Why and How Should Feedback Be Given?

“. . . One of the most crucial organizational levers in the creation of cooperative working environments and collaborative teams is managers who coach and mentor others” (Gratton, 2008, p. 9).

“When it comes to guessing what others think of us, we often assume the worst” (Carole Robin, Stanford Graduate School of Business lecturer, quoted by Petersen, 2015).

“During a performance review, with its emphasis on your performance rating and salary increase, your boss is unlikely to really level with you about what you need to do to get ahead. . . . your boss will be careful about saying anything that might discourage a top performer” (Beeson, 2010).

From the employee perspective: Jane and Deniz sat together with other colleagues at the lunch table. “It’s about time to hear about our performance evaluations,” said Deniz. “Wonder what Aykut will tell us this time about our bad performance.”

“I don’t know,” said Jane. “But I’ve learned to expect the worst.”

From the manager perspective: Aykut sat at his desk, his head in his hands. “What do I do?” he thought. “How will telling them that they are good at their current jobs motivate them to do better? But the feedback trainer says that I shouldn’t tell them that they are poor performers, since that won’t motivate them. It worked for me in the past, even though I did have turnover problems. Telling people how good they are doesn’t make sense to me, but . . .”

Why Should a Manager Give Feedback After Evaluation?

Research shows that critical but kind feedback is a crucial part of Performance Leadership™. Appropriate feedback is a part of the Performance Leadership System designed to improve the performance of employees, the department, and the total organization.1 Feedback encourages employees to think about their performance and identify and develop their strengths, allowing high-performing teams and organizations to evolve.2

Weaknesses must be identified, of course, so that employees who complement each other can work together; however, the job should allow employees to use their strengths to fulfill departmental and organizational goals.3 Weaknesses are difficult, but not impossible, to improve. This may mean that a particular employee is not in the right position or in the right department—or even in the right organization. However, the manager must address these issues. For example, if one employee does not write well, another employee with a good eye for detail can help edit and clarify the report. A collaborative effort was used to develop and edit this book, and it worked extremely well. However, this means that the employee who does not write well must improve his level of writing skill.

Feedback is the process of analyzing and reviewing the performance of employees.4 The authors suggest that, although both positive and negative feedback should be given in most situations, the majority of feedback should be positive. The interesting thing about using negative feedback is that it reaches the fear areas of the brain, not the learning areas.5 When negative feedback is the majority of the conversation, the less likely the employee is to improve performance.

Positive feedback should always be given. When employees perform at a high level, acknowledging success creates trust and continued high performance.4 Positive feedback tells employees what they are doing right and gives them a sense of being valued by their managers. The more valuable employees feel, the more likely that their performance will be at a high level.

Feedback is an incentive that can cause the employee to engage her motivation. In fact, motivation cannot occur without feedback. Therefore, using feedback incorrectly may motivate the employees in the completely wrong direction.5 Providing employees with the appropriate feedback about their performance makes it more likely that their performance on the job will improve.6 Praising employees on good performance encourages them to be more interested in keeping up the good work and in achieving departmental and organizational goals as well.4

Employees and managers must have trust among members of a workgroup or department and between each employee and the manager for appropriate feedback to achieve full benefits. For mistakes to be corrected and performance to improve, employees need to be able to respectfully tell the truth to each other in an organization, without fear of reprisal. Without this, the same problems and mistakes will keep reoccurring.7

An American Management Association survey8 found that one frustration in performance evaluation identified by managers is a lack of managerial training in feedback and coaching. This is still a problem, according to interviews with nontraditional, working students, managers, and many others. Feedback must be given directly, not indirectly as it is in most cases.9 Clear two-way communication is essential to effective feedback; otherwise, feedback is a waste of time!

How Often Should Feedback Be Given? Is Annual Feedback Enough?

The annual or periodic performance appraisal is only one part of Performance Leadership; in the efficient and effective Performance Leadership System, it is done daily, weekly, and monthly as well. Having continuous feedback means that problems can be dealt with in a timely manner, instead of waiting for the annual review, when it might be too late to reverse problems that have arisen.10 These authors suggest that doing frequent feedback enables a complete evaluation to be based on a long span of time, instead of the most recent performance. Because the yearly evaluations are tedious and usually compressed within a short span of time, truly examining performance for yearly appraisal can be difficult, if feedback is only given sporadically or once a year.

Evaluations or appraisals should not be a surprise for employees, since they will have been given the goal expectations and frequent feedback on their achievement since their last evaluation. The appraisal is to allow managers and employees to plan for the next year or period of goal achievement. It can also give the employees the opportunity to discuss such things as performance standards, strengths and weaknesses, strategies for improvement, discussion of personnel decisions, potential promotion, and definition of regulations that deal with performance. In other words, modern human resource management practices consider periodic and frequent review to be part of employee development, as well as a mechanism and to improve communication.11 Self-evaluation is always recommended, so that the employee can provide missing information and identify environmental and training constraints to adequate performance.10

What Is the Best Way to Provide Feedback?

Managing performance requires bravery and the expression of confidence.10 Managers tend to avoid relevant feedback, making performance evaluations/appraisals unhelpful at best, and destructive in many cases. Few employees are perfect, but fewer are completely worthless—if their work is worthless, they should have been fired much earlier!

“The only task more difficult than receiving performance feedback is giving performance feedback.”12 The approach that the manager uses is the difference between success and failure in feedback.

“What’s meant to be a constructive and helpful discussion quickly gets lost once someone—even those who are sincerely interested in developing their talents and skills—hears critical feedback. . . . If negative feedback has the potential to discourage even the best performers and the most industrious employees, then managers need to be especially careful that what’s intendent as praise doesn’t get misconstrued as criticism.”13

Research over many years has found a definite link between active, two-way communication and improved and high productivity.14 It is essential that two-way communication is used during the feedback process, or the process will be harmful, rather than helpful.

Effective feedback includes knowing subordinates well.10 Managers must ask questions about the subordinate and the goals that he wishes to achieve, so that he can see that his goals are aligned with organizational goals. Managers must prepare for feedback sessions, just as though preparing for an employment interview or a presentation. Managers should know their employees’ past performance and personalities, if the feedback session is to be effective and used as a tool for positive reinforcement and employee development.

What Are the Steps in Giving Feedback?

There are specific steps to giving feedback about the appraisal process. However, yearly evaluations are not the only time that feedback should be given—this needs to be emphasized! Good managers look for opportunities to give positive feedback in public and negative feedback in private. Giving both types of feedback on a regular basis means that the annual review, appraisal, or evaluation is not a surprise to the employee. It reduces the potential for Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) action and other legal ramifications as well.

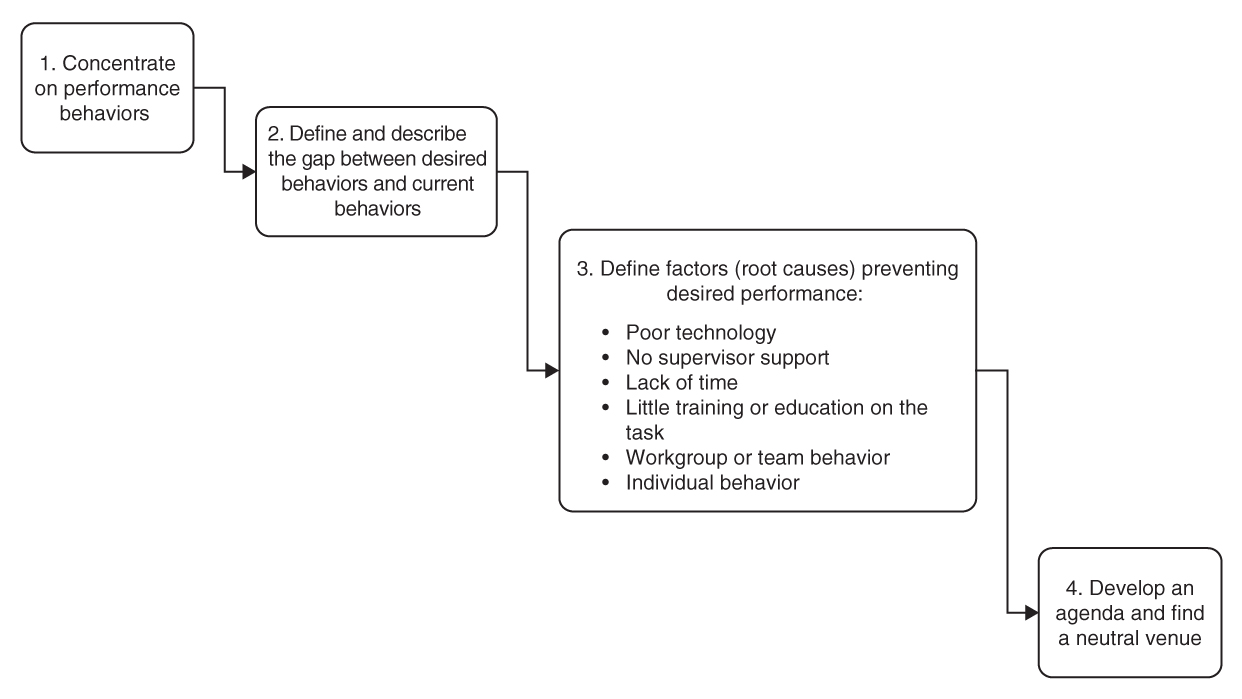

Bernardin, Orban, and Carlyle10 developed a list, and there are other good suggestions adapted from research and practice. Bies15 identified three separate parts: preparation, delivery, and transition. The first four steps are preparation and should be done by the manager before involving the employee, as shown in Exhibit 7.1.

Exhibit 7.1 Preparation for Feedback—Steps to Take before Involving the Employee

The preparation stage includes those steps that help prepare for the evaluation/appraisal.15 This stage and these steps control the success of the other stages in the process.

1. There are no bad employees, just substandard performance. Concentrating on performance behaviors and/or results creates effective feedback. Performance is the only thing that can be measured by a manager.13

2. Define and describe the gap between present and expected behaviors. This gap analysis allows the manager to determine the difference between excellent, average, and substandard performance. Doing a SWOT (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, threats) analysis of the employee helps in this step. A suggestion from The Center for Creative Leadership16 is to use SBI: Situation—describe the specific situation; Behavior—describe only the behavior because you can’t know what the other person was thinking; Impact—describe reaction to the specific behavior, that is, what happened because of the behavior.

3. What constraints affect the performance? In other words, managers must look at the environmental and resource impacts of the links between attitude and intention and between intention and behavior, as illustrated in Exhibit 2.1.

Remember that people do not work in a vacuum. As mentioned in the chapter on Motivation, there may be environmental circumstances that have actually caused the failure, such as lack of training or lack of resources, including time and technology. There might be workgroup or team behaviors that are getting in the way, that are not necessarily the fault of the employee being evaluated. Another employee may cause a bottleneck to occur in the process, due to a faulty process. All of these alternative explanations need to be thoroughly explored.

4. Develop an agenda in writing. Think about ways that the gap in actual and desired performance might be addressed. Find a neutral location to do the evaluation. This should not be a case of calling the employee into the manager’s office, as though she is an unruly child, but instead a discussion about performance and development.

5. Inform the employee that you will be talking with him about his performance, and give the date, time, and location. Ask the employee to consider how he would evaluate or appraise his performance before the meeting, so that he can come prepared. The employee should be given any paperwork that the manager has used to make his initial evaluation of the employee’s performance—any metrics, comments, SWOT analysis, or other information that has been used to make the judgment.

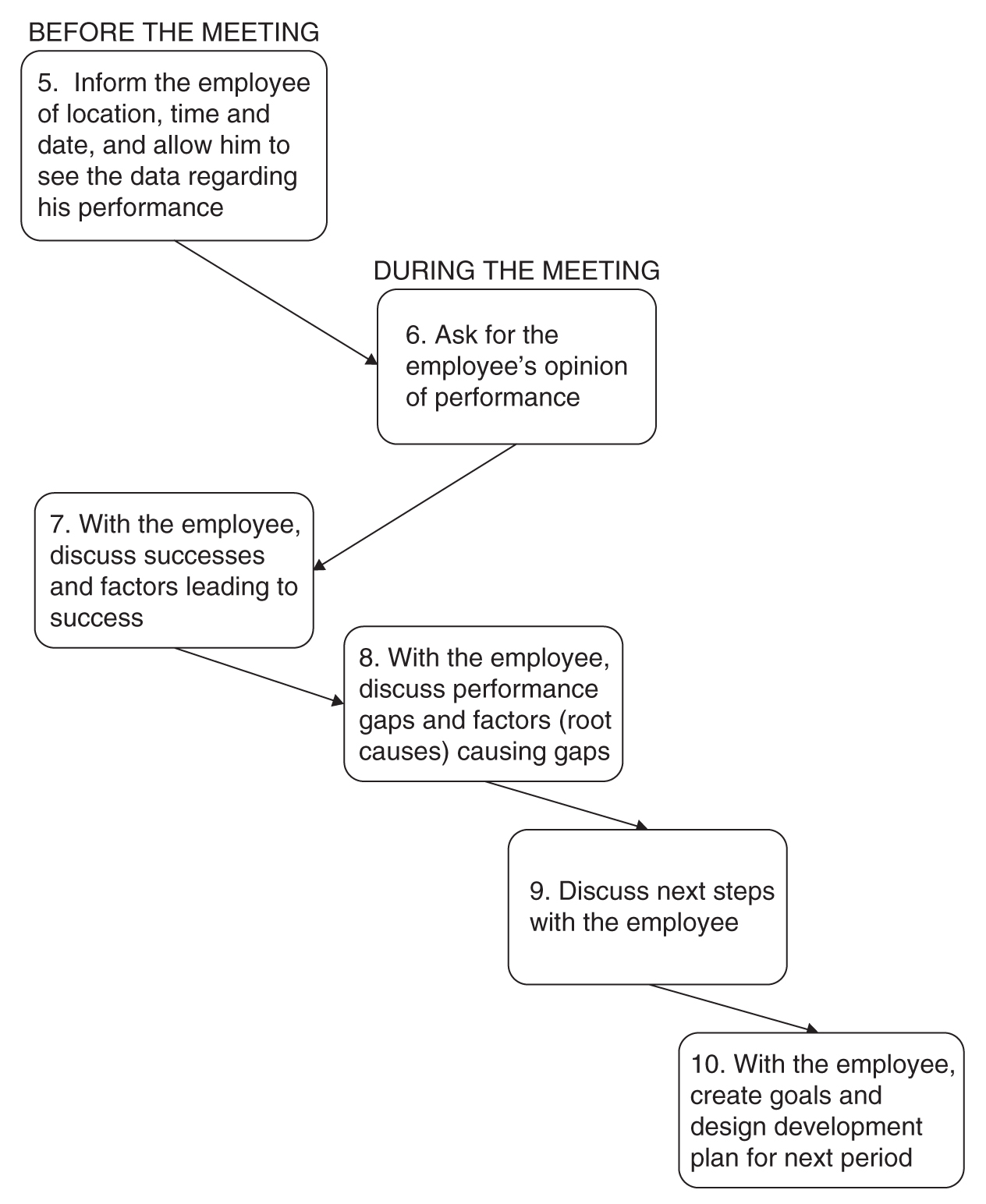

Delivery, using oral and written feedback in discussions with the employee, is the next stage.15 When giving feedback, it is always helpful to be as positive as possible, depending upon the circumstances. Exhibit 7.2 gives an example of the next steps of feedback communication. The words and phrases of “ask,” “discuss,” and “with the employee” used in the following steps were carefully chosen. Communication, by its very nature, is two-way. Evaluation feedback should not be a manager monologue, but instead a dialogue where the manager keeps an open mind until all of the facts are available, including those from the employee perspective. It is a discussion of the employee’s performance, and appraisal will not be a surprise, if the employee has been advised of what success looks like and given resources to achieve it.

6. Ask the employee what she thinks of her performance, overall. Has it been successful overall, or have there been problems and hiccups along the way? This will give the manager an idea of the employee’s ability to critically examine her behavior and consequences.

7. Discuss the employee’s successes. Be honest and truthful about the successes—don’t insult the employee by pretending that failures or omissions were successes. Discover why the employee was successful or thought that she was successful. It is possible for the manager and employee to have differences of opinions on success, and it is always well to determine the employee perspective before giving your own part of the open-mindedness needed in management and leadership. Was it because she was interested in the task? Was it because she had needed resources and assistance?

Note: If the only thing that you can find to praise is attendance, then do so. However, the outcome of an evaluation with no good performance should be employee termination! And it should not have waited until the annual evaluation/appraisal!

8. Discuss perceptions of the employee’s gaps between expected performance and current performance. Using the job description, explain what is seen when analyzing the gaps between excellent performance and his performance. Describe the effect of these gaps on organizational and/or departmental goal achievement.

Feedback is a discussion—two-way communication and active listening on the part of the manager is required. The manager informs the employee of the gaps, and together they analyze why the gaps occurred. This is not “giving excuses.” This is finding solutions to problems that the employee is encountering in performing his work—not issues of his behavior. Replacing an employee is not an option if there are factors preventing successful performance—the next employee will likely have the same difficulty in successful performance.

The next stage is transitional.15 These steps help move the discussion to the next level—how the employee can improve and develop skills. This is where education, new experiences, and potential training are discussed. Before leaving the feedback session, be sure that employees understand why, what (specifics), how, who to work with, and when the improvement or task should be accomplished. This stage involves the SMARTER goals and will go a long way to improve productivity (see Chapter 5).

9. Discuss the next steps that will be taken or that the employee is expected to take. Inform the employee of his future prospects within the company, positive and/or negative. Can the problems that the employee faces in successful performance be overcome or eliminated? For example, if there is not enough time to do it, can the time be extended? Is the time frame for performance reasonable, but the training is needed? Is the training available in-house? Are there too many interruptions in the performance of a creative task, and the employee needs a quiet place to complete it? Do the employee’s interpersonal behaviors prevent success? If this is a work group or team compatibility problem, what actions should a manager take to solve it? The root causes of the low performance have been determined by the steps above, and training should be based on those root causes.

10. With the employee, set written SMARTER goals and design a written development plan. Development plans help orient the employee for those skills and knowledge that she may need to learn if she is to achieve the performance goals.

Exhibit 7.2 Evaluation Steps Involving the Manager and the Employee

Goals must be specific, measurable, achievable, relevant/realistic, time-dependent, ethical, and resourced (SMARTER goals, Exhibit 5.1) if they are to be achieved. Identify skills, abilities, and resources needed with the employee’s participation. Effective goals are made jointly, not only by the manager. Setting specific goals can cause employees to be motivated to display positive behaviors.17 When setting developmental goals, be sure that there are subjective and contextual performance measures as well as numerical and task performance measures. Having only numerical goals focused on the task will decrease quality.18

Remember to focus on strengths from your and the employee’s analysis of her SWOT results. Base development on building strengths and neutralizing or minimizing weaknesses. Weaknesses should only be a part of a development plan where it interferes with the performance of the job. For example, if a professor has stage fright but is expected to teach and give seminars, her weakness must be addressed. In the same way, if a person must write well to perform a major part of the job, then writing must be addressed as a communication weakness or a method must be developed to remove this part of the job from the position. Removing the weakness, in this case, transferring the writing to someone else, will not be productive. It will not allow the subordinate to develop skills, knowledge, and abilities that will allow him be more productive in future.

Improvement plans should always be given in writing, for several reasons. The improvement plan should be used to help develop the goals for the next performance cycle. Documentation of these events prevents the manager from forgetting to check on the results frequently. In addition, employees report being more satisfied when there is a written component to the process than when there is only oral feedback.19 It also helps with organizational and departmental continuity if the manager leaves the position. Written improvement plans are more likely to help employees figure out the deficiencies and reasons for low performance, as well as support their strengths. It is also a key discipline step.

Feedback doesn’t have to be complicated, frightening, or negative. Most fear comes from the unknown, so practice helps. If there is some fear that the employee will react badly to the performance feedback, it is likely because the performance evaluation was seen as a gotcha appraisal and not a true appraisal of the work.12 The human resource department is available to help with these issues, and it is helpful at times to have the human resource manager or another manager sit in on sessions where you have some fear of misunderstanding or retaliation. Having another person helps improve perspective.

Following the Performance Leadership System design is not difficult, and implementation of this system that requires employee input results in high trust between employees and supervisors. It is clear from communication and from feedback research that miscommunication is generally caused by perceptual noise, that is, the feeling of injustice within procedures. Having procedures that involve the employee in determining accurate measurement of tasks comprising the job results in feelings that the procedures are just and appropriate, which eliminates most perceptions of injustice, an issue that is discussed in Chapter 8.

Example 7.1

“I really wish that there was some way that we could convince Fredo could give us some sort of written evaluation when we have our annual review,” Jose said to Henri as they worked stocking the shelves in the Intensive Care Unit. “It seems that I just listen to him talk about my performance and sign the paperwork, but I get nothing afterward.”

“I know what you mean,” said Henri. “After my work on the special project, he said that I took a difficult job and did it very well. But there was no raise for me last year, and I still don’t know why. Fredo said that he can’t tell me.”

What Is the Problem Here? How Can Performance Leadership Help in this Situation?

Feedback is a crucial part of the Performance Leadership System. By being transparent about the way that decisions are made and what those decisions are, motivation can be increased, even though the decisions may not be exactly those that the employee wants. However, if the CEO is seen to get a very large raise while the frontline employees get little, or usually nothing, there is no incentive technique in the world that will help.

Too much is made of the secrecy of the decisions surrounding raises, bonuses, and wage rates in organizations. Research into the theory of organizational justice finds that people are more interested in fair processes (procedural justice). They will accept distribution decisions (distributive justice) if they feel that the way the decisions were made is fair. This is very culturally dependent, but on the whole, organizations spend too much time on trying to keep secrets when transparency would produce more organizational commitment and loyalty.

Example 7.2

“I didn’t get a raise last year,” said Yvonne. “I doubt if I’ll get one this year. And I don’t know why. What did you get last year?”

“I got a one percent raise last year, hardly worthwhile, but at least some recognition,” said Rita. “I don’t understand why you didn’t get a raise. Your performance was better than mine in the first part of the year. We only came out equal during the last few months.”

“It would be great if they would be up front with us and what we are doing,” replied Yvonne. “But I guess that would be too good to be true.”

What Is the Problem Here? How Can Performance Leadership Help in this Situation?

Raises are a big deal to most people, as are performance evaluations, held annually in most organizations. Feedback is crucial to continual employee effort toward organizational goals. But without some definite feedback, no one knows how well or poorly they have done. And when managers use chicken management as their main operating mode, they are unwilling to be precise. This is why layoffs are often given first to those that other employees know should have been fired anyway—the deadwood, as many managers call them.

Because raises, bonuses, and promotions are often based on performance evaluations, it is essential that employees know where they stand, and not just on an annual basis. As emphasized in this book, evaluations/appraisals should never be a surprise. That way, an employee can make needed corrections during the year, instead of at the end of the appraisal term.

Example 7.3

This exercise may be useful in thinking through the difficulties in feedback. Think about the evidence that demonstrates your answer to the question.

Questions For Evaluators or Managers

If the statement is true, write T next to the number. If the statement is false, write F. If undecided, write U.

1. Giving feedback to employees is an important part of my job.

2. I believe feedback can improve an employee’s performance.

3. I will not lose my employee’s loyalty if I give him negative feedback.

4. Giving feedback to employees is a valuable use of my time.

5. My feedback is frequent, accurate, and kind.

6. I give effective, constructive feedback.

7. I am comfortable giving positive feedback.

8. I give negative feedback when needed.

9. I plan sufficient time each day/week to give employees feedback.

10. I always try to improve my ability to give effective, constructive feedback.

11. I always use evidence and examples while giving feedback.

12. I understand how to use two-way conversations in feedback, along with active listening.

(Adapted from Mone & London, 2010, p. 86).

1. Aplin, Schoderbeck, & Schoderbeck, 1979.

2. Gratton, 2008.

3. Buckingham, 2015.

4. Harms & Roebuck, 2010.

5. McManus, 2001.

6. DeNisi & Kluger, 2000.

7. Hauck, 2014.

8. Krug, 1998.

9. Asmuβ, 2008.

10. Bernardin, Orban, & Carlyle, 1981.

11. Aguinis, 2013.

12. Cleveland, Lim, & Rich, 2007, p. 170.

13. McGregor, 2014.

14. Camden & Witt, 1983; Downs & Hain, 1982; Hellweg & Phillips, 1982; Jain, 1973; Lewis, Cummings, & Long, 1982; Papa & Tracy, 1987; Snyder & Morris, 1984.

15. Bies, 2013.

16. The Center for Creative Leadership (http://www.ccl.org/leadership/pdf/community/SBIJOBAID.pdf).

17. Ordonez, Schweitzer, Galinsky, & Bazerman, 2009.

18. Waltruck, 2012.

19. Clausen, Jones, & Rich, 2008.