2

How Companies Choose these Tools

Taking into consideration the diversity of mechanisms offered to companies to secure the product of an innovation effort and reap the rewards, which of them do companies choose? Why do they decide in favor of one rather than the other? To what extent can they combine these different tools? To what extent do they think that these tools are effective?

As for the preferences of companies in relation to the different ways of protecting innovation, a certain number of general results are well backed up. They have been first established by two pioneering empirical studies focused on companies in the manufacturing sector with R&D activities in the United States. One of them, carried out by Levin et al. [LEV 87], relies on a survey conducted at Yale University in 1983. The other, carried out by Cohen et al. [COH 00] is based on a survey conducted by Carnegie Mellon in 1994. These surveys provide information about the companies’ propensity to patent their innovations, that is the percentage of their inventions that they decide to patent. Both show that in most sectors – with the exception of the drug industry – the companies in question in general rely less on patents than other appropriation mechanisms such as trade secrets, lead time over competitors, or the use of complementary assets. Cohen et al. [COH 00] point out that even if the importance of patents has increased to a certain extent between the two studies – at least for large companies and in certain sectors – it remains less significant than these informal tools in most sectors.

This general result is not only valid for the United States. As is shown in Figure 2.1, it also holds true for the vast majority of European countries. It also applies to Japan, where companies generally give the priority to protection through lead time over competitors and the use of complementary assets in the manufacturing or sales sector [COH 02].

Similarly, studies focusing on companies in the manufacturing sector in the United States [COH 00] and France [DUG 98] agree on the main reasons why companies generally prefer not to file patents: the ease with which it is possible to “invent around” a patent, the fact that a patent cannot prevent imitation, the importance of the information disclosed in a patent application, the difficulty encountered in demonstrating the novelty of the invention in question, the fact that it is expensive to obtain and maintain a patent right and, finally, the fact that it is expensive to defend a patent in court in case of litigation.

It seems that companies often resort to a variety of mechanisms – formal or informal – to protect their inventions and that in most sectors they tend to combine different tools, whether to protect the same innovation or when an innovation includes aspects or components that may be protected independently of one another. Let us consider an example. Trademark law can be used to keep sales prices relatively high for a product whose patent has already come into the public domain. This is often the case in the pharmaceutical industry, even if the chemical composition of the drug in question is identical to that of a generic product sold at a much lower price. In the appropriate case, this is due to how the reputation of the originator drug, thanks to the brand, is more established than that of a competitor that produces a generic drug [POS 05]. As for informal tools, similarly, the protection provided by lead time over competitors may, for example, be reinforced by using trade secrets. A company can also protect itself against its rivals by both using intellectual property law – for example, through a registered trademark – and invoking the argument of unfair competition and parasitism, on the understanding that the notion of unfair competition is also included in the WTO’s TRIPS agreements. An innovative company may have to tackle this issue, for example, when dealing with a cybersquatter appropriating one of its Internet domain names.

These remarks about the complementary nature of protection mechanisms, however, must be nuanced. As Gallié and Legros [GAL 12] show in the case of France, complementarity plays a role mainly in relation to the different formal tools on one hand and the different informal mechanisms on the other; it is less involved on the whole within each of these two categories.

2.1. The factors behind the choice to use these different tools

These different means of protection may be combined not only at a given time but also over time. Besides, choosing one or the other may also depend on a multiplicity of other factors related in particular to the country considered, the size of the company, the line of business, but also the characteristics of the innovation process in question.

2.1.1. Differences according to the country considered

A company’s choice of a specific form of protection depends in part on the appropriability system relevant in the case considered. This system may be more or less strict in a specific country, especially according to the legal framework in place [TEE 86]. This helps us explain why companies in Japan consider patents to be some of the most effective forms of protection, whereas in the United States companies are much more willing to avail themselves of trade secrets [COH 02].

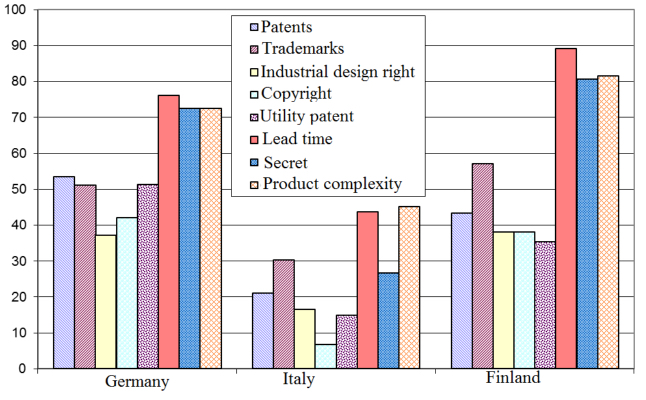

In Europe, the data collected from the Community Innovation Survey (CIS) confirms some general results that have already been mentioned in relation to the United States straight away. It indicates, in particular, that innovative industrial companies generally protect themselves much more often with informal mechanisms such as lead time over competitors, secrecy, or the complexity of products rather than with formal tools such as patents, trademarks, industrial design right, copyright, or utility patents (Figure 2.1). However, the data also shows that there are quite significant differences between countries. The use of different tools – whichever their kind – appears to be much less widespread in Italy than Germany or Finland, undoubtedly due in part to the differences in industrial structures between these three countries.

Figure 2.1. The share of companies using some forms of protection to protect their innovations (sorted according to the location of the company; in %). For a color version of this figure, see www.iste.co.uk/lallement/property.zip

(Source: based on the Eurostat data resulting from the 8th Community Innovation Survey [CIS 2012]. Scope: industrial companies (excluding construction) involved in product or process innovation for the period 2010–2012).

2.1.2. Differences according to the size of the company

Generally, large-size companies resort more often to patents than small- or medium-size businesses (SMB), partly due to the rather high costs related to patents. In particular, the latter are less able to meet the high costs involved in potential legal proceedings in case of litigation than the former [HAL 17]. Thus, if we assess the share of companies that claim to patent their most significant product innovations, namely the inventions corresponding to products that are new to the market, this propensity to patent is only 36% for small-size companies (less than 100 employees) versus 47% for medium-size companies (from 100 to 1,000 employees) and 63% for large businesses (employing more than 1,000 people), according to a survey carried out in 2010 on the American manufacturing system [ARO 16]. Based on French data, similarly, Duguet and Lelarge [DUG 12] confirm that the propensity to patent increases with the size of the company and is also positively linked to the fact that the company considered belongs to a group. Naturally, patents may represent a trump card for some SMBs, especially for the most dynamic young companies (startups) to which it provides actual bargaining power against larger partners. In any case, on a general level patents are mostly the business of large corporate groups. Conversely, trade secrets are the forms of protection most commonly used by SMBs, which may also prefer to protect themselves through lead time over competitors rather than patents, especially when they are involved in innovation activities in partnership with competitors [LEI 09, GAL 12].

2.1.3. Differences according to the stage in the innovation process

Another explanatory factor involves the issue of the right timing. Experience shows how some inventions have been patented too early in relation to their business development. To avoid this type of problem, the right thing to do is often to use different protection mechanisms one after the other at different stages in the relevant innovation process. Thus, a company may protect itself with trade secrets initially when a new technology must be developed, then with patents when the new product is about to be launched on the market, and afterwards with a business trademark or through lead time over the competitors.

This system can be illustrated by the company Bayer (IG Farben), which was a pioneer in the antibiotics industry at the very beginning of the 1930s. This company protected itself by keeping a large part of its invention secret. When it decided to patent the process for the production of the sulfa drug in question, it could hardly reap the expected rewards as its competitors rapidly managed to “invent around it”. Moreover, product innovations at the time were not patentable for drugs. However, Bayer was able to make its investments profitable by registering several trademarks (especially Streptozon and Prontosil) and investing in marketing for several decades when technology and uses of this drug had sufficiently developed [LES 07, WIP 15]. In robotics, moreover, experience has shown that inventions have been occasionally patented too early in relation to their commercial development, so that resorting to patents presents a cost-advantage ratio that sometimes seems too unfavorable in relation to alternative forms of appropriation [WIP 15].

2.1.4. Differences according to the type of innovation (process or product)

Patents tend to be used more often in relation to product innovation rather than process innovation. In the United States, 49% of product innovations and only 31% of process innovations are patented [COH 00]. As for France, [DUG 12] similarly show that the propensity to patent depends significantly on product innovation but not on process innovation. It is true that a product innovation is necessarily conspicuous and consequently involves a priori a high risk of being – through reverse engineering – detected and then imitated by competitors. This is not as true for process innovations. It may then seem more reasonable to rely on trade secrets and less necessary to protect oneself through patents. The relative effectiveness of trade secrets applies, for example, to the new processes in nanotechnologies, chemistry and the semiconductor industry.

As for product innovations, some sectors attach importance to several protection mechanisms without favoring a specific one. This is especially true for the drug and medical equipment industry, where patents are considered as relatively effective, almost as much as trade secrets or lead time over competitors. To protect product innovation, other sectors focus more clearly on a principal mechanism, for example lead time over competitors in the computer, communication engineering, steel, or car industry [COH 00].

2.1.5. Another key factor: the types of market or technology considered

The choice also depends on a certain number of characteristics related to the technologies and markets considered: magnitude of the profits derived from lead time over competitors, rate of emergence of innovative ideas, product lifetime or type of knowledge on which innovation relies.

Thus, when innovation involves a more tacit and uncodified type of knowledge, imitation is checked and delayed, so that protection through lead time over competitors or trade secrets may well suffice for the innovator in question to meet his or her R&D costs. This is not the case when knowledge can be easily articulated and outlined or in those fields – such as the drug industry – where it is based on science [ENC 06].

Similarly, choices vary a priori according to whether the innovation in question relies on technologies considered “complex” or “discontinuous”, namely in relation to whether it involves a high or limited number of components or manufacturing processes [LEV 87]. Broadly speaking, fairly discontinuous technologies involve sectors such as the chemical or pharmaceutical industry, where each invention (for example, a molecular structure or an active ingredient) may be protected by a small number of well-identified patents that allow their holder to implement the invention autonomously. Companies in this sector are very likely to rely on patents rather than trade secrets. As for so-called complex technologies, which are relevant, for example, for the electronic component or machine tool industries, the patents in question are, on the other hand, held by several entitled parties and generally used in groups to produce a wide range of different products. In the latter case, the possibility of “inventing around a patent” does not necessarily make resorting to patents an attractive option, and companies often prefer other forms of protection such as trade secrets and lead time over competitors [HAL 17]. On a global scale, patent applications are nevertheless increasing more quickly for complex rather than discontinuous technologies [WIP 11].

2.1.6. Marked preferences in relation to the sectors as well

Nowadays, the sector in which patents play the most central and fundamental role is undoubtedly the pharmaceutical industry (Box 2.1). Companies in this sector resort relatively less to trade secrets or lead time over competitors.

Generally, the producers of intermediate goods often rely on trade secrets, partly because their process innovations are not very likely to be detected through reverse engineering. Let us consider an example. Michelin has traditionally tried to remain secretive about a good deal of its tire-manufacturing processes, which often involve a sophisticated blend of technologies, in particular for aircraft or race car tires. The fact that in the last few years Michelin has been filing more patents is due not only to some significant cases of industrial espionage, since if the company does not file enough patents, it runs the risk of being prevented by its competitors’ patents from using technologies that it may have previously developed without disclosing its content but which its rivals may have devised by legal means such as reverse engineering.

In the sectors that produce (professional) capital goods, companies often rely much less on patents than first mover advantage, trade secrets, design complexity, or the use of complementary manufacturing capabilities. These are generally sectors that rely on the interaction of multiple components or manufacturing processes, as in the semiconductor and machine tool industries, in robotics, in the automotive sector and in the aerospace industry. In the last sector, the relative importance of patents as competitive or technological strategic tools is all the more reduced since historically the inventions designed have been often kept secret for reasons related to sovereign interest [COH 00, WIP 15].

The producers of household goods or consumer goods protect themselves from their competitors by using a wider range of tools, among which trademarks as well as industrial design right. Patents often play an important role for them, especially for businesses that have centered their development strategy on technological innovation. For example, this is the case for Dyson, a British company that invented bag-less vacuum cleaners that use “cyclone” technology. This company also claims to own more than a quarter of the global vacuum cleaner market share in value and has filed several thousand patents that cover more than 500 inventions. This is also true for SEB, a French company that has built a portfolio of around 5,000 active patents and has, for example, recently invented a “healthy” fryer that has already been sold more than five million times all over the world.

In the service sector and especially in the culture, leisure or software industry, companies use trademarks as well as copyright and neighboring rights. Most companies in these industries also use informal forms of appropriation, in particular by trying to lock in customers, suppliers, or employees [HAL 17], especially to reduce staff mobility [GAL 12]. Although a large part of them are hardly interested in technological innovation, the situation is often ambiguous for innovation in finance, the software industry and business methods, which in the last few years have been considered as patentable in certain countries. This problem arises mostly in the United States, where the possibility of patenting business methods was legally recognized in 1998. In the financial sector, in any case, the mechanisms that allow companies to recover their investments in R&D are above all the use of complementary assets and network externalities, as well as lead time over competitors. Taking into consideration that in this sector profit relies on risk – and consequently information – management, what encourages companies to launch new financial products is the prospect of being able to recover investment costs through the informational advantage related to the fact of being the first mover on the market [ENC 06].

These very significant sectorial peculiarities make it possible to put into perspective the records presented in the media about the “champions” of intellectual property from the point of view of the number of patents filed or granted. The number of patents is not particularly meaningful in absolute terms, as the propensity to patent inventions varies widely from sector to sector, just like the economic significance of each patent. The industrial sectors in which companies rely most heavily on patents are a priori those where R&D spending and the expenses linked to other related investments are the highest, such as the pharmaceutical or the oil extraction industry. However, the sectors that include the largest number of patents are rather those whose complex products are based on several components or manufacturing processes, as is the case in the electronics industry or car manufacturing.

Therefore, several factors determine not only a company’s propensity to protect innovation through a specific form of protection but also the economic importance that it attaches to it.

2.2. The microeconomic effectiveness of protection

Several questions arise in relation to the compared effectiveness of these different mechanisms used to protect innovation from the point of view of the company that relies on them. More specifically, which links are there between patents and the companies’ performances in terms of innovation? Are patents necessary to drive innovation on a microeconomic level? From the users’ point of view, what is their effect on innovation? What do we know about the private value of patents and the added value they contribute to the innovations in question?

2.2.1. Which contribution is made to performances in terms of innovation?

Most empirical studies that analyze the connections between intellectual property and innovation in terms of microeconomic effectiveness focus on the interactions between patents, R&D and technological innovation.

Mansfield’s survey [MAN 86], which was carried out on a sample of 100 companies in the manufacturing system in the United States, shows that most of their inventions in the period between 1981 and 1983 would have been developed anyway in the absence of patents. According to the respondents, however, this is not the case for the pharmaceutical and chemical industry, where the companies surveyed report very substantial incentivizing effects. Even in the large number of cases in which companies regard the incentivizing effect of patents as weak, the study suggests that they prefer not to rely exclusively on trade secrets, when they have the opportunity to patent, and that they patent most patentable inventions. In the automotive industry, where the respondents often report that patents do not play a significant role, nearly 60% of patentable inventions are reported to be patented [MAN 86].

More recently and beyond descriptive statistics, econometric works have managed to point out the relationships between the use of different tools for the protection of innovation and the companies’ performances. Based on British data, the works carried out by Hall et al. [HAL 13] established that there is a positive link between the fact that companies claim to prefer patents and their innovation performance assessed on the basis of the share of innovative products in their turnover. On the other hand, this work hardly identifies any relationship between the preference for patents and other performance measurements focusing inter alia on employment growth.

Controlling several variables through econometrics, [HAL 17] managed to obtain an interesting double result concerning innovative British companies. On one hand, those firms that attach a lot of importance to the formal tools of intellectual property carry out innovation activities that on average ensure them a productivity level that is 10 to 20% higher, all other things being equal. On the other hand, the same result cannot be obtained for innovative companies that prefer informal types of protection, except maybe for large-size companies. Due to several methodological limitations and in the lack of indications about the quality of the innovations in question, the study is careful not to draw the conclusion that all companies should convert to the formal tools of intellectual property for all their innovation activities.

2.2.2. Which links are there between patents and R&D profitability?

Other works analyze the effect of patents on the private returns to R&D and, in turn, the consequences of this private profitability on firms’ R&D expenditures and the use of patents. We can include here the study carried out by [ARO 08] based on the aforementioned survey conducted by Carnegie-Mellon. This is also true for a similar study carried out by [DUG 12] based on French data. Adopting the same kind of econometric approach, these two works attempt, among other things, to determine the premium provided by patents (Box 2.2).

These econometric works therefore confirm that, apart from a small number of sectors, patents occupy overall a less central place than other mechanisms in the protection of inventions. However, they also reveal that in all the industrial sectors considered some inventions are worth being patented. These works also point out that the protection provided by patents affects product innovation but has no significant effect on process innovation. Furthermore, they lead us to an important conclusion: a given increase of the patent premium generates a disproportionate growth of activity in terms of patents in relation to the resulting consequences on R&D.

2.2.3. What is the value of patents? Between cost-benefit calculations and lottery logic

The question of the added value provided by a specific form of protection may also be approached as the result of cost-benefit calculations. If we consider patents, there are several costs involved, some of which are certain or may be predicted. This is especially true for filing fees, the annuities involved in maintaining the rights once the patent has been issued, the expenses incurred in making sure that competitors do not infringe the rights, as well as the cost of a disclosure that facilitates the competitors’ imitation. A patent does not generally allow an innovator to recover the whole value of his or her invention: the underlying ideas tend in most cases to spread to the advantage of third parties. Other aspects are much more uncertain and can hardly be predicted, especially in relation to the benefits expected. This uncertainty also concerns the costs involved in potential disputes both from the plaintiffs and the defendants’ point of view, since the outcome of legal proceedings or settlement agreements is very unpredictable.

As Lemley and Shapiro [LEM 05] explain, most patents have hardly any value, either because they are applied to technologies with scarce business potential or because it is difficult to defend them in case of dispute, but also because it is not very likely that they will hold up if litigated. In this context and in particular in the United States, filing a patent is very similar to buying a lottery ticket: the down-payment very rarely turns out to be profitable but in cases of success the profits may be considerable. Due to these legal or economic contingencies, patents can be considered as probabilistic rights.

Several empirical works confirm this by showing that the value of patents is highly concentrated in a small number of them [GIU 05, LEB 07]. Despite this uncertainty problem, some experts think that the issue of the microeconomic performance of patents, from an innovator’s point of view, may be examined in terms of cost-benefit calculations. This is especially the case for Bessen and Meurer [BES 08], who leave aside the issue of the effects of the patent system on society as a whole. These two experts, affiliated to the University of Boston, think that before concerning ourselves with this aspect, we should answer a central question: do patents provide a positive incentive in net terms for inventors or not?

According to them, patents are generally a source of income for their holders, so it is sensible to obtain them. However, taking into consideration the patents of third parties may make a difference, especially due to the risks and costs involved in litigation. Their estimated figures show that the income coming from patents is not very significant on the whole. In total, the incentives provided by the patent system are generally very positive for companies in the chemico-pharmaceutical industry. Nonetheless, on a global level this is hardly the case for other sectors where the benefits have more or less balanced the costs for most of the period studied (1984 to 1999). Most importantly, the companies of these other sectors have even been faced with a growing net cost since 1994, due to the explosion of the costs involved in legal disputes. Arguably, some evidence shows that this problem has become worse since 1999. Around the end of the period studied, in other terms, patents globally had an effect that was more deterring than incentivizing on the companies of these other sectors. The authors conclude that patents, despite generating significant income for some groups of innovators, do not generally represent the main means of encouraging innovation and that on average they contribute to it only modestly.

At the microeconomic level, the empirical analysis of the effects of patents on innovation produces mixed results which, nonetheless, agree on certain points. This analysis clearly indicates that companies in most sectors hardly rely on patents as their main form of protection. However, it does not deny that this protection tool may give some value to the underlying inventions. On the contrary, several studies focusing on this topic can identify, for the firm that avails itself of patents, an incentivizing effect of the protection provided by patents on R&D and innovation, at least in some sectors (essentially the pharmaceutical industry, biotechnologies and the medical equipment industry) and more or less markedly according to the period. However, demonstrating the private value of patents is not enough to establish their social value. Thus, the fact that patents have the potential to drive innovation activities on a microeconomic scale does not by any means entail that their effect is positive in terms of collective welfare in relation to a sector or the whole of the economy and society.