CHAPTER 4

The Process of Strategic Thinking

Until now, we have discussed strategic thinking in a generic sense. Starting with this chapter and throughout the rest of the book, we will shift to the specifics involved with writing strategically. Before starting a strategic writing assignment, review some of the information covered in the first three chapters. Refresh your memory regarding cognitive biases, fallacies, and mental models so you avoid making any of those in your writing.

Note that writing strategically requires a good deal of preparation, time, and effort. It will take years to demonstrate a high level of proficiency. Please understand that while going into the process. When given an assignment that involves critical thinking, either at school or work, do allow yourself enough time to conduct the research, think through the process, and then write a clear, concise, and compelling memo.

The Starting Point

“The first step in fixing a problem is recognizing that one exists.” While many people claim ownership to this quote, one thing remains clear: you cannot write a strategic business paper without recognizing the problem. Doing so correctly allows you to set the stage for a clear, concise, and compelling presentation of your solution. Defining the problem incorrectly generally serves as a distraction to the reader, and often discounts any potential solutions you present in the paper.

To ensure your piece of strategic writing provides a strong starting point, follow these three steps and answer the following questions within the first paragraph or two.

Step 2. What are the causes of the problem?

Step 3. What is the extent of the problem?

Step 1: What is the problem? Clearly define the problem so the reader understands it fully. Write as if the reader is a fifth-grade student. Follow the simple rule of “if you can’t explain it to a fifth grader, you don’t understand it yourself.”

Example:

“While technology is currently providing more information and resources than ever, an overabundance of screen time is detrimental to the social and physical health of all human beings, especially children under the age of 18.”

This is the first sentence in the opening paragraph of a six-page paper. From the very beginning the reader understands the problem under review in the paper: “screen time for children under 18.” The author provides additional supporting evidence in subsequent paragraphs.

Step 2: What are the causes of the problem? Identify the causes of the problem. Articulate the causes of the problem immediately after you define the problem. Doing so provides a focus for the reader. If you abruptly state the problem without explaining the causes (step 2), or illustrating the extent of the problem (step 3), you risk losing the reader from the very beginning of your paper. Since most problems often have multiple causes, and there are constraints in space, identify just one or two causes clearly and succinctly for the reader.

Example:

“Children are becoming addicted to technological devices such as smartphones, tablets, computers and televisions from birth. Due to all the benefits regarding resources, information, and staying connected through social media, 65% of people in the United States have a smart device, or eventually gets one. Seeing their parents constantly utilizing technology creates an internal craving in children for technology. Parents tend to feed into this craving by giving children devices such as tablets and cellphones to keep them quiet or occupied, since it is the easiest way to divert a child’s attention. Parents also use technological devices as incentives for children, which only intensifies the technology addiction. What parents may not realize, however, is that they are depriving their children of opportunities to develop certain social skills that require the absence of technology use.”

Step 3: What is the extent of the problem? After you have defined the problem and its causes, the third step in the starting point requires you to illustrate the extent of it. Illustrating the extent of the problem sets up the next component of your white paper that requires you to state a goal that would result in a resolution to the problem identified.

Example:

“While the time children spend staring at screens can be controlled or monitored by parents, this excessive screen time is a consequence of constant technological advancements. According to statistics updated in May of 2017 by the Minnesota Department of Health, ‘more than 60% of children under two use screen media, and 43% watch television every day.’ The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services “estimates that American children spend a whopping seven hours a day in front of electronic media.’”

Goals

After you have clearly articulated the starting point of your strategic business writing by identifying the problem, its causes and extent, you will then need to define a goal. Like most words the term “goal” has a wide spectrum of definitions and meaning. For this exercise, and in this text, the term goal is interchangeable with objective. Goals and objectives are one in the same. Some people differentiate the two, but that often confuses the process. You outline the problem, and then you state a goal to reach in order to resolve that problem. The process remains easy, while the execution often complex.

Just as there are different types of thinking, there are different types of goals. Some of the more common types of goals are:

• Long-term and short-term goals

• Stretch goals

• SMART goals

• Big Hairy Audacious Goals (BHAGs)

Long-Term Goals and Short-Term Goals

The names of those are pretty self-explanatory. A long-term goal is something you want to do in the not so near future. Long-term goals require time and planning. They are not something you can do this week or this year. Long-term goals often require more than a year to achieve. For example, earning a four-year college degree takes, well, four years. On the other hand, a short-term goal is something you want to do in the near future. That means today, this week, this month, or by the end of this year. A short-term goal is something you want to accomplish soon. A short-term goal is a goal you can achieve in, at the most, 12 months. Earning a passing grade in this semester’s history class is a short-term goal.

Stretch Goals

Stretch goals inspire us to think big and remind us to focus on the big picture. They require extending oneself to the limit to be realized. They represent a challenge that is significantly beyond the individual’s current performance level. Stretch goals energize and push you to work more intelligently and harder at meeting what seems to be more difficult targets and to accomplish more than if you had set an easier goal. When you set a stretch goal for yourself, you know that you may not meet it 100 percent, but by moving in this direction you will likely achieve extraordinary results.

SMART Goals

The acronym SMART stands for goals that are Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Realistic, and Time-bound. They help us form a plan of actions in translate a goal into reality. SMART goal setting brings clarity, structure, and trackability to your goals.

• Specific—exactly what it is that you want to achieve.

• Measurable—you must be able to track progress and measure the result of your goal.

• Achievable—you should see the way to achieve your goal by taking certain steps.

• Realistic—the goal should be realistic and relevant to your stretch goal. Make sure the actions you need to take to achieve your goal are things within your control.

• Time-bound—your goal must have a deadline.

BHAGs

BHAG stands for Big Hairy Audacious Goal, an idea conceptualized in the book, Built to Last: Successful Habits of Visionary Companies by James Collins and Jerry Porras. According to Collins and Porras, a BHAG is a long-term goal that changes the very nature of a business’s existence.

BHAGs are meant to change how we do business, the way we are perceived in the industry, and possibly even the industry itself. Collins and Porras describe BHAGs on a corporate level as nearly impossible to achieve without consistently working outside a comfort zone and displaying corporate commitment, confidence, and even a bit of arrogance.

A BHAG is usually a 10+ year forward-looking goal that describes your future. It should stretch you and guide you, while helping you determine what to say yes and no to, as you progress to accomplish your goals. A BHAG can also be a personal vision statement. Where do you see yourself in 5 or 10 years? What are some bold or daring things you’d like to accomplish?

Three BHAG examples:

• Microsoft: A computer on every desk and in every home.

• SpaceX: Enable human exploration and settlement of Mars.

• Google: Organize the world’s information and make it universally accessible and useful.

Strategies

Your strategy, detailed in the white paper, must clearly explain a plan of action to achieve the specific goal you described. To create viable strategies from which to choose, use the following three-step process:

Step 1: Brainstorm

Step 2: Prioritize

Step 3: Decide

Let’s say you need to identify a new coffee supplier at your office. Much bigger problems exist in the world, but your boss gave you this task. Even a task as small as this can benefit from strategic thinking.

Step 1: Brainstorming might result in the following strategies as potential options:

1. Purchase a “Bean to Cup” machine.

2. Purchase a machine that uses k-cups.

3. Have an employee go to a store each morning to pick up everyone’s order.

4. Hire someone go to a store each morning to pick up everyone’s order.

5. Ask people to bring in their own coffee.

6. Hire a coffee supplier to set up a cart in the office building.

For assistance on learning how to develop brainstorming ideas, see the chapter entitled “Red Ocean v. Blue Ocean.”

Step 2: Prioritize the results of your brainstorming based on a specific criterion. For this example, we will use cost as the criterion that allows us to prioritize the six options.

1. Ask people to bring in their own coffee (no cost to company).

2. Have an employee go to a store each morning to pick up everyone’s order (indirect cost to company in lost productive work time for pick-up employee).

3. Purchase a machine that uses k-cups (~$200 up front and $100 monthly).

4. Purchase a “Bean to Cup” machine (~$900 up front and $400 monthly).

5. Hire someone go to a store each morning to pick up everyone’s order (~$800 monthly).

6. Hire a coffee supplier to set up a cart in the office building (~$1,200 monthly).

Step 3: Deciding on a specific strategy does not necessarily mean that you select the item at the top of your priority list. For this example, the company CEO passes on the first two strategies (1. ask people to bring in their own coffee or 2. have an employee go to a store each morning to pick up everyone’s order). The CEO believes in treating her people to free coffee and purchasing a new machine that uses k-cups remains the most affordable option for her among the remaining four options. To help with the selection process, many people will review the tactics involved with each strategy. The next section will explain tactics and their relationship to strategies.

Understanding the decision-making process will serve as a useful tool when people read your white paper and ask you how you determined your strategy. A mature strategic thinker and writer will incorporate the other strategies considered in any conversation about the white paper. Intelligently discussing how you selected a strategy among many ideas remains one of the reasons why writing a clear, concise, and compelling white paper takes time to develop, several draft attempts, and substantial editing.

Tactics

During the decision-making process of selecting a strategy, tactics are often included as part of the evaluation process. The easiest way to remember the difference between strategies and tactics is that: strategies help you achieve the goal, while tactics allow you to implement the strategies. This process provides you with an efficient and effective means of thinking and writing strategically. Let’s take a look at one example.

One strategy under consideration, and ultimately selected, was: “Purchase a machine that uses k-cups (~$200 up front and $100 monthly)” To fully understand this strategy you will need to list all of the tactics involved with implementation. NOTE: When you are deciding on a strategy, it is very important not to dismiss a strategy as you are thinking about all of the tactics involved. It is at this point in the process that some people will dismiss a strategy as quickly as it is placed on the table as an idea because they are thinking of all of the work involved. As noted earlier in the strategies section, remain open to considering all strategies, and their tactics, prior to making a decision. How quickly you make a decision is a critical component of your decision-making process. Here are eight of the tactics involved with the strategy “Purchase a machine that uses k-cups (~$200 up front and $100 monthly)”:

1. Research the different machines.

2. Identify a location for the machine.

3. Determine which k-cups to order.

4. Define the inventory of k-cups required.

5. Create a schedule of ordering new k-cups.

6. Decide who will oversee the machine and supplies.

7. Figure out what department/s will pay for the machine and supplies.

8. Locate a supplier for the machine and supplies.

Some strategic thinkers will detail all the tactics involved with each proposed strategy prior to making a decision. Over time you will figure out the best way for you to think strategically, but this guide can help you get started.

Strategies and Tactics in Business

To better understand the application of strategies and tactics, let’s examine the IBM 2018 Survey of C-Suite Executives. The majority of C-suite executives will proclaim that survival today requires constant reinvention. As noted in the survey report, “Remaking the enterprise is not a matter of timing but of continuity. What’s required, now more than ever, is the fortitude for perpetual reinvention. It’s a matter of seeking and championing change even when the status quo happens to be working well. As new opportunities—some of them disruptive—emerge, the organizations that remain open to change can orchestrate advantage.”1 The following series of strategies and related tactics included in the IBM report offer executives a few options to consider, as they look for ways to reinvent their organizations.

1. Strategy #1: Interrogate your environment

a. Tactic #1: Remain on high-alert and avoid complacency about past successes: Actively scan the business landscape for disruptive change coming from industry incumbents, including those in adjacent industries.

b. Tactic #2: Design and play a new offense: Boldly evaluate, experiment, and engage with new business models, industry-shaping platforms, and ecosystem strategies that you could adopt to significant advantage.

c. Tactic #3: Get even closer: Create opportunities for frequent and intense interactions with customers, partners, and competitors. Test existing assumptions and drive totally new strategies.

2. Strategy #2: Commit with frequency

a. Tactic #1: Divest to invest: Act quickly against the possibility of disruption by adopting a fluid capital reallocation mind-set. Frequent capital reallocation from low to high potential opportunities should be an agile exercise.

b. Tactic #2: Invest for new growth: Create market-shaping and capability-building investments that inject innovation, new talent, and technologies into your enterprise.

c. Tactic #3: Prioritize advocacy and co-creation over advertising: Maximize investments that build customer trust and brand value.

3. Strategy #3: Experiment deliberately

a. Tactic #1: Seek innovation over institutionalization: Don’t solidify a competitive advantage; it’s likely fleeting. Expect it to be transitory and start working on the next audacious opportunity.

b. Tactic #2: Write new rules: To create a more open and collaborative culture, look for ways to challenge traditional norms.

c. Tactic #3: Find energy in motion: Create new motion through continuous innovation, but don’t dismiss the potential to benefit from others’ ideas. Find opportunities to co-create with customers, partners, and even competitors.

For the complete IBM report visit https://www.ibm.com/services/insights/c-suite-study

The Strategic Planning Outline Template (SPOT)

The adjacent image is called a Strategic Planning Outline Template (SPOT). SPOT provides you an opportunity to create a simple overview for your six-page paper. Presenting a clear, concise, and compelling piece of strategic business writing demands that you design a strong strategic planning outline. Use this template for every piece of strategic business thinking, planning, or writing. Photocopy this page or simply diagram this outline on a blank sheet of paper. SPOT consists of four separate, yet equally important, elements. This chapter explains each of the following four elements in greater detail.

• Current situation/problem: this box in the upper left-hand corner allows you to identify your topic.

• Goal: the Specific, Measurable, Actionable, Realistic, and Timely (SMART) goal you have in mind.

• Strategy: the strategic imperative that you will use to accomplish your goal. If you want to, you should consider listing the other strategies you thought about using on the right of the strategy box.

• Tactics: the steps required to help you accomplish your strategy. In a six-page memo three tactics would suffice. There is no steadfast rule here so the number of tactics discussed will be up to you. As a rule of thumb, two would be a minimum and four would be a maximum.

This SPOT will help you see your strategic thinking in a very clear fashion. Once outlined, review your SPOT with someone and see if that person can follow your logic where you identify a problem, set a goal to resolve that problem, create a strategy to implement to achieve your goal, and then develop a series of tactics to help you implement the strategy. For more information on each of the four elements of SPOT, review this chapter.

Understanding Blue v. Red Ocean Strategies

Blue Ocean Strategy is a marketing theory from a 2005 book entitled Blue Ocean Strategy: How to Create Uncontested Market Space and Make the Competition Irrelevant by W. Chan Kim and Renée Mauborgne, professors and codirectors of the INSEAD Blue Ocean Strategy Institute. Based on a study of 150 strategic moves spanning more than a hundred years and 30 industries, Kim and Mauborgne argue that companies can succeed by creating “blue oceans” of uncontested market space, as opposed to “red oceans” where competitors fight for dominance, the analogy being that an ocean full of vicious competition turns red with blood.

They assert that these strategic moves create a leap in value for the company, its buyers, and its employees, while unlocking new demand and making the competition irrelevant. The book presents analytical frameworks and tools to foster an organization’s ability to systematically create and capture blue oceans. An updated edition of Blue Ocean Strategy was published in February, 2015.

Kim and Mauborgne argue that while traditional competition-based strategies (red ocean strategies) are necessary, they are not sufficient to sustain high performance. Companies need to go beyond competing with each other. To seize new profit and growth opportunities, they also need to create blue oceans. The authors argue that competition-based strategies assume that an industry’s structural conditions are given and that firms are forced to compete within them, an assumption based on what academics call the structuralist view, or environmental determinism. To sustain themselves in the marketplace, practitioners of red ocean strategy focus on building advantages over the competition, usually by assessing what competitors do and striving to do it better. Here, grabbing a bigger share of the market is seen as a zero-sum game in which one company’s gain is achieved at another company’s loss. Hence, competition, the supply side of the equation, becomes the defining variable of strategy. Here, cost and value are seen as trade-offs, and a firm chooses a distinctive cost or differentiation position. Because the total profit level of the industry is also determined by structural factors, firms principally seek to capture and redistribute wealth instead of creating wealth. They focus on dividing up the red ocean, where growth is increasingly limited.

Blue ocean strategy, on the other hand, is based on the view that market boundaries and industry structure are not fixed and can be reconstructed by the actions and beliefs of industry players. This is what the authors call the reconstructionist view. Assuming that structure and market boundaries exist only in managers’ minds, practitioners who hold this view do not let existing market structures limit their thinking. For them, extra demand is out there, largely untapped. The crux of the problem is how to create it. This, in turn, requires a shift of attention from supply to demand, from a focus on competing to a focus on value innovation—that is, the creation of innovative value to unlock new demand. This is achieved via the simultaneous pursuit of differentiation and low cost. As market structure is changed by breaking the value/cost trade-off, so are the rules of the game. Competition as in the old game is therefore rendered irrelevant. By expanding the demand side of the economy, new wealth is created. Such a strategy therefore allows firms to largely play a non-zero-sum game, with high payoff possibilities.

Starbucks remains of the most successful organizations to employ a blue ocean strategy: Starbucks entered a historically crowded marketplace, the coffee shop industry. However, it found its way to success through the blue ocean strategy. Starbucks separated itself from the competition by combining differentiation, low cost, and a customer-oriented approach from the beginning of its operation. Starbucks also focused on maximizing its brand’s exposure, rather than in solely focusing on itself as just another coffee shop. In terms of differentiation, Starbucks offered a variety of products, such as smoothies, teas, and coffees that no other establishment was offering. By training specialized staff, the company operated with less staff than would usually be needed. Starbucks also championed professionalism and excellent customer service, for example, offering personalized coffee cups. To enhance the customer experience, Starbucks changed the furnishings in their stores, creating a comfortable environment that persuades their customers to spend more time in store.

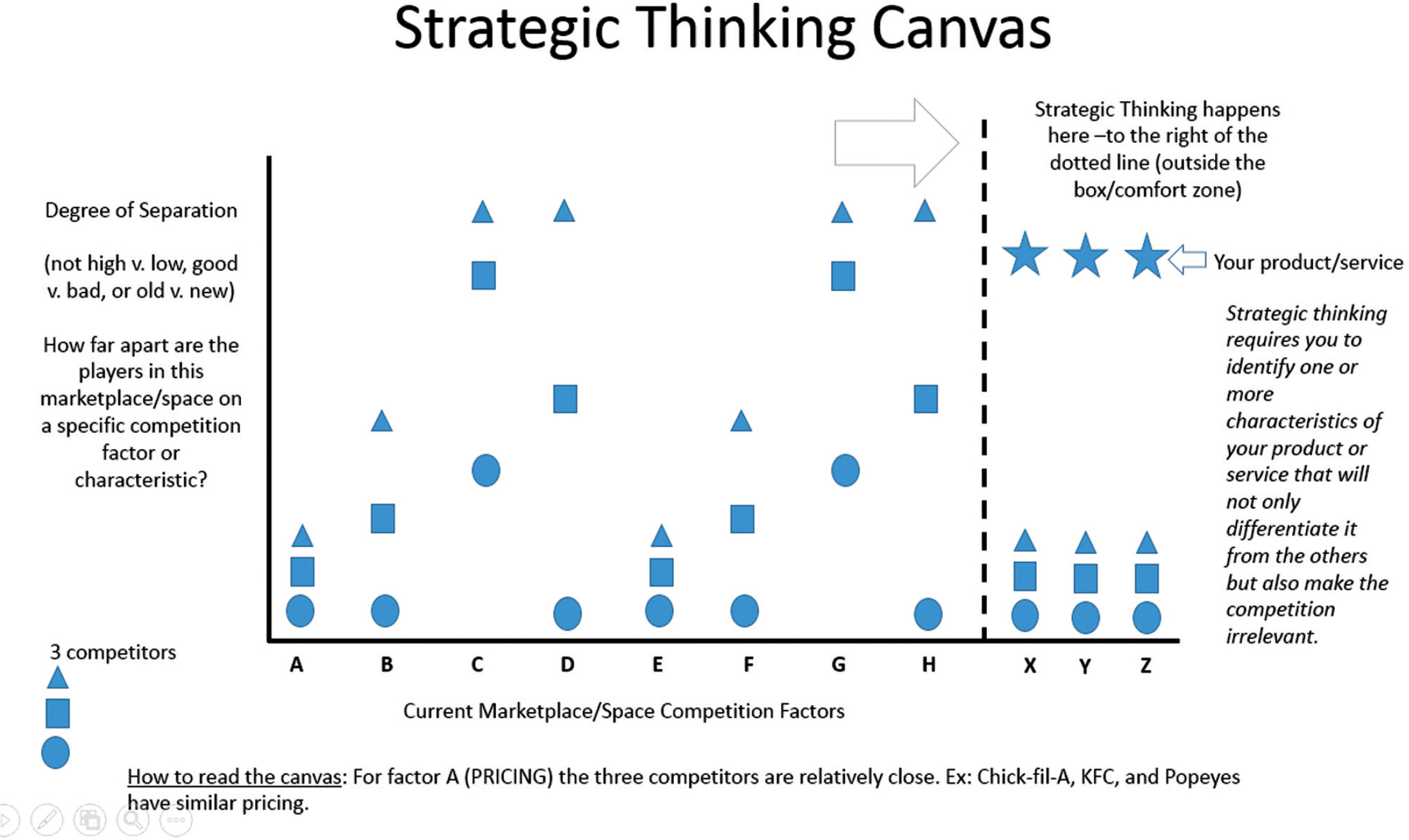

Strategy Canvas

Strategic thinkers and writers use a variety of tools to help them craft clear, concise, and compelling stories. The strategy canvas that represents a visual representation of the current market is one such tool. Arriving at an original thought remains the cornerstone of strategic thinking. To do that, however, one needs to scan the current situation, identify how the current market is similar, and then suggest a new idea to implement. To identify a blue ocean strategy that makes the competition irrelevant, here are the steps involved with creating a strategy canvas. You should try to create a strategy canvas for any of the six-page memos you write.

• Step 1: Define the marketplace you need to assess. (e.g., fast-food restaurants that focus on chicken).

• Step 2: Identify at least three of the current players in the marketplace. (e.g., Chick-fil-A, KFC, and Popeyes).

• Step 2: Select a shape to represent each player (e.g., a circle represents Company A, a triangle represents Company B, and so on).

• Step 3: List the dynamics currently driving the marketplace. (e.g., pricing is often a very common dynamic driving the fast-food marketplace).

• Step 4: Place the shape related to each player in relation to how close or far it is to the other players. In the adjacent strategic canvas provided here the topic is fast-food restaurants that focus on chicken only. You will see that the three shapes represent Chick-fil-A, KFC, and Popeyes. Since they each have similar pricing, all three shapes are close together on the canvas. NOTE: The canvas does not use a high or low ranking. The objective is to have a visualization of the relationship between the players and the current dynamics driving the market. Identify at least five or more dynamics for your canvas.

• Step 5: On the right side of the canvas, draw a vertical line. This is where strategic thinking is involved. Identify that one dynamic that will help you create a blue ocean strategy and make the competition irrelevant. See the next page for an example of a strategy canvas.

A Profile in Strategy #4: The Blue Ocean Strategy of Starbucks

After operating Starbucks for 15 years, the original owners sold the small coffee shop with just six stores to former manager Howard Schultz with a vision to expand across the globe. It was during this time that Howard Schultz went searching for investors who believed in his vision. Of the 242 investors Schultz talked with, 217 rejected him. In Life Entrepreneurs, Christopher Gergen and Gregg Vanourek wrote about the time when Schultz’s father-in-law visited him during this 200 plus rejections. As Schultz recalls, “He asked me to go for a walk. I knew what was coming. We sat down on a park bench. As God is my witness this is exactly what happened. He says: ‘I don’t want to be disrespectful but I want you to see the picture I’m looking at. My daughter is seven months pregnant and her husband doesn’t have a job, just a hobby. I want to ask you in a heartfelt way, with real respect, to get a job.’ I started to cry, I was so embarrassed. We went back to the house and I really believed it was going to be over. That night in the privacy of our bedroom, I told my wife the story. I was so disappointed. Not angry, disappointed. She was the one that said: ‘No, we’re going to do it. We’ll raise the money.’ If she’d said: ‘He’s right,’ it would have been over. I’m sure of it.”2 With a tremendous belief in his vision and a relentless amount of perseverance, Schultz convinced enough investors to give him the money he needed and soon Starbucks opened its first locations outside Seattle at Waterfront Station in Vancouver, British Columbia, and Chicago, Illinois. By 1989 Schultz had opened 46 stores across the Northwest and Midwest. Today there are over 20,000 Starbucks locations around the globe. As Schultz observed, “I believe life is a series of near misses. A lot of what we ascribe to luck is not luck at all. It’s seizing the day and accepting responsibility for your future. It’s seeing what other people don’t see and pursuing that vision.” Schultz launched Starbucks as an international brand by using the blue ocean strategy and positioning his coffee shop as the “third place,” where people could go to besides home and work. Doing so revolutionized our way of living, working, and interacting with others.

Thinking Exercise #4: How Good Do You Want to Be?

All you have to do is answer one question: “So how good do you want to be?” Only you can answer this question. Take your time. Do some research and figure out if you want to be quite good, the best in the world, or somewhere in between. Why did you answer the way you did?

1IBM, C-Suite Study, 2018. Visit https://www.ibm.com/services/insights/c-suite-study for report.

2Christopher Gergen and Gregg Vanourek, Life Entrepreneurs: Ordinary People Creating Extraordinary Lives, Jossey-Bass, New York, 2008.