7

A System that is the Victim of its own Success or an Anomaly that should be Remedied?

Ever since the 1980s, the trend towards the strengthening of intellectual property regimes has resulted in this respect in a very significant increase in the volumes of activity and the sums involved. What may be perceived as an overall inflationist trend is taking shape globally in different ways, not only through an intensification in terms of trademarks, industrial design rights, copyright, counterfeiting and piracy, but also through a proliferation of patents. This development both saturates patent offices and raises questions about the quality of patents and their specific outlines. This quantitative explosion, besides straining courts, also concerns the number of disputes among companies as well as the amount of damages awarded. It raises the issue of a need for balance, and recent reforms finally started to address this problem, especially in the United States, at the beginning of the decade.

7.1. The escalation of trademarks, industrial design rights, copyright, counterfeiting and piracy

The consolidation of intellectual property rights may specifically be presented as a necessary response to the growing problems of counterfeiting – as a violation of trademark, industrial design right or patent law – and piracy – in terms of copyright and neighboring rights. It is true that this phenomenon is developing very fast, strengthened by the emergence of online shopping in particular. Its range is hard to assess, especially since the available official figures are mostly limited to the products confiscated at borders. If we consider only its international share, the amount of counterfeit or pirated goods traded has been estimated at 200 billion dollars in 2008 and 461 billion dollars in 2013, namely the equivalent of 1.8% and 2.5% respectively of global trade for those two years and an average yearly 18% increase according to a joint assessment of the European Union Intellectual Property Office’s (EUIPO) and of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). The problem is particularly significant in the European Union (EU), where counterfeit or pirated goods represented close to 5% of the total value of imports in 2013 [OCD 16]. Based on the same estimation, but adding not only the trade value of counterfeit goods within the different countries but also the value of the goods pirated digitally in the cinema, music and software industry, an estimate has been made at the request of the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC) and the International Trademark Association (INTA). According to this, the total sales of counterfeit or pirated goods hovered between 923 and 1,113 billion dollars in 2013 and is predicted to be ranging from 1,900 to 2,810 billion dollars in 2022. This estimate confirms that China is by far the main country of origin of counterfeit or pirated goods [FRO 17].

The pace of trademark applications is not far behind this surge in counterfeit goods. The WIPO estimates that 5.98 billion trademarks were registered all over the world in 2015, which corresponds not only to an increase of more than 15% in relation to 2014 – and the highest since 2000 – but also to double the figure obtained in 2000. Since 2010, trademarks registered in China have on their own represented between 50% and 85% of the overall global increase. Although the global level of registered trademarks stopped growing in the mid-1980s, the number of registrations in China took off in the 1990s and has been greater than the number of patents filed at the USPTO since 2001. Even the latter, however, have doubled over the last 20 years. Recently, the annual number of trademark filings has also significantly increased in India, where it went from less than 100,000 for the period up to 2006 to close to 300,000 today [WIP 16].

Besides the development of trademarks deriving from large developed or developing countries, other reasons may account for how registered trademarks have increased to this extent in the last few years. In relation to this topic, [GRE 10] mention an increase in innovation, an extension in the types of trademarks allowable (colors, smells, music, shapes), a shift of the economy towards sectors – in particular services – characterized by a growing use of trademarks, or a possible change in how fashion is managed, resulting in the registration of a growing number of existing trademarks. The respective contribution of each of these factors is hard to assess and the relevant empirical studies are fairly rare. Besides this overall trend, the development of trademarks filings is characterized by greater volatility than the evolution of patents applications. This is due to how product innovation and marketing activity largely depend on the economic conditions, whereas inventiveness is steadier over time.

As for industrial design rights, the statistics provided by the WIPO indicate that the total number of applications filed worldwide reached 872,800 in 2015, a figure that is three times higher than the one obtained at the beginning of the 2000s. Once again, the recent developments can be explained mostly in relation to China, which accounts for around two thirds of the global number of applications observed since 2010, whereas the State Intellectual Property Office of China (SIPO) only started registering industrial design rights in 1985 [WIP 16].

7.2. A multiplication of patents of mixed quality and occasionally with vague outlines

The increase in patent filings all over the world seems equally to be in full swing. The figures provided by the WIPO prove this point. According to this source, the number of patent filings on a global scale rose to 2.9 million in 2015, increasing by 7.5% in relation to the previous year. While it was less than a million until the mid-1990s, it nearly tripled in 20 years [WIP 16]. This data corresponds in part to the international applications made according to the aforementioned PCT procedure and involving a request for instructions designating at least one of the 142 countries signatory to the treaty (PCT national phase entries), but also and essentially to the patent applications filed directly at the offices of a country or group of countries (for example, the EPO). These direct filings are biased, since the residents of the country or group of countries considered are generally overrepresented.

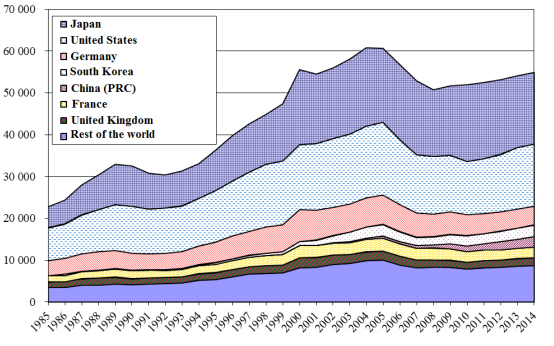

To avoid this domestic bias, it is common practice to consider the data related to the so-called “triadic” patents, which correspond to patents filed not only in Europe (at the EPO) but also in the United States and Japan. As these triadic patents are ipso facto relatively costly, considering them means eliminating a priori patents with low economic potential, so that patent figures can then be somewhat “lessened” in global terms. This is why data concerning triadic patents is generally considered as a good indicator for international comparisons. It follows that 84% of all triadic patents correspond to innovations made in the seven main countries included in the ranking (Figure 7.1), which remains dominated by Japan and the United States. In 2014, Germany and France occupied the third and sixth position respectively, with respective global shares of around 9% and 4.5% which roughly represent their respective global shares in terms of domestic R&D spending, whereas Korea and China are now taking fourth and fifth place. China’s share is still relatively modest and corresponded to 4.7% in 2014, but it is increasing very significantly compared with previous years.

To complete this overview, always based on the OECD database, it is also useful to refer to another indicator usually employed for international comparisons which is the patents filed via the international process called PCT, and once again considering the inventors’ addresses rather than the applicants’. From this perspective, we can see a high degree of geographical concentration as the seven main countries included in the classification represented slightly more than 81% of the global total in 2013. These are the same seven countries considered for triadic patents, but the hierarchy is somewhat different and includes, in decreasing order, the United States, Japan, China, Germany, South Korea, France and the United Kingdom. As for the global shares, the country that strikes us is once again China, whose share in PCT patents rose from 1% in 2002 to nearly 11% in 2013.

Figure 7.1. The development of the number of triadic patent families (1985–2014)1. For a color version of this figure, see www.iste.co.uk/lallement/property.zip

Naturally, not all patents are equal. Always in relation to the patents filed under the PCT, but this time with adjusted data that takes into consideration the quality of patents as assessed by the number of citations included in search reports, China slides down from third to fifth place in the global rankings [BOI 16].

Still, the development of Chinese patents is in full swing. Regardless of the location of the inventors and uniquely in relation to patent applicants, Huawei Technologies and ZTE, Chinese manufacturers of telecommunications equipment, were respectively the first and third global largest companies filing for patents via the PCT route in 2015. These positions were by no means usurped, as these two companies have been devoting more than 10% of their revenues to R&D for several years. With 359,316 patents granted in 2015, an increase of 54% in a year, the Chinese Office (SIPO) has for the first time overtaken the American Office (USPTO), which was left far behind with “only” 298,407 patents granted, all types of holders (residents or non-residents) being considered [WIP 16].

Is this increase in the number of patent applications proportional to the R&D effort? On a global scale, the data presented by the WIPO indicates that the growth in the number of patents filed is globally very close to the development of R&D spending for the period between 1995 and 2012. In any case, this is true if we take into consideration only first patent filings and discard subsequent patents, which correspond solely to the extension of previous patents to foreign countries. However, this overall structure hides wide differences in relation to the countries. If we consider China, the increase in the number of patent filings has largely exceeded that of R&D spending. In the rest of the world, especially in the United States and Germany, the opposite is true. In Japan, the significant decrease in the number of patents filed recorded from 2000 onwards is quite out of step with the steady upward trend of R&D spending. In France, the development of R&D spending and the increase in the number of patent filings, if not relatively parallel, have not differed much for the period between 1995 and 2012. Besides, we should not give too much weight to the potential differences between the increasing number of patent filings and the development of R&D spending, as the former may be evidence of changes in patent filing strategies that are completely unrelated to the productivity of the R&D effort [WIP 15].

De facto, the increase in the number of patent filings observed over the last few decades does not only show more effort in terms of R&D and invention. It is also due to the fact – which has been analyzed previously – that companies have profoundly changed and systematized their way of managing intellectual property. We should add to this the series of aforementioned changes in the institutional framework, especially in the United States: extension of the scope of patentability to include domains like biotechnology and software, courts that have become more favorable towards patent holders, greater involvement of universities in issues of intellectual property, etc. Moreover, globalization has modified patenting strategies by increasingly encouraging inventors to protect themselves abroad, as is shown by the booming development of patents filed via the PCT route managed by the WIPO. Apart from this specific type of patenting, more than half of the filed patents listed by the WIPO are not first patents corresponding to new inventions but subsequent patents; requests to extend patents to foreign countries [WIP 11].

Since the beginning of the 1980s, as is shown by the EPO, this wave of patents has been supplemented by the increased complexity of patent applications, which involves in particular a significant growth not only in the average number of claims per patent but also in the yearly average number of pages included in the patents filed. While the workload of the patent office considered has increased so significantly, the number of patent examiners has barely kept up. Similar problems have also arisen at the USPTO and the Japanese Office. This results in a congestion problem for the three offices, which involves a more significant backlog of pending patent applications and longer processing times for these applications. Naturally, the increased pressure on patent offices, and in particular on their examination process, has not been the same in every case [GUE 07]. Taking into consideration the average number of claims per patent, the number of patent applications that must be processed by each reviewer was, in 2008, two to three times higher at the USPTO than at the EPO, while the Japanese Office was in an intermediate position [POT 11].

In this context, the multiplication of patent applications seems to have taken place in part to the detriment of the quality of the patents granted, at least in the United States. In this specific case, quality degradation means overall relaxation of patentability requirements. In the United States, some patents have been granted for inventions that do not meet the novelty and inventiveness criteria, in particular in emerging domains such as software. Another piece of evidence used to assess the quality of the patents granted by different patent offices is the patent grant ratio, which divides the number of patents granted by the number of patent applications and hence represents an indicator of selectivity. It seems that between 1982 and 1998, for the same set of patents filed both at the USPTO and the EPO, the grand rate of applications was nearly 30% higher for the American office (a rate hovering between 80% and 90%) than its European counterpart (rate ranging between 50% and 60%), suggesting that the requirements for the grant of patents were stricter in Europe than in the United States [OCD 04]. Therefore, several elements show that the examination process is in practice less rigorous in the United States than Japan, and even more in comparison with Europe. We should also add that on the other side of the Atlantic the costs incurred by filing patents and patent search (concerning “prior art”) are lower and the scope of patentability is less limited. Over the last few decades, all these factors managed to increase both the propensity to patent and the grant of patents that were occasionally of dubious quality, that is patents not worth being granted [POT 11]. Granting bad-quality patents entails the risk of distorting competition and inhibiting innovation [FTC 03].

Besides, according to Bessen and Meurer [BES 08], these qualityrelated problems are more basically associated with the fact that the outlines of patents are often blurry. Taking into consideration that a property system is only effective if it indicates to non-owners the boundaries of the property considered, patents as property elements must normally perform a notice function; giving third parties precise indications about the area protected. According to these two authors, this notice function breaks down, and it has in any case deteriorated, in the United States in particular. This degradation itself is ascribed to a series of changes that have taken place in this domain since the mid-1990s, especially in relation to how courts interpret patent claims. It has resulted in patents written too vaguely and abstractly, including claims whose scope is vague or, for strategic purposes, somewhat concealed.

7.3. Increased pressure on the judicial system

In terms of intellectual property, the questions related to the judicial system, and courts in particular, obviously play a central role. [BES 08] recall them in their own way: the economic effectiveness of a property rights system depends to a very large extent on how these rights are enforced. According to them, the fact that the outlines of patents are hidden, unclear or unpredictable entails a serious risk of unwillingly infringing the patents of third parties. The core of these expensive disputes would correspond to inadvertent infringement.

An aggravating factor that dates back to the 1980s is that companies and public research organizations tend to adopt aggressive patenting practices, at least in the United States [COH 03]. Several analyses focusing on the United States, therefore, highlight the existence of a logic of one-upmanship and an arms race within the intellectual property system. Is there any way such trends could not lead to the exacerbation of tensions and the increase of disputes?

7.3.1. Patent-related disputes: frequency and costs that vary according to the sectors

To make an assessment, the simplest thing is to consider first the annual number of judicial proceedings over the last few decades. Between 1990 and 2006, this number has significantly increased in the United States for cases concerning patents, trademarks, and – especially at the end of this period and in relation to cases of online music file piracy – copyright. Only in relation to cases involving patents, this number has roughly tripled since the 1980s [BES 08]. Nevertheless, as Lanjouw and Schankerman [LAN 03] have shown, the number of disputes in the United States grew at the same pace as the number of patent filings in the period between 1978 and 1999. The litigation rate, the probability for the patent granted to be involved in a judicial proceeding, has remained relatively stable during the last two decades. This rate, which is equal to 1.9% overall, is quite low, but it varies widely according to the technology fields. Although it barely reaches 1.2% for chemical patents, it ranges between 2.5% and 3.5% in the domains of computers, biotechnologies and nondrug health. Another study shows that this rate is even higher for patents for software and business methods (Box 7.1).

Moreover, the risk of being involved in legal proceedings concerning cases that have to do with patents is substantially higher for small-size businesses and individual inventors than large companies, taking into consideration their respective number of patents. In the United States, naturally, the overwhelming majority of legal proceedings initiated for patent cases do not reach their conclusion: around 95% of them end in settlement agreements and, if appropriate, in most cases at the very beginning of the dispute. This means that a small part of the resources of the judicial system is ultimately devoted to this type of case. On the other hand, for the parties involved, the average cost associated with being involved in a lawsuit about a patent case considerably increased over the course of the 1990s [LAN 03].

For companies working in the semiconductor industry, the litigation rate in relation to R&D spending increased by 93% between 1973 and 1985 and in the period between 1986 and 2000. Ziedonis [ZIE 03] deduces that, ever since the mid-1980s, these companies have been spending a larger share of their budget for innovation on the protection of their own patents and disputes about the patents of third parties. According to [BES 08], the cost involved in defending oneself in patent litigation corresponds on average to at least 13% of the cost related to investments in R&D.

It is difficult to tell how much the average amount of damages awarded by courts in such disputes has increased over the last few decades. In Japan, the average sum of the compensation involved in intellectual property cases has increased since the end of the 1990s and is now much greater than the sum reported for France, despite being smaller than the current sum obtained in Germany. In the United States, legal costs have become exorbitant, especially due to a specific system: the role played by popular juries, the types of compensation for patent attorneys, etc. The one billion dollar mark has been attained or surpassed several times for damages awarded since the creation of the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (CAFC) in 1982 [CGP 06].

We can recall that in 1985, when the Kodak group marketed an instant photo process to the large public, Polaroid sued it and obtained, at the end of the legal proceeding, 967 million dollars in compensation as well as its withdrawal from the market. Let us mention another famous example. RIM (Research in Motion), a Canadian company mostly known for having produced Blackberry, a mobile phone, had to pay 612.5 million dollars to a company called NTP (New Technology Products) for infringing their patent rights at the end of a five-year-long dispute that ended with a settlement agreement in 2006 under the threat of an injunction that would have prevented RIM from accessing the American market. NTP, whose company headquarters are in Virginia, is specialized in patent licensing and does not produce itself any good or service implementing its patents. This emblematic example leads us to consider the role played by this type of actor, whose aggressive practices are often condemned.

7.3.2. The emergence of patent trolls

As for the legal practices concerning the management of intellectual property rights, the most striking phenomenon in the last ten years has been the clear emergence of what is conventionally called “patent assertion entities” (PAEs) or “patent monetization entities”. In this sense, the term “patent troll” is the one most commonly used, especially in the media and with a much more negative connotation, to define kinds of “patent evil spirits” defined by their ability to do harm [LAL 14a]. The related notion of “non-practicing entity” (NPE) is more neutral and it underlines that the bodies in question hold patents – after acquisitions or as the product of internal R&D activity – but do not themselves implement them.

In the United States, the FTC has recently devoted an important and long-awaited study to this topic, published in October 2016, where it defines “patent assertion entities” as companies that acquire patents from third parties and attempt to derive some profit from them by enforcing them against alleged counterfeiters either by negotiating license agreements, starting legal action, or both. In any case, the business model of these entities involves generating income from large patent portfolios by adopting a line of reasoning according to which – this is especially true for ICT – value does not lie in individual patents but in a combination of them, when they constitute a set of interconnected patents that form a system. According to a positive interpretation – which may be regarded as a euphemism – these entities lead to the “fluidification” of the patent market by driving a secondary market for patents that would remain unused without these entities [CHO 17]. In line with [BES 08], other experts have minimized their importance and think that mentioning patent trolls is partially a rhetorical flourish, claiming that these entities only represent a small part of the set of disputes over patents. The FTC’s study, however, clearly refutes this type of analysis, underlining rather the cost that these threats and legal proceedings now entail for society (Box 7.2).

Evidently, this phenomenon mainly concerns ICT and the issue of the patents related to software or computer-implemented inventions, especially in the United States. Undoubtedly it is partially dependent on the unique characteristics of the American legal system. Taking into consideration that digital technologies are spreading more and more to the rest of the economy, is the problem gradually spreading to other sectors and countries?

To make an assessment, it is useful to refer to the recent report of the European Commission on “patent assertion entities” (PAEs) in Europe [EE 16]. The report is based on the analysis of 32 cases of companies actively involved in this type of activity in Europe, out of which 16 are headquartered in North America and the other 16 are considered European. Ninety-two percent of the patent portfolio of these 32 entities is made of patents closely connected with ICT. The remaining 8% includes patents in fields like biotechnologies, life sciences, nanotechnologies, or the automotive industry. One of these 32 entities, IPCom (Munich), which is a German company, is at the head of a portfolio that includes around 160 patent families in the mobile phone industry and more than 1,000 patents in Europe, the United States, and Asia; it has initiated proceedings against groups like Nokia, HTC, T-Mobile and Apple at the Mannheim court. This report underlines that these entities, specialized in patent portfolio management, are occasionally also either “practicing” companies, which acquire patents from third parties and develop them through R&D activities, or shell companies set up by “practicing” firms (for example, Nokia and Ericsson) in order to enforce their patent rights. In Europe – just like in the United States, apparently – these entities present a wide variety of profiles and their various business models are hard to define empirically, all the more so as they evolve rapidly. Similarly, it is tricky to distinguish between their legal strategies and those traditionally adopted by companies that themselves implement their patents.

In any case, this report suggests that in Europe “patent assertion entities” tend to prefer starting proceedings related to patents that belong to technical norms (standards), which entails simpler and less expensive proceedings as there is no need to demonstrate that the rights of their patents have been infringed. The report also suggests that in Europe most legal proceedings initiated by PAEs are started in Germany. This is explained both by the size of the market of this country and the specific features of its judicial system (quality of judges, cost of proceedings, etc.). The report does not make any precise statements about the quality of the patents held by European PAEs, due to the lack of empirical data. However, it underlines that, once these patents are at the center of a legal proceeding in Europe, most of them are invalidated by courts. The report adds that there are also more “virtuous” PAEs whose activity differs from that of “pure” patent trolls and which carry out other activities besides patent assertion. Some offer advisory services to third parties in terms of intellectual property and carry out research aiming to more fully exploit the potential of existing technologies. Some have established forms of cooperation with university institutions or public bodies, while others are even financed with public funds [EE 16].

The last category includes, for example, the case of France Brevets, a public fund for patent investment and valorization, which was created in 2011 and whose core business consists of enforcing the patents of its constituents – SMBs or public laboratories – notably against powerful North-American and Asian industrial groups involved in electronics and telecommunications. France Brevets is therefore similar to patent sovereign funds like Intellectual Discovery in South Korea (since 2010), IP bank (since 2011), which belongs to the ITRI (Industrial Technology Research Institute), a Taiwanese quasi-governmental agency, or Japan’s Innovation Network Corporation (INCJ, since 2007), which essentially aim to defend the interests of said countries’ companies in particular against the attacks of foreign patent trolls [LAL 14a].

To recap, saying that the system of intellectual property rights is a victim of its own success is undoubtedly an understatement and even a mistruth. Arguably, the multiplication of titles (patents, trademarks, industrial design right, etc.) suggests that the entitled parties give overwhelming support to intellectual property tools. However, there are some significant matters of concern in many respects, as is shown by the great difficulty encountered by patent offices in staying on top of their workload and maintaining the quality of the examination procedure for patent applications or the significant increase in disputes, even in the field of copyright. Even though it is a cause for concern in itself, the emergence of patent trolls and other “patent assertion entities” is in turn only a symptom of a broader phenomenon which reveals the importance now attached to strategies based on the threat of legal action. Around fifteen years ago, Lévèque and Menière [LEV 03] were already drawing the conclusion that the reforms introduced since the 1980s have brought about a problematic situation of overprotection. Furthermore, the recent growth of counterfeiting on a global scale leads us to think that this overprotection is at least paradoxical, if not illusory. This reinforces the idea that intellectual property inflation, where it takes place, is not necessarily synonymous with the reinforcement of intellectual property, representing instead the symptom of both a drift and the conveyor of a dire malfunction.

7.4. A new reform movement from the United States: the backlash?

In response to the signs of this drift, the need for reform concerns first of all the American patent system. Developments in this direction or likely to take this path in the future, however, have a wider scope as they will certainly affect the rest of the world. In any case, the several criticisms directed at this system, such as it has developed since the 1980s, have led us to propose new approaches to improve it. Several key elements lead us to think that this reform movement started around ten years ago. As [BES 08] explained in their time, a reform like this had then become crucial, especially due to the specific problems related to software patents. According to these authors, the weight of some lobbies – especially patent lawyers and the pharmaceutical industry – makes it very difficult to carry out an effective reform. According to these two experts, substantially improving the American system is an all the more difficult task as it would imply the reform of institutions such as the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (CAFC) or the Patent Office (USPTO).

In the United States, after an unsuccessful attempt in 2007, a patent reform act still managed to be passed four years later. This was a major result as the reform introduced on September 16 2011 by the Leahy-Smith America Invents Act represents the most important revision of patent law in the United States since 1952. In the last 10 years or so, other major changes in case law have taken place. In this country just like elsewhere, the different changes made or the avenues for reform conceived to improve the intellectual property system – especially patents – fundamentally involve three broad areas.

7.4.1. Correcting the scope of patentability

The first type of reform involves the realm of patentable subject matter. In the United States, a line of thinking that has been significant for a long time favors a substantial extension of this field. However, in the last few years several legal rulings have ended up drawing the line after around 30 years of drifting, notably by narrowing the scope of patentability in critical fields such as business methods, software and biotechnologies.

Thus, American courts have limited the possibilities of patenting business methods and computer-implemented inventions, especially after the Bilski versus Kappos case. In this specific case and with a relevant judgment handed down in October 2010, the Supreme Court confirmed the judgment given by the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (CAFC) in 2008, which rejected a patent application for a method of hedging risks in commodities trading. In this sense, the Supreme Court did not exclude the principle itself of patenting business methods, but it considered the process claimed in this case as unrelated to a machine or device and unable to produce either a change of state or the transformation of a product (the so-called “machine-or-transformation” test). Some experts saw this is as the sign that American case law has timidly moved closer to the criterion in place in Europe, that is the “technical contribution to the prior art”. Others interpret it as the first significant breach in software patentability, at least in terms of computerized intellectual methods. More recently, another important decision given by the Supreme Court went in the same direction, this was the judgment handed down in June 2014 in the Alice versus CLS Bank case. It too should substantially re-orientate – towards more restriction – American case law in terms of patents for software or business methods.

In a certain way, [BES 08] predicted this development by writing that the status quo had become unbearable in the United States as it would have led to a sustained degradation of the patent system, imposed especially by the growing weight of the disputes related in particular to patents for software or used in ICT. The reason behind this is that software has become a general-purpose technology commonly used in most sectors. Many software patents have been granted for several years to companies in quite different sectors, thus increasing the aforementioned risk of litigation.

As for computer-implemented inventions, in any case, the patentability norms in place in the United States have become stricter after the judgment handed down in 2014 in the Alice case. They have significantly moved in the direction of the European norms, which have remained relatively the same in the last few years, to the extent that, according to Strowel and Utku [STR 16], we can now hardly say that patentability requirements in this field are laxer in the United States than in Europe. However, there are still uncertain areas on both sides of the Atlantic in relation to the patentability of this type of invention. A recent document published by the National Industrial Property Institute (INPI in French) reaches a similar conclusion: the patentability of computer-implemented inventions actually has a wide scope in Europe, it has become narrower in the United States in relation to business methods after the Bilski and Alice case, but case law remains divided for all kinds of matters involving software [INP 15].

As for the patentability of genetic resources, as we have already pointed out in relation to the Myriad Genetics case (Box 5.1), the possibility of granting patents for gene sequences, which was made available in the 1980s, has long been extremely controversial, such that the historical turnaround of the Supreme Court begun in June 2013 represents an actual break. This judgment naturally still allows so-called complementary DNA, modified genes that are artificially produced in laboratories, to be patented, but it helps to put genomic DNA, natural genes, into the public domain. It may help us reconsider the issue of gene patentability in Europe, where the directive of 1998 on the legal protection of biotechnological inventions is also open to criticism [CAS 15].

The Supreme Court’s decision to exclude from patentability any product “of nature” such as genomic DNA or any “law of nature” like a method used to calibrate the proper dosage of a specific drug may also raise problems for nanotechnologies, as several nanomaterials like graphene exist in nature [OUE 15]. Once again, there is still a certain dose of legal uncertainty.

7.4.2. Restoring the patent examination procedure and introducing a filter on copyright

The second main direction of the reforms started in the United States in the last few years regards first the organization of the examination procedure for patent applications. In this respect, the main change brought about by the Leahy-Smith Act of 2011 (“America Invents Act”) is that the United States has moved away from the principle of the first-to-invent right and adopted a first-to-file system similar to the one in place in Europe and Japan.

Another important aspect of this law concerns the – aforementioned – introduction of new post-grant opposition procedures. This step once again moves in the direction of the European system. A study on cloud-computing shows that these new possible types of opposition via the USPTO are already being employed in many situations [STR 16]. In any case, it is undoubtedly too early to assess the effects of the law of 2011 on patent quality. Even from this perspective, there are still several uncertainties.

Some academics wonder, for example, whether inventions in nanotechnologies meet certain common patentability criteria, in particular the novelty and the “inventive step” criteria, when the inventions considered are mere changes in scale in relation to preexisting technologies. In practice, these concerns about common patentability criteria do not seem (yet) to represent significant obstacles to the patentability of inventions in this field [OUE 15].

The types of reform put forward in the last ten years or so also include the idea that the examination procedure of patent applications should be made stricter in order to discard low-quality patents. It is exactly to this end that the EPO launched its “Raising the bar” initiative in 2010. Similarly, but this time in relation to computer-implemented inventions, one of the recommendations made to this end in a report published by the European Commission in 2008 is to make the knowledge disclosure requirement in patent applications stricter, or to filter applications with financial disincentives such as filing fees and the annual fees paid to maintain in force one’s rights [STR 16], in line with what [ENC 06] have suggested (see Box 3.1).

From a forward-looking perspective, reforms in the same directions have also been envisioned, this time in relation to copyright and neighboring rights. One of the paths considered currently involves reducing the term of copyright as an economic right, as is pointed out in a recent work focusing on the links between intellectual property and the digital transformation of the economy [INP 15]. Besides, some experts think that in this respect the entitled parties should no longer benefit from an automatic protection and that it may also be useful to rely on an official registry that can clearly identify the entitled parties. What these reforms share is the focus on two main objectives: on one hand, to expand the public domain to counterbalance the recent trend towards the extension of the scope and term of copyright, and on the other hand, to limit the transaction costs that a third party must theoretically incur if he or she decides to use certain works, taking into consideration the legal need to ask the entitled parties beforehand. At the very least, this reform would involve asking the authors to state if they claim all of their economic rights or only part of them. Thus, this step would essentially make benefiting from these rights conditional upon expressing the will to enforce them [CGP 06]. An even stricter option, which is especially mentioned in the case of the United States, involves introducing a registration procedure at the US Copyright Office, which would be very easy on an administrative level. From this point of view, [LES 01] also suggests that a work registered on these terms should benefit from a protection that lasts only five years but can be renewed 15 times, in return for the payment of a fee each time according to a progressive time-based schedule. This system involving renewal fees to maintain in force one’s rights would once again introduce a sort of filter that would encourage authors to keep their property rights for a long time only for works that they consider fully worthy.

7.4.3. Avoiding some excesses linked to disputes or blocking positions

The third main direction of the reforms started or proposed in the United States and in similar countries focuses on limiting the sources of costs and frictions linked to disputes or blocking positions. A debated approach involves the implementation of a form of litigation insurance. However, the relevant studies mentioned by [LAL 14a] and by [GRE 10] indicate that the insurance companies’ ability to offer polices at a reasonable price are limited in this field due to the classic difficulties encountered in risk assessment. They suggest that it seems wiser to systematize the mediation processes or to create a public mediation and advising service to solve litigation, like the patent mediation service offered by the British intellectual property office, in order to reduce the litigation cost, forestall disputes and consequently avoid saturating courthouses.

Other approaches, whether employed or envisioned, especially in Europe, involve the creation of new exemptions to make the system of intellectual property rights more inclusive and flexible. In the United States, similarly, the debate surrounding potential reforms occasionally mentions the consolidation of the research exemption [GAL 02]. Other measures involve improving how the technological knowledge market works by using compulsory licenses for patents linked to technical norms (standards) as a lever. However, as [ARO 16] point out, the reforms conceived for the patent system with the aim of facing the problems raised by “patent assertion entities” – sometimes called patent trolls – must avoid harming providers of specialized technologies such as independent inventors, academics and R&D consulting firms.

Apart from these three main directions, other types of reform are sometimes put forward. [GAL 02] mentions, for example, the possibility of introducing ad hoc regimes for some of these objects in order to introduce more differentiation in relation to the specific nature of the subject matters to protect. In this respect, the WIPO reminds us, however, of the case of the sui generis right established to protect semiconductors during the 1980s both on a national scale (in the United States in 1984, in Japan in 1985, in Europe with a directive in 1986) and internationally (in relation to the TRIPS agreement of 1994). This right protects the topography of semiconductors, i.e. the mask of integrated circuits, whereas the value of these chips lies more in their functionality. Besides, it is relatively easy to modify the mask of a chip without altering its functionality. Moreover, chip piracy has become virtually prohibitive, given their increasingly short lifecycles, high production costs, as well as customization requirements. For these reasons, this ad hoc right has overall barely been adopted by inventors and industrials in this sector, it has not been the cause of legal proceedings and therefore it has barely had an effect on the practices of this field, which have continued to rely mostly on patents. The WIPO uses this failure to conclude that public authorities, before any such reform, must try to anticipate this type of problem by considering the dynamic aspect of the technology in question [WIP 15].

Institutional development, technological change, and several other factors have thus brought about a multiplication of industrial property titles on a global scale just as counterfeiting and piracy phenomena are booming. In response to the detractors of the intellectual property system, who criticize in particular the growing stream of patents, other analyses try to play down the situation by showing that essentially there is barely any global discrepancy between patent trends and R&D developments. Besides, several significant changes over the last 10 years or so indicate that the patent system in place in the United States has begun a phase of reconsideration in order to correct a series of excesses which have emerged in the past thirty years. Consequently, the American system has moved in the direction of the European one in several respects.

However, several problems remain: difficulties encountered in containing counterfeiting and piracy, strategic behaviors of patent holders, strained offices and tribunals, etc. In the end, the reforms started in the last few years seem to be, in many respects, still insufficient for the recently observed level of tension and malfunction. An influential magazine has recently concluded that it is time not only to make the patent system less invasive but also to “repair” it [THE 15].