What Is the Performance Appraisal Process?

“During my first performance review at my first-ever job, my manager told me that the ratings system operated on a five-point scale—except, it kind of didn’t. No one, she told me, was ever rated at one, and it was also rare for employees to receive twos. But no one ever got fives, either, meaning that most employees were considered average to just-above-average, collecting a bunch of threes and fours” (Dahl, 2015).

From the employee perspective: “Uh oh, performance review time,” Danny said to Jim, as they walked from the office to their cars after work. “Wonder what our supervisor will find to complain about this time?”

“No telling,” Jim said. “Margaret, the CEOs secretary, said that there was little money for raises this year.”

From the manager perspective: Ali turned to Ece as they walked from the manager’s meeting. “How am I going to tell the staff?” he said. “If there is little money, they will want us to lower the employee’s evaluations again. How can I do that?”

“I don’t know,” replied Ece. “My department runs well because the employees are well trained and motivated. This will totally strip them of any motivation to stay and work hard. All of my good people will go.”

Where Does Evaluation Fit in Performance Leadership™?

Performance evaluation is a key part of the Performance Leadership System. Developing an instrument to measure performance does not have to be difficult, and it doesn’t have to be lengthy. It is based on the job description and job specification that were developed from job analysis. Having a clear understanding of performance helps determine what to measure.

There are different ways to measure performance, but all should take into account the work environment. Each measurement tool should take into account both task and contextual performance behaviors. Cultural differences also played a role in measurement. For example, firms with U.S. employees are likely to measure and reward individual behaviors. In other countries, group performance may be the preferred behaviors, so measurement and reward systems should reflect this difference.

What Are Different Approaches to Measure Performance?

Aguinis1 suggests three approaches to measure performance: trait, behavior, and results approaches. The differences between these three approaches are outlined below.2

The trait approach is not recommended, and the reasons are given below. Most managers and human resource managers prefer the behavioral approach or the results approach, depending on the circumstances. The behavioral approach is best when processes are emphasized by the organizational or departmental goals. The results approach is concerned with the results, and takes less time than the behavioral approach. A newer approach is the 360-degree appraisal format. The trait approach is discussed below, and the three other approaches are discussed in sections following. Taking personal and environmental criteria into account, the manager must choose which type of measurement to use.

Trait approach. The trait approach measures and evaluates abilities of personality, and often means measuring intelligence and conscientiousness.3 It is not recommended for general use. A person possessing intelligence may not use it appropriately to achieve organizational or departmental goals. It does not take into account specific situations, such as workplace climate or availability of resources to do the job. In addition, traits are generally stable over a person’s lifetime; without extensive effort on the part of the employee, they are unlikely to change.4 Trait approach is useful only when reallocation of human resources is anticipated, such as during strategic structural reorganization, but even that is open to some disagreement.1

What Is the Behavioral Approach and How Is It Used?

The behavioral approach is focused primarily on the job specification and measures competencies, that is, the skills, knowledge, and abilities essential to achieving organizational and departmental goals.5 These knowledge, skills, and behaviors drive high performance.6

The behavioral approach is useful when the processes used to achieve a goal are as important as the goal itself. Grote2 advises the use of the behavioral approach when:

• The employee has no control over the results;

• The correct behaviors may not lead to the desired goal; or

• The goal will not be seen for several months or even a year or more.

For example, an employee may experience continual machine breakdowns, resulting in no production. His lack of production may not be a result of his behavior. Another case is when events impact results beyond the control of the employee; this would be the case of salespeople and economic downturn. It would be evident that fewer sales would be likely, regardless of the skills and abilities of the salesperson.

When the process of checking a list does not usually determine the result but is seen as a critical behavior, such as the pilot’s checklist before flight, the behavioral approach would be preferred. Another use of the behavioral approach would be when an employee works on a part of a very large goal. She might be involved in developing a new drug, which takes years to complete. In each of these cases, the behaviors an employee exhibits are more important to evaluate than the results. And in these cases, it is probably better to do appraisals more frequently than once a year to maintain positive morale.1

Examples of competencies are knowledge of management theories, knowledge of accounting, oral communication skills, presentation skills, creative thinking, leadership, and interpersonal abilities. There are two types of competencies: differentiating and threshold.1 The differentiating competencies are those that create standard and outstanding performance. Threshold competencies, on the other hand, are minimum requirements for success on the job. The differentiating competency in project management is the ability to manage projects, while whereas a threshold competency would be change management, which in turn requires relationship skills, operational skills, and understanding of motivation.7

Each competency is broken down into the behaviors required. These are called indicators. We don’t measure the competency itself; the indicators tell us if the competency exists and to what extent.1 There can be several different indicators for each competency. When the indicator is displayed as behavior, we can assume that the competency exists. For example, the competencies of leadership are person orientation (also called consideration) and task orientation (also called initiating structure). Suggested indicators for the person orientation competency include (a) Respect, (b) Encouragement, (c) Support, and (d) Personal knowledge of subordinates.7

From this example, we can see that, to describe a competency, we must first describe the competency and give a description of specific behaviors that are indicators of successful and unsuccessful demonstration of those competencies. It is also necessary to develop a list of development suggestions for the employee group.2 Using the example of leadership and the consideration competency, we can see that leaders who only speak to employees about tasks would not demonstrate competency. To develop this competency, the manager could suggest that her subordinate (the middle manager) ask employees regularly how their lives outside work are going.

Unlike the results approach, the behavioral approach uses data from those making a judgment about the presence of the competency, called raters.1 Raters are usually the direct supervisors but can include the employee, customers, peers, or subordinates.

These data are used in two types of systems: comparative and absolute.1 A comparative system measures one employee’s behaviors against another’s. Simple rank order is the most common, and employees are ranked from worst performer to best performer. Another type is forced distribution, where employees are ranked according to required percentages. For example, GE under CEO Jack Welch used this system, where 20% of employees in a specific unit were considered to be exceeding expectations, 70% as meeting expectations, and 10% as not meeting expectations.1 Using this method can be beneficial, because the ratings are easy to explain.

A comparative system assumes that each unit has employees performing highly, poorly, and in-between, which may not be true. There are units where all members perform very well, and there are units where everyone performs below standard. In some industries, such as athletics, entertainment, and academia, a small number of people are responsible for the best results, such as scoring, performance, and number of papers published.9 In addition, the system can discourage contextual performance. Some employees may decide not to help others, thinking, “Why should I help them do their job and move them up in the rankings?”

Limitations to this system of comparing employees can be considerable and create morale problems. The rankings are not specific enough, so the employees do not receive specific feedback about their behaviors. The ranking becomes more important than the work itself.10 For example, an employee may just repeat the same process that gained him high rewards in the last evaluation, but ignore the rest of the duties, which might be central to his job.

Comparing someone who is very diligent and skilled at one set of needed tasks with someone who is very diligent and skilled at another set is difficult at best; it is not considered a best practice in management. In addition, someone who has met the expectations and goals of the job may be rated in the lower 10 percent because the other members achieved the goals and expectations at a higher rate.

An absolute system does not compare one worker with another.1 This approach sets up a scale of expected behaviors resulting from the job description discussed in Chapter 4, and the employee has exceeded, met, or failed to meet expectations. The absolute system is easier than the comparative system to administer, as it does not require managers to try to compare apples with oranges.

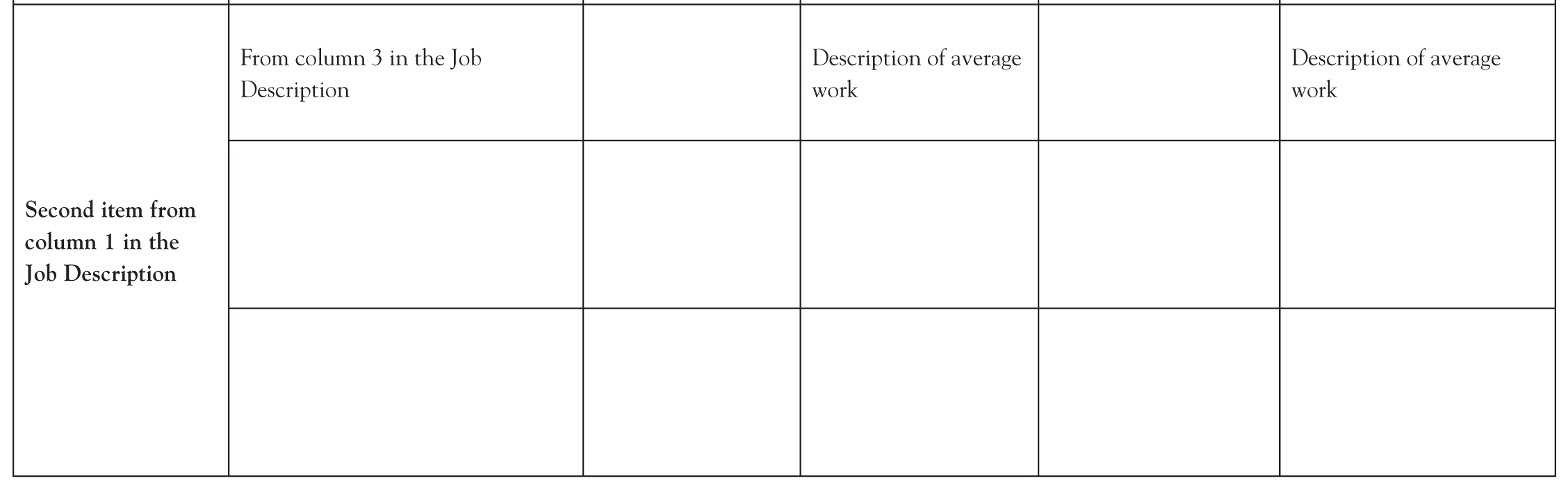

Examples of Behavioral Approach tools are shown in the exhibits. Exhibit 6.1 shows the template for behavioral evaluations, and Exhibit 6.2 is an example of that template, using the Job Description from Exhibit 4.2 as the background for the evaluation measure. Exhibit 6.3 is an example of a critical incident behavioral system that requires close and continuous monitoring of performance, which is not always feasible. Critical incident monitoring is useful in areas where there are ongoing problems or where the critical nature of the tasks requires that the manager constantly be in touch with how the work or a particular task is proceeding.

Behavioral Tools for Evaluation

Behavioral Evaluation Example

(Using the first item in the job description example in Exhibit 4.2)

Critical Task Behavioral Monitoring System Example

Using partial example from a front-line customer service representative. Attempting to use objective measurement of critical tasks.

What Is the Results Approach and How Is It Used?

The results approach does not consider the processes used to generate the result. It is solely focused on measuring defined outcomes and can often appear more objective than the other methods.2 This approach should be used when2:

• Results of behaviors are seen to be related;

• Employees are skilled and have the knowledge to do the work; and

• Different behaviors can have the same or equally positive results.

Sometimes, tasks or duties performed in specific order are necessary, such as in repetitive tasks and assembly line work. In this case, timely and efficient actions at a designated standard of quality would be the correct results to measure. In cases where workers are skilled, results are the best measure. Using the results approach when there are various ways to do the job encourages creativity and innovation.

The results approach also uses the job description, discussed in Chapter 4, to develop performance measures of outcomes. Goals set previously are analyzed with the results approach. These measures become the standard against which employee results are measured. They identify performance that is acceptable by using such things as cost, quality, quantity, and time. This allows employees to align their goals with those of the organization or department. This measurement approach supports management by objectives. However, care must be taken to carefully consider the desired results.11 One of the problems identified with the 2008 financial crisis is the results that were linked to rewards. In emphasizing the quantity of loans processed, the quality of those loans was eroded.

What Is 360-Degree Evaluation?

One fad at the time this book is written is 360-degree evaluation, also called multisource feedback. This is where a significant representation of the subordinates (if any), peers, and managers are given a form to assess the appraised employee’s performance.12 It includes customers and others inside and outside the organization that comes into close and regular contact with the appraised individual. The employee to be appraised also completes the evaluation. After completion of the various evaluation forms, the manager pulls them together and decides the final evaluation, based on the results.13

Results have not been positive. A critical requirement of effective 360-degree evaluation is trust. 360-Degree feedback encourages trust and shared accountability, which directly influences performance, especially in team-based, self-directed, and task force environments.1 However, this type of evaluation is not recommended, unless the entire organization has had comprehensive training in the process,15 and the top management team provides coaches to help recipients evaluate their feedback from the process.16 Taking subordinate and colleague opinions into account in an evaluation can be a good idea, but formalizing this process can be a nightmare for the employee, manager, department, and organization.17 Limitations include such things as the lack of a frame of reference to make judgments and the fact that most of the observer’s ratings will be based on memory, rather than on the day-to-day interactions with the employee.17

One of the main problems is the different expectations of observers, who do not have access to the employee’s job description.18 Without training and verification, the process can be seen as unfair and inequitable. For example, an employee who has been recently rewarded is more likely to say positive things, while an employee who has been disciplined is more likely to be negative. Colleagues in continual contact with the person being evaluated are more likely to have a complete picture of performance, but they are not the only one asked. If you ask those who are not continually working with an individual to evaluate them, the response will be hit or miss, in terms of accuracy. Subordinates often fear that somehow their managers will discover which appraisals they wrote.18 One of the authors of this book was rated by this method when working in industry; it was poorly done without training and very distressing for the recipients of the evaluation, eroding a great deal of trust in management.

Why Is the Performance Leadership System Important in Appraisal/Evaluation?

As discussed in the previous chapter, defining performance measures in advance on the job description allows the employee and manager to determine how well the results have been achieved as the evaluation period progresses, instead of only at the time of evaluation/appraisal. When setting measures, it is necessary to consider the action, the result anticipated, a timeframe, the quality, and the quantity1. Measures on the job description reflect successful performance. Once the measures for excellence are set, then further measures for average and unacceptable performance can be determined for the purposes of appraisal/evaluation. The measures should not be based on an individual worker’s performance, and they must be reviewed regularly. Measures should be both objective (tangible) and subjective, particularly when measuring the contextual performance required.

The job description allows goal setting to proceed, because it clearly states how the specific job relates to the overall organizational and departmental goals. Having this information, along with the tasks and success indicators for the job, the manager and the employee plan the direction and clarify outcomes of the job. In itself, this knowledge can be very motivating for both the manager and the employee. It shows a great deal of trust in the employee’s potential, and allows the employee to communicate concerns and resources needs to the manager. Goal setting was previously discussed in Chapter 5.

Do I Really Have to Write All of this Down?

Documentation is an essential part of the manager’s job. Without documentation about employee performance, nothing can be done to reward or discipline the employee.

“I one time got a call from a manager who was ready to fire an employee on the spot. He claimed that the employee regularly underperformed, was often late and was disrespectful toward coworkers. I did what most HR people would do and grabbed the employee’s file in order to look through the history of warnings and reviews. There were no warnings and all the reviews told the story of an excellent employee who did not have any problems. When I questioned the manager, he said, ‘Well, I didn’t want to give the employee a negative review because that might have made him ineligible for an increase.’”19

The manager’s dilemma is clear, since employees are generally inherited from previous managers, and often, what you get is a mixed bag. When first starting as a manager in a new area, looking at the human resource management files and the former manager’s files can give a “heads-up” to any potential problems. But, if a manager inherited the employee discussed above, she would have to restart the discipline process from the beginning. This essentially describes chicken management—the manager is unable or unwilling to do those things that she has been authorized and delegated to do.

Now That the Employee Measurement Is Complete, What Is Next?

The next step is to communicate the findings of the measurements to the employee. Organizations using the Performance Leadership System create incentives by generating trust and correctly using the communication loop. The communication loop only operates where there is trust. Most managers are aware of the need for communication, but are confused when communication does not work in an environment of distrust. Feedback is a crucial part of Performance Leadership and is discussed in Chapter 7.

Example 6.1

Mary sighed. “Evaluation time,” she thought. “I wonder what John is going to find wrong with my performance this time. No matter how hard I try, he always finds something to use to mark me down. It is just a game to him. Does he know how much this irritates me? Does he know that I’m looking for another job? Three years of this is enough.”

“What am I going to do?” thought John. “As a manager, I know that the top management team wants an organization that is a five out of five, but they tell us that most of our employees should be rated as three out of five. What a joke! How can we have a five organization if most of our people are threes? Does the top management know how demoralizing this is for me—not just the employees? Wonder if they know that I’m looking for another job?”

What Is the Problem Here? How Can Performance Leadership Help in this Situation?

This is a game that is played in many organizations by the top management team. To have an excellent organization, you must have excellent people. But excellent people may require raises, which the organization cannot afford. This is the catch-22 for managers, when the top management wants to play chicken management—using a poor evaluation as a reason not to give a raise. In our experience, it is better to be honest with the evaluations, even if the raises across the board must be smaller.

In a perfect world, the performance appraisal/evaluation would be a measure of performance and a tool for personal and organizational development, not for deciding on raises. However, there is no perfect world, and all organizations use these tools for multiple purposes.

Notes

1. Aguinis, 2013.

2. Grote, 1996.

3. See for example, www.kenexa.com and www.appliedpsych.com

4. Smither & Walker, 2004.

5. Levenson, Van Der Stede, & Cohen, 2006.

6. Jones, 1995.

7. Kendra & Taplin, 2004.

8. Judge, Piccolo, & Illies, 2004.

9. O’Boyle & Aguinis, 2012.

10. Holland, 2006.

11. Schweitzer, Ordonez, & Douma, 2004; Waltruck, 2012.

12. US Office of Personnel Management, 1997.

13. Atwater, Brett, & Charles, 2007.

14. Smither, London, & Reilly, 2005.

15. Luthans & Peterson, 2003; Seifert, Yukl, & McDonald, 2003.

16. Hazucha, Hezlett, & Schneider, 1993; Smither, London, Hautt, Vargas, & Kucine, 2003; Smither, London, Reilly, Flautt, Vargas, & Kucine, 2004.

17. Moses, Hollenbeck, & Sorcher, 1993.

18. Atwater, Brett, & Charles, 2007; Brutis & Derayeh, 2002.

19. Hammerwold, 2015.