Interpretation is both an art and a science and to many a passion.

—Anonymous

Business executives negotiating with counterparts unable to speak the same language can count on the services of interpreters. Even if they have a working knowledge of the other party’s language, when it comes to negotiating international business deals, particularly complex ones, it is best to rely on professional interpreters to overcome the language divide. Too often, when cross-cultural business negotiations fail, the reason is frequently poor communications and misunderstanding among the parties. For instance, when Mr. Sato, Chairman of Toyota Motor Sales met Roger Smith, Chairman and CEO of General Motors, the language barrier made the visit “bewildering” in Smith’s words.1

The main distinction between the interpreter and the translator is oral versus written translation. Furthermore, translators have more time to refer to dictionaries and reference materials, and if need be consult language experts.2 Consequently, translators can revise their translation over and over again until they are satisfied with the end product before submitting it to the interested party. Language interpretation is much more difficult than language translation as it is highly demanding and stressful. The strain and tension is further aggravated as negotiation is itself a stressful process and even more so when negotiating in a highly global competitive environment.

Negotiators have the choice of simultaneous or consecutive translation. Generally, simultaneous interpretation is used in diplomacy, the United Nations and its specialized agencies, the European Commission as well as international and national conferences. Simultaneous translation demands language expertise, a high level of concentration and the ability to manage constant pressure throughout the discussions. In addition, it calls for special physical arrangements, sophisticated audio equipment, and technical support personnel, requiring significant financial investment, particularly if a second or third interpreter is needed. The other type consists of consecutive interpretation, which is more common in business negotiations. Concerning consecutive interpretation, negotiators have two options to choose from, either the short or long interpretation. The first option (short interpretation) is called “liaison interpreting.” Consecutive interpreting always refers to the long consecutive type of interpretation, with note taking. Consecutive interpretation actually means more than just providing a summary. The interpreter (unless the client wishes summaries) is required to reproduce the whole speech (with all the details). From the outset, negotiators have to decide with the interpreter what type of translation would be most suitable. As consecutive interpretation slows the negotiation process, and even more so if both parties exchange information through their respective interpreters, more time needs to be planned. On the other hand, it could be an advantage to slow down the discussions as negotiators have extra time to think about how to reply while the interpreter is translating the previous statement. This strategic advantage benefits both parties.

Interpretation Requirements

To avoid misunderstandings or misinterpretation, negotiators have to speak slowly and then pause after completing a phrase or statement to allow the interpreter to translate what has been said. It is important for interpreters to pay special attention to the negotiator’s speech pattern, voice variations, and pronunciation. In a number of languages, the interpreter has to rely on several words or sentences to convey the intended meaning. Because English is a more direct language, particularly in business, a statement in English will require at least 25 percent additional words to express the same message in French, Spanish, Russian, and many other languages as there are no specific equivalent words.

When negotiating with Japanese executives, interpretation is increasingly complex due to cultural factors and language structure. For example, when communicating with Japanese negotiators, interpreters have to overcome social factors and language syntax as well as handling periods of silence or lack of disagreement that can be mistaken for agreement. In addition, Japanese has several grammatical structures for communicating respect and power distance while English has only a few words for differentiating status.3 With regards to Chinese, the same words in English may have different interpretation when translated in Chinese, making translation even more difficult.4 In eastern Asian cultures, language tends to be indirect, where the message is communicated not only with words but with nonverbal cues and the social context. In Asia, silence is considered a part of communication, is highly appreciated, and long pauses between speakers expected. For instance, Japanese have a high tolerance for silence.5 In these cultures, communication tends to favor politeness, cooperative, and conciliatory behaviors. In Anglo-Saxon cultures where communications are direct, negotiators tend to adopt more competitive behavior and favor persuasion and arguments. As it may take more words and time for interpreters to translate, negotiators should not become impatient or assume that the interpreters are deviating from the original statement. This is particularly relevant when negotiations take place in cultures where time is considered a precious commodity that should not be wasted.

Interpreters’ Qualifications

Interpreters not only know how to listen but to understand what is being said and find the right words in another language. When negotiating with the help of interpreters, the negotiating parties should speak in short sentences, rely on plain words, and not interrupt. Lastly, when a negotiator speaks, he or she should address the other party, not the interpreter, particularly in traditional and relationship-oriented cultures as this could be interpreted as a lack of respect to the other negotiator. Moreover, there is a tendency to speak to the person sitting on the opposite side of the table who is fluent in your language, thereby ignoring the other team members including even the team leader, which in many cultures is considered disrespectful.6

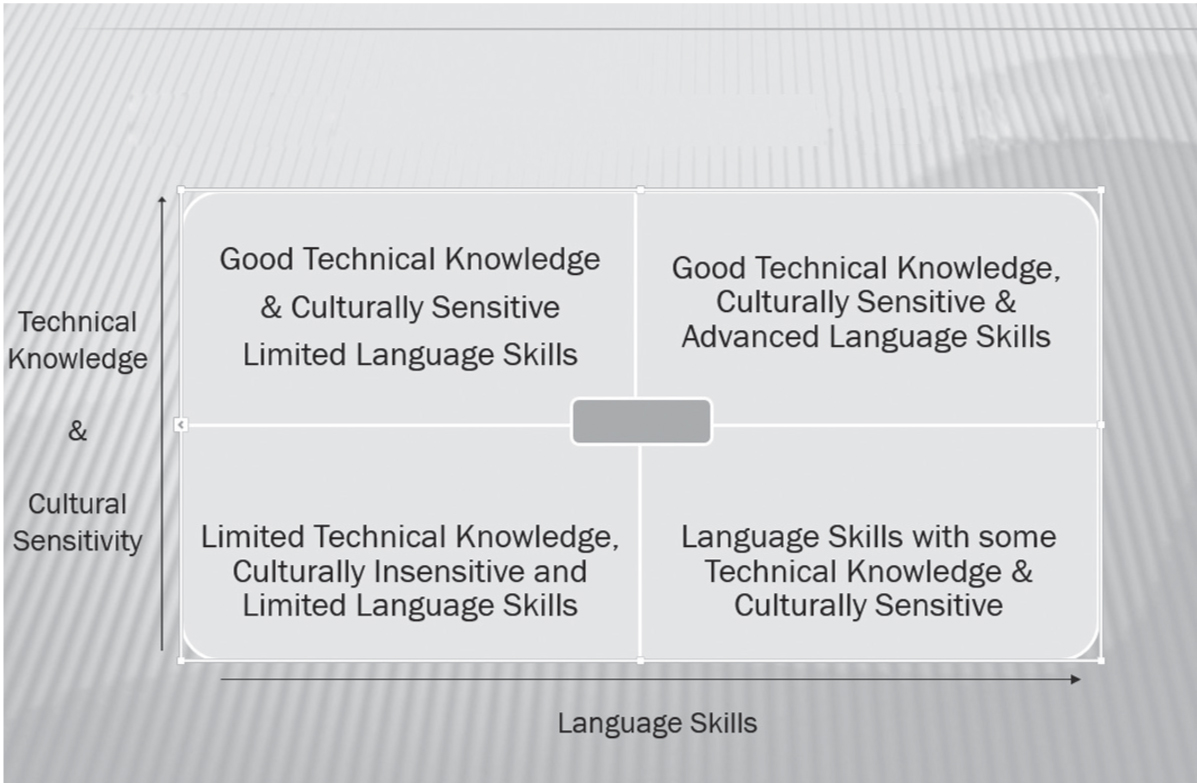

When hiring interpreters, negotiators need to determine their competencies and experience from independent and reliable sources. This is best done by contacting the embassy/consulate for their advice as they are likely to maintain a list of approved interpreters. Chambers of commerce, trade associations, or multinational banks are also excellent contacts for identifying professional interpreters.7 Ideally, the interpreter should have travelled frequently to the host country to remain up to date with the latest economic realities, political changes, and social developments. Although negotiators have access to a large pool of people with language skills, qualified interpreters are in short supply. To avoid unpleasant surprises, it is advisable to stay away from inexperienced interpreters, particularly when negotiating complex or sensitive business deals. Whenever possible, hire interpreters familiar with the other party’s culture and industry as well as ongoing business practices, as illustrated in Figure 18.1.

Figure 18.1 Technical, cultural, and language expertise matrix

If you have a large pool of interpreters to choose from, avoid those with high pitched, hoarse, stressful, or monotone voices. To have access to experienced interpreters, they should be contacted early on to ensure their availability instead of waiting till the last minute.

Involving Interpreters

Before the discussions actually begin, negotiators ought to hold one or more briefings with the interpreter to explain the nature of the deal, what you want in the way of translation, and why you want it. For example, make your requirements clear if you want everything to be translated or if you would rather have summaries. At times, your choice will depend on whether the negotiations are mainly technical and without major problems as both parties are near agreement, or difficult and require more time, plenty of patience, and persuasive arguments. To optimize the quality of their interpretation, brief the interpreters as early as possible about the upcoming negotiations, particularly the key issues that will be discussed, allowing them to consult background documents, carry out research to familiarize themselves with the issues to be negotiated, and the technical terms that are likely to be referred to. Advance preparation by interpreters is essential to the success of any business negotiation when the participating negotiators do not share a common language.

In the event you have prepared a written text to be read during the negotiations, make sure to provide an advance copy to the interpreter to familiarize himself or herself even if it is at the last moment, as it will be greatly appreciated. In relationship-oriented cultures, the interpreter’s input can go beyond interpretation by transmitting emotions, motivation, and speech variation of the negotiator. Actually, professional interpreters, independently of the culture, should take all these aspects into consideration. An experienced interpreter not only translates what the negotiator is saying but is able to adapt the verbal and nonverbal messages to the cultural context.8.Their role is to protect their own teams from confrontational conduct and even advise the team how to counter adversarial tactics.9

When negotiating with interpreters, it is better to speak clearly and pause after each statement to give the interpreter time to translate, whether it is liaison interpreting (short passages) or consecutive interpretation(longer passages). Each statement should be planned carefully so that it can be easily understood as well as ensuring that it does not contain abbreviations, slang, idioms, local expressions, double negatives, and words having several meanings. It is equally important to pronounce correctly the names of the party, places, dates, and figures. Moreover, avoid proverbs, sophisticated metaphors, and references to political events unless you are absolutely sure that it will not confuse or offend the other party. Special attention must be given to metaphors as they are culture oriented and can easily lead to misunderstanding and poor interpretation. Both interpreters and negotiators need to ask for clarifications, or repeat intricate or important statements when they have doubts about their meanings. As interpretation is difficult, stressful, and extremely tiring work, it is suggested that the interpreter be consulted for the judging the pace of discussions and planning breaks. To avoid mistakes by the interpreter, discussions should not go beyond a certain number of hours. Simultaneous interpretation of 30 minutes followed by 30 minutes breaks is the norm in most international conferences. In consecutive interpretation, more flexibility concerning breaks is possible, including the duration. For instance, a six-hour-day of interpretation is made up of frequent breaks and may require a second interpreter.

At times when negotiations near the deadline, there is a tendency for negotiators to speak faster and faster causing interpreters to fall behind in the translation and making unnecessary mistakes. To avoid these types of situations, negotiators can ask for more time to close the deal. However, they need to consult the interpreters to determine whether they are physically able to continue.

Interpreters as Facilitators/Mediators

There are times when interpretation is not really needed, but one or both sides insist on interpreters for reasons other than language translation, usually when anticipating highly emotional/conflicting situations or contentious/toxic issues, or to gain more time in preparing their responses. On other occasions, the interpreter is expected to play a role of go between or to act as a facilitator/mediator. For example, some time ago, one of the authors was assigned to accompany a trade delegation of Asian exporters of essential oils to meet French importers in Paris. His role was to do the interpretation from French into English as the French buyers were reluctant to negotiate in English. At the beginning of the discussions, he was doing the interpretation for both sides but found it increasingly difficult to do so as each side started to accuse the other of unfair business practices. As the discussions were getting more confrontational, he tried to interpret what was being said in a more neutral tone and less conflicting language. This approach did not help as the French importers without waiting for the interpretation started to reply directly to the accusations in English. From then on, he became a spectator rather than an interpreter, and finally a mediator. According to the Asian exporters, they were being paid low prices for their products. To them, low prices called for low quality essential oils. On the other hand, the French buyers were paying high prices as they needed fine quality ingredients for producing perfumes. The problem came from agents who profited from the situation by promising the importers quality oils while buying a mixture of various qualities at bottom prices, which created problems in the production of high priced perfumes. In the end, both exporters and importers realized the nature of the problem and came to the conclusion that it was best for them to deal directly, bypassing intermediaries.

Considering Interpreters as Team Members

To benefit fully from the interpreters’ expertise, negotiators need to get to know the interpreters. Besides holding briefings concerning the upcoming discussions, it is most helpful to share common interests and experiences to build a working relationship and develop trust. In case the negotiator is accompanied by one or more experts, the interpreter should meet the other team members as well. During the discussions, it is most likely that these team members will be called upon to express their views, making it essential for the interpreter to become familiar with their speech patterns, enunciation, and technical terms. These briefings are necessary if one wants to integrate the interpreter in the negotiating team. By considering himself or herself a part of the team, the interpreter may provide additional useful information about the other party and the cultural context. However, make sure that the interpreter does not get involved in the negotiations and remains neutral.

In a negotiating team, it is advisable to include a member who can speak the language of the other party. This member can notice any discrepancies in the translation and eventually help the interpreter with technical issues. However, if during the negotiations such a person finds the interpretation is incorrect, he or she should avoid interrupting the interpreter, but instead, write a brief note clarifying the problem and giving it to the interpreter. In addition, the interpreter can help the team members with their requirements if travelling to a country where their language is not spoken widely. Generally, interpreters are not available outside official function as interpretation is demanding and exhausting. In the event the interpreter is available to join the team at its social functions, it can reinforce the team spirit and solidarity. It is worth remembering that interpretation is highly strenuous, requiring plenty of recovery time. Do not be surprised if the interpreter declines the invitation, unless his or her presence is needed and included in the contract. Whether the invitation is accepted or refused, it will be appreciated a lot by the interpreter.

Language Knowledge

That a negotiator or a team member is conversant in the other party’s language should be mentioned before the discussions begin. If you do not want to do it in a formal way, you can have your bilingual team member say a few words in the host language at the beginning of the discussions. Withholding this information from the other party may be considered unethical and can lead to suspicion, a lack of trust, or even a break in the negotiations. For example, a North American consulting firm went to the Middle East to present a project for constructing a hospital. One of the engineers was fluent in Arabic having lived in the region as a teenager. Although the discussions were carried out in English, the local representatives spoke among themselves in Arabic in side conversations. This happens often as team members switch to their native language as they find it easier and more convenient to discuss issues among themselves. Furthermore, they may believe that the foreigners do not understand their language. During these conversations, information concerning weaknesses of the project was picked up by the visiting team thanks to its own Arabic speaker. As a result of this new information, the consulting firm presented a modified design that included most of their objections which allowed the discussions to move forward. To avoid any loss of face or embarrassment by the other party, the bilingual team member was excluded from further discussions in case the other party found out that their conversations were being listened to without their knowledge.

In the event you intend to record the negotiations, your request should be made as soon as possible, even before meeting the other party. The interpreter must also be asked if he or she agrees to be recorded. It helps if your request is supported with valid justification. If the request is refused, it is better to drop it as it may lead to suspicion or jeopardize the discussions.

Whenever possible, negotiators making an effort to acquire some basic vocabulary of the host language can help develop a friendly working relationship. Being able to speak a few words in the host language even with a foreign accent can break the ice. However, it is not recommended to inject words from a third language as it may lead to confusion. By letting the other parties know that you are trying to learn their language is not only a sign of respect for their culture but a commitment to the negotiations. By learning a language, negotiators not only acquire linguistic skills, but equally important, are gaining a better understanding of the other party’s behavior and thinking process, as there is a close link between language and culture. An excellent example of how language has an influential role in discussions is that of the discussions between Renault, the French automobile manufacturer, and Nissan of Japan. In early 1999, during the identification of possible synergies, Renault’s executive vice president Carlos Ghosn and 50 Renault researchers began to take daily Japanese classes to improve their understanding of Japanese culture and language.10 After 18 months of discussions, the negotiators agreed to an alliance that has proved to be mutually beneficial for both parties.

Summary

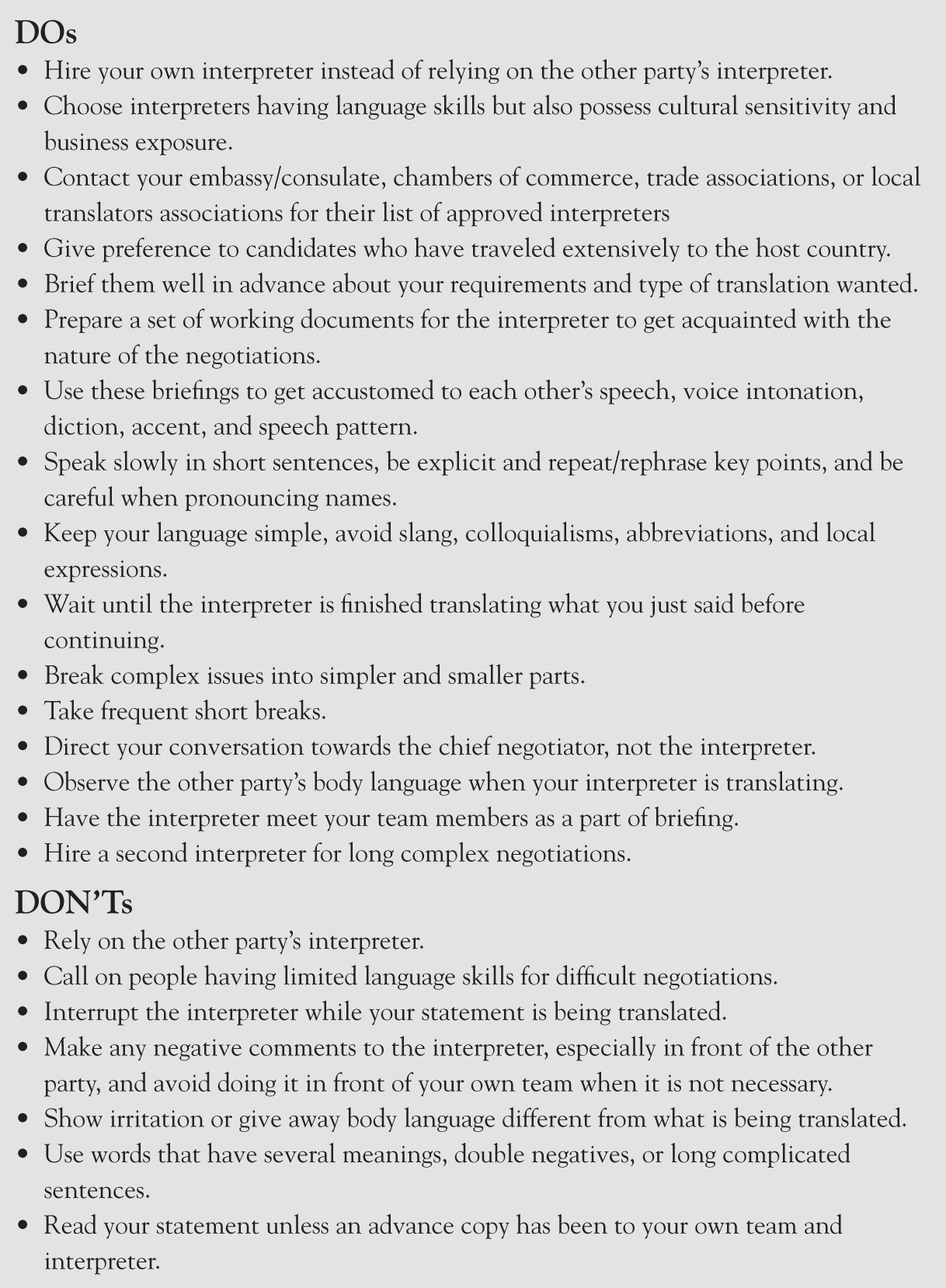

Effective communication is at the heart of any negotiation, particularly in cross-cultural ones. Communication between negotiators becomes more complicated when they belong to different cultures and do not speak each others’ language. Although English has become the lingua franca of business, not all negotiators have a proficiency level sufficient to negotiate it. In view of the rapid expansion of global trade, business executives will be increasingly dealing with foreign counterparts. To overcome the language barrier, negotiators can rely on professional interpreters to communicate and interact with their foreign counterparts.11 Negotiators can optimize the interpreter’s expertise by referring to best practices for interpretation as listed in Figure 18.2.

Figure 18.2 Best practices for negotiators relying on interpretation