Developing an Organizational Negotiating Capability

Negotiation is a core organizational competency.

—Hallam Movius and Lawrence Susskind

Negotiating business deals are becoming increasingly sophisticated and complex, calling for the adoption of an institutional negotiating mindset. To avoid negotiating outcomes that create unnecessary difficulties, negotiators take an integrated institutional framework instead of the ad hoc, short-term, case by case approach. The need to improve the efficiency of organizations negotiating capabilities has been the subject of research in the past decade.1 As negotiations are becoming more demanding, business executives having access to an in-house organizational culture and capability can look forward to limit risks while negotiating mutually beneficial outcomes.

To build, develop, and maintain an organizational negotiating culture, management commitment is essential. Despite management willingness to build its own organizational negotiating capability, negotiators tend to abandon the institutional approach by switching to an ad hoc style based mainly on competitive tactics. By failing to consider the overall benefits, these firms are likely to face difficulties in the implementation phase, resulting in endless problems, additional costs, and lower profits over the life of the agreement. A successful negotiation reflects not only an excellent preparation but how well the agreement is implemented.

To reach superior and sustainable outcomes, negotiators take a long-term view and expand the number of issues to be negotiated by focusing on common/complimentary interests. In most negotiations, decisions are based on both tangible benefits (economic gains) and intangible ones (noneconomic). Lately, intangibles have become increasingly valuable, particularly in knowledge based industries as well as in highly competitive markets and in traditional societies as they can make the difference between reaching a deal or not. In most relationship-oriented cultures, negotiators may be willing to consider taking a business risk but will be reluctant to risk a relationship. In case negotiators do not have an existing relationship with their counterparts, they can rely on the services of intermediaries.

As mentioned above, a shift from treating negotiation as a spontaneous activity to a collective and coordinated undertaking is starting to take hold. This is particularly beneficial to enterprises doing business in emerging economies where past experiences, trust, and personal ties play a dominant role in reaching agreement. Adopting the institutional approach requires the full commitment of all stakeholders throughout the negotiation process including the postnegotiating phase.

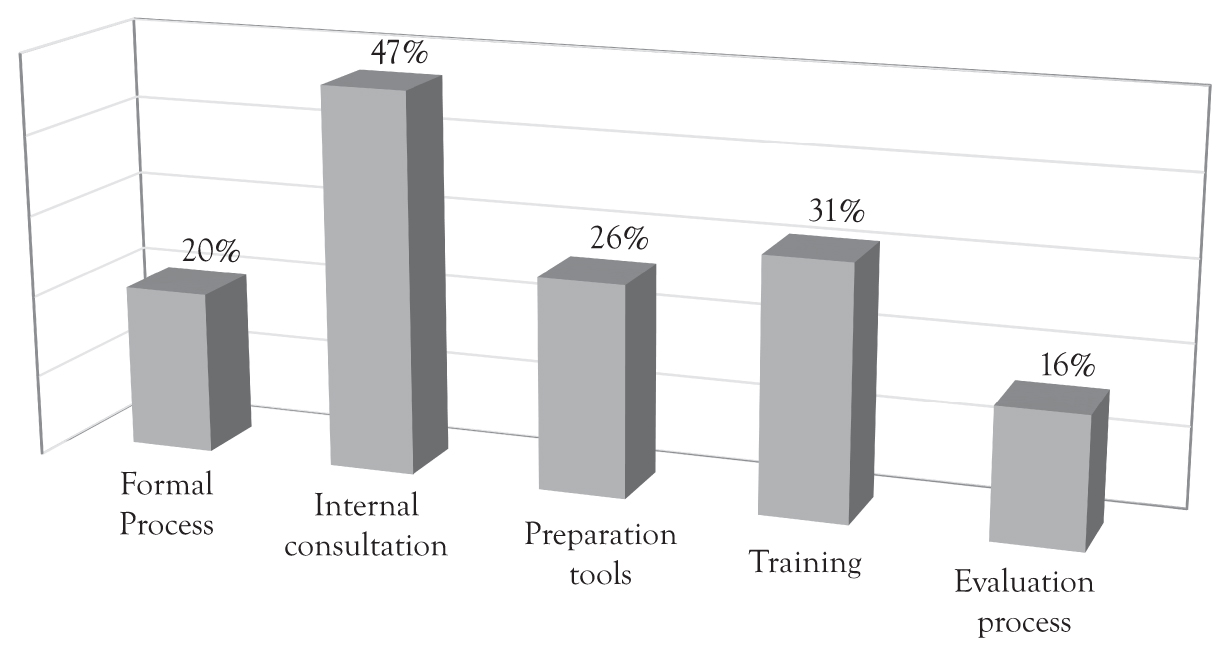

A 2009 benchmark study of the world’s largest organizations by Huthwaite International and the International Association for Contract and Commercial Management (IACCM) shows that 80 percent of the responding firms had no formal negotiation process. Moreover, only half of the companies had a system for cross organizational interface. Concerning negotiation planning tools, nearly three out of four firms did not have them. With regard to authority approval from higher management, no more than 50 percent of the firms had formalized it. As far as training is concerned, only one-third of the firms had their employees receiving some sort of training or retraining, mostly of a general nature. To be effective however, training has to reflect employee needs and has to be linked to corporate objectives while taking into account the competitive environment the firm is operating in.

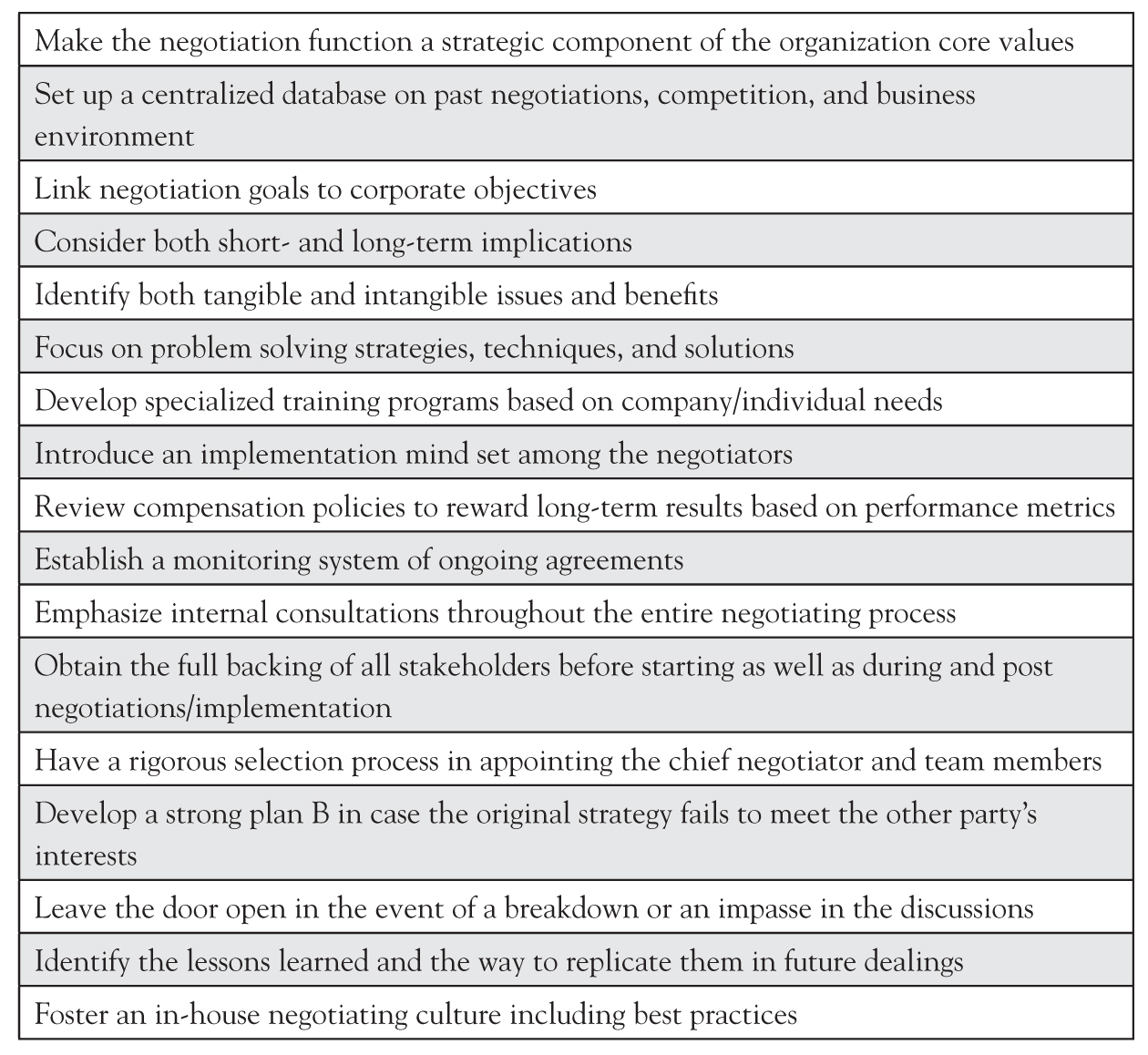

When it came to measuring the performance of their negotiations, over 80 percent of organizations had no established procedures for evaluation. Finally, the survey found that those firms having set up an organizational negotiating capability registered significant improvements in net income, while those firms without a formal negotiation process experienced a drop in profitability. Figure 13.1 below illustrates the areas where corporations have introduced an organizational negotiating capability.

Figure 13.1 Organizations having an in-house negotiating capability

Source: Adapted from “Improving Corporate Negotiation Performance: a Benchmark Study of the World’s Largest Organizations”, Huthwaite International & International Association for Contract and Commercial Management, 2009, UK.

The above findings point out that business executives having access to an organizational negotiating capability achieve higher outcomes. In other words, negotiation is not just an individual capability but an organizational one.2 Organizations experiencing high staff turnover or operating in rapidly changing and competitive business environments would benefit from having an internal negotiating culture and capability.

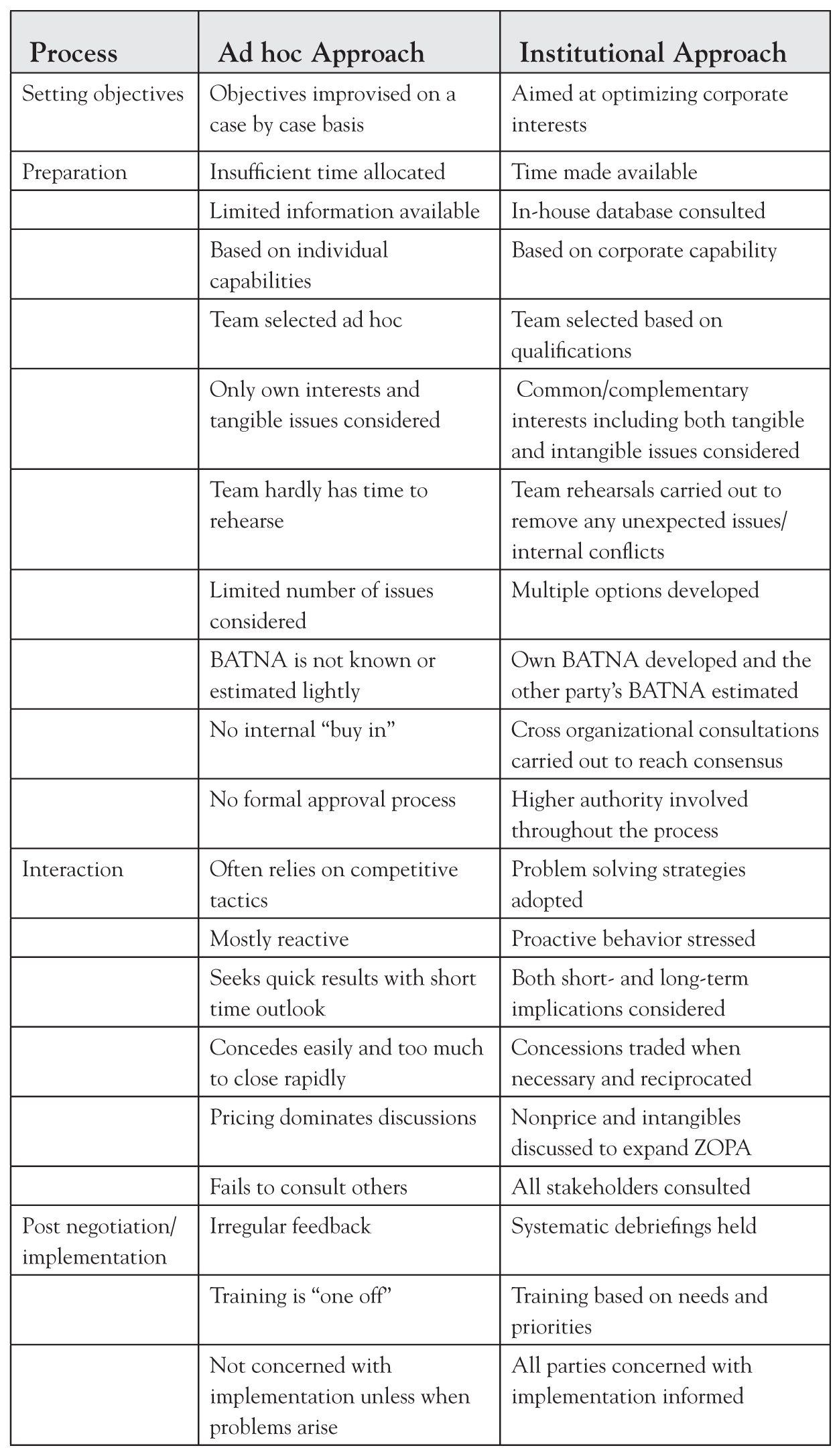

Comparison of Negotiation Processes

To highlight the major differences between ad hoc negotiations and institutional ones, Figure 13.2 compares these two approaches in terms of setting objectives, preparation, interaction, and postnegotiation/implementation phases.

Figure 13.2 A Comparison of ad hoc and institutional negotiation approaches

Source: Adapted from D. Ertel (1999), “Turning Negotiation into a Corporate Capability,” Harvard Business Review, May/June, p.68.

As success in any negotiation depends on the quality of its preparation, it becomes essential for organizations, particularly those competing globally, to build an in-house negotiating culture and capability. To do so, management sets up an organizational infrastructure that recognizes negotiation as a strategic core competency coupled with a culture of problem solving and relationship building.3 Furthermore, it would be helpful for negotiators to prepare contingency plans (having a strong plan B) in case the original one does not meet the parties’ interests. As preparing for successful negotiations can represent as much as 80 percent of time it takes to complete a negotiation (excluding post negotiations), negotiators should be allowed to devote all their energy to the task ahead and receive full support from senior management. Preparation consists of multiple tasks that include among others, developing a strategy, planning options and alternatives, setting an agenda, identifying concessions to be traded, finding out the other party’s interests, priorities, and its BATNA, estimating one’s own BATNA, analyzing competition and taking into consideration competitive pressures and how the agreement will be implemented. By establishing a core negotiating capability, organizations provide their executives with access to the latest market information, references to past negotiations, the firm’s position vis-à-vis competition, technical expertise, and the time needed to design appropriate strategies and tactics. This calls for organizations setting up and maintaining an up to date centralized database. Although having access to a database is a significant advantage to organizations, most negotiators fail to utilize it.4

The institutional/integrated approach differs from the traditional ad hoc negotiation model where competitive strategies and short-term benefits prevail. This is best illustrated by the fact that negotiators have access to over one hundred different competitive tactics but only twenty cooperative ones. In relationship-oriented cultures where business deals cannot be discussed openly unless there is a relationship, negotiators need to take whatever time is necessary to establish a relationship based on mutual trust. This is particularly relevant for those firms seeking business opportunities in Brazil, Russia, India, and China (BRIC), and in other emerging markets where relationship matters most. Experience shows that when negotiators are concerned with preserving the relationship, they tend to leave money on the table. However, in the long run, these suboptimum agreements can become a source of additional benefits from repeat orders, expanding business opportunities or referrals, thereby contributing further to their relationship capital.

Insufficient preparation and the lack of an organizational negotiating capability lead to poorly negotiated outcomes. For instance, in international business, as many as 70 to 80 percent long-term agreements have to be renegotiated at one time or another due to unexpected problems or unforeseen market conditions. Concerning negotiations dealing with mergers and acquisitions, over half of all agreements fail within three years. There are many reasons for these failures including the overemphasis on financial returns, underestimating the dangers of excessive debt, neglecting common synergies, and lacking cultural sensitivity. An example of a failed merger is the Chrysler-Daimler, where Chrysler was negotiating a merger while Daimler was seeking an acquisition.5

Structuring In-house Negotiation Capability

By setting up an in-house negotiating capability and promoting best practices, organizations improve substantially their chances of reaching mutual gains that are not only profitable but sustainable. Negotiating global deals require both sides to invest in developing a working relationship and enhance their reputation as world-class organizations. The main elements of an in-house corporate negotiation culture and capacity include the elements shown in Figure 13.3.

Figure 13.3 Main responsibilities of an in-house organizational negotiating capability

Designing an Evaluation System and In-house Database

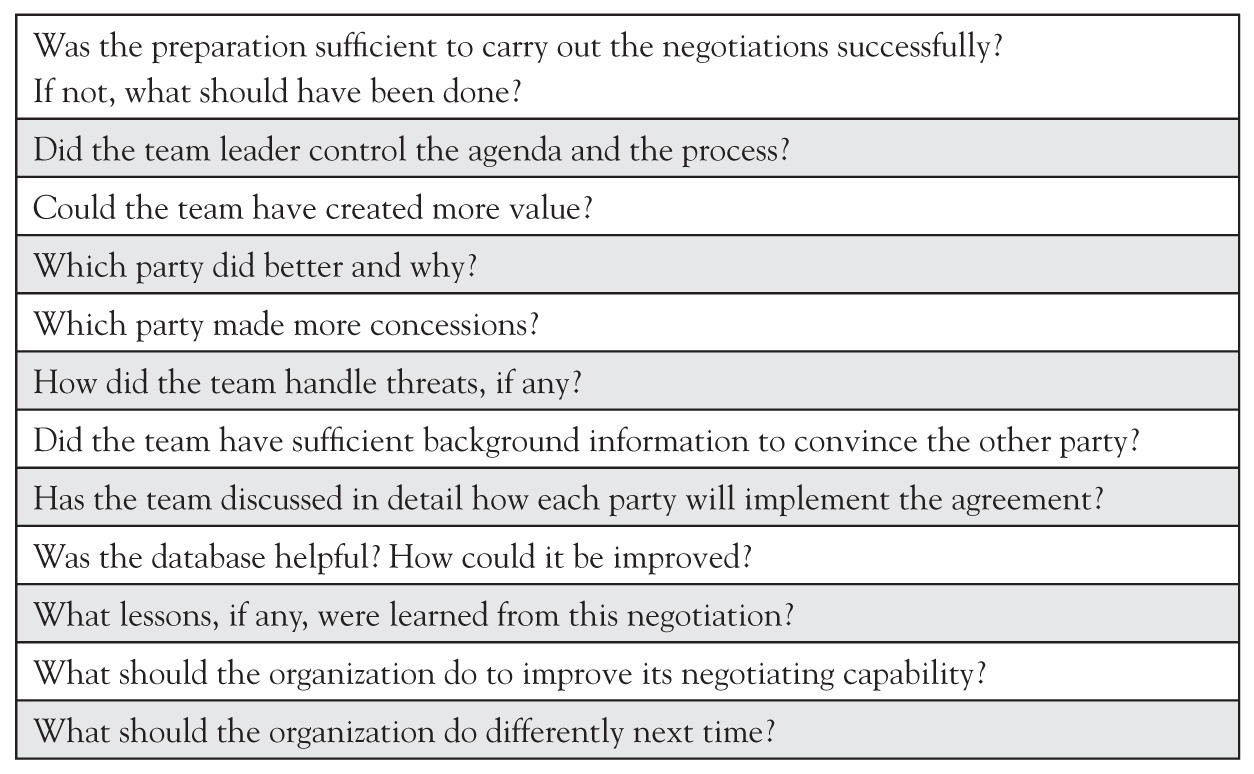

In an organizational negotiating culture, each negotiation completed or failed is the subject of a systematic feedback to record the lessons learned. During debriefings, both the chief negotiator and team members share their experiences with management and implementers, whether they are positive or not as sometimes more can be learned from past mistakes than from successful negotiations. These debriefings have to take place shortly after concluding a negotiation and documented before important information is forgotten. Another advantage of having these debriefings is to let management and the people responsible for implementation know how the discussions progressed, which were the key issues creating difficulties, and how major objections were resolved. On the basis of these discussions, executive summaries are prepared, distributed to all the concerned parties, and entered into a centralized database. Good record keeping is essential, particularly for renegotiating contracts or when having to deal with the interpretation of the various clauses during the implementation phase.6 To be of relevance, evaluations have to be specific and factual, and provide advice on how to avoid future pitfalls. This information is most valuable to new negotiators as well as useful for markets characterized by stiff competition, organizations experiencing high staff turnover, and when negotiating complex deals. The rational for setting up evaluation procedures is not only to improve its negotiating capability, but to develop best practices and enhance the organizational institutional memory. Typical questions to be completed soon after a negotiation are listed in Figure 13.4.

Figure 13.4 Typical evaluation questions

Depending on the company’s structure and commitment, this list can be elaborated further by seeking more detailed information from past negotiations. What is important for organizations is to recognize the importance of having an effective feedback system that contributes to its institutional memory on a regular basis.

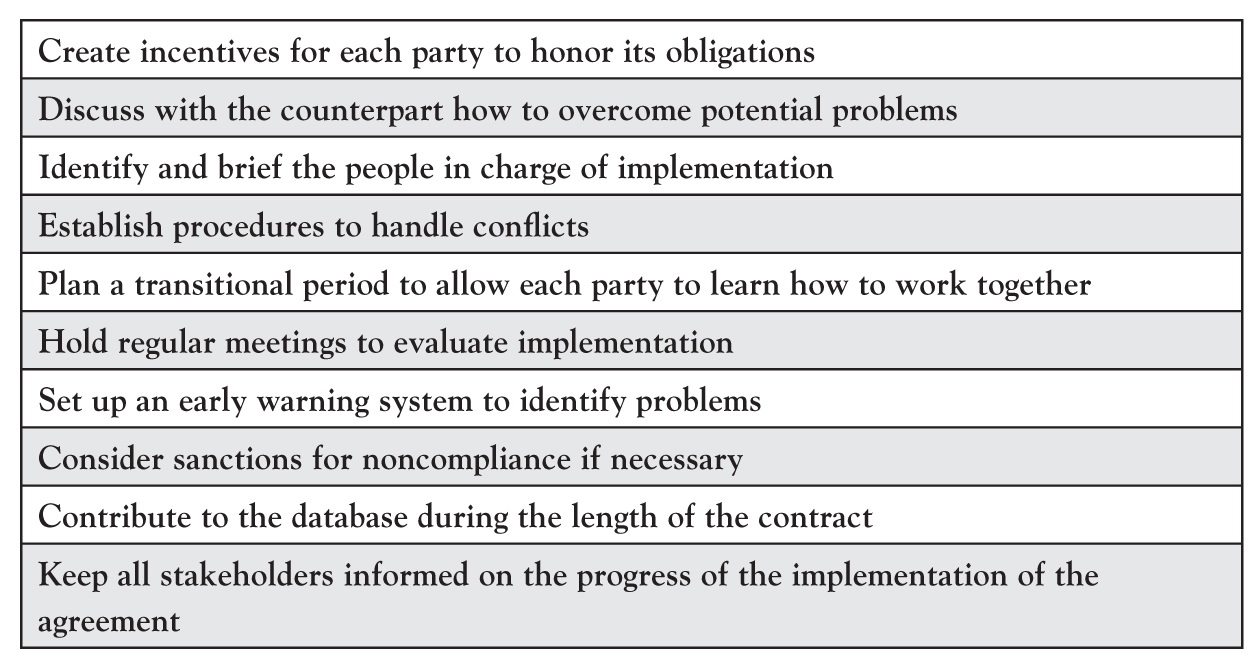

Evaluations may be carried out either by the internal section responsible for evaluation, a special task force, or by an independent evaluator. Generally, evaluations are confidential and not available to the public. There are exceptions, however, when negotiations between multinationals are analyzed for the development of case studies. An example of a case study was the negotiation between Renault and Nissan during an 18 months period in 1998 and 1999. With 15 years of joint operations, the agreement has proved successful for both parties, mainly because Renault’s management paid special attention to Nissan’s concerns about keeping its identity after the agreement. The analysis of the Renault-Nissan negotiations has led to the recommendations listed in Figure 13.5.7

Figure 13.5 Renault-Nissan negotiation highlights

Source: Stephen E .Weiss. Negotiating the Renault-Nissan Alliance; Insights from Renault’s Experience in Negotiation Excellence: Successful Deal Making, Benoliel, 2011.

Implementation Phase

For world-class negotiators, reaching agreement is not the end of the discussions but the beginning of a business relationship. Having negotiated a deal is pointless if it cannot be implemented successfully. To reduce risk of noncompliance during implementation, experienced negotiators consider the following key issues throughout the negotiation process:

Generally, preparing well, acquiring negotiation know-how, improving communication skills, and learning from past mistakes increase negotiating power. However, effective negotiators never stop learning from their past experiences.

Negotiating agreements that do not create difficulties during implementation, particularly in multiyear and complex global deals, are the exception rather than the rule, requiring greater attention to details and constant monitoring. Generally, long-term agreements encounter numerous problems that can be resolved without being confrontational when the parties consider problem solving a joint undertaking due to mutual interests and existing relationships. This requires a shift in negotiating strategies, from an ad hoc approach to an institutional one, and a change of perspectives, from short-term to long-term. This also requires adopting a global implementation mindset. An agreement that satisfies both parties is not only the best guarantee to counter competitive threats but can generate greater profits over the long-term and strengthen the business relationship. Finally, experienced negotiators know that the people involved in implementation want a workable agreement and not problems. World-class negotiators committed to building an in-house negotiating capability and applying best practices are likely to negotiate mutually rewarding and sustainable outcomes while improving the bottom line. In the end, executives adopting an implementation mindset, having access to an organizational negotiating capability, and respecting diverse cultural values can make the difference between success and failure. In other words, successful negotiators possess the following:

• Communication skills

• People skills

• Decision making skills

Effectively combining these three skills are most likely to lead to superior outcomes. For this reason, negotiation is considered more of an art than a science.