Contract is an agreement that is binding on the weaker party.

—Frederick Sawyer

Today’s business executives are finding it more and more difficult to negotiate “static” agreements that withstand the pressure of change. As a result, renegotiations are a growing trend in international business. Every day, companies operating in the global arena sign agreements expected to be mutually beneficial and long-lasting. Despite good intentions and ironclad contracts, unexpected difficulties do arise once contracts are under way, making renegotiations essential.

Too often, at the time of closure, parties assume that the negotiations are over and that both sides can look forward to a successful outcome. In reality, negotiations are only the beginning. A negotiation is not complete until the agreement is fully implemented. With so many unexpected changes occurring in the global marketplace, smooth implementation is the exception rather than the rule.

Although the main purpose of entering into a business deal is to make a profit, frequently contracts turn out to be unprofitable. The parties may also have different interpretations about their respective responsibilities. Thus, continuous monitoring of an agreement is important. And when difficulties arise, parties should not hesitate to undertake renegotiations.

Reasons for Renegotiation

Anecdotal evidence shows that renegotiations are more prevalent in international business than in domestic deals. This is because international business negotiation involves situations not present in domestic settings. When one party believes the deal has become overly burdensome or unreasonable due to changes beyond his or her control, the party considers renegotiation as a distinct possibility over outright rejection. The situations that can lead to renegotiations are examined below.1

Dimensions of International Business Environment

International business deals are susceptible to political and economic changes, which are different from those that result when business is conducted at home. Politically, a country may face internal strife, such as civil war, a coup, or a radical shift in policy. On the economic front, currency devaluation or a natural calamity can create conditions not conducive to fulfilling a negotiated deal.

Mechanisms for Settling Disputes

If the other party to the negotiation does not have effective access to the legal system in the negotiator’s country, the negotiator may believe he or she has little to lose by not implementing a burdensome deal. Under such circumstances, renegotiation is a satisfactory solution in order to keep the deal alive.

Involvement of Government

In developing countries in particular, international business often entails dealing with government departments or with a public sector corporation, a company that is owned and operated by a government. Governments may refuse to abide by a contract, which they, at a later date, consider burdensome. They may force renegotiation for the sake of the welfare of their people or in the name of their national sovereignty.

Cultural Differences between Nations

Doing business with diverse cultures requires extra care in ensuring full understanding of an agreement’s content. For instance, in countries where contracts are lengthy and detailed, little or no flexibility is allowed. In such cases, all possible events that could affect the deal over the period of the contract are identified and appropriate clauses are included in the agreement. To avoid deviations, penalties for noncompliance are built in to ensure strict adherence.

Some cultures are more likely to consider the contract as the beginning of a business relationship. In these cultures, the possibility of reopening the discussions is rather high. Because interpretations can vary due to different cultural views of the negotiation process, negotiators doing business with a different culture seriously consider the follow-up phase and eventual post-negotiation discussions.

Reducing the Need to Renegotiate

In today’s dynamic global market, it is difficult to avoid renegotiating business agreements. Negotiators can, however, reduce the frequency and extent of renegotiations by clarifying all major issues, introducing penalties for noncompliance, insisting on regular meetings to monitor implementation, and explaining the negative impact problems can have on future business opportunities. Doing this should alert both parties to their responsibilities and risks.

Conducting business in different parts of the world requires alternative negotiating approaches. In some cultures, negotiations do not end with the signing of an agreement, but continue throughout the duration of the relationship. So that business can take place in these environments, the contract should include built-in early warning signals to detect the presence of problems. Instead of insisting on a detailed, lengthy contract leaving nothing to chance, a shorter agreement acknowledging the possibility of eventual amendments may be more appropriate. Penalties or similar deterrents should be included, however, to avoid potential abuses in critical areas of the agreement.

For instance, when a manufacturer requests an order of spare parts that is larger than the supplier expects, the supplier should consider it a warning signal. Perhaps the equipment is not being used properly or maintenance is inadequate. In this example, the supplier can review clauses concerning warranty, responsibility for repairs, supplying of spare parts, and other matters relating to equipment breakdown. The manufacturer can offer to train operators on proper use of the equipment, adapt the operations manual to local conditions, translate the manual into the language of the user, or agree to participate in the maintenance of the equipment during the initial installation phase. By taking these additional precautions, both parties can look forward to the execution of the contract with minimum difficulty.

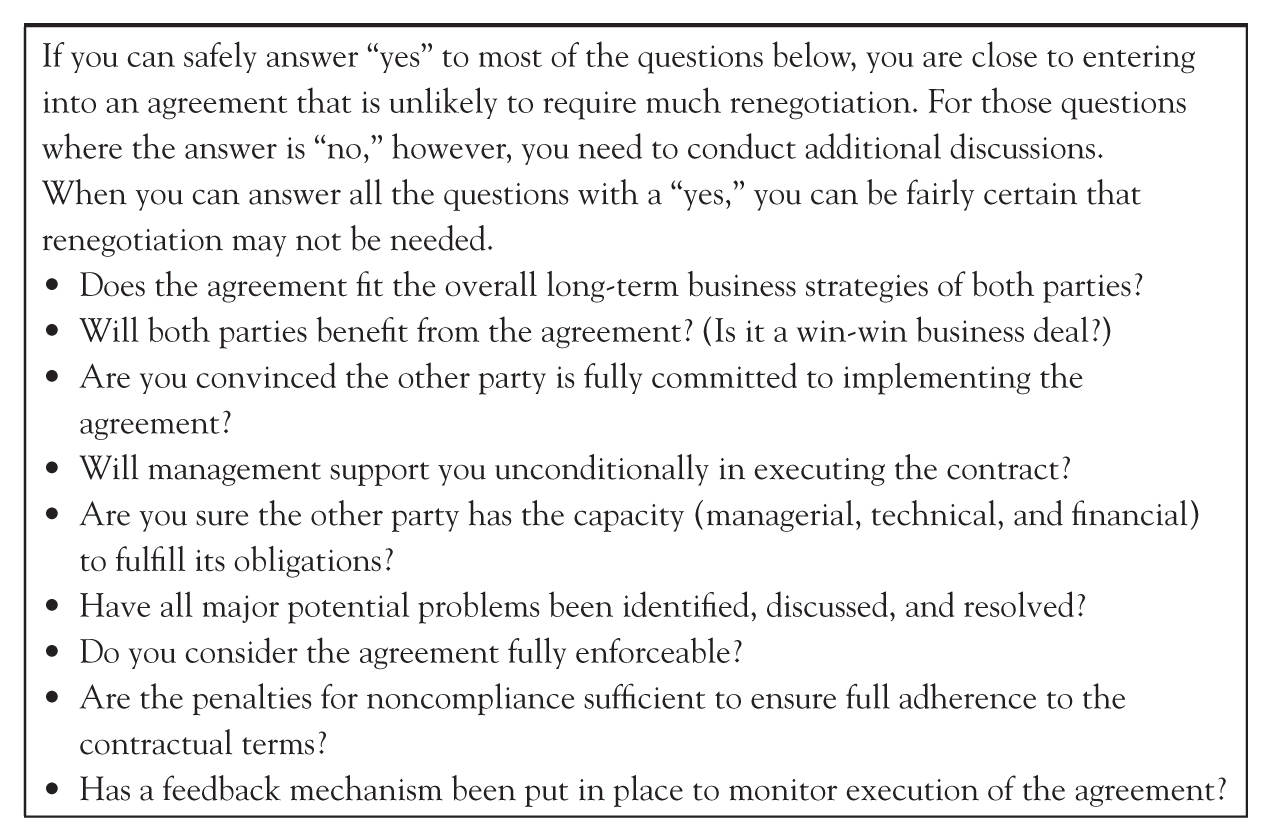

A question most experienced international negotiators ask themselves at the time of closing is, “What does the contract mean to the other party?” In other words, is it the beginning or end of negotiations? Another key question to be raised toward closing is, “How much is the other party committed to the agreement?” Answers to these and other questions can alert the negotiator to potential problems likely to arise during the life of the contract. Such probing at “closing” should help reduce the need for renegotiation. A more thorough examination is presented in Figure 9.1.

Figure 9.1 Reducing the need to renegotiate

Source: Claude Cellich, “Contract Renegotiations,” International Trade FORUM, 2/1999, p. 13.

Prevent Renegotiation

Renegotiation can be prevented (or at least minimized) if both parties anticipate the problem ahead of time and make due provision. Another underlying principle relative to renegotiation is this: If costs to the other party of rejecting an agreement are less than fulfilling, the risk of repudiation and renegotiation goes up. Thus, as a matter of strategy, to give stability to an agreement, a negotiator should make sure that sufficient benefits accrue to the other party in order to keep the deal alive. To implement this strategy, a negotiator should follow these steps:

• Lock the other party in. This is accomplished by including detailed provisions and guarantees for proper implementation. The agreement should have built-in mechanisms to reduce the likelihood of rejection and renegotiation. These mechanisms either raise the cost to the other party for not fulfilling his or her obligations under the contract or provide compensation for the negotiator for having lost the benefit of the agreement he or she made. The two popular mechanisms for this purpose are performance bond and linkage. Under the performance bond, the other party or some reliable third party (multinational bank, investment house) allocates money or property that is turned over to the negotiator if the other party fails to perform. The linkage mechanism involves increasing the costs of noncompliance to the party that fails to implement the deal. An example of linkage is the formation of an alliance of several banks to finance a project in a developing country. The developing country may find it difficult to go against the entire alliance group by noncompliance of the agreement. The country will find the cost of losing its credibility detrimental to future development plans.

• Balance the deal. A successful deal is one that benefits both the parties. Thus, a negotiator should make sure the deal leads to a win-win agreement. If the agreement is mutually beneficial, neither party will consider noncompliance. A balanced deal allocates risks according to the strengths of the parties and not merely on the basis of bargaining power. In addition, unexpected windfalls or losses should be shared by both parties.

• Control the renegotiation. This amounts to specifying a clause in the agreement for periodically undertaking intradeal renegotiation on issues that are susceptible to change. In other words, a negotiator should have a provision in the negotiated deal for opening up the deal and undertaking negotiations at defined intervals. It is better to recognize the possibility of renegotiation at the outset and specify a procedure for conducting it. An intradeal negotiation is examined later in this chapter.

Experienced international business executives include potential renegotiation costs in their final offer. Renegotiations can be costly in time and money, and there are ways to build additional costs into the original offer to absorb such future expenses.

One possibility is to separate implementation into several stages, with payment made after successful execution of each stage. This type of agreement is appropriate for lengthy and complex contracts, such as initiating a joint venture. The most effective preparation requires access to accurate information of all past transactions. This helps parties eliminate time-blaming each other for deviating from the agreed-upon terms.

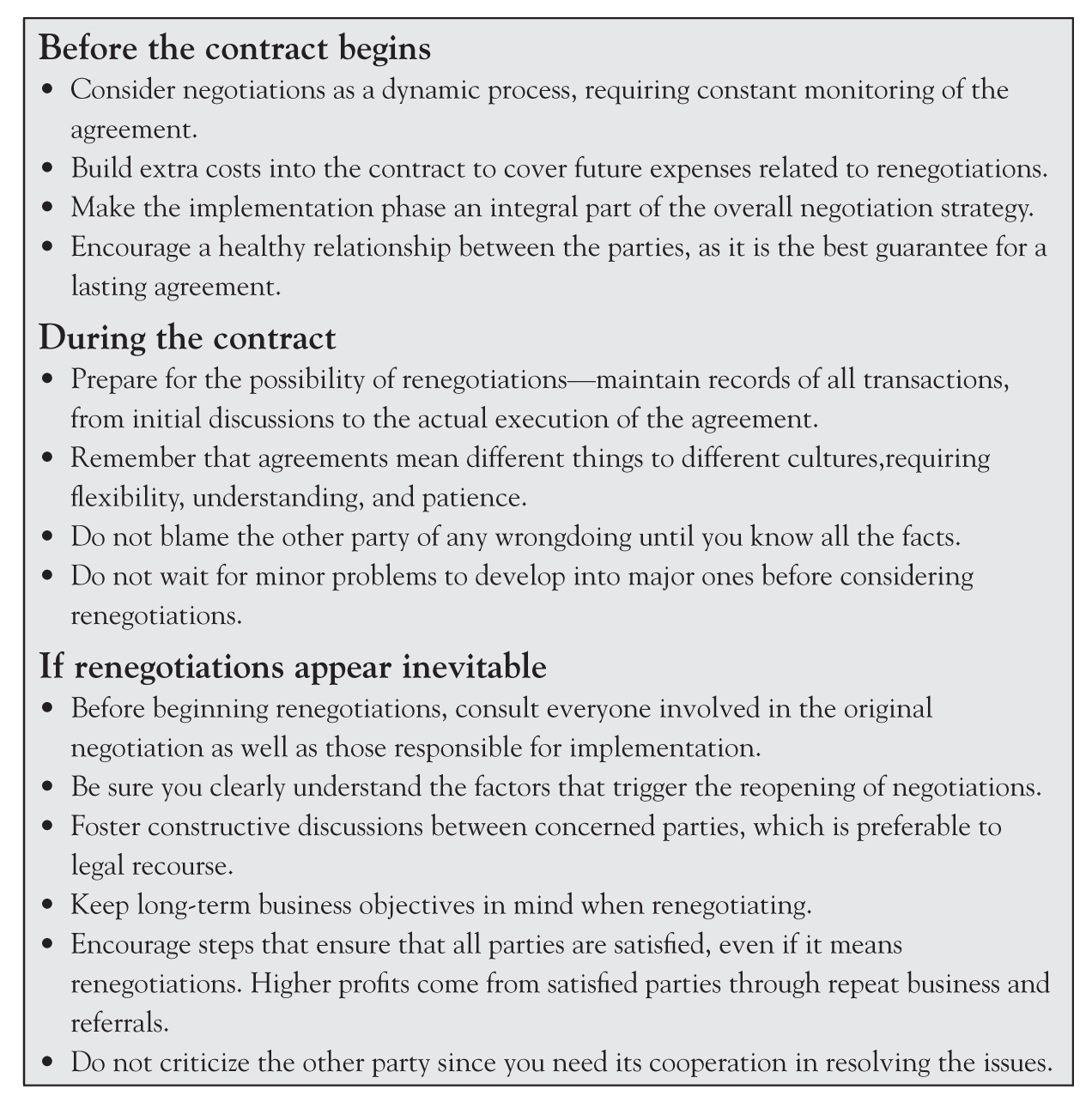

The introduction of penalties for noncompliance is another way to discourage the other party from deviating from the initial agreement. One party giving excessive attention to penalties, however, may indicate his or her lack of confidence in the other party, which could lead to mistrust and resentment. This is hardly the basis for developing a stable business relationship in an ever-changing competitive environment. The key points for dealing with renegotiations are summarized in Figure 9.2.

Figure 9.2 Renegotiation: Key points to remember

Source: Adapted from: Claude Cellich, “Contract Renegotiations,” International Trade FORUM, 2/1999, p. 15.

Overcoming Fear to Reopen Negotiations

More often than not, companies underestimate potential problems that call for renegotiating specific terms contained in an agreement. When something goes wrong, it is only natural that parties get together to resolve the problem. Surprisingly, the party who is the source of the problem is generally reluctant to seek changes or revisions. Often the people in charge of implementation are afraid to address the issue for fear of rejection.

When a business deal is developed in a spirit of cooperation, one party may consider it inappropriate to ask the other party for special conditions, which may be interpreted as taking advantage of the relationship. Fear of receiving a negative answer can lead to missed opportunities for improving the business relationship and fulfilling the agreed-upon terms.

In some cultures, fear of embarrassment is so great that indirect “signals” are sent to indicate the need for revisions. For instance, a sudden lack of communication, vague answers, or an inability to contact the other party, including periods of prolonged silence, may suggest a problem.

As soon as one party sees a problem (for example, products of inferior quality or inability to meet delivery dates), it should take the initiative to contact the other party. It is desirable to take corrective action from the outset by recognizing the problem and suggesting ways of resolving it. Sometimes, lack of international business experience or insufficient knowledge of stringent market specifications means suppliers are not fully aware of what is required to produce top-quality products.

Strict adherence to delivery is another sensitive issue, especially with firms relying on just-in-time inventory. Concerns with delivery are likely to increase in the years ahead as more and more enterprises outsource some of their production and/or services. To minimize problems, executives must maintain open communication lines, make contact early, and be willing to discuss problems openly should they arise.

A real-life example is the case of an Australian furniture importer, who received a large shipment from China in December that exceeded the contract agreement.2 This unexpected shipment resulted in extra storage costs, handling charges, and other indirect expenses. Instead of lodging a complaint or sending back the extra goods, the importer contacted the supplier immediately. It turned out that this huge shipment was initiated by the export manager since this would have given him a large Christmas bonus. After hearing the views of the supplier, the importer explained the economic hardship caused by this shipment and requested compensation on future orders. By doing so, the importer did not antagonize or criticize the other party, but tried to find a workable solution while expressing a commitment to continue the business relationship over the long term.

Types of Renegotiation

It is unrealistic to assume stability of a contract in a rapidly changing global setting. Although negotiators attempt to anticipate the future and make provisions in the contract for eventualities that may arise later on, it is virtually impossible to foresee every possibility. Therefore, business executives negotiating international contracts realize that ongoing discussions and consultations are necessary ingredients for successful outcomes. Thus, renegotiations are unavoidable.

Four different types of renegotiations are used: preemptive, intradeal, extradeal, and postdeal. Each type is relevant under particular circumstances, raises different problems, and demands varying solutions. In any renegotiation, open communications and continuous monitoring are critical to success. Flexibility, commitment, and recognition that renegotiation may be necessary should be part and parcel of a negotiator’s strategy.

Preemptive Negotiation

After a deal has been struck but before it has been implemented, unforeseen events may take place that make it difficult to fulfill the negotiated agreement. Shrewd negotiators control the situation by resorting to preemptive negotiation, that is, renegotiation before the disturbing event happens. Preemptive negotiation requires (a) searching for potential problems, (b) creating a mechanism to manage voluntary change, and (c) establishing a mechanism to settle differences and disputes that threaten relations between the two parties.3

From a business standpoint, the problems fall mainly into three categories: late performance, defective performance, and nonperformance.

• Late performance: Meeting a deadline is the accepted norm in modern-day commerce—goods must be delivered on the appointed day, defects must be corrected promptly, and payments must be made on time. But if a company cannot meet a deadline because of unexpected events at its end (for example, a labor strike) or in the external environment (for example, unavailability of a component), the firm must renegotiate with the other party for late performance.

• Defective Performance: Suppose you negotiated to custom-design furniture and deliver it to an overseas buyer. Subsequently, you ordered components and parts to complete the order. As the product was readied to be shipped, you found problems with one of the components. This forces you to renegotiate with the part supplier to correct the defect, give you a price break on the product with the defective component, or to undertake to supply a new product at a later date.

• Nonperformance: A furniture factory is not able to fulfill an agreement because of a fire at its warehouse. This requires renegotiation with the other party to invalidate the agreement. The renegotiation may nullify the deal, with no compensation due to the other party, or the firm may become liable for damages due to nonperformance.

Intradeal Renegotiation

The most common type of renegotiation occurs within the life of the contract due to the failure of one party to fulfill its obligations. In such cases, known as intradeal, one party seeks relief from its commitments. Another example of intradeal negotiation is when one party wishes to withdraw from the agreement due to its inability to meet the commitments. This type of renegotiation is often found in small- and medium-sized firms entering foreign markets for the first time. Their limited capacity to meet high-quality standards, to produce large quantities, and to meet strict delivery dates forces them to renegotiate the contract or to request cancellation.

Intradeal renegotiations run smoother when the initial agreement contains a clause that permits them. Acceptance at the outset that specific clauses may need to be renegotiated due to unforeseen events goes a long way toward reducing tensions and misunderstandings. In such cases, renegotiation is regarded as a legitimate activity in which both parties can engage in good faith.

The opportunity to renegotiate also arises when both parties establish specific dates or time frames to review an agreement. For example, when a long-term agreement is put in place, both parties may decide to meet at specified times on a regular basis to review the deal based on the experience gained so far. These meetings also identify issues that arise from changing market conditions.

Intradeal renegotiations are used particularly in countries where an agreement is considered to be more of a relationship than just a business deal. Inclusion of intradeal provisions formalizes their way of doing business—during times of change, parties to a negotiation should meet to decide how to cope with the change.

While periodic renegotiation is worthwhile, where deals extend over a length of time, it does have its downside. First, periodic renegotiation increases uncertainty of the terms agreed upon. Second, it raises suspicion that one of the parties might demand renegotiation using changed circumstances as the excuse to gain better terms for itself. Finally, it questions the validity of the agreement since it is open to renegotiation.

Postdeal Renegotiation

Renegotiations can also take place after an agreement expires. There are instances when one or both parties may decide to wait for the expiration of the contract before reentering into new negotiations. Postdeal negotiations may reflect a change in existing business strategies or may indicate that one party is no longer convinced of the benefits in continuing the business relationship.

In a way, the postdeal renegotiation is similar in process to the initial negotiation although there are some crucial differences. First, the two parties have a shared experience of knowing each other. Each party understands the other’s goals, methods, intentions, and reliability, which become a significant input in renegotiation. Second, many concerns relative to risks and opportunities of the deal have been examined and need not be revisited in renegotiation. Third, parties have made investments in money, time, and commitment and are eager to continue the relationship if the result has been mutually satisfying.

Extradeal Renegotiation

This type of renegotiation amounts to dropping the existing agreement and inviting the other party to renegotiate. Generally, there is no provision in the agreement to resort to renegotiation, but if one party claims it is unable to implement the agreement, it may suggest renegotiations. The other party finds accepting renegotiation to be emotionally disturbing because its hopes of expected benefits are shattered. Furthermore, extradeal renegotiations often begin with a feeling of pessimism. In circumstances where renegotiation is the only viable option, parties reluctantly participate as unwilling partners. The environment surrounding extradeal renegotiation is marked with bad feelings and mistrust.

Both parties to the negotiation feel offended. One party thinks the other should appreciate its difficulties and, thus, fully cooperate in renegotiating the deal. The other party feels deprived of the profits expected from the agreement and believes it is being asked to give up something to which it had legal and moral right.

The extradeal renegotiation has a variety of implications for both parties. The party seeking renegotiation may lose credibility in the business community. On the contracts it renegotiates, the other party may demand stricter terms or penalties for noncompliance. The party yielding to renegotiation may gain the reputation of being weak and susceptible to pressure. This can encourage other parties on other agreements to demand renegotiation and better terms. The ripple effect of renegotiation can weaken the yielding party with regard to future deals with other parties.

Approaches To Renegotiation

The following approaches are available for conducting renegotiation.4

• Clarify ambiguities in the existing agreement. This approach entails appending clarification to ambiguities in the existing agreement rather than creating a new agreement. It accepts the validity of the current agreement, but changes are made in it to accommodate an emerging situation. For example, assume an exporter has negotiated to pay for air transportation of goods to a foreign destination. After a few months, there is a worldwide energy crisis, with the price of crude oil doubling every two weeks. The exporter finds that transportation costs have wiped out her profits, and she cannot afford to continue in business unless the importer agrees to renegotiation to relieve her from excessive air transportation costs. An amendment to the main contract is added with the importer absorbing part of the extra cost of air freight. This nominal change is agreed upon without questioning the validity of the original contract.

• Reinterpret key terms. Sometimes terms in an agreement lead to different interpretations based on the background of the parties involved. Under this approach, renegotiation amounts to redefining these terms such that both parties attach the same meaning to them.

• Waiver from one or more requirements of the agreement. As a part of renegotiation, the burdened party is relieved from fulfilling some aspect of the agreement.

• Rewrite the agreement. If all else fails, the parties may be forced into invalidating the existing agreement and renegotiating a new deal.

With intense competition, greater outsourcing, and the increase of electronic commerce, renegotiating business contracts is likely to become the norm rather than the rule. Instead of looking at the implementation stage as a separate entity, successful business executives consider the follow-up phases to be an integral part of negotiating strategies.

Renegotiation of business deals may be necessary and can prove to be more profitable in the long term even if renegotiation offers some temporary disadvantages. Global managers know that relying on a contract alone is unlikely to resolve pending issues. Personal relationships and mutual trust are essential in order to build a solid foundation for repeat business in a highly competitive global environment, particularly when doing business in relationship-oriented cultures. Both parties should keep in mind the long-term benefits of a business relationship when renegotiating existing agreements.

Experienced negotiators keep negotiating even after reaching agreement. In the end, satisfying and retaining current customers—by working together in solving problems through renegotiations—is less expensive and less time-consuming than seeking new partners or entering into costly litigation procedures. Skilled executives know that it is not the agreement alone that keeps a business going, but the strength of the relationship.