3

Born Global

3.1. Definition

Terminologically speaking, “born global” organizations are a recent introduction. Other expressions are also used, such as “fast and early internationalization”, but based on close boundaries. It is a matter of characterizing firms or organizations that have a relationship with different parts of the world that are more complex than exporting firms, even if the most commonly used statistical criterion, namely more than 25% of international activity before the end of the first 3 years of activity, does not make it possible to distinguish clearly between a “born exporting firm” and a “born global” firm.

The term “born global” was introduced following the observation of bimodal distribution for internationalization criteria. In 1993, the time that a new Australian company took to internationalize concerned two types: companies took 27 years on average, and others did it in 2 years at most.

An Australian study indicated that the phenomenon was encountered in all sectors, not just in high-tech ones. For new enterprise projects, “global” projects are generally larger in size and often appear in around half of countries, such as Belgium and Romania.

There are many indicators of globalization: regions well integrated into intensive trade flows will have a high rate of business start-ups called “born global” and this rate will decrease for less well-integrated regions and those with fewer connections to networks. OECD studies confirm that the global “average time” of internationalization was reduced by about half between the 1980s and 1990s, a change that also affected small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), whereas literature only previously took into account very large multinational firms.

This focus is perpetuated in most theories of globalization, including that by Ohmae, which envisages only enlargement situations from a large existing firm.

A pioneering article [OVI 94] indicates that the theoretical approaches of organizations remain relevant for the “globalized” firms, but the phenomenon accelerating internationalization is not explained in the set of analysis tools built in the 1960s around multinational firms. This in turn weakens the foundations for a new, more appropriate theoretical framework to be sought.

Previous analytical tools, gathered in a paradigm elaborated by the University of Uppsala in 1970s, promoted a step-by-step, progressive and evolutionary internationalization of firms. They drew on both international theories of trade and management.

Among these tools, the OLI (Ownership–Location–Internalization) paradigm requires three conditions for overseas establishment: the firm must have a strategic advantage, the distant country has a localization advantage and organizational costs are such that the internal solution is mostly profitable.

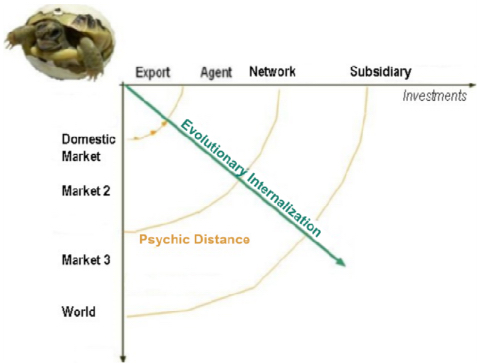

If the firm has only a strategic advantage, it can use a license sale for example; if it has this strategic advantage and internalization, it will develop a proprietary sales network, and finally, only if the situation meets the three conditions of the OLI paradigm, then a direct investment abroad must be considered. These same stages are found in the paradigm presented by the University of Uppsala [JOH 77]: first there are opportunistic exports, then the use of an independent agent, then the creation of a sales subsidiary and finally a production site in a foreign country. The implicit assumptions mean that internationalization is seen as a long and delicate process of learning based on psychological distance between countries, which makes it possible to classify them in relation to the source country. This psychic distance can be reduced by experience. It is requested that companies undertake internationalization from countries with a lower psychological distance.

Ohmae’s theory of globalization is already out of step with this Uppsala paradigm. The theory portrays an equitable manager in a multisite situation. The manager arbitrates objectively within a group of companies present in several parts of the world. However, according to Ohmae, the relationship between globalization and innovation is conceived in the context of intercompany agreements and enlargements. “Globalized” firms are a new variation of the relationship present in research studies and are decisive factors of innovation between globalization and innovative attitude. Globalized firms reflect an evolution in the statistics organizations that collect data on world trade. The initial statistical signature of these “global” firms is not that of a technological shock linked to the emergence of the Internet, as it was registered before the creation in 1999 of major platforms such as Alibaba, specialized in industrial trade, and all sectors are affected. Statistically, it is indeed a progression of globalization that is recorded, progress that will be consolidated by development platforms like Alibaba, itself a multiplier of “born global” firms [EVA 17].

Three cases illustrate a definition of the born global organization and present the stakes of this new relationship between globalization and innovation. First, a counterexample, in other words, a firm that remains in the Uppsala paradigm, one that is progressive in terms of internationalization: Nutriset. Then the Alibaba group created by Jack Ma is discussed. It is an emblematic stakeholder in terms of the arrival of born global firms. And finally, an example of luxury pastries distributed in the form of born global firms, indicating the great generality in terms of sector activity of this new type of organizational behavior directly related to innovation and globalization.

To summarize, the following list of criteria fulfilled in order to be a “born global” organization can be proposed based on a European study [EUR 12; p. 63]:

- 1) the firm or organization is independent;

- 2) it has an internationalization dimension;

- 3) it is internationalized in at least two different foreign countries;

- 4) it offers an innovative product or service;

- 5) it carries out more than 25% of its export activity during at least 2 years of the first 5 years of its existence. The size of the reference region for measuring the external activity rate is that of a German Länder type.

3.2. The two worlds of born global organizations

Studies on born global firms are now numerous; more than 1,000 have been cataloged by a Swedish team [AND 15]. They are usually of an empirical nature, based on a Länder type, and apply either a simplified criterion (dummy variable, 0 or 1 if the firm exceeds 25% export activity in the first 3 years) or a more sophisticated one, of the Eurofound type to select firms born global. Regardless of the criterion, two main types of situations are easily distinguished, either low rates of born global firms or those with high values. Low rates, about 12% with a dummy variable, correspond to a local entrepreneurial rate higher than 50%; respectively, the local entrepreneurial rate less than 50% corresponds to high values of dummy variable of born global firms.

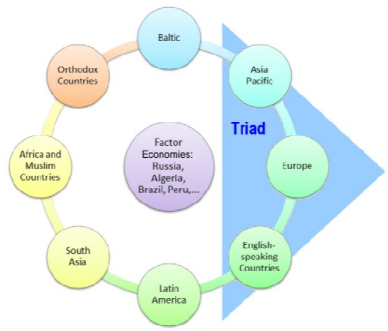

Annual data from the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) are presented in three groups of countries, factor economies, an intermediate group and innovation economies, according to an increasing value of the standard variable of internationalization as “over 25% of start-up activity leads to export” [GLO 17]. A country like China as a whole is going to have indicators derived from averages of all Chinese regions that rank China in a factor economy. But the regional indicators are not homogeneous: mostly the Chinese regions only know of local entrepreneurship, except coastal regions that have very high values of born global companies. By using a well-defined criterion for interior regions, the distribution is bimodal, and it is more consistent to retain two typical situations, even if the entrepreneurship is predominantly local or not.

When entrepreneurship is predominantly local, business creation is on average rather low. Overall, the density of newly established born global firms is well below the global average. For regions where there are a large number of firms, they can be distinguished according to the world average density of new born global firms in the Triad countries. Regions are most often still below this average, while in cities like Singapore, this rate is higher than the global average. In the European Union of 28 countries, 15 countries are in the triad rates, four countries have a majority local entrepreneurship (2013 data: Spain, Finland, Italy, United Kingdom) and nine countries have a cosmopolitan creation of born global firms (Luxembourg, Slovakia, Baltic countries, Romania, Portugal, Slovenia and Croatia).

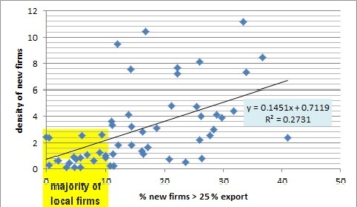

Figure 3.2. Density of new enterprises and rapid internationalization (by countries in the World, 2013)

The following three sections detail some characteristics of born global organizations in the majority of local entrepreneurship regions (section 3.2.1), then minority (section 3.2.2) and a summary of elements common to all regions (section 3.2.3).

3.2.1. Born global firms in regions with a majority of local entrepreneurship

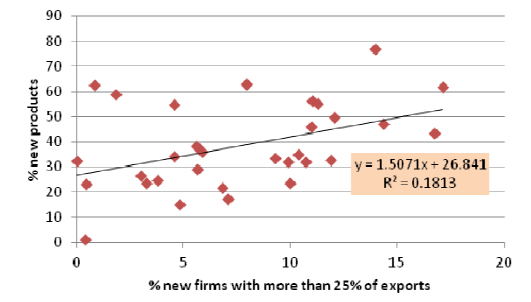

In these regions, the start-ups of new activities do little in the organizational form of born global firms. There is a positive correlation between proposing a new product and the rate of internationalization: in regions where young firms offer more new products we will have more organizations with rapid internationalization (see Figure 3.2). In regions where young firms are less numerous and mostly limited to local markets, global firms and innovation go hand in hand (see Figure 3.3).

Figure 3.3. New products and rapid internationalization in local entrepreneurship regions

In the global indicators, large subregions act to explain the classification of different continents. At the bottom of the list are Asia and Latin America, where, on average, the phenomenon of born global firms is the least present. Chinese inland provinces, Indonesia, Malaysia for Asia and Brazil for Latin America have so few global firms compared to the rest of the world, it plunges the indicators of their respective continent.

A study of a Chinese interior province (Sichuan, on the edge of the Tibetan plateau) concludes that there is “an inadequate institutional environment” [ZHA 10]. The contrast between Malaysia and Singapore, at the extremes of the GEM rankings, corroborates this view on these highly contrasted situations induced by public policies. An article on Brazil states that “traditional internationalizations have governmental and local resources”, in contrast with Brazilian global firms, which can only exist through business partnerships or a strong integration into sector value chains [RIB 10]. The industries in the Sichuan province are mainly large traditional exporting factories, whose founding dates back to the 1980s. The few born global firms are a relatively recent creation and remain small. These born global firms have much more competence in internationalization than the traditional exporting firms. Public policy is a policy of development of these interior regions with infrastructure and voluntarist urbanization. The resources and skills needed to conduct internationalization remain particularly scarce in these Chinese regions [ZHA 10]. Developing entrepreneurial skills for internationalization is the positive recommendation of these studies carried out in areas where global firms exist only due to a few personalities or some partnerships with very strong cohesion resulting from interindustrial or interorganizational relations.

3.2.2. Born global firms in open regions

The criterion of local entrepreneurship above or below the majority (except for eight of the 70 countries in the GEM sample) divides the regions according to GEM denominations: that is, regions with a majority of new local entrepreneurs and which are in a factor-saving situation – for example, Algeria, which exports hydrocarbons, or Bangladesh, whose resources come from the textile-clothing sector alone. The majority of new entrepreneurs have a non-zero outside rate of activity, corresponding to innovation economies in the denomination GEM. For a factor market, improving the variety of exported products can be important (see Figure 3.3).

European Union countries, as well as Singapore, have the highest rates of born global firms. Regions dominated by new local businesses have a significant share of services to professionals (22.8% in 2013). The sectors that bring together the most new businesses in the open regions are consumer services (59.7% in 2013). Primary and secondary sectors, as well as logistics, remain in equal proportion, on average, in both types of region. A study of Chilean start-ups confirms that they are in all sectors and at all technological levels. The factors accelerating Chile’s internationalization in descending order of importance are: linking up with distant markets, belonging to a Chilean network of internationalization support, and location in Santiago, the urban area of Chile. In continents with low incidence of born global firms, such as in Latin America and Asia, the business creation space viewed in terms of internationalization is highly polarized: on the one hand, cities such as Singapore or Santiago and, on the other hand, whole countries where local economic policies are of old and diverse design. The various sectors have different institutional solutions for property rights, but on a global scale, the polarization of large spaces is explained in this monograph by concepts of public economy (a support agency specialized in accelerating internationalization), and political economy in a strategy to include Chilean producers in Northern Hemisphere markets [CAN 14].

In the Chinese coastal province of Zhejiang, born global firms are SMEs that are active in foreign and domestic markets. There is sometimes a price gap, as well as late payments on the domestic market that encourage international development. The leaders of these SMEs do not perceive the “psychic distance” from other countries. They are experienced in foreign markets and graduates of higher education. The Zhejiang region is China’s fourth largest economic region, with more than 22% of SMEs ranked among China’s top 500 according to a competitiveness criterion [MER 14].

In places with the highest rates of born global firms, spatial disparities are mitigated. The term “city or creative class” is more appropriate for highly polarized spaces. The creation rates of global start-ups are rising and the differences between cities and between urbanized areas and the rest of the territory are decreasing. In this context, global start-up projects are larger than others, and thus the size effect is the reverse of what is found, for example, in Chinese inland provinces, where global SMEs are a notch below the size of other exporting firms. For studies in European countries, “global” enterprise projects employ more labor from the start, favoring organizational growth in the face of short-term profitability and individual productivity. They are more innovation oriented and have more trained leaders. The quality of preparation for a project is better for born global organizations in the creation of a company. The jobs created are of good quality and the wage conditions are satisfactory. Studies in European industrial sectors put forward a rapid explanation of internationalization through socialization networks (importance of flows, alliances and interindustrial relations) [EUR 12].

The explanations for a slowing down in internationalization are in line with those lengthening the beginning of the product cycle. The most intensive start-ups in research may prove to be slower in internationalization, even if adaptations are to be expected.

3.2.3. A convergence of organizational form

Do global companies have different characteristics in different parts of the world? Public policies are very diverse, but they are not included in the most studied determinants in literature on born global firms. On the contrary, entrepreneurial skills are placed at the forefront of explanations of rapidly internationalizing organization phenomena, regardless of the region of study. Studies in regions with a polarized space, with a city emerging from regions dominated by local entrepreneurship, do, however, provide the most analysis on institutional and political environments. The literature in regions with a good density of born global organizations is much more accurate in the details of the firm’s internal procedures. However, comparisons only detect differences regarding external elements such as public policy, or focus on internal organizational aspects, which are rarely addressed in the literature on Latin America or Asia. The importance of networks, bonds of trust and informal alliances among entrepreneurs is emphasized throughout the literature [AND 15].

A fairly unified image of global organization emerged from these confrontations. There are positive operators of change of scale, fast internationalization support agencies, interprofessional trade sites, universities and large firms. The competent entrepreneur and the reliability of networks are decisive. Factors external to the organization play more of a role during the initial phase of growth and internal factors in its sustainability in the longer term [EFR 12].

3.3. The born global organization: a new paradigm

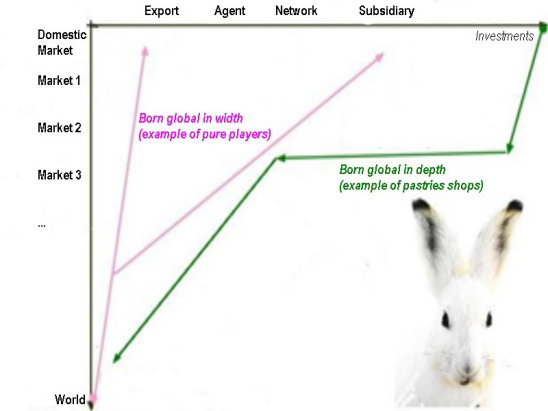

As soon as the Uppsala paradigm was established, it was noted that many companies did not follow the prescribed steps, such as selling first on the local market, waiting and then exporting. On the other hand, the theoretical determinations of the Uppsala paradigm, such as “psychic distance” between countries and cultures, appeared fragile. The communities of users, for example, of industrial goods can bring together professionals with the same technical knowledge all over the world, so that “psychic distance” brings not a step-by-step process, but a policy which must be international to reach all potential customers. Empirical studies indicate width-related management (as in the example above), or at depth, whereas the Uppsala paradigm would require stepped management, i.e. diagonal progressing both in width and depth [MOO 10].

The dynamic is rather a self-reinforcement of each strategy: the company chooses a strategy along an axis – either in width, the axis markets; or in depth, the axis of direct investment abroad – is reinforced in its strategy. The existence of two conventions means that the “diagonal strategy” proposed by the Uppsala paradigm is very unstable; any gap will make the company join a global strategy either in width or in depth [MOO 10]. Pure players provide examples of global organization with a broad strategy. The example of luxury pastries (see Box 3.3) is an in-depth strategy convention: the pioneer Hermé traced a path through Paris and Tokyo, the novice who tried to move away from this path returned after an unsuccessful attempt in Miami. The Alibaba group (see Box 3.2) presented a strategic shift: the group had more presence in the Chinese market due to competition from eBay and created the Taobao subsidiary (see Figure 3.5, trajectory of born global firms in width).

Figure 3.5. The paradigm of the born global organization

More complex scenarios follow stages of expansion and consolidation. Internationalization follows a progression through large jumps in temporal expansion. Internationalization consumes mostly human resources, with man-to-material ratios not being very capital intensive, that is to say, mainly people and few machines and infrastructures. Consolidation episodes are more capital intensive and managed in a progressive way [OMO 10].

3.3.1. Redesign of the theoretical bases: intellectual rights, learning, intercultural distance

The example, the new management of malnutrition (see Box 3.1), indicates that a very defensive idea of intellectual rights does not always correspond to social utility. A letter in 2009 from doctors (NGO Doctors Without Borders) to the Nutriset company, asked them to speed up movement by updating its idea of protection innovation. Intellectual rights can be legally protected over long periods of time, such as the unavailability of a drug for a large number of patients. To avoid the most damaging forms of intellectual property protection, legal alternatives exist and their relevance is supported by economic literature [FOR 13, TIR 16, CRO 17]. These legal alternatives are also defended by promoters of collaborative economy [NOV 14].

The Uppsala paradigm is based on gradual learning. Today, the behavior of organizations is rather a generalization to many countries, either by adopting the same marketing technique (management in width), or selecting locations that concentrate investments (management in depth), i.e. by avoiding the stepwise learning system each time. The Uppsala paradigm prescribes changes in marketing techniques due to physical remoteness of markets: it is not certain that it will lead to reducing uncertainty. It would be less risky to facilitate learning either by retaining the same market or the same marketing technique and that is what companies do. The organization values its own resources and know-how, either knowledge of a market or the marketing technique. The entrepreneur’s initial competence in internationalization is decisive [LAG 09].

Difficulties requiring lengthy learning are concentrated on the management and creation of high-tech firms. These are only a part of the global organizations, but this means that the greatest intercultural distance is due to technology. This calls into question the central notion of “psychic distance” specific to the Uppsala paradigm, favoring differences in norms, values and behaviors. C.A.G.E.T. is a multicriterional redefinition of this “psychic” distance.

The five dimensions of C.A.G.E.T distance are:

- – intercultural distance: differences in beliefs, values and norms between two regions;

- – administrative distance: differences in regulatory approaches and conditions for companies. Some countries have a close administrative distance. For example, there is a significant gap with the United States in health legislation for trades such as pastry making using fresh produce (see Box 3.3);

- – geographical distance: transport costs, climatic conditions;

- – economic distance: the difference in purchasing power in different countries;

- – technological distance: the difference in consumer preferences in technology, responsiveness to innovation and accessibility of technologies and services across regions.

In the Uppsala paradigm, the only case envisaged is a blocking factor arising from a cultural factor. For born global organizations, this can come from innovation and other factors are detailed in the C.A.G.E.T list.

3.3.2. An entrepreneurial paradigm of simplicity

The launch of the Logan car on the market marked a transition for the Renault-Dacia-Nissan group from a strategy of expansion based on adaptation to a born global market strategy. Entry level Logan vehicles make up about half of world sales in the group. This transformation was recounted by its main players with regard to potentialities and not deliberate strategies: the unexpected commercial success of the Dacia vehicles has resulted in the reorganization of the group’s strategy. In approximately 1995, the group’s management was aware of the need to renew the vehicles sold on the small Romanian and Russian markets. An autonomous team was appointed to carry out this project, which also needed to take into account the limited budget of Romanian families. The modernization of Romanian factories allowed them to develop a range that is marketed today all over the world, with only minor local adaptations of vehicle types. In renewal markets, vehicle types were moving toward sophistication due to competition. Reflecting on what would be a vehicle adapted to the Romanian context, i.e. the range, they proposed vehicle types for new users in emerging countries and for users who would prefer a new vehicle to purchase on the second-hand market. The slogan of simplicity can be understood as a search to diminish technological distance. The service or product has to be simple, in other words, a reduced distance with the consumer.

Several invariant themes appear in research on the determiners of performance of the born global organization. Some are not specific to rapid internationalization, such as recommendations on building a network by establishing trust, and recruiting competent people. The difficulties associated with a period of strong growth in regard to the organization are shared by born global firms, but are not specific to them. Entrepreneurial and innovative content, on the other hand, is superior to all companies and already represents a more specific character. Born global organizations are involved in rapid internationalization: it may or may not be a part of a collaborative economy, which can itself be a purely local organization. Thus, collaborative economics and global organization are two distinct concepts, even though they are often associated with the same organization.

The two themes that seem to us to be the most recurrent and shared in theoretical essays on the paradigm of born global organizations are achievement and simplicity. The founder of Alibaba, as well as the testimonies of the introduction of the new entry-level in the Renault-Dacia-Nissan group, also corroborates the preeminence of these themes. During realization, it is opportunities that are decisive. Whether it is for Alibaba, or for the Dacia range, things really did not go as planned. These were opportunities that were decisive. Constraints have been transformed into development lines. The promoters of rapid internationalization did not have great competence in new technologies, or in international markets. A great deal of expertise leads to rather sophisticated developments. Entrepreneurs develop a simple idea with the means at their disposal. The less important uncertainty is, people have a buying decision and who may be concerned, for example, with the low reliability of older vehicles.

3.4. Collaborative economics and born global organizations

Collaborative economics brings together forms of collaboration used today in mobile phone and Internet applications. These forms of collaboration can be divided into three groups: the collaborative practices themselves, the provision of a good or a resource and participatory finance. The Cochrane Collaboration and Wikipedia are examples of the first case, Blablacar, Airbnb, Uber, the second.

Collaborative economics can be purely local, on an intermediate scale, or combine in different ways from local to global coordination. For example, the Ushahidi site is a website for collecting testimonies about political violence in Kenya occurring during election periods. This collaborative site was able to indicate the extent of violence in the 2007 elections. In the same way, an earthquake relief situation can be based on a collaborative site, coordinating rescue teams for the various sites, clearing bodies and sites led by victims’ relatives to contribute to the rapid restoration of social life. In the first case, the system leads actors to arbitration and compensation: the teams will go to one place due to necessity. In the second case, there is a connection between natural persons who are remote from the earthquake and who are rescuing a group of victims in a peer-to-peer relationship without arbitration or compensation from the system.

3.4.1. Creative destruction?

While the definition of collaborative economics has no intrinsic link with rapid internationalization, the Internet does provide coordination at a lower cost, and promotes new organizational forms, particularly born global. Clay Shirky, a New York Times columnist on the future of the press, created a scandal in 2009 after a declaration on a transition in the form of creative destruction of the print media, which was severely affected by the 2008 crisis. “Nothing will work”, concluded Shirky, in regard to the restructuring of print media, the organizational forms of the industrial age are inevitably replaced by forms adapted to digital data. His book Cognitive Surplus: Creativity and Generosity in a Connected Age [SHI 10] is a positive assessment of collaborative economy: individuals use their free time a little better by becoming active creators and engaging in new forms of collaboration. Only a tiny fraction of leisure time now results in creation, but this time was previously devoted to passive consumption of television programs. The world therefore tends, according to Clay Shirky, to become better, even if certain organizational forms cannot be maintained.

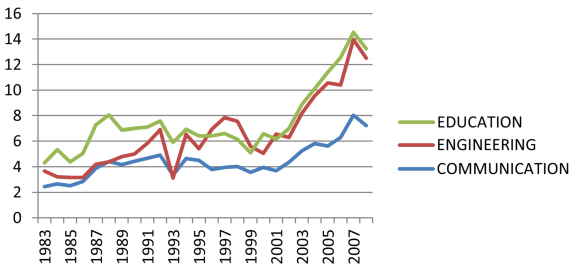

The statistics presented by the International Labor Organization show the relative evolution of earnings according to occupational group. Since 1985, airline pilots have always experienced an advantageous change in their salary, measured by a global index expressed in purchasing power parity, while the same index changes little for seafarers in offshore fisheries, hit by the collapse of fish stock due to overfishing, as was the case in Newfoundland in 1992. Among the occupational groups in the cultural and creative activity sectors, the overall average hourly salary is the least dynamic for communication skills. On the contrary, a positive development is observed for the remuneration of engineering professions in creative activities (see Figure 3.7). Among the media, radio-television performed well, but not the daily press. Journalists of the print media, performed well, but not the daily press. Journalists of the print media, seem fairly general in the world.

Figure 3.6. Overall average hourly wage in creative activities

(source: OIT)

Changes in the daily press for the period after the 2008 crisis are in line with Clay Shirky’s prediction. The dramatic fall in sales and advertising resources for the print press is continuing in most countries, as they are moving to new digital entities. A small group, Schibsted, the local Norwegian press, is a good example of a strategy firm with a little more anticipation, while most press groups remain very stubborn in their defense of paper mediums. The Schibsted group first developed the free formula (title “20 minutes”), then the peer-to-peer (“Le bon coin”) websites based on the Taobao model, which did not expand outside China. In Europe in 2011, the bankruptcy of printed newspaper advertisements led to the dismantling of local French news group, Hersant.

It is a technological transition that corresponds to patterns found in similar episodes. The growth of “pure players”, blogs or sites like Médiapart created in 2008, is in line with Clay Shirky’s prediction as they are new organizational forms asserting themselves.

The organizational forms of the daily press can be traced back to the industrial period and to the boss Emile de Girardin. He invented the business plan “biface” (readers and advertisers). Commercial advertising revenues lower the selling price per unit of the newspaper and thus reach a very wide audience. This “biface” formula was taken up by Net giants, and thus the daily press is also a victim of a mode of organization close to pure players, but with a communicating vase effect: a dramatic decline in sales and advertising revenue is simultaneous in the daily press, while audiences and these same advertising revenues are transferred to digital media.

From observation, globalization uses organizational forms invented during industrialization, and organizations of the industrial era exhibit organizational similarities that may be more severely affected by a technological transition, another organizational peculiarity in the field of the daily press, the news agency, which prefigures the collaborative economy. News agencies have subscriptions that come from professionals. They collect local information, work on it and send it to newspapers. This system is now widespread in wiki applications, such as the Cochrane Collaboration or Wikipedia.

3.4.2. Collaborative economics and the dynamics of civic spirit

The 2004 tsunami in the Indian Ocean resulted in an increase in generosity, which was also reflected in the growing number of humanitarian organizations, with a certain similarity with the intensification of companies by young enterprises carried out on the Net. Collaborative economics is an attempt to theorize this sensitive civic boost in most forms of organizations. The political party is also an organizational form, and Civic dynamics claimed by the collaborative economy are found to explain phenomena that seem to reinforce it, like the Arab Spring, but also unexpected setbacks, such as the election of Donald Trump as President of the United States.

Promoters of the collaborative economy argue on the civic aspect of new economics, forms from transition technologies based on active consumer behaviors, within which the consumer is both a transmitter and receiver, replacing technologies based on the passive consumption of a message delivered by one or more transmitters. The technological transition of the arts and culture is that which goes from the radio–television and its passive reception by consumers toward a creative activity in Internet Networks. However, activities related to radio–television still predominate today in the statistical world of culture and creative activities, according to UNESCO nomenclature.

Three types of civic spirit and culture dynamics are proposed in different veins of literature on globalization. The outlook is either downward, rising, or a cycle of civic aspirations.

Bearish literature dates back to Tocqueville. Democracy does not necessarily guarantee quality. The democratic procedure will be based on the taste of a median consumer, which generates a strong repulsion in the theorists and an elitist perception of culture. Industrialization, for example the manufacture of cotton fabrics, created a “loss of aura”: cotton garments were highly prized by the upper classes at the end of 18th Century and were highly priced. Industrialization led to cotton fabrics that became cheap and widely used as work clothes. The massification of the object led to a loss of aura, and this Tocquevillian theme would be taken up by Walter Benjamin in a famous essay on photography [BEN 39].

According to Tocqueville’s notion, the structure of preferences is not modified by learning, a drop in quality is a direct result of a collective choice procedure. Industries have implemented quality procedures, and contemporary arts have often re-established a positive status for banality, so that criticism strictly conforming to the Tocquevillian type is amended in a literature of “the society of the spectacle” with eponymous work dating back to the 1960s [DEB 67]. A more recent synthesis is proposed by the Peruvian Mario Vargas Llosa [VAR 15]. The commercial offer favors comfort and contributes to negative learning, leading to frivolity and a “degradation of culture and spirit” [VAR 15, p. 180]. Such highly rated artists, such as a television show host, can easily illustrate bearish conjecture.

The question of measuring the quality of culture was raised by Thomas Mann in 1914, in which it was asked where to classify a civilization such as the Aztec culture with its human slaughter and cannibalism? From the debate between Culture and Civilization which followed, Norbert Elias’ approach was retained and used, linking this level of culture or civilization to better self-control, quality to social relations and the reduction of social violence [ELI 75]. Peru only abolished the legal trade of severed heads in 1959, while homicide remained the leading cause of death in adult males in several Peruvian regions. Today, after the Shining Path civil war in 1980s, Peru has a much lower level of social violence. The period of globalization therefore corresponds rather to an increase in major cultural indicators, as long as one does not base oneself on the subjective impression of stupidity in front of a local television program or before a few works in a contemporary art exhibition. The conservative discourse of Vargas Llosa values traditional transgressions, such as bullfights. While the innovation rate in new Peruvian firms has one of the lowest values in the world rankings, we can clasify the Peruvian economy in a factor economy, in this case, as the world’s largest producer of cocaine.

The second prospective hypothesis is that presented by Ingelhart. Materialism has only one time, and postmaterialism follows. The World Value Survey periodically renews a map of the major cultural areas in the world, noting their respective developments. The Triad consists of the most important areas for innovation (Asia-Pacific, Europe and North America). The least favorable areas for innovation are also subregions of several cultural area as; quite close to the center of the Inglehart cultural map. In the sample studies of GEM countries, the countries with the lowest innovation rate among the new firms are divided into three cultural areas: Brazil and Peru and other small countries of Central America, Russia and some other countries of Central and South-East Asia (Malaysia) and some African countries or those on the Arabian Peninsula such as Algeria whose economy relies almost exclusively on a single natural resource. Globalization focuses on the organization of large economic movements, however the delimitation of cultural areas rarely moves. Factor economies only form a mosaic of scattered countries, highly specialized in exporting an abundant natural resource, and having no truly salient features: they are neither the most traditionalist nor the most individualistic, nor are they the most successful in economic survival.

Figure 3.7. Structures of the economy in Inglehart’s cultural map

Neither on the strong side of innovation, nor in its absence, is there a kind of specialization of cultural areas. More than explanations of the cultural type, it is economic policy choices that explain why different cultures are either factor economies or economies of innovation. A step-by-step explanation does not work: it is not just one side of the world that is surviving and is in search of material growth, but there are more intellectual issues that arise when the standard of living exceeds a certain threshold. Economically traditional zones are marked by an enrollment in global flows that involve a large volume of natural resources or labor. The undeniable civil push of the Arab Spring has been met with many difficulties. However, the important role of social networks has been consistent; confirming the hypothesis that there is a link between collaborative economy and a positive civic dynamic.

A final approach of civic dynamics is that of a cycle. Hirschman introduced a cycle based on the alternation of aspirations to private happiness and civic engagement. These cycles have a rather national scope, and therefore may be not synchronous in all parts of the world. This cycle has been translated into a system of alternation of two ruling parties, or in a rather regular succession the political crises whose pace maintains a distant link with, for example, climatic instability as is the case in the Sahelian zones [ABB 14].

3.5. An economy of remoteness

A single psychic distance was the foundation of the Uppsala paradigm. C.A.G.E.T. literature (cultural, administrative, geographical, economic and technological distances) reformed this approach: it is necessary to adapt the different dimensions and adapt to each one. Promoters of the global organization put forward a slogan of simplicity, in a context where activities upstream of the product cycle more often than not require proximity, while the market is global.

The positive effects of proximity have attracted more attention than remoteness or a combination of the two. The demand for a systematic use of remoteness in the classical European era [PAV 96] is undoubtedly to be mitigated, more verified in the Grand Siècle in the performing arts than in a Caravaggio painting, seeking instead to bring works closer together in daily life. The disappearance of a wonderful “distant close” is deplored in the literature of “loss of aura” in the tradition of Tocqueville and Walter Benjamin. The conceptualization economy of remoteness thus remains too summative: remoteness would have changed from an algebraic sign in an earlier period and it would have been necessary to add from the distant to increase the value, while starting from industrialization, this distant added would come to be subtracted from the value. Even in cave art and Paleolithic crafts, the question economy of distance was already posed. Glacial age societies had both short-distance and long-distance relationships, particularly for marital strategies. Some imaginaries are linked to commensality: representations of cave bears are vivid and sometimes even bear traces of animal claws, as in the cave Chauvet Pont d’Arc. In other imaginaries, as in Lascaux, close elements are composed in a magical way.

3.5.1. Birth of the unicorn

For the Aurignacian and Gravettian periods, animal representations corresponded well to the local megafauna of the time. For Lascaux, megafauna representations undoubtedly include animals that had existed more in the south, beyond the Pyrenees, the period being a glacial maximum. The enigmatic figure commonly called “the unicorn” on the left wall of the “salle des Taureaux” is composed of two of the most common animals found in the periglacial zones, the rhinoceros (Coelodonta antiquitatis) and the butterfly (Parnassius Apollo). The heavy rhinoceros has the antennae and aureoles of a butterfly present today in Scandinavia and in the mountains. The banal scene, a summary of a very cold climate, takes on a magical dimension, and fits into an Elsewhere of the wildlife representations of Lascaux..

For the men of the European Grand Siècle, proximity was religious, with Caravaggio painting Gospel in a daily setting, while unreality and infidelity were intentional in all artistic arts and crafts. Here on earth is the celestial homeland, and society is only possible in close proximity to God, or else rejected in social, historical or geographical distances [PAV 96].

The economy of remoteness that brought the birth of the unicorn is a marvelous otherworldliness where a loved one finds themselves transformed in a magical extravaganza. Keeping cows beyond the mountains by a unicorn keeps a fantastic otherworldliness accessible. In great Paleolithic sites, the animal series is sometimes weakened by Omega, from the last in the list, as is the case in Lascaux. This last in the list is a composition from nearby elements, a hallucinatory summary of the biotope. The original definition of the unicorn results from the operation of distancing from the near.

The initial theory [PAV 96] is a simple opposition between a contemporary era when the intraworld is overvalued, and a classical era where, above all, the distant gives value. It is probably possible to develop an economy of remoteness, starting from combinations in the imaginary near and far. A first economy of remoteness comes from an extreme cold climate, while resources are lost in diversity and quantity. An imaginary variety is conveyed by myths and wonderful tales, in which unicorns have been peddled for a very long time. Historical periods and epochs of Reason were succeeded by those of competition of maritime civilizations, with a new economy of remoteness, where proximity remains very highly valued since there it is now a new religious one.

3.5.2. The benefits of remoteness

Evangelista [EVA 05] indicates that a local market is often less accessible than an international market: the local market can be very small, or very competitive, and the entrepreneur may encounter hostility from local authorities. The phenomenon of congestion and surging real estate prices have led to the promoter of the theory of “creative class”, Richard Florida [FLO 17a], to advocate urban policies aimed at avoiding the capture of wealth created by property owners. The same recommendation is made based on an analysis of the situation in Silicon Valley and the urban area of San Francisco [VIC 16, p. 101]. A table of contributions of remoteness can be drawn from experience clusters and competitiveness clusters [VIC 16, p. 56]: “A close proximity generates conformism and can stifle the capacity for innovation. Strong organizational proximity can lead to bureaucratic rigidities. The same is very true for the social embedding of innovations, within which, it promotes trust, leading in turn to a lack of openness towards other actors. Finally, having a very close institutional proximity (causes) locking effects which block new technological dynamics” (see Table 3.1).

Table 3.1. Contributions of remoteness

| Distance | Too much proximity leads to… | Contribution of remoteness |

| Cultural | Conformity | Existence of otherworldliness, support for non-conformism |

| Administrative | Bureaucratic rigidity, vulnerability to regulatory change | Reduction in vulnerability |

| Geographical | Lack of openness outside a territory | Construction of an international reputation as a refuge for quality |

| Economic | Lack of social openness | New markets |

| Technological | Institutional lock | Simplicity |

Porter’s recommendations on competitive clusters in the 1990s were part of an intellectual lineage dating back to the industrial Marshall districts. The aim was to intensify interindustrial relations by focusing on the internal relations of member organizations of competitiveness clusters and not the markets as a whole. In a succession of paradigms, born global organizations bring about a reform of Porter’s approach. They introduce the benefits of remoteness: that otherworldliness facilitates non-conformism, reduces vulnerability, builds an international reputation, expands into new markets, and simplifies broad access to innovation.