The value of intangibles is what the buyer is willing to pay and can be priceless.

—Anonymous

In today’s highly competitive globalized economies, intangibles are becoming an important comparative advantage. In fact, in most businesses, intangibles play an increasing role and are likely to grow in the near future. Too often, negotiators focus on trading tangibles, as they can be easily measured, while neglecting intangibles. Tangibles refer to property, equipment, accounts, receivables, cash, prepaid expenses, copyrights, patents, etc. Intangibles are nonphysical in nature and harder to quantify.1 Intangibles consist of brand, business models, customers’ loyalty, designs, employees’ motivation and retention, goodwill, R&D, software, trade mark, trade secrets and trust, etc. as elaborated in Figure 14.1.

Figure 14.1 Short list of intangibles*

*All the above can have either a positive or negative impact on any negotiations

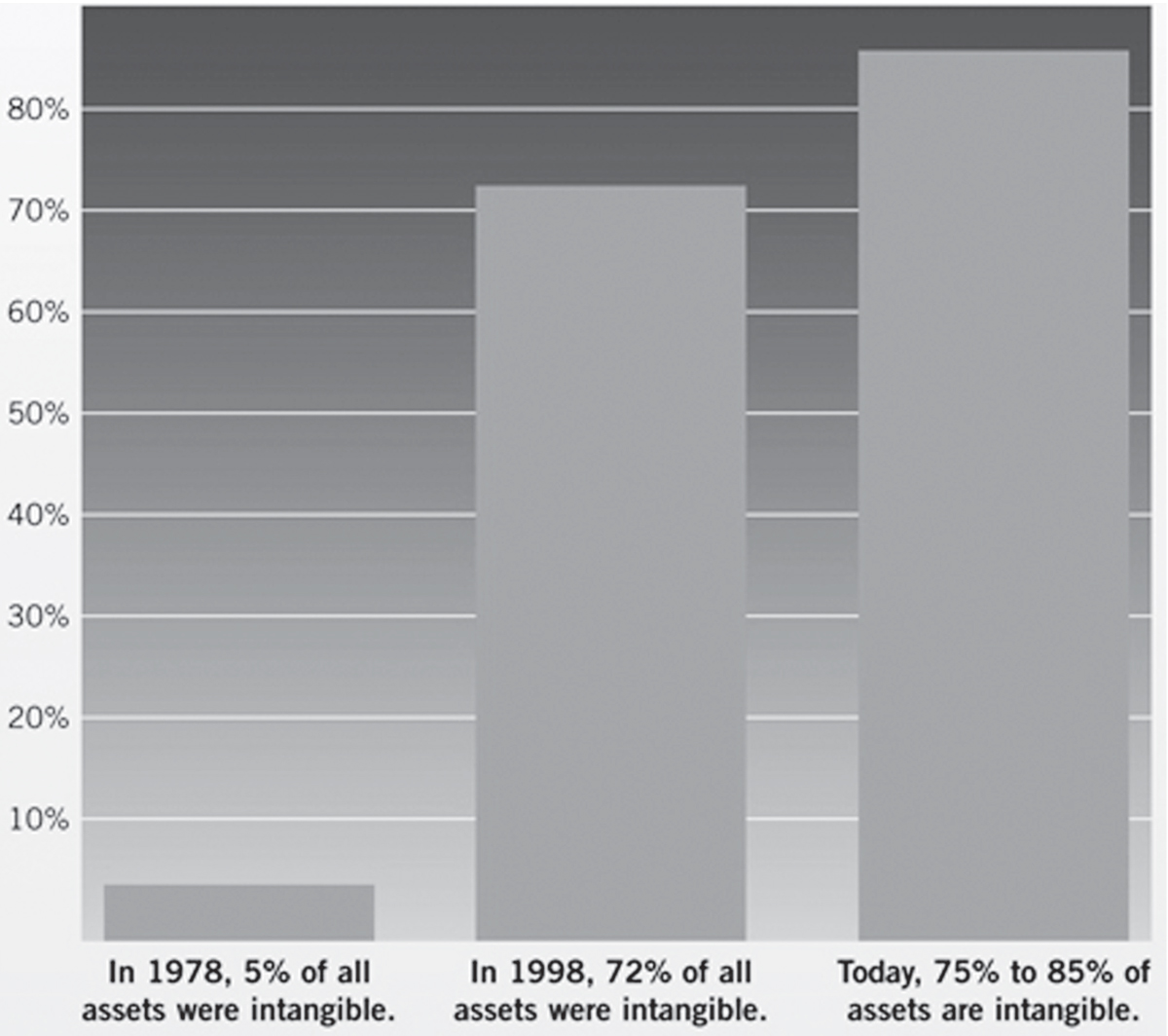

Intangibles also refer to negotiators’ behavior when their underlying psychological motivations may directly or indirectly influence the negotiation.2 Intangibles are relevant in any negotiation, particularly for complex, long-term business deals, in intensive knowledge-based industries, in services, with start-ups, or in cross-cultural contexts. Over the years, intangibles have increased in importance vis-à-vis tangibles. As shown in the Figure 14.2 below, between 1978 and 2015, intangibles assets have increased from 15 to 85 percent of S&P 500 market value. The rise of intangibles is likely to grow faster than tangibles as a result of the Internet revolution and globalization.

Figure 14.2 The Growing significance of intangible assets

Negotiators planning their future negotiations need to explore the type of intangibles that can influence their decisions. The importance of intangibles can vary from one firm to another and from one negotiator to another calling for extra time during preparatory phase.

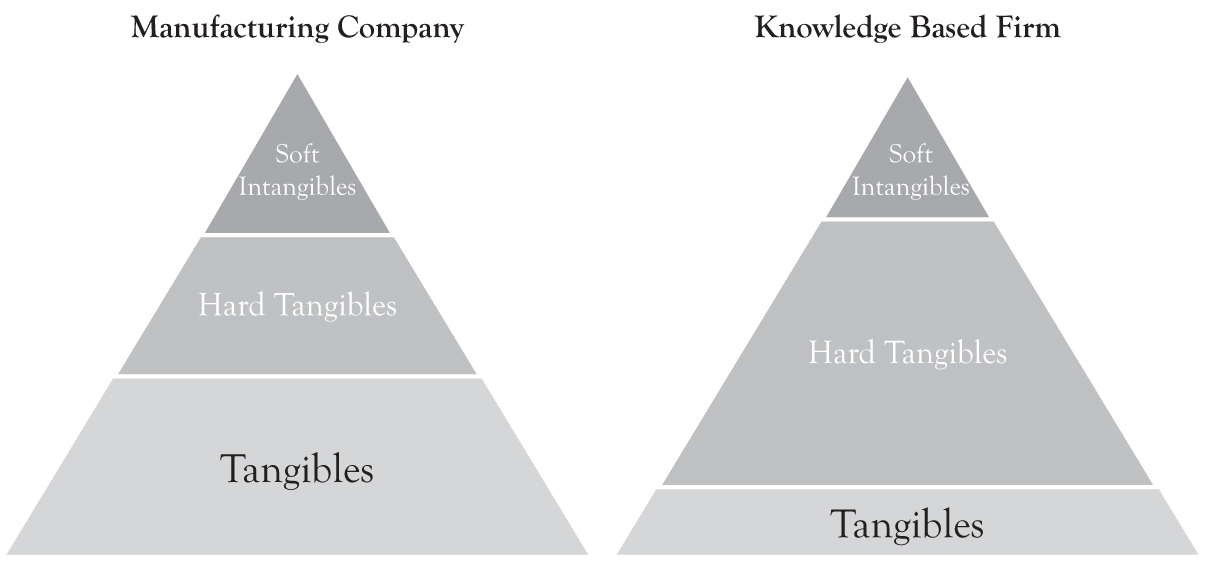

There are two main types of intangibles: hard and soft, as depicted in Figure 14.3.

Figure 14.3 Hard and soft intangibles for different firms

The distribution mix between tangibles and intangibles depends on the type of business and issues being discussed as well as the context. In the case of a manufacturing firm, its tangible assets, consisting mainly of plant and equipment, are likely to be greater than its intangibles. The opposite mix is expected for an Internet start-up where its value is mostly made up of intangibles.

Hard intangibles consist of assets having potential economic value such as market exclusivity, underdeveloped patents, intellectual property rights, and brand recognition. Soft intangibles refer to the firm’s reputation, management commitment, customer’s mailing list, adhering to corporate social responsibility principles, testimonials, and trust among others. Intangibles are also derived from the negotiator’s personal attributes, behavior, and experience.

Of all intangibles, trust among the parties is essential to greater sharing of information and reducing the transaction costs. Trust is critical in any negotiation if the parties are to engage in value creation. In fact, trust is the basis for successful agreements particularly in relationship-oriented cultures. In these cultures, buyers prefer to deal with someone they trust. In addition, intangibles related to the negotiator’s behavior, such as being able to control the discussions, fear of failure, need to look competent, to be seen as the winner and so on can influence the outcome of the discussions. Negotiators from small and medium enterprises (SMEs) can emphasize such intangibles as their ability to make quick decisions, flexibility to shift production schedules rather rapidly, and capability to produce shorter runs. In addition, they can stress their knowledge of the local market, closeness to their customers, lean organizational structure, and low operational costs.

Impact of Intangibles

Intangibles can influence the negotiations either positively or negatively. For instance, negotiators representing firms which have a poor image in the market place or have been forced to recall products due to poor quality, or those firms which are facing financial instability, incurring high management turnover, or experiencing frequent labor conflicts are negotiating from a vulnerable position vis-à-vis their counterparts. Similarly, firms losing market share due to increasing competition, experiencing technology obsolescence, having a low retention of customers, and/or declining profits place their negotiators in relatively weak positions. This list can be expanded when negotiators are dealing across diverse cultures, particularly in relationship-oriented cultures, where failure to acknowledge the other party’s cultural values can lead to an impasse or a breakdown in the negotiations.

Intangibles and Negotiator Background

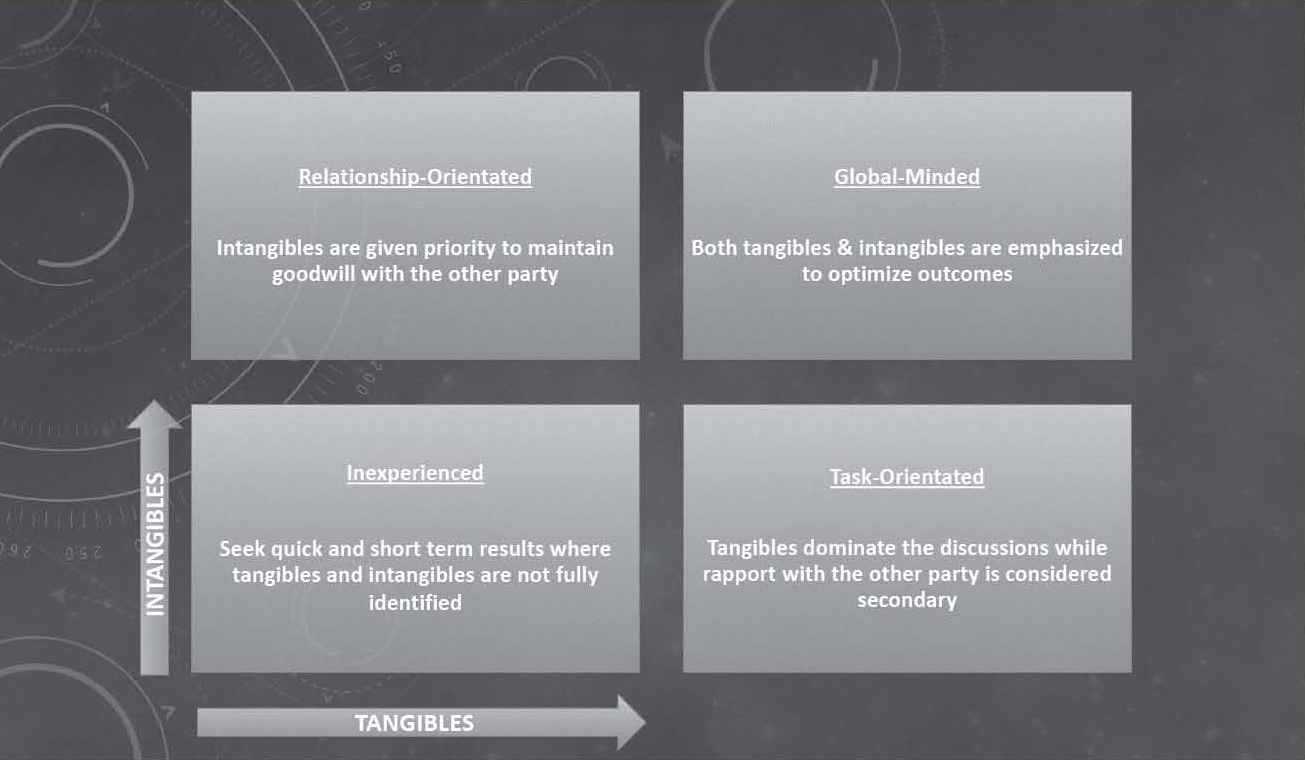

Although all negotiators consider tangibles, and to some extent intangibles, experienced negotiators stress both of them to reach mutually beneficial outcomes. With regard to intangibles, negotiators can be grouped into the following four categories:

• Task-oriented negotiator

• Relationship-oriented negotiator

• Global minded negotiator

The relationship between the four types of negotiators is illustrated in Figure 14.4.

Figure 14.4 Types of Negotiator – Tangibles & Intangibles Matrix

Inexperienced negotiators consider mainly tangible issues, usually based on their own interests. This approach is frequently used in short-term transactions of low value where negotiators look for quick results even if the outcome fails to maximize value and/or leads to the negotiations breaking down. In such cases, preparation is insufficient, not much information is exchanged, and the results are likely to be suboptimal.

Task-oriented negotiators stress value claiming (the substantive issues) at the expense of value creating and building rapport with their counterparts. In these negotiations, trust among the parties is less important to reach agreement and concessions tend to be mostly tangibles in nature. Task-oriented negotiators can be more effective when dealing in certain cultural environments, where the market is highly competitive and at times dominated by large firms.

Relationship-oriented negotiators emphasize rapport and trust when dealing with their counterparts. To them, trust is essential to achieve success. In most cultures, the presence of a healthy relationship is a must if the negotiations are not only to take place but conclude. Concessions contain tangibles benefits and a substantial number of intangibles. This type of negotiator is most effective when negotiating services, with SMEs owners, and in multicultural environments where the human factor plays a critical role. In situations where relationship-oriented negotiators are dealing with task-oriented counterparts, they have to be careful not to concede too many concessions (particularly tangibles) for the sake of maintaining harmony with the other party.

Global minded negotiators invest a great deal of time preparing and interacting with the other party. By being global-minded, negotiators seek to have a “big picture” of all the issues, thus enabling them to create and then claim value based on their counterparts interests and priorities. Tangibles as well as hard and soft intangibles are given high priority. Throughout the negotiations, information is shared, creativity is encouraged, and rapport is promoted. This type of negotiator is more suitable for negotiating high-value transactions and long-term contracts. By taking a comprehensive view of the negotiations, global minded negotiators are in a better position to obtain agreements that are mutually beneficial and can be implemented without major difficulties.

Trading Intangibles

Trading intangibles does influence the negotiations process and outcome. Furthermore, by including intangibles in the discussions, the zone of potential agreement (ZOPA) is expanded when negotiators explore their respective priorities, interests, and underlying needs. For example, in relationship-oriented cultures, a negotiator’s reputation and trust are essential not only for the meeting to take place but for the discussions to progress. As intangibles have different values to different negotiators, it becomes easier to trade them once the wants and interests of the parties are known. This assumes that both parties trust each other and are willing to trade intangibles that do not cost them very much but are highly valued by the other party and vice versa.

An example illustrating the trading of intangibles took place between the owner of a small retail outlet and a large regional one. The owner decided to sell his business due to approaching retirement age, declining profits, and increasing competition. The buyer made an opening offer that seemed reasonable. However, the owner refused it without giving any justification. Despite receiving better offers (the last one representing a premium over the economic value of the retail outlet), the owner still hesitated to accept the offer. By now, the buyer thought that the owner was not interested in the sale. Instead of making a further offer or withdrawing from the negotiation, the buyer switched strategy by turning his attention to the owner’s background, his hobbies, what he would do with his time if he sold the business, and other personal questions until he had a clear understanding of the seller’s underlying interests. From these discussions, it became clear that the retail outlet was more than a business to the owner—it was a lifetime achievement. Besides, he did not wish to severe his ties with its long-term customers and loyal employees as some had been with the firm for decades. In the end, the buyer shifted from a task-oriented strategy to a global-minded one by repackaging the offer that contained not only a fair price for the business but a clause that committed the new owner to hire the senior employees of the small retail outlet. In addition, the owner was given a consulting role for an initial period of three years in the new organization with the possibility of an extension.

As the above example shows, intangibles can have greater value to owners of SMEs as they are emotionally attached to their business. Often, owners of SMEs may not be objective or conscious of their firm intangibles while concentrating all their attention on tangible issues. When buyers negotiate with SMEs, they consider both economic and noneconomic benefits. For instance, owners selling their firm may be offered such intangibles as consultancies, an advisory role, an honorary title, the opportunity to keep in touch with their long time and loyal customers, maintaining the name of the firm, keeping the firm facility in the same location, as well as protecting the employee rights and benefits. These and many other intangibles allow the negotiators to discuss multiple options besides economic values that could bring them closer to agreement.

Intangibles and Future Outlook

Negotiating is more than reaching an agreement. It is an opportunity for each party to work together toward a common objective. Often, it is the lack of trust, the absence of a working relationship, and poor communications among the parties that result in conflicts. For example decisions made by the automobile manufacturers giving preference to economic aspects at the expense of intangibles have a negative impact on their profits. The replacement of defective parts, the payment of fines, legal expenses, and damaged reputation could have been avoided by including intangibles and tangibles during the negotiations. By considering suppliers as partners and developing long-term working relationships based on trust and common interests, problems caused by defective parts would not have reached such proportions. A firm that works closely with suppliers by encouraging innovation and sustaining quality improvement processes can expect fewer problems during the life of the agreement.

An example illustrating the role of negotiating intangibles took place recently between Avis and Zip car.3 Avis agreed to acquire Zipcar for $12.95 per share in cash, a 49 percent premium over the closing price on 31 December 2012. For both companies, the negotiated agreement brought access to each other’s intangible assets. By purchasing Zipcar, Avis obtained an immediate entry into the growing market of car sharing, a list of 760,000 customers, a brand identity, a proven business model, a modern reservation system, and rights to parking spaces in selected locations. As far as Zipcar is concerned, it obtained Avis’ large fleet of diverse brands, increased utilization of its cars, access to airport locations, and an international network of customers.4 As car rental and car sharing is partially complementary rather than competitive, the transaction could prove to be a strategic decision provided Avis maintains Zipcar corporate culture and business model. Recent mergers and acquisitions show differences between reality and expectations on the part of the negotiators, where decisions are not made solely on facts but on potential intangible benefits.

It is no secret that negotiating profitable and sustainable business deals require a thorough understanding of each party’s needs and an accurate knowledge of the context in which the discussions are taking place. To do so, negotiators explore tangibles as well as intangibles. In a globalized economy, where e-commerce is revolutionizing business practices, intangibles are becoming essential for enterprises to remain competitive. By developing an appropriate mix between tangibles and intangibles, global-minded negotiators are able to optimize outcomes by expanding the fixed pie through creative solutions.