Role of Culture in Cross-Border Negotiations

Credibility is essential in cross-cultural negotiations

—Anonymous

In a globalizing world, companies operate in a multicultural environment. Even when people from other nations may seem to present a similar perspective, they are different in many ways, defined by their cultures. Even if they speak English, they view the world differently. They define business goals, express thoughts and feelings, and show interest in different ways. Culture is a deep-rooted aspect of a person’s life that is always present. No manager can avoid bringing his or her cultural assumptions, images, prejudices, and other behavioral traits into a negotiating situation.

Culture includes all learned behavior and values that are transmitted through shared experience to an individual living within a society. The concept of culture is broad and extremely complex. It involves virtually every part of a person’s life and touches on virtually all human needs, both physical and psychological. A classic definition is provided by Sir Edward Taylor: “Culture is that complex whole which includes knowledge, belief, art, morals, law, custom, and any other capabilities and habits acquired by individuals as members of society.”1

Culture, then, develops through recurrent social relationships that form patterns that are eventually internalized by members of the entire group. It is commonly agreed that a culture must have these three characteristics2:

It is learned; that is, people over time transmit the culture of their group from generation to generation.

It is interrelated; that is, one part of the culture is deeply connected with another part, such as religion with marriage or business with social status.

It is shared; that is, the tenets of the culture are accepted by most members of the group.

Another characteristic of culture is that it continues to evolve through constant embellishment and adaptation, partly in response to environmental needs and partly through the influence of outside forces. In other words, a culture does not stand still, but slowly, over time, changes.

Effect of Culture on Negotiation

Culture is non-negotiable. Deal or no deal, people do not change their culture for the sake of business. Therefore, it behooves negotiators to accept the fact that cultural differences exist between them and try to understand these differences. Cultural differences can influence business negotiations in significant and unexpected ways. Summarized below are the major effects of culture on cross-border negotiations.3

Definition of Negotiation

The basic concept of negotiation is interpreted differently from one culture to another. In the United States, negotiation is a mechanical exercise of offers and counteroffers that leads to a deal. It is a cut-and-dry method of arriving at an agreement. In Japan, on the other hand, negotiation is sharing information and developing a relationship that may lead to a deal.

Selection of Negotiators

The criteria for the selection of negotiators vary from culture to culture. Usually, the criteria include knowledge of the subject matter, seniority, family connections, gender, age, experience, and status. Different cultures assign different importance to these criteria in choosing of negotiators. In the Middle East, for example, age, family connection, gender, and status count more; while in the United States, knowledge of the subject matter, experience, and status are given more weight.

Protocol

The degree of formality used by the parties in the negotiation is affected by their cultures. Culturally, the United States is an informal society, such that Americans like to address other people by their first name upon first meeting. Europeans, on the other hand, are highly title conscious. While in the United States, graduate students call their professor by his or her first name, in Germany, a professor with a Ph.D. has to be addressed as Professor or Doctor.

Presentation of business cards at the beginning of a first meeting is normal protocol in Southeast Asia. As a matter of fact, the cards must be presented in a proper manner. In the United States, cards may or may not be exchanged and there is no cultural norm of presenting the cards. In many traditional cultures, a man placing the other person’s business card in his wallet and then putting the wallet in his back pocket is considered an insult. (Women negotiators do not have this problem.) Likewise, methods of greeting as well as dress codes are impacted by one’s culture. The way a person greets the other party or dresses for the occasion communicates his or her interest and intentions relative to the negotiation.

Communication

As noted in Chapter 1, culture plays a significant role in how people communicate, both verbally and nonverbally. Language as a part of culture consists not only of the spoken word, but also of symbolic communication of time, space, things, friendship, and agreements. Nonverbal communication occurs through gestures, expressions, and other body movements.

The many different languages of the world do not translate literally from one to another, and understanding the symbolic and physical aspects of communication in different cultures is even more difficult to achieve. For example, the phrase body by Fisher translated literally into Flemish means “corpse by Fisher.” Similarly, Let Hertz put you in the driver’s seat translated literally into Spanish means “Let Hertz make you a chauffeur.” Nova translates into Spanish as “it doesn’t go.” A shipment of Chinese shoes destined for Egypt created a problem because the design on the soles of the shoes spelled God in Arabic. Olympia’s Roto photocopier did not sell well because roto refers to the lowest class in Chile, and roto in Spanish means “broken.”4

In addition, meanings differ within the same language used in different places. The English language differs so much from one English-speaking country to another that sometimes the same word means something entirely different in another culture. Table the report in the United States means “postponement” while in England, it means “bring the matter to the forefront.”

A case of nonverbal communication is body language. A certain type of body language in one nation may be innocuous, while in another culture, the same body language may be insulting. Consider the following examples.

Never touch a Malay on the top of the head, for that is where the soul resides. Never show the sole of your shoe to an Arab, for it is dirty and represents the bottom of the body, and never use your left hand in Muslim culture, for it is the hand reserved for physical hygiene. Touch the side of your nose in Italy, and it is a sign of distrust. Always look directly and intently into your French associate’s eye when making an important point. Direct eye contact in Southeast Asia, however, should be avoided until the relationship is firmly established. If your Japanese associate has just sucked air in deeply through his teeth, that’s a sign you’ve got real problems. Your Mexican associate will want to embrace you at the end of a long and successful negotiation; so will your Central and East European associates, who may give you a bear hug and kiss you three times on alternating cheeks. Americans often stand farther apart than their Latin associates but closer than their Asian associates. In the United States, people shake hands forcefully and enduringly; in Europe, a handshake is usually quick and to the point; in Asia, it is often rather limp. Laughter and giggling in the West indicates humor; in Asia, it more often indicates embarrassment and humility. Additionally, the public expression of deep emotion is considered ill-mannered in most countries of the Pacific Rim; there is an extreme separation between one’s personal and public selves. The withholding of emotion in Latin America, however, is often cause for mistrust.5

The meaning and importance of time vary from culture to culture. In Eastern cultures, time is fluid and circular; it goes on forever. Therefore, if delay occurs in negotiation, it does not matter. In the United States, time is fixed and valuable. Time is money, which should not be wasted. For this reason, North Americans like to begin negotiation on time, schedule discussions from hour to hour to complete the day’s agenda, and meet the deadline to close the negotiation. To a Chinese, however, the important thing is to complete the task, no matter how long it takes.

Risk Propensity

Cultures differ in their willingness to take risks. In cultures where risk propensity is high, negotiators are able to close a deal even if certain information is lacking but the business opportunity otherwise looks attractive. Risk-prone cultures suggest caution. Negotiators belonging to risk-averse cultures demand additional information to carefully examine all sides of a deal before coming to a final agreement.

Groups Versus Individuals

In some cultures, individuality is highly valued. In others, the emphasis is on the group. In group-oriented cultures, negotiation takes more time to complete since group consensus must be built. For example, in a negotiation in China, a U.S. negotiator had to meet six different negotiators and interpreters, going over the same material until the deal was completed. Compare that to the United States, where individuals can make decisions without getting approval from the group.

Nature of Agreement

The nature of agreement also varies from culture to culture. In the United States, emphasis is placed on logic, formality, and legality of the agreement. For example, when a deal can be completed at a low cost, when all details of the agreement are fully spelled out, and when the agreement can be enforced in a court of law, it is satisfactory. In traditional cultures, a deal is struck depending on the family or political connections, even when certain aspects of the agreement are weak. Furthermore, an agreement is not permanent and is subject to change as circumstances evolve.

Understanding Culture

The first step in gaining cultural understanding is to identify the group or community whose culture you want to know more about. Culturally, the world can be divided into a large number of groups, with each group having its own traditions, traits, values, beliefs, and rituals. People often speak in generalities, such as Asian culture, Latin culture, Western culture, and so on. With regard to negotiations, having a broad perspective about Asians is not sufficient since a Japanese negotiator may hold different values than a Chinese or a Korean. Similarly, a culture and a nationality are not always the same. In India, for example, Southern Indians may represent a different culture than Northern Indians. Indian Muslims are a different cultural group from Hindus. That is, a country may have several distinct cultural groups.

Once a negotiator knows the cultural group to which the other party belongs, he or she should attempt to understand the history, values, and beliefs of the culture. The best way to learn the culture of another group is to devote many years to studying the history, mastering the language, and experiencing the way of life by living among the people. For a prospective negotiator, however, this commitment is inconceivable. As an alternative, therefore, you should gain as much insight into the culture of the group as possible by reading books, talking to people who are knowledgeable about the group, and hiring consultants who specialize in conducting business deals with the group.

As you undertake to understand the culture of the group, you may wonder what particular aspects you should concentrate on. This is important since culture per se is a broad field, and you may not learn much even after reading many books if you do not know what you are trying to achieve.6 For negotiators, the relevant cultural knowledge can be divided into two categories: (1) traditions and etiquette, and behavior of the group (which can be further split into protocols and deportment, and deeper cultural characteristics), and (2) players and the process.

Before elaborating further on these categories, understand that cultural knowledge should be used with caution. You should avoid forming stereotypical notions about a group and considering them as universal truths. For example, not all Japanese avoid giving a direct negative answer. Not all Mexicans mind discussing business over lunch. Not all Germans make cut-and-dry comments about proposals. As a matter of fact, people are offended when you use stereotypes to describe their culture. A Latin executive would be offended if you said to him, “Although we plan to start the meeting at 9 a.m., I know you won’t be here before 9:30 since Latinos are always late.”

In addition to national cultures, negotiators need to be aware of professional and corporate cultures. Professional cultures refer to individuals who have studied a specific discipline, such as accounting, economics, engineering, and chemistry. As a result of their studies, these professionals have developed analytical skills, have acquired technical jargon, and tend to look at problems through their own professional interest (which sets them apart from their typical national culture).

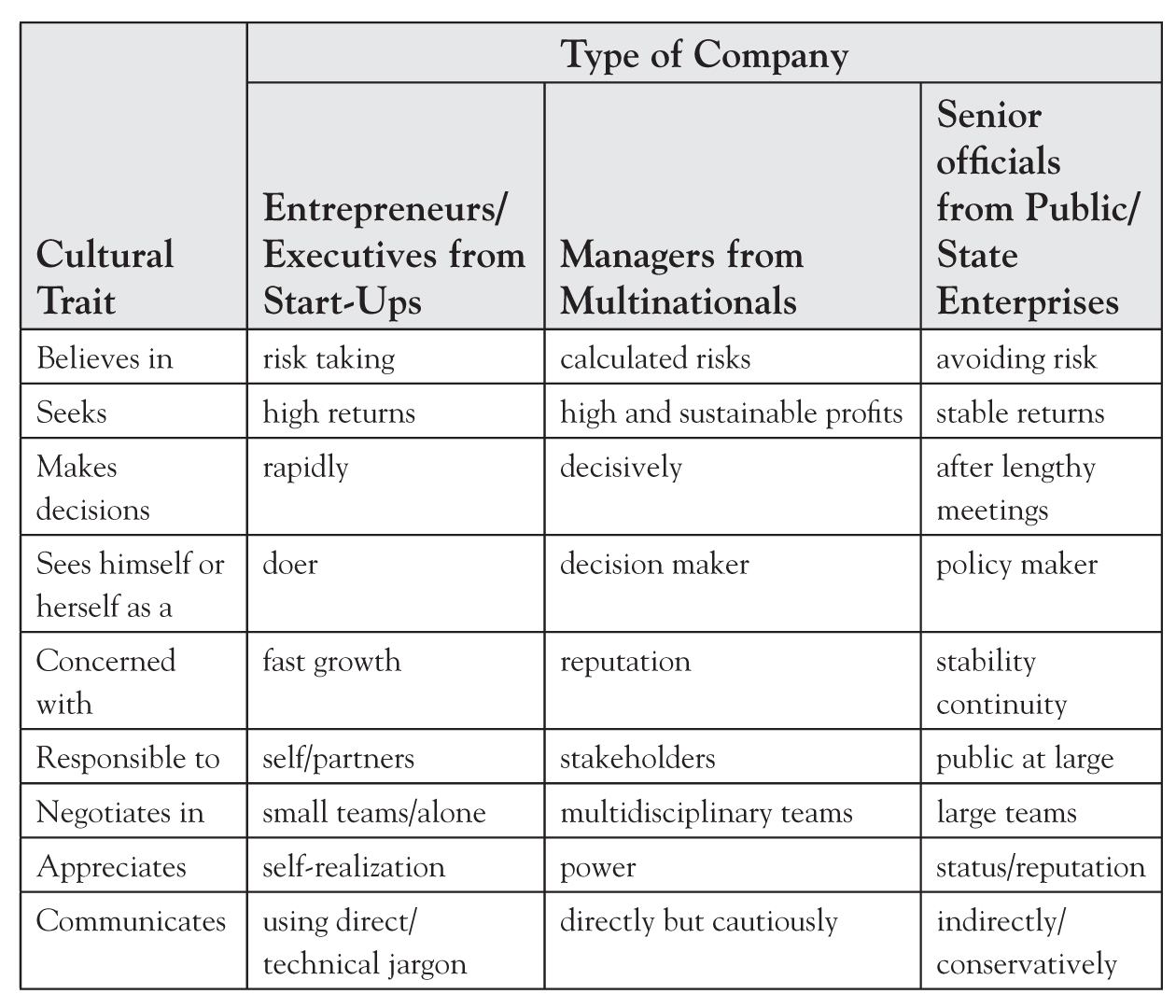

Corporate cultures play a significant role in business negotiations. All companies over the years develop their own business culture, values, rules, and regulations. For example, an official from a state-owned enterprise or from a public utility has a different style than a manager from a high-tech start-up. An entrepreneur is likely to have a negotiating style different from that of a CEO of a multinational (see Figure 2.1).

Figure 2.1 Cultural differences among managers belonging to different types of companies

Experience shows that these cultural traits are only indicative and must be dealt with cautiously in view of two other factors that influence the behavior of negotiators. One is age, and the other is multiculturalism. Today, young professionals have more affinity among themselves. It is not uncommon to meet young executives who have studied abroad, who speak one or more foreign languages, and who have traveled extensively. These executives feel comfortable working outside their cultural environment and are no longer representatives of their own culture.

Similarly, executives with overseas experience have, over the years, developed greater understanding of foreign cultures while acquiring new values and tolerance for cultural diversity. Such executives are more multicultural oriented. For these reasons, the wise negotiator finds out as much as possible about the background of the other party to avoid committing cultural blunders that can derail the discussions as well as lead to inferior outcomes.

Protocol and Deportment

Hundreds of articles, and numerous books and manuals have been written about cultural traits of different groups, advising global businesspeople what to do or not to do in different matters. Consider the following cross-cultural negotiating behavior ascribed to different societies:

• English negotiators are very formal and polite and place great importance on proper protocol. They are also concerned with proper etiquette.

• The French expect others to behave as they do when conducting business. This includes speaking the French language.

• Protocol is important and formal in Germany. Dress is conservative; correct posture and manners are required. Seriousness of purpose goes hand in hand with serious dress.

• The Swedes tend to be formal in their relationships; dislike haggling over price; expect thorough, professional proposals without flaws; and are attracted to quality.

• Italians tend to be extremely hospitable but are often volatile in temperament. When they make a point, they do so with considerable gesticulation and emotional expression.

• The Japanese often want to spend days or even weeks creating a friendly, trusting atmosphere before discussing business.

• In China, the protocol followed during the negotiation process should include giving small, inexpensive presents. As the Chinese do not like to be touched, a short bow and a brief handshake are used during the introductions.

• Business is conducted in a formal yet relaxed manner in India. Having connections is important and one should request permission before smoking, entering, or sitting.

• Emotion and drama carry more weight than logic does for Mexicans. Mexican negotiators are often selected for their skill at rhetoric and for their ability to make distinguished performances.

• For Brazilians, the negotiating process is often valued more than the end result. Discussions tend to be lively, heated, inviting, eloquent, and witty. Brazilians enjoy lavish hospitality to establish a comfortable social climate.

• Russian executives tend to distrust executives who are consumed with business issues only. They are extremely cautious when dealing with parties for the first time.

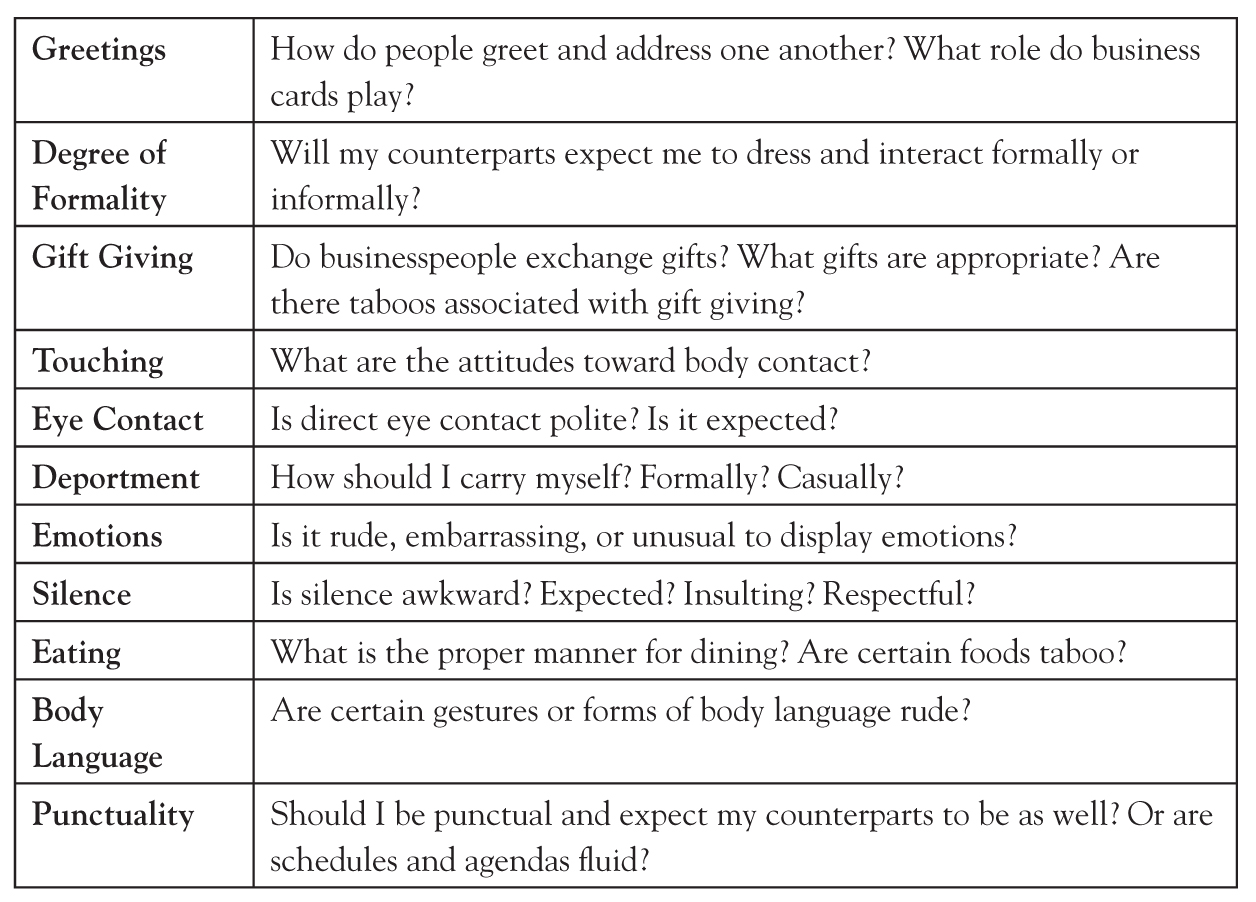

Such a list—about the cultural differences between different groups—can go on and on. While such information might help a negotiator avoid certain mistakes, it is too general to be useful in negotiations. Further, while culture does have a role in negotiation, other factors, such as personality of the negotiator and the culture of the organization to which the negotiator belongs influence negotiation behavior. As a guide, therefore, a negotiator should seek answers to the questions about protocol and deportment shown in Figure 2.2. Sensitivity to these issues allows a negotiator to avoid being offensive, to demonstrate respect, to enhance cordial relationship, and to strengthen communication.

Figure 2.2 Cross-cultural etiquette

Source: James K. Sebenius, “The Hidden Challenge of Cross-Border Negotiations,” Harvard Business Review, March 2002, pp. 80.

Deeper Cultural Characteristics

Two frameworks are presented for gaining deeper behavior knowledge of a culture: Hall’s “Silent Language” and Hofstede’s Cultural Dimensions.

Hall’s Framework

According to Hall, the following aspects drive surface behavior, and their understanding can be of immense help in seeking cultural knowledge of a group.7

• Relationship: Is the culture deal-focused or relationship-focused? In deal-focused cultures, relationships grow out of deals; in relationship-focused cultures, deals arise from already developed relationships.

• Communication: Are communications indirect and “high-context” or direct and “low-context”? Do contextual, nonverbal cues play a significant role in negotiations, or is there little reliance on contextual cues (see Figure 2.3). Do communications require detailed or concise information? Many North Americans prize concise, to-the-point communications. Many Chinese, by contrast, seem to have an insatiable appetite for detailed data.

Figure 2.3 Low-context versus high-context communication

Source: Excerpted from Donald W. Hendon, Rebecca A. Hendon, and Paul Herbig, Cross-Cultural Business Negotiations (Westport, CT: Quorum Books, 1996), pp. 65–67.

• Time: Is the culture generally considered to be “monochronic” or “polychronic”? In Anglo-Saxon cultures, punctuality and schedules are often strictly considered. This monochronic orientation contrasts with a polychronic attitude, in which time is more fluid, deadlines are more flexible, interruptions are common, and interpersonal relationships take precedence over schedules. For example, in contrast to the Western preference for efficient deal making, Chinese managers are usually less concerned with time.

• Space: Do people prefer a lot of personal space, or are they comfortable with less? In many formal cultures, moving too close to a person can produce extreme discomfort. By contrast, a Swiss negotiator who instinctively backs away from his up-close Brazilian counterpart may inadvertently convey disdain.

Hofstede’s Cultural Dimensions

According to Hofstede, the way people in different countries perceive and interpret their world varies along four dimensions: power distance, uncertainty avoidance, individualism versus collectivism, and masculinity. Hofstede drew his conclusions based on his interviews with 60,000 employees of IBM in over 40 countries.8

Power Distance (Distribution of Power): Power distance refers to the degree of inequality among people the population of a country considers acceptable (i.e., from relatively equal to extremely unequal). In some societies, power is concentrated among a few people at the top who make all the decisions. People at the other end simply carry out these decisions. Such societies are associated with high power distance levels. In other societies, power is widely dispersed and relations among people are more egalitarian. These are low power distance cultures. The lower the power distance, the more individuals expect to participate in the organizational decision-making process. With reference to negotiations, the relevant questions are these: Are significant power disparities accepted? Are organizations run mostly from the top down, or is power more widely and more horizontally distributed?

Uncertainty Avoidance (Tolerance for Uncertainty): Uncertainty avoidance concerns the degree to which people in a country prefer structured over unstructured situations. At the organizational level, uncertainty avoidance is related to such factors as rituals, rules orientation, and employment stability. As a consequence, personnel in less structured societies face the future as it takes shape without experiencing undue stress. The uncertainty associated with upcoming events does not result in risk avoidance behavior. To the contrary, managers in low uncertainty avoidance cultures abstain from creating bureaucratic structures that make it difficult to respond to unfolding events. But in cultures where people experience stress in dealing with future events, various steps are taken to cope with the impact of uncertainty. Such societies are high uncertainty avoidance cultures, whose managers engage in activities such as long-range planning to establish protective barriers to minimize the anxiety associated with future events. With regard to uncertainty avoidance, the United States and Canada score quite low, indicating an ability to be more responsive in coping with future changes. But Japan, Greece, Portugal, and Belgium score high, indicating their desire to meet the future in a more structured and planned fashion. The pertinent question for cross-cultural negotiations is this: How comfortable are people with uncertainty or unstructured situations, processes, or agreements?

Individualism Versus Collectivism: Individualism denotes the degree to which people act as individuals rather than as members of cohesive groups (i.e., from collectivist to individualist). In individualistic societies, people are self-centered and feel little need for dependency on others. They seek the fulfillment of their own goals over the group’s goals. Managers belonging to individualistic societies are competitive by nature and show little loyalty to the organizations for which they work. In collectivistic societies, members have a group mentality. They subordinate their individual goals to work toward the goals of the group. They are interdependent on each other and seek mutual accommodation to maintain group harmony. Collectivistic managers have high loyalty to their organizations and subscribe to joint decision making. The higher a country’s index of individualism, the more its managerial concepts of leadership are bound up with individuals seeking to act in their ultimate self-interest. Great Britain, Australia, Canada, and the United States show high ratings on individualism; Japan, Brazil, Colombia, Chile, Costa Rica, and Venezuela exhibit very low ratings. A negotiator should determine whether the culture of the other party emphasizes the individual or the group.

Masculinity (Harmony Versus Assertiveness): Masculinity relates to the degree to which “masculine” values such as assertiveness, performance, success, and competition prevail over “feminine” values such as quality of life, maintenance of warm personal relationships, service, care for the weak, and solidarity. Feminine cultures value “small as beautiful” and stress quality of life and environment over materialistic ends. A relatively high masculinity index for the United States, Canada, and Japan is prevalent in approaches to performance appraisal and reward systems. In low-masculinity societies such as Denmark and Sweden, people are motivated by a more qualitative goal set as a means to job enrichment. Differences in masculinity scores are also reflected in the types of career opportunities available in organizations and associated job mobility. For cross-cultural negotiations, a negotiator should know if the culture emphasizes interpersonal harmony or assertiveness.

Years later, Hofstede added a fifth cultural dimension, namely long-term orientation versus short-term orientation. Long-term orientation societies value perseverance, thrift, large savings, and face-saving, among others. In contrast, short-term orientation societies value mainly quick results: spending, low savings, and social obligation by “keeping up with the Joneses”. The long-term orientation index for East Asian countries is high while most Western societies have lower ratings. This cultural dimension allows negotiators to adapt their initial proposals and counterarguments in light of the other party’s long-or short-term orientation.

Managers negotiating in cross-cultural settings can use either of the two frameworks mentioned previously to gain deeper cultural understanding of the society in which they negotiate. Hall’s and Hofstede’s books, referred to here, are easy to read and are highly recommended for those who are negotiating globally.

Players and Process

Negotiators are the people who represent their organizations in striking business deals. While it is important to learn about culture and negotiating style, it may be more crucial to know about the organization that negotiators belong to and the process they must follow in seeking final approval of the agreement. A meaningful business agreement goes through a hierarchy of individuals in an organization before it is finalized. Therefore, it is useful to find out who the individuals who might influence the negotiation outcome are, what role each individual plays, and what the informal networking relationships between the individuals that might affect the negotiation are.9

Key Individuals

Key individuals refer to those people inside and outside the company whose approval must be sought before a negotiated deal is finalized. It is essential that the attitude of key individuals toward particular types of agreements be thoroughly examined before beginning to negotiate. For example, in the United States, any large deal must be approved by the company’s top officers and the board, as well as the Securities and Exchange Commission, the Federal Trade Commission, the Justice Department, and others. Similarly, in Germany, labor unions must be taken into confidence before a deal goes through. In Europe, the European Union can become a stumbling block in many cases. For example, General Electric’s management was shocked by the concerns raised by the EU about competition relative to the company’s acquisition of Honeywell.

In developing countries, different government departments must clear a business deal before it is approved. In some cases, even nongovernment organizations (NGOs) can derail a deal. Thus, a negotiator should compile a list of all individuals who have a say in an agreement.

Decision Process

Equally important is the need to understand the role each individual is likely to play in the approval process. What particular aspects of the deal is an individual concerned with? Who has the authority to override the concerns a person might raise? What kind of information can be used to generate a favorable response from different individuals?

Informal Influences

Many countries have webs of influence that are more powerful than the formal bosses. These influences may not have formal standing, but they can make or break negotiations. A negotiator should determine the role of such influences and factor them into his or her negotiation approach.

The following illustration shows the significant role informal influences can play. A U.S. electrical goods manufacturer entered a joint venture with a Chinese company and hired a local manager to run the Chinese operation. The company tried to expand its product line, but the Chinese manager balked, insisting there was no demand for the additional products. The U.S. management team tried to resolve the dispute through negotiations. But when the Chinese manager would not budge, the team fired him; however, he would not leave. The local labor bureau refused to back the U.S. team, and when the U.S. executives tried to dissolve the venture, they discovered they could not recover their capital because Chinese law dictates that both sides need to approve a dissolution. A foreign law firm, hired at great expense, made no headway. It took some behind-the-scenes negotiation on the part of a local law firm to finally overcome the need for dual approval—an outcome that demanded local counsel well versed in the intricacies of Chinese culture.10

Simply knowing the individuals who are involved in the process is not enough. When negotiating with people, a negotiator is typically seeking to influence the outcome of an organizational process. The process takes different shape in different cultures. Besides, different processes call for radically different negotiation strategies. This means a negotiation approach should be carefully crafted depending on the individuals involved and the process they follow.

Traits for Coping with Culture

Knowledge about the culture of one’s counterpart helps a negotiator to communicate, understand, plan, and decide the deal-making aspects effectively. But culture is a broad field, and there are hundreds of cultures in the world. No executive who negotiates internationally can cope with the cultural challenge no matter how skilled and experienced he or she is. To make the job easier, the following discussion presents the traits that are commonly faced in cross-cultural negotiations.11 When a negotiator learns to deal with them, he or she can gain sufficient cultural training for negotiating.

Negotiating Goal: Contract or Relationship

In some cultures, negotiators are more interested in short-term deals, such as in the United States. Therefore, for them, a signed contract is the goal. In other countries, the emphasis is on building long-term relationships. A case in point is Japan, where the goal of negotiation is not a signed contract, but a lasting relationship between the two parties.

A negotiator must determine if his or her goals match the goals of the other party. It is difficult to close a deal if the goals differ.

Basically, there are two approaches to negotiations: win-win and win-lose. If both parties view the negotiation as a win-win situation, it is easier to come to an agreement since both stand to gain. If one party sees the negotiation as a win-lose situation, it may be difficult to strike a deal because the weaker party believes its loss is the other party’s gain. The stronger party can take the following steps to soften the attitude of the opponent: (1) Explain the perspectives of the transaction fully since the other party might lack the sophistication to understand the nitty-gritty of the business deal being negotiated. (2) Determine the real interest of the other party through questioning. This may require the negotiator to understand the other’s history and culture. (3) Amend the proposal to satisfy the interest of the other party.

Personal Style: Informal or Formal

The negotiating style of the individuals can be informal or formal. Style here refers to the way a negotiator talks, uses titles, and dresses. For example, North Americans believe in informality, addressing people by their first name in an initial meeting. Germans, on the other hand, maintain a formal attitude. In this matter, the guest should adapt his or her attitude to be in line with the host.

Communication: Direct or Indirect

In cultures where communication is direct, such as Germany, a negotiator can expect direct answers to questions. In cultures that communicate indirectly (Japan, for instance), it may be difficult to interpret messages easily. Indirect communication uses signs, gestures, and indefinite comments, which a negotiator must learn to interpret.

Sensitivity to Time: High or Low

Some cultures are more relaxed about time than others. For North Americans, time is money, which is always in short supply. Therefore, they like to rush through a negotiation to obtain a signed contract quickly. Mexicans, as an example, are more relaxed about time. Thus, a Mexican dealing with a North American may view the latter’s attempt to shorten the time as an effort to hide something. Thus, negotiation sessions should be planned and scheduled such that the pace of discussions is appropriate.

Emotions: High or Low

Some negotiators are more emotional than others. A negotiator should establish the emotional behavior of the other party and make appropriate adjustments in negotiation tactics to satisfy such behavior.

Form of Agreement: General or Specific

Culture often influences the form of agreement a party requires. Usually, North Americans prefer a detailed contract that provides for all eventualities. Chinese, however, prefer a contract in the form of general principles. When a negotiator prefers a specific agreement while the other party is satisfied with general principles, the negotiator should carefully review each principle to make sure it is, in any event, not interpreted in such a manner that he or she stands to lose significantly.

Building an Agreement: Bottom-Up or Top-Down

Some negotiators begin with agreement on general principles and proceed to specific items, such as price, delivery date, and product quality. Others begin with agreement on specifics, the sum of which becomes the contract. It is just a matter of style. If a negotiator prefers a bottom-up approach and the other party is satisfied with general principles (i.e., a top-down approach), the negotiator should seek specific information about various aspects before closing the deal.

Team Organization: One Leader versus Consensus

In some cultures, one leader has the authority to make commitments. In other cultures, group consensus must be sought before agreeing to a deal. The latter type of organization requires more time to finalize an agreement, and the other party should be prepared for the time it may take.

A negotiator must examine the attitude of the other party about risk. If the negotiator determines that the other party is risk-averse, he or she should focus the attention on proposing rules, mechanisms, and relationships that reduce the apparent risks in the deal.

Summary

When people negotiate with someone outside their home country, culture becomes a significant factor. It is because people from different cultures present a different perspective in everything they do. Thus, their negotiating style, skills, and behavior vary. More specifically, culture affects the definition of negotiation, the selection of negotiators, protocol, communication, time, risk propensity, group versus individual emphasis, and the nature of agreement.

From the viewpoint of cross-cultural negotiator, the necessary cultural knowledge is grouped into two categories: (1) traditions and etiquette, and group behavior (or protocols and deportment, and deeper cultural characteristics), and (2) players and process.

Protocols and deportment deal with greetings, degree of formality, gift giving, touching, eye contact, emotions, silence, eating, body language, and punctuality. Two frameworks are suggested for deeper cultural understanding: one by Edward Hall and the other by Geert Hofstede. Either one can be used to gain deeper insights into a culture. Furthermore, it is important to know the players and to learn their negotiation process. This requires knowing the key individuals who can impact the negotiation; the role each individual plays; and the informal influences, those who carry weight in the negotiation process. Cultural traits that affect negotiations include negotiating goals, negotiating attitude, personal style of the negotiator, communication style, sensitivity to time, emotional makeup, form of the agreement, structure of the agreement, authority to commit, and risk taking.