8

Overall Assessment and Conclusion

In terms of innovation, what are the global consequences of the developments analyzed in the last two chapters? To what extent does the system work properly? To make an assessment, we should go beyond the aforementioned works (Chapter 2) that analyzed the effectiveness of intellectual property rights in relation to innovation from a microeconomic perspective. We still need to consider the question of the consequences on innovation processes on the economy and society as a whole. The relevant analyses usually raise two key issues. On one hand, how and to what extent does intellectual property affect innovation and economic growth? On the other hand, what is the impact of patents as mediums for the dissemination of knowledge and, more generally, to what extent does intellectual property represent a key factor for the circulation of knowledge and technology transfer? To leave generalities aside and carry out a more precise analysis, it is in many respects necessary to tackle these issues from a sectorial perspective. This helps us see that, although intellectual property rights affect innovation practices, these practices in turn have an effect on these rights. These mutual interactions lead us to reason in systemic terms, considering intellectual property rights as a component of innovation systems. Finally, this attempt to provide an overall view encourages us to consider, in the name of innovation, if abolishing intellectual property rights is a pressing need, if we should maintain the current system unchanged, or if it is preferable to keep trying to reform it.

8.1. A possible lever for the countries’ economic growth through the incentive to innovate

The aforementioned empirical works show that intellectual property rights and patents in particular generally have a positive effect on the holders’ economic performances. This remark on a microeconomic level, however, does not necessarily apply to a broader context, whether meso- or macroeconomic. What about the consequences of patents on investments in innovation and as a lever for the promotion of economic growth, at the level of sectors or countries?

8.1.1. Some historical lessons

To make an assessment, it is first useful to deal with this topic from the perspective of economic history by going back to the first industrial revolution or considering more recent periods. Some works carried out on this topic allow us to consider the counterfactual issue: what would happen to innovation performances if the patent system did not exist?

Moser [MOS 05] provides a partial answer to this question by studying the inventions associated with the two universal expositions held in London in 1851 and in Philadelphia in 1876. Thus, she analyzes the development of patents in a certain number of countries according to whether they could count or not on patent laws at the time. She shows that in countries without patent laws inventors focused their efforts on fields where other forms of protection were available, especially where the protection provided by trade secrets was effective. This was the case for Switzerland, for example, which invested in the textile industry, the food industry and watchmaking at the time. In the United States, where the protection provided by patents was actually insured and relatively accessible in terms of costs, innovation focused on mechanical engineering. The Netherlands, which abolished their patent laws in 1869, later substantially increased their innovations in the food industry. Overall, this study suggests that these different forms of protection – among which patents – have had a significant effect on the sectorial direction of the innovation activity but not on its general volume.

During the first industrial revolution, according to [BES 08], few major inventions benefited substantially from patents in Great Britain – at least before the mid-19th Century – while this was more the case in the United States. In the same period, countries that lacked patents were as innovative as those that could rely on them. A good deal of the industrial development of Switzerland and the Netherlands indeed took shape in a period – the 19th Century – in which they had not instituted a patent system yet. However, as [MAC 58] points out, these countries managed to do so in part by imitation, thus profiting indirectly from technological innovations made in countries equipped with patent systems. We should be suspicious of some historical comparisons, which occasionally rely on the post hoc ergo propter hoc logical fallacy [MAC 50].

As for Japan, Granstrand [GRA 96, GRA 16] thinks that intellectual property has positively contributed to the development of the country’s innovation system ever since it adopted – in the Meiji era – a system of intellectual property rights that included a patent system. This is particularly true for the postwar period, which allowed the Japanese innovation system not only to catch up but also to reach the pole position, partly with the system of intellectual property rights and especially through the analysis of existing patents, licensing agreements, and the improvement of imported technologies thanks to a large number of small enhancements, most of which were patented.

Lerner [LER 09] zooms out by examining the effect of 177 legislative changes related to patent protection in 60 countries between 1850 and 1999. He draws the conclusion that reinforcing the protection provided by patents in a given country does not seem to entail a positive effect on the patents filed by its residents. On the other hand, the reinforcement of the patent system causes a sharp increase in the number of patents filed by non-residents. This increase in patents filed by non-residents could be explained by how foreign companies are encouraged to settle (FDI), even if this is only a hypothesis.

As for developing countries, the available studies highlight a mostly-negative relationship, which is negligible at most, between innovation and the protection provided by patents. This link significantly depends on the level of economic and industrial development of the country in question. Gamba [GAM 16] draws the conclusion that developing countries should adjust their system of intellectual property rights in a sensible and gradual manner.

Qian [QIA 07], as an example and to assess the specific effect of adopting a patent law on 26 countries with different levels of development, simulates a natural experiment by using a matching approach to compare these countries to a group of other countries with similar observable characteristics. She concludes that, for all the countries considered, the adoption of such a law on patents does not in and of itself help drive innovation, judging by the effects on the patents granted, domestic R&D spending and the exports of the pharmaceutical industry. She adds that the effect measured in this manner is, on the other hand, significant when the countries considered have a high level of development and education and enjoy a liberal economy.

Besides patents, other factors determine the ability of developing countries to profit from existing technologies and scientific results: social and institutional factors, various types of equipment and infrastructure, scientific and technological capabilities. In this respect, these countries’ ability to catch up on more advanced countries depends largely on factors other than intellectual property rights [CIM 08].

Other works focus less on the effects of intellectual property on innovation or economic growth than the consequences of the latter on the former. This is especially true for Park and Ginarte [PAR 97], whose study deals with a shorter period – from 1960 to 1990 – once again on 60 developed or developing countries. The study suggests that these countries have equipped themselves with systems of intellectual property rights that are all the more powerful as they present a significant R&D investment rate, at least for developed countries. The study deduces the existence of a threshold past which a country benefits from instituting a strong system of intellectual property rights. For the country considered, this threshold involves less the level of development in itself – in terms of GDP per capita – than the key factors for economic development, R&D potential and the degree of economic freedom and openness.

Finally, a small number of monographs focus on specific countries, in most cases the United States. As an example, ten years ago [BES 08] thought that for potential innovators in this country the risk of inadvertently infringing the rights of third parties had become such that, for listed companies and all sectors considered, it was doing more than counterbalancing the incentive component of patents, as it was by then globally discouraging the creation of new technologies. According to their estimates, it was around the end of the 1990s that the costs/advantages ratio for patents had become negative, providing concrete evidence that the patent system was broken-down, namely that it malfunctioned as a property system by failing to sufficiently provide clear and effective notice on the outlines of the rights conferred.

8.1.2. A diagnosis that remains contrasted and not sufficiently substantiated

Which general lessons can we draw from this kind of empirical work? Do intellectual property rights, and patents in particular, boost innovation and overall productivity gains? Although it is empirically an established fact that economic growth relies mostly on innovation and its dissemination, the empirical elements regarding the role of intellectual property rights are vaguer. There is no consensus on this question, which is as much debated as it is complex, as [GRE 10] and [ARO 08], underline. The difficulty encountered in trying to find an answer is partly due to how the composite indexes used to assess the force of intellectual property rights have their limitations. These synthetic indexes demonstrate the multifaceted nature of the rights in question, and yet they provide only a partial overview and discard other significant aspects, in particular in relation to the degree of enforcement of the rights.

As [COH 03] point out, there are also limitations in terms of available data, especially concerning the uses and consequences of patents, for example in relation to license agreements and the resulting fees. Admittedly, there is data on disputes about intellectual property from a legal perspective, but this kind of matter is settled outside of courts in most cases. Moreover, there is no data on situations – more frequent than legal action – in which patent holders send letters to third parties to notify them that they are infringing the rights of these patents and to ask them to settle the situation through license agreements. Furthermore, there is no estimate of the opportunity costs incurred in situations where specific innovative approaches may not be explored or extended under the patent holder’s threat of legal action. In other words, it is difficult to assess the dissuading effects of the threat of litigation on innovation, especially for biotechnologies [GAL 12]. As for the software industry, similarly, the arguments according to which intellectual property rights with imprecise outlines dissuade from investing in innovation have no empirical basis [LER 07]. For all these reasons, the economic analysis can barely understand the costs and benefits of litigation, just as it fails to precisely determine the advantages and drawbacks of license agreements. This is why on a general level there are still only relatively few empirical works on the effects of patents on innovation, or even on the more specific issue of their effects on the R&D activity.

8.2. A key factor for technology transfer and the dissemination of knowledge

To accurately answer the question about the consequences of the intellectual property system on innovation, it is not enough to consider the classic issue of the incentive to innovate. As [GAL 02] and [POT 11] point out, the effectiveness of a patent system must also be analyzed in relation to two other key issues. First of all, does the patent system help disseminate more knowledge? Secondly, does the patent system facilitate technology transfer and the development of the technological knowledge market?

8.2.1. Promoting technology transfer through transnational companies

Branstetter et al. [BRA 06], who studied the effects of the reinforcement of the protection provided by intellectual property rights in 16 countries over the period between 1982 and 1999, provide a – positive – answer to this question. The original nature of their approach involves analyzing whether or not this change entails consequences for the technology transfers between American multinationals and the subsidiaries they have set up in the countries considered. The study shows that reinforcing legal protection leads to an increase in the price incurred by the subsidiaries in question in using the intellectual property held by their respective parent companies, reflecting the value of the technology transfers performed. The existence of these transfers is also borne out by another effect on the subsidiaries of these American multinationals: an increase in R&D spending. Besides, like [BRA 06, LER 09] identify a positive effect on the patents filed by non-residents in the countries considered, but no effect on the patents filed by residents. Thus, this study does not establish that reinforcing intellectual property rights boosts innovation for “national” companies, but it shows that multinationals are sensitive to it and respond to it by increasing their technology transfers towards the countries considered, in return for substantial fees.

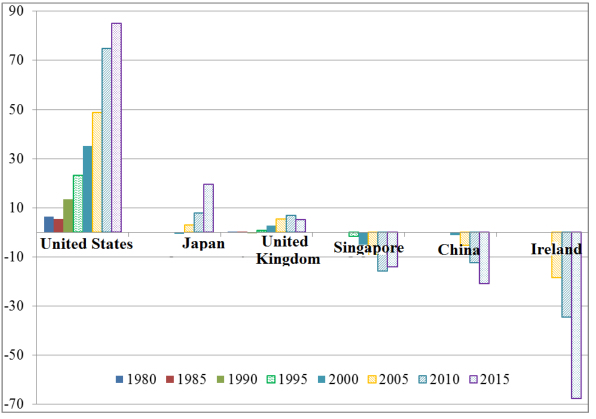

To gain some insight into the main countries for which intellectual property constitutes a significant net source of income or a net cost component, it is instructive to consider the flow of payments linked to intellectual property, based on the data about the current account balance. On a global scale, the fact that these flows have been growing more rapidly than the countries’ wealth – measured in terms of their GDP – especially since the 1990s aptly illustrates that the knowledge markets built on intellectual property are becoming more important [WIP 11]. This suggests that, apart from the United States, Japan, and some European countries that are reaping increasing rewards, most other countries are racking up deficits on this level (Figure 8.1). Besides, it seems that the overwhelming majority of the payments in question represent transactions carried out in an intragroup context, within transnational companies [LAL 10]. This also explains why a small number of countries concentrate a large part of the deficits in this respect. Some of these countries in deficit – mainly China – are globally trying to catch up from a technological perspective and they consequently represent net importers of intellectual property for the needs of their industries. Others – such as Ireland and Singapore – also play an important role as countries that welcome foreign multinationals but also – and even especially – due to a very appealing tax system that facilitates what are euphemistically called tax optimization practices through accounting systems that involve transfer pricing.

Figure 8.1. Balance between intellectual property income and payments (in billions of dollars at current prices) (Source: Balance of payments statistics of the International Monetary Fund, compiled by the World Bank). For a color version of this figure, see www.iste.co.uk/lallement/property.zip

These practices involving transfer prices allow transnational companies to attribute more or less benefits to their subsidiaries in a specific country according to how heavily the latter tax the income deriving from intellectual property assets (transfer of assets or fees resulting from licensing agreements). This is why several countries have implemented tax relief schemes for these types of income. The studies carried out on this topic show clearly that this kind of measure – called “patent box” – barely incentivizes innovation and is used mainly for tax attractiveness purposes [FMI 16].

However, intellectual property protection plays a significant part in helping us understand why transnational companies decide to locate their innovation activities in a specific country. Protecting intellectual property is thus considered as the second most important issue related to foreign R&D activities, after those concerning how to recruit and retain talents, according to a survey considering 207 large companies in 23 countries involved in R&D activities in more than 2,000 sites and distributed over more than 60 countries [PWC 15].

Besides the technology transfer performed through transnational companies, the issue also involves the contribution of intellectual property rights to the development of technological knowledge markets that has mainly taken place since the 1990s. These markets may make R&D more effective by bringing about a greater level of specialization between the actors concerned: companies, technical centers, public research laboratories. The available empirical elements indicate that this contribution is positive overall thanks to license agreements, which allow companies to negotiate with the entitled parties at a reasonable price [GRE 10, GUI 14].

8.2.2. A key tool for the regulation of knowledge flows

One of the main channels that allows knowledge to flow within innovation systems is the mobility of human resources. In this respect, intellectual property rights play an important role in terms of trade secrets involving non-competition clauses whereby individuals promise to a given company not to disclose the specialized and noncodified knowledge of the employer they are leaving to their future employer for a certain period of time. These clauses may involve technological knowledge as well as organizational know-how or professional practices. Thus, they may concern any kind of sector a priori, including services. For the three emerging technologies considered in the recent document published by the WIPO about disruptive innovation (nanotechnologies, robotics, and 3D printing), trade secrets are thought to be playing an increasingly significant role, since the mobility of “knowledge workers” has grown. Even though codified knowledge is readily available, its implementation always crucially depends on the human factor. As a result, this will represent a significant organizational issue in the future both for innovation and the dissemination of technological knowledge [WIP 15].

The issue of knowing the extent to which the patent system facilitates the dissemination of scientific and technological information leads us to consider the actual effectiveness and usefulness of the legal requirement to disclose knowledge through patents. Naturally, patent databases are increasingly large and they allow companies to find their bearings in relation to their rivals or partners thanks to ad hoc mapping elements. To give an idea of the scale of patent-information, it is often said that patents contain 80% of the scientific and technological information available. Nonetheless, some analysts – among whom [BES 08] – have doubts about the actual contribution of patents to the dissemination of technological information. They think that the information disclosed is in reality often inadequate or opaque, so that the invention considered cannot be reproduced [CIM 08]. They are skeptical about the researchers’ propensity to read patents, which are often regarded as essentially legal documents written by legal experts [WIP 15]. The case of nanotechnologies proves the point in a more nuanced way (Box 8.1).

In other sectors it is possible to find cases of more evident disclosure followed by more effects. For instance, the first patent filed by Bayer in 1932 for the manufacturing process of sulfa-based antibiotics disclosed a good deal of the information necessary to replicate this invention. Consequently, and also due to the fact that competitors later managed to “invent around”, the Bayer patents for this invention were devalued. Through this disclosure, patents then facilitated the cooperative processes between the academic and the business world, thanks to which semisynthetic penicillin could be produced quite rapidly. This series of innovations related to antibiotics spread across industrial countries fairly rapidly and at a low cost, supporting the idea that patents represented no obstacle. This wide dissemination was also facilitated by the fact that the patentability of these inventions was then only partial for process innovations (after the discoveries made by the Pasteur institute at the end of 1935 and Fleming’s discovery of penicillin a few years before) and nonexistent for product innovations [LES 07, WIP 15].

8.2.3. A key tool for the commercialisation of public research results

Finally, the tools involved in intellectual property rights play a central role in the valorisation of public research results. In this respect, the United States represents a significant point of reference after the Bayh-Dole Act of 1980, which created a uniform legal framework that authorized universities and research bodies to claim the property of the inventions made with federal funding. This strongly encouraged them to establish or develop skills in terms of patent filing, license agreements, the creation of startups, etc. At first sight, this type of law seems to present a major fault. Does patenting a publicly funded invention not mean limiting its use? Would it not be better if this type of invention were placed in the public domain to increase its use? In the United States, like elsewhere, this was what happened in most cases until the 1970s. Academic institutions did not concern themselves with the future of their inventions, adopting in most cases an approach that was open and rather in favor of an increase in competition. Companies, for their part and due to the impossibility of negotiating license agreements, whether exclusive or not, were reluctant to invest in launching the inventions in question on the market. Due to the lack of intellectual property rights, there is also the risk that these inventions are developed more easily abroad than in the countries where taxpayers have funded them. In relation to these points, the Bayh-Dole law was a significant game changer. It requires universities and research bodies that have benefited from federal funding to give licensing preference to small (American) businesses when they have to develop results.

This law has inspired comparable schemes in several other countries ever since. It is still leading to misunderstandings. In particular, it seems that the activities involving the development of public research results only rarely leads to major successes in terms of income received. In most cases – this is true both for the United States and the United Kingdom or Germany – these activities are not profitable in microeconomic terms. This is not a sign of ineffectiveness, but it reflects the fact that the inventions considered essentially benefit the companies that make use of them as well as other socio-economic actors (consumers, users, etc.). The ultimate goal of a properly understood policy of development is not financial and it involves increasing the overall economic consequences in the country in question, especially by improving the relationships between public research and companies [LAL 14b]. In this respect, another lesson drawn from international comparisons is that intellectual property should not become a source of tension or contention, drawing on the practices that have already proved effective especially abroad. Concerning this point, the cases analyzed by [OLL 13] can teach several valuable lessons, especially in relation to the Lausanne École Polytechnique Fédérale (EPFL) in Switzerland, the Technion – Israel Institute of Technology in Haifa, and the Fraunhofer institutes in Germany. In any case, the actors involved in public research – namely, universities and public research bodies – account for a growing percentage of all the patents fillings. At the EPO, this share reached 6% in 2016.

8.3. A joint evolution on a sectorial level as well

The empirical studies that focus on the relationships between intellectual property and innovation at an aggregated level lead to mixed results which are occasionally hard to interpret. This ambiguity figures prominently in the link between patents and innovation; it is largely due to the fact that the policy followed in terms of patents, the use of patents, and R&D activities all determine each other [ARO 08].

To assess these links, the most pertinent perspective perhaps involves less countries or groups of countries than sectors or technological domains. Always from this perspective, it seems that we should leave aside explanations in terms of univocal causality and consider how intellectual property and innovation determine each other.

8.3.1. The case of semiconductors and software

For the United States, this logic of co-evolution may be illustrated by two cases: the domain of computer-implemented inventions and the semiconductor industry. In these two specific cases, several studies based on corporate data have focused less on the analysis of the impact of intellectual property on R&D and innovation than the opposite study considering the factors that determine the development of patents.

As for the semiconductor industry, [HAL 01] conclude that the rapid growth in the number of patents filed in this country between 1979 and 1995 was largely due to a more aggressive patenting behavior adopted by large companies in the sector, in a context of intense patent races, leading the authors to hypothesize that companies in this sector tended over time to patent more marginal inventions. The two authors consider the creation of the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit as the main reason behind this increased propensity to patent. In this sector, in other terms, the patent reform started in the United States at the beginning of the 1980s has not necessarily led to an increase in the number of inventions and has only managed to strengthen the propensity to disclose these inventions by patenting them. However, this study has barely been able to confirm the hypothesis that the quality of patents is becoming worse, in light of the number of forward citations mentioned in patents.

In the semiconductor industry, according to the WIPO, follow-on innovation and its dissemination have overall been rather favored by the use of intellectual property rights, especially thanks to the role played by patents in favor of the investments in R&D, the actors’ specialization, and the funding of startups [WIP 15].

Computer-implemented inventions (“software patents”), according to the definition considered by [BES 07], represent 15% of the total yearly number of patents granted, only 5% of them belong to software publishers, and they are mostly either held by large companies in sectors belonging to the manufacturing industry (computer manufacturers, etc.), where they are used for strategic purposes. In this domain – just like in the semiconductor industry – the sharp increase in the propensity to patent is mostly unrelated to factors such as the development of investment in R&D. The increased patenting trend related to this type of invention derives to a large extent from the fact that changes in the legal framework have substantially lowered the cost incurred in obtaining patents in this sector, both lowering patentability requirements and making courts more likely to enforce these patents in case of litigation. Furthermore, the empirical elements highlighted by this study suggest that software patents replace the R&D effort in an industry, they go hand in hand with a less intense R&D activity.

However, this last result obtained by [BES 07] is refuted by [LER 07]. The latter agree that the changes in case law favorable to the patentability of “software patents” have led to an uncommon increase in patents filed in this sector. However, they think that the increased use of patents by software publishers in response to the reduction of the protection provided by copyright at the beginning of the 1990s has been accompanied by an increase in investments in R&D and turnover. Thus, they think that the change in the legal framework has had no negative consequences on this type of variable at a microeconomic scale. Yet, they admit that this result does not invalidate the possibility that the increased use of patents may bring about the creation of patent thickets that would overall reduce innovation in this sector.

8.3.2. Examples of past and present disruptive technologies

The recent document published by the WIPO on disruptive innovation provides some general lessons about the role played by intellectual property rights in this respect.

Four main points emerge when we consider first the 20th Century and the three following examples: aeronautics, antibiotics, and – once again – semiconductors. First of all, experience shows that intellectual property rights helped at least partially reap the benefits deriving from R&D activities, which is why they represented an incentive for innovation. Thus, innovators used these tools quite often to protect the results of their activities, heavily relying on them in the semiconductor industry. Secondly, the innovation ecosystems considered have been partly driven by explicit or implicit knowledge sharing arrangements that helped facilitate the development of new technologies and the marketing of further innovations. As for aeronautics, the initial logic – in the interwar period – was similar to that of current open-source communities and led to licensing-out agreements and arrangements for the institution of patent pools. For antibiotics, this approach involved free access to new research tools, whereas for semiconductors it entailed cross-licensing and tacit agreements whereby there would be no recourse to legal action. This knowledge sharing approach depends in part on intellectual property tools but also on other factors: in certain cases governmental involvement or, more often, social norms, as was the case for the clubs of inventors that shaped aeronautics in its early stages. Thirdly, the intellectual property system itself has adapted to new technologies as they have emerged, as the case of antibiotics can aptly illustrate (Box 8.2). In relation to patent offices and courts, this refers to lines of inquiry on the patentability of these new technologies, the breadth of the claims, etc. Patent pools, partly on the basis of governmental intervention, have contributed to the development of the aeronautics system and its adjustment so that it could find an adequate balance. Fourthly, and taking into account that the technologies considered have essentially been conceived in developed countries, patents only partially account for the dissemination pace of these technologies towards developing countries. In this respect, their role is not determining either in a positive way – when this dissemination has been rapid – or in a negative way – when this dissemination has been slow. In this sense, the critical main factor has been undoubtedly the presence or absence of an absorption capacity, that is the ability of developing countries to learn and absorb the knowledge in question [WIP 15].

In relation to the current period and three types of emerging technologies studied by the WIPO (nanotechnologies, robotics, and 3D printing), it is emphasized that the lessons that we can learn from these three specific cases cannot necessarily be generalized. Nonetheless, it is concluded that the intellectual property system has played a significant role in each of the three sectors. Legal tools and patents in particular have played a significant and globally positive role by protecting the profits of R&D activities in these sectors, helping individuals reap the rewards of these activities, promoting further innovations thanks to the dissemination of technological knowledge, and facilitating the specialization of the actors concerned. Despite concerns about the large number of patents filed and the potential resulting risk posed by patent thickets, litigation involving intellectual property has remained infrequent so far. In relation to this topic, however, the technologies in question often have not been marketed yet, so that any empirical assessment will have to be made in the future.

Overall, as is the case for the three technologies studied in the context of the 20th Century, the WIPO reconfirms that for these three emerging technologies the intellectual property system has developed in tandem – and partially in synergy – with different knowledge sharing mechanisms, knowledge has been largely shared within several innovation communities through social norms, and finally the dissemination pace of these technologies towards developing countries once again depends mostly on the existence of absorption capacity in these countries.

8.4. Status quo, reform or abolition?

Taking into consideration these different elements for an overall review, should the intellectual property system be maintained as it is, reformed, or abolished? The issue arises all the more so as economists struggle to tell whether the existing system of intellectual property rights is a net positive contributor for the welfare of society as a whole.

8.4.1. A net benefit or a net cost for the economy and society as a whole?

This is true, for example, for trademarks. Naturally, some economists like [BOL 08] think that the contribution made by trademarks is positive and could hardly be debated. The opinions of others are more nuanced. Thus, [GRE 10] think that trademarks, despite improving the performances of the companies that use them on a microeconomic scale, may a priori mostly help large and wellestablished companies to limit the emergence of smaller-size newcomers on the market. Empirical studies hardly shed any light on this type of overall economic impact.

As for copyright and neighboring rights, we can see that the assessments made by legal experts, just like those of economists, differ. Some detractors think that the established propensity of these rights to grow in scope hinders creativity and innovation and that favoring the creations of the mind does not necessarily require protecting the entitled parties. Their alternative approach, called “copyleft”, argues more in favor of a reduction of the protection provided by copyright and the definition of “global public goods” [LES 01, LES 04]. It is true that the digital revolution has had paradoxical effects. By facilitating the possibility of copying or disseminating without the entitled parties’ authorization, it has produced a loss of income in the cinema and recorded music industry but, contrary to the predictions of economic theory, this does not seem to have caused a decrease in the offer of creative goods; the social acceptability of the copyright system is consequently greatly reduced [HAN 15].

Criticism of patents may also be harsh. For the United States, Jaffe and Lerner [JAF 04] underline problems related to the quality of patents, as well as the high costs linked to the patent system, and the high degree of uncertainty associated with the system regulating litigation and the practices of companies involving strategic patenting. They conclude that the patent system reduces innovation. Bessen and Meurer’s analysis [BES 08] is similar and regards this system as broken down and similar to the taxation of innovators. A highly regarded British magazine agrees with this analysis by extrapolating it beyond the specific case of the United States; it denounces the development of a parasitic ecosystem of trolls and entitled parties who do not hesitate to block innovation, “unless they can grab a share of the spoils” [THE 15]. We should recall that this magazine was already involved in a fight against the patent system in the mid-19th Century [MAC 50].

According to [BOL 08], whose criticism spares trademarks only to more radically attack copyright and patents, intellectual property rights constitute “intellectual monopolies” and as such they support a rent-seeking behavior and are used more to consolidate the interests of incumbent actors than challenge established positions through innovation. Boldrin and Levine [BOL 08], who go as far as comparing intellectual property rights to cancer, think that this is basically a battle of ideas that started in the Middle Ages and pits the forces of progress, the defenders of individual freedom, competition, and free trade against the obscurantist forces in favor of stagnation, regulation, monopoly and protectionism! Consequently, they argue in favor of a pure and simple abrogation of patents and copyright, just as they demand the total removal of obstacles to foreign trade. These two economists, affiliated with Washington University in St. Louis (Missouri), however, acknowledge that a brutal abrogation would be seriously detrimental in the short term and think that it would be better to organize it in stages by gradually reducing the term of protection [BOL 08].

Undoubtedly, other arguments really hit home as they are less dogmatic and more nuanced. Thus, it has been an established fact – especially since [LEV 87] – that in terms of ways of protecting innovation, the companies’ needs and the effects of their practices differ widely according to the sectors considered. If intellectual property rights play a globally positive role on innovation in several fields, they threaten to hinder it in other cases, in particular in the ICT sector, as they favor established actors to an excessive degree [OEC 14]. This refers to such sectors as the semiconductor industry or the industry of computer-implemented inventions, where the increasing number of patents mostly corresponds to the development of strategic uses of patents and leads to problematic patent thickets.

Similarly, the patent system produces effects whose global assessment in relation to the economy and society varies according to the perspective chosen. Thus, [LEV 03] think that intellectual property law – at least patents and copyright – has become globally harmful to innovation. However, they add that it also has positive effects by facilitating exchanges and promoting “the exploitation of ideas and creations by those who can develop them as well as possible”. Similarly, according to [POT 11], most empirical studies suggest that strong patent systems lead to ambiguous and somewhat uncertain results as a direct incentive for innovation and knowledge dissemination, despite tending more clearly to facilitate technology transfer and the emergence of technological knowledge markets. If we develop this idea, even if the main reference works do not include it yet, intellectual property rights contribute significantly to the organization of collaborative innovation, including the one between the corporate and the academic world. In summary, we should consider the effects of intellectual property rights on the global innovation process, including the issues related to funding, commercial exploitation, etc.

Besides, as Machlup was already explaining in his time [MAC 58], the patent system has in any case a fairly positive effect if we consider the dissemination of knowledge, despite certainly being partial and leaving some critics skeptical. The idea that the patent system facilitates the dissemination of technological information is indeed hardly debated. In addition, the effect of the patent system on income distribution is certainly one of the objectives of the system, so that inventive efforts can be rewarded, even if it is hard in practice to assess if the income deriving from patents and paid by consumers is perfectly proportioned and deserved. Finally, the incentivizing effect on invention and innovation activities must be weighed against the inherent cost of the system: the existence of patents is bound to limit the ability of third parties to use the technologies in question. In relation to this topic, [MAC 58] picks up an idea conceived before by a famous compatriot without quoting him: “cars, being equipped with brakes, go faster than they would without them” [SCH 42]. He points out that the braking effect, however, is more identifiable than acceleration, which remains a conjecture. Due to patents, in other words, the primary dead loss effect is unquestionable and “the incentivizing effects are secondary and speculative” [MAC 58]. Even if some inventions and innovations would have certainly taken shape without patents, he adds, the existence of patents can encourage companies to invest in the development of new products and technologies. In this sense, we need to distinguish between the logic of incentive and the logic of funding, and the patent system partly follows the second line of reasoning. In any case, this renowned Austrian economist thinks that it is impossible to reach a global assessment of the patent system, especially in the lack of counterfactuals: it is not possible to find out precisely what would have happened (or would happen) if such a system were not there. In sum, although there is a substantial amount of literature that presents definitive arguments about the economic consequences of the patent system, no theoretical or empirical line of reasoning allows us to ultimately validate or refute the hypothesis that the patent system has promoted technological progress and increased productivity gains. In other terms, no economist is in a position to say if the patent system globally represents a net benefit or a net cost for society [MAC 58].

Two generations later, several economists still agree with this conclusion. Posner [POS 05] adds that it is equally hard to give an opinion about the net profit or cost that other mechanisms encouraging innovation represent for society since, before suggesting that the system of formal intellectual property rights should be abrogated, it would be wise to consider that even alternative options have their own limitations.

The costs resulting from trade secrets are generally regarded as higher for society than those related to the patent system, in particular because establishing license agreements based on secrets is tricky and expensive, entailing especially the risk that the negotiation may inadvertently lead to the disclosure of the secret. This risk, for example, may dissuade a company holding some trade secret from outsourcing a production process that relies on this confidential knowledge, even if the choice of insourcing, which is guided by caution, involves production costs that are substantially higher than those of a potential subcontractor. Similarly, a manufacturing process that remains confidential as a precaution runs the actual risk of remaining limited to a single sector, instead of being applied to other sectors where it may lead to productivity gains, implying once again a cost for social welfare [POS 05]. Trade secrets represent a mechanism through which competitors can legally detect underlying knowledge only slowly by reverse engineering [ENC 06]. Out of all the mechanisms used to reap the rewards of innovation, it is the one that leads to the least amount of spillover effects for R&D activities, even if these dissemination effects represent a major source of productivity gains [COH 00].

If we leave trade secrets aside, what can we say of the other main mechanism that represents an alternative to formal intellectual property rights, that is having lead time and being the first mover on the market? This type of informal protection is not always relevant, in particular for young startups to which patents may, on the other hand, provide very useful signals to facilitate access to venture capital [CLA 13].

8.4.2. Reforming rather than abolishing

What kind of conclusion can we draw from this global assessment? “If we had no patent system, it would be irresponsible to suggest we should institute one. However, as we have been long equipped with a patent system, it would be irresponsible, based on our current knowledge, to suggest we should abolish it” [MAC 58]. The author of this famous sentence points out that “we” refers here to countries like the United States and that other smaller or still unindustrialized countries may draw another conclusion. According to him, the best policy involves making do with the patent system – for those countries that have had one for a long time – and continuing to do without one – for those countries that have not instituted one yet, which correspond to the least developed ones. In other terms, it is wise to avoid following Boldrin and Levine’s advice [BOL 08] and to decide against abrogating intellectual property rights. Furthermore, a similar observation can be made in relation to copyright: in the digital age, nothing tells us that abolishing it would be the appropriate solution [HAN 15]. Nonetheless, it would be wise to argue against the status quo and choose the path of reform. It is a matter of developing the system and adapting it as well as possible to the new socio-economic needs and technological changes. Experts like [GAL 02], thinking that it would be quite unlikely for all the patents that protect business methods, software, or biotechnologies to be suddenly discarded, conceive the system as developing on the edges and even through more fundamental changes.

8.4.3. The relation between innovation and the strength of rights: an inverted U-shape?

The three main directions that this reform should take have been pointed out in the previous chapter: correcting the scope of patentability, restoring the examination procedure of patent applications and introducing a filter for copyright, avoiding some excesses linked to litigation or blocking positions. As [GRE 10] explain, the effectiveness of the system of intellectual property rights depends largely on its precise configurations, i.e. the specific features and the conditions for the enforcement of each type of right. In several cases, we know the main long-established possibilities in terms of policy, but there are no empirical elements to assess their effectiveness. This is certainly why there is still a continuous need for reform. For the general direction of this necessary reform, it may also be useful to draw on three general conclusions drawn by [STI 08]. First, the importance of intellectual property rights should not be exaggerated. Secondly, our innovation systems include other instruments and mechanisms that deserve to be given more relative weight. Thirdly, we should reform the system of intellectual property rights to reduce its costs and increase its benefits.

Implicitly, the underlying idea here is that the protection provided by intellectual property rights is beneficial to innovation only to a certain degree, beyond which an extra extension globally impedes innovation instead of boosting it. This idea of a relationship with an inverted u-shape between innovation and the force of intellectual property rights is empirically borne out by several recent studies, among which [LER 08] and [QIA 07]. It helps us discard conventional models which, as [GAL 02] underlines, postulate the existence of a positive and monotonic relationship between the force of the protection provided by patents and the incentive to innovate. Generally, it is doubtful whether unrestrainedly reinforcing intellectual property systems leads to the promotion of innovation. As [BAT 15] explain, relatively weak patents may also encourage follow-on innovation by allowing later inventors to build on the basis of already patented ideas.

However, and in line with the results obtained by [AGH 05], these recent works also invalidate any simplistic theory similar to [BOL 08]’s, according to which, on the other hand, it is the total absence of intellectual property rights – that is the maximum degree of competition – that is necessarily most favorable to innovation. Therefore, the challenge is to find the right settings, all the more so since the suitability of the legal framework, which is relatively uniform, varies in relation to the different technological fields and industries.