Understanding choices

If you limit your choices only to what seems possible or reasonable, you disconnect yourself from what you truly want, all that is left is compromise. (Robert Fritz1)

This chapter

The chapters previous to this have dealt with the nature of scenarios, how to understand the nature of the future and the disruptive influences or forces which shape those futures. This chapter is designed to help us deal with choices arising out of those deliberations: the choices we will need to make. It will also help us understand the nature of choices and how to deal with seemingly contrasting and/or contradictory positions in those choices. This chapter will especially deal with three main techniques which start at the simple issue level, move through the complex then on to the uncertain event approach. These three approaches can be used together or on their own. The first is often referred to as the Axis of Uncertainty, while the second might be called Alternative Scenarios and the third is the Unexpected or Surprise Futures approach. Each of these approaches is a tool to enable us to deal with choices; choices which need to be made at some point or another.

What are choices?

We make choices every day. Life would be boring or inactive without the choices we have the opportunity to make. To make our own choices is far more important than to have them made for us. Often choices are a matter of degree. We can have a drink of wine. We can choose to drink a little or a lot. There are consequences to choices along that continuum of a little to a lot. To choose a lot of wine will have health consequences or impacts on others while we are intoxicated. Health can be described as a matter of choice. A choice can be to seek good health or not to worry about one’s health. This again is a continuum. There are degrees of substance with wine also. We could choose red or white or even sparkling. This may be a matter of taste or situation but the choice is ours to make. So there are many library examples of choice. One can choose a level of service to be provided. One can choose the speed at which materials are made available in print or even electronically. One can choose to work collaboratively with other colleagues or libraries. One can choose to have more face-to-face service or more automated delivery of service.

Perhaps the first step is to understand the range of issues which are existent within an organisation. In doing this the staff can begin to understand the range of perspectives across a collective staff on the issues which matter to them. In a sense this illustrates the level of complexity and the variety of views even in one organisation. It will also illustrate the range of important issues which are not even on the radar of many in a library or information service staff.

Choices are affected by open discussion and the availability of diverse views. The Internet is often seen as an open field of views and opinions. This may be so but rather than helping to open minds and expose us to an unbiased array of unexpected viewpoints and useful information, the Internet actually causes us to become more closed minded. Cass Sunstein contends that we are witnessing an overall decline in the influence of ‘General interest intermediaries,’ and an increase in highly specialised areas of information, such as highly partisan cable television channels, or websites that allow us to ‘personalise’ the news we receive. In such a culture, he argues, ‘we have the ability to see only what already interests us and to filter out any exposure to the different concerns and political opinions of fellow citizens, thus preventing a truly democratic conversation.’2

If an organisation is facing a period of crucial change, it is important to engage all staff in some or many parts of the planning process. This is recognising that there will be an end to this planning process and a resulting implementation phase. Alerting all members of the staff to the range of issues at the beginning of the process can only help to psychologically prepare them for the mere fact of change, whatever it turns out to be. The management of change anxiety is important from the very outset. The exercise detailed below will bring out a surprising array of issues from one staff cohort; a surprising array of issues from staff at the same employment level; a surprising array of issues which many do not even begin to recognise as being important or existent.

The prominent author G.K. Chesterton made the following observation: ‘I owe my success to having listened respectfully to the very best advice, and then going away and doing the exact opposite.’3 Chesterton was renowned for his sense of paradox and being able to highlight extremes. In this quotation, we can recognise that even the unorthodox view should be examined as a real, possible and viable choice. Exercises such as that listed above will highlight issues and concerns in the organisation’s staff but will also enable some discussion of those concerns.

Linking with the work of the earlier chapters, we can now look at the range of issues confronting a library organisation but with a different perspective. If we have conducted the exercises as suggested in Chapter 2 we would have begun to understand what we think will happen to our collections over the next five to ten years. We will have views from within our organisation of its reliance on content, on print and on digital and the web. We will have explored the perceived impact which these changes will have on our budget, staff levels and skill requirements. Each of these understandings will differ from staff member to staff member; from library to library; from organisation to organisation. The important thing is that we have begun to get the organisation to look forward and to understand that the environment will be different and that, most likely, the perceived changes would happen sooner rather than later; quicker than we might anticipate. So in this process we have begun to make choices.

In understanding disruptive technologies we have looked at our library environment and have seen that technologies can emerge which radically change the business of an organisation. The emergence of the personal computer (PC) is the classic recent example. The advent of ‘cloud computing’ may have a similar impact. However, for libraries the emergence of the digital delivery of content to the end user has ‘disrupted’ the business model for libraries. It has led to the most fundamental re-examination of the library and its relationships to users, to vendors and to consortia. The environment is clearly complex and saturated with choices. If this disruption has already occurred to the library business model, then it is very important to recall this throughout the planning process.

Disruptive technologies can occur again to the library and/or to many of the component parts of the whole industry, thus creating further impacts. For example, a narrowing of ownership of publishing houses or distributors will have an impact on the economics of the library. A population take-up of devices such as the Kindle or the iPad could have a strong impact on the nature of publishing and where publishers choose to make their content available. Publisher business models will struggle with change and the impact on their revenue streams.

Beginning to construct scenarios through choices

Axes of uncertainty

We will talk in this chapter now about simple and more complex ways of beginning to create scenarios but, as with most issues of complexity, it is best to start as simply as possible. As mentioned above, choices can often be seen to be on a continuum, from one extreme to another. Two examples are pursued below which begin to illustrate how scenarios can be constructed.

In everyday life, two choices we might confront are between degrees of financial resource and the extremes of weather. The two variables might be illustrated as per Figure 4.1.

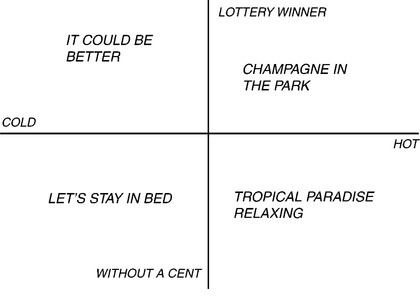

At first glance these two sets of choices do not sit easily with each other but if they are set at cross axes, four different quadrants of potential actions emerge.

By crossing the axes each of the four quadrants can create different possibilities as illustrated by naming each quadrant as a scenario. There are four scenarios depending on the circumstances. But there are also variations should one be positioned at different points along one or other of the axes. There are also degrees by which any scenario is emphasised depending on where the axes intersect with each other. If the vertical axis were to be moved to the left toward the cold extreme of the horizontal axis there the choices are even more stark. This is a straightforward example.

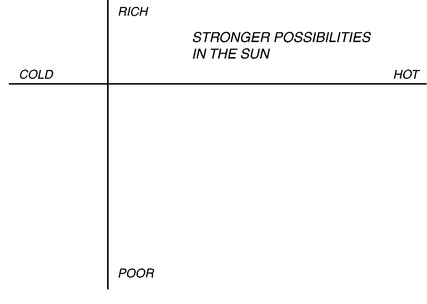

The issues identified in the earlier exercise in this chapter involving staff would provide an abundance of issues for this simple cross-axes exercise. Indeed the exercise can be and shoud be done for a variety of issues which are straining the organisation. By crossing issues which might be providing tension in the organisation, potential stories of different futures can emerge. The stories may in turn lead to the investigation of solutions or may just lead to further stories. At this stage, however, it is so important to keep minds open to different perspectives, to different outcomes, especially those which had not been entertained previously.

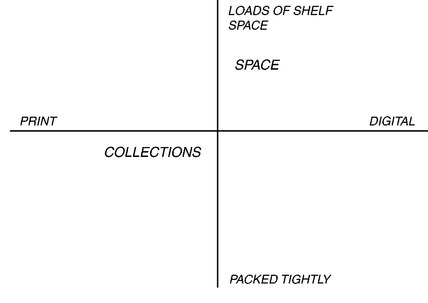

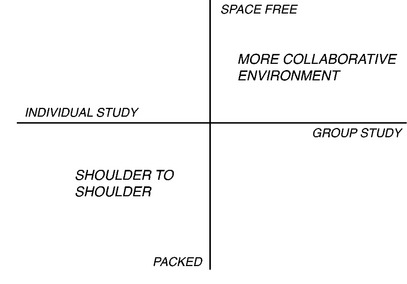

A more relevant library example might be as outlined in Figure 4.3.

There are two issues here with choices to be made. Each quadrant will begin to tell a different story. From our work in Chapter 2 we began to make predictions as to where we might be on the print–digital continuum in a certain period of time. If we believe that our library will have moved very significantly toward digital delivery the library can target different positions in relation to the existing position and future chosen positions. In this way, the relevance or purposing of the physical building might be open for discussion.

The Physical Library might then develop a different purpose, a similar purpose or even a more radical one as a learning or community space. The purpose of a Library Scenario in this quadrant might be revealed through discussions around the disruptive technologies and other options within the broader organisation of which the library is part. But it begins to draw a story of where the library is heading. If, however, the library’s research places it in the quadrant described as Digital-Tightly Packed, then the Library’s story or future scenario would be quite different. This might see a strong move to digital delivery of content but a very strong legacy print collection which needs to be managed in harmony with the digital future.

Choices with timeframes in mind

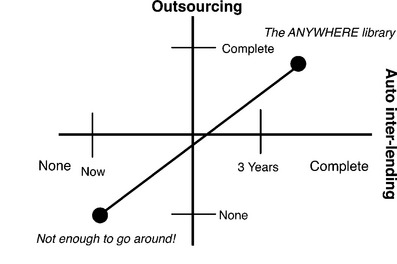

To extend the scenario creation process we can introduce the element of time. In this, two critical issues for the library have emerged as outsourcing, or not, and personal service/auto-mediation. These two issues are likely to be highly relevant in the current financial, technological and education climates. The financial environment is such that money for libraries might be tight and economies in the library operations are being sought. The outsourcing issue might be one issue while there could be a number of others. The concept of personal service versus auto service could be an issue arising from financial pressures but could also, as discussed in Chapter 3, be a desirable possibility as Web 3.0 technologies come more and more into play. Web 3.0 is broadly termed the ‘Semantic Web’, where technology will be more intuitive in interpreting user requests and retrieving relevant information. Web 3.0 offers huge potential for libraries and equally interesting threats to the future of the library service as we currently know it. So it is an issue which must be addressed. Where does your library wish to be positioned if this possibility is to happen?

In this example, the Outsourcing–Auto-mediation quadrant might be described as the Anywhere Library. In this scenario, the library might not have a physical presence but be very reliant on emerging Web 3.0 technologies, enabling the user to drive the information system themselves. Equally, one can apply time and status pointers to both of these axes which will also drive the shape of the scenario. By indicating that we are currently well away from a full auto-mediated situation and that in three years the library would still have a long way to go, two aspects are made clear. One is that the scenario approach has enabled the library to consider a future that might have otherwise been discarded or not seriously considered. It can still be allowed for in planning terms, in organisational and structural terms. Two, it gives the library a purposeful direction but with options. The library in these scenarios does not have to commit to a total outsourcing or auto-mediated approach. It is able to signal where it believes the current and future situations might be while allowing for these possibilities. A story and a vision will emerge, rather than just struggling along. A clear strategic direction and future can be seen to emerge from this technique. A way of making sense of these projections would be as shown in Figure 4.7.

As we progress this exercise it can become more and more complex in terms of the strategic issues and the stories which emanate from the quadrants. By combining the axes, the timeframe and the potential to move from one strategic state (Not enough to go around) to another (The Anywhere Library), new possibilities open up for the organisation.

This axis-with-time exercise can be used in local or departmental planning scenarios as well. The inter-lending department might want to think independently about their own positioning. The acquisitions department might wish to do something similar. The exercises of the issues, the simple and then the more complex axes work well in this local planning environment as well.

Alternative scenarios

Using this ‘axis of uncertainty’ technique, and a number of the issues arising from the earlier exercise, new insights can be developed. So there can be multiple axes exercises developed, only with different issues. The juxtapositioning of even previously unassociated issues can lead to interesting possibilities. The researching of the resulting ‘scenarios’ in the quadrants will unleash new possibilities. This is entirely natural and indeed helpful. Using these techniques and outcomes helps to reveal that, as the scenarios raise the level of the debate from issues to broader scenarios, a range of choices still exist. Organisations under pressure or in crisis often succumb to the most ‘obvious’ solution. A consortium organisation losing its income streams could face the obvious direction to downscale, but with intelligent scenario insights, and a little in the way of reserves, can choose to grow instead of shrink. This is a case of what Chesterton observed earlier in this chapter: go away and do the opposite. The library facing the need to change its basic business may choose to become a more relevant Resource Centre instead of maintaining its strong heritage and fundamentally changing the nature of the library business model. The most obvious is not always the most desirable. The most obvious is certainly not necessarily the most effective and sustainable for the long term.

The solutions are often wrapped in the form of paradoxes and paradoxes are contradictions.4 Being aware of this phenomenon can begin to allow alternative solutions to be entertained and even developed. The position of paradox often blinds us, restricting our position from noticing what is possible. We can too easily reject the idea without giving it real consideration. To grow when we should be shrinking is a contradiction and we resist the adoption of this plainly absurdist position. It seems to be illogical; too illogical. To be not following the world in fashion or in practice is a contradiction and therefore difficult to entertain, let alone develop. To entertain a library without books is so against the instinct as to be extremely difficult to grasp. It is not that these contradictory positions are necessarily correct but by examining them the germ of a good scenario may be grasped and developed. So paradoxical positions can be beneficial. They allow the mind to think about things which we would not normally allow ourselves to think about. This is the kind of thinking which we want to achieve.

The excellent book Management of the Absurd by Richard Farson5 delves into the issues of paradox and the absurd. Time and again he makes the point that we, as humans, think and say that we want to do something but in the end we find the possible changes deeply threatening. He talks about how relatively easy it is to develop creative ideas but shows that it is so much more difficult to accept and implement the ideas. ‘The fundamental problem with creativity is that every new idea requires the manager and the work force to undergo significant change.’6 ‘Real creativity, the kind that is responsible for breakthrough changes in our society, always violates the rules.’7 Creativity and new ideas are often negated by the fear of being different. If we are looking for breakthrough change, the earlier chapters in this book highlight that change will happen to us if we do not act; it will happen quicker than we might even rationally imagine. Change by increment or gradual change will waste the potential of an organisation to contribute and to develop. The changes need to be decisive, not immediately in action, but especially in a chosen direction.

This methodology can build on the Axes of Uncertainty as well as the tools which were developed in Chapters 2 and 3. A great deal of input can be gained from the research and insights gained through those exercises. This methodology utilises group and workshop activity to take the input and individual insights to challenge each group to develop three broad-brush scenarios which are alternative scenarios.

Imagination

Scenarios are an invention of the imagination. They are plausible stories about the possible futures for our libraries. The use of our imagination is crucial to give the stories a real and inviting flavour. The use of imagination also allows the introduction of interest and excitement to the picture being drawn of the future or the great story being written. Imagination breaks us out of the humdrum of ordinary life and into a space which is different, interesting and inviting.

Having heightened our sense of imagination we have to maintain in the stories we tell a certain level of plausibility. This does not deny us the chance to think ‘outside the box’! The scenarios can and should be imaginative, plausible, stimulating and challenging. The scenarios will be about people, information and spaces (or no spaces) but they will evoke in the reader a real sense of what could be and how they may be able to identify themselves in that space or place. Not all the scenarios will be equally attractive to all the readers but this is where the debate can begin in earnest and the use of good imagination will help us get there.

Unexpected or surprise futures

This position is the logical extension of the first two approaches to scenario construction. It is the ‘most unlikely’ event strategy. The newspapers are littered with life-threatening events affecting the lives of us and our fellow citizens. Many or most of these events are unpredictable. They always happen to someone else. They are unexpected; they are often totally abnormal or beyond the range of our imagination or expectation. We do not go out of our homes and expect to be hit by a truck or to have the building we are living in collapse. As such we do not allow for them in our normal planning; in our normal lives. We do not allow ourselves to think of the ‘unthinkable’. Therefore we do not allow for it in our planning. Planning for the attacks of 9/11 in New York was so far outside the range of possibility, it was not planned for by government officials. It was a less than 1 per cent risk situation. It was the most extreme scenario and, as such, was never taken heed of. The American Vice President was so shocked with the events of 9/11 that he turned the risk approach for American national security on its head and actually planned for the 1 or 2 per cent events. This, of course, is a hugely expensive approach but it was a decision which they felt was necessary.

Does planning for library and information service futures involve planning for the 2 per cent possibility? Perhaps. Perhaps not. But the assessment of risk is a strong reminder that there are events which are outside of what we allow ourselves to think of but are important to at least consider. Where we have talked earlier in this chapter of alternative scenarios and other variations, so it is crucial to consider an extreme scenario. It is timely also to remember that we do not have any one future; we have many. So at this stage we need to have a range of options or scenarios. The scenario which we do not allow ourselves to think of can sometimes provide direct stimulation and vital input for a more realistic final scenario.

So many writers have in recent years prophesised the death of the library or the death of the book. The book by Richard Watson, Future Files,8 has presented an extinction timeline from 2000 to 2050. In this he predicts a number of things. By 2019 he predicts that libraries will be extinct. By 2020, he predicts that copyright will be extinct. By 2023, he predicts that the desktop computer will be extinct. The scenario in which all three of these predictions come true would indeed be a scenario with severe consequences for our planning.

What would we do if indeed copyright were to be abolished from the statute books? It would signal a wholesale change in the way we understand the written expression of thought or fiction. What would we do?

To entertain the extinction of libraries is much closer to home. It is absurd to our being but it has now been openly speculated about. It is talked about and even accepted as a reality soon to occur. Inevitable, say some. This is the extreme scenario. It is perhaps a very low risk as far as our thinking is concerned but it just could become a reality. What would we do?

Keeping options open

The intention of the discussion in this chapter has been to create options; to create different scenarios and to avoid leaping to a conclusion as to the best or most likely future. To leap too early is to destroy all the thinking which has been examined in the earlier chapters and the array of possibilities which are always before us. This chapter has also sought to begin the process of creating options, of naming some of these options as potential scenarios and of allowing the extremes to enter the debate and thinking.

We are now well positioned to get the best out of our people, our users, our stakeholders in the next chapter.

1.Available at: http://thinkexist.com/quotes/robertjritz/ (accessed on 20 July 2010).

2.O’Connor, R. (2009). ‘Word of mouse: Credibility, journalism and emerging social media’. Joan Shorenstein Center on the Press, Politics and Public Policy. Available at: www.hks.harvard.edu/presspol/publications/papers/discussion_papers/d50_oconnor.pdf: 10 (accessed on 20 July 2010).

3.Chesterton, G. K. (2003). Quoted In Laura Moncur’s Motivational Quotations. Available at: www.quotationspage.com/quote/1923.html (accessed on 20 July 2010).

4.A paradox is a statement or group of statements that leads to a contradiction or a situation that defies intuition. Paradox as defined in Wikipedia. Available at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paradox (accessed on 12 February 2010).

5.Farson, R. (1996). Management of the Absurd. New York: Simon and Schuster.

6.Ibid.

7.Ibid.

8.Watson, R. (2008) Future Files. London: Nicholas Brealey Publishing.