Overcoming the Gender Divide in Global Negotiation

A woman with a voice is by definition a strong woman.

—Melinda Gates

Traditionally, it has been held that when men and women negotiate against one another, men derive a better deal. It is because women tend to be more intuitive, people oriented, and patient, while men are aggressive, assertive, and dominant. But these stereotype notions may not be true when you see highly qualified women in positions of authority in the modern world. Although they may project a picture of acceptance, giving, and empathy, when it comes to negotiating, they can be tough and aggressive. It all depends on how one prepares ahead of time to negotiate. As has been said, “Chance favors the prepared mind.” Women who prepare themselves will fare better in negotiation than those who don’t.

The Gender Divide

There are six main differences that distinguish women from men negotiators: (1) Women want to feel and empathize but men want to prioritize, (2) women want to talk about problems before solving them while men go directly looking for solutions, (3) women notice subtleties among people better than men, (4) women say what they feel and move on to other matters while men tend to hold on to their emotions longer, (5) women feel bad when they are not liked but men feel bad when they don’t solve problems, and (6) men and women have different body languages.1

Generally, women have different negotiating styles from men—mainly in displaying patience, listening carefully, seeking everyone’s opinions, and trying to build consensus with the other parties. By showing interest in other people and focusing on the relationship, a team consisting of men and women executives may have a competitive advantage when negotiating in relationship-oriented cultures. Moreover, women have been found to be less receptive to unethical or deceptive tactics than men.2

When comparing the different characteristics of women and men negotiators, men tend to do better at the cost of long-term benefits and lasting relationship.3 Competitive strategies and adversarial tactics are more suited for one time transactions. For long-term business deals and repeat business, cooperative strategies are more effective than competitive ones, which are more in line with women’s preferred negotiating styles.4 By using a “softer” approach, women negotiators should prove to be more successful as they view negotiations not just as a business activity but as an interpersonal transaction where relationship plays a crucial role.

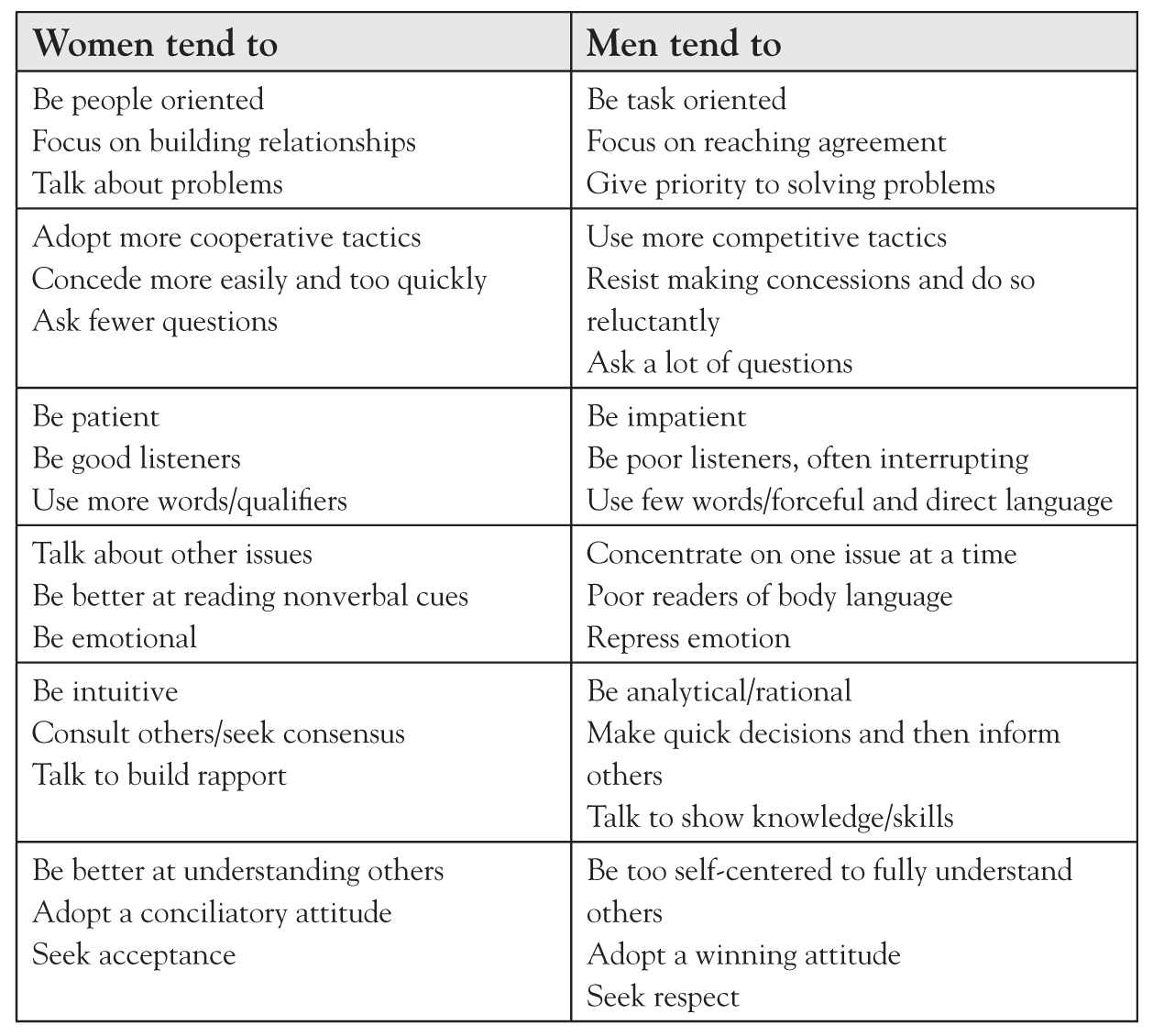

In other words, the key difference is due to the fact that women have dual roles when negotiating, one being issue-related and the other, relationship-related. By having two goals in mind, women are in a better position to apply collaborative strategies where success depends to a large extent on how the relationship dimension is handled. This assumes, however, that women negotiators know how to counter manipulative ploys, are willing to apply adversarial tactics when needed, are convincing in asking for concessions, and resist conceding too quickly. Figure 16.1 summarizes some of the key differences between men and women negotiators.

Figure 16.1 Major differences between men and women negotiators

The Cultural Divide

The above observations need to be somewhat modified when negotiating in cultures where the role of men and women are different and clearly defined. Hofstede identified five cultural dimensions common to all cultures with different intensity. These cultural categories consist of power distance, individualism versus collectivism, uncertainty avoidance, masculinity versus femininity, and short-term/long-term orientation.5 Masculinity pertains to societies in which men are supposed to be assertive and expected to seek material success. On the other hand, femininity refers to cultures where both men and women are supposed to be more modest and concerned with the quality of life. For example, masculinity cultures value self-assurance, independence, task orientation and self-achievement. Femininity cultures value cooperation, nurturing, service to others, relationships and consensus.

Negotiators from masculinity cultures are best suited for competitive strategies and adversarial tactics, which often leads to win-lose or lose-lose solutions. On the contrary, femininity cultures value cooperation, relationships, patience, and showing concern for the other party’s welfare. This favors collaborative strategies of the win–win type. In countries where women are not fully represented in executive positions, foreign women negotiators will be considered a foreigner first and will be less likely discriminated against than local women negotiators. Women negotiators doing business where gender equality is yet to be attained should emphasize their company’s importance, their position in the organization, and should display confidence. Furthermore, a personal introduction or a letter of support from senior management can help overcoming initial resistance from male negotiators.6

On the basis of his research, Hofstede classified 53 countries according to their masculinity culture. The countries with the highest index are Japan, followed by Austria, Venezuela, Italy, Switzerland, Mexico, Ireland, Jamaica, Great Britain, and Germany. Femininity cultures include Thailand, Portugal, Chile, Costa Rica, Denmark, Netherlands, Norway, and Sweden.

It is possible to group countries by languages. For instance, German-speaking countries (Austria, Germany, and Switzerland) are mainly masculinity cultures while English-speaking countries (Australia, Canada, Great Britain, Ireland, United States, and New Zealand) are moderately masculinity cultures. Latin countries (France, Spain, and some Spanish-speaking countries) are both masculinity and femininity cultures. Nordic countries (Denmark, Finland, Norway, and Sweden) and the Netherlands are mainly femininity cultures. That explains why many more women are in executive positions in the Nordic countries than elsewhere. Although not exhaustive, such a list is a valuable tool for preparing negotiations in these countries. It is also a fundamental indicator for selecting the team members and team leader.

The Corporate Culture

Corporate culture plays a growing role in business negotiation. Over time, most companies develop their own corporate culture with its corresponding set of values, rules, and policies. Knowing in advance companies policies concerning recruitment and promotion of women to executive positions will help both men and women negotiators identifying what the other side’s behavior is likely to be and develop appropriate strategies and tactics. For example, will the other party be led by a women executive or will the team consist of both men and women negotiators? If a company has no clear policy for the advancement of women employees and the negotiating team is all male, it is sending a strong message about its position about gender equality. As each negotiation is rather unique, it is critical to select team members who are both qualified technically and sensitive to cultural diversity, including gender differences.

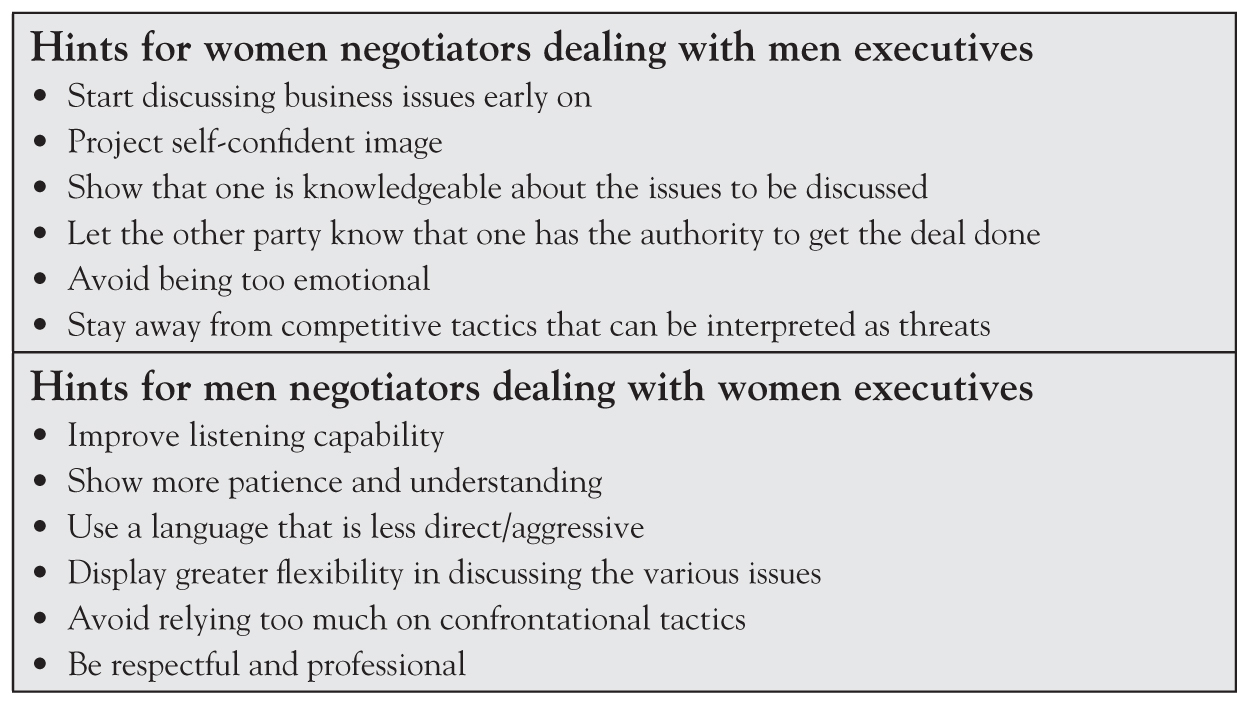

It is well known that preparing for a negotiation is a time consuming and difficult task, particularly in an international context. Successful cross-gender global negotiations are complex and challenging, and are becoming more common place than being the exception. To overcome being stereotyped, women should establish their credentials from the start and present their offers in a clear, brief, and direct language without introducing nonbusiness essential details that may confuse the other party.7 Figure 16.2 provides hints for negotiators to handle the gender divide.

Figure 16.2 Hints for cross-gender negotiations

Studies have shown that women place greater emphasis on relationships by talking about family or personal matters.8 This reflects the tendency to adopt a relationship negotiating style. Men, on the other hand, tend to prefer the competitive negotiating style. By doing so, they get straight to the point when negotiating

Getting Ready to Negotiate Across the Gender Divide

Dealing with cross-gender negotiations in an international context requires much more preparation than traditional ones. The key to success is to take the time to obtain the maximum information about the other party and to prepare accordingly. In addition, negotiators need to know the national and corporate cultures of the other party, company’s policy towards women equality, past negotiation behavioral style, composition of the team, and the overall context in which the negotiation will be taking place. Having collected this information, the strategy can then be developed, appropriate tactics identified, and team members selected on the basis of their technical and social competencies including gender sensitivity. If the other party is expected to include women executives in their team, it would be wise to appoint a women negotiator in one’s own team. In addition, male members should be briefed on cross-gender negotiations and, if time permits, mock sessions should be planned before meeting the other team. According to experienced executives, there is no such thing as an international business negotiation but only an interpersonal business negotiation, where both social and technical competencies are essential to reach optimum results.

Summary

Men negotiators operating in the global marketplace are increasingly interacting with women executives. As more women are moving into senior positions with negotiation responsibilities, overcoming the gender divide is critical for both men and women alike. Until recently, the literature on negotiation has largely ignored the characteristics of women negotiators. Recent research, however, shows that women negotiators can do as well as men if not better due to their ability to listen, read nonverbal signs, consult others, and adopt cooperative moves. As one of the most frequent obstacles in reaching an agreement is misunderstanding among the parties, women negotiators are ideally suited for addressing this problem by taking the time to understand people, discovering the other person’s underlying interests while establishing trust and credibility, and encouraging social harmony.