Designing your process

This chapter

The purpose of this chapter is to enable the reader to consider the very practical processes by which the scenarios can be created. The earlier chapters have effectively ‘set the scene’ and will be drawn upon to illustrate the process being described in the following pages. The process is a suggested one and is not the only way to achieve the scenarios. The exercises illustrated in the earlier chapters are especially useful in achieving input to the steps in this process.

The illiterate of the twenty-first century will not be those who cannot read and write, but those who cannot learn, unlearn and relearn. (Alvin Toffler)1

Not every process is the same

The case studies in Chapter 9 provide examples of what various organisations have achieved in Scenario Planning.2 Each organisation is different; each is in a different country; each is in a different library sector; one is not even a library but a library consortium organisation. So diversity is highlighted in the case studies. In the same way, the processes by which the scenarios were reached and managed is different, shaped by circumstance, by political realities; by the communities which are served and by the history and position of the organisation itself.

Scenario construction beginnings

The process described in this book will lead to a Preferred Scenario for your organisation. The process should be modified where it is deemed necessary. But if an organisation decides to embark on this process, it should fully commit to the process and be bold. Within your organisation there will be issues. Some of these issues will include a fear of a ‘loss of control’ in the process. Some of your colleagues may wish to ‘tone the process down’, or to use a more controlled process of simple strategic planning. These issues are a measure of the risk which your organisation may wish to entertain in designing the process. It may be a measure of a fear of the unknown and a fear of losing control in a process which seeks very strong involvement of the organisation’s stakeholders as well as the uncertain nature of what they may contribute through this process. It is a genuine concern for the owners of the process. It is important to have clear and open discussions at the senior levels of your organisation as to the nature of the process, the likely outcomes, the possible roadblocks and the organisation’s taste for risk. Having said all of this, the level of risk in losing control of the process is not high. This book contends that it is a greater risk not to engage in an open and frank discussion on the future position for the library and information service – a far greater risk!

When your organisation considers a scenario planning process, it is inherently recognising that the methods used in the past have not drawn out all the issues relating to where the organisation ought to be or be heading. The scenario planning process will not predict the future. It will not allocate the organisation’s resources to this activity or project. It will not establish new courses overnight. It will, however, construct stories of what might be! It will enable the organisation, its stakeholders, and staff to be excited about what might be and to embrace that future which might be seen to be three or five years into the future. The scenario planning process will construct a word story of your organisation’s agreed preferred future which will draw all the players together in one ‘vision’ of what should be. The shape of a library’s future is not or should not be driven only by the library managers but by all the members of its community. The professional library staff of course drive the process and provide the professional input. In this way there is far less risk that the future will not be owned by all, and that it will not be relevant to the organisation’s users. The imagination should dominate the scenario process; do not be dragged back by an overwhelming sense of reality past and present.

The suggested process

This book can now summarise the process of scenario construction as having seven steps. Each of these steps draws on the earlier chapters of this book and the exercises contained in them.

1 Design of the actual process

As discussed above, this step requires a commitment to see the process through. It also describes who will be engaged in the process and the extent of stakeholder engagement in the process. There are two basic audiences that will need to be part of the process, each for different reasons. Firstly, each library organisation or information service will have a community of stakeholders. Secondly, there will be a vital and very interested community of staff who could be very affected by the decisions in this process.

If your community base is large, there will be an issue of how participants will be invited to partake in the process.3 Is it to engage various representative student bodies at the undergraduate and postgraduate levels? Is it to engage key senior academic leaders in the community? Should this be at the Dean level or Head of Department? Should the Vice-President or equivalent level or the Mayor be invited to participate? Is it to engage various community organisations? In a consortium organisation, is it to engage Board members and all or some of the library members? The best path always is to involve a representative group of senior stakeholders who will be able to lend their weight to the process and its outcomes. These people will become champions for the Preferred Scenario at the end of the process. They will speak to the process and for the outcomes in many more fora than the library staff will be privileged to attend.

It is also very important to recognise another demographic. The Agreed Preferred Scenario will be focused on serving the organisation’s primary clientele so they should also be strongly involved in the process. In the case of an academic library, a future planning horizon for a time three or five years into the future will inevitably be for a student cohort which is not yet enrolled at the university. It is crucial to remember that the organisation being prepared for is for a generation which is sharply younger than the planners of this process. The generation will also be younger than the student cohort who will actually participate in the process! This will apply for most library sectors. Age will shape perceptions and outlooks. So it will be important to have as wide a representation as possible of the age groupings in your stakeholders.

These are questions concerning the composition of stakeholders in the process. The actual numbers of members of your community who are engaged in the process will depend largely on your choice and decision.

2 Understanding the community and environment

Understanding the broader environment as well as the local impacts is imperative in commencing this process. Articulating these impacts in various documents for the consideration of the Scenario Construction Group will provide their foundation for understanding. The analysis of the forces at play in the library and in its wider environment will greatly help. Understanding, for instance, the rate of activity in the library in terms of acquisitions, print versus electronic, and use activity in the physical and virtual libraries, as well as trends, is very useful. Analysing the trends in publishing in print and electronic and in the subject areas of interest to your community will provide an understanding of the extent to which the community is served with quality and relevant content. Projecting models for the possible development of and access to the Internet would enable some projected understanding of what impact these developments could have on library models. Understanding the future and trend funding impacts on the parent organisation is also useful. The organisation may be growing, may be under pressure, may be under review or may not see the relevance of the library. These and other analyses help create a broad understanding of the past, existing and future environments. They can be presented as documents to those who will participate in the focus groups and the Scenario Construction Workshop to inform them. Much of this is discussed in the next chapter.

Conducting Focus Groups to ascertain the issues from the community will also form a significant input into the process. The issues arising from both processes can be juxtaposed using the axes methodology described in Chapter 4. A number of these axes exercises will enable the various forces at play in the environment of the future to be contrasted.

3 Getting your chosen community to work together

The moment of truth is now arriving as all the preparation has been done. All the briefing documents for the groups have been chosen. We are now moving into the final phases where these groups contribute to the actual construction of the scenarios. It is a narrowing of the range of people who are involved and a heightening of the sense of destiny with the created scenarios.

Focus groups

There will be two types of focus group. They will be User and Staff focus groups. They will be separately conducted and provide different but valuable input. The output will reflect the general self-interest of that group. This output from each focus group should be recorded for later use. Differences in the range and intensity of the issues from each group will reflect the interest and perspectives of that demographic group. Issues from student groups will reflect issues peculiar to the interests and understanding of that group. They will importantly reflect the ways in which that generation wish to study and the facilities which they would prefer to have in order to achieve that environment. If one of the exercises carried out with this group was to list their five top issues for the future library, then the results will be a rich field to examine. A general grouping of the results will reveal much. By this, I mean to roughly create categories into which the issues may fall. The categories may be Building, Learning, Technology, Finance and so on. The number of issues in each of these categories will diminish. A word count is a more sophisticated view of the interests of each group. This can be aggregated and cross-sliced to understand the different demographic interests.

The staff groups will often display different perspectives about the future than the students, for instance. There will be elements here of insecurity as the environment which they have known and been comfortable in is now being made subject to change.

Scenario construction workshop

This workshop is the vehicle by which the scenario will be constructed. It is therefore important to have its composition well thought through. This workshop will provide all the data and orientation for the possible futures of your organisation. You have already defined the groups who are your organisation’s stakeholders, in terms of use, funding, partnership (internal and external), staff and suppliers. It is important to invite a range of these stakeholders to participate in the workshop. It is important to be careful to achieve a balance of senior and more junior people to create a wide cross-section of interests for the workshop. It is also good to identify some members of the community who will naturally act as protagonists; who will add controversial or more ‘radical’ views; who will think ‘outside of the box’. An effective workshop will have between 30 and 40 attendees.

The facilitator for the workshop must have a fluent understanding of the ambition and desired outcome of the workshop. That person should be familiar with scenario planning techniques and the need to use imagination and to create stories about the organisation’s future without trying to bed the stories down in a strategic plan. The facilitator should allow the stories to develop almost organically and without rush or pushing in a particular direction or other. All the good ideas need to come out of the workshop participants as naturally and easily as is possible.

4 Suggested ways to operate the scenario construction workshop

The group who eventually form this workshop will never have worked together before. Many will not know each other at all, or perhaps only by reference. The environment of the workshop facility needs to be casual, with good food easily available. It is desirable to form the groups beforehand so that different interests and attitudes are contained as much as possible in each group. In a total workshop of 40 persons, five groups of eight persons might be formed. Each group should ideally have a senior library person to explain any issues which the group might have about the process or certain details which they might want clarified. The staff person can also reinforce that the group does have the power to suggest change and different outcomes! An ‘ice breaker’ exercise is useful to make people feel relaxed and help them get to know each other. A discussion about the environment is again useful to set the scene for these participants, as also would be a summary (with the full focus group data available when requested) of the focus groups and their views and desired directions. Drawing these issues into a group-wide discussion is useful to bring out the different and sometimes diverse perspectives. Every outlandish idea, every different perspective, every half-thought needs to be encouraged. All these ideas begin to create a stimulating atmosphere of possibilities and indeed probabilities. The groups will be encouraged to work together, teasing out this idea or that, this experience or that, this long-held view or that, and especially perspectives of what students and teachers or community leaders need from their future library. The final outcome will not be one idea or another but an amalgam of all of these perspectives.

5 Draw up the scenarios

At this stage there should be a further discussion about scenarios; examples of other institutional outcomes, such as those in the case studies in Chapter 9, will give the participants a flavour of what is being aimed for. It is not the objective of the workshop to finalise the polished words of each proposed scenario but to provide the skeleton and the major characteristics. It is a good exercise for each group to look at the issues which they or others have raised and start to lay down what they see as the most important or the most contentious. They can use the exercise of the axes to start imagining stories of what might be in the different quadrants.

The task of each group is to create three scenarios. The scenarios might represent three different levels of risk or a range of possibilities such as the present, an intermediate future, and a more radical future. The creation of three futures ensures that a range of options and choices remains in play as long as possible. It also avoids the debate, at this time, as to which future is best. Participants and the wider community will be attracted to each scenario but not all to the one scenario. The creation of three scenarios also enables these stories to be taken back to the community as evidence of possibilities which could be chosen for their organisation.

In creating a scenario a strong and evocative title for each scenario is good to identify their core elements. You can note some of the titles used in the case studies. The dynamics of the groups in the scenario construction process will always create something clear and defining about each scenario. What is the nature of the scenario being drawn up? Is it memorable? Does it capture the essence of the words being used to describe the scenario?

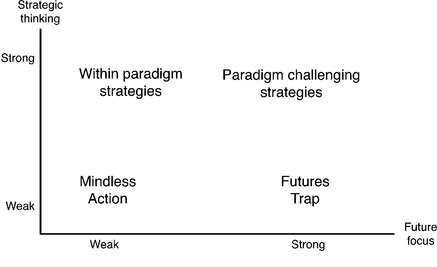

In creating a scenario it is important also to allow for change. The chart below looks at the range of possibilities which can exist. The options can be to stay within existing operating conditions or to change realities. This is often a useful scenario because it is a natural extension of the present and, in this way, is easy to create and imagine. It is within ‘the existing paradigm’ or mode of operating but it is a viable future. If the community wishes to accelerate change but without doing anything too radical then this may be the kind of outcome which is achieved or is described as a scenario.

The ‘Futures Trap’ is an imaginative option and allows for popular conceptions of where future technologies are taking us. It can stretch our own horizon and allow all those ideas which we may not have wanted to entertain or been able to afford. It may be the library which is very high tech providing unimaginable services or a scenario where the ‘library’ does not even exist. This scenario allows the futurist in each of us to come to the fore. We can allow our imaginations to run riot; we all have that imagination. This is often a release scenario. But it will have many serious and operational issues which will be kept in view with this scenario.

The ‘Mindless Action’ effectively is to do nothing. It may be to shuffle the old strategic plan and spruce it up a little but it is not going to fundamentally change the way in which the organisation is seen by its community and staff.

The workshop participants should be asked to create three scenarios, to describe each by providing a list of, say, ten bullet points outlining the various aspects to each scenario and to give each scenario an appropriate and lively title.

While working in a workshop with a number of groups, with each producing three scenarios, it is exciting to hear their presentations and to look at the degree of overlap between the creative efforts by the participants. The process of having the workshop merge different scenarios can mostly collapse twenty-four or so scenarios (assuming that there are eight groups and each group produces three scenarios) into three or maybe four scenarios. Once this is done, then the work of the workshop has been completed. The workshop objective is to achieve this collective view.

6 Writing up the scenario

This is a creative and stylistic effort by a writer engaged in this process or at least a close observer of it. The writer needs a sharp understanding of what is being said by the participants, as well as an understanding of issues and language in the library and information profession and also in the wider educational or community environment. The style of each writer will vary and cannot be prescribed. It is crucial, though, that the scenarios have a focus on what will be the situation in three to five years’ time, depending on the chosen time horizon. Each scenario should be written describing the environment which has been achieved for that scenario at the end of the time period. It is as if the reality of that future is being described in words enticing the community to engage in the outcomes of that scenario. The tenses of the language need to be written in the sense that ‘we are now in this future which we had planned’. Take the reader of the scenario forward in time and create that sense of being there in that future.

This future orientation of the writing can be helped with phrases such as: ‘The Library in 2011 continues to be …’. Other approaches might be to describe the environment which has been achieved in that future frame: ‘The University community has engaged rapidly and completely with the possibilities of digital communication, access and work. The students actually prefer to work completely from their laptops …’. Other issues which the scenarios envisaged might be described as: ‘The organisation’s innovative focus has also led to its recent strategic alliance with an innovative … multi-media web company. Partnerships and commercially strategic alliances represent major opportunities, and a major direction, for this organisation and its customers.’ So different phrases and the use of positive achievement-orientated language can sell the particular scenario as an environment which has been achieved, albeit in the imagination of the workshop participants. The scenarios can be written more simply in terms of the relevance of the library to their own community: ‘Community and academic coffers have been depleted by crisis responses to a general economic decline along with decreased tax revenue. Funding for libraries is less available.’ This is a very valid descriptive approach setting a scene. In this case the words were created before the economic crisis which began in late 2008. This highlights the relevance of this imaginative approach. Another line: ‘The library offers learning programmes that are in high demand by the local community and faculty alike.’ The style of the writing and the actual approach can be designed for the community and purpose of the scenario planning process. Reading the scenario should evoke the feeling that the reader is in the described environment.

It is ideal to share the resulting scenarios back to the participants to gain feedback and to achieve a validation that the written scenarios are what were intended. Any feedback is useful and helpful and can be included in one way or another.

A decision has to be made at this point as to how to move from three scenarios to achieving the ‘Preferred Scenario’. This will be handled differently by each organisation conducting this process. The choice will be affected by the political situation, the sense of urgency in the organisation for a new future and/or the size of the community and the difficulty in communicating with that wider community. One library may use the three scenarios and establish a poster campaign to gain further feedback from the community of users as to what they see as being important in each scenario and to what scenario they are attracted. Another library may take the three scenarios to discussions with senior academic and student groups across the campus to gain feedback. This is an excellent opportunity to have the library issues and futures widely discussed on campus, while portraying a vibrant and active library leadership. A consortium organisation may establish a ‘roadshow’, taking the futures to the ‘owners’ of the organisation and seeking their reactions in their own home environments. There are, of course, many other processes which could be designed to meet particular circumstances. It may be that the organisation decides to merge the three scenarios internally without further external debate. From any of these processes the feedback can assist a small group into the final phase: to construct the Preferred Scenario.

7 Create the Preferred Scenario

In writing this final Preferred Scenario it is good to remember that this document will stand as a benchmark against which the future performance of the library organisation will be measured. It must be written to set the reader in the target year by which the Scenario is to be achieved. This is not what the organisation is going to achieve but what it has achieved. This orientation is critical. The next chapter will discuss where to go and what to plan once the Preferred Scenario has been agreed to. However, once the final feedback has been achieved, the Preferred Scenario will not just be one of the futures but will, to some extent, include aspects of a number of them. It will predominantly be one of the scenarios but it will include features gained from the other two. So it is not a matter of just choosing one future but of stretching the organisation’s capacity for risk and innovation in their future. The graph on page 122 highlights the need to place the Preferred Scenario as being strong on Future Focus and also Strategic Thinking. With this positioning, a challenging and exciting scenario can be created.

1.Toffler, A. (2010) Available at: http://thinkexist.com/quotes/alvin_toffler (accessed on 20 July 2010).

2.There are other examples now being used. A recent example is the ‘Bookends Scenarios’ developed for the Public Library section of the State Library of NSW. Available at: http://www.sl.nsw.gov.au/services/public_libraries/publications/docs/bookendsscenarios.pdf (accessed on 20 January 2010).

3.The titles of the stakeholders will vary in each library sector.