4

How Companies Use Intellectual Property

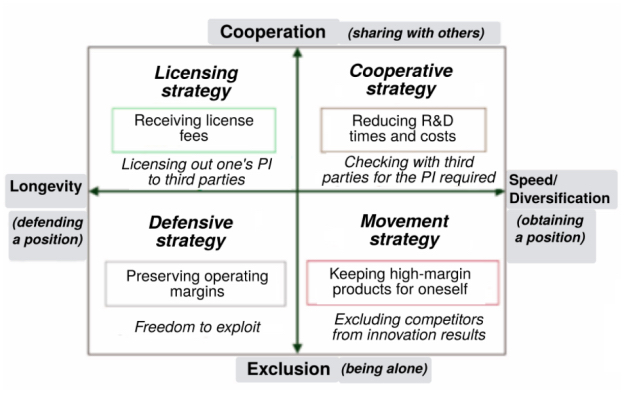

The number of ways in which companies use intellectual property keeps increasing. At first sight, they may be broadly classed into two main groups. A set of relatively classic uses can be contrasted with more recent practices well beyond the traditional role of innovation protection based on the right to exclude. We can distinguish between traditional uses that involve defending an already defined area so that it yields a sort of monopoly rent and uses which are more related to evolving strategies based on expansion or diversification. Corbel [COR 07] added another distinction to this dichotomy between a logic of exclusion and a logic of cooperation. The junction of this double series of oppositions allowed this author to outline a four-group classification (Figure 4.1), which mostly applies to patents but may also be partially relevant for other intellectual property tools. Somewhat restructured, this classification helps us distinguish between defensive, licensing, cooperative and movement strategy.

4.1. Defensive strategy

The first situation mainly corresponds to the traditional objective of defending innovation in a narrow sense, namely to ensure one can ward off the risk posed by counterfeiting or the infringement of rights, both preventively and repressively. In this case, the entitled party wants to ensure that they can produce goods and services that include the protected knowledge and obtain income after they have been put on the market, without risking direct competition in this respect from a rival. There are two things at stake. Not only should we make our competitors respect us but also ensure against inadvertently infringing their rights ourselves, as a company that wishes to become involved in a given activity must first check that it is not unwillingly infringing a third party’s intellectual property rights by studying its freedom to operate – namely by referring to patent and trademark registries, etc.

Despite being classic, these considerations about defensive strategies remain very relevant today. As for companies in the French manufacturing sector, Duguet and Kabla [DUG 98] have thus shown that the main reasons behind the use of patents are the desire to prevent imitation (92% of respondents), to avoid trials initiated by competitors (62% of cases), to use patents in technological negotiations (62%), to receive license fees (28%), to reward researchers (18%), and finally to enter foreign markets. For the German industrial companies surveyed by Blind et al. [BLI 06], obtaining protection against imitation is also the respondents’ first concern.

Figure 4.1. Four broad types of intellectual property strategies

(Source: [OLL 13] and [LAL 14a], drawn from [COR 07])

4.2. Licensing strategy

The second type of organization involves entitled parties who monetize their intellectual property through licensing. Thus, income does not derive from the direct use of the knowledge protected but from granting licenses to third parties in return for the payment of license fees. Several large companies have been relying on this method for a long time by transferring technologies deemed nonstrategic to third parties, but in general they use it at most as an additional financial source. Broadly speaking, companies only license out less than 10% of their patents [WIP 11]. What is new is that some companies – a net minority of them – base on this strategy a significant part of their business model. Most of these companies work in IT, telecommunications or the multimedia sector. This is the case, for example, for the Technicolor group, specialized in technologies designed for the media and entertainment industry and the French company with the highest number of patent applications at the EPO. Its intellectual property portfolio, which includes among other things more than 30,000 patents and patent applications, produced a net income of 490 million euros in 2014 and constitutes the foundations for most of its operational profit (Ebitda): 65% in 2014 and 78% in the first semester of 2015!

IBM, an American group, claims to have derived from its intellectual property portfolio a profit of 1.5 billion dollars in 1999, but most of this amount corresponds to the value of intellectual property assets sold. The actual sums resulting from its patent licensing program were markedly lower and hovered around 200 million dollars in 1999 (in 1992 dollars). Furthermore, this is a gross sum that does not take into consideration the fact that IBM pays several hundred patent lawyers for its licensing activity [BES 08].

This licensing strategy generally involves the threat of legal action and, in quite a few cases, the implementation of such actions to win against third parties accused of infringing rights and compel them to sign license contracts to solve their situation. The semiconductor industry illustrates this connection between licensing programs and litigation (Box 4.1).

Always considering the licenser’s point of view, there are several cases in the drug or medical equipment industry where patents allow startups to reach licensing-out agreements, namely to grant to third parties under license inventions that they do not use themselves.

Drawing up such licensing contracts is made much easier by intellectual property rights, both as exclusive rights and to the extent that they indicate the precise outlines of the intellectual assets in question. Without these rights, companies that can negotiate license agreements would be wary of disclosing their secret technological knowledge when it is easy to copy. By playing this role, intellectual property rights – and patents in particular – facilitate specialization in the innovation process [WIP 16].

On the technological knowledge market, these rights contribute to a sort of cognitive division of labor that entails as a benefit improved effectiveness on a global level, as they represent the main institutional foundations that allow knowledge markets to work properly while also favoring the specialization of the agents considered in relation to their comparative advantages [CIM 08]. Taking into consideration that companies in the best position to conceive inventions are not necessarily the most skilled in marketing them, it is a priori advantageous to society to organize transfers of knowledge among them. In line with this division of labor between inventors and innovators, Arora et al. [ARO 16] emphasize a specific category of actors they call technology specialists, who correspond to independent inventors, academics, and R&D service providers. They show that, when companies base their innovations on inventions acquired from third parties, the most highly valued inventions are acquired from these providers of specialized technologies.

Formal intellectual property rights, and patents in particular, facilitate the transfer of technological knowledge among businesses, on what Gans et al. [GAN 08] call the “market for ideas”. These experts, however, add that this market must be defined by effective and timely deadlines to work properly, so that an innovation can be quickly launched on the market. Yet, this market presents several imperfections, which are more or less significant in relation to the technological fields and generally derive from different phenomena: information asymmetry, search costs, difficulties in transferring tacit information to potential licensee, etc. To evaluate them properly, we should recall, for example, that a startup involved in a patent commercialization strategy with a partner must consider the right time to do this, since although an early agreement may increase productivity and enable a more rapid launch on the market, a later agreement may confer more negotiation power and enable a more effective technological transfer. Three main factors of uncertainty may thus influence a similar license agreement: uncertainty about the ability to enforce the patent and, prior to this, the very fact of whether this patent is effectively granted or not, but also the time it takes for a patent to be granted knowing that this period tends to be long but can vary quite a lot. In the United States, this period is estimated to be on average 28 months, but it can vary quite widely (standard deviation of 20 months). An agreement like this differs in relation to whether the patent in question has been already issued or not. If the patent application is still pending, there is also incertitude about its scope; moreover, this uncertainty is still present even after the granting of the patent, as a court may always limit the scope of the patent or even invalidate it at a later stage. We finally need to consider the very strong uncertainty about the economic value of the patent, which depends on several factors especially on a technological and business level. In the biopharmaceutical industry, for example, very few patented inventions end up being marketed [GAN 08].

The value of patents is therefore very uncertain and mostly unrelated to that of the underlying technologies. Taking also into consideration how high entry costs and potential litigation fees are, these “derivative markets for science and technology” remain very concentrated and dominated by large-size companies [CIM 08]. These various market frictions or weaknesses thus limit the development of the licensing strategy.

4.3. Cooperative strategy

Unlike the licenser’s point of view, which relies on licensing-out, a cooperative strategy relies mostly on the opposite perspective, namely licensing-in, which allows licensed individuals to legally exploit the intellectual assets of third parties. Relevant surveys about the United Kingdom (for the period between 2009 and 2012) and the United States (for 2003) show that purchasing technologies from third parties, whether through R&D services or similar license agreements, represented for these two countries 40% and 44% respectively of the companies’ total R&D spending [ARO 13]. The underlying logic mostly involves collaborative innovation, which is often called “open innovation”. It means that a company, in order to innovate, does not rely only on its internal resources but also draws on the knowledge coming from several external partners. From this perspective, which aims more to include than to exclude [COH 11], intellectual property rights can reduce certain costs and expedite some procedures by obtaining the cognitive resources of third parties, notably in return for license fees, and using these rights as assets that can be negotiated in collaborative innovation projects or following a logic of reciprocity. Generally speaking, companies that innovate in partnership may benefit from using tools like patents, as patents help them both define the respective rights of the different parties involved and find common ground especially during negotiations carried out by partners. This suggests that intellectual property rights, far from being a simple locking tool based on the right to exclude, may also cement collaborative innovation.

4.3.1. Intellectual property, between currency and a form of sharing

In some cases, this cooperative strategy involves sharing some intellectual property assets. It is especially required in the aforementioned case related to so-called complex technologies. The ICT sector illustrates this point. In this case, taking into consideration the emergence of the Internet and the convergence of the technologies associated with digital media, the implementation of new products or processes requires us to resort to a large number of complementary technologies and inevitably entails the unwilling infringement of the rights of third parties related to different patented technologies. Let us consider an example. A smartphone relies on multiple technologies that have to do with different sectors (wireless communication, GPS receivers, cameras, broadband network, etc.) and may be covered by up to 250,000 patents, according to Google’s legal officer. The companies in question therefore tend to build large patent portfolios to reduce the risk of finding themselves trapped by the competitors’ patents and use them as bargaining chips in negotiations with other patent holders [CHO 17].

In case of potential litigation between patent holders, there are other mechanisms – called patent trading – that make it possible to avoid expensive legal action or reduce it. The cost of a possible dispute is generally so high – especially in the United States – that lawsuits involving patents hardly ever reach their conclusion. A first solution involves compromising, namely solving things amicably, and is mainly chosen when the parties involved interact with one another and expect this to go on in the future. Other mechanisms involving the “trade” of intellectual property may entail among other things the exchange of patents, possibly supplemented by cash payments, or cross-licensing agreements [LAN 03].

The last practice involves companies or other types of organizations that exchange rights to mutually accept the use of their respective innovations. In doing so, companies reach a sort of standstill agreement. Once again, this type of practice is relatively common in lines of business that produce complex technological products, where the patents of the several entitled parties are mostly intertwined and the parties involved are consequently dependent on their competitors or partners’ patent rights. In this sort of situation, patents confer nonexclusive access to the market [COH 00]. They represent a development towards a “shared property” [ABE 05]. The semiconductor industry aptly illustrates this point (Box 4.2).

This type of strategy can also explain how the patents held by the large companies in question seem mostly “dormant”, at least at first sight. What is the purpose of these apparently unexploited patents that are not used by either the company that holds them or third parties through licensing? Their holders, who must pay annuities to maintain the validity of these apparently unused patents, may have a special interest in keeping them if they play a strategic role. Such patents may be used to increase bargaining power in cross-licensing or in line with mergers and acquisitions among companies [CIM 08].

Besides cross-licensing, another type of sharing involves the creation of what are traditionally called patent clusters or, more often, patent pools. By using these tools, innovators share a group of patents – which are often complementary – open to third parties through a common license. The first case of patent pool in the United States was observed in 1856 after several disputes in the sewing machine industry. Another historical case involves the aviation industry (Box 4.2). Although the number of patent pools mostly increased in the 1930s, today they have once again become relevant especially in ICT [WIP 11].

A more recent example of patent pools involves the coding standards for audiovisual objects implemented since the 1990s by the Moving Picture Experts Group (MPEG) consortium based on patent pools. This underlines the very significant link between intellectual property rights and technical norms (standards). These norms rely on agreements whereby the parties involved confer to each other rights of use in return for appropriate license-fee rates. If there is a risk that some of the entitled parties may accept to grant access to the basic patents for these norms only in exchange for excessive license fees, no empirical study seems to have established that they have thus abused the market power conferred to these patents [RAB 17]. Naturally, and especially in sectors where these norms are based on very fragmented intellectual property rights that occasionally involve hundreds of patents held by several companies, it is difficult to set the license-fee rate. Standards organizations generally ask the parties involved to disclose beforehand any patent that may be included in the norm and to commit to “fair, reasonable, and non-discriminatory” terms (FRAND). Competition authorities keep a watchful eye on this aspect, as this type of preliminary commitment about license fees may always be under suspicion of encouraging collusive behaviors in the holders of the patents considered. Although some patent pools may be advantageous by lowering the prices of the technology considered, others tend to increase their access cost [TIR 16].

Should cooperative strategies like these, especially via the implementation of patent pools, be regarded as excessively anticompetitive and entailing cartelization risks to the extent that the patent holders in question behave as a sort of oligopoly by using the accumulated patents to ward off potential competitors? Or should we think that such oligopolistic systems correspond most of all to the consumers’ needs? Competition authorities have reasons to support both cross-license agreements and patent pools. Thus, in the United States, the Antitrust guidelines about intellectual property licensing published in 1995 underlined that such agreements present some advantages, as they incorporate complementary technologies, reduce transaction costs, clear blocking positions, and avoid significant litigation costs [ENC 06].

Besides, as we point out below, we should regard so-called open source models not as the negation of intellectual property rights but as another type of intellectual property sharing. Investing substantially in a logic of shared and mutual access, they are involved in the cooperation strategy in their own way.

4.3.2. Patents as signaling tools, especially in relation to finance

Always in line with a logic of inclusion, companies also use rights such as patents as a signaling tool for several types of parties involved. Internally, some companies make an effort to reward, promote or keep the inventors they employ through incentive schemes, especially by awarding bonuses when patents are filed. Besides, patents are often used as signals aimed at establishing a technological reputation in the eyes of competitors, customers, venture-capital actors, banks or shareholders.

Thus, they play a key role in helping overcome the serious problem of information asymmetry which, classically, hinders the external funding of innovation. This is especially true for the funding of startups, for example in the drug or medical equipment industries. It is vital for these young companies with a marked technological component to obtain financial resources to cross the notorious “valley of death” of innovation, which is the critical phase that comes before the production and market introduction stage. Counting on patents that cover an early stage of the innovation processes allows startups to reassure investors about their ability to generate profits if the innovation is successfully marketed. These highly innovative startups can then use intellectual property as a collateral element to raise funds or as a contribution within the context of collaborative projects. A study focused on 829 SMBs and startups in which one of the nine main French venture capital funds has invested between 2002 and 2012 showed that those that file patents have much more chance of being successful [MEN 14].

Occasionally, patents can also be used as signaling tools for classic banks. A study involving more than 7,000 German companies observed between 2002 and 2007 shows that these firms manage, thanks to patents, to highlight to their main bank (Hausbank) the value of their R&D investments whereas, on the other hand, the banks in question do not turn out to be particularly responsive to the signaling effect that may derive from the fact that a company benefits from an investment in venture capital or receives a government subsidy [HOE 11].

Finally, patents are generally considered to have a positive effect on the stock-market valuation of the companies involved. When the Federal Court of Appeals in Washington denied Eli Lilly, a pharmaceutical company, on August 9 2000, a patent extension for the antidepressant Prozac, the share price of this society on the New York Stock Exchange fell by 31% the following day. Patents are not the only factors involved in these stock-market aspects. Trademarks also present major issues in this respect, and their value as intangible assets may often be very significant in cases of mergers and acquisitions. Consequently, it is crucial, yet not easy, to correctly assess the value of the companies’ intellectual property rights portfolios [LAL 08].

4.4. Movement strategy

Finally, a fourth type of strategy banks, as in the first case, on the exclusive power of rights – to ward off competition – but this time more offensively or preemptively than defensively, with the goal of gaining a strong economic position and excluding competitors by obtaining high-margin competitive positions. The notion of a “blocking patent” is often used to summarize this logic, which is in most cases similar to a sprint. This type of practice aims, in relation to the situation, to hinder rivals, send false signals to them, or even prevent them from patenting. Cohen et al. [COH 00] also refer to “preemptive patents”, insofar as filing certain patents may involve creating obstacles to prevent competitors from patenting related inventions. The notion of a blocking patent may be developed in different ways, which have been analyzed by [GRA 99] and more recently described in detail in Corbel and Le Bas’s work [COR 12]:

- – patent minefield: it somehow involves blanketing or flooding with patents that cover more or less significant inventions. Some minor patents are then used for their ability to do damage in order to slow down competitors;

- – fencing: in order to consolidate a key invention that has already been patented, this other type of strategy involves filing a series of patents that aim to cover different technological solutions that can potentially produce a result similar to that of the major invention, so as to block any alternative path available to the competitors. In this sense, a typical example is provided by DuPont. This company, in the wake of the first patent filed for nylon in February 1937, patented in the 1940s more than 200 substitutes for nylon, namely molecular variants of polymers with similar properties. Thus, this use of patents as obstacles to the detriment of competitors can be observed more in those sectors that rely on discontinuous technologies, like the chemical industry;

- – surrounding: a company may also surround an important patent held by a rival with a series of minor patents in order to block its commercial use;

- – decoy patenting: a company aware of being observed by its competitors, thinking that filing patents related to a certain technological sector may be interpreted as a sign that it desires to follow a given path, may carry out decoy patenting to try to mislead its competitors by dropping a red herring.

In nearly 19% of cases, patent holders claim that their patents are not used internally (commercially or industrially) or licensed out to another user, but that they are used exclusively to block competitors, according to the PatVal survey that considers 9,000 patents granted by the EPO between 1993 and 1997 and whose inventors are located in six Western European countries: Germany, Spain, France, Italy, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom [GIU 05].

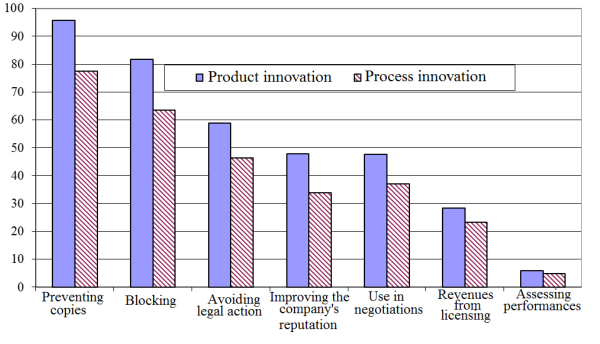

The relative significance of blocking patents has also been highlighted by the aforementioned Carnegie Mellon survey focused on industrial companies in the United States and the reasons why they resort to patents. As for product innovation, the desire to prevent rival companies from patenting related inventions – a motivation that corresponds to the notion of blocking patent – comes after the desire to prevent third parties from copying and before the protection against the risk of being taken to court for infringing the rights of others, the promotion of the company’s reputation, the reinforcement of its position in negotiations with other companies (especially in cross-licensing situations), the collection of license income and, finally, the assessment of the internal performance of engineers (Figure 4.2). The results obtained for process innovation are similar, even if the fourth and fifth place are inverted in comparison with the previous classification.

In practice, this movement strategy is particularly common in some sectors, especially in ICT where the increase in the number of patent filings is not only similar to an arms race but also often leads to actual “patent wars” (Box 4.3).

Figure 4.2. The main reasons why product and process innovation is patented (in % of the respondents) (Field: companies in the manufacturing sector involved in R&D activities in the United States.

Source: [COH 00])

These four categories (Figure 4.1) clearly represent ideal types. In reality, the companies’ practices often correspond to intermediate and hybrid situations. Thus, the movement and cooperative strategies may converge towards the goal of technological conquest based on speed. Let us consider an example. Some large companies – especially in ICT, the multimedia sector, and the software industry – deliberately release some of their inventions into the public domain or license them out to third parties either free of charge or on very advantageous terms. This way, they hope that the technologies in question will be adopted by users more quickly and in mass, and that in the long run they will become ipso facto essential standards on the markets considered. In other words, a strategy of technological conquest does not necessarily involve the maximization of revenue from licenses in the short term. This shows that a relatively liberal policy in terms of licensing out may help the dissemination of the technology involved both among partners and competitors. This scenario illustrates more generally the notion of “coopetition”, which combines a logic of cooperation and competition.

From a microeconomic perspective, similarly, these four ideal strategies (Figure 4.1) are often complementary and may be combined. For example, the same company may simultaneously carry out licensing-out and licensing-in activities. Similarly, patents are often double-edged as they involve a strategy that may include both a defensive component and an offensive dimension, provided that the company in question is able to win a dispute. In the sectors involving complex technologies analyzed by [COH 00], companies often use patents to protect their own inventions, block their competitors and take them hostage by controlling the technologies they need, and as bargaining chips in negotiations.

How these companies combine these different uses depends especially on the technological fields and sectors considered. Companies eager to make the most of their innovation effort learn from the developments in management either by strengthening their own internal ability to think strategically or by resorting to specialized consulting firms.

Overall, intellectual property rights are thus an essential aid for companies and help them to situate themselves in their environment as well as possible in relation to their competitors or partners. Their contribution is multifaceted and cannot be reduced to the rights to exclude, since these rights may be used in a context of cooperation or for inclusive goals [COH 11]. Furthermore, in addition to the most traditional uses that correspond in the present analysis to the defensive and licensing strategy, the last few years have seen the emergence of new uses that involve patents used as a negotiation tool for cross-licensing agreements, as a signaling tool, or as a way of preventing competitors from patenting for preemptive purposes.