6

Urbanizing the Inter-organizational Information System

6.1. Inter-organizational territory

As we saw in Chapter 4, a territory implies the existence of borders. These borders are regularly called into question by transformations of the territory (and/or of neighboring territories). Consequently, the spatiality of territory is generally perceived as a build-up of multiple levels. Ongoing globalization processes call for a review of territorial boundaries and levels.

We might think that the concept of territory is in a way obsolete. Territory is indeed challenged by the development of networks. People, organizations, materials and capital are thus becoming increasingly mobile. This mobility reduces the scope of the concept of a territory with specific resources. However, borders have not disappeared completely. They are coming back in an even more aggressive way, because borders are becoming the territory’s one remaining institutionalized element. Consequently, a territory can become a guarantor of identity. As such, movements in the territory are supposed to be checked at the border. At the same time, differences within a territory are eliminated for the sake of unity.

Thus, territories change their shape when seen at different times and from different viewpoints. The question of the correct distance [JAI 09] thus becomes crucial in going beyond the proximity and locality of the traditional concept of territory.

Power struggles are therefore no longer limited to the company’s internal borders, but extend further and further along the external borders. New elements are added to justifications of the organizational form. This form may no longer depend solely on the quasi-automatic rules linked to transaction cost in relation to its environment [WIL 98]. This is how an organization’s identity changes. The territorialization process of companies [AME 88, GAF 90] is becoming weaker, because businesses are interacting more and more globally. Territorial trajectories are more uncertain, because the stakeholders who shape these trajectories are more mobile and less attached to and dependent on a certain territory. Global players choose their territories and their locations on a global scale. Thus, the company’s territory goes from a status of fact and confinement to a status of internalized parameters and strategic choices. Meso-economic theories combine with micro-economic theories to explain this new situation and put forward operational guidelines.

6.1.1. Inter-organizational territories and the value chain: the sectorial chain

Development of the definition and structure of the production operations of the firm and its territory are characterized by an adjustment to the management systems on two levels: internal and external [PAC 06]. The first level of adjustment to the management systems is internal. We see growth in production and networking and a change in the approach taken by the firm, with some tensions between process logics and function logics. The process logics written into the software have to cope with other external partners, which in some cases leads to redesigning the business processes of several organizations together.

It is in this context that Porter [ROP 85] puts forward the value chain model.

The starting point of the value chain, according to Porter, is the company’s business units. At this level of analysis, the value chain is thus all the steps that determine the capacity of a business unit to gain a competitive advantage. Competitive advantage is defined as all the characteristics or attributes of a product that gives the business an edge over its immediate competitors. This edge, also called the “value”, translates in concrete terms into how much customers are prepared to pay for the product. When viewed in this light, the value chain becomes an instrument for the company to build a competitive advantage. Doing so hinges on the company’s ability to position itself within the sectorial chain, i.e. the business activity sequence that transforms raw materials into finished products.

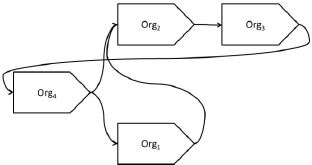

Figure 6.2. The business sector as an inter-organizational territory of a series of Porter value chains

The quality and sustainability of the created competitive advantage depends on the choice of activities kept in house. These have an impact in terms of cost (if the company is pursuing a price leadership strategy) or quality (if the company is aiming for a differentiation strategy). These activities are split into primary activities and support activities. Primary activities directly compete with the physical creation and sale of a product. Support activities are there to back up the primary activities.

The value chain helps us understand the importance of internal coordination within the company and external coordination with the other organizations involved, from the extraction of raw materials to consumption of the finished product. It is a sector-driven approach that emerges through an analysis of the value chain. This calls into question the classic perception of territory. The sector can be defined as a set of products or services and its producers, competing to serve one market. Globalization, and especially the very significant reduction in transport costs and transaction costs, is resulting in more and more business sectors making their arrangements on a worldwide scale. Production processes become fragmented, with the companies involved constantly making choices between internalization and outsourcing of production and between integration and spatial disintegration. Porter shows that there is no reason why all activities should be carried out by the same company and he confirms the end of the vertical integration logic of multi-divisional companies.

Figure 6.3. The ecosystem as an inter-organizational territory in the value network

These permanent reconfigurations are proving disruptive to territorialized stakeholders who do not have the same flexibility. The territorialized stakeholders then have to work directly to attract organizations and specifically major investment groups.

Figure 6.4. Value network of a pharmaceutical company. An example of a value network in the pharmaceutical sector. Adapted from Verna Allee, Journal of Business Strategy, vol. 21, no. 4, July–August 2000

6.1.2. Inter-organizational territories and the value chain: the ecosystem

The second level of adjustment for management systems is linked to the birth of business ecosystems [PAC 06]: more intensive production and inter-business communication resulting from the proliferation of industrial cooperation agreements. With the rejection of the integrated vertical, hierarchical vision, new horizontal and non-hierarchical structures based on the notion of districts or local networks are gaining ground. The idea is to build peer-to-peer networks (between equals) based on cooperation and information sharing. Even though companies have no structural links between them, they all contribute to the development of the same territory. This contribution has been theorized in the stakeholder concept [FRE 10] which recognizes the existence of interdependent relationships between the company and the various groups that make up its environment with which it interacts.

These organizational networks should make the territory competitive in a fragment of a production process in a certain sector, and thus should potentially be able to generate cumulative growth dynamics. In the absence of full mobility of people and capital, certain activities cluster together on territories that offer specific advantages. In competition, territories apply the same strategies as companies: price strategies, differentiation strategies and/or focus strategies.

Analysis of the benefits generated by organizational networks has been facilitated by the value network theory [CHR 16]. Going beyond the value chain, the value network is an analysis framework for economic activities that defines the distribution of resources both within and across organizations. The nodes in the network are individuals, activities or businesses, and these nodes exchange tangible deliverables (e.g. physical goods) or intangible deliverables (e.g. knowledge) between themselves. The network approach helps us to appreciate the interdependence of the stakeholders in a network. Seeing the full picture helps explain the value of products and services provided, and thus to go beyond the logic of the value chain and its linearity [STA 98].

6.2. Inter-organizational territory of the information system

The way we view the information system changes with this new perception of the territory. Information systems are thus seen as forming linkages between organizational functions and the hierarchical levels that structure them, but not only that. Globalization also leads information systems to create a new linkage between functions and external partners [CAR 10].

Figure 6.5. The inter-organizational territory of the information system as internal linkages between functions and hierarchical levels and external linkages between functions and external partners

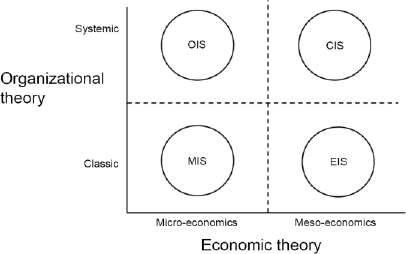

Visualizing the territory at the meso-economic level calls for a change in perspective. The information system can no longer be viewed as exclusively internal (represented by MIS and OIS forms) or external. It is both at the same time. The micro-economic theories in Chapter 4 are compounded by meso-economic theories which identify two new categories of information system: the extended information system and the cooperative information system. In total, this taxonomy of information systems, along two axes (economic theory and organizational theory), provides a typology with four categories of business information systems for a theoretical and empirical overview of the development of information systems and their territory [ALB 12]. The difference between an extended IS and a cooperative IS is both theoretical and operational.

Figure 6.6. A taxonomy of business information systems, according to mobilized theories [ALB 12]

6.2.1. The extended information system

The extended IS is the information system of “classic” meso-economics. It principally comes from the work of Coase [COA 37] and Williamson [WIL 98] who accepted the need to re-examine the principle of pure and perfect market competition between companies. This re-examination includes the introduction of a new concept: interfirm strategic relationships. These strategic relationships are conceived as quasi-automatic adjustment mechanisms within a market, which are triggered in line with transaction costs.

Figure 6.7. The archetype of the extended IS in a continuation of the sectorial logic

However, these strategic relationships create a new territory, a third arena of resource allocation, beyond the two classic arenas of micro-economics: the firm and the market. In this new conceptual framework, the information system will extend, quasi-automatically, like the strategic relationships it translates, to meet the new requirements for inter-organizational alignment, adjustment and coordination [ALB 12]. In a case where outsourcing a strategic activity would reduce costs, the firm will establish both a strategic relationship and a market relationship via extended information systems. The extended information systems can be seen as the operational translation in IS terms of the economic need to outsource certain activities without losing operational and strategic control. The extended information system shows that companies can call on an electronic data interchange (EDI) to handle the outsourcing of their activities in a space where control is retained. The extended information system thus appears as the MIS of a new meso-economic territory exceeding that of the micro-economic firm, but where each firm keeps its autonomy and its control centrally.

6.2.2. The cooperative information system

The cooperative information system (CIS) is the information system of systemic meso-economics, a double departure from the classic theory of the firm, both in terms of organizational theory and in terms of economic theory [DEB 89]. For Aoki, the principles of perfect competition in the market and economic calculation are not sufficient to understand the motivations of stakeholders and the configurations observed on the ground. The issue of outsourcing cannot be reduced to an economic calculation that could be resolved simply by market mechanisms, but needs an additional element. Aoki calls this a relational rent. He defines this as the surplus value created by two or more stakeholders who cooperate to overcome the problems of asymmetry of information in an uncertain universe. In other words, the value chain can be accomplished in a long-term industrial cooperation network with other firms to reduce uncertainty and information asymmetry [AOK 86, COH 90]. Aoki views the firm as an open socio-technical system where business strategies are based on industrial cooperation agreements and outsourcing strategies, and they define and structure networked organizations that jointly implement a productive project, in other words business processes.

Figure 6.8. The archetype of the cooperative IS in a continuation of the ecosystem logic

Table 6.1. The differences between vertical and horizontal networks

| Network type | ||

| Perspectives | Vertical | Horizontal |

| Level of control | Ability to define the composition of the final product and the improvements that create value | Interdependence between participants |

| Lever | When the final product is successful, one company benefits more than the others | All participants can benefit from the success |

| Cooperation | Contained within each company | Trust and cooperation between participants are fundamental |

| Focus | Efficiency | Flexibility |

| Risk level | High risk of disruption | Risks mitigated by network optimization |

| Capital requirements | High capital requirement to create, produce and distribute the final product | Lower requirements, because others can own some of the assets needed to create, produce and distribute the final product |

| Attitude to partners | One company operates to the detriment of other companies | Assisting other companies strengthens the business providing the assistance |

The Japanese form (J-form business) is given as a model for the networked business [AOK 92]. J-form is an alternative to what Aoki calls the American form (A-form), within which he includes the unitary form (U-form) and the multi-divisional form (M-form). The J-form firm is particularly characterized by an extension of its territory resulting from the phenomena of interfirm cooperation in the implementation of business processes. This industry cooperation can constitute a network of firms with predominantly vertical or horizontal relationships. Relationships are vertical when a leader firm builds a network with business partners upstream and downstream of its business activity (Vertical Network Firm). Relationships are horizontal when a company builds a network with members of the same business sector, complementing each other and pursuing a common goal, with no recognized leader (Horizontal Network Firm) [AOK 86].

The J-form offers a hybrid form of firm, resulting from strategic relationship strategies [ARL 87] based on the principle of a value creation network that does not necessarily belong solely to one firm.

Translating this theoretical proposal into the information system leads to the creation of the CIS. Thus, the CIS resembles an “OIS”, empowered by a new meso-economic territory that exceeds that of the micro-economic firm.

Table 6.2. A summary of inter-organizational value creation. Value chain and value network and their information systems. Adapted from [KUM 96]

The CIS can also justify itself in terms of the objectives of the Information Society:

“We recognize that building an inclusive Information Society requires new forms of solidarity, partnership and cooperation among governments and other stakeholders, i.e. the private sector, civil society and international organizations. Realizing that the ambitious goal of this declaration both at national and international level – bridging the digital divide and ensuring harmonious, fair and equitable development for all – will require strong commitment by all stakeholders, we call for digital solidarity, both at national and international levels” [ITU 04].

6.3. Alignment and representation of the inter-organizational information systems territory

The question of alignment must be reconsidered with these changes in the territories of the organization and the information system. We are entering the territory of meso-economics and thus of the extended enterprise. Information systems alignment here has to do with the linkage between the internal (firm’s) network and the external partners.

Table 6.3. A perspective of the territories of the organization and of the information system (inspired by Bidan [BID 06]) and of the inter-organizational territories of the information system

| System source | Organization | Information system | ||||

| Territory | Of the firm | Of the information system | ||||

| Economic theory | Micro-economics | Meso-economics | ||||

| Organizati onal structure theory | Classic functional | Systemic procedural | Classic functional | Systemic procedural | Classic functional | Systemic procedural |

| Typology | Functional | Systemic | MIS | OIS | EIS | CIS |

| Elemental component | Function | Process | Business application | Module | Electronic Data Interchange | Network node |

| Architectu re | Functional per silo | Cross-disciplinary per process | Standalone applications | Modular | Hub-and-spoke | Peer-to-peer |

| Referent | Function mapping (organizational chart) | Business process mapping | Applications mapping | Access mapping | Value chain mapping | Value network mapping |

| Formalizat ion | Procedure | Process | Program | Configuration | Proprietary standard | Open standard |

| Disseminat ion mechanism between units | Hierarchy | Process manager | Interdependence delayed monodirectio nal flow | Automation monodirectio nal real time flow | Automation bidirectio nal real time flow | Automation multidire ctional real time flow |

While the alignment of the information system broadly reflects the questions asked in the context of micro-economics, since every company has full control across the scope of its information system, the issue is completely new in terms of systemic organizational theories. The information system issue is no longer centered on a standalone system, but is designed and created to be in constant interaction with its ecosystem. Consequently, the interoperability issue becomes central. The information system is thus perceived as a set of Lego building bricks, where frameworks of interpretation must be found to ensure the clarity and relevance of the whole.

Territorial representations become more complex, because the company integrates into them items that exceed their borders and are controlled by other organizations. More people are involved and the choice of common rules and a common language for communicating about the information system has to be discussed and resolved.

6.4. Urbanization of an inter-organizational information system

In the last chapter, we presented the urbanization of the information system as a process used in large organizations to act as a framework for the transformation, rationalization and improvement of the business information system. With the increasing pervasiveness of multistakeholder debates and initiatives, information systems urbanization must move forward as well.

In the same way as classic urbanization changes and urbanism along with it, the urbanization of information systems must also change. A city becomes increasingly populated, but due to a seesaw effect, the city becomes increasingly dependent on other territories that supply it with new arrivals and reabsorb the flow of leavers. In addition to the urbanism plans that cover the municipal territory, there are other instruments such as, in France, the Territorial Coherence Program (SCoT – Schéma de Cohérence Territoriale). This document is created by several independent municipalities, which form a union to agree on a territorial plan covering several municipalities with the aim of coordinating all policies relating to housing, mobility, business development, environment and landscape.

Similarly, the urbanization of an information system is no longer a simple process aimed at creating an information system capable of informing and supporting the company’s strategy, but rather a process aimed at creating a number of information systems capable of informing and supporting the strategies of several companies in extended, distributed, cooperative organizational frameworks, or in other words open frameworks.

In this inter-organizational perspective, IS governance takes on new meaning, because there is no one single company executive in charge, but many peers who must together steer the urbanization of their information systems. The top-down approach to urbanization loses in efficiency, because there is no longer a company executive that can easily impose a strategic direction plan on all stakeholders. The bottom-up approach becomes relevant, since this is based on pooling and sharing and involves dialog with the company’s internal and also external stakeholders.

The chief objectives of the urbanization of an inter-organizational information system remain the same. They do, however, develop some specificities. In order to develop an understanding of the existing information system, the repository will be inter-organizational and will cover several information systems belonging to several organizations. Similarly, the mapping will give a visual representation of several information systems. In these contexts of inter-organizational urbanization of information systems, representations may have coarser information systems granularity. Rather than focusing on functions and function blocks, the mapping will be more oriented towards the representation of districts and areas.

In terms of defining the target information system and associated trajectory, the target information system is no longer that of one company, but those of several companies. Consequently, the trajectory must emerge from a convergence of the strategies of several organizations. The various organizations must reflect separately and together in order to decide how the information systems can serve the strategic objectives of each company in synergy with the other companies, and how the inter-organizational information systems can facilitate the pursuit of these objectives. As in an internal urbanization process within an organization, the quest for rationalization and simplification of the information system’s structure will be pursued in the inter-organizational urbanization process. However, in this case, rationalization and simplification must be measured at the wider territorial level, which can mean sub-optimal local solutions for the sake of maximum global optimization.

The two main rules of information systems urbanization, weak links and strong ties, still apply in the inter-organizational context. In this case, planners must integrate function blocks coming from other organizations. They must also recognize that each company’s function blocks should be able to effectively and simply communicate with those of the other companies.

Faced with the exponential growth in the number of stakeholders, the IS management committee plays a more and more central role in building a common space for cooperation. The development of technology, especially cloud computing, IT standards, free software and open data, has done a great deal to support and contribute to the opening up of companies to their stakeholder networks. These will be discussed in sections 6.4.1, 6.4.2, 6.4.3 and 6.4.4.

6.4.1. Cloud computing

Cloud computing is the use of the computing and storage capacity of remote servers via the Internet, on demand and on a self-service basis. Usage is agreed by subscription between the provider who arranges access to the servers and the customer who uses the service. From the customer’s point of view, this service is ready (or nearly ready) for use as soon as the subscription is taken out, regardless of the size of the request and the service selected from the provider’s catalog. The client pays a regular subscription to the service, usually in line with usage requirements. This is calculated and forecast from the number of users, the computing capacity needed, the volume of storage used, the bandwidth occupied, the service reliability level, etc. Providing the service over the Internet ensures a significant opening up of the service. This is reinforced by the use of international standards and protocols and a wide range of devices and networks. The provider, on their side, has the advantage of being able to pool their IT resources. Thus, the same server can potentially be used by several customers at the same time in line with fluctuations in demand. If demand increases, the provider can use multiple servers in parallel to meet the requirements of one customer, in a way that is transparent and instant for the end customer.

These common features are then offered in different packages, according to target group:

- – public cloud, when the service is made available to the general public;

- – private cloud, when the service is made available for the exclusive use of a particular organization. This organization will have more room for maneuver in handling resources available in the Cloud;

- – community cloud, when the service is made available to a group of organizations, by the same group of organizations, as part of a pooling of resources;

- – hybrid cloud, when the service combines both private and public cloud in order to perform different functions.

One important difference in the package is which main service category it falls into:

- – Infrastructure as a Service (IaaS). This means the provision of access to virtualized computers on which customers can install an operating system and applications;

- – Platform as a Service (PaaS). This means the provision of access to computers on which an operating system chosen by the client has already been installed. Based on this operating system, the customer can install applications;

- – Software as a Service (SaaS). This means the provision of direct access to specific applications, with the supplier being responsible for managing the computers and the operating systems required to run the application.

| Internal model | Infrastructure as a Service (IaaS) model | Platform as a Service (PaaS) model | Software as a Service (SaaS) model |

| Business application | Business application | Business application | Business application |

| Data | Data | Data | Data |

| Database software | Database software | Database software | Database software |

| Operating Systems | Operating Systems | Operating Systems | Operating Systems |

| Virtualization layers, platforms and internal networks | Virtualization layers, platforms and internal networks | Virtualization layers, platforms and internal networks | Virtualization layers, platforms and internal networks |

| External partners and networks | External partners and networks | External partners and networks | External partners and networks |

Legend: Organization’s responsibility (normal text) Shared responsibility (italics) Supplier’s responsibility (bold) |

|||

This offers great flexibility to customers. Small- and medium-sized companies especially have the option of gaining access to services previously reserved for large companies because of their traditionally high entry cost. However, these benefits have to be offset against, for instance, the difficulties frequently encountered in getting out of a cloud computing contract that generates customer dependency on the provider.

This introduction to cloud computing gives an insight into its impact on the information systems territory and on its urbanization. The territory of the information system is indeed changed, because traditionally the company’s servers used to be within the company and its information systems management directly controlled their operations. With cloud computing, the information systems territory moves further away to the leased remote servers, without necessarily knowing: where exactly these servers are; which servers, among the thousands housed in the same data center, process and store which company data; what happens at the service provider’s premises; what a service provider does with the company’s data; who has access to these data; what would happen if the service provider were to go out of business; which country’s law applies; or what security is in place to protect the data.

Consequently, information systems urbanization is impacted by cloud computing. As we have seen, the urban planning of a city steers the construction of various public facilities and private buildings and their development over time. The urbanization of information systems picks up this logic and applies it to information systems design and development. However, cloud computing conceptually changes the object of information systems urbanization. With cloud computing, there is a shift from a logic of property, purchase and ownership of hardware to a service logic, which is part of a broader and deeper tertiarization of the economy. For the information systems planner, cloud computing leads to the vacating, in part at least, of certain levels of the information systems, depending on the category of services subscribed to.

6.4.2. Computing standards

In computing, establishing a dialog between several partners requires the use of a common language and common rules. With the expansion of telecommunications, multinationals and international trade, the need to create shared languages and rules for information systems has led to the progressive development of several IT standards. Since the late 1960s, American companies have been looking for a way to make better use of their computer equipment and telecommunication networks. These companies set up the Transportation Data Coordinating Committee, whose findings formed the basis of what was to become today’s EDI. The American National Standards Institute (ANSI) then established its Committee X12, responsible for establishing inter-industry standards for the EDI, to extend the Transportation Data Coordinating Committee’s outcomes to other economic sectors. The ANSI X12 standards were published in 1985 and purported to be applicable to all business sectors. In parallel, the US joined with their European partners (in France, for example, the retail sector had developed the EAN standard and the automotive sector had developed the GALIA/ODETTE standard) to create a set of international standards. The international standards EDIFACT (Electronic Data Interchange For Administration, Commerce and Transport) was released in 1987. EDIFACT offers a set of standards and guidelines for the electronic exchange of structured data between independent information systems.

In defining standards of interoperability for the development of information systems at the international level, the International Standards Organization (ISO) plays a central role. A great many standards have been created since the early 2000s to standardize formats and for the exchange of data between information systems. These standards must continually evolve to keep up with technological developments and business practices. The recognition of new technologies and new practices such as ISO standards has significant economic repercussions. For example, every office suites user is impacted by standards relating to file saving formats (doc, docx, odt, rtf, etc.).

Table 6.5. Indicative (but non-exhaustive) list of ISO standards for information systems standardization

| ISO standard number | Topic covered |

| ISO 2709 | Information exchange format (ISO/DIS 2709) |

| ISO 7498 | Open Systems Interconnection (OSI) standard for communication between computers in seven layers |

| ISO 10303 | Standard for the exchange of product model data |

| ISO 14048 | Formats for electronic data interchange |

| ISO 15504 | Framework for process evaluation |

| ISO 19005 | Portable Document Format (PDF) designed for long-term archiving of information |

| ISO 19503 | Data exchange standard based on XML |

| ISO 21127 | Benchmark ontology for the exchange of cultural heritage information |

| ISO 26300 | Open Document Format for Office Applications data format for office applications |

| ISO 29500 | Office Open eXtensible Markup Language (XML) format for office applications |

ISO standards have also contributed to the development of the Internet. The EDI’s origins lie in the business environment, while the origins of the Internet are more military and academia-based, notably at America’s Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA). In the 1960s, the original intention was to design a computer network within the agency, the ARPANET. In the 1970s, the IT protocols TPC/IP were designed to enable other IT networks to connect to ARPANET, thus introducing network interoperability and the creation of a network of networks: the Internet. In the 1980s, more and more institutions, universities and research centers in the United States adopted TCP/IP protocols and linked to ARPANET. In the early 1990s, the network was opened up to commercial traffic. This was the decade when the Web, written in HyperText Markup Language (HTML), and its base protocol, HyperText Transfer Protocol (HTTP), were developed. Web services are certainly the most commonly used protocols up to the present day to interconnect stakeholders and applications developing in separate environments but contributing to the implementation of shared processes. The EDI has also developed and attached itself to Internet standards and protocols.

| Layer | Examples of protocols |

| Application | HyperText Transfer Protocol (HTTP), Telnet, File Transfer Protocol (FTP), Simple Mail Transfer Protocol (SMTP), Trivial File Transfer Protocol (TFTP), Domain Name System (DNS), Internet Message Access Protocol (IMAP), Post Office Protocol (POP), Secure Shell (SSH) |

| Transport | Transmission Control Protocol (TCP), User Datagram Protocol (UDP), Stream Control Transmission Protocol (SCTP), Real-Time Protocol (RTP) |

| Internet | Internet Protocol (IP) version 4 (v4), IPv6, Internet Control Message Protocol (ICMP), Internet Group Message Protocol (IGMP), Routing Information Protocol (RIP), Address Resolution Protocol (ARP), Reverse Address Resolution Protocol (RARP), Exterior Gateway Protocol (EGP) |

| Network access | Ethernet, Global System for Mobile communications (GSM), Universal Mobile Telecommunication System (UMTS), Token-ring, Point-to-Point Protocol (PPP), Digital Subscriber Line (DSL) |

6.4.3. Free software

As we saw in Chapter 2, free software is software that can, technically and legally, be used, inspected, modified and disseminated via copies [STA 10]. These rights may simply be available if the software is in the public domain (such as the SQLite database management system), or if these rights are protected by a license that is itself governed by copyright law (like the GNU/Linux operating system). Free software is a cooperative alternative to proprietary software in that it promotes the freedoms to use, inspect, modify, copy and disseminate developed solutions.

Open source, i.e. making the software source code available, is a necessary condition for software to be regarded as free software, but open source is not in itself sufficient to make it free software. It is more a method of development through the reuse of the source code, than an information system in itself.

Table 6.7. Differences in rights between the main types of licenses

| Differences in rights between the main types of licenses | Type | ||||

| Free software | Freeware | Shareware | Proprietary | ||

| Rights | Use | Yes | Yes | Limited by license | Limited by license |

| Inspection | Yes | No | No | No | |

| Editing | Yes | No | No | No | |

| Copying and dissemination | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | |

Intensified development of free and open-source software is both an indicator and a facilitator of this collaborative movement towards shared spaces where stakeholders are less and less constrained by interoperability problems. Free software is now widespread within organizations, especially charities and government departments. Many government projects have in fact supported the development and distribution of free solutions.

6.4.4. Open data5

The CIS has certain limitations relating to the difficulty of protecting data and information in line with copyright – and more generally in line with intellectual property rights – because data are not considered to be original creations. Information systems managers therefore prefer not to disseminate them so as not to allow certain competitors to benefit from them. This inaccessibility of data can limit the dissemination of knowledge in society and our understanding of the reality around us, and impair the right of citizens to be informed.

However, the legal protection for databases was introduced in Europe through the Directive 96/9/CE of March 11, 1996 and was transposed into French legislation in the law of July 1, 1998. It is a sui generis protection of the investment that the owner of the database had to make in order to structure the database, fill it with content and make it presentable externally. Databases are thus protected for 15 years after their creation. Consequently, the author of the database may prohibit unauthorized extraction and/or reuse of the contents of a database that would be contrary to the legitimate economic interests of the author of the database. In practical terms, the data available on websites can be used on a one-off individual basis, but the extraction of all the data stored in the database feeding the website is not permissible. Similarly, an obligation to open up the data comes from the right to information. This right generally refers to freedom of access to public authority documents (Law No. 78-753 of July 17, 1978) and of the duty to inform the consumer about the nature of goods for sale (art. L 111-1 and L-221-1-2 of the Consumer Code).

Some administrative bodies have thus implemented information systems enabling access to data collected by public services and to information resulting from the processing of collected data (e.g. the French government through the www.data.gouv.fr website). In the private sector, some organizations have gone in the same direction towards opening up their data (e.g. the company Enel through the data.enel.com website). Even one of the world’s four largest audit and consultancy firms, Deloitte, is inviting companies to open up their data to developers and to the public, because this creates opportunities for innovation [BRA 11].

Main sources of open data:

- – public administrations;

- – private sector businesses;

- – individuals.

Figure 6.10. The inter-organizational information system must align itself with the inter-organizational territory

6.5. The job of the inter-organizational information systems planner

Urbanization of inter-organizational information systems complicates the planner’s job. The planner must in fact respond both to internal issues concerning the interoperability and urbanization of the application portfolio, and to external issues related to the stakeholder network that interacts with the company. This is not a simple extension of the perimeter, but additional capacities for interaction with new contacts in other organizations and so potentially with other strategic objectives, other business activities and other cultures. Consequently, the inter-organizational information system must align itself with the inter-organizational territory.

Figure 6.11. Summary of inter-organizational urbanization, with the representation of multiple existing information systems in the various companies and their inter-organizational relationships, the representation of multiple target information systems in various companies and their inter-organizational relationships, and the processes and skills in moving from the current to the target

The emergence of each new practice, norm or standard is likely to have implications for the urbanization project. It therefore calls for constant monitoring, together with flexibility in the organization and in the urbanization project to quickly seize emerging developments of interest to the company

Planners must network in concrete and pragmatic ways with other planners and stakeholders in information systems management in order to embrace Open Innovation-type perspectives. They must try to find room for maneuver not only in the proximity of interest with publishers, but also in a more open relationship, where room for maneuver and independence can be found. This independence is based more and more on community logics (such as user clubs and communities of practices) and alliance strategies (based on technological or strategic choices).

This increasing complexity of the urbanization project should also be balanced against the opportunities it opens up. It is in fact by being continually confronted by changes in norms and standards and proposals for improvements from stakeholders in their network that urbanization is able to promote the setting up of an agile, interoperable structure of applications and information.

Hence, in practice, the urbanization of inter-organizational information systems often has its limitations. Relationships may already be complex in a process of intra-organizational urbanization, but they become more and more so in inter-organizational urbanization. For this reason, inter-organizational urbanization is finding an effective application in a dwindling number of organizations.

6.6. Exercise: AGK

The AGK Group was born out of the recent merger of two brands of interior furniture, one French and the other Swedish, with a consolidated company turnover of 1 billion euros. The “business” strategy has three major focuses:

- – to acquire a “creative” image, follow the latest trends;

- – to be attentive, responsive and “in tune” with the end consumer (not only distributors);

- – to elevate the quality of service, both in terms of its production processes and in terms of sales support (rapid delivery, guarantees on furniture purchased, etc.).

The existing distribution model makes AGK too reliant on its distributors, both in the definition of its offers and in their presentation. The distributors mask consumers’ reactions and prevent AGK from accessing market and competitor information. Restocking times are felt to be too long for the present day. Some distributors complain that this loses more than one sale in two from customers who are interested in the catalog offers, as they are put off by the timescales quoted. These delays are attributable partly to the factories’ limited capacity, and partly to the scheduling process based on the forecasting data that is too often unreliable. Many sales are also lost due to sizes and colors not matching the living environment of interested customers.

AGK sees its operational processes evolving as follows. Distributors will no longer be treated as “resellers” (in the sense of furniture dealers), but as “exhibitors” paid commission on sales. New forms of collaboration can therefore be established, so as to optimize or even adjust the offer displayed in each location depending on context and local appeal. New methods of promotion, based on a direct relationship with AGK, will be developed for the specifiers, who are interior designers and decorators. There are no plans to open an online sales channel for consumers, as they will continue to make their purchases from local distributors.

Despite the efforts made to overhaul the information systems, finding information remains a nightmare. The introduction of an ERP has had virtually no effect, because the information is still very much structured in a layout specific to each individual’s view or understanding. It is said that you can only manage what you can measure, but at AGK, when you have measured something, you no longer have time to manage it.

The company executive intends to drive the transformation of the group in five parallel processes. The program that involves distribution aims to develop shared technical infrastructures to unify and protect the exchange infrastructures between all parties involved, both internal and external. A major business issue in this program is to open up the decision-making processes to partners through collaborative processes. Specifically, the establishment of an EDI with distributors is proposed. The growing power of the distribution chains’ information systems systematizes the use of the EDI as the quasi-exclusive mode of communication for logistics relationship and sales administration materials. Failure to comply with this constitutes a handicap that is reflected in the discount rates agreed upon. The estimated investment figure is 1.5 million euros, recoverable in two years.

Test your skills

- 1) What are the boundaries of the company’s information system?

- 2) Does EDI technology seem to you to be the best solution to meet the company’s needs and objectives?

- 3) Is the EDI aligned to the corporate strategy?

- 4) What value can be created by the EDI according to Porter’s value chain?

- 5) What alternative or complementary information systems could be considered?

- 6) What value could potentially be created by the alternative or complementary information systems you are considering?