Choice, chance and (less than) certainty

This chapter

Before we look at some case studies and consider the impact of change on an organisation, this chapter will conclude the process of establishing the Preferred Scenario, but start the process by which the skills we have learnt are translated into our own future behaviours. In this, these final words set out to create a mindset for how we view our future after we have completed the Preferred Scenario. There will be a discussion about what to look for in our environment and we will conclude with a review of the major issues which seem to be looming on the horizon. Through all of our days ahead we will be dealing with the three Cs. We will have less than Certainty, we will experience Chance and random events which will affect us greatly, but through it all we will have Choice.

Chance and randomness

A wonderfully entertaining and thoughtful book by Leonard Mlodinow entitled The Drunkard’s Walk: How randomness rules our lives should be one of our personal guides to the future. ‘The greatest challenge in understanding the role of randomness in life is that although the basic principles of randomness arise from everyday logic, many of the consequences that follow from those principles prove counterintuitive.’1Mlodinow offers a number of examples to illustrate the power of random events. One concerns the baseball careers of Babe Ruth and Roger Maris. One could equally translate this example into the sports of cricket, ice hockey or whatever. Babe Ruth in his career had established a season high number of home runs at 60 in a season. Nobody had broken that record. Then in a remarkable season Roger Maris and Mickey Mantle slugged it out to beat the Babe Ruth record. Maris succeeded in hitting 61 home runs in a season. Maris’s career both before and afterwards never came close to the magical figure of 60 home runs. He had never hit more than 39 home runs in a season. He was clearly a good player but his performance excelled in that one season which he was never able to replicate. It all came together for him. Mlodinow demonstrates through the use of statistics that his extraordinary performance can be explained as much by chance as by other orderly explanations about talent and training.2 As Mlodinow says, ‘When we look at extraordinary accomplishments in sports – or elsewhere – we should keep in mind that extraordinary events can happen without extraordinary causes. Random events often look like nonrandom events, and in interpreting human affairs we must take care not to confuse the two. Though it has taken centuries, scientists have learned to look beyond apparent order and recognize the hidden randomness in both nature and everyday life.’3

Arguments have ensued for years about why Maris was able to succeed in one season but never again. These explanations include fear of failure, injury and also being unable to cope with success. The record performance, however, can as readily be explained by random events. So this evidences how our view of the past and of the future can be shaped by false understandings rather than by a simpler explanation as a random event. ‘If the details we are given fit our mental picture of something, then the more details in a scenario, the more real it seems and hence the more probable we consider it to be – even though any act of adding less-than-certain details to a conjecture makes the conjecture less probable.’4 There is a clear inconsistency between probability theory and our own interpretation of our futures – an area of uncertainty. This does not mean that we cannot work at predicting the future but it does add notes of caution as we move on from our Preferred Scenario.

Mlodinow explains that ‘The probability that two events will both occur can never be greater than the probability that each will occur individually.’5 He provides various examples drawn from the literature of psychology and statistics to illustrate this. They are worth reading if you are interested in these laws of probability. From our perspective, it is the case that we try to interpret the future by what we consider to be the more likely and yet the cues which we take from our world are often skewed by our experiences and interpretation of what is probable. The necessary skill to develop is to recognise that we do skew our predictions and to understand the effect which this will have on what we decide. It is also important not to close one’s mind to what could be possible.

Mlodinow relates the famous case of the columnist Marilyn vos Savant, renowned for being the person with the highest recorded IQ of 228.6 She was commenting on the issue of probability in the television game Let’s Make a Deal. The contestant winning the show was asked to choose their prize by selecting the prize behind one of three doors. This is also called The Monty Hall Problem. Behind two of the doors was nothing, while the real prize was behind the third door. If the contestant chose one door and then the host of the programme opened one of the remaining doors to reveal that it contained no prize, should the contestant change the choice which was already made? Marilyn vos Savant said that the contestant should change the choice to the other remaining choice. Mathematicians across the country all came out to say that she had got her advice wrong. Nobody stood by Marilyn. In fact, she was correct and yet it took a long time for this to be accepted publicly.7 The seemingly obvious solution that there was now a 50/50 chance of success, having had one of the choices negated, was wrong. Yet all the experts howled and berated this columnist. The point of this story here is not in the solution but that so many people fell into line with each other to deride vos Savant: a group-thinking position.

The most obvious answer is not necessarily the correct one. So it is important not to be blinded by the tyranny of the expert or, more especially, the tyranny of many voices. The issue of what is most probable or least probable can be seen as a statistical exercise but also should be recognised as a problem when predicting the future. The Monty Hall Problem illustrates the careful application of logic in the world of probability. To choose correctly in this game is to win on average 66 per cent more often than those who saw the probability as being 50 per cent. To increase one’s chances of success in any enterprise is always highly desirable. To recognise the application of probability and the role of chance will be crucial in maintaining the future tracking of the Library or Information Service.

The game of chess is an excellent training ground for predicting the future or at least working toward it. The mental training of working to plan a move and to understand the range of options open to your opponent is very worthwhile. The mental exercise to then try and predict the range of your future moves with the corresponding range of options open to your opponent becomes more and more complex. It is less easy to see the future in this forward-looking exercise than it is to see the past reasons or mistakes in the game of chess. Nonetheless, the application and mental rigour of a chess game is an excellent discipline to good thinking, planning and application of probability.

Adoption of risk

To be successful we have to be open to failure. To be able to predict the future we have to have experienced failure. We have different tolerances for risk which can be individually based or even cultural. We all engage in risk every day in many more ways than we are conscious of. But it is the role of risk and the society’s attitude toward risk which is of interest here. Sociologists would argue that risk is being treated differently now socially than, say, thirty years ago. Ulrich Beck indeed believes that our society had become a risk society and this view has influenced much of the thinking relating to risk and uncertainty.8 Most often we identify risk in order to avoid it altogether but we can always choose a level of risk. The notion of risk is important in terms of our aspiration to control it and to therefore better predict the future.

If you want to succeed, double your failure rate. (IBM Pioneer Thomas J. Watson9)

If we had only certainty in our world there would be no risk, but we have uncertainty into the future and therefore there are various levels of risk. If we cannot eliminate risk we have to deal with it in our lives and organisations. Risk management is practised in order to reduce the probability of known risk and difficulties. But where events and technologies are changing so rapidly, it is difficult as we are dealing with higher levels of uncertainty. Jakob Arnoldi emphasises that ‘risks are not actual but rather potential dangers’.10 The risks we are dealing with are disruptive across a range of industries allied to libraries. Thinking about the issues in this chapter in these terms might link for us the concepts of risk and uncertainty. We can decide the levels of both that we can tolerate; and what is probable and that which is not.

This chapter thus far has looked at the role of probability and chance as we might experience it in the future. So it is useful in what remains of this section of the book to look at some of the issues which will most likely have some significant impact on our futures in our endeavours. There are a few issues which will need to be heeded in the near future.

Issue 1: abundance of data

The abundance of data is overwhelming the world. The amount of data being collected in the world is astronomical. ‘Wal-Mart, a retail giant, handles more than 1 million customer transactions every hour, feeding databases estimated at more than 2.5 petabytes – the equivalent of 167 times the books in America’s Library of Congress. … The world contains an unimaginably vast amount of digital information which is getting vaster ever more rapidly.’11 The volume of data is causing huge environmental difficulties with the amount of water being consumed just to keep the computer centres able to keep their vast banks of servers in air-conditioned comfort. The amount of heat being generated by computers is rising beyond all expectation, especially in a world suffering increasing scarcity of water.

The data, at the same time, offers confusion with how to comprehend what it means and also significant opportunities to understand what users are doing with the data. The data is creating new business models for those who can use the data to comprehend what it is reflecting. Google is one obvious example, where they have been able to harness the data using their PageRank algorithm counting the number of links from other website pages coming to this particular website. This was a significant departure from the previous counts of words on individual web pages to ascertain the ‘relevance’ of particular searches. Google keep much of what they learn from our searches across their search engine secret, in that it has real economic value to the advertisers who contribute much of their tens of billions of income annually. Over 99 per cent of their income is derived from advertising, although Google handles only half of the world’s Internet searches. Clearly, company logistical operations have benefited enormously from the powerful use of computers to predict the location for and need of particular product lines from their customers. It is reported that for just one ingredient, vanilla, Nestlé was able to reduce the number of specifications and use fewer suppliers, resulting in a saving of $30 million each year.12 So it is the case with many logistics operations globally.

The business of using words as data is very small indeed. Researchers at the University of California (San Diego) examined the flow of data to American households. They found that in 2008 such households were bombarded with 3.6 zetabytes13 of information (or 34 gigabytes per person per day). An alarming example is the calculation of ‘A Day in the Life of an E-mail’. What starts out as a 1.1 MB message sent to four people will convert to 51.5 MB at the end of the day as it is stored, transmitted and backed up. The more responses to the message and the longer the conversation trails the worse the situation becomes.14

Figure 8.1 How 3.6 zettabytes of data get consumed Source: http://gizmodo.com/5423599/how-36-zettabytes-of-data-get-consumed (accessed 6 April 2010)

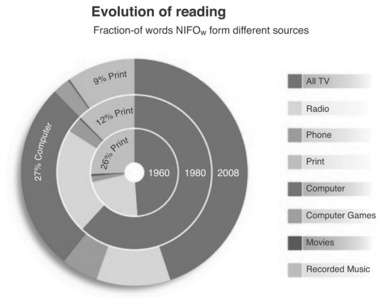

The biggest data hogs were video games and television. In terms of bytes, written words are insignificant, amounting to less than 0.1 per cent of the total. 15 However, the amount of reading people do, previously in decline because of television, has almost tripled since 1980, thanks to all that text on the Internet.16 This is a limited study, not taking into account the business use of words as data. So data is important but words are not in the total context.

But even while the amount of word bytes is relatively small, we know so little about our user behaviours and interests. Among librarians there has been an emphasis on the use of the Integrated Library Systems (ILS) with very little understanding of what is happening and virtually no understanding of what is happening with e-serials and now e-books. This is despite the fact that many libraries are now committing around 75 per cent of their acquisitions budgets to digital resources. Libraries need to investigate and understand what information behaviours are being exhibited. They need the equivalent of the Google business model invention of moving from word counts per page to counts of inbound websites. They need to move away from the very limited MARC descriptors of books to the types of searches which the users are using on the Internet. They need to partner with publishers in understanding the metrics of library content usage.

Issue 2: search engine capability

The immaturity of library search engines and the data structures which they search is of immense concern to all librarians. Research has clearly indicated that the first place for users to search is not the library’s O PAC, or computer catalogue. The library as a place of first resort is slipping.

This is partly due to the phenomenon of Google/Yahoo and their powerful search algorithms; sophisticated search engines giving the user ‘what they want’ or at least ‘what they accept’. They do this even by recording mistakes and giving access to the correct term or spelling but also by anticipating need. This ‘push’ capability is evident in systems such as Amazon, which provides related materials to the search while building histories of interested searches and possible materials of interest. These search systems obviously have huge computing capacity behind them but they have a fundamentally different approach or philosophy toward searching. In a time when all materials were in print, the catalogue served the purpose of allowing users to both search for groups of materials under subject headings but also pointing the user to a class or location number where further searching could occur on the shelves where books of a similar nature were clustered. Libraries have not fundamentally changed this search model but rather have incrementally built on this model. It is becoming increasingly unwieldy and creaking under the pressures of a digital environment.

The ILS (Integrated Library System) search engine is limited to searching the library’s collections of books while the metadata is limited to the MARC record search fields and a structured vocabulary. The terms which many of our users use are much more free-ranging and not limited to a structured language of subject headings. The newer search tools allow for user tagging, where additional search terms can be added to the item record. This is obviously good but it is an ‘after-the-event’ effort. The native searching of a wider set of terms is important to achieve the benefits of a structured language approach to the description of print and digital objects but also the natural searching behaviours of our library users.

Federated searching across different platforms or silos of information is a certain improvement but is still very clunky as this mode of searching struggles to deal with different proprietary systems. Federated searching and the use of standards such as Z39.50 have improved the integration of print and subscribed or owned digital resources significantly but much remains to be done to create seamless searching. It is ironic that a search tool such as Google Scholar yields good results for the user in a particular institution but, mostly, the end user scarcely realises how they have come to gain access to these resources. The situation feels to me as if our search systems are in transition to better ways which will yield easier and fuller access for our users.

Issue 3: avoid group thinking

It is always very difficult to be the lone voice in a crowded room. It takes a clear head with a strong background of thinking and research to have a view which is worth defending, especially when it is different to the prevailing view. It takes courage and commitment. Most often it does not come to this. Most often it is the case that there may be two views, with most people accepting the prevailing view and not working hard enough to question the existing view or to understand the newer or different view. It is often easier just to accept the ‘status quo’. Perhaps this is not directly ‘group thinking’ but it is dangerous. At another level it is stagnating thinking.

The danger of group thinking is that conversations between colleagues are too much in synch with each other. No external ideas or challenges are allowed into this mode of thinking. Various examples of where this has become dangerous have been related earlier in this book. No other explanation for a phenomenon can be entertained. In this circumstance different ideas are not even accepted or tested for relevance. There are a number of ways by which this problem can be managed and avoided.

It is important to read outside one’s own literature for social and technological developments, ideas, approaches to problems, solutions and challenges. An interesting aspect of our library operations is now the employment of people from different discipline backgrounds to help the organisation grow. A community of professionals! But in employing programmers, database managers, marketers, trainers, learning consultants, graphic artists and so on, do we allow these people to be part of the professional library planning and operational cultures? Do we allow them to question and to provoke different thinking? Why does the library do something? Why does it approach an issue in a particular manner? Does the library understand that users or groups of users think differently to the prevailing understanding which the library culture sees is the case? Why not try a different software? Why not push information to particular client groups?

If group thinking is stagnating in cerebral terms, the employment of different professional groupings is ‘eye-opening’, if we allow it to be. Admit the ideas and perceptions which these different professional groupings offer. Openly accept and discuss their ideas and observations. Their incorporation into the library culture or view of the world will open new insights but will also include and commit them to the library and its Preferred Scenario.

One final aspect of group thinking is to challenge our professional staff as they grow longer into their careers, when they may not be thinking as freshly as they once did. The emerging generational change can be a source of frustration for both the older and younger generations but it can also be a way of creating a stimulating and exciting culture of ideas and ambitions for the Preferred Scenario. Tensions are wonderful if managed correctly. Tensions can be between different generations or between different discipline groups in the employ of the library. As said earlier in this book, the library we are managing and designing is for future generations. It is a matter of blending new ideas and approaches with the intuition and experience of the management.

Issue 4: learn to take risks

Is risk a bad thing? What is risk? Can we achieve much with risk or without risk?

Risk is a peculiar thing. We do not live without risk at some level. We live because we risk. We risk to live! Much of what is being said about risk is perhaps not acknowledged as risk. Risk is not concerned with the past. Risk is future-focused. The achievement of any future is concerned with the management of risk. If a reference were drawn to the title of the book discussed earlier, The Drunkard’s Walk, someone under the influence of alcohol is scarcely concerned with risk. Alcohol reduces awareness of risk, or any of its threats or benefits. Intoxicated people are the most risk-tolerant of all. As library managers we will individually relate to risk to varying degrees, as much measured by our individual personalities and attributes. But risk will present itself to us and our response to it will determine outcomes.

Risk is, for the most part, associated with disaster or catastrophe. It is also seen to reflect the worst-case scenario; the scenario which none of us wishes to see realised. When dealing with uncertainty, as described earlier in this chapter, the choice of different levels and shades of risk will surely try us. Yet whenever money is given and invested, whether in a ‘bottom-line’ company or a not-for-profit service, all the elements of business activity are involved.17 There are many consortia in existence across the globe now. One of the best experiences any budding manager can have is to move from an expenditure-based organisation such as a library to an income-based organisation such as a not-for-profit organisation. The experience really does instil a real sense of what risk is, especially in uncertain times. The birth and growth of Lyrasis18 is a very good example of using scenario planning and the management of uncertainty.

Issue 5: continue to build a trust metric for the library

Trust is a vital aspect of all communication. If the source of the information being communicated is not trusted, neither will the information be. Trust is vital for publishers and for libraries. Publishers establish trust in their brand name as being respectable and authoritative. What follows is that books which they publish bear that authority. If a publisher has to withdraw a title because of plagiarism or other falsehoods, then there is a severe loss of reputation and trust.

The advent of the Internet has made huge amounts of information available, but very little of it is authoritative. So is material found on the Internet trustworthy? Well, much of it is clearly relayed without a known process by which the material gains authority. If there is no peer review process or respected publisher with their editorial processes then it is dangerous to assume that the material can be trusted.

Libraries have always been trusted organisations. They have been branded trustworthy in their own right as well as for the materials which they have made available. By extension, librarians are a trusted profession. But the Internet is creating unease in the community with these relationships. The Internet content is being accepted by many as valid even when it is plainly not. Libraries need to understand what business they are in. Newspapers thought that they were in the business of allowing people to advertise rather than helping people to sell things. This is a paradox.

There are two responses to this issue. Firstly, there is an educative aspect – a clear role for the librarian is to instruct in the ways by which content can be evaluated for authenticity. Secondly, there is a new role emerging by which web content could be stamped with a Kitemark.19 Trust is, as Kieron O’Hara has pointed out, ‘a wider attitude toward people and institutions that can as suddenly appear as disappear’.20

The issue of trust is a risk factor in the future of a library. It can be lost or could be extended into new realms. As indicated above, the risk of doing nothing is more dangerous than that of adopting new approaches. The reputation of trust in the library organisation and profession is at risk if one does nothing.

Issue 6: so what is your future?

In the final analysis, choice is with us through all the analysis and the articulation of futures in a Preferred Scenario. That future will not remain constant but will change and mutate. This final issue is effectively about making choices after the Preferred Scenario has been proclaimed and is in the process of being implemented.

A recent report on the challenges for academic libraries in difficult economic times reports that:

After a decade of growth in budgets and services, librarians now expect a sustained period of cuts. Library budgets have risen over the past ten years – although not as much as overall university income and expenditure – as both the volume and range of library services have expanded. Librarians from across the higher education (HE) sector now expect budget cuts over the next three years.

The scale of the cuts means that libraries must rethink the kinds and levels of service they provide in support of their universities’ missions. The scope for further simple efficiency savings is small, and so librarians are having to think more strategically about:

![]() the balance of expenditure on information resources on the one hand, and staffing on the other. The balance varies significantly across the sector, and there is a close relationship between staffing and service levels;

the balance of expenditure on information resources on the one hand, and staffing on the other. The balance varies significantly across the sector, and there is a close relationship between staffing and service levels;

![]() whether and if so how to sustain existing kinds and levels of services while at the same time developing new services to meet new needs. Many libraries across the sector are considering cuts in services; but they need to ensure that staff focus more on user-facing functions, and to develop a more detailed understanding of the costs of their activities;

whether and if so how to sustain existing kinds and levels of services while at the same time developing new services to meet new needs. Many libraries across the sector are considering cuts in services; but they need to ensure that staff focus more on user-facing functions, and to develop a more detailed understanding of the costs of their activities;

![]() the squeeze on book budgets, and how to meet the student demand for core texts. E-books could help ease this problem, but publishers’ policies on pricing and accessibility are inhibiting take-up; and

the squeeze on book budgets, and how to meet the student demand for core texts. E-books could help ease this problem, but publishers’ policies on pricing and accessibility are inhibiting take-up; and

![]() the costs and sustainability of current levels of journal provision. Cancelling large numbers of titles or a whole big deal will give rise to considerable opposition. But librarians are looking at various options to reduce the costs of their current portfolios.21

the costs and sustainability of current levels of journal provision. Cancelling large numbers of titles or a whole big deal will give rise to considerable opposition. But librarians are looking at various options to reduce the costs of their current portfolios.21

What has been learnt through this whole process is the need to research, to maintain a weather eye within the field of our own profession but also elsewhere. Most importantly we have learnt to collaborate and to be empowered by being open and sharing data and future positions. Tapscott and Williams, in their book Wikinomics, called it ‘collaborative minds: the power to think differently’.22 Among their arguments is that we are seeing the end of intellectual property as ideas and data are shared for greater effect and outcome. Certainly libraries need open-source solutions to be able to share the digital information they subscribe to and create. The traditional partnerships of the past still infiltrate our thinking about library and vendor: the vendor will do and libraries will service. Ken Haycock also highlights that the ‘public good’ is being replaced by public value.23 So return on investment (ROI) arguments are very important but extremely difficult in library environments to successfully operate. Collaborative librarianship is what I might describe not as doing it ourselves but having a genuine partnership of addressing disruption and creating new arrangements. This is a leadership where libraries shape what is to be delivered and how it is delivered in new partnership arrangements. It is proactive redefining of collection development which is the most pressing issue of the early years of the twenty-first century.

Decisions will be improved through being open and collaborative, with new skills being required to achieve the best futures out of this mode of thinking. Much research is happening into the processes of decision-making. Much as this book has advocated leaving decisions until the end in the process of creating scenarios, so too Thaler and Sunstein say that ‘by insisting that choices remain unrestricted, we think that the risks of inept or even corrupt designs are reduced’.24 Do not rush to locked-in leadership positions; leadership is more about creating the opportunities and the belief that the future is strong even if a little unclear.

Improving decision-making strategies in our libraries is a good way to bring the earlier issues into a framework which Thaler and Sunstein call their choice architecture. This is but one tool available through the literature. Their argument that people make the best decisions by leaving the strategic open as long as feasible is good, allowing for what they call ‘nudges’ rather than hard commitments one way or another. Nudging has a certain leadership flair to it as people can be nudged from one position to another while allowing an understanding of what is happening in their environment.

Conclusion

It is not intended to be prescriptive in bringing this part of the book to a close. The lessons of this work lie in the power of our imagination, our awareness of the impact of disruptive influences on our business models and what we might do to prepare for new futures. That is the simple message.

Clinging to ‘the way we did it’ is an almost instant recipe for disaster. The best solution for your organisation is not mine to determine, although this book might help you in your deliberations. The future is a wonderful and seductive mix of enticement and threat; it is alluring and it is frightening; in the end, we should all embrace it, for if you do not it will most certainly pass you by. Come on the journey. It will be exhilarating!

1.Mlodinow, L. (2008). The Drunkard’s Walk: How randomness rules our lives. London: Penguin Books, p. 7.

2.The performances covered in this baseball example are difficult to replicate in more recent baseball seasons that are contaminated by steroid abuse affecting performance.

3.Mlodinow, op. cit., p. 20.

4.Ibid., p. 24.

5.Ibid., p. 23.

6.A more complete explanation of this example is available at http://www.en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marilyn_vos_Savant (accessed on 20 July 2010).

7.Available at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Monty_Hall_problem (accessed on 20 July 2010).

8.Beck, U. (1986/1992). Risk Society: Towards a new modernity. New Delhi: Sage. (Translated from the German Risikogesellschaft, published in 1986.)

9.Available at: http://www.famousquotes.com/show/1049131 (accessed on 20 July 2010).

10.Arnoldi, J. (2009). Risk: An Introduction. Cambridge: Polity Press, p. 8.

11.‘Data, data everywhere’ The Economist 394(8671) 27 February 2010, p. 3.

12.‘Special report on managing information’, The Economist 394(8671) 27 February 2010, p. 6.

13.A zettabyte is equal to 1 billion terabytes. According to IDC, as of 2006 the total amount of digital data in existence was 0.161 zettabytes; the same paper estimates that by 2010, the rate of digital data generated worldwide will be 0.988 zettabytes per year. Mark Liberman calculated the storage requirements for all human speech ever spoken at 42 zettabytes, if digitised as 16 kHz 16-bit audio. This was done in response to a popular expression that states ‘all words ever spoken by human beings’ could be stored in approximately 5 exabytes of data (see exabyte for details). Liberman did ‘freely confess that maybe the authors [of the exabyte estimate] were thinking about text.’ Available at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zettabyte (accessed on 20 July 2010).

14.Gantz, J. F. (2008). ‘The diverse and exploding digital universe: An update forecast of worldwide information growth through 2011.’ An IDC White Paper. March 2008.

15.Available at: http://gizmodo.com/5423599/how-36-zettabytes-of-data-get-consumed (accessed on 20 July 2010).

16.The Economist, op. cit., p. 5.

17.Haycock, K. (2008). ‘Issues and trends’ in Ken Haycock and Brooke E. Sheldon (eds), The Portable MLIS: Insights from the experts. Westport, CT: Libraries Unlimited, p. 204

18.Available at: www.lyrasis.org (accessed on 20 July 2010).

19.A Kitemark is a quality measure designed to assure consumers of safety and value. There are a number of systems already in existence mainly in manufacturing but imminent in education circles.

20.O’Hara, K. (2004). Trust: From Socrates to spin. Cambridge: Totem Books, pp. 282–3.

21.Challenges for academic libraries in difficult economic times: a guide for senior institutional managers and policy makers. Available at: www.rin.ac.uk/system/files/attachments/Challenges-for-libraries-FINAL-March10.pdf: 4.

22.Tapscott, D. and Williams, A. D. (2006). Wikinomics: How mass collaboration changes everything. London: Atlantic Books, p. 268.

23.Haycock, op. cit., p. 205.

24.Thaler, R. and Sunstein, C. (2009). Nudge: Improving decisions about health, wealth and happiness. London, Penguin, p. 12