT STAKEHOLDER ANALYSIS: TOOLS AND TECHNIQUES

5.2.2.1 JOB ANALYSIS

Job analysis is a technique that can be used to identify the job requirements and competencies required to perform effectively in a specific job or role. It can be used to determine training needs, as a precursor to writing a job posting, or to support a performance appraisal process. The technique is often used when a new job is created or when an existing job is modified to draft the job description and assist in identifying a recommended list of qualifications for the position.

The output of job analysis may include details such as a high-level description of the work, a depiction of the work environment, a detailed list of the activities a person is expected to perform, a listing of the preferred interpersonal skills, or a list of required training, degrees, and certifications.

The results of job analysis can be used during business analysis to gain insights into stakeholder roles, which is especially helpful when the project entails replacing or revising workflow and business processes. When the solution will involve the creation of one or more new roles, this technique may be used to specify the tasks required for the new positions and the qualities and characteristics needed to be successful in the job. Job analysis is further discussed in Section 3.3.3.1 of Business Analysis for Practitioners: A Practice Guide.

5.2.2.2 PERSONA ANALYSIS

A persona is a fictional character created to represent an individual or group of stakeholders, termed a user class. For an individual class, a persona can include any number of descriptive features the team decides are worth capturing—for example, a name, narrative, goals, behaviors, motivations, hobbies, environment, demographics, and/or skills. The persona narrative, if included, tells a story about the user class. The objective is to analyze usage information or draw out stakeholder requirements to determine how a user class interacts with a solution. A persona can range in size from a summary paragraph to a one- to two-page description, depending on the characteristics the team agrees to capture. Unlike a stakeholder, a persona may or may not have an interest in the outcome of the project and can be a user with no influence over the solution.

Persona analysis is a technique that can be used to analyze a class of users or process workers, to understand their needs or product design and behavior requirements. During stakeholder analysis, the results of persona analysis can provide insights that can be used to structure a more effective business analysis approach. Personas can be used in product development or IT systems development to design or map out user experiences. Although it may not be possible to obtain requirements for every stakeholder on the stakeholder register, stakeholders can be grouped into user classes and a persona built to understand the needs of each by the class that represents them.

The main difference between a persona and a stakeholder is that the persona is a fictional representation and a stakeholder is an actual person. The main difference in describing personas and stakeholders is that personas include more detail about how the person or group operates within the problem or solution space. For example, personas might describe device literacy, preferred methods for performing tasks, and frequency of performing specific actions. Generally, this kind of in-depth information is not needed for all stakeholders, and is therefore applied to only the most critical or most impacted stakeholders. Persona analysis is further discussed in Section 3.3.3.2 of Business Analysis for Practitioners: A Practice Guide.

5.2.2.3 RACI MODEL

A RACI model is a common type of responsibility assignment matrix that uses Responsible, Accountable, Consult, and Inform designations to define the involvement of stakeholders in activities. Portfolio, program, or project managers may develop a RACI model to identify roles and responsibilities for a body of work. In business analysis, a RACI can be developed to communicate the roles and responsibilities of those involved in the business analysis effort. Product teams should avoid assuming that everyone involved in the business analysis process will understand their roles and work assignments. Stakeholders can be confused when they participate on more than one project team and fulfill differing roles. Stakeholders may also have confusion about the roles they are assigned versus the roles they desire. Determining roles and responsibilities with a RACI model helps minimize confusion and conflicts, especially in areas where responsibilities appear to overlap.

Stakeholder analysis involves describing how stakeholders may be categorized by classifications, such as their power, influence, impact, or interest. Such classifications can help determine the level of involvement stakeholders may have, as well as the roles they hold within the business analysis process. Engagement-level classifications, such as unaware, resistant, neutral, supportive, and leading, can be used to consider the current and desired level of engagement of any stakeholder or stakeholder group with the product or project, which will be taken into consideration as part of formulating the stakeholder engagement approach during planning.

These classifications, in turn, may be used to determine what signifies an appropriate level of involvement and how to classify stakeholders within the RACI model. The RACI model demonstrates that stakeholders can have different levels of involvement at different points within a product or project life cycle or within different business analysis processes. The RACI model will highlight single points of accountability and those situations where there is joint accountability. The RACI classifications are as follows:

- R—Role or person “responsible” for performing the task.

- A—Role or person “accountable” for the completion/quality of the task; final approver.

- C—Role or person who may be “consulted” to obtain information to complete the task.

- I—Role or person who is in some manner impacted by the task, and hence, needs to be “informed” or kept up to date on the progress and work being performed to complete the task.

Table 5-2 shows a sample format of a RACI model. RACI models are further discussed and an example is provided in Section 2.3.1 of Business Analysis for Practitioners: A Practice Guide.

5.2.2.4 STAKEHOLDER MAPS

Stakeholder maps are a collection of techniques used for analyzing how stakeholders relate to one another and to the solution under analysis. Several stakeholder mapping techniques exist. The stakeholder matrix and onion diagram are just two of these and are explained below:

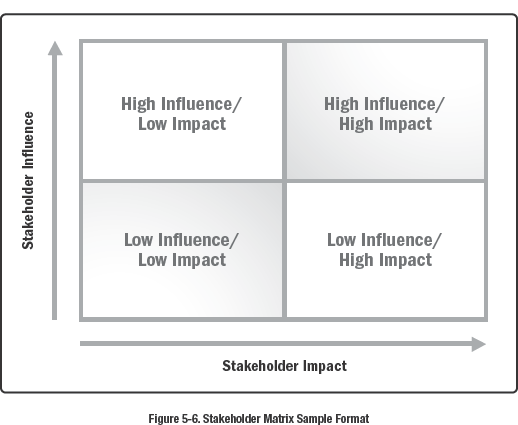

- Stakeholder matrix. A stakeholder matrix is a technique that uses a quadrant or matrix to analyze a set of stakeholders. The x and y axes are labeled with the names of the variables the product team chooses to analyze by, for example:

- Influence. How much the stakeholder may influence product requirements, and

- Impact. How significantly the solution will impact the stakeholder once it is implemented.

Each stakeholder name or group name is placed in one of the four quadrants, as depicted in Figure 5-6. A matrix analyzing impact to influence would result in the following relationships:

- High influence/low impact. Stakeholders categorized in this group may serve as product champions or advocates for the solution team and business analysis effort. This category includes decision makers who are not directly impacted by the solution but may manage one or more stakeholder groups that are. Although this group of stakeholders may defer the functional requirements work to subject matter experts (SMEs) reporting to them, it is still prudent to maintain open communications with stakeholders in this category to leverage their support and advocacy.

- High influence/high impact. This quadrant signifies a critical group of stakeholders to engage with during the business analysis process and requirements-related activities. These stakeholders are critical sources for requirements; therefore, planning should allocate a significant amount of the total business analysis effort to these stakeholders. Stakeholders here require frequent communication and are important resources with whom to build a strong partnership and trusting relationship because they have the influence to make or break an initiative.

- Low influence/low impact. These stakeholders should not be ignored, and should be included in initial discussion to validate that their relationship is assessed correctly. These stakeholders may find that their requirements are some of the last to be factored into the final product or may have the value of such requirements ranked so low that the requirements are never implemented by the solution team. Stakeholders here may have no impact and may have no interest or awareness of the effort. The stakeholders in this category should be monitored to ensure that their relationship to the solution does not change as the solution definition evolves.

- Low influence/high impact. Stakeholders categorized in this group are also critical sources for requirements. Although the stakeholders themselves may not hold significant power within the organization, they could be represented by an individual who does. Stakeholders here may represent a significant portion of the product requirements; therefore, this is an area where adequate time should be spent understanding the situation and later eliciting requirements. Attention should be given to ensure that communication is reaching this stakeholder group and that any concerns they have are known and addressed. Stakeholders in this group may represent those expected to adapt to the implemented solution once it is built.

Figure 5-6 shows a sample format of a stakeholder matrix.

- Onion diagram. An onion diagram is a technique that can be used to model relationships between different aspects of a subject. In business analysis, an onion diagram can be created to depict the relationships that exist between stakeholders and the solution. The solution may represent one or more products. The stakeholders can be internal or external to the organization. Once built, this model can help the team analyze stakeholders by representing the strength or significance of the relationships of the people to the solution. Stakeholders modeled closest to the center of the onion represent those who have the closest or strongest relationship to the solution—for example, end users or product development stakeholders. Stakeholders modeled on the outer portion of the onion represent those with a less significant relationship. The team can decide the meaning of the layers or relationships being modeled. One example is as follows:

- Layer 1. Those directly involved with the development of the solution.

- Layer 2. Stakeholders whose activities are directly enhanced or modified by the implemented solution.

- Layer 3. Stakeholders who work or interact with those who are directly impacted by the implemented solution.

- Layer 4. External stakeholders.

Figure 5-7 shows a sample format of an onion diagram.

The onion diagram is a good choice when the team is looking for a concise way to communicate information about stakeholder relationships. Other methods, such as brainstorming or analyzing organizational charts, work well as companion techniques to help teams identify the stakeholder roles that need to be depicted in the onion diagram. For more information on organizational charts, see Section 5.1.2.3. For more information on brainstorming, see Section 5.1.2.1.

5.2.3 CONDUCT STAKEHOLDER ANALYSIS: OUTPUTS

5.2.3.1 UPDATED STAKEHOLDER REGISTER

The results of stakeholder analysis may include the addition or modification of stakeholder names or the addition or modification of any of the supporting information pertaining to stakeholder characteristics. Maintaining an accurate stakeholder register is critical to successful business analysis because the oversight of any one stakeholder could result in the loss of critical product requirements. Table 5-3 shows a sample format of a stakeholder register.

5.2.4 CONDUCT STAKEHOLDER ANALYSIS: TAILORING CONSIDERATIONS

Adaptive and predictive tailoring considerations for Conduct Stakeholder Analysis are described in Table 5-4.

Table 5-4. Adaptive and Predictive Tailoring for Conduct Stakeholder Analysis

| Aspects to Be Tailored | Typical Adaptive Considerations | Typical Predictive Considerations |

| Name | Stakeholder or Persona Analysis | Stakeholder Analysis |

| Approach | Stakeholder interests and influences as related to expected solution value; performed during initial planning or early iterations and can be revisited prior to the start of an iteration when specific details regarding stakeholders are required for the next iteration. | Any number of stakeholder characteristics analyzed; performed during business analysis planning and can be revisited/revised if the product scope changes, as elicitation and analysis activities identify new stakeholders needing to be analyzed, or across the project life cycle as stakeholder attitude and influence levels may change. |

| Deliverables | May include stakeholder maps, personas, models, or lightweight documentation. | Stakeholder register that includes a listing of stakeholder names and characteristics. |

5.2.5 CONDUCT STAKEHOLDER ANALYSIS: COLLABORATION POINT

Project managers and business analysts encounter an overlap with regard to stakeholder analysis activities because both roles have a vested interest in understanding stakeholder characteristics and managing stakeholders. On adaptive life cycle projects, the overlap or interest and responsibility may exist between any roles performing this analysis. To ensure that redundancy of effort is avoided, business analysts and portfolio, program, and project managers should complete this work collaboratively. Each role provides a unique perspective, with portfolio, program, and project managers analyzing stakeholders for impacts to the portfolio, program, and project, respectively, and business analysts analyzing stakeholders for impacts to the solution and to ensure an effective business analysis process. For the sake of the stakeholders, the product team needs to operate as a cohesive unit and avoid making uncoordinated and redundant requests of stakeholders.

5.3 DETERMINE STAKEHOLDER ENGAGEMENT AND COMMUNICATION APPROACH

Determine Stakeholder Engagement and Communication Approach is the process of developing appropriate methods to effectively engage and communicate with stakeholders throughout the product life cycle, based on an analysis of their needs, interests, and roles within the business analysis process. The key benefit of this process is that it provides a clear, actionable approach to engage stakeholders throughout business analysis and requirements-related activities, so that stakeholders receive the right information, through the best communication methods and frequency to satisfy the needs of the initiative and meet stakeholder expectations.

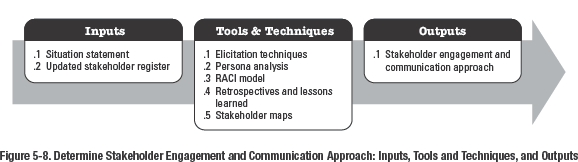

The inputs, tools and techniques, and outputs of the process are depicted in Figure 5-8. Figure 5-9 depicts the data flow diagram for the process.

Determining stakeholder engagement and communication means devising different ways to secure an optimal level of commitment from stakeholders at appropriate points in the product life cycle. The stakeholder engagement and communication approach is developed by taking into consideration the results of stakeholder analysis, relevant organizational norms and standards, and lessons learned from past engagements with stakeholders.

A stakeholder engagement and communication approach often has five components:

- The level of involvement of each stakeholder or stakeholder group, often based on the RACI and other characterizations of stakeholders as summarized in the stakeholder register;

- The approaches for making decisions, such as decision by consensus, decision by sponsor, or decision by weighted analysis. These decision-making approaches are typically defined collaboratively with stakeholder input, taking organizational norms and standards into account;

- The approach for obtaining approvals, including who can approve requirements and other product information and who can reject requirements. The approach for approvals also includes the necessary level of approval formality, such as whether sign-off is required, and if it is, whether an electronic signature or email approval is acceptable;

- How product and project information will be structured, stored, and maintained in support of keeping stakeholders and others informed. Organizational standards for standard knowledge repositories, requirements management tools, modeling tools, agile team tools, and record retention policies often drive the options that are available. Within these options, wherever possible, stakeholder preferences are considered; and

- How stakeholders will be kept up to date about product and project efforts, taking into account which stakeholders need which information, as well as stakeholder preferences for the level of detail of communication, frequency of communication, and the time zones where the stakeholders are located. Additionally, organizational options for communication media and tools will be considered, such as specific communication technology available, authorized communication media, videoconferencing, remote collaboration tools, and security requirements. Within these options, wherever possible, stakeholder preferences are considered.

When dealing with stakeholders who are external to the organization, the same factors have to be considered, such as the best method and timing for delivering communications. Communication to external stakeholders may be initiated from and channeled through single points of contact at both the initiating and receiving ends to ensure consistency in messaging.

For business analysis, there is rarely a one-size-fits-all way to communicate requirements and other product information to all stakeholders. Yet, when tailoring considerations make communication very complex, communication to stakeholders may become very time-consuming. The following questions help to determine what and how to communicate and who might do the communicating:

- Who actually uses this kind of information?

- Does this information need to be in a formal document?

- Does this information need to be written at all, or can it be conveyed in some other way?

Communication approaches are further discussed in Sections 3.4.11 of Business Analysis for Practitioners: A Practice Guide.

There is significant overlap between the business analysis perspective of stakeholder engagement and communication and how portfolio, program, and project managers view it. Although overlaps exist, the focus is somewhat different between roles. For example, business analysts are responsible for stakeholder engagement during product development, while portfolio, program, and project managers are responsible for stakeholder engagement within their purview. It is imperative for business analysts to work with portfolio, program, and project managers to determine which stakeholders need to be involved in the product life cycle and their appropriate level of involvement, and to avoid redundancies and inconsistencies in communications. Additionally, business analysts often rely on portfolio, program, and project managers, or work with them, to negotiate and secure the desired commitment from the stakeholders.

Taking time to consider how best to engage and communicate with stakeholders is accomplished in many ways, ranging from the highly formal to the very informal. In organizations with a need or desire for formality, the stakeholder engagement and communication approach becomes a component of a formal business analysis plan, which is discussed in more detail in Section 5.4. Efforts using an adaptive life cycle also require communication/collaboration to be successful; “planning communication” is inherent in the life cycle itself and is not an activity that is formally performed.

No matter how formally or informally one plans out engagement and communication, the thought process is critical for successful product development. In its absence, stakeholders may end up being involved on an ad-hoc basis or whenever they have time to spare. In such situations, a product team risks not obtaining sufficient stakeholder involvement for elicitation, analysis, and decision making; not having a good balance of stakeholder interests represented; and not considering stakeholder preferences for communication, all of which can adversely impact solution decisions and development.

5.3.1 DETERMINE STAKEHOLDER ENGAGEMENT AND COMMUNICATION APPROACH: INPUTS

5.3.1.1 SITUATION STATEMENT

Described in Section 4.1.3.2. The situation statement is an objective statement of a problem or opportunity. The statement, along with a list of stakeholders identified in the stakeholder register, provides context to understand the analysis area and guide decisions about the engagement and communication approach.

5.3.1.2 UPDATED STAKEHOLDER REGISTER

Described in Section 5.2.3.1. The updated stakeholder register contains the results of stakeholder analysis, including the addition or modification of stakeholder names and any supporting information pertaining to stakeholder characteristics. The characterization of the stakeholders obtained through stakeholder analysis is a key factor for determining how a stakeholder will best participate in product development activities.

5.3.2 DETERMINE STAKEHOLDER ENGAGEMENT AND COMMUNICATION APPROACH: TOOLS AND TECHNIQUES

5.3.2.1 ELICITATION TECHNIQUES

Elicitation techniques are used to draw information from sources. As part of determining the stakeholder engagement and communication approach, it's important to work directly with the stakeholders to understand their mindset, what they need, and what will work best for them to engage. Doing so also helps develop or enhance good relationships with them. A few common elicitation techniques that can support determining the stakeholder engagement and communication approach are brainstorming, facilitated workshops, and interviews:

- Brainstorming. A technique used to identify a list of ideas in a short period of time. It can be used to generate ideas for communication approaches and how to keep all stakeholders engaged. For more information on brainstorming, see Section 5.1.2.1.

- Facilitated workshops. Structured meetings led by a skilled, neutral facilitator and a carefully selected group of stakeholders to collaborate and work toward a stated objective. The structure of a facilitated workshop promotes an efficient and focused meeting for the stakeholders to discuss engagement and communication. For more information on facilitated workshops, see Section 6.3.2.4.

- Interviews. A technique used to elicit information for the stakeholder engagement and communication approach. They can be scheduled with various stakeholders who possess key information at times that are convenient for them. When necessary, individual interviews can provide each stakeholder with an opportunity to speak candidly about concerns regarding stakeholder engagement. For more information on interviews, see Section 6.3.2.6.

For more information on elicitation techniques, see Section 6.3.2.

5.3.2.2 PERSONA ANALYSIS

A persona is a fictional character created to represent an individual or group of stakeholders. When stakeholder types have been characterized by personas, continuing analysis to look for patterns may suggest effective ways to engage and communicate with them. For more information on persona analysis, see Section 5.2.2.2.

5.3.2.3 RACI MODEL

The RACI model is a common type of responsibility assignment matrix that uses responsible, accountable, consult, and inform designations to define the involvement of stakeholders in activities. A RACI model can be used to present the desired level of involvement of each stakeholder or stakeholder group for different business analysis activities. The results of RACI modeling can be used to understand assigned responsibilities and how best to engage and communicate with the stakeholders and groups identified. For more information on RACI models, see Section 5.2.2.3.

5.3.2.4 RETROSPECTIVES AND LESSONS LEARNED

Retrospectives and lessons learned use past experience to plan for future work. An optimal stakeholder engagement and communication approach may consider recommendations provided from past projects or prior iterations, or may apply past lessons about approaches that worked well for similar product development efforts. For more information on retrospectives and lessons learned, see Section 5.7.2.4.

5.3.2.5 STAKEHOLDER MAPS

Stakeholder maps help with the analysis of stakeholder characteristics such as the power, influence, impact, and interest of stakeholder groups. Ongoing stakeholder mapping and consideration of the current and desired level of engagement by stakeholders is part of determining the stakeholder engagement and communication approach. For more information on stakeholder maps, see Section 5.2.2.4.

5.3.3 DETERMINE STAKEHOLDER ENGAGEMENT AND COMMUNICATION APPROACH: OUTPUTS

5.3.3.1 STAKEHOLDER ENGAGEMENT AND COMMUNICATION APPROACH

The stakeholder engagement and communication approach summarizes agreements for the level of involvement of each stakeholder or stakeholder group; the approaches for making decisions and obtaining approvals; how product and project information are structured, stored, and maintained in support of keeping stakeholders and others informed; and how stakeholders are kept up to date about product and project information and efforts.

5.3.4 DETERMINE STAKEHOLDER ENGAGEMENT AND COMMUNICATION APPROACH: TAILORING CONSIDERATIONS

Adaptive and predictive tailoring considerations for Determine Stakeholder Engagement and Communication Approach are described in Table 5-5.

Table 5-5. Adaptive and Predictive Tailoring for Determine Stakeholder Engagement and Communication Approach

| Aspects to Be Tailored | Typical Adaptive Considerations | Typical Predictive Considerations |

| Name | Not a formally named process | Determine Stakeholder Engagement and Communication Approach |

| Approach | The product owner, representing stakeholder needs and preferences for communication, and the rest of the team verbally agree on the format and level of detail of product information to be communicated. Stakeholder engagement and communication is taken into account as part of overall preliminary and ongoing collaborative team planning. When team members are colocated, most communication can occur in person. | Planning ideas about whom to engage, what information to communicate, and how to engage and communicate with stakeholders are incorporated into the business analysis plan. Planning activities occur prior to the start of elicitation. May specify the format and level of detail of product information to be communicated and how that will vary by stakeholder or stakeholder group. |

| Deliverables | Not a separate deliverable. | Stakeholder engagement and communication approach becomes a component of the business analysis plan. |

5.3.5 DETERMINE STAKEHOLDER ENGAGEMENT AND COMMUNICATION APPROACH: COLLABORATION POINT

Senior managers have the broadest understanding of whether stakeholder priorities are complementary or conflicting. Product teams can work together to vet the stakeholder engagement and communication approach with senior managers, especially when organizational priorities or politics have an impact on stakeholder participation. Collaboration with portfolio, program, and project managers is essential to ensure that stakeholder engagement and communication approaches are aligned.

5.4 CONDUCT BUSINESS ANALYSIS PLANNING

Conduct Business Analysis Planning is the process performed to obtain shared agreement regarding the business analysis activities the team will be performing and the assignment of roles, responsibilities, and skill sets for the tasks required to successfully complete the business analysis work. The results of this process are assembled into a business analysis plan that may be formally documented and approved or may be less formal depending on how the team operates. Whether the plan is formally documented or not, the results from all of the planning processes should be considered in the overall approach. Failing to make planning decisions can result in a less than optimal approach when performing the business analysis work. The key benefit of this process is that it sets expectations by encouraging discussion and agreement on how the business analysis work will be undertaken and avoids confusion regarding roles and responsibilities during execution.

The inputs, tools and techniques, and outputs of the process are depicted in Figure 5-10. Figure 5-11 depicts the data flow diagram for the process.

The process of conducting business analysis planning has three main objectives:

- Aggregates all of the Knowledge Area approaches into a cohesive set of agreements and decisions about how business analysis will be conducted,

- Produces an estimation of the level of effort for business analysis activities, and

- Assembles a business analysis plan from the component approaches and the estimates.

The activities associated with each of these components are accomplished in markedly different ways for efforts that use a plan-driven, predictive life cycle as opposed to those using a change-driven, adaptive life cycle. These differences are explained in this section and in Section 5.4.4.

When developing the business analysis plan, it is a good practice to provide explanations for the planning choices made. For example, for projects using an adaptive life cycle, the depth and cadence of analysis activities will be planned differently from projects that use a predictive life cycle. Explaining why planning choices were selected provides context for those who review the plan and provides a rationale for the decisions made.

Solutions developed using a predictive life cycle typically use a plan-driven approach for estimation and planning. Estimates are usually created for each role involved in an effort, either from the beginning to the end of the effort or broken out by phases. The level of detail of the estimates may vary, depending on the planning techniques chosen. From a business analysis perspective, this means that separate time estimates are created for the expected effort needed to complete each discrete business analysis task. Once the tasks are estimated, they are structured into an appropriate work plan.

Teams that develop solutions using a change-driven, adaptive life cycle still need to think about business analysis tasks, the level of effort and duration of tasks, dependencies and constraints, and the sequence of activities. However, with the possible exception of tasks to refine large or complex product backlog items that the team may soon develop, business analysis effort and business analysis tasks are not typically broken out as separate line items for estimating and planning purposes.

For an adaptive life cycle approach, as part of a planning session that deliberately occurs at the release level, prioritization is typically used as a primary planning factor. For planning that deliberately occurs at the beginning of each iteration, prioritization and just-in-time estimating are used to select the product backlog items that the team will commit to deliver, following which those items are broken down into tasks. Some teams using an adaptive approach will also break out and estimate time for refining or making ready large or complex items that are part of the current iteration or are next in line in a product backlog but have not yet been made ready—that is to say, sufficiently understood to begin development.

Despite these differences, there is still a need to allow time for business analysis planning as part of product development. No matter what type of life cycle is used, the thought process of planning for business analysis still needs to occur.

5.4.1 CONDUCT BUSINESS ANALYSIS PLANNING: INPUTS

5.4.1.1 BUSINESS ANALYSIS PERFORMANCE ASSESSMENT

Described in Section 5.7.3.1. A business analysis performance assessment summarizes what has been learned about the effectiveness of the business analysis processes and the business analysis techniques used in past efforts. As part of planning how to conduct business analysis for an upcoming effort, business analysis performance assessments may suggest ways to adapt business analysis processes and techniques to optimize their value in working with a group of stakeholders.

5.4.1.2 CHARTER

Described in Section 4.7.3.1. A charter formally authorizes the existence of a portfolio component, program, or project; establishes its boundaries; and creates a record of its initiation. A charter provides an initial understanding of scope and provides the context and rationale for a product development initiative. Together with the business analysis planning approaches (see Section 5.4.1.4), it becomes the basis for identifying which aspects of business analysis should be conducted and for estimating the level of effort involved.

5.4.1.3 ENTERPRISE ENVIRONMENTAL FACTORS (EEFS)

Described in Sections 2.2.1 and 2.2.2. EEFs are conditions, not under the immediate control of the team, that influence, constrain, or direct the portfolio, program, or project. The influences of EEFs are often considered when examining all the Knowledge Area approaches that are part of the business analysis plan to ensure its reasonability. See Section 5.4.1.4 for a listing of these approaches. Among the EEFs to consider are the following:

- Factors that may influence the formality of business analysis efforts and how and when those responsible for business analysis collaborate with their stakeholders include social and cultural influences and issues, stakeholder expectations and risk appetite, legal and contractual restrictions, and government or industry standards. Additionally, organizational culture, structure, governance, and geographic distribution of facilities and resources often have the greatest influence over how business analysis is conducted. Human resource management policies and procedures may impact the availability of individuals to be involved, along with the capability and skill level of the individuals selected.

- Factors that may influence the choice of techniques and tools in support of business analysis include the availability of tools to support business analysis, such as conferencing tools, modeling tools, and product requirements or backlog management tools, and any security policies, procedures, and protocols that may be associated with them.

- Factors that may influence or constrain the results of business analysis include enterprise architecture, organizational commitment to reuse existing products, and even the results of previous business analysis efforts. A commitment to reuse may lead some organizations to have templates for business analysis plans for different types of products or projects. Such templates contain frequently used approaches from all of the Knowledge Areas that a team may reuse as-is or reuse with modification.

5.4.1.4 PLANNING APPROACHES FROM ALL OTHER KNOWLEDGE AREAS

The planning approaches from the other Knowledge Areas can be consolidated into an overall business analysis plan. Along with the charter, they are the basis for considering the complexity and duration of business analysis activities and figure into any estimates developed that have business analysis effort associated with them. These components are:

- Stakeholder engagement and communication approach, described in Section 5.3.3.1;

- Elicitation approach, described in Section 6.1.3.1;

- Analysis approach, described in Section 7.1.3.1;

- Traceability and monitoring approach, described in Section 8.1.3.1; and

- Solution evaluation approach, described in Section 9.2.3.1.

5.4.1.5 PRODUCT RISK ANALYSIS

Described in Section 7.8.3.1. The product risk analysis includes the consolidated results from identifying and analyzing product risks. Higher-risk or more complex products and projects may require additional work effort to address the risks or the complexity.

5.4.2 CONDUCT BUSINESS ANALYSIS PLANNING: TOOLS AND TECHNIQUES

5.4.2.1 BURNDOWN CHARTS

A burndown chart is a graphical representation used to count the remaining quantity of some trackable aspect of a project over time. Burndown charts help visualize progress, stalled efforts, or backsliding where the remaining quantity of what is being tracked increases over time. Typically, teams working within an adaptive life cycle use burndown charts to track the remaining product backlog items in a backlog from iteration to iteration. Some adaptive practitioners track hours of work remaining or tasks remaining, although other adaptive practitioners would be wary that detailed tracking of hours or tasks could lead to micromanagement of the team's work.

For efforts using an adaptive life cycle, it is common for the work during early iterations to reveal a number of adjustments for requirements and the product backlog items with which they are associated. New requirements and product backlog items also tend to emerge in early iterations as more is learned about the solution. This additional work that is uncovered adds to the number of product backlog items remaining, which may cause a bump in the burndown chart. Such volatility is expected initially as part of using an adaptive life cycle; however, when the number of product backlog items remaining keeps increasing from iteration to iteration as development and delivery proceeds, or when progress flattens and stalls, there may be causes for concern. Thus, from a business analysis perspective, examining the trends seen in burndown charts could suggest modifications either to how business analysis is conducted or the amount of time devoted to it.

Figure 5-12 is an example of tracking remaining product backlog items in a backlog that might represent the normal course of events in a project using an adaptive life cycle, where there is initially an increase in the number of product backlog items remaining in early iterations, followed by a steady decrease.

5.4.2.2 DECOMPOSITION MODEL

A decomposition model is an analysis model used to break down information described at a high level into a hierarchy of smaller, more discrete parts. For estimation purposes, typical objects often analyzed with decomposition may include scope, work products, deliverables, processes, functions, or any other object types that can be subdivided into smaller elements. For product development efforts where discrete business analysis tasks and deliverables are estimated separately, decomposition models can be used to identify what needs to be estimated and ultimately sequenced into a business analysis work plan. Decomposition models are further discussed in Section 3.5.2.2 of Business Analysis for Practitioners: A Practice Guide.

5.4.2.3 ESTIMATION TECHNIQUES

Estimation techniques are used to provide a quantitative assessment of likely amounts or outcomes. Typical estimation techniques for an effort can include one or more of the following:

- Affinity estimating. A form of relative estimation, in which team members organize product backlog items into groups where each product backlog item is about the same size, or where team members use the notion of T-shirt size—e.g., small, medium, large, and extra-large—as an estimation scale.

- Bottom-up estimating. A method of estimating duration or cost by aggregating the estimates of the lower-level tasks. A decomposition model often identifies these lower-level tasks.

- Delphi. Used to support gaining consensus through anonymous estimating as well as to support decision making. For more information on Delphi, see Section 8.3.2.4.

- Estimation poker. A collaborative relative estimation technique in which there is an agreed-upon scale used for the relative estimates. Examples of scales include:

- The mathematical Fibonacci series: 0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34…and

- A modified Fibonacci series to which other numbers have been added. One such scale commonly in use is 0, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 20, 40, and 100.

Each person participating in estimation poker is given a series of cards with the agreed-upon scale. Team members typically will converge upon a reference estimate for one of their project's product backlog items, often using a Delphi or wide-band Delphi approach (see Section 8.3.2.4). The reference estimate is then used as a basis for subsequent relative estimates for each additional product backlog item that is to be estimated. Team members hold up cards that represent their estimates of the level of effort required in the context of their agreed-upon reference estimate, expressed within the chosen scale. Those who created the highest and lowest estimates explain their rationale, following which everyone estimates again. The process repeats until convergence is achieved.

- Relative estimation. A technique for creating estimates that are derived from performing a comparison against a similar body of work rather than estimating based on absolute units of cost or time. Relative estimation is similar, but not identical, to analogous estimation, which is usually based on historical data. For relative estimation, a team agrees on some way to represent an estimate for one product backlog item and then estimates other product backlog items in comparison to that agreed-upon estimate.

- Wide-Band Delphi. A variation of the Delphi technique where there is more communication and interpersonal collaboration to bring convergence to widely differing estimates that have been developed separately for the same task or product backlog item by a number of different individuals. Some organizations take a formal approach to wide-band Delphi, where all estimates are created anonymously by a team of experts and the members of that team collaborate to discuss the estimates and then re-estimate anonymously. Other organizations apply wide-band Delphi in an informal way, where those who created the highest and lowest estimates explain their rationale, following which everyone re-estimates. Irrespective of the approach taken, the process repeats until convergence is achieved.

5.4.2.4 PLANNING TECHNIQUES

Typical planning techniques may include one or more of the following:

- Product backlog. The product backlog is the list of all product backlog items, typically user stories, requirements, or features, that need to be delivered for a solution. Individual items in the backlog are estimated as part of selecting, in prioritized order, those items that the team is about to commit to deliver in an upcoming iteration. The business analysis effort for any product backlog item focuses on making sure that product backlog items meet the definition of ready, as described in Section 7.3.2.2. Making a product backlog item ready helps the team refine its business understanding of that item to the point where it has enough information to begin development. Although teams using an adaptive approach frequently allocate effort to make product backlog items ready, including time to look ahead at items that are likely to be selected for delivery within the next iteration or two, that time is typically not split out separately, but rather is considered part of the time needed to deliver the item. That said, some teams do account separately for additional time to refine the backlog. For more information on product backlogs, see Section 7.3.2.4.

In an adaptive life cycle, the timing of work done by a team to plan and commit to what is going to be delivered depends upon which adaptive approach the team uses. When using an adaptive approach, backlog management and kanban boards may be used as part of planning. For more information on backlog management, see Section 7.7.2.1. For more information on kanban boards, see Section 7.7.2.4.

- Rolling wave planning. This is an iterative planning technique in which the work to be accomplished in the near term is planned in detail, while the work in the future is planned at a higher level. From the perspective of business analysis, business analysts working as part of a predictive life cycle could be responsible for or could work with the project manager to create rolling wave estimates for business analysis tasks at intervals specified within the overall project schedule. For planning within an adaptive life cycle, rolling wave planning can be used at the release level to determine those features and functions for the current or next release. Similarly, within the context of rolling wave planning, progressive elaboration or further analysis identifies the specific features and epics to be included in the current release, and also incorporates new information into plans as the project progresses.

- Story mapping. A technique used in planning for projects that use an adaptive life cycle. Story mapping is used to sequence user stories, based upon their business value and the order in which their users typically perform them, so that teams can arrive at a shared understanding of what will be built. From the perspective of planning for business analysis, story mapping can help suggest when more effort may need to be spent on analysis. For more information on story mapping, see Section 7.2.2.16.

- Work breakdown structure (WBS). A planning technique for projects using a predictive life cycle. WBS is a hierarchical decomposition of the total scope of work to be carried out by the project team to accomplish the project objectives and create the required deliverables. Often, a WBS is subdivided by project phase and by component or deliverable within that phase. The WBS becomes the basis for creating a schedule that sequences the work that needs to be accomplished, based on estimates, priorities, dependencies, and constraints. For projects using a predictive life cycle, a WBS is typically created initially during planning and then revised at regularly scheduled intervals, such as phase gates. From the perspective of business analysis, business analysts would be responsible for the portion of the WBS that focuses on business analysis tasks.

5.4.3 CONDUCT BUSINESS ANALYSIS PLANNING: OUTPUTS

5.4.3.1 BUSINESS ANALYSIS PLAN

A business analysis plan, if formally documented, may be a subplan of the portfolio, program, or project management plan or may be a separate plan. It defines the business analysis approach through the assembly of the sub-approaches across all Knowledge Areas. A business analysis plan can include an estimation of level of effort for business analysis activities. It covers the entire business analysis approach, from stakeholder engagement to decisions about how to manage requirements. It is broader than a requirements management plan, which focuses on how requirements will be elicited, analyzed, documented, and managed. Whether formally documented or not, the business analysis plan provides a summary of the agreements reached for all of its components.

Whenever a written business analysis plan is a required document, it should be written in a manner that will be easily understood, because it will be reviewed and may need to be approved by key stakeholders.

For more information on business analysis plans, see Section 3 of Business Analysis for Practitioners: A Practice Guide.

5.4.4 CONDUCT BUSINESS ANALYSIS PLANNING: TAILORING CONSIDERATIONS

Adaptive and predictive tailoring considerations for Conduct Business Analysis Planning are described in Table 5-6.

Table 5-6. Adaptive and Predictive Tailoring for Conduct Business Analysis Planning

| Aspects to Be Tailored | Typical Adaptive Considerations | Typical Predictive Considerations |

| Name | Not a formally named process; performed as part of initial planning or iteration 0 | Conduct Business Analysis Planning |

| Approach | Some teams formulate their approach to business analysis planning by deciding how they will conduct discovery and backlog refinement. The level of effort needed for business analysis is rarely estimated separately from the time needed to design and develop or enhance the product. Instead, it is part of the overall planning for future iterations. |

Plan includes business analysis tasks, level of effort, roles, and responsibilities. Prior to beginning any elicitation activities, the business analysis plan is assembled using the component plans from other Knowledge Areas. The level of effort required for elicitation, analysis, traceability and monitoring, and evaluation activities is estimated. Approval or sign-off is obtained for the entire plan. |

| Deliverables | Rarely a separate deliverable. Some teams capture specific analysis tasks when creating the list of tasks for each iteration to a burndown chart or add something to the project charter about business analysis as part of authorizing the resources for the project. Some results of business analysis planning are reflected in the definition of ready. |

Business analysis plan, including work breakdown structure. |

5.4.5 CONDUCT BUSINESS ANALYSIS PLANNING: COLLABORATION POINT

The business analyst should build the business analysis plan collaboratively with key stakeholders to ensure engagement, achieve alignment, and attain buy-in. A plan that is constructed with the project team provides a sense of ownership to those involved and sets expectations by bringing awareness to how the work will be performed. The project sponsor is interested in aspects of the plan when additional costs to the project may be incurred, such as travel for workshop attendees and specialized business analysis tools required for the effort. For adaptive approaches, any light planning that is done will be performed as a project team.

Planning is an area where project managers and business analysts will find their roles overlapping, especially with respect to stakeholder identification and engagement, communication, risk identification, estimating, and development of work plans. The business analyst should work closely with the project manager to avoid redundancy of effort and to reduce the risk of inconsistent results.

5.5 PREPARE FOR TRANSITION TO FUTURE STATE

Prepare for Transition to Future State is the process of determining whether the organization is ready for a transition and how the organization will move from the current to the future state to integrate the solution or partial solution into the organization's operations. The key benefits of this process are that the organization can successfully adopt the changes resulting from the implementation of the new solution or solution component, and that any product or program component or overall program benefit anticipated for the solution can be sustained after it is put into operation. The inputs and outputs of this process are depicted in Figure 5-13. Figure 5-14 is a data flow diagram for this process.

Preparing for transition involves assessing the readiness of the organization to successfully transition from product development to operations and creating a plan to identify the requirements for making the transition successful. A transition readiness assessment addresses the ability and the interest of an organization to work within the future state or to use its capabilities. The readiness assessment is used to identify any gaps in readiness that are considered risks to achieving the end state, along with risk responses for addressing them. A transition readiness assessment may also incorporate the results from an organizational readiness assessment, which may look at an organization's overall readiness to incorporate any change and could include looking at the influences of the organization's EEFs and its organizational process assets. Organizational readiness can be measured against a maturity model, if one is available, so that an organization's maturity in terms of practices, procedures, and culture can be compared to that of other organizations. Comparing an organization's readiness to the readiness of similar organizations may reveal competitive opportunities or challenges that may be associated with the transition.

Preparing for transition to the future state identifies and utilizes transition requirements. Transition requirements describe temporary capabilities, such as data conversion and training requirements, and operational changes needed to transition from the current state to the future state. Transition requirements may also be discovered while modeling, defining and elaborating product requirements, or as part of a feasibility analysis—for example, when determining viable options.

Preparing for transition to the future state necessitates taking all the known transition requirements and readiness factors into account to support the creation of a plan for how the transition will occur. Frequently used strategies for planning a transition include:

- Massive one-time cutover to the future state;

- Staged release of the future state by a target segment, such as by region or by type of customer or type of employee;

- Time-boxed coexistence of the current and future state, with a final cutover on a specific future date; and

- Permanent coexistence of the current and future state.

No matter what strategy is selected, business analysis supports the creation of a transition plan, developed collaboratively with all the roles responsible for transition. The plan addresses all transition requirements, including the development of all the communication, rollout, training, procedure updates, business recovery updates, and collateral needed to successfully cut over and adapt to the future state. The transition plan is coordinated with other anticipated releases that enable the future state. It ensures that implementation occurs at a time when the business can accept the changes including any interruptions caused by the transition itself, and that the rollout is not in conflict with other in-process programs and project work. The transition plan may need to adjust as additional transition requirements emerge, including addressing deficiencies in organizational readiness.

The transition plan may contain or reference transition requirements expressed in whatever style is appropriate for the organization. The plan often includes a checklist of transition activities with no-later-than completion dates. In its most formal format, it has a prescribed schedule developed in collaboration with and managed by those responsible for project management and operations.

Successful product releases depend on delivering the solution with its expected capabilities and preparing the people who are going to use it. For some products, a successful release also depends upon having the operational environment set up or converted. For large or complex products, customer bases, or dispersed user bases, success may not be possible without a thoughtfully considered and executed transition plan.

Large organizations that use predictive life cycles typically have a very formal approach to transition to a future state. Yet, irrespective of organizational size, the execution of transition activities is an area where predictive and adaptive life cycles both rely on rigor and discipline and sometimes automation to transition a solution to its operational area, so that the transition will be as smooth and as seamless as possible. With that rigor and discipline in mind, transition plans are often initially considered early in a product's life cycle to gain a sense of what it will take to accomplish the transition.

5.5.1 PREPARE FOR TRANSITION TO FUTURE STATE: INPUTS

5.5.1.1 BUSINESS CASE

Described in Section 4.6.3.1. The business case describes pertinent information to determine whether the initiative is worth the required investment. The business case provides the context for the transition and a basis for prioritizing transition activities.

5.5.1.2 CURRENT STATE ASSESSMENT

Described in Section 4.2.3.1. The current state assessment is the culmination of the analysis results produced during the assessment of the current state. This assessment can be examined in conjunction with the solution design to identify differences between them, so as to consider how to handle those differences. Typical differences are areas where the solution design:

- Provides less functionality than the current state,

- Replaces current state functionality with new or improved capabilities, and

- Provides capabilities that previously did not exist in the current state.

5.5.1.3 PRODUCT RISK ANALYSIS

Described in Section 7.8.3.1. The product risk analysis includes the consolidated results from identifying and analyzing product risks. Higher-risk or more complex products and projects may require additional work effort to address the risks or the complexity as part of the transition.

5.5.1.4 PRODUCT SCOPE

Described in Section 4.6.3.2. Product scope is defined as the features and functions that characterize a solution. Understanding the product scope may be the basis for deciding how the transition should proceed and what special resources and coordination will be needed.

5.5.1.5 REQUIREMENTS AND OTHER PRODUCT INFORMATION