Introduction

The Birth of Art

The purpose of this work is to discuss the importance of the transformations in innovation systems brought about by globalization. We understand this term as the existence of new macroeconomic solidarities. These have been problematized since the mid-1980s, with Kenichi Ohmae’s assessment of a tripolar world [OHM 85].

However, global macroeconomic solidarities have existed for a very long time. Thus, multiple responses have been offered to the question of when globalization began. The academic debates in economic history put forth a date of origin, either that of the complete coverage of the globe by maritime routes [FLY 04] or that of the start of economic integration throughout the 19th Century [BÉN 08]. Other specialists are interested in the relationships between anatomically modern humans and their environment, and they introduce a caesura that is major in their eyes: that of the birth of the arts [FLO 17b]. The presence of anatomically modern humans in Western Europe is attested by a fossil in a cave in Kent, which dates back to between 44 and 41 kyr (44,000–41,000 years before the present day). The first globalization is that of a terrestrial expanse that spreads anatomically modern humans across every imaginable environment, from Australia to the Arctic Circle. Then came maritime expansion, the Industrial Revolution and contemporary globalization: however, since the first terrestrial expansion, the question of innovation has been asked, because global occupation is only possible because of the discovery of new methods of life that are appropriate for very different environments.

The birth of the arts was thus given its rhythm by successive globalizations and fragmentations. In the 19th Century, the Mediterranean civilization of antiquity was like the cradle of the arts, already associating defragmentation or globalization and birth of the muses. The popular list of the arts generally distinguishes classical arts (architecture, sculpture, graphic arts, music, literature and poetry) and modern arts (those since the invention of photography), thereby setting arts whose invention dates back to the Paleolithic period against those introduced very recently in terms of the history of humanity. Due to this double birth, some approaches will focus on the contemporary aspects and cloud the consideration of origins, as was the case of Theodor Adorno’s theory of esthetics [ADO 70]; others, on the other hand, will first question the oldest period, like Georges Bataille shortly after the discovery of the Lascaux cave [BAT 55]. Why art? For contemporary specialists in prehistory, the responses run in two different directions, either referring to cultural evolutionism, a progressive awakening on the occasion of environmental modifications or a history of beliefs and rites in the tradition of Mircea Eliade [ELI 64], which leads to the formulation of a hypothesis associating the translation toward the upper Paleolithic and a spiritualization of the environment [ELI 74].

Cultural evolutionism could provide a reassuring message: the shocks from modifications to the environment lead to innovations. There could be an automatic mechanism associating climatic volatility and innovation. The periods that form critical times for the formation of the arts are those with the maximum climatic instability; it is therefore necessary to explore this first hypothesis.

I.1. Climatic instability and innovation

The birth of the classical arts (music, dance, fine arts and decorative arts) can be presented in two phases with an intermediary “leap”. This “leap” took place in the Late Pleistocene (120 to 11.7 kyr), around 45–35 kyr. The Late Pleistocene period was marked by strong climatic instability, more significant volatility than in the warmer period that followed it, the Holocene (starting at 11.7 kyr).

Schematically following a long “ocher age” was the period of territorial expansion for anatomically modern humans, where a procession of the arts is attested. The populations of different human groups are low, with a probable regrowth of the anatomically modern human populations around 50 ka, whereas Eurasia had seen the growth of the Neanderthals in the previous period. One of the longest known sequences of anatomically modern humans occupying a site can be found in the extreme south of the African continent. The Blombos Cave and the Klipdrift Shelter were used between 108 and 59 kyr [ROB 16]. The ocher age started long before any climatic disturbance in Blombos. The so-called “Still Bay” is that of the “stamps”, blocks of engraved ocher most likely used for body paintings and sophisticated tools made of up bones. The apogee of the series of cultures on the site can be found between the primary climate change and after the response of adapting subsistence policies. The following period, 66–59 kyr, known as “Howiesons Poort”, marked a clear step backwards. Technologies remained stable while the environment was constantly instable [ROB 16]. These two periods include the probable demographic minimum of the modern human species after a mega-catastrophe dating back 72 kyr.

Figure I.1. The ocher age and climatic instability, distance in km from sea sites

(source: [ROB 16])

The period of the “Howiensons Poort” culture is characterized by the presence of ostrich eggs engraved through another very long series, that of the Diepkloof shelter site [TEX 12]. Between 65 kyr and 55 kyr, these eggs were engraved with the same design, made up of hatchwork at a right angle with two most likely circular strokes. The ostrich eggs would contain around 1 L and were used as gourds. This use already seemed to be that of these engraved eggs, some pieces of which formed a mouthpiece.

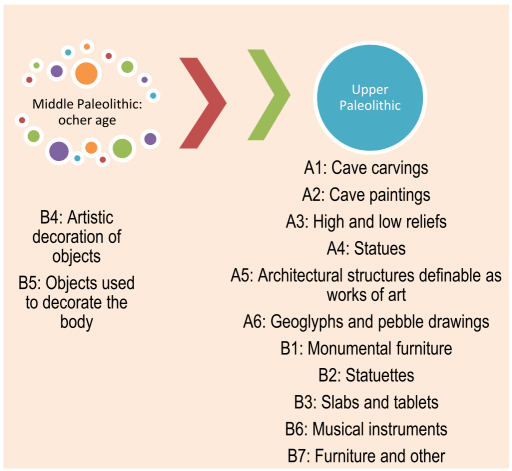

Creative activities can be divided into “portable” and “immobile”. Art from the upper Paleolithic was particularly known for being wall and cave art, thus “immobile”. The ocher age stands primarily by “portable” creative activities: jewelry including necklaces, body paints, tools and ostrich eggs were decorated with geometric figures. Anati proposed a 13-item nomenclature for prehistoric and tribal art [ANA 03]; the ocher age is limited to two of these items (artistic decorations and jewelry), all of which were used in the period of the birth of the arts.

Figure I.2. Birth of the types of prehistoric art according to Anati’s nomenclature

The early days of Middle Paleolithic art also differed according to the importance of the necessary training. Graphic expression remained very limited in all production found in Blombos, contrary to that from the Aurignacians in Eurasia or the “Apollo 11” cave site in Africa. Musical instruments, like the eight flutes from the Aurignacian sites of Swabian Jura imply training for both their creation and use [FLO 17b]. The start of great immobile art has been dated back 39.9 kyr in Indonesia and 37 kyr in Europe (Castanet shelter); the dates obtained in Africa and Australia are approximately 29 kyr. A study by Helen Anderson [AND 12] indicated a training experience, drawings stemming from a relationship to an element of the environment, thus this would have to be figurative art. This does not explain why these carvings appear, however.

The level of technology reached around 100 kyr in Blombos included carefully made spikes for hunting and the preparation of colored mixtures with pigments [ROB 16]. This level of technology would then decline only to be fully recovered at the end of the glacial period, e.g. with the Lascaux hunters from the last glacial maximum. The small size of the human groups could be an explanation for this decline phenomenon: explorers in the Pacific Islands found themselves face to face with very small populations that had conserved beliefs and cultural objects indicating past experience with dug-out canoes, while this had disappeared due to a rupture in the remission of the know-how necessary for naval construction. Work in genetics indicates the probable presence of a “bottleneck”, a disappearance of a large part of the anatomically modern human population due to a mega-catastrophe. The total population of anatomically modern humans had dropped to around 15,000 people, reducing genetic diversity. The date proposed for this minimum level of human demographics is around 72 kyr, with the coldest oscillation for the southern hemisphere and the explosion of the supervolcano Toba located on the Equator coming together. The period of engraved eggs from the Diepkloof shelter corresponds to a warm climatic rebound in the southern hemisphere around 60 kyr.

Another simultaneous occurrence between the explosion of a supervolcano and an extreme cold took place around 39 kyr in the northern hemisphere. On a site located on the Don River in modernday Ukraine, Kostienski, cultures were maintained and later development was more significant. Thus, three kinds of relationships between the large-scale climatic and geological risk and human cultures can be demonstrated in these scenarios. A scenario of resilience for the event of 39 kyr, a scenario of disappearance for that of 72 kyr and a simple procyclic climatic relationship for the engraved eggs around 60 kyr: it became warmer, decorated ostrich eggs that served as gourds were found in large numbers with a simple decoration identically produced, as if “industrially”.

In the northern hemisphere, Neanderthals occupied modern-day Europe and participated in the ocher age, as did anatomically modern humans originating in Africa. Before the event from 72 kyr, the Neanderthal population spread to the Middle East and Central Asia. The two human groups first established contact in the Levant. The period from 72 kyr to 57 kyr indicates the development of a proper Neanderthal culture with the appearance of individual tombs and funeral offerings. The great climatic instability of the period led to the disappearance of Neanderthal groups whose trace was lost after the event from 39 ka. Gene sequencing indicates hybridization between Neanderthals and anatomically modern humans starting with asymmetric interfecundity [CON 16]. Intermixing took place during the spread of genetically modern men across Eurasia.

One characteristic of the Paleolithic innovation regime was felt by historian of religion Mircea Eliade, who, in particular, detailed a mythology of the egg [ELI 64, pp. 347–349]. Eliade concluded “spiritual creativity”, whereas he indicated the quasi-absence of progress on the technological level, this being nearly equal at the start and finish of this glacial period. The explanation put forth is that of ruptures in the transmission of technological expertise caused by the very low populations of human groups during this entire period. The genetic data lead to the belief in a great loss of variety due to the “bottleneck” from 72 ka, and the hybridization of a single species results from the different human groups during the great dispersion of anatomically modern humans. A fortiori, a very reduced total human population can only lead to a decrease in cultural variety. This spiritual creativity was also present in human groups that have disappeared, like the Neanderthals [CLO 11]. After the event from 72 ka, individual tombs appeared in Europe, though this was only populated by the Neanderthals [CON 16].

Figure I.3. The birth of the arts in light of Descola’s anthropology

Philippe Descola offered a schema of these ontologies according to four primary types [DES 06]. This theoretical framework is based on the existence or inexistence of a single interiority, or a single physicality between Man and the environment. Certain forms of totemism are associated with body painting: for the Burned Crocodile clan, the entire body must be painted with colored scales. The blocks would be an appropriate technology for this make-up problem. An absence of differentiation of interiorities and physicalities posed the practical problem of reproducing the outer appearances of animals on one’s own skin. The material found in the Blombos Cave seemed well adapted to this type of ontology: there are different figures on the blocks, and thus all the tools for this ontological totemism as defined by Descola. Descola’s typology is proposed using ethnographic data, i.e. such a theory of being could likely have survived, or reappear, after the tragic episode of the “bottleneck” of 72 kyr. The explosion of body painting is that of ancestral spirits, and a rigorous code governs the use of marker blocks [DEL 07a]. The ethnographic data specifies that ontological totemism is a golden age of markers, with extremely rigorous intellectual property.

The two transition episodes from Descola’s schema can be brought together through the events of 72 kyr and 39 kyr. First, this would be the start of understanding the complexity of an environment – the physicalities become different, animated by a creation process. Then, differences would be introduced among the spirits residing within the interiorities, and this would correspond to the episode of the birth of the arts. If this birth were reproduced at the first of these shocks, i.e. 72 kyr, we would have been in a scenario where anatomically modern humans having experienced the worst disaster of their demographic history would have turned toward awareness of the environment. We would have had a naturalist genesis of the arts. This is not the case. The episode of the engraved eggs dates back to approximately 65–55 kyr during a period of global warming occurring after expanded comprehension of the environment and before the differences made between the spirits inhabiting equivalent carnal envelopes. For example, in the Aurignacian cave at Chauvet Pont d’Arc, there is a representation of a battle between two rhinoceros, one with hooves, the other without, possibly a familiar spirit. This figure summarizes the accomplishment of two phases: first, the specificities of the physical appearances are captured in a very realistic and precise representation of the rhinoceros, and second, a lesson is made insistent concerning the different types of spirits that inhabit the fauna.

“An epiphany of creation, a summary of cosmogony”: thus was characterized Mircea Eliade’s mythology of the egg [ELI 64, p. 349]. A hydria decoration with a circular geometric motif associates a universal vital stimulant, water, with multiple forms of life. The primordial act of creation is repeated in a very simple way through the use of the gourd. Some genealogical markers from the totemism period make space for differentiated beings revitalized by a single vital force.

Ensuring the recreation of the act of creation will receive a different translation during the first realizations of wall and cave art. First of all, the creation myths used become varied: one of the very first representations (Maros Cave, in modern-day Indonesia) is that of a babirusa above a line of ground – most likely related to a regional tradition (Asia, North America) of a myth where a diving animal resurfaces from the primordial waters carrying the bit of earth that will give birth to the terrestrial world, while the sites in the Great North of Siberia refer to a couple of primordial twin gods, and the painted caves from the Cantabria region of France evoke Creation through an emergence site. This great variety of major myths associated with the birth of the arts in very distant geographic locations allows us to discard the hypothesis of spreading and preserving an initial, very structured foundation of myths. The foundation has been greatly added to in this episode of spreading, e.g. this myth of the Diver, which most likely originated in China. All of the large kinds of creation myths are represented through all of these first artistic manifestations. The babirusa from the Maros Cave (south of the Indonesian island Sulawesi) could date back to 35.4 kyr, while a negative hand could be even older (39.9 kyr) [AUB 14]. This same kind of negative hand can be found in Aurignacian art in Europe, given that these representations disappear during the last glacial maximum.

Second, if the convergence toward a unique amalgamated myth does not take place, it converges instead toward a certain type of intercession with environmental powers with a shamanistic character. For Siberian sites, the practices of hunter–gatherer societies stick to this type of religious organization. As for the Diver myth, the use of animal familiars, which lies at the heart of this mythological drama, is associated with a shamanistic practice. This is also documented in Africa and Australia, in connection with the development of the arts. The decorated caves in Europe are also most likely connected to shamanistic conceptions [CLO 11]. Wall and cave art are known for the ice age in every part of the world that can be accessed without sophisticated navigational means. “All the indications point toward a shamanistic religion, the basic concepts of which are the permeability of the world(s) and fluidity” [CLO, p. 266].

Why art? And what relationship with the strong climatic instability of its genesis period? Very summative responses to these questions must be discarded: it is pointless to rely on an automatic innovation bonus that would come as compensation for climatic instability. With relatively small human groups, this instability sometimes leads to extreme reductions in populations and know-how. In the chain that moves from creativity to innovation, human groups from the Middle Paleolithic are proof of spiritual creativity resulting in the creation of a resilient cultural foundation. A “good cultural formula” is the condition for the ubiquitous spreading marking the transition to the Upper Paleolithic. This context of great creativity and technological stagnation brings about the birth of the arts.

Great climatic volatility does not directly create human cultures. Most of the time, these “go through” climatic crises with a wide range of minor adaptations, but sometimes they make leaps. Based on a theoretical framework put forth by Philippe Descola, two important modifications took place in the Paleolithic for anatomically modern humans:

- – the transition from a system of identifying the elements of the environment through a very meaningful and very reductive totemic grid to one where objects are much more finely characterized. For example, the “egg culture” after the return of a warm climate in 60 kyr is one where a universal creation process exists;

- – the shamanistic hypothesis would constitute the second leap, that of transitioning toward the Upper Paleolithic. Different types of spirits inhabit beings. The creation myths multiply and diversify. The pedagogy of wall art deals with the powers of nature, the beliefs in the processes that create beings, and the subtleties existing between the different types of beings that are present with the same physical appearance.

I.2. “Leisure class” interpretations

The “leisure class” interpretation was initiated by a work by Veblen [VEB 99]. It was renewed by Bataille after the discovery of the Lascaux Cave [BAT 55]. Veblen’s analyses and then Bataille’s were formulated using the knowledge of their times on the evolution of Man. A new formulation has been proposed today by urbanist Richard Florida [FLO 11]. The propositions advanced in these approaches by the leisure class are those of the pertinence of sociology of the social leisure class opposing industrial and idle classes and that of an approach in terms of social structure evolution. The leisure class, despite its unproductive character, would contribute innovation or determine economic stagnation.

I.2.1. Veblen and conspicuous consumption

Veblen’s initial approach introduced art and creativity through a private demand for conspicuous consumption by an idle part of society. The technocratic current from Veblen’s work promotes the mechanization and managing role of production engineers. Ruskin saw both material abundance and artistic poverty in industrialization. Veblen’s puritan critique focuses on a concern to appear and squander; it can accompany a development of functionalism in the arts, a movement that historically appeared in Chicago after the release of his work on The Theory of the Leisure Class [VEB 99]. One of the examples Veblen gives of the “leisure class” is pre-Meiji era Japanese society. This is therefore a discourse encouraging industrial modernization based on the critique of the private request for prestigious and luxury goods. The anthropological argumentation is focused on the episode of crystallizing social integrities after the major innovations of the wheel, steel and writing. He summarizes three steps: first, a peaceful agrarian society, then barbarians living from pillage and plunder and finally a stratified society where an elite remains the heir to peaceful and bellicose temperaments from previous eras. Concerned with appearances, this elite will promote esthetic canons adopted by the entire society due to the signs of social preeminence.

Later texts from Veblen explain his social evolutionary theory, encouraging new habits through new institutions. Mercantilism, physiocracy and technocracy share the fact that they only conceive of a creative social status for a productive class: merchants, farmers and industrial organizers, respectively. Before Mary Pickford, the first true Hollywood star, the remuneration and social organization for the first silent cinema actors was based on that of the Taylorian scientific management industries. The creative, like everyone, was highlighted in new habits: a large industry.

Veblen’s conceptions imply an unlimited exogenous source of abundance: the theoretical explanation is focused on social processes for spreading the arts, existing innovations and productive processes for mass production, without asking how these arts and innovations came about. There is a benevolent hidden demiurge who provides endless prosperity and progress behind the scenes.

I.2.2. Bataille’s birth of art

Georges Bataille proposed a new declination of the leisure class in his work on “Lascaux, or the Birth of Art” [BAT 55]. His work on The Accursed Share introduced wasteful generosity for a world flooded with an overabundance of energy. The succession of the tool, then of art is seen through the arrival of the “creator of art at the source of humanity today” [BAT 79, p. 355] in groups of Neanderthals. This intermediary group, Neanderthals, disappeared, leaving only completed humanity.

The creative changed classes between Veblen and Bataille: for Veblen, a mass-marketed profane art is produced by working-class artists, as with the beginnings of Hollywood. For Bataille, the creative are in the leisure class: a full, festive humanity replaces an initial stage of humanity attached to tools.

Bataille recognizes spirituality in anatomically modern humans, but not in Neanderthals, in accordance with the archaeological knowledge of the time, that of the Breuil-Benoît Abbey. This hierarchization no longer exists today due to archaeological evidence of the Neanderthals’ cult and cultural concerns [CON 16, CLO 11]. Bataille’s work initiates an exploratory process, however. The popular position of prehistorians from the times, that of “hunting magic”, is no longer tenable after Lascaux: “The reality that these paintings describe singularly exceeds the material search for food through the technical means of magic” [BAT 79, p. 373]. The hypothesis of a transition toward a sacrificial religion at the time of the leap between the cultures of the Middle Paleolithic and the Upper Paleolithic can no longer be defended: “Paleolithic humans did not reach the point of using sacrifices” [BAT 79, p. 373]. The hypothesis of shamanic religion, non-sacrificial hunting religion, provided a synthetic positive formulation to Bataille’s different conclusions.

The text on Lascaux makes references to Huizinga’s work on Homo ludens [HUI 51]. “What art is, first and foremost, and what it remains, above all else, is a game” [BAT 55]. The game is not included in Bataille’s work, as a set of rules for the game, a social codification of strategies. The game is “what links the meaning of Man to that of art, what delivers us, if only for a short while each time, from the depressing need, and somehow brings us into that marvelous explosion of richness for which each of us feels he or she was born” [BAT 55].

However, “nothing proves that the game has reduced humanity” [BAT 55] before, that is to say, Bataille is sensitive to the weakness of his schema making a playful humanity succeed laborious creatures. The current data deny this succession from a leisure society to one of pure labor; 100,000 years ago, the humans from the Blombos Cave had a stunning view of a magnificent bay, abundant self-service food, and they were primarily concerned with their jewelry. Approximately 45,000 years before the present day, these same anatomically modern humans basked in the polar night in company of giant megafauna, most often impossible to hunt. Leisure class approaches only offer a schema where part of leisure arises from an initial total constraint of labor, whereas an initial leisure situation seems better adapted to the empirically proven evidence from archaeological exploration.

I.2.3. Florida’s creative megalopolis

Urbanist Richard Florida proposes a new variant of the leisure class schema. Florida [FLO 02, p. 67] revisits Veblen’s idea of a change stemming from a process of cultural transformation motivated by engineers or creators. He briefly outlines a “creative class”, bringing together all careers that do not involve agriculture, industry and service. From this statistical dichotomy, Florida draws a correlation between this creative class and the economic growth of cities. First, he deduces from this the urban authorities’ policy of attracting talents, then of policies providing social accommodation in its most recent contributions. Florida explains the diversity of its recommendations through a will to respond to different urban crises. The theoretical framework of the “creative class” is not overly restrictive, and it subsists, accompanying urban policies attempting to head toward the margin of complex processes. In the 1970s, the problems faced by cities arose from the deterioration and abandonment of central spaces, due to a redefinition of economic uses. Florida speaks of the “donut” city, a city whose hypercenter has lost all positive functionality. The reference situation for Florida after the 2008 housing crisis became that of stagnating medium-sized cities, with problems of housing price and lease instability in downtown areas, and tensions between the urban authorities and private developers and space planners. The evolution of contexts can be summarized through a dynamic of gentrification: in an initial phase, a tolerance of the urban authorities to bohemian and gay areas allowed for a progressive reappropriation of urban centers by the wealthy. However, the dynamics of gentrification can go too far, even if a middle class is once again chased out of the cities by price increases caused by very rich people. Excessive gentrification leads to the disappearance of the sought-after creative atmosphere and the restriction of possibilities for creative talents to live in downtown areas.

In Florida’s eyes, innovation policies present an overly technological orientation. He thus emphasizes the maintenance of a creative urban atmosphere, based on Talent and Tolerance, as well as Technology. The city is meant to be the fusion site of the different components that could lead from creativity to innovation. Florida proposes an attractivity policy implemented by urban authorities, supported by public authorities and focused on talents from an offer of urban cultural amenities. These cultural and social policies address people and not organizations (companies, universities, educational centers), as innovation policies and their different formulas for technological parks generally do.

Florida proposed a sociological interpretation of contemporary globalization, which he explains through the emergence of a creative class. He defended a theory in which social stratification is more important than the distant effects of globalization. These are the proximity relationships between talents of different specialties that could explain the economic dynamism of large cities. The proposed policies aim to concentrate resources in large urban sites. In the most recent contributions, he adds that targeted social policies are necessary to avoid appropriation by localized positive externalities [FLO 17a]. In relation to globalization theories like that of Kenichi Ohmae [OHM 85], where it is businesses that diversify their spatial strategies in the world and where States are asked for a simplification effort, Florida introduces new public actors, namely the large urban metropolises of rich and emerging nations. These are entities that differ little in terms of an attractivity policy from those suggested by Ohmae, himself an advocate of simplifying the world’s administrative map through modest subregional entities. Although the United Nations’ statistical system includes 32 large regions around the world, Florida establishes a map of the world using satellite images, limited to 40 megalopolises of economic significance around the world. An old sociological tradition, that of Comtian positivism from the 19th Century, made no distinction between socialization and urbanization. Inhabitants of the country become civilized by going to live in cities, in the positivist sociological tradition: for Florida, humans develop their natural creative potential in a context of great urban density by having more numerous interactions, stimulating creative results and finally innovation.

However, in the conclusions of the city monographs that he created, Florida must concede that the consequences and effects of training remain limited based on this theoretical schema of an urban creative melting pot. The very rich are not specifically attracted by cultural amenities, and they are concentrated in megalopolises gathering decision centers. The most creative countries are also the most egalitarian. The forms of salary remuneration contribute to this situation of equality, whereas non-salary earnings lie at the heart of contemporary urban crises [FLO 17a]. The attractivity policies recommended by Florida appear to be focused on location criteria in empirical studies on the preferences of the creative in terms of localization. The creation and cultural professionals choose a location based on the proximity of their family and friends, their places of education, employment opportunities, then natural amenities and only then leisure facilities. Studies on European cities show that the creativity lies at the origin of the city in question, always in majority proportions. Only a small complement comes from other regions. The city appears above all else as a decisional center, an environment of public space and risk management. The places of creation, invention and innovation do not specifically seem to be linked spontaneously to an urban centrality, and the intervention of public policies is necessary to have a will for territorial fixation in decisional centers.

In his successive formulations, the urban policies of Richard Florida’s “creative city” provide information on strategies implemented by metropolis managers in Europe and North America. Their variant can be both elitist, through the attractivity of the best talent, or more democratic. These policies remain limited to the middle classes and urban superiors. This always involves policies focused on the heart of the city, targeting the resident populations in central locations. Richard Florida’s most recent works [FLO 17a] introduce a concern regarding disproportionate spatial inequalities. When the analysis framework is erased by the leisure class, the analyses become more pertinent. Thus, Veblen and Bataille’s approaches have only retained conspicuous consumption and the birth of the arts.

The hypothesis of an initial, brilliant party at the source of the first works and a full innovation capacity does not seem to be confirmed as well by the archaeological approaches as by the studies on creative melting pots. New constraints arising from hydroclimatic instability or the historic conditions of distant travel provide more of a situation of very heavy constraints. The Manilla Galleon, which some historians consider to be a symbol of the start of globalization, often returned with no living souls, everyone having died of starvation or illness while crossing the Pacific non-stop. Another example is of a ghost ship returning from the China Sea, with treasures hidden under dead bodies; this entrance to globalization now swaying to the gloomy side.

I.3. The Manila Galleon

The Manila Galleon in Acapulco established the first regular transpacific maritime trade route. This maritime connection existed from approximately 1571 to 1815. It crystallized discussions in economic history on the existence (or lack thereof) of several stages of globalization. Many analyses only accept one stage, an initial “big bang” of globalization, but the dates set forth vary greatly. Economists are only concerned by the contemporary phenomena of globalization, which only become the object of study around the mid-1980s. Historians are not in the same mindset, instead referring to a much earlier “big bang”, like Christopher Columbus’ 1492 voyage. Economic historians propose an intermediate date and insist on the quantitative leap in long-distance exchanges of the 19th Century [ROU 04]. Flynn and Giráldez [FLY 04] propose the aforementioned start date of the Manila-Acapulco maritime connection in 1571 as being the first year of globalization.

The lack of consensus on the single date weakens the vision of a “big bang” and “one shot” of globalization. The levels of worldwide integration have always been weak, with entire continents being forgotten for a very long time. The presence of anatomically modern humans has been attested to for 24 kyr in modern-day Canada. Renaissance navigators began to close a long period of oblivion in this part of the globe. However, they belonged to maritime civilizations that were only regional, as definitely attested to in the logbook from the Manila Galleon. It would likely be better to speak of successive episodes of globalization and of fragmentation, as suggested by the study of cultural and linguistic diversity. This was very limited at the time of the demographic “bottleneck”, reaching its zenith at the end of the Paleolithic before the arrival of the productive economy. The industrial globalization of the 19th Century is ambiguous, with a reappearance of the fragmentation that clearly grew in the period of the two world wars [BÉN 08].

Daniel Cohen [COH 12] preferred to speak of three globalizations, that of maritime civilizations, which lasted until 1800, that of industrial globalization in the 19th Century and contemporary globalization. The Manila Galleon marked the start of a regular maritime connection, ensured by a giant of the seas for the era of maritime civilizations. The respective size of these giants of the sea grew throughout the three globalizations (see Figure I.4).

Figure I.4. A Manila Galleon (2,000 tons), the Titanic (46,300 tons) and Allure of the Seas (220,000 UMS)

Let us summarize the arguments in favor of Flynn and Giráldez [FLY 04], which connect the period of the first circumnavigations with globalization, and those that remain doubtful faced with this historic “continuity” of the Manila Galleon until today [ROU 04].

Flynn and Giráldez’s definition of globalization is based on the existence of a permanent link between all the densely populated parts of the globe, with significant exchanges in terms of both volume and value. When English sea captain Francis Drake returned part of the plunder from a Manila Galleon that he had captured in London, this contribution alone exceeded the British crown’s entire earnings from the year 1580. The city of Manila was founded in 1571, with naval construction activity. Spanish law limited galleon size to 300 tons, then starting in 1593, a maximum of two galleons together for transpacific trade. Even before the 1593 regulation, ships weighing more than 700 tons were being built in Manila [PAL 12]. The arrival of an inspector sent by the Spanish crown brought about a general strike in 1636 in Manila itself. Submarine archaeology estimates that a galleon that sank in the Marianna Islands in 1638 weighed 2,000 tons.

The San José that sank in Manila in 1694 weighed 1,600 tons. The transpacific maritime connection was performed at first by small flotillas, generally made up of three or four units for the Manila-Acupulco connection, as for Vasco de Gama and Francis Drake’s voyages. Safety was improved in the 17th Century with the annual round trip of one giant of the seas. “Once trade was established, it was impossible to stop” [PAL 12]. However, the mercantilist theories expressed in the mid-16th Century led to the start of precious metal exports and product imports. The pamphlets denouncing the transpacific connection in the Iberian Peninsula flourished, and the vehemence of their injunctions created a polemic space between the mercantilism of these counselors in the metropolis and a reality of long-distance commercial exchanges.

Rourke and Williamson’s counterargument [ROU 04] rests on a definition of globalization centered on the beginning of economic integration, with price convergencies taking place around 1820, just as the Spanish transpacific connection was coming to an end due to the Mexican War of Independence and privateering, i.e. the piracy practiced to benefit public coffers. The world experienced extreme fragmentation during the Manila Galleon era and protection was important, as for Japan, which only accepted one ship per year into its ports until 1854. The Manila Galleon had a penitentiary function, transporting anyone suspected of not being a good Roman Catholic either to the Inquisition Tribunal or to the Pacific galleys. The growth of global commerce was around 1% during the Manila galleon period, increasing to approximately 3.8% starting in the mid-19th Century. The description of the Bay of Acapulco in the Manila Galleon period was that of a large temporary fair upon the arrival of a ship, the few thousand people running this fair leaving the area once the stalls were packed up again. Quite often, along the Manila-Acapulco route, the northern route taken by the galleon, when it seemed that the Spanish were unaware of the Hawaiian Islands, was so long that only one ghost ship with its equipment and passengers who had died of illness and hunger arrived after 7 months of sailing around America. The frequency of this maritime connection was low, 110 trips in the end; in other words, an average of one trip every 2 years and 3 months.

While the feudal lords of Nagasaki only tolerated one ship per year, the Spanish crown authorized two transpacific galleons, but these had a biennial rate. This weakens Flynn and Giráldez’s statement: certainly, there is a significant volume of exchanges between the different parts of the world, but the societies at the end of these commercial routes remain politically closed and strongly hierarchized. And whether this be for the Silk Road or rivalries between the maritime powers, long-distance commerce led to the flourishing of much more important cities than the modest market town of Acapulco and its biennial fair in the 17th Century. Using Flynn and Giráldez’s definition of globalization, that of exchanges between the different parts of the world, the date of origin inexorably goes back to the episodes of growth in exchanges from the installation of silk routes and Mediterranean maritime routes. Since the beginning of the metal ages, “the Mediterraean has started to truly become that of contacts, of enlarging spaces, of transmitting ideas and techniques” [GUI 05]. Bronzemakers likely arrived in China via the open land route created by the shrinking of the Siberian forest, even though the existence of rivalries between maritime civilizations or those connected by commercial routes with a rather stable level of technology characterized a very long period and made initiatives like Flynn and Giráldez’s to fix a single start date for globalization difficult.

Even for aboriginal groups that were greatly isolated for tens of thousands of years, an initial contact date can be found in the successful contributions of phases of globalization and fragmentation. In the great Siberian north, the Cossack cavalry responsible for collecting taxes for the tsar established the very first contact with the elk hunters in Kolyma in 1639. The tax collector noted that the Yukagir wore silver jewelry, but they had never seen horses. The recent permafrost thaw made it possible to dig out Yukagir artisanal bone and mammoth tusk worksites. These sites date back to the era of the first expansion of anatomically modern humans, which means that they were contemporary with Aurignacian sites from Western Europe. For example, an ivory hairband represents an animal with ringed eyes and a large smile, most likely a protective dragon in the image of a boreal whale. The handicraft from the mammoth worksites of the first

Yukagir did not represent the sun, but rather ethnographic data [PIT 12]. The “solarization” of religious beliefs was thus a local cultural dynamic, understandable for groups that saw the long arctic night each year. The influence of the great Siberian north in the spread of a solar culture is seen in the mythologies of Amerinidian and Eurasian groups. In Greek mythology, Apollo first resides in the great north before coming to Delphi. It is therefore impossible to give a single date of initial contact, even for very isolated groups. These are forms of exchange and solidarity that transform throughout different large phases. An initial episode was the adaptation of myths of animals from another climate to the arctic fauna: for example, the boreal whale is a dragon, whereas those are rather based on snakes, animals exclusively found in warm climates. The development of a sun cult by these groups in Beringia has large-scale repercussions. Silvermithery indicates that these arctic groups had contact with others that had mastered metal work. Even 500 km into the Arctic Circle, every phase of globalization had been experienced.

Thus, these arguments come together to reinforce those already advanced by Rourke and Williamson [ROU 04]. What is shared will have different characteristics in the different episodes of globalization, separated by cesuras like the one defended by Rourke and Williamson around 1800 between the long previous period of rivalries of the maritime powers and the true start of the first industrialization in the 19th Century.

What is shared is first of all an ancient, paleolithic cultural foundation. This is a set of myths and rites that can be classified as a so-called “animist” and “shamanic” religion. This foundation was largely spread by regional contributions throughout the spread of anatomically modern humans across the land. In this textbook case, globalization has a multiplying effect for cultural specifications and increases their variety.

During the period of rivalries between maritime powers, there were acculturations and acclimations. The potato from America arrived in Shanghai in 1606, whereas the Mexican textiles from the 17th Century reproduced Asian motifs. These are barter economies, or segmented monetary economies, i.e. the price differences between two trading posts bring about the importance of profit for the merchant, whereas the difficulties of transportation and the regulatory limitations explain the situation of a limited flow of exchanges. Conceptually and in practice, commerce and pillaging are closely tied and often brought together in slave trafficking.

The characteristics of industrial globalization in the 19th Century affected financial investments, information, migration and exchanges of merchandise. The formation of a global market was seen in price convergences, e.g. those for wheat, cotton and steel [BÉN 08, p. 29]. Starting in 1870, the telegraph enabled instantaneous circulation of information around the world.

To characterize contemporary globalization, a simple sharing of information on a global scale, the existence of worldwide reference prices and large volumes of commercial and financial transactions do not provide a definition that covers the specificities that appeared in this new phase – they are characteristics of previous phases of globalization. Work markets remain greatly segmented, even though contemporary globalization cannot be defined as a deepening of global economic integration, despite being quite significant since the 19th Century. The behaviors of companies and households are partly determined by distant events and globally shared information: this global insertion of agents provides a better definition of contemporary globalization.

These phases of globalization can be broken up into phases of fragmentation. Descola noted a tendency for the local inscription of hunter–gatherer cultures, myths helping to explain singularities in the local topography, whereas they initially reported a rivalry between two animal spirits with no reference to a particular location, for example. The periods of political fragmentation and bellicose rivalry also contribute to these divisions.

I.3.1. Episodes of globalization and birth of the arts

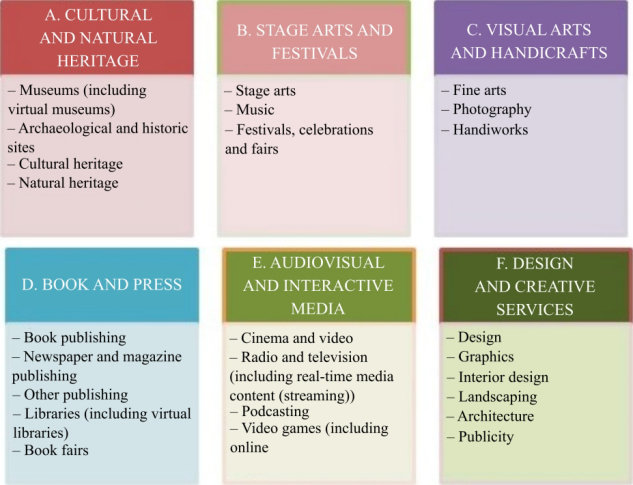

UNESCO’s 2009 nomenclature for cultural and creative activities includes a subdivision into six groups of art. The birth of these groups of art can be split up according to four primary episodes of globalization. In antiquity, the muses’ procession was led by Apollo and his zither, thus Music. UNESCO’s statistics indicate that the most significant sector today in terms of relative weight is that of the recently introduced animated arts (code E in the nomenclature), primarily television.

Code A in UNESCO’s nomenclature is that of valorizing cultural, natural, historic and landscape heritage. These activities developed in the 19th Century, with the development of the first tourism.

Figure I.5. Nomenclature of cultural and creative activities

Code B in UNESCO’s nomenclature is that of “stage arts and festivals”, including music. Although live performances developed particularly in the Meditarranean realm in the first millennium BCE, musical instruments and dance performances have been around since the arrival of anatomically modern humans in all parts of the globe.

Code C in UNESCO’s nomenclature includes handiworks, the fine arts and photography. Only the artistic legitimacy of photography is recent, acquired after having fueled reflections on industrial processes in cultural and creative activities.

Code D brings together publishing and the press. Processes of reproduction using xylography appeared at the end of the first millennium on the Silk Road, with the expansion of the Buddhist religion.

Code E includes all of the new media since the introduction of cinema at the end of the 19th Century. It was on the topic of television that Marshall McLuhan introduced the expression of a “global village”, and it is thus this group of arts that is associated with contemporary globalization.

Code F of UNESCO’s nomenclature is that of “design and creative services”, particularly architecture. This final group is closely tied to the beginning of the productive economy, i.e. the transition toward agriculture.

Figure I.6. The birth of the arts and the phases of globalization

I.3.2. Ecstasy, sacrifice, communication

While the most recent arts saw a secular birth, the oldest, up to the first books on the Silk Road, were born out of a religious context. Live performances in ancient Rome were still not fully secularized; the ancient Romans went to the circus for a sacrificial ceremony.

Bataille starts with one single hypothesis: sacrifice opens both the artistic and sacred space. He perceived that this hypothesis could not be supported after the discovery of the Lascaux cave, which did not contain a single tangible element harking back to a sacrificial practice. Moreover, Bataille concludes that prehistorians’ conception of the era of “magic of the hunt” is much too narrow. Prehistorians today remain divided on the shamanic hypothesis, that of a religion of ecstasy, which is defended by specialists in the transition from the Upper Paleolithic.

In his homage to Georges Bataille, Michel Foucault defines secular societies not as a “limited and positive world”, but as one “that comes undone through the experience of limitation, is made and unmade in the excess that transgresses it” [FOU 01, p. 264]. Foucault cites four major forms of this “experience of limitation”. The first is laughter, which seems to be common to all human societies. The other forms are ecstasy, sacrifice and communication. This series allows Bataille’s initial hypothesis on the birth of the arts to be rearranged. Sacrifice is a live performance. In a shamanic healing ritual, there can be dances, music, but no statute concerning the spectator. In sacrifice, it is necessary for there to be a community watching, or simply represented. Bataille’s hypothesis on a link between the birth of art and sacrifice should not be fully rejected. It does, however, target a limited set of specific arts, a development of the live performance associated with societies that are closer to ours than societies from the transition to the Upper Paleolithic.

An Etruscan tomb displays a fresco detailing the games organized in favor of the Dioscuri. These gatherings were famous all across the Mediterranean region for their boxing gala. Other athletic tests, as well as musicians and other artists, brought life to these games. The aedile’s staff granted for the organizer most likely honored the important figure to whom this tomb was dedicated. This fresco associates offering and sacrifice with the elaboration of a live performance requiring a mixture of artistic and athletic know-how that still seems novel to us today. Likewise, Bataille cites the case of the Aztec civilization, with the spectacular dimension of its sacrificial practices, which greatly illustrates his initial hypothesis. However, for Lascaux and the other first manifestations of artistic practices, the wonder and joy were taught, and it was indeed ecstasy that represented the experience of limitation for this society. Bataille mentions communication as “an immense hallelujah lost in the endless silence”, and this regime of transgression was already that of xylographic reproductions from the Silk Road starting in the ninth Century CE.

The transition to a sacrificial religion arouses discussion from archaeological material. The Younger Dryas (12.7 kyr/11.5 kyr) marks the final end of the last ice age. It was the last large cold oscillation lasting 1,300 years. It seems that the cultures present in this oscillation were sacrificial. The Clovis culture was a cultural unification present in the territories that correspond to Mexico and the United States today. It is known through important deposits of large points, so-called Clovis points. Sometimes, these deposits include the bones of newborns. Genetic studies and knowledge of the sacrificial rites and associated myths make the link between the Clovis culture and the Pre-Colombian civilizations of Mesoamerica. The ritual could be intensified due to the climatic crisis, interrupted by the consequences of the temperature drop, then started again, and finally abandoned in the configuration that is left in these kinds of deposits. These clues lead to the thought that there was a local presence of great sacrificial practices just slightly prior to the end of the ice age, modifying Bataille’s affirmation that the Paleolithic period did not see sacrifices.

In Roman Antiquity, there was ritual associated with procession, sacrifice and performance. The sacrifice was indeed part of a birth of certain arts, expanding the forms of live performance. Thus, on a site from Belgian Gaul like Ribemont-sur-Ancre, the Gaul tribe’s triumphs came one after the other, a torment of the vanquished whose bones were gathered in an aedicule included in a sacred area. Even in late antiquity, torment of the vanquished was organized by imperial power. However, the Romanization on the site of Ribemont-sur-Ancre brought about the construction of a theater with a small stage, most likely only adapted to pantomime. Romanization is a centralization of the sacrificial power. It introduced an urban hierarchy according to the types of live performances: in provincial towns, pantomime; in imperial cities, circus games, chariot races and military triumphs.

Three strata can thus be distinguished in the prolongation of Bataille’s questioning of the transgression and experiences of limitation. The oldest is that of Ecstasy, then comes Sacrifice and finally that of Communication.

I.4. Creativity and innovation

An innovation system is defined by the set of deciding factors that are involved in the formation, conservation, spread and use of innovations. It is generally made up of a regulatory and institutional framework, as well as public authorities implementing local, sectoral or national policies, with a demand that is more or less open to novelty, and a set of companies and organizations involved in all or part of an innovation process.

A general influence on innovation is creativity. Since the first human societies, it has been present. However, the conservation of know-how is a problem, it seems, as witnessed by the first island populations that may have lost nautical know-how, which they nevertheless had perfect mastery over upon their arrival by sea. The innovation system therefore plays a determinative role for the social utility resulting from creativity. For example, this can favor martial uses and thus trap creativity in games where everyone loses in practice.

The only galleon that remains today is the Swedish Wasa, the size of the sea giants of the period, weighing in at 1,400 tons and equipped with 64 cannons. It sank in 1628 during its inaugural voyage; it was recovered in the 20th Century. The nautical qualities of the ship are very mediocre due to the focus on the increase in firepower and general design problems. The very long period of rivalry between maritime powers only saw slowed progression in the technological domain. This example of the Wasa helps us understand why. An innovation system attempts to transform from a model of large commercial ships into one of combat units. This failed attempt indicates multiple dysfunctions, both in the preparation of the project and in the execution thereof. Spanish regulation means that the knowhow of the naval construction site in Manila should not even exist and that the king of Sweden could only attempt to imitate these great achievements through estimation based on hearsay from far overseas. The launch of the Wasa took place with too little ballast, while the portholes on the lower cannon stage remained open to launch sandblasted volleys. The ship sank after the very first breeze.

March [MAR 91] introduced an analysis of innovation systems according to an articulation between exploration and exploitation. Good exploitation is that of practical communities that create goods and products. In the example of the Wasa, the dysfunctions in exploitation during its launch led to the loss of the ship. Exploration is the previous job of preparation, the job of research centers and engineering offices. The galleon’s weak nautical properties resulted from dysfunctions in this exploration phase. During the period of maritime rivalries, innovation systems were greatly affected by the conditions produced through exploration and exploitation.

I.5. Summary of the work

Chapter 1 reviews the place of innovations in globalization theories and attempts to characterize some salient facts from the period ranging from 1985 to today.

Three methods exist to state the themes of globalization and innovation: expansion strategies through local innovation, “born global” innovations and, lastly, pairing between organizations in the framework of globalization and global collaborations [ARC 99]. This explanation is found in five chapters: in addition to Chapter 1 focusing on the transformations of theoretical references and Chapters 2–4 focusing on the different aspects of innovation and globalization, Chapter 5 discusses the transformations of collective action in innovation systems.

Table I.1. Globalization and innovation: outline of the work

(source: [ARC 99, p. 244])

| Actors | Forms | Stock | Tendency | |

| Expansion of local innovation (Chapter 2) | Companies, businessmen | Export of innovative goods Sale of licenses and patents Production in the world of innovative goods | Very high | Constant increase over a long period |

| Global generation of innovation (Chapter 3) | Companies, NGOs (nongovernmental organizations) | Acquisition of innovations, global management of innovations Research and development in host nations | Moderate | Increasing |

| Global collaboration for innovation (Chapter 4) | Universities and research organizations | Joint scientific projects Collaborations | Significant | Increasing |

| Companies, venture capital companies | Joint ventures Technology transfer agreements | Low | Increasing |