How Is Management Success Created?

“Management style [means] a manager gives clear directions and actually stays pretty hands-off, but is ready and available to jump in to offer guidance, expertise, and help when needed.” (http://www.forbes.com/sites/dailymuse/2014/10/16/how-to-answer-whats-your-management-style/)

“Leadership is less about your needs and more about the needs of the people and the organization you are leading. Leadership styles . . . should be adapted to the particular demands of the situation, the particular requirements of the people involved, and the particular challenges facing the organization.” (http://guides.wsj.com/management/developing-a-leadership-style/how-to-develop-a-leadership-style/)

From the employee perspective: Sally’s1 stomach was full of butterflies. “Annual review time,” she thought. “Once again, someone who knows nothing about my job will try to tell me what I’m doing wrong. When can we stop pretending that this is doing any good?”

From the manager perspective: John looked at the calendar and sighed. Twenty performance appraisals due to the human resource department in a week. In the cafeteria, he saw Alicia, and sat with her to eat his sandwich. “I just don’t know how I’m going to get all of those appraisals done in time,” he said. “I have to do all of the measurements, write the evaluation, and then talk to each employee, added to my regular duties that already keep me working overtime. How have you managed over the 10 years you’ve been here?”

“It is the training that they gave me, but they don’t do it any longer. Performance leadership is a comprehensive, organization-wide management system, and appraisals are just a part of the whole system,” Alicia replied. “All managers need training on the entire system, not just on how to do appraisals.”

Why Are Management and Leadership Styles an Issue?

How managers approach employees is important. At its essence, management style is an exhibition of the attitude that the manager has toward the employees and the goals of the department and/or organization.2 Management style is demonstrated by the way that the manager treats employees and the work activities of the department or organization.3 It might be formal, democratic, paternalistic, participatory, or other styles suitable to the way that the manager views the employee group and the goals to be achieved. It is rarely defined in the research, but many of the general books and textbooks on management use this phrase in this way.

Management styles vary, and some are dependent upon the situation. Unfortunately, this often leaves employees uncertain about their level of performance or their status in regard to continuing employment. Some managers are aggressive, believing that employees are lazy and looking for ways out of work. Others believe that employees are willing to work and they need direction to be successful. One of the most successful ways to manage employees is to be concerned about their welfare and to point their effort toward goal achievement, rather than micromanaging them.4

Why Should Performance Leadership™ Be a Management Style?

Performance Leadership as a leadership style is a new concept presented in this book. When concentrating on Performance Leadership, the manager’s focus is on achieving departmental and organizational goals and in dealing fairly and equitably with employees. This is, in essence, the job of the manager. Making it a style allows the concentration of focus on behaviors that are directed toward goal achievement. When concern for employees’ well-being is added to this, it is a management combination that designates a person as a top manager and leader.5

Using this style allows the employee to determine the force, direction, and persistence of effort. A consistent Performance Leadership style, as perceived by the employee, will prevent employees from losing focus on the departmental or organizational goals and help them deal with uncertainty.6 Poor management and leadership styles leave employees feeling powerless,7 resulting in negative employee behaviors in the workplace that are seen by employees as the appropriate method of retaliation for bad management.8 This happens when managers and leaders see their subordinates as lazy and unwilling to contribute (Theory X managers/leaders).

McGregor9 identified two types of managers: those who believe in Theory X and those who believe in Theory Y. Theory X suggests that workers are lazy and unwilling to work, making the control and command system of management essential to management. Theory X managers try to constrain subordinate performance within the so-called bell curve; that is, a few need to be rated 1 and 5, a few more rated 2 and 4, but most should be rated as 3, for average performance. Of course, many do not know what actual ratings look like—they are ranking the employees, not rating or evaluating their performance.

This is a game that is played in many organizations by the top management team. To have an excellent organization, you must have excellent people. But excellent people may require raises, which the organization cannot afford. This is the catch-22 for managers, when the top management wants to play chicken management—using a poor evaluation as a reason not to give a raise. It is better to be honest with the evaluations, even if the raises across the board must be smaller.

McGregor suggested another theory, which he called Theory Y: People enjoy work and will be committed to meaningful work if treated well and rewarded with higher level rewards such as praise and recognition—not just money. Mary Parker Follett identified power with people as being much more effective than power over others.10 Having a strong focus on goals prevents the employee from thinking that the manager has power over her. Instead, a Performance Leadership style stresses that everyone is needed to make the organization work.

The Performance Leadership style uses the concepts developed in this book as a way to manage goals and employee accountability. When goals are set with the employees, it is possible to monitor their success and their constraints within the work environment. Employees also begin to understand the role that their tasks and duties play in achieving broader departmental and organizational goals. The emphasis in the Performance Leadership style is on employees as capable, competent (efficient and effective) adults with the ability to decide the amount of effort to provide, how to direct their efforts, and how long to provide the effort. Being able to understand and use Performance Leadership as a personal style and the Performance Leadership System as a management tool is a valuable and needed skill for all managers in every industry as well as every nonprofit organization. In the next chapters, the steps in using the Performance Leadership System to pursue Performance Leadership are discussed in detail, with exhibits and examples to demonstrate their use.

Why Use the Performance Leadership System?

Managing performance is the primary job of managers. It requires measurement.

Over the years of our work in industry and academia, managers and employees have said that they dread employee evaluations. In searching to find out why, we find that research and practice show that often managers and employees see the evaluation as a time for gotcha, where employees report that they feel that evaluation is simply a way to find their mistakes, not their successes.11 This is why gotcha management is used in this book as a phrase for a management style consisting of finding mistakes at the end of the year, without helping employees during the year to overcome them.

“Improving employee performance requires employees throughout the organization accepting responsibility for achieving organizational objectives, managers having complete confidence in their subordinates, information flowing effectively throughout the organization, and employees receiving honest task and performance feedback in short cycles.”12

One study13 found that only 3 out of 10 employees said that their evaluation helped improve their performance. Many employees believe that managers use it as an excuse not to give raises, even when they are deserved. Others find the process humiliating and embarrassing, particularly those being measured by a manager and a system that they consider illogical, inconsistent, contradictory, unscientific, or uncaring.14 Culbert15 reflects this feeling when he writes in the Wall Street Journal:

“. . . I see nothing constructive about an annual pay and performance review. It’s a mainstream practice that has baffled me for years. To my way of thinking, a one-side-accountable, boss- administered review is little more than a dysfunctional pretense. It’s a negative to corporate performance, an obstacle to straight-talk relationships, and a prime cause of low morale at work. Even the mere knowledge that such an event will take place damages daily communications and teamwork (author’s italics).”

However, managing performance means managing behaviors. Failure to deal with substandard performance or problem employees causes disruption, so dealing with the behaviors is essential. Otherwise, decreases in productivity and morale will occur, which will be reflected in the organization’s bottom line.16 On the other hand, failure to encourage high-performing employees can also cause drastic reductions in productivity and morale.

The solution is the simple, but effective, Performance Leadership System. Research shows that 86 percent of firms are not happy with their current performance management systems. Many, instead, are trying to avoid them or are focusing on software, measurement, and rating systems, which have not demonstrated any improvements in performance or productivity.17

The Performance Leadership System, correctly instituted, allows managers to manage and guide employees to benefit the organization. An effectively working Performance Leadership System benefits not only the organization but also the employees in the short and long term. It uses research developed by those working in performance management, where such benefits have been shown.18 The System requires ongoing analysis, design, identification, measurement, and alignment of tasks and duties to organizational and departmental strategic goals.19 An effective system outlines performance responsibilities, identifies employee contribution, engages employee motivation processes, and provides valid input to many decisions about employees, such as pay, promotion, and discipline.20 In some organizations, managers are given a different set of goals than the employees. This book is based on the belief that if everyone worked from the same goal set, negative perceptions of performance and hierarchy (us vs. them) could be avoided.

In this book, the process of managing performance using the Performance Leadership System is thoroughly described. This is not a textbook; instead, it is a practical book designed to make the Performance Leadership System readily available to managers. The best textbook on managing employee performance is Performance Management, by Herman Aguinis (2013), used in countless classrooms all over the world.

Performance Leadership is an interesting topic, but there are a lot of issues surrounding it that get missed in day-to-day leadership and management work. The entire system is covered in this book from beginning to end, but the only way to successfully manage performance is to use the entire system—not just parts of it. There are many areas where the Performance Leadership System can correct critical problems. Even the Baldrige Performance Excellence Program21 has several sections on employee performance management requirements conforming to this System.

However, most performance management systems are incorrectly designed. Quick fixes and fads are numerous in popular management literature and support countless consulting firms. Employee evaluations have been used solely for personnel decisions instead of its true purpose: assessment and modification of the direction of employee and management effort.22 Organizations do not usually reward the use of this information by managers, but it seems an easy way for goal-oriented managers to gain performance improvements quickly by using them as goal achievement measures. The improved performance and productivity will be an important part of managers’ evaluations!

This book does not discuss fashions and fads in appraisal/evaluation that come and go. Instead, we focus on the process of creating and sustaining the Performance Leadership System that leads to improved performance and a Performance Leadership style. The entire System is explained in language that is free of jargon, giving step-by-step processes. Skipping steps in the Performance Leadership System will neither benefit the manager nor the employees.19 Instead, it will set up unfulfilled expectations that create distrust.

Effective systems can prevent discontent, turnover, neglect of the job, apathy, and lawsuits because the processes and distributions are transparent.20 Our performance management system is designed to be:

“. . . associated with an approach to creating a shared vision of the purpose and aims of the organization, helping each employee understand and recognize their part in contributing to them, and in so doing, manage and enhance the performance of both individuals and the organization.”23

Why Bother with Analyzing and Measuring Job Performance?

The primary job of any manager is to manage performance to be sure that organizational, departmental, and/or subdivisional goals are met. Many managers say that they do not receive good performance from their employees.

The focus of leadership and management is achieving goals through working with other people. If goals are not being achieved, then employee performance must clearly be modified toward current, needed goal achievement instead of outdated, irrelevant goals.25 If performance is not at the level needed, then expectations should be raised and clearly identified.

Amazing things have been done when expectations were raised—not raised to unreasonable or unfair expectations, but to achievable ones. Often, failure in goal achievement is not the fault of the employee but of the manager, when she fails to provide mentoring and coaching and is unclear about goals, outcome expectations, resource availability, environmental constraints, timeliness, and consequences. These issues are discussed throughout the book.

Coaching and mentoring are two different processes. The British Chartered Institute Personnel and Development24 provides one of the clearest definitions of the differences between the two. Coaching involves a focus on employee skill development and goal achievement, usually for a short time or as part of a management style. Mentoring is more involved, having social as well as organizational effects. The mentor shares the knowledge of the organization and its workings with the protégé. Often, the protégé’s progression through the organization is the major focus of the mentoring relationship. Managers rarely make good mentors for their subordinates; the nature of the relationship is different.

Managers should coach rather than judge when implementing the Performance Leadership System. This requires managers to shift their supervisory role from judge to coach. Employees feel supported by managers and more secure in their positions when they know that managers are more focused on improving and developing the performance of employees than in judging and criticizing. However, this is achieved only when supported by an organizational culture/work environment that encourages self-management.

If performance is not measured and assessed, it is not possible to determine whether goals are even met. Goals can be extremely powerful, when the goals are clear. This has become very clear in the area of terrorism; with powerful goals, things thought impossible can be achieved, such as the use of four large jetliners to create havoc in the United States. (Goal setting is discussed in Chapter 5.)

Peter Drucker, one of the leaders in the management field in the 1900s, believed that measuring performance is important:

“Work implies not only that somebody is supposed to do the job, but also accountability, a deadline and, finally, the measurement of results—that is, feedback from results on the work and on the planning process itself.”25

Drucker also said, “Your first [management] role . . . is the personal one,” Drucker told Bob Buford, a consulting client then running a cable TV business in 1990. “It is the relationship with people, the development of mutual confidence, the identification of people, the creation of a community. This is something only you can do.” Drucker went on, “It cannot be measured or easily defined. But it is not only a key function. It is one [function] only you can perform.”26

A major part of Performance Leadership is goal setting and measuring progress toward those goals, discussed in Chapters 5 and 6. The Performance Leadership System allows managers to set performance goals with their subordinates, measure progress and performance, create strategies for improvements, and provide feedback. When most people talk about performance management, employee evaluation/assessment, or worker assessment, they really mean the measurement of performance. This is a fundamental part of Performance Leadership, but it comes only after creating an entire system.19

The use of the term performance appraisal refers to the process of measuring performance to help in the Performance Leadership System. It is not an entire system on its own. Performance appraisals are usually viewed as punitive, with a lot of negative connotations based on past treatment or perceived unfairness in the workplace and its culture.27 Performance appraisals can be destructive if the performance appraisal system does not have objective criteria and fair procedures.27 “To overcome the potential destructive effects of performance appraisals, the organization should implement fair appraisal procedures that contain objective and measureable performance criteria.”28

Managers dread telling employees that their work is substandard or that improvement is needed. They really just want to get it over with. Often they are concerned that the employee will take the criticism poorly. And employees are likely to react badly to criticism when they view the criticism as subjective and destructive, feel that their performance is poorly measured, or receive feedback unrelated to the reality that they face in the workplace—such as a lack of resources to do the job well. Some managers enjoy the yearly evaluation process for a negative reason: they see it as an opportunity to “jerk the employees up a notch,” which they consider motivating. This attitude is in reality poor (gotcha or chicken) management.

Are Performance Appraisals Needed in the 21st-Century Workplace?

Yes, they continue to be critical to organizational and departmental goal achievement and overall success. Some people want to abolish performance appraisals altogether.29 Eliminating the management style that uses performance appraisals without a performance system, such as the Performance Leadership System, is advised!

But effective and efficient management and leadership requires use of the Performance Leadership System, including measurement.25 Edward Deming, the major designer of quality improvement, strongly believed that performance appraisal, when done poorly, is demotivating, leaving people “unfit for weeks after receipt of rating, unable to comprehend why they are inferior.”30 In fact, Culbert31 heavily criticized performance appraisals in the Wall Street Journal Online:

“This corporate sham is one of the most insidious, most damaging, and yet most ubiquitous of corporate activities. Everybody does it, and almost everyone who’s evaluated hates it. It’s a pretentious, bogus practice that produces absolutely nothing that any thinking executive should call a corporate plus.”

Happy workers are not always productive workers. However, productive workers performing well in jobs that have meaning are generally content and satisfied with the organization and the work, which results in better retention of valued employees.32 Productive workers are clear about their purpose within the organization and how their own goals parallel those of the organizations and departments where they work.33

The key is in understanding each employee’s motivation to come to work and aligning those goals with departmental and organizational goals.34 It also requires that working conditions and pay be incentives, not disincentives, as described by Hertzberg,35 and since then by many other researchers. When working conditions are poor and interfere with job performance and when pay is below the norm for the job (as judged by the employee, not the manager), they create reasons for employees to be unsatisfied with their job, which reduces employee motivation.

All managers want employees that are highly motivated, engaged, and productive. But this is challenging, because motivation is an internal process, influenced by many things over which the manager has no control. Money doesn’t motivate everyone. It is a particularly poor motivator for those who are committed, paid appropriately (in their judgment), and high-performing employees already. In some industries, including healthcare and academia, financial rewards are extremely limited. Also, employee performance, especially at higher levels, such as manager, project manager, and top management team, is difficult to observe. Monetary incentives are the baseline, but there are many factors affecting an employee’s motivation level, reflective of their personalities and personal expectations. Mo Amani, one of our reviewers, suggested that if a person is unwilling to be interested or if the person does not fit well into the organization, they are unlikely to motivate themselves to achieve goals.

A further negative component of many workplace performance appraisals is the assumption that higher level employees do not need supervision in the same manner as lower level employees. There might also be the perception that lower level employees are totally motivated by money and must be watched constantly to ensure their performance. This view of workers is held by managers who believe in the Theory X management style, which has been found to be detrimental to high performance.9 It should also be noted that feelings about evaluation are affected by how we have been evaluated and treated since entering the workforce—even since childhood. However, evaluations should be based on (1) facts, (2) data that are collected in a specified manner over a specified time, and (3) specified measurement systems, as demonstrated in the Performance Leadership System.

But How Do We Get Appropriate Measurement?

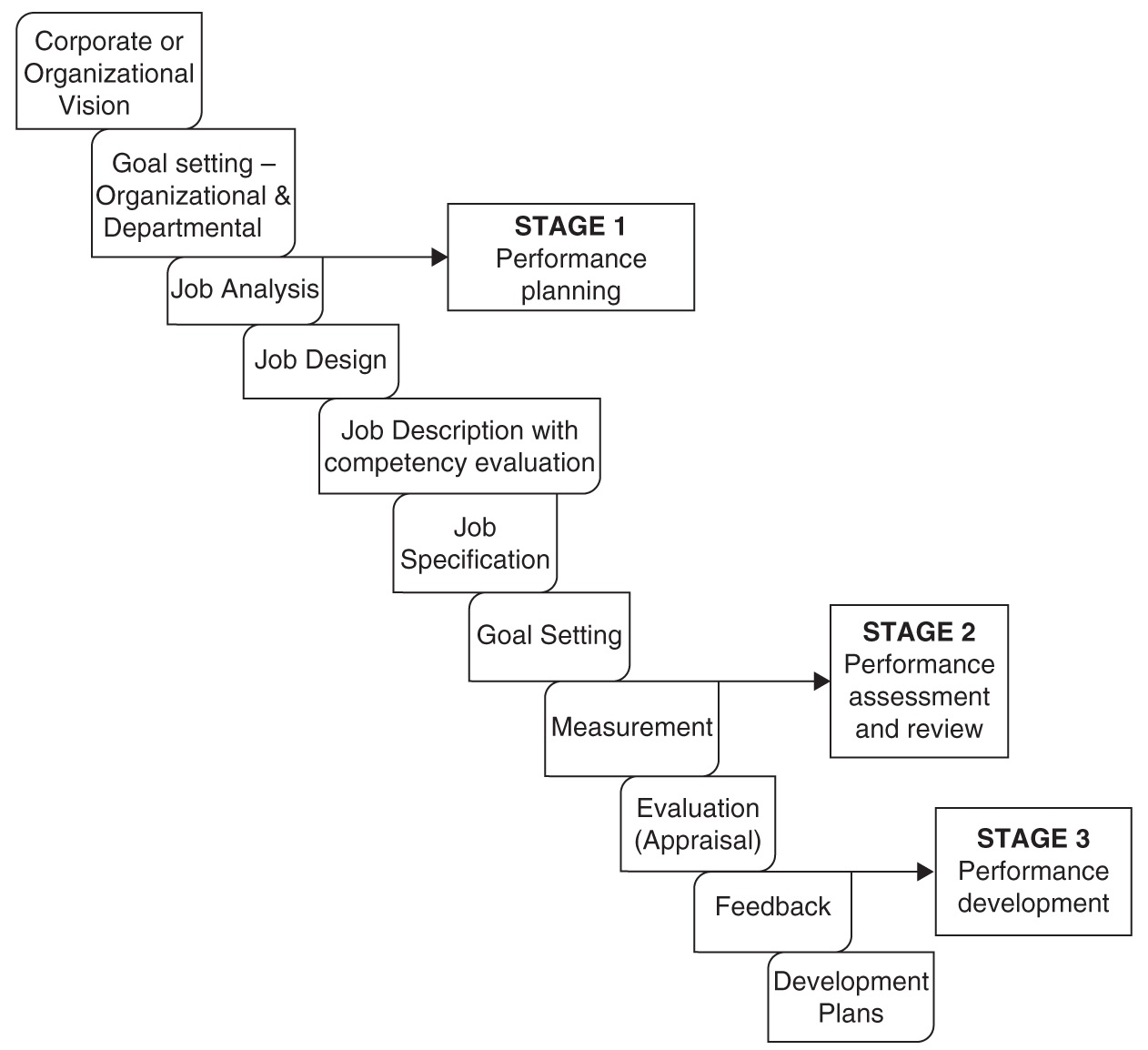

How do we know what the employees are supposed to be doing and whether they are doing it correctly? The only way to obtain appropriate measurements of performance is to create a reliable, valid, and respected performance measurement system, as shown in Exhibit 1.1. One of the best definitions of reliability and validity is given on the University of Southern Florida website36:

“Validity refers to the accuracy of the assessment—whether or not it measures what it is supposed to measure. Even if a test is reliable (consistent), it might not provide a valid measure.”

An example might be a bathroom scale that registers your weight at 150 pounds every time you step on it, even though you know that your weight is 130 pounds. The scale is reliable (consistent), but it is not valid. A respected system is one that is highly esteemed by those using it and affected by it.37

As you can see, the system doesn’t start with job analysis, but with vision, mission, and goal setting at the organizational and then departmental level. Before job analysis can begin, the manager must be sure that the vision and mission of the organization are clear to him and to his employees. Goals are set from the vision and mission of the organization, and the department then sets goals based on the organizational goals. Without this step, the rest will not work as well.

Following the vision, mission, and goal setting is job analysis.19 Job analysis allows both the manager and employee to understand the elements of the job. Notice that it is both manager and employee who must understand the job elements. The next step in the system involves job design. The third step is creating an appropriate job description followed by a job specification. Using the Performance Leadership System requires that both the manager and employee who performs the job work together to create the tools for measurement. Only then are we ready to create the performance evaluation or appraisal tool and set goals. The last step is feedback, which includes development planning.19

Exhibit 1.1 illustrates the steps in the system and how they fit together to create a Performance Leadership System. Failure to complete one of these steps before proceeding to the next will result in failure of the entire system. The parts do not work in isolation; similar to a car: all parts are necessary for the Performance Leadership System to operate effectively and efficiently.

Exhibit 1.1 Steps in the Effective Performance Leadership System

Organizations are usually concerned with having the appropriate processes in place and sometimes they even train managers, but the outcomes, unintended consequences, and signals from an employee perspective are rarely examined.14 In this book, the employee perspective is considered, as are the managerial and organizational perspectives, illustrated in Exhibit 1.2. Feedback is essential to understand the results and signals37 because planned implementation of any system may not yield expected outcomes.38

Exhibit 1.2 Outcomes of Human Resource Management Practices

Source: Adapted from Nishii & Wright, 2008.

Perception causes attitudes and behaviors and their outcomes or, in our case, employee performance.39 If employees perceive the process of employee performance assessment and outcome decisions to be fair, they often reciprocate with positive outcomes, including organizational commitment.40

Organizational commitment or belongingness, as Maslow41 termed it, creates an employee focus on organizational and personal goal alignment, leading them to invest time and effort in their jobs.42 It also helps employees increase their performance and assist in other unrequired work, as responses to belongingness.43

This is where a win–win strategy becomes beneficial for both organizations and employees. Mary Parker Follet, the renowned management expert, explained that win–win is more than compromise, it is cooperation and collaboration. When people are engaged in a joint effort, the management and leadership become more powerful using power with rather than power over.10

So Where Is the Proof that a Complete System of Performance Leadership Works?

Appropriate Performance Leadership systems (under the name of performance management) have been shown to be a useful tool for managers through both research and practice.44 The systems, when properly and totally employed, allow managers to:

• Manage employee performance,

• Develop employee skills, and

• Create a sustainable competitive advantage.

Appropriate use of these systems increases attraction and retention of human resources (tangible assets) and their knowledge (intangible assets) to the firm, as well as reducing rates of turnover.45 It provides cost savings and increased profits through performance and productivity improvements.44

Martinez,46 in her case study of an electric company, cites increased manager and employee focus on company goals as the #1 benefit from using such a system. She stated that the firm was able to align operational and strategic objectives. As with the Performance Leadership System, all employee tasks are openly focused on the firm’s goals. In this case study, the author reports that, as a side benefit, the firm’s reputation was also improved. Other benefits Martinez found include business improvement, increased customer satisfaction, and increased employee satisfaction. Other research results also found benefit in the discussions about goals and objectives between managers and employees, and a focus on resources needed to complete tasks effectively and efficiently.47

Research as well as practical experience is used in this book to demonstrate how the Performance Leadership System works and to discuss the positive outcomes achieved using the system. But the bottom line for managers is that few, if any, of the fad performance appraisal systems have worked in isolation, and there is definite support from research and practical experience to show that this one does. The Performance Leadership System presented in this book works only when all of the steps are used in the correct sequence: You cannot pick and choose the parts of the system that you want to use—you must use it all, from start to finish. It takes time to use the Performance Leadership System, particularly when first starting to implement it. However, the benefits are enormous and create a culture that emphasizes:

• Lessening the time spent on performance issues, after implementation,

• Increased productivity, and

• Increased satisfaction of both the manager and the employee.

The system works for any level in the organization, including the general manager or chief executive officer in a profit or nonprofit organization. In fact, one of the reasons for chief executive officer failures is that there is rarely an understanding of the job duties and outcomes by those who oversee that position (such as a board of directors, stockholders, or other stakeholders of the organization). Therefore, monitoring chief executive and other officer performance becomes increasingly difficult, resulting in such things as the banking collapse, the automobile industry collapse, and ethical problems as with Enron.

In the final chapter, the issue of organizational culture is outlined. Culture determines “the way that we do things around here,” and leaders are responsible for the culture of the organization and/or department. Culture is not thoroughly discussed in this book, but we recommend Cameron’s and Schein’s work in the area.48

Example 1.1

Christina walked in the door and went straight to her desk, finding three receiving documents piled one on top of another. “What is this?” she asked Jose.

“You were late again,” he said. “I had to do the receiving, as usual. Aren’t you supposed to be here at 8? Why are you always late?”

“It’s only 8:15,” Christina replied. “And what’s the big deal anyway. I always work over when I’m late. I don’t think you should be making such a big deal out of it.”

Mark heard the conversation from his office, went into the warehouse, and suggested that they both get back to work. Christina’s lateness had come to the attention of his boss through gossip; clearly Mark had to do something. Jose and Christina were two of the best workers that he had ever seen, but Christina’s continual late arrivals meant that Mark wasn’t seen as an effective manager by his boss or subordinates.

What Is the Problem Here? How Can Performance Leadership Help in this Situation?

Clearly, the problem had not been dealt with appropriately. Had Christina been asked to change her pattern of behavior early, it might not have become an issue. As it was, it had been brought to the attention of Mark’s boss, making him look ineffective to everyone. The Performance Leadership System ensures that:

1. The requirements for arriving to work on time would have been linked to the organizational and departmental goals.

2. Late arrivals would have been marked and the employee counseled on the first and second occurrences for feedback and development plans. Reasons, root causes, and resolutions should be discussed.

3. Appropriate measures would have been taken with the third and subsequent occurrences.

Offers to assist in the underlying problem would have been offered, if the underlying cause can be assessed. In some cases, this might be the Employee Assistance Program. In this particular case, it might be someone offering to purchase an alarm clock. In some cases, the employee might not wish to share the underlying cause; therefore, it is up to the employee to solve the problem alone or suffer appropriate consequences.

It may be a personal issue, such as dropping a child off at day care or school and trying to rush to work. The employee and the manager can work together to find an answer, such as finding a day care closer to work or one that opens earlier. The manager might officially change her hours of work, making Christina’s arrival 15 or 30 minutes later than it is now. With thought, multiple alternatives can be generated and an appropriate solution found, based on the root cause and feedback.

Notes

1. We did not use real names or incidents here. These are experiences that we have had or stories that our students, colleagues, and clients tell us. They are primarily meant as an introduction to the topic to be discussed.

2. Whetten & Cameron, 2016.

3. Spriggs & Barnes, 2015.

4. Conger & Kanungo, 1988.

5. Antonakis & House, 2002; Judge, Piccolo, & Ilies, 2004; Keller, 2006.

6. Cropanzano & Wright, 2001.

7. Bennett, 1998; Martinko, Gundlach, & Douglas, 2002.

8. Thau, Bennett, Mitchell, & Mars, 2009.

9. McGregor, 1960.

10. Mele, 2006.

11. Markle, 2000.

12. Likert, 1961, elaborated upon in Hauenstein, 2011.

13. Holland, 2006.

14. Farndale & Kelliher, 2013.

15. Culbert, 2008.

16. Flynn & Stratton, 1981.

17. Rock, Davis, & Jones, 2013.

18. Gardner, Moynihan, Park, & Wright, 2001.

19. Aguinis, 2013.

20. Clausen, Jones, & Rich, 2008.

21. Baldrige Performance Excellence Program (http://www.baldrigepe.org/; http://asq.org/learn-about-quality/malcolm-baldrige-award/overview/overview.html; http://www.nist.gov).

22. Moynihan & Pandey, 2010.

23. Fletcher, 1993, quoted by Ahmed & Kaushik, 2011, p. 102.

24. http://www.cipd.co.uk/hr-resources/factsheets/coaching-mentoring.aspx

25. Drucker, 1993.

26. http://www.druckerinstitute.com/2013/07/measurement-myopia/

27. Coens & Jenkins, 2002.

28. Simsek et al. 2012, p. 49.

29. See for example: Coens & Jenkins, 2002; Markle, 2000.

30. Deming, 2000, p. 102.

31. Culbert, 2010.

32. Hansen & Keltner, 2012; Steelman & Rutkowski, 2004; Wrzesniewski, LoBuglio, Dutton, & Berg, 2013.

33. See, for example, Cropanzano & Wright, 2001; Taris & Schreurs, 2009; Wrzesniewski, LoBuglio, Dutton, & Berg, 2013.

34. Jemielniak, 2014; Morse & Weiss, 1955; Ross, Schwartz, & Surkiss, 1999.

35. Herzberg in his book (1966) and article (2003).

36. University of Southern Florida (http://fcit.usf.edu/assessment/basic/basicc.html).

37. Haggerty & Wright, 2009.

38. Barney, 2001; Nishii & Wright, 2008; Wright, Gardner, Moynihan, & Allen, 2005.

39. Erdogan, 2002.

40. Blau, 1964; Eisenberger, Huntington, Hutchison, & Sowa, 1986; Masterson, Lewis, Goldman, & Taylor, 2000; Robinson, Kraatz, & Rousseau, 1994; Whitener, 2001.

41. Maslow, 1943, 1954.

42. Cohen, 1992; Fedor, Caldwell, & Herold, 2006; Lease, 1998; Mathieu & Zajac, 1990; Mowday, Steers, & Porter, 1979.

43. Blau, 1964; Guest, 1987; Organ, 1990.

44. See for example, Lussier & Hendon, 2013.

45. Allen, Bryant, & Vardaman, 2010; Daniel, 2014.

46. Martinez, 2005.

47. See for example, Ukko, Tenhunen, & Rantanen, 2007.

48. See for example, Cameron & Quinn, 2011; Schein, 2014.